University museums, inclusion and territory: a case study of Espaço do Conhecimento UFMG1

Résumé

Cette présentation étudie la relation entre l'inclusion socioculturelle et le territoire, en prenant comme exemple le musée universitaire ECUFMG. ECUFMG est dédié à la diffusion culturelle et scientifique. Il intègre un ensemble d'équipements stratégiquement situés dans une zone centrale de la ville de Belo Horizonte en raison d'une politique publique visant à promouvoir la culture. Les principales questions de l’étude sont les suivantes: L’ECUFMG est-il capable de briser les barrières invisibles liées à la structure sociale circonscrite sur le territoire physique ? Est-il fréquenté par divers profils de publics ? L’étude de terrain montre que les barrières sociales et culturelles limitent l’accès des visiteurs au musée. Nous avons trouvé un profil homogène parmi les visiteurs spontanés (lycée, revenus élevés et habitudes culturelles élevées, quel que soit leur lieu de résidence), soulignant la barrière invisible d'accès, liée aux questions d'appartenance et de reconnaissance, ainsi que le manque d'informations sur ECUFMG et ses activités. Le public scolaire se rend au musée grâce à une politique éducative de planification de visites. Celle-ci atteint dès lors toutes les classes sociales et tous les âges. Ces visites scolaires restent le moyen principal pour toucher le public le plus représentatif possible de la société. Les visites programmées nécessitent également des approches et des méthodologies pédagogiques favorisant le dialogue sur les connaissances acquises et leur appropriation par un public scolaire large et diversifié.

Abstract

This presentation investigates the relationship between sociocultural inclusion and territory, taking the university museum ECUFMG as a case study. ECUFMG is a space dedicated to cultural and scientific dissemination. It integrates a set of equipment strategically located in a central area of the city of Belo Horizonte due to a public policy focused on culture promotion. The guiding questions of this study were: Is ECUFMG able to break the invisible barriers related to social structure circumscribed in the physical territory? Is it frequented by diverse public profiles? The field study points out that social and cultural barriers limit the access of visitors to the museum. It was found a homogeneous profile among spontaneous visitors - high schooling, high income and high cultural habit, regardless of place of residence -, pointing out invisible barrier to access, concerning questions of belonging and recognition, as well as lack of information about ECUFMG and its attractions. Nevertheless, the public from schools, who goes to the museum through an educational policy of scheduling visits, reaches all sorts of social classes and ages. This is the main way the museum can encourage an audience as representative of social reality as possible. Moreover, scheduled visits also require educational approaches and methodologies that stimulate the dialogue about knowledge produced and ensure their appropriation by a broad and diverse school audience.

Introduction

1Culture is manifested in the territory, and it is the main means of use and enjoyment of the city and its various spaces. Artistic-cultural manifestations are opportunities to experience the space, to undergo and to appropriate it. Therefore, taking the city through culture – the Party dimension corresponding to Lefebvre’s spatial triad - can also be characterized as a form of social emancipation (Lefébvre 1991, 1996). In this perspective, the debate on the role of cultural spaces, where creativity, self-expression, social cohesion, and respect for diversity are stimulated and diffused, is relevant on both public and academic spheres. In a similar manner, the access restriction to those cultural space is a compelling topic.

2

3Accordingly departing from this reflection, the university museum Espaço do Conhecimento UFMG (Federal University of Minas Gerais) –ECUFMG – is the case studied in this article. In the research carried out through the application of questionnaires and semi-structured interviews, we investigated the profile of the audience that frequents the museum, as well as its interfaces with the city of Belo Horizonte. Given the location of this equipment in the central area of the city, it was explored whether ECUFMG can break the social structure circumscribed in the physical territory, breaking the invisible barriers of access and, thus, being frequented by diverse groups.

4

1. Culture, Consumption and Territory

5Culture is a local phenomenon; it is the manifestation and invention of the territory. The city is a cultural phenomenon, a locus of encounters, exchanges, and diversity (Rubim 2010, Lefébvre 1996). Therefore, to think about culture is to think about the territory.

6

7Pierre Bourdieu’s concept of habitus, understood as a set of interferences that individuals receive throughout their lives, regards the relationships constructed within family, with neighbors, and at school, and which form their propensities to act, whether in the economic, social or cultural sphere. Each habitus is singular, but there are deep similarities between habitus of correlated persons, which can be distinguished in a symbolic social space. The author observed that cultural consumption – especially considering fine arts – is a mechanism for maintaining social hierarchy since it incorporates a criterion of distinction. In other words, even a museum that has free access can impose other forms of restriction (non-economic), establishing an invisible barrier, often related to such individual’s habitus (Bourdieu 1984).

8

9Cultural consumption can be seen as a socio-cultural process in which a system of differentiation is effective. For Bourdieu (1984), it is in the symbolic space – where the objective and subjective social differences are manifested – that validations of social hierarchy occur through the struggles between individuals to establish their positions and representations. Interactions are defined by an accumulation of capital, whether in its financial, cultural, educational, or human form (Bourdieu 1984).

10

11According to Bourdieu (1996), the locus occupied by an agent is an excellent indicator of its position in the social space because it is the result of its inscription in the physical space. The construction of social space occurs, then, through the spatial distribution of groups and agents according to their positions, which are differentiated, mainly, in two principles: control of economic and cultural capital. Moreover, it is critical to think of a power over space that comes from these forms of capital (Bourdieu 1996, 1984). This aspect is be related to what Lefebvre (1991) conceptualized as the production of space. For the author, all the citizens of a city are involved in producing space to a greater or lesser degree. What changes between groups is how one can enjoy all that the city offers, while others are denied this right to the same space (Lefébvre 1991, 1996)?

12

13The right to the city, which can also be considered the right to urban life, takes place entirely in the urban space, locus of the dialectical triad: political power, economic surplus, and party (Monte-Mór 2005, Lefébvre 1996). For Lefébvre (1996), despite political and economic power being concentrated, the party – interpreted as the cultural dimension of urban life – is a collective experience lived in the city. Indeed, the Party – widely understood as cultural manifestations – is a phenomenon of exchange, of encounter, of diversity, of exacerbation of social relations, the ultimate expression of what the city is.

14

2. Case Study: Espaço do Conhecimento UFMG

15Espaço do Conhecimento UFMG is a cultural space of the Federal University of Minas Gerais. It is not exactly a museum sensu stricto, but rather a « differentiated cultural space, which simultaneously combines culture, science, and art »2. Currently, ECUFMG is operated by a partnership between the state government and the Federal University of Minas Gerais. It is also counting on the sponsorship of private companies through the Federal Law of Incentive to Culture.

16

17ECUFMG is a center for training, dissemination, and dialogue between the university and the non-academic community, where the visitor interacts with scientific and artistic knowledge as well as traditional knowledge. In its mission to merge science and everyday life, ECUFMG has a Planetarium, an Astronomical Terrace, and a Digital façade, in addition to the long-term and temporary exhibitions. There is also an extensive range of debates, workshops, and other educational activities that attract audiences of different age groups, diverse realities, and broad interests.

18

19Moreover, ECUFMG is part of the Circuito Liberdade, a cultural complex located in the vicinity of Praça da Liberdade, in Belo Horizonte. Praça da Liberdade is a milestone in the history of Belo Horizonte since its construction plan, representing its civic center, is a feature reinforced by public buildings that began to shape its surroundings some years after its conception in 1898. In 1997, it was proposed that these buildings become cultural centers, while the state administration no longer seemed to fit in that place. Then, in 2003, it was announced the transfer of the secretariats and public agencies to a new headquarters, the Administrative City, inaugurated in 2010 when the Circuito Liberdade was also launched. Circuito Liberdade currently has more than fifteen facilities, including museums, cultural and training centers, which engages with the diversity of the artistic universe of Minas Gerais. It has consolidated itself as an instrument of public cultural policy of the state.

20

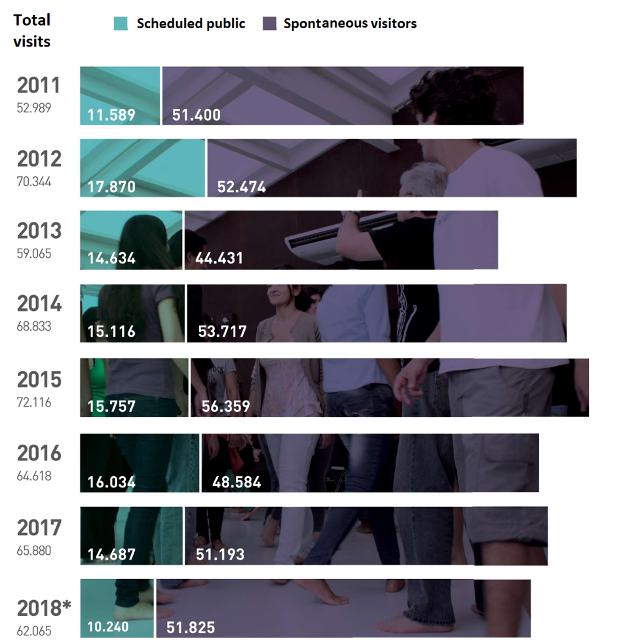

21ECUFMG was inaugurated on March 21, 2010. Since its opening, more than 350.000 people have visited the museum (fig. 1). There are two groups of visitors: spontaneous and scheduled. Spontaneous visitors are those who go to the museum without prior scheduling. In contrast, the scheduled ones are mostly public schools that take their students to visit the museum, as well as other special groups.

22

Figure 1 – Audience of ECUFMG since its inauguration. Photo: Espaço do Conhecimento UFMG’s Porfolio.

23

2.1. Methodological aspects

24This article is connected to the research project « Public Study of Espaço do Conhecimento UFMG ». The survey, carried out in 2017, had 272 questionnaires applied from a random sample, between April 5 and June 3, 2017. The questionnaire had multiple choice and short answer questions and sought to investigate the socioeconomic profile of the adult visitors and their perception of the museum.

25

26There were also semi-structured interviews with four members of the ECUFMG team and twenty spontaneous visitors, comprising 17 residents of all regions of the municipality of Belo Horizonte and three residents of other municipalities of the Belo Horizonte Metropolitan Region (RMBH). These interviews aimed to investigate in greater depth the correlations between the role of ECUFMG and the concepts and ideas presented in the theoretical part of the research, especially questions that were not thoroughly addressed in the questionnaires at the first phase of the study.

27

28Finally, the « participant observation » method was adopted during the research. This method establishes the importance of the contact between the observer and the social field being observed. This allows for greater involvement of the researcher by sharing more subjective processes with the individuals due to a face-to-face interaction (Haguette 2001, Gil 2008). This was the case here since the authors, as members of the aforementioned research project, were responsible for elaborating and applying part of the questionnaires.

29

2.2. Results

2.2.1. Profile of visitors

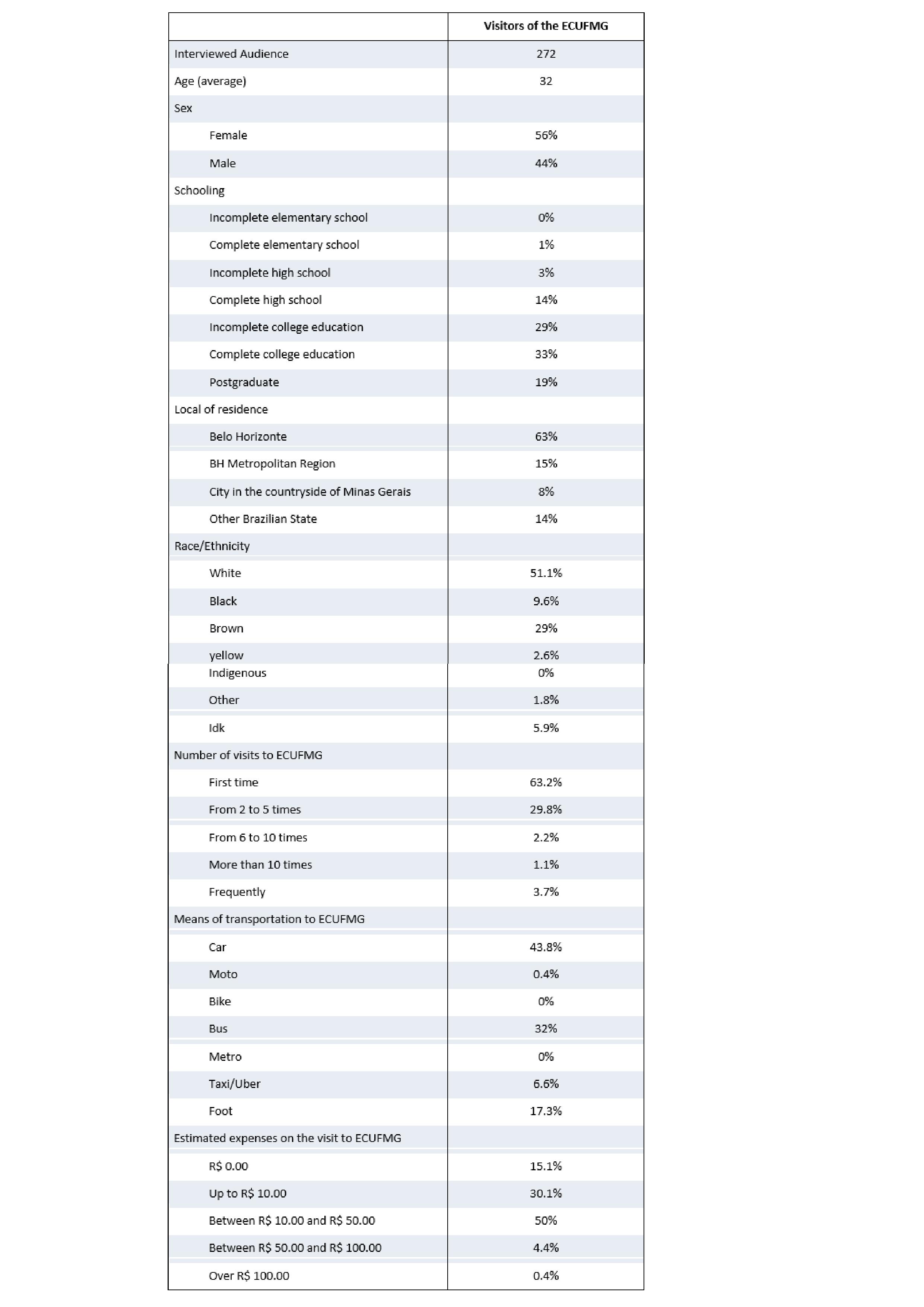

30Table 1 describes the general profile of ECUFMG’s spontaneous audience.

31

Table 1 – Socioeconomic characteristics and visit conditions of ECUFMG’s spontaneous audience. Photo: Elaborated by the authors, based on data from the survey « Public Study of Espaço do Conhecimento UFMG », 2017.

32

33The majority of the interviewed public (63.2%) were visiting for the first time, while only 3.7% reported visiting the space frequently. Most of the audience is between 18 and 35 years old, female, and considered white. ECUFMG receives mostly graduated students or students in higher education (33.5% and 29%, respectively). Further, a significant number of the audience has completed postgraduate studies (19%), representing a high result compared to the percentage of the Brazilian population with this level of education, which is around 1% (IBGE, 2010). These figures agree with the literature, which indicates a strong correlation between the level of consumption of artistic-cultural goods and the level of schooling in Brazil (Diniz & Machado 2011).

34

35Another point addressed in the questionnaire is how the visitors arrived at the museum and how much they spent on the visit, considering the indirect expenses of transportation and food, among others. 43.8% used the car to go to the museum, 32% went by bus, and 17% went on foot. These numbers may reflect the museum’s proximity to the place of residence, study, or work of the visitors, as well as ease of access. Despite being a free space, only 15% say they have not spent any money on the visit, while 50% say they have spent between R$ 10.00 and R$ 50.003.

36

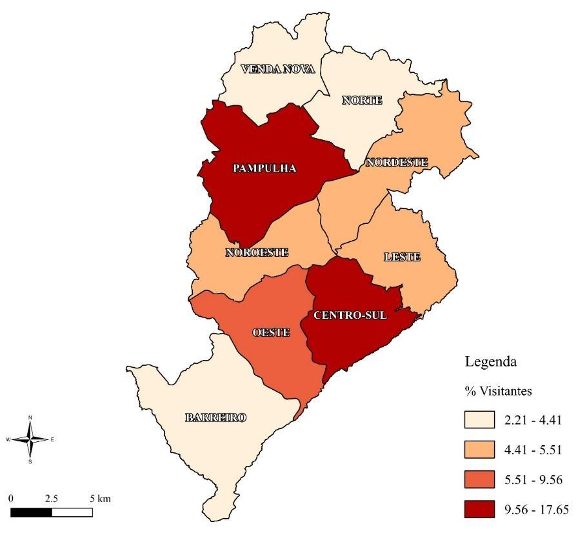

37Figure 2 shows the distribution of spontaneous visitors according to the region of residence in the city of Belo Horizonte. It should be noted that there are two regions with the highest concentration of visitors: Centro Sul – center South (17.6%) and Pampulha (10%). These are the places that concentrate the high-income population in Belo Horizonte. The second-largest share of visitors (15.1%) comes from other municipalities in the Metropolitan Region of Belo Horizonte (RMBH), while 22% come from the state's interior and other states and countries.

38

Figure 2 – Spontaneous ECUFMG’s visitors according to their regional residence (BH). Photo: Elaborated by the authors, based on data from the survey « Public Study of Espaço do Conhecimento UFMG », 2017.

39

2.2.2 Additional perceptions from interviews and participant observation

40Broadly, interviewed visitors highlight that interest in culture is the most important factor for the visit to take place, prevailing over the specific location. The interviewees, especially those who classified themselves as « simple », « peripheral », also reflect on the difficulties involved in access and appropriation, which includes but goes beyond the factor of distance, cost of transport, etc. They raise questions about belonging, strongly related to the act of consuming culture, since, as discussed earlier, the concept of belonging is inherent in the right to citizenship and linked with the struggle for acquisition and enjoyment of cultural goods and services.

41

42Another relevant aspect is that respondents consider themselves as « cultural consumers ». When asked about the factors and variables that influenced it, they mention their school, any formal education, degrees earned, the role of parents, family, and friends, as well as the idea of addiction – the more you consume, the more you will consume. Some visitors claim that they came to the museum for their children, meaning they intend to form the habit in their children, while others were brought by their children who often got to know ECUFMG through their schools. In the latter case, it is also possible to have a habit formed contrary to what is found in the literature, in which children and young people influence family members to experience culture.

43

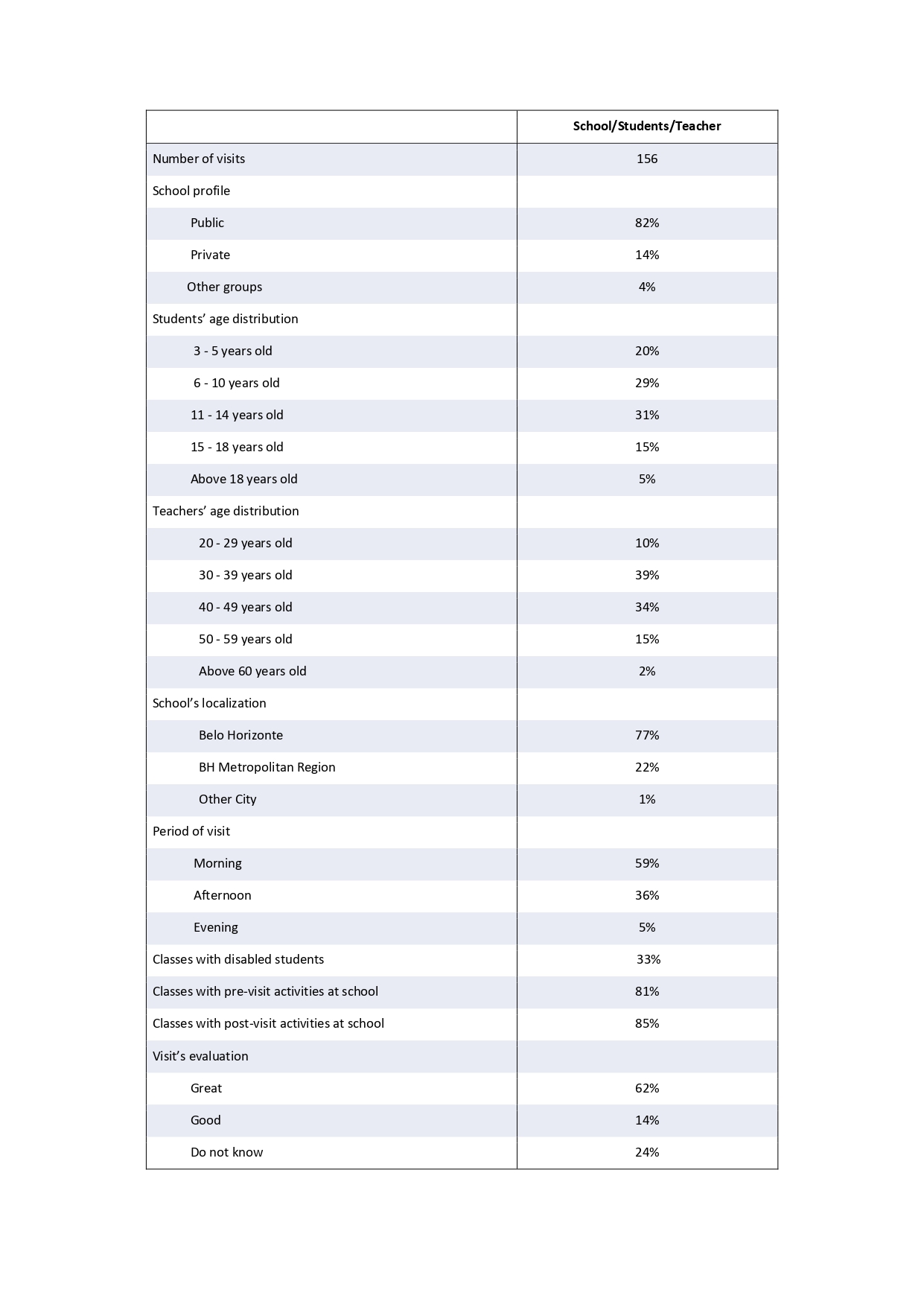

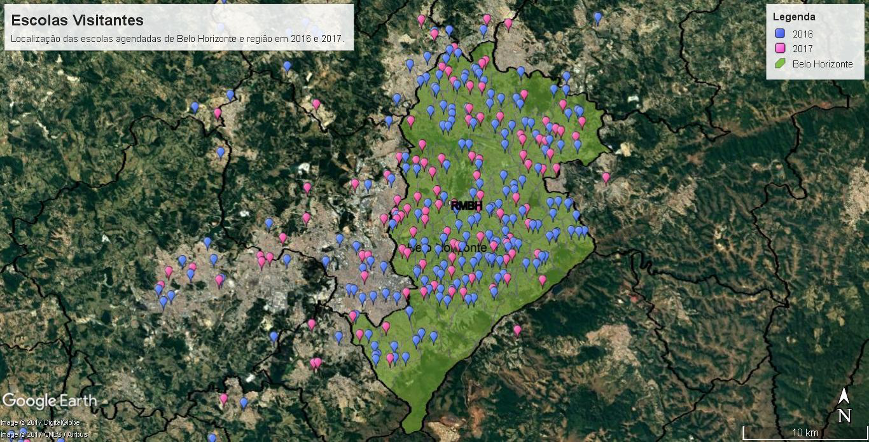

44In this perspective, the ECUFMG team sees great distinctions between the spontaneous visitors and the scheduled audience. While the spontaneous audience has a relatively homogeneous profile, the scheduled audience, composed mostly of students from public schools, presents a very diverse profile, bringing new realities into the museum. Table 2 shows the data of the museum’s scheduled audience in 2017. The data confirms a more heterogeneous profile of this audience compared to the spontaneous audience. Also, the regional representativeness of these school groups is significant (fig. 3).

45

Table 2 – Scheduled audience in ECUFMG. Photo: Elaborated by the authors, based on data from ECUFMG, 2017.

46

Figure 3 – Map of the regional representativity of schools that scheduled group visits in ECUFMG in 2016 and 2017. Photo: Elaborated by the authors, based on data from ECUFMG.

47

48The realities of the museum’s scheduled audience sometimes coincide with those from the team members, mostly extension scholarship university students. Interviewees report that when there are simultaneously public and private school visits, « two worlds intersect in the corridors of the museum ». These two « worlds » reflect two distinct socioeconomic conditions: one, a mirror of the spontaneous visitors’ profile, and another representing the first contact with this differentiated space. This second world enters a « bubble » that, perhaps, without the school, would never enter and is marked by several invisible barriers – distance, information, and belonging. This contact expands the territorial appropriation of these students, who sit on the lawn of Praça da Liberdade to eat their snacks and realize that these museums and the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG) are free of charge. By expanding the students appropriation beyond the territorial, they take ownership of a future of possibilities which they were previously unaware. Mediators show their « places » by making these children, young people, and adults connected to the EJA (Young Adult Education) identify themselves in a place they have not had a chance to dream about before. The « place that is not for our people » is, after the school visits, seen as a space for all, reinforcing ECUFMG’s mission of promoting proximity. For those who frequent it, ECUFMG is a place for dialogue, meeting diversity, ideas, and concepts while synthesizing a little of what the city is.

49

Final Considerations

50This paper investigated the role of culture and its connections with the urban space, using Espaço do Conhecimento UFMG as a case study. Culture, likewise, the city’s phenomenon, can be lived in different ways: in exchanges, in fruition, in consumption. Therefore, there is no culture or city – independent of appropriation – that does not reflect the socioeconomic conditions characteristic of that particular reality. In this sense, there is a movement, even if imperceptible in the act of experiencing the culture, whether consuming or enjoying it. At the same time, there is a social space that is circumscribed in the physical space.

51

52Therefore, the initial hypotheses were corroborated in this study: both the invisible barrier created by the non-accumulation of human and cultural capital and the breakdown of the social structure through culture can be perceived in ECUFMG. The difference is in the audience that configures this result: for spontaneous visitors, the barrier to access is given by the cultural consumer profile. For scheduled visitors, ECUFMG is an instrument of potential social change. In this way, both Bourdieu’s concept of distinction and Lefebvrian’s ideas of social emancipation are retrieved. The profile of the scheduled visitors illustrates the social hierarchy when it comes to the consumption of culture. Visits by scheduled audience represents the appropriation of the territory on the part of those a priori excluded throughout the experience of the artistic-cultural manifestation encouraged, in this case, by education.

53

54

Bibliographie

Bourdieu Pierre, 1996: Physical Space, Social Space and Habitus, Institutt for sosiologi og samfunnsgeografi, Unversitetet i Oslo.

Bourdieu Pierre, 1984: Distinction: A social critique of the judgment of the taste, London, Routledge.

Caldeira Junia M., 1998: « Praça da Liberdade: trajetória de um território urbano », IV Seminário de História da Cidade e do Urbanismo, Campinas.

Canclini Nestor G., 2001: Consumers and citizens: Globalization and multicultural conflicts, Minnesota, University of Minnesota Press.

Diniz Sibelle & Machado Ana Flávia, 2011: « Analysis of the consumption of artistic-cultural goods and services in Brazil », Journal of Cultural Economics, vol. 35, nº 1, p. 1-18.

Gil Antonio Carlos, 2008: Métodos e técnicas de pesquisa social, São Paulo, Atlas.

Haguette Teresa M. F., 2001: Metodologias qualitativas na Sociologia, São Paulo, Vozes.

Lefébvre Henri, 1991: The production of space, Oxford, Blackwell.

Lefébvre Henri, 1996: The Right to the City, Oxford, Blackwell Publishing.

Monte-mór Roberto L. M., 2005: « What is the urban in the contemporary world? », Cadernos de Saúde Pública, vol. 21, n° 3, p. 942-948.

Rubim, Antonio A. C., 2010: Políticas culturais para as cidades, Salvador, EDUFBA.

Notes

1 Espaço do Conhecimento UFMG means the Knowledge Space of Minas Gerais Federal University.

2 See : http://www.espacodoconhecimento.org.br/.

3 US$ 3.21 and US$ 16.06 respectively (US dollar values on April 5, 2017).