1. Introduction

Horticulture and forestry are major reasons for the introduction of exotic trees (Richardson & Rejmanek, 2011). However, alien species may have negative ecological impacts (Vilà et al., 2011), and forests are not spared (Holmes et al., 2009). This situation may result in a conflict of interest between foresters and environmental managers (Dickie et al., 2014).

Effective propagule dispersal is essential for an introduced species to progress from naturalization to invasion (Richardson & Rejmanek, 2011). In the case of animal-dispersed trees, disperser communities are likely to differ between the native and introduced ranges. A better understanding of seed dispersal in the introduced range is required to confirm the invasive potential of an alien tree species.

Native to North America, the northern red oak (Quercus rubra L.) was declared as invasive in several European countries (e.g. Woziwoda et al., 2014) and was shown to induce negative ecological impacts (e.g. Riepšas & Straigyte, 2008). In its native range, it is dispersed by birds and rodents (Sork et al., 1983; Gribko et al., 2002). Scatter-hoarding rodents, through burying acorns and covering them with litter, act as significant dispersers and create favorable conditions for germination (García et al., 2002). In Europe, acorns of native oaks are consumed by animal species, some of which play a significant role in dispersal: birds, particularly the European jay (Garrulus glandarius L.), and scatter-hoarding rodents, especially wood mice (Apodemus sylvaticus L.) (Ouden et al., 2005). While the European jay plays a role in the dispersal of Q. rubra acorns above the ground (Myczko et al., 2014), little is known about the removal of Q. rubra acorns fallen on the ground in its introduced range (but see Bieberich et al., 2016). In our study, we asked:

– are acorns of Q. rubra moved away by animals on the ground?

– which animals are involved and among them, which can be considered scatter-hoarders?

– are acorns of Q. rubra and Quercus robur L. removed at the same rate?

2. Materials and methods

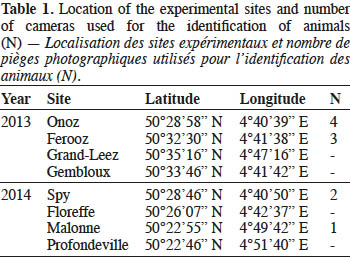

In autumn 2013 and 2014, four experimental sites (> 3 km apart) were selected in southern Belgium (Table 1). All sites were mixed oak stands dominated by adult trees of Q. robur and/or Q. rubra. Acorns of both species were collected from the ground under fruiting trees and stored at room temperature. Acorns with obvious damages were discarded. Acorns were manipulated with latex.

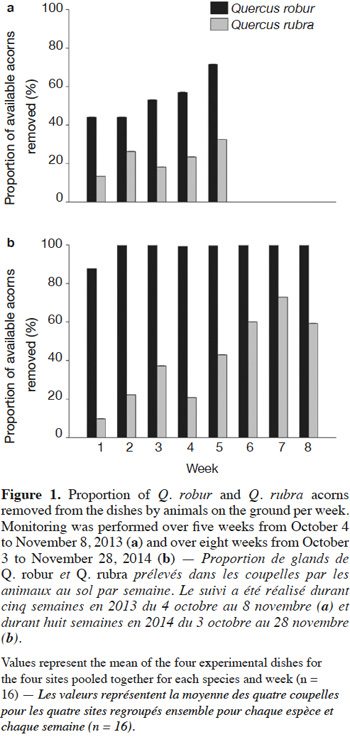

At every site, four pairs of 28-cm diameter plastic dishes (10-20 cm apart) were randomly placed on the ground. One dish per pair contained 20 acorns of Q. robur, the other 20 acorns of Q. rubra. Every week, the acorns remaining in each dish were counted and removed, and the dishes were refilled with 20 acorns. When a dish was accidentally spilled, the data of the considered week were ignored. The experiment lasted from 04/10/2013 to 08/11/2013 and from 03/10/2014 to 28/11/2014. Automated detection cameras (Cuddeback Digital, USA) were attached 30-50 cm high on the nearest trunk and pointed at the dishes. When movement was detected, the cameras took pictures every 5 seconds and recorded a video for 10 seconds. Seven and three cameras were available in 2013 and 2014, respectively, and were positioned in two sites (Table 1). Identification of recorded animals was made using mammal guide books (Quéré & Le Louarn, 2011; Aulagnier et al., 2013). The videos allowed distinguishing acts of consumption from acts of collecting and scattering. We then classified the observed animals as pure consumers or scatter-hoarders of Q. rubra acorns, in agreement with the scientific literature regarding their feeding behavior.

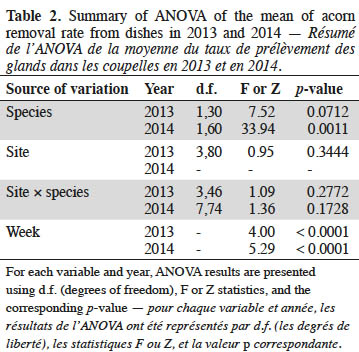

For each Quercus species, the number of acorns removed from the dishes was converted to the proportion of acorns removed during one week, i.e. acorn removal rate. For each site, the mean acorn removal rate of the four dishes was calculated according to species and week, and arcsine-transformed. A mixed model with repeated measurements (proc. MIXED) was used to analyze the effects of species (fixed), week (random), site (random), and the interaction site × species on the mean acorn removal rate. Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., USA).

3. Results

Acorns from both species were removed on the ground by animals during all considered weeks at all sites. Acorn removal rate did not differ between species in 2013. In 2014, acorns of Q. robur were preferred to acorns of Q. rubra. In both years, the acorn removal rate for Q. rubra increased from the beginning to the end of the monitoring (Table 2, Figure 1). Effects of site and interaction site × species were not significant (Table 2).

Based on camera traps, we identified four mammal species removing Q. rubra acorns. Wood mice (A. sylvaticus L.; 2013: 14 records; 2014: 0 record) and red squirrels (Sciurus vulgaris L.; 2013: 18 records; 2014: 0 record) were identified as consumers and scatter-hoarders. The pictures and videos distinctly showed them removing Q. rubra from the dishes (http://hdl.handle.net/2268/209505). Wild boars (Sus scrofa L.; 2013: 0 record; 2014: 4 records) and rats (Rattus sp.; 2013: 0 record; 2014: 7 records) were regarded as pure consumers of Q. rubra acorns because they were only seen eating acorns in the dishes, which was in concordance with the literature. No bird species were observed.

4. Discussion

We demonstrated that mammals removed acorns of Q. rubra on the ground in Belgian forests. Wild boars and rats consume acorns but do not efficiently act as dispersers (Schley & Roper, 2003; Quéré & Le Louarn, 2011). In contrast, the scatter-hoarding rodents observed in our study, i.e., wood mice and red squirrels, are known for caching and burying native acorns (Wauters & Casale, 1996; Ouden et al., 2005) and can therefore be considered as potential dispersers of Q. rubra. Considering both years, scatter-hoarders were recorded three times more frequently than pure consumers.

Across the two years, the acorn removal rate was higher for Q. robur than for Q. rubra. This can be attributed to the habits of the animals, as well as intrinsic properties of acorns. Quercus rubra acorns contain more fat than Q. robur acorns but have higher levels of tannins, known as chemical defenses that induce a bitter and astringent taste (Shimada & Saitoh, 2006). In the native range, high tannin levels render Q. rubra acorns less palatable than other oak species and protect the embryos from consumption and subsequent damage (Steele et al., 1993).

Major et al. (2013) suggested that the dense regeneration of seedlings beneath red oak trees was related to the absence of seed movement on the ground. Our results indicate that a significant proportion of Q. rubra acorns, even if not preferred over native acorns, may be dispersed on the ground by scatter-hoarding rodents. Generally, scatter-hoarding rodents disperse intact or partially eaten acorns over areas approximately ranging from 100 m2 (wood mice) to 15 ha (squirrels) (Perea et al., 2011; Quéré & Le Louarn, 2011). Potential dispersal distances can thus vary from a few meters to hundreds of meters according to the species and number of repeated dispersal actions (Perea et al., 2011).

5. Conclusions

Scatter-hoarding animals, though they do not seem to prefer northern red oak acorns over native oak acorns in Western Europe, may help the species increasingly colonize forest ecosystems through acorn movement on the ground.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Thierry Kervyn for access to Onoz site and Alain Licoppe for the loan of camera equipment. This study has been carried out with financial support from the French National Research Agency (ANR) in the frame of the Investments for the future Program (ANR-10- IDEX-03-02); and from the University of Liege in the frame of the “Fonds spéciaux pour la recherche”.