- Accueil

- Volume 43 (2025)

- Mines’ vulnerabilities in Mabayi Commune (Burundi)

Visualisation(s): 292 (11 ULiège)

Téléchargement(s): 0 (0 ULiège)

Mines’ vulnerabilities in Mabayi Commune (Burundi)

Résumé

L'exploitation minière crée de nouvelles activités, des emplois et des revenus pour les communautés locales. Elle peut également renforcer les facteurs externes négatifs, réduisant la production agricole et rendant les petits exploitants vulnérables, si elle n'est pas correctement gérée. Cet article vise à analyser les facteurs de vulnérabilité, le rôle des activités minières sur les actifs des ménages ruraux en présence de ces facteurs, et partant sur leur production agricole. Une enquête auprès de 210 ménages, des entretiens avec des informateurs clés et des observations ont été réalisés en 2022 dans la commune de Mabayi sur les collines Gahoma et Ruhororo, où la société minière étrangère "Tanganyika Mining Burundi-TMB" et la coopérative minière locale "Dukorere Hamwe Dusoze Ikivi-DHDI" menaient respectivement leurs activités d’exploitation d’or depuis décembre 2018. En comparant les campagnes agricoles 2017-2018 et 2020-2021, les résultats montrent que la colline de référence a connu une diminution de production agricole moyenne de 153 kg/ménage/an due aux facteurs négatifs externes aux mines dont ceux habituels de vulnérabilité. La colline Gahoma a connu une réduction de 826 kg/ménage/an suite aux facteurs négatifs externes dont ceux habituels de vulnérabilité, et aux activités minières de TMB. La colline Ruhororo a connu une réduction de 136 kg/ménage/an suite aux facteurs négatifs externes dont ceux habituels de vulnérabilité. Une gouvernance inclusive et/ou participative de toutes les parties prenantes devrait contribuer à un développement socio-économique plus viable et durable.

Abstract

Mining creates new activities, jobs and income for local communities. It can also reinforce negative external factors, reducing agricultural production and making the smallholders vulnerable, if not properly managed. This paper aims to analyze vulnerability factors, the role of mining activities on the assets of rural households in the presence of these factors and on their agricultural production. A survey of 210 households, interviews with key informants, and observations were carried out in 2022 in Mabayi’s commune on Gahoma and Ruhororo hills, where foreign mining company ‘‘Tanganyika Mining Burundi-TMB’’ and local mining cooperative “Dukorere Hamwe Dusoze Ikivi-DHDI” had been respectively operating gold since December 2018. Comparing the 2017-2018 and 2020-2021 agricultural seasons, the results showed that the Buhoro reference hill experienced a decrease in average agricultural production of 153 kg/household/year due to negative factors external to the mines including the usual ones of vulnerability. On the Gahoma hill, it was reduced by 826 kg/household/year as a result of these factors and the mining activities of the TMB Company. On the Ruhororo hill, it fell by 136 kg/household/year due to negative external factors, including the usual vulnerability factors. Inclusive and/or participative governance of all stakeholders should contribute to more viable and sustainable socio-economic development.

Table des matières

Introduction

1African countries are increasingly turning to mining as a potential internal resource for their economies (OECD, 2016). A significant proportion of foreign direct investment is directed towards the extractive industries sector (Ibid., 2016). Nowadays, mining is second to agriculture in the economies of these countries (Musokotware, 2016). Yet the effects of mining are manifold (i.e social and economic), affecting political leaders, local communities (especially those living in the vicinity of extraction sites), the environment, health, etc. (Ibid., 2016), though mines stimulate growth in the countries that own and value them, through their positive effects on Gross Domestic Product (GDP) (WB, 2015). Mining enables an improvement and increase in agricultural activity among certain households notably the wages of the jobs created and the mining industries community development programs (Adjei, 2007). Mining sites offer a remunerative consumption market for agricultural products, a shorter cycle for their purchase and a strong attraction for traders (Zabsonré et al., 2016).

2Despite these positive effects of mining, negative effects are mentioned. Direct negative effects are a reduction in the time devoted to agricultural activities, as farmers consider mining labor to be more lucrative than farming. They drop certain crops for fear of untimely land claims by mining companies (Ibid., 2016). Active agricultural labor is captured by the mines resulting in the loss of family agricultural labor (mainly young people) no longer under the control of family heads and the scarcity of land makes it more expensive to purchase or rent. Other effects include the resettlement or uprooting of land leading to the destruction of plantations, the depletion of arable land by residential agglomerations around mining sites, the destruction of soil structure, high input prices (Ibid., 2016) and the decline in agricultural production due to environmental pollution, particularly groundwater pollution (Adjei, 2007; Musokotware, 2016).

3To boost the country's economy, the Burundian government has, since 2005, diversified its sources of revenue by developing various potential sectors, including mining (Vircoulon, 2019). In Burundi, mining extraction began in 2014.The country holds 6% of the world's nickel reserves, as well as reserves of gold, tantalum, tin, tungsten, vanadium, rare minerals, construction materials and industrial materials including kaolin, phosphates and limestone. (AAIB, 2019). Mining resources are the second-largest source of export revenue after coffee and employ (particularly mining cooperatives) a national workforce estimated at nearly twenty-five thousand (Vircoulon, 2019). Although their share of state financing is still insignificant (1% in GDP, 3% in export earnings and 1.71% in the general budget), it stimulates the country's growth (Alhasan, 2014; WB, 2015; Mokam and Tsikam, 2017; AAIB, 2019). Despite this contribution to GDP growth and job creation, the socio-economic development of farming households in the vicinity of mining sites in the study area is being called into question. Indeed, GDP growth is not converted into compensation for these households' losses, nor into poverty reduction in rural areas. Nsabimana (2019) qualifies mining activities as causes and amplifiers of soil erosion in this area. The existence of negative factors external to these activities makes agricultural production vulnerable. The purpose of this paper is to provide an analysis of the habitual vulnerability factors, the role of mining activities on the assets of rural households in the presence of these factors, and hence on their agricultural production on the Gahoma and Ruhororo hills of Mabayi commune, where the Russian company TMB and the local cooperative DHDI have been conducting their activities since December 2018, respectively.

Materials and methods

Description and choice of study area

4The study was carried out in the Mabayi commune. This is an agricultural area where bananas are the main crop. Other crops grown by the majority of the population include maize, beans, cassava, sweet potatoes, potatoes and colocases. Rice, coffee, tea, wheat, tomatoes, pineapples, etc. are also grown by some households. Livestock farming generally involves small livestock due to the very rugged landscape (MAE, 2016). Animals raised include goats, pigs, sheep, rabbits, chickens, etc. (Ibid., 2016). Small businesses, selling a variety of products and services are also practiced. The other activity practiced is informal gold mining, trough which some miners still exploit the richness of the land (AAIB, 2019; Nsabimana, 2019; Vircoulon, 2019).

5The commune has a very abrupt relief, with altitude varying between 1,500 and 2,652 m (Nsabimana, 2019). It has abundant rainfall, often reaching 200 mm per month (Ibid., 2019). These natural features of the area make the land vulnerable to erosion, and thus more vulnerable to the environmental effects of mining activities. Added to these characteristics, the commune has the high population density -between 500 and 650 inhabitants/km2 according to the location (MAE, 2016) - making access to land more difficult in this commune compared to other mining areas. Furthermore, with a population of approximately 103,623 (INSB, 2020) and a total area of 347.54 km2 (Nsabimana, 2019), the population density shows that around half of this commune area is not potentially arable. These factors increase the vulnerability of the agricultural sector to the effects of mining activities. Hence the motivation to choose this commune as our study area.

Sample selection

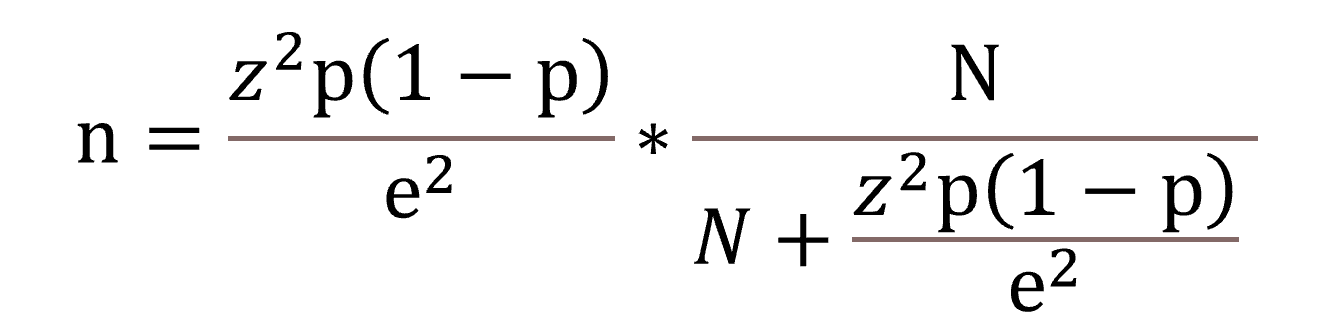

6The Gahoma and Ruhororo hills have an average of 800 households each, giving an average total of 1,600 households. The sample size was determined using the simple random sampling formula (Yoann, 2021):

With N = the source population (households) or 1600 households; z = 1.96 for a confidence level of 95%; e = margin of error of 5%; p = proportion of the characteristic of interest (to be chosen or not) in the population - households, set at 0.50.

7Using this formula, the sample size n becomes roughly equal to 309 households for the two hills. Statistically, a sample of fewer than 30 respondents is worthless, but once there are 30 or more, all is well (Bouchard, 2011). Thus, taking into account the practically similar characteristics of the households and their very close location, but also and above all the budget and time constraints, we opted to take into account almost half of the sample, i.e. 140 households for the two hills, and 70 households per hill. We also added 70 households for the Buhoro reference hill, making a total of 210 households. Apart from the mining activities that take place on Gahoma and Ruhororo hills, with their related effects; all other features (geographical and socio-economic) developed in the previous point are identical to those of Buhoro hill. The three hills also have the same organizational feature - rural social organization dominated by kinship (Todd, 1999), and had approximately the same quantity of agricultural production before advent of mining activities. Hence Buhoro hill, located about 31.9 km and 29.7 km from Gahoma and Ruhororo hills respectively, was taken as a reference. It was then necessary to include 35 households who had lost all or part of their agricultural land, along with 35 other households who had not lost any land, in order to assess the impact of mining activities on the agricultural production of both categories of household. However, as only 17 households in Ruhororo hill had lost land, we included them all in the sample, along with 53 other households who had not lost land. These households were selected using the interval 4 random sampling method, from lists of households (a list of households that have not lost land, and a list of households that have lost land) provided by the hill chiefs.

Data collection

8This paper is based on primary and secondary data. Primary data were collected in July and August 2022. We used a questionnaire, three interview guides, and observations. Two interview guides were individual: one for opinion leaders and another for the communal agronomist, public and community relations officers at TMB company and DHDI cooperative. The third interview guide was used for group interviews and focus groups. With the help of three local interviewers, the questionnaire was sent to the heads of 210 households in their homes (70 households per hill for the two mining hills Gahoma and Ruhororo, and 70 households for the non-mining hill Buhoro). With this sample, we collected quantitative data on agricultural production before and during mining activities (2017-2018 season and 2020-2021 season). For the Gahoma hill, among the 70 households, 35 households had lost land (out of a total of 80 households that had lost land on the entire hill) and other 35 households had not. As for Ruhororo hill, of the 70 households, only 17 households had lost land (out of a total of 17 households that had lost land on the whole hill), and 53 households had not.

9Individual interviews were conducted with opinion leaders (2-one man and one woman/hill), the communal agronomist, and public and community relations officers. Group interviews consisted of gathering and interviewing people with different profiles and interests. With a minimum of six people, they were conducted with miners (for mining hills), students and other household members. The latter were members other than the heads of households, but known by the head of the hill as possessing important information about changes since the advent of the mining company/cooperative's activities or since December 2018. Focus groups consisted of gathering and interviewing people with the same profile, and with the same interest. Also with a minimum of six people, they were conducted with students. These informants were chosen teleologically because they were known in advance to possess important information about the changes that had taken place. A meeting was held with these informants during the exploratory phase, in the presence of the hill leaders, to facilitate understanding of the research interest and maximize the validity (and reliability) of the interviews. Students who were interviewed (in group interviews and focus groups) were natives of considered hills, and were in upper secondary school in local colleges. They were chosen alone in the focus groups for two reasons: they are among intellectuals with more advanced capacity for analysis than simple peasant farmers, and are only ones who could be available on site in an interesting number among other categories of intellectuals native of study area.

10In the questionnaire and interview guides, questions were based on five variables corresponding to the five basic capitals for rural household livelihoods: natural capital, human capital, physical capital, financial capital, and social capital. The questions related in particular to the size of farms before and during mining activities, the quantity of agricultural production per season and per crop before and during mining activities, the income from farms per season and per crop before and during mining activities, the purchase/rental or other price of land before and during mining activities, the number of household members by level of education, the number of household members who worked in the mines, the remuneration of the manual agricultural worker before and during mining activities, capacity building in agriculture, non-farm income sources of households, etc. The quantities produced were measured in kilograms (kg) using local units of measurement. These quantities were then multiplied by the local unit prices for each product. Possible semi-structured questions in the interview guides focused on the causes of the changes since the advent of the mining company/cooperative (or since December 2018), the general perception of their effects on farm production and income, and hence on the livelihoods of farm households. Products grown by the majority of households in Mabayi (maize, beans, bananas, cassava, sweet potatoes, potatoes and colocase) were taken into account. All survey participants were aged 18 or over, and had to have lived in the communities since before 2018, with the exception of the communal agronomist and the public and community relations officers.

11Secondary data were collected through papers, books and other documents relating to our topic. For data relating to agricultural production, the country has a single recognized national institution, responsible for collecting and analyzing data - the “Institut National des Statistiques du Burundi (INSB)”. This institution has only recently been able to disaggregate data down to provincial level. It does not have data at hill level. It was therefore necessary to use primary data, especially quantitative data, for agricultural production.

Data analysis

12General data analysis was carried out using mixed triangulation, consisting in reasoning by crossing qualitative and quantitative data. Mixed triangulation provides reliable results that are both quantitatively and qualitatively cross-checked (De Sardan, 2003; Musokotware, 2016). The analysis was also carried out by comparing situations before and during mining activities. Primary data were collected and entered into Excel. Quantitative data were analyzed using descriptive statistics and qualitative data were analyzed by using content analysis (Patton, 2002; Duriau et al., 2007, Srivastava and Thomson, 2009).

Results

Situations

13Livelihoods in the study communities are based on a single income-generating activity - subsistence farming. The absence of viable alternative livelihood activities makes households less able to improve their agricultural production, and to cope with any potential adversity within their livelihoods. Another situation in household livelihoods in the study communities is low income (Table 1).

Table 1. Monthly income from farming before December 2018

|

Income (in BIF) before December 2018 |

Gahoma |

Ruhororo |

||

|

Frequency |

Percentage |

Frequency |

Percentage |

|

|

< 200.000 |

53 |

76 |

49 |

70 |

|

200.000 – 400000 |

16 |

23 |

20 |

29 |

|

400.001 – 620.000 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

Total |

70 |

100 |

70 |

100 |

1$ USD = 2076 BIF (July-August 2022), Source: Data collected by the authors (July-August 2022)

14Before the advent of mining activities, 76% and 70% of the heads of households surveyed in Gahoma and Ruhororo respectively earned less than Burundian francs (BIF) 200,000 ($96 USD) per month from crops without the effects of mining. Among some households (53% and 24% in Gahoma and Ruhororo respectively), this situation is exacerbated by the decline in agricultural production following the effects of mining to which other negative factors external to mining are associated. Prices for agricultural products have almost doubled over the 2017-2021 period as a result of mining activities since December 2018. The products that have become more expensive are those that have been seriously affected by the negative effects of mining, including maize and beans. These crops are generally grown during the rainy season, and are particularly vulnerable to pollution and landslides. As a result of this situation, only 3% (2 households out of 70 households) and 24% (17 households out of 70 households) of the households surveyed were able to double their monthly agricultural income, in Gahoma and Ruhororo respectively. Overall, 89% of the heads of households surveyed in Gahoma and Ruhororo (124 out of 140 heads of households), indicated that their agricultural income was insufficient to enable them to have a good livelihood before the advent of mining activities (Table 2).

Table 2. Sufficient farm income before December 2018

|

Responses |

Gahoma |

Ruhororo |

Total |

|||

|

Frequency |

Percentage |

Frequency |

Percentage |

Frequency |

Percentage |

|

|

Yes |

4 |

6 |

12 |

17 |

16 |

11 |

|

No |

66 |

94 |

58 |

83 |

124 |

89 |

|

Total |

70 |

100 |

70 |

100 |

140 |

100 |

Source: Data collected by the author (July-August 2022)

15This situation was exacerbated by the absence of other income-generating activities (IGA) for households. However, 27% and 51% of households in Gahoma and Ruhororo respectively had slim sources of alternative income (Table 3).

Table 3. Non-farm income sources of households before December 2018

|

Source of income |

Gahoma |

Ruhororo |

||

|

Frequency |

Percentage |

Frequency |

Percentage |

|

|

Other sources of income |

19 |

27 |

36 |

51 |

|

Lack of other sources |

51 |

73 |

34 |

49 |

|

Total |

70 |

100 |

70 |

100 |

Source: Data collected by the author (July-August 2022)

16Most of these were temporary jobs without contracts. These included petty trading, artisanal carpentry, masonry, manual shoemaking, babysitting, sale of agricultural labor, traditional medicine, etc. However, all heads of households with alternative sources in Gahoma and Ruhororo before December 2018, reported that income from these sources was insufficient to improve their agricultural production and sustain livelihoods.

17Another common household livelihood situation was a reliance on a single person - the head of household, for alternative income. Out of 19 households in Gahoma and 36 households in Ruhororo that had alternative incomes before December 2018, 14 households (74%) and 24 households (67%) respectively, were reliant on the head of household alone (Table 4).

Table 4. Members of households involved in alternative activities before December 2018

|

Number of members |

Gahoma |

Ruhororo |

||

|

Number of households |

Percentage |

Number of households |

Percentage |

|

|

5 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

3 |

|

3 |

1 |

5 |

0 |

0 |

|

2 |

4 |

21 |

11 |

30 |

|

1 |

14 |

74 |

24 |

67 |

|

Subtotal |

19 |

100 |

36 |

100 |

|

0 |

51 |

34 |

||

|

70 |

70 |

|||

Source: Data collected by the author (July-August 2022)

Seasonality

18Seasonality is a function of livelihood’s vulnerability in the study communities. Crops are only produced after specific seasons, just as agricultural activities are undertaken on a seasonal basis. This seasonality of agriculture combines with the fact that it is almost the sole IGA of households, to make annual agricultural production low, and livelihoods more vulnerable to potential shocks or disasters. This is amplified by the reliance on a single person for (eventual) alternative income. In the study area, some households did not have good agricultural harvests during the main B cropping season as a result of climatic hazards (especially heavy rains worsening erosion and wash away crops). This situation has left households without other IGA vulnerable. It imposes on them a long lean period before the agricultural harvests of crop season C, even in the absence of shocks or disasters. It also makes it difficult for households, or certain groups of farmers, to repay agricultural loans taken out by mutual aid associations, if the harvests have not been well. This in turn blocks or delays the process of granting agricultural credit by the associations to other households or groups of farmers.

Tendency

19The communities concerned by the study are overpopulated and located in a very hilly locality that is highly susceptible to erosion (Nsabimana, 2019). So, even before December 2018, these communities did not have enough land to cultivate (Pedro, 2011; OECD/FAO, 2016; MAE, 2016; Ndagijimana, 2021). There is no fallowing of land; and crop rotation is by season (MAE, 2016). These factors combine with other negative ones. The latter include the lack of chemical fertilizers, phytosanitary products, adequate agricultural equipment, road infrastructure in good condition, selected and adapted seeds. The communities are also experiencing climatic hazards - especially untimely heavy rainfall in the locality, climate change, illiteracy, the shortage of agronomic supervisors (23 agronomists in a commune of around 17,632 households [INSB, 2020]), etc. All this gives rise to a general downward trend in agricultural production in these communities, in addition to the impacts of the activities of the TMB mining company and the DHDI mining cooperative. The loss of production quantity linked to this trend is estimated at an average of 153 kg per household per year on the two experimental hills (Gahoma and Ruhororo) between the 2017-2018 and 2020-2021 agricultural seasons, as is the case on the reference hill Buhoro.

Natural erosion

20With altitude varying between 1,500 and 2,652 m, the hills covered by the study present a very uneven relief and consequently a very high natural erosion. Land losses are estimated at over 100 tons/ha/year (Nsabimana, 2019). This leads to losses of agricultural production and household livelihoods. The livelihoods of these communities were before the advent of mining activities, and remain vulnerable, in a context of absence of other income-generating sources.

Shock (unusual factor)

21The DHDI local mining cooperative has significant shortcomings in terms of operational capacity and worker skills. Its artisanal mining remains a survival activity, where the workers’ dominant tools are picks and hoes, even though it is a godsend in a very depressed job market, for a significant number of local workers. Apart from a few high school graduates who are diggers for lack of another job, the majority of contract workers are illiterate, as are some of the shareholders who are simply traders who have made a lot of money elsewhere. Other workers are mostly schoolchildren who dig irregularly during the vacations to finance their schooling. The cooperative has no tools or techniques for mineral detection, resorting to intensive digging as a hazardous method of detection (Gaciyubwenge et al., 2024). These shortcomings affect compliance with environmental regulations, the volume of mining production and the scope of rural community development programs. But the cooperative destroys environment less than the foreign company TMB, mainly due to its lower use of chemicals. It cannot exceed 1km2 of exploitation at a time, but begins another exploitation as soon as the previous one is deemed exhausted (AAIB, 2019). TMB has sufficient capacity and skills. But although this would allow it to set up large-scale rural community development programs, it is accused by farmers of the lack of monitoring of the rural projects it has initiated. Its mining concession is 87.87 km2 and produces a lot compared to DHDI. It destroys environment more because of its ignorance of compliance with environmental regulations, and employs small workforce because of its high mechanization (Gaciyubwenge et al., 2024).

22Job creation is their main feature of most interest to local farming households (WB, 2016). TMB employs a total of 250 people, 150 of whom are direct national employees (employees with a contract with the company) including 50 who are native and residents of Gahoma hill where it operates (Gaciyubwenge et al., 2024). These native employees had a monthly salary of 180,000 BIF (i.e. $87 USD, $1 USD = 2076 BIF in July-August 2022). DHDI employs 200 direct workers, all nationals, including 106 natives and residents of Ruhororo hill where it operates. These native workers had a monthly salary of 150,000 BIF (i.e. $72 USD). There are also indirect employees (irregular workers without contracts) who exploit minerals artisanally outside the concessions, but who sell them directly to TMB or DHDI. They can earn between 50,000 BIF and 80,000 BIF per month.

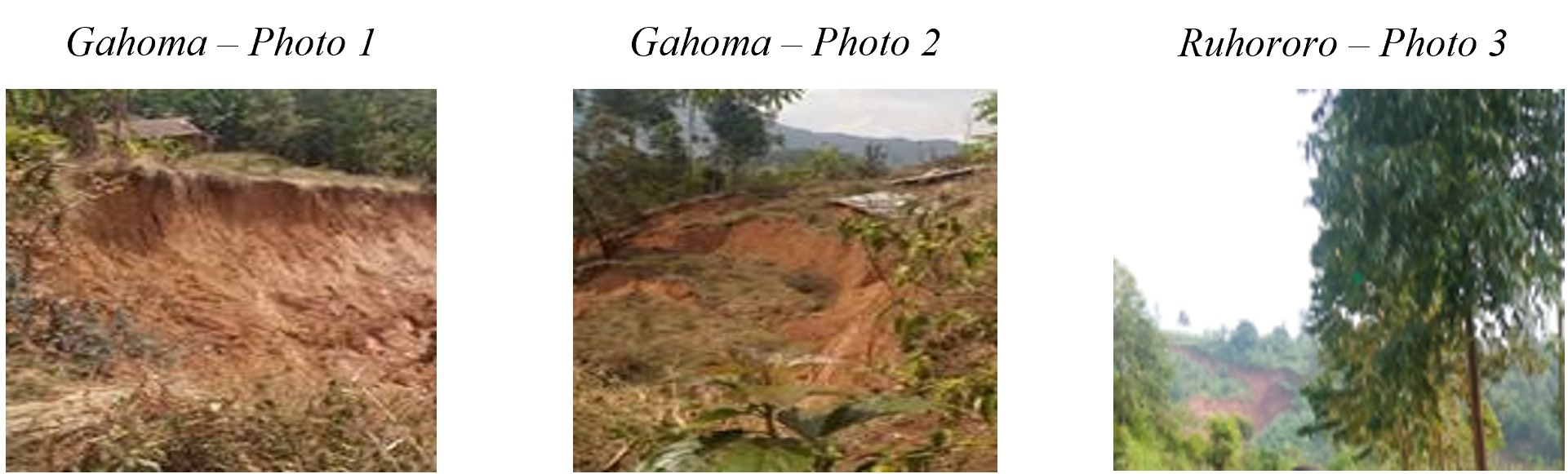

23Mining operations in the study area have had an impact on household livelihoods. The TMB mining company and the DHDI mining cooperative claimed the land on which these rural households undertook their farming activities, as their mining concessions. Mabayi's communal agronomist noted that agricultural land is recognized as an important livelihood asset in these communities. As well as being the basis for undertaking agricultural activities, arable land can also be mortgaged by households to obtain credit and invest in other IGA or activities complementary to farming. In the two experimental communities, 97 households had already lost an average of 0.2 ha of land per household, i.e. a total of 19.4 ha, since the start of mining activities to the survey's moment. Much of this land contained plantations such as banana’s plantations and trees. According to opinion leaders in Gahoma and the communal agronomist, this land grab has reduced activities and livelihoods. In fact, it has led to difficulties in accessing this asset - arable land - as it has caused scarcity and an increase in its purchase or rental price. This land grab and the destruction of plantations, without compensation for a huge number of households, especially in Gahoma, have put severe strains on livelihoods. This has led to hunger and even a livelihood crisis for some households, especially in Gahoma. Land grabbing has also led to households moving long distances to new farmland, thereby reducing their working time. Households were less keen to cultivate perennial or cash crops because of the fear of future land grabbing. This fear gradually increased within households until it became a form of stress (Chambers and Conway, 1991) recognized by the households surveyed in both communities. Indeed, the operations of the TMB company and the DHDI cooperative are constantly taking new concessions intermittently. In addition, the state has not drawn boundary lines to indicate which lands are likely to be taken as mining concessions. These lines are a necessity to dispel the fear of households to cultivate this type of crop on available land. All this has resulted in the loss or weakness of agricultural production and livelihoods in both communities. Some of the households surveyed and the communal agronomist reported that yields had fallen considerably as a result of natural erosion amplified by the DHDI mining cooperative in Ruhororo, and soil pollution by the TMB mining company in Gahoma. Other physical shocks include collapses and landslides that wash away crops and household dwellings as a result of mining activities (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1: Illustration of landslides and loss of crops in Gahoma and Ruhororo

Source: photos taken on site at the time of the survey

24Photos 1 and 2 show the landslides and loss of crops and dwellings near the 'Muhira' river site in Gahoma (Bihahe site). Photo 3 shows landslides and loss of a banana plantation in Ruhororo (Butare site).

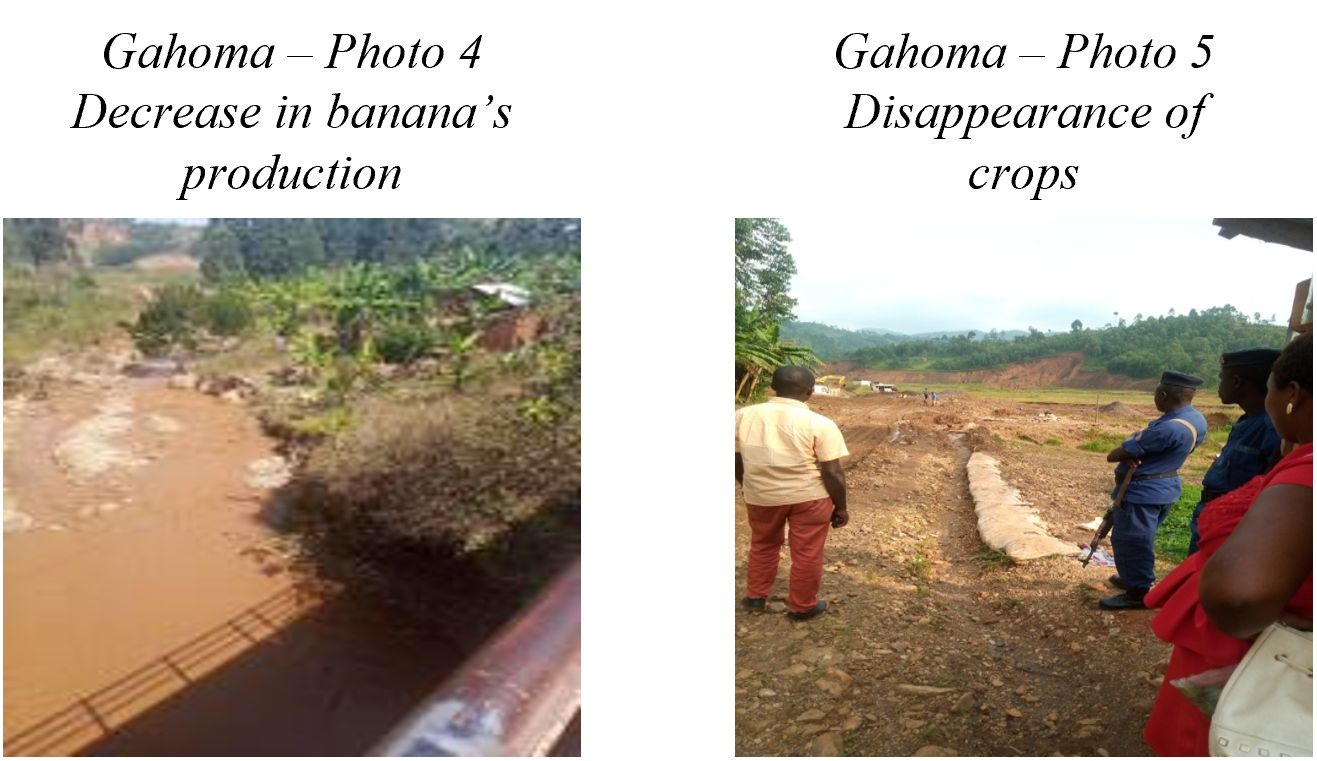

Figure 2: Illustration of the pollution of the groundwater by chemicals and mine tailings; disappearance of sorghum, maize and bean crops in the 'Muhira' river swamp (Photo 4); and reduced production from the banana plantation grown along the river in Gahoma (Photo 5)

Source: Photos taken on site at the time of the survey (Maruri site).

25Photos 4 and 5 show the pollution of the groundwater by chemicals and mine tailings; disappearance of sorghum, maize and bean crops in the 'Muhira' river swamp; and reduced production from the banana plantation grown along the river in Gahoma. These (physical) shocks, in addition to adversely affecting physical and natural assets - arable land - also adversely affect human, financial and social assets. Indeed, our surveys have revealed that water and air pollution cause illness and reduce the health and workforce of household members. Collapses and landslides, water and air pollution reduce production and household finances.

26Households that have lost their land and property and are compensated, received relatively less money compared to the prices of valued agricultural land. They would have received more if they had harvested and sold their crops. Unfair compensation, or the lack of it, leads to famine in some households, and theft from the fields of neighboring households. According to the chief of the hill, this situation leads to unrest within households, and a loss of social ties, especially in Gahoma. These households are unable to acquire new land as a result of the low compensation. The Gahoma hill’s chief commented: "The farmers had worked so hard over the years without expecting this sudden invasion by the TMB company. Everything they had achieved on their monopolized farms, especially the banana and eucalyptus plantations, has been destroyed. But compensation is not enough, and most of them didn't even get the little the company gave them. Now, many are in a situation of poverty and distress". The rising cost of living has become a difficult phenomenon for poor farming households to cope with. The agricultural activities of some households have been curtailed by their inability to access land (which has become more expensive) equivalent to that lost (especially among 15 households in Gahoma who did not receive compensation out of a sample of 35 households who lost land). Other households do not invest compensation payments in the purchase of arable land (03 out of 20 households that received compensation payments in the sample of 35 households that lost land in Gahoma, and 04 out of 17 households that received compensation payments in Ruhororo). Households do not have the power to buy even basic items at high prices due to the relatively competitive incomes of miners. The other reason is that mining activities have led to an increase in demand for goods and services, while agricultural production has generally declined. Prices for these products almost doubled during 2017-2021 in these communities, while the majority of households (97% in Gahoma and 76% in Ruhororo) were unable to double their agricultural income. This situation has worsened livelihoods for households, especially those who received no compensation or assistance in their investment choices.

27These (economic) shocks, in addition to adversely affecting financial assets, also adversely affect natural and human assets. Indeed, the inadequacy or absence of compensation and the high cost of living reduce household members' access to land, good health and healthcare, thereby reducing the workforce, agricultural production and livelihoods.

28The effects of shocks (mines) on assets, resulted in a decrease in the average quantity of agricultural production of 673 kg/household/year (all production combined) on the Gahoma hill, while they resulted in an increase in the average quantity of agricultural production of 17 kg/household/year (all production combined) on the Ruhororo hill, comparing the 2017-2018 and 2020-2021 agricultural seasons, and matching with the Buhoro reference hill. The usual vulnerability factors and other negative factors external to the mines led to a loss in the average amount of agricultural production of 153 kg/household/year on the reference hill. The Gahoma hill lost an overall average production quantity of 826 kg/household/year, generally due to the effects of the activities of the foreign mining company TMB. The Ruhororo hill lost an overall average production quantity of 136 kg/household/year due to the effects of negative factors external to the local mining cooperative DHDI (Table 5).

Table 5. Comparison of agricultural production with the control (reference hill)

|

Gahoma (G) |

Buhoro (B): reference |

Ruhororo |

Horizontal difference from control |

||

|

Average agricultural (kg/household/year) |

Average agricultural (kg/household/year) |

Average agricultural (kg/household/year) |

G%B |

R%B |

|

|

2017-2018 |

2648 |

2230 |

2933 |

Pairing before mining activities |

|

|

418 |

703 |

||||

|

2020-2021 |

1822 |

2077 |

2797 |

Pairing during mining activities |

|

|

-255 |

720 |

||||

|

Vertical differences |

-826 kg |

-153 kg |

-136 kg |

Difference between pairings |

|

|

-673 kg /household /year |

+17 kg |

||||

|

Loss of production quantity linked to trend factor |

-826 kg - (-673 kg) = -153 kg /household/year |

-153 kg /household/year |

-136 kg - (+17 kg) = -153 kg /household/year |

||

Source: Authors' conception

29Despite these average losses in agricultural production, 19 households (12 who had lost land and 7 who had not) and 38 households (10 who had lost land and 28 who had not) had improved their agricultural output thanks to the presence of mining activities in Gahoma and Ruhororo respectively. They had all benefited from capacity-building programmes run by the mining company TMB and the mining cooperative DHDI respectively.

30As part of the community development programs of TMB and the DHDI cooperative in the two study communities, capacity-building projects to improve pig and goat breeding have been implemented. In the agricultural sector, projects to introduce maize cultivation during the B cropping season have been carried out. In the same context, farmers' associations and mutual financial assistance associations have also been set up in both communities. Schools, clean water sources and a health center have also been built or upgraded in the Ruhororo community by the DHDI cooperative. In addition, some members of the households have had jobs with the TMB company or the DHDI cooperative.

Discussion

31The aim of this article is to provide an analysis of the habitual factors of vulnerability, the role of mining activities on the assets of rural households in the presence of these factors, and hence on their agricultural production on the Gahoma and Ruhororo hills of Mabayi commune, where the Russian company TMB and the local cooperative DHDI have been operating respectively since December 2018. The activities of farming households were analyzed in terms of five vulnerability factors, including historical or habitual factors (situations, seasons, trends, natural erosion) and factors linked to mining activities. The latter are unusual vulnerability factors in that households were not well informed about the advent of these activities in the area, resulting in unexpected losses for some households (Ellis, 2000; Chambers and Conway, 1991). The five vulnerability factors affect the assets or capital - physical capital, human capital, financial capital, natural capital and social capital - that sustain the livelihoods of rural farmers (Carney, 1998; DFID, 1999; Ellis, 2000).

32In rural areas of developing countries, arable land is the most important asset that secures farmers' livelihoods (FAO, 2011; Sali 2012; Tsue et al., 2014). Indeed, successful productivity growth in agriculture has been the source of early development, structural transformation and subsequent industrialization in most developed countries (De Janvry and Sadoulet, 2019). In developing countries in general, and in Burundi in particular, farming conditions remain unfavorable to productivity. Agriculture is rain-fed, seasonal and subject to climatic hazards. Other negative factors for productivity are the lack of chemical fertilizers, the lack of phytosanitary products, the lack of selected and adapted seeds, the lack of adequate agricultural equipment, the lack of road infrastructures in good condition, the shortage of agricultural supervisors, illiteracy, etc. In addition, demographic pressure is leading to the fragmentation of arable land and unfavorable farming conditions. In Malawi, for example, farmland for households engaged in agricultural production fell from 2.3 acres in 2004 to 1.8 in 2010 and 1.4 in 2016 (De Janvry et al., 2022). Under such conditions, agricultural transformation (the diversification of farming systems towards high-value crops that are resistant to climatic shocks and/or perennial) and rural transformation (the creation of added value through non-agricultural activities linked to farming in rural areas) is liable to mitigate the vulnerability of rural farmers (De Janvry and Sadoulet, 2019).

33In African countries (Burundi, Rwanda, Ghana; Uganda, Tanzania, etc.), the head of household (in this case, the husband) is considered to be the provider of all means of livelihood. Moreover, the differentiation (male/female) of land rights and the concentration of land in the hands of men mean that daughters' inheritance rights are contested. This situation places women at a disadvantage, especially when it comes to family decision-making, as men are often solely responsible for decisions (Quan et al., 2004). Empowering women and raising men's awareness of women's intrinsic role in production is likely to boost household livelihoods and reduce the vulnerability of rural households.

34Arable land is both a natural and a physical asset. If it is destroyed, or appropriated and not properly compensated for in a timely manner, this constitutes a deprivation of the natural asset from which the rural activity of farming is undertaken as the principal (and almost sole) means of livelihood (Adjei, 2007). The introduction of a more efficient and effective arable land title registration system to enhance land tenure security on arable land secures rural farmers (Tsue et al., 2014). The advent of mining activities in the communities concerned by the study constitutes a physical and economic shock. This unpredictable event directly destroyed assets and/or affected the rural farmers themselves (Ellis, 2000). For some farmers, these shocks were sudden and traumatic (Chambers and Conway, 1991). The advent of mining activities was a shock because households were not prepared for it. It led to land grabbing, destruction of plantations, soil pollution in the vicinity of sites, erosion, collapses and landslides, and put pressure on the livelihoods of households who lost their agricultural production quantities. In addition, there has been a loss of income that would have been earned by households and invested, had the agricultural production been consumed and/or marketed (Zabsonré et al., 2016).

35The study revealed that households who have lost part of their land to mining activities, and who have not purchased additional land to replace it, are practicing less farming. The farms of those who have not lost land and who live close to mining sites, suffer the negative effects of these activities. In these cases, agricultural production is inferior to that in non-mining areas. In addition farm labor is becoming scarcer and more expensive. As a result, a household living in a mining community is more likely to be vulnerable to poverty than an identical household living in a non-mining community. This situation is driving up food prices, making life more expensive for rural households. Indeed, the number of consumers of basic goods and services has increased due to the establishment of mining companies, while production has decreased (Bhattacharya, 2012; Assan and Muhammed, 2018).

36The negative environmental and social impacts of mining can far exceed macroeconomic performance (Akabzaa and Darimani, 2001). Lack of or inequitable compensation, the withdrawal of rural farmers from their farming areas, environmental pollution, erosion, etc. are prone to keep rural households in poverty (Aragon and Rud, 2012). National mining policy must be based on participatory governance, consensus and transparency. It must take into account the opinions of the most vulnerable when making decisions, while fulfilling the present and future needs of society (Lugoe, 2010, 2012). It must ensure the satisfaction of all stakeholders, including mining companies (TMB and DHDI), the State, local communities located in and/or around mining zones, and in particular the owners of arable land in which mining activities take place. The government therefore needs to develop a mining policy that balances the expectations, needs and wishes of all stakeholders involved in mining. Revenues derived from mining through various fiscal instruments such as royalties and taxes must achieve reasonable, healthy economic growth and sustainable development (Lugoe, 2012; Samuel, 2023).

37Although the advent of mining activities is considered as a shock, it positively affects the assets of some households (Adjei, 2007, Assan and Muhammed, 2018). Thanks to mining companies' commitments in a given area, mining activities stimulate the agricultural sector and improve the livelihoods of rural households (Adjei, 2007; Zabsonré et al., 2016; DFID and ePact, 2019). The community development projects of the TMB company and the DHDI cooperative have positive socio-economic effects in the two communities studied. They positively affect human, financial and social assets. Indeed, capacity building in the agriculture and livestock sector has improved farmers' skills, and improved finances through increased agricultural production. The construction and rehabilitation of social infrastructure has improved the knowledge, health and work capacity of household members (Adjei, 2007, Assan and Muhammed, 2018). It is this mining company and cooperative which encourage farmers to form farmers' associations, leading to improved production and finances. They also improve social ties by promoting grouping in producers' associations/cooperatives. Mutual financial assistance associations help improve finances and production by granting agricultural credit to households. They also improve social ties by providing financial assistance in the event of an idiosyncratic shock (an illness or death for example). Job creation in the mining sector provides wages that also improve household finances.

38The study was conducted after only three agricultural campaigns. This makes prudent, for all intents and purposes, the interpretation of results in terms of addition or loss of quantity of agricultural production. Thus, especially for the local cooperative DHDI, although the addition of 17 kg can be attributed to it, this quantity is so insignificant to say that it is efficient. It could in long term lead to loss, when it will have exploited a large area and used a lot of chemicals in the same way as TMB company, if attention is not a priority.

Conclusion

39Livelihoods in the study communities are generally and usually characterized by a single branch of IGA: farming. This situation weakens, even before the advent of mining activities, the livelihoods of households, as the low income derived from these activities does not allow them to meet their needs without any viable alternative source. Farming for these survival activities is carried out according to specific seasons, thus undermining annual production and household livelihoods. They may, for example, experience a long lean season, with little income between two successive seasons, in the event of hazards or climatic changes during the previous season. In addition, the few households that had some slim alternative income before the advent of mining activities were generally dependent on the head of household. Before the advent of mining, this undermined, and still undermines agricultural production and the livelihoods of these households. The other usual factor of vulnerability of households with regard to their activities and livelihoods, which already existed before the advent of mining activities, is the downward trend in agricultural production. This is due to the progressive reduction of farmland resulting from overcrowding in these communities, and to other negative external factors generally linked to the absence or weakness of agricultural subsidies from the State. Added to this is the factor of natural erosion due to the very uneven relief that characterizes the hills of the communities in the study, leading to crop and agricultural production losses in the event of heavy rains.

40Before the advent of mining activities in both communities, livelihood activities were carried out in a context of vulnerability linked to the four usual factors: situations, seasons, trends and natural erosion. Mining came as a shock, as the farmers were unprepared for its advent, which was not the result of any compromise to which they would have agreed. This shock, which was an almost unpredictable and unusual event (unusual vulnerability factor) on the assets, added to the four usual factors, and is subdivided into physical shocks and economic shocks. With regard to physical shocks, mining activities in both communities have led to the loss and destruction of land (through pollution, erosion, collapses and landslides) for some households. This has resulted in the loss of housing and crops for some households, and thus the loss of agricultural production and livelihoods. The main economic shock identified by the study is the rising cost of living, which makes it difficult for households in these communities, especially those who have lost land (and assets) and who have not received compensation or assistance in their investment choices, to obtain viable livelihoods. Inclusive and/or participatory governance for all stakeholders would constitute viable and sustainable socio-economic development for future generations. The advent of mining activities is seen as a shock or vulnerability factor in rural communities. But it has both positive and negative effects on assets. Some households have benefited (as a result of positive effects/impacts) from this development, while others have been victims. Overall, the activities of the foreign mining company TMB reinforced the effects of negative external factors by contributing negatively (-673 kg/household/year) to the reduction in average agricultural production experienced on Gahoma hill (-826 kg/household/year), while the activities of the local mining cooperative DHDI mitigated the effects of negative external factors by contributing positively (+17kg/household/year) to the reduction in average agricultural production experienced on the Ruhororo hill (-136 kg/household/year). This raises questions about the long-term future of agriculture and livelihoods on Gahoma hill, which is already experiencing a large loss of agricultural production due generally to TMB's mining activities, among a significant number of households (53% of sample households), if mining sector management and external negative factors remain the same. But also, attention must be paid to the local DHDI cooperative. The addition of 17 kg to average quantity of agricultural production per household does not reassure about its long-term effectiveness.

Bibliographie

ActionAid International Burundi-AAIB (2019). Etude sur la mobilisation des ressources internes et la gouvernance des ressources naturelles au Burundi. Rapport final. Aussi cité: Ndikumana J.B., Mbonicuye D. (2019). Etude sur la mobilisation des ressources internes et la gouvernance des ressources naturelles au Burundi. Rapport final.

Adjei E. (2007). Impact of Mining on Livelihoods of Rural Households. A Case Study of Farmers in the Wassa Mining Region, Ghana. MPhil Thesis in Development Studies, Submitted to Department of Geography, Norwegian University of Science and Technology.

Akabzaa T., Darimani A. (2001). Impact of Mining Sector Investment in Ghana: A Study of the Tarkwa Mining Region. Structural Adjustment Participatory Review International Network (SAPRIN), Washington DC.

Alhasan I.A. (2014). Galamsey and the Making of a Deep State in Ghana: Implications for National Security and Development. Research on Humanities and Social Sciences, no 16, vol. 4, pp. 47-56.

Aragon F.M., Rud J.P. (2012). Mining, Pollution and Agricultural Productivity: Evidence from Ghana. Working papers. ISSN 1183-1057.

Assan J.K., Muhammed A-R. (2018). The impact of mining on farming as a livelihood strategy and its implications for poverty reduction and household well-being in Ghana. International Journal of Development and Sustainability, vol. 7, n°1, pp. 1-20. SSN: 2186-8662.

Bhattacharya J. (2012). Planning Efforts to Challenge and Avert Local Resource Curse in Mining Areas, Revista Minelor / Mining Revue, no 4, vol. 18, pp. 22-30.

Bouchard V. (2011). Echantillonnage, Méthode, Représentativité, Sondage, Statistique. https://blogue.som.ca/determiner-taille-optimale-echantillon/.

Carney D. (1998). Implementing the Sustainable Rural Livelihood Approach, Chapter 1 pp. 3-23, in Carney D. (ed). Sustainable Rural Livelihoods, What contributions can we make? Department For International Development (DFID), London, UK.

Chambers R., Conway G. (1991). Sustainable Rural Livelihoods: Practical Concepts for the 21st Century, Universit of Sussex, Institute for Development Studies, IDS Discussion Paper 296, Brighton.

De Janvry A., Sadoulet E. (2019). Transforming developing country agriculture: Removing adoption constraints and promoting inclusive value chain development. Development policies, working paper, n° 253.

De Janvry A., Duquennois C., Sadoulet E. (2022). Labor Calendars and Rural Poverty: A case study for Malawi. Food Policy 109, 102255, University of California at Berkeley. DOI: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2022.102255.

De Sardan J-P.O. (2003). L'enquête socio-anthropologique de terrain: synthèse méthodologique et recommandations à usage des étudiants, Etudes et travaux, n° 13, pp. 1-58.

DFID (1999). Sustainable Livelihoods Guidance Sheets. Sections 1 and 2. Available from DFID Support Office (livelihoods@dfid.gov.uk) or from the livelihoods website (www.livelihoods.org).

DFID; ePact (2019). Artisanal-small-scale mining-agriculture linkages. Decision Support Unit (DSU), Final Report, Kivu, DRC.

Duriau V.J., Reger R.K., Pfarrer M.D. (2007). A Content Analysis of the Content Analysis Literature in Organization Studies: Research Themes, Data Sources, and Methodological Refinements. Organizational Research Methods, no 10, pp. 5-34. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428106289252.

Ellis F. (2000). The Determinants of Rural Livelihood Diversification in Developing Countries. Journal of Agricultural Economics, no 2, vol. 51, pp. 289-302. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1477-9552.2000.tb01229.x.

FAO (2011). Land tenure and international investments in agriculture. A report by The High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition, Rome.

Gaciyubwenge E., Burny P., Bitama P.C. (2024). Mine’s Characteristics and Their Links with Agriculture as the Main Livelihood for Rural Households in Burundi. Academic Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies, no 4, vol. 13, pp. 137-156. DOI: https//doi.org/10.36941/ajis-2024-0105.

Groupe de la Banque Mondiale-BM (2016). Transparence des revenus de l’exploitation minière artisanale et à petite échelle liée à la production d’étain, de tantale, de tungstène et d’or au Burundi. Washington, DC. Rapport final. Aussi cité : Perks R., Karen H. (2016). Transparence des revenus de l’exploitation minière artisanale et à petite échelle liée à la production d’étain, de tantale, de tungstène et d’or au Burundi. Washington, DC : Banque mondiale. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.103.5.1759.

Institut National des Statistiques du Burundi -INSB (2020). Projections démographiques au niveau communal, 2010-2050.

Institut National des Statistiques du Burundi -INSB (2021). Profils et déterminants de la pauvreté au Burundi. Rapport de l’enquête intégrée sur les conditions de vie des ménages au Burundi (EICVMB, 2019-2020).

Lugoe F.N. (2012). Governance in mining areas in Tanzania with special reference to land issues. The Economic and Social Research Foundation (ESRF), Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. ESRF Discussion Paper n° 41.

Lugoe F.N. (2010). East Africa’s Initiatives in Natural Resource Governance. Paper Presented to the Regional Conference on “Networking for Natural Resource Governance in Africa”: Towards a Regional Approach. 27th- 29th January 2010. Alisa Hotel. Accra.

Ministère de l’Agriculture et de l’Elevage (2016). Plan National d’Investissement Agricole au Burundi 2016-2020.

Ministère de l’Environnement, de l’Agriculture et de l’Elevage (2022). Analyse IPC de l’insécurité alimentaire aiguë au Burundi, Rapport Juin-Décembre 2022.

Mokam A., Tsikam C. (2017). Impacts de l’exploitation artisanale de l’or sur les populations de Kambélé, Région de l’Est Cameroun, Université Catholique d’Afrique Centrale, Centre d’excellence pour la gouvernance des industries extractives en Afrique francophone, 30 p.

Musokotware S.I. (2016). The socio-economic impact of mining: a comparative study of Botswana and Zambia. Philosophy thesis in management, Witwatersrand Business School, University of Witwatersrand.

Ndagijimana M. (2021). Coping with risk and climate change in farming : exploring and Index-based crop Insurance in Burundi. PhD thesis, Wageningen University, Wageningen, the Netherlands. DOI: 10.18174/533040.

Nsabimana A. (2019). Pratiques d’orpaillage et érosion des sols à Mabayi, au Burundi. Sciences de l’environnement. hal-02098899. https://auf.hal.science/hal-02098899.

OCDE (2016). Coopération pour le développement : Investir dans les objectifs de développement durable, choisir l’avenir, Editions OCDE, Paris.

OCDE/FAO (2016). L'agriculture en Afrique subsaharienne : Perspectives et enjeux de la décennie à venir, Partie I, Chapitre 2, pp. 63-104, dans Perspectives agricoles de l'OCDE et de la FAO 2016-2025, Éditions OCDE, Paris.

Patton M.Q. (2002). Qualitative Research and Evaluation Method. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publication. Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40319463.

Pedro P.S. (2011). Investir dans l’agriculture au Burundi : Indispensable pour combattre l’insécurité alimentaire et améliorer les conditions de vie des femmes paysannes. Senior Researcher.

Quan J., Tan S.F., Toulmin C. (2004). Land in Africa Market Asset or secure livelihood? Proceedings and summary of conclusions from the Land in Africa. Conference held in London, November 8-9, 2004.

Sali G. (2012). Agricultural Land Consumption in Developed Countries. Research in Agricultural and Applied Economics. Department of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences, University of Milan.

Samuel A.Y. (2023). Digging Deeper: The Impact of Illegal Mining on Economic Growth and Development in Ghana. Munich Personal RePEc Archive (MPRA). https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/117641/.

Srivastava A., Thomson S.B. (2009). Framework Analysis: A Qualitative Methodology for Applied Policy Research. JOAAG, vol.4, n°2, pp.72-79.

Todd E. (1999). La diversité du monde. Famille et modernité, Publication Paris, Editions du Seuil.

Tsue P.T., Nweze N.J., Okoye C.U. (2014). Effects of Arable and Tenure and Use on Environmental Sustainability in North-Central Nigeria. Journal of Agriculture and Sustainability, vol.6, n°1, pp. 14-38.

Vircoulon T. (2019). Mutation du secteur minier au Burundi: du développement à la captation. Notes de l’Institut français des relations internationales, Ifri, no/ISBN: 979-10-373-00021-8.

World Bank (2015). Socioeconomic Impact of Mining on Local Communities in Africa, Technical Report, no ACS 14621. Also cited: Andersson M., Punam C-P., Dabalen A.L., Land B.C., Sanoh A., Smith G., Tolonen A.K., Aragaon F., Kotsadam K.A., Hall O., Olén N. (2015). Socioeconomic Impact of Mining on Local Communities in Africa. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.1.1357.7446.

Yoann M. (2021). Méthode d’échantillonnage dans les études épidémiologiques transversales nationales auprès des professionnels de santé en France, application odontologie. Thèse en Santé publique et épidémiologie. Université Montpellier. https://theses.hal.science/tel-03384092.

Zabsonre A., Agbo M., Some J., Haffin I. (2016). Impacts de l’exploitation de l’or sur les conditions de vie des populations au Burkina Faso. Partnership for economic policy, no 145.

Pour citer cet article

A propos de : Egide Gaciyubwenge*

Laboratory of Economics and Rural Development, Gembloux Agro-Bio Tech, University of Liege, egidegaciyubwenge@yahoo.fr

A propos de : Philippe Burny

Laboratory of Economics and Rural Development, Gembloux Agro-Bio Tech, University of Liege, Philippe.Burny@uliege.be

A propos de : Pierre Claver Bitama

Economics Faculty, Higher Institute of Military Executives, pierreclaverbitama@yahoo.fr