Trade control and protection of cultural goods in the European Union: an evolving approach?

Abstract

The dual nature of cultural goods had early prompted the European Community to introduce a legal basis for harmonized customs procedures, export and import regulations within the customs union, and later the internal market. Through an analysis of the varied terminology employed by the EU concerning cultural goods, this paper argues that the EU’s approach in this domain has undergone significant transformation over time, as evidenced by the evolution of its strategic trade control regime of cultural goods. Early regulation primarily focused on addressing internal market issues, while also endeavoring to preserve national ownership over national treasures and attending to the material aspects of cultural heritage. However, since 2015, in response to the changing security environment and international trends, the EU has expanded its perspective on strategic trade control over cultural goods to encompass a global dimension. This expansion is exemplified by the adoption of Regulation (EU) 2019/880, driven by the imperative of the prevention of looting, plundering, illicit trafficking, and the fight against terrorism financing. Furthermore, the adoption of the 2021 Council conclusions on cultural heritage protection in conflicts and crises marks a significant shift in how cultural heritage can be integrated into the EU's external actions. This evolution reflects cultural heritage’s increasing importance, both in its material and immaterial forms, across the EU’s home affairs, external actions, and internal peace and security agenda as well.

1

Introduction

2Cultural heritage—both in its material and immaterial forms—holds immense historic, artistic, and cultural value, making its protection and regulation of paramount importance nationally and internationally. Purchase and trade interest in cultural products is on the rise: the value of extra-EU exports of cultural goods increased by 22.3 % between 2017 and 2022, while extra-EU imports grew by 25 % in the same period, and growing trends can be perceived in intra-EU trade as well, despite the short setback due to COVID-19 in 2020.1 Imports and exports of cultural goods account for only a slight percentage of total trade (in the case of the EU 0.7 % of total imports and 1 % of total exports in 2022).2 However, the dual nature (as explained in Section 1.1), significant trade value, and the unique characteristics of these items, along with their associated market, justify the need to establish dedicated (strategic) trade control systems in this domain.3 This is especially critical within the context of free trade, even if it necessitates deviation from the principle of unrestricted trade.

3As an additional challenge, there has been a recurring association between the illicit selling of artifacts and other security challenges, such as organized crime and money laundering. In recent years, there has been a significant focus on the potential links with the financing of armed groups and, especially, the operation of terrorist organizations, blurring the lines between internal and external security (as elaborated in Section 2).4 This has necessitated the establishment of further regulations on their transborder flow and has made the trade control of cultural goods relevant for both home and foreign and security affairs.

4The first institutional response to establish the main principles of free trade, with the aim of liberalizing commerce globally, was the 1947 General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), the predecessor of the World Trade Organization (WTO) created in 1995. Simultaneously, the GATT included provisions for exceptions in certain specific cases, including cultural goods, to allow trade to be stopped or controlled for non-economic reasons (Articles XX and XXI, General and Security Exceptions respectively) through national measures in a restricted and clearly defined way (i.e., meeting the predefined conditions, as outlined in the chapeau).5 Article XX (f) is particularly relevant here as it provides an exception for the “protection of national treasures of artistic, historic or archaeological value.”6

5The European Union (EU) is of particular interest in this respect, as it is the only international organization with competence over trade through the adoption of legally binding regulations.7 Initially conceived as an economic integration, the European Economic Community, and later the EU, has progressively developed a substantive legal framework to address certain issues related to cultural heritage and cultural goods from various perspectives.

6However, as some authors note, “[t]he EU, in fact, does not have a cultural policy, strictly speaking.”8 On the one hand, culture, and cultural policy have traditionally been the primary competence of the Member States. Until the Maastricht Treaty, the European Communities did not possess any explicit legal basis dedicated to cultural policy per se (the trade exception for national treasures by analogy with GATT provisions will be discussed in the next section). Only Article 128 of the Treaty establishing the European Community (TEC)—now Article 167 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU)—introduced the Community’s complementary, supporting, and supplementing role in this field.9 This role is further emphasized by Article 6 of the TFEU. Additionally, it also established the obligation to “take cultural aspects into account in its action under other provisions of the Treaties”10—thus underlining the horizontal and overarching character of cultural aspects. The article also references the EU’s external activities, encouraging cooperation with third countries and other international organizations in the cultural sphere.11 Article 107 of the TFEU provides an exception for Member States regarding potential distortions of competition that may be compatible with the internal market, namely the “aid to promote culture and heritage conservation where such aid does not affect trading conditions and competition in the Union to an extent that is contrary to the common interest.”12 On the other hand, the above statement also refers to the fuzzy limits of this policy field, which has blurred boundaries with other EU-level policies (commerce, industry, development, etc.). The EU has long recognized the vital role of culture in the integration, social cohesion, solidarity, and the creation of a shared sense of European identity, as well as respect for the continent’s cultural diversity.13 From this perspective, the safeguarding and preservation of the cultural heritage of European significance, the promotion of artistic and literary creation, cultural exchanges, and, in general, the dissemination and the improvement of knowledge of the culture and history of European peoples are important to the Union.14 If we regard culture from an economic perspective, the audiovisual and creative industries, the employment potential of the cultural sector, and the closely related tourism sector, as well as the trade in cultural goods, have also been gradually placed at the forefront of the EU’s actions. The Union’s cultural policy also has an external dimension, ranging from support for international cultural or artistic exchanges to the use of intercultural dialogue as part of building lasting peace.15

7Over the time that has passed since the entry into force of the Maastricht Treaty, the EU and its Member States have faced several challenges—including globalization, subsequent enlargements, multicultural societies and the valorization of cultural diversity and intercultural dialogue, in response to the needs of cultural and creative industries—which have necessitated the enhancing of the European cultural sphere with common tools.16 The EU’s evolving position on culture is well reflected in the adoption of the first European Agenda for Culture in 2007, which has since been followed by similar strategic documents setting out guidelines in the field of culture for four-year-long terms.17 The Agenda identified cultural heritage as a priority in the EU’s work in this area.18

8A review of primary and secondary EU law shows that, depending on the objective and function of the legal instrument in question, competing and sometimes identical terms—cultural goods, cultural objects, national treasures, and cultural heritage—exist (in some cases, the same word with various meanings in different legal instruments). The aim of this paper, supported by an analysis of the related terms, is to argue the hypothesis that the EU’s motives and engagement with cultural heritage—in particular with cultural goods and the related strategic trade control regime—have evolved significantly over time. It began with a dominant protectionist trade perspective and a focus primarily on the material dimensions of cultural heritage, necessitated by the establishment of the customs union and the internal market. Progressively, it turned into a broader approach to cultural heritage protection, taking into consideration also its immaterial dimensions. This process has also entailed the growing significance of cultural heritage within both a Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP), including Common Security and Defense Policy (CSDP), and the field of internal security policy.

1. The EU legal framework for trade in cultural goods

1.1. The dual nature of cultural goods

9The dual nature of cultural goods, also referred to as cultural objects, is at the heart of understanding the exact content of the term and the respective EU legal instruments for trade. On the one hand, they possess a cultural value: cultural goods represent a given community’s interconnectedness, identity, and collective memory in a tangible, material form, apart from bearing a historic and/or artistic and/or scientific significance. On the other hand, however, cultural goods can be seen as potential commodities, subject to trade and economic activities, disposing of a monetary and transaction value. This duality reflects the complex challenges faced by the EU, possibly leading to the collision of different policies. Firstly, it touches upon cultural policy, which is regarded as a national competence and where the EU possesses only a supporting, coordinating, or supplementing role as mentioned above.19 Secondly, it includes the area of the internal market, which is a shared competence between the Member States and the EU20—as well as the customs union and common commercial policy, where the EU has exclusive competence.21

10The regulatory framework on strategic trade controls (restrictions and prohibitions) of cultural goods serves two main objectives. On the one hand, it aims to preserve cultural goods in their places of origin and retain national ownership and control over national treasures. On the other hand, it seeks to promote ethical trade practices, the prevention of illicit trafficking and, strongly connected to that, the fight against money laundering, organized crime, and the financing of terrorism. In summary, the EU’s agenda related to cultural goods prioritizes preservation and preventing their usage for unethical, unlawful and/or violent purposes. These aspects can justify certain restrictions on the free movement of cultural goods, treating them as special commodities separate from purely economic and commercial considerations. Additionally, the relevant regulations cover the rules and procedures for the restitution of stolen or unlawfully removed cultural goods and the possibilities for cooperation in investigations and prosecutions.

1.2 Rationale for trade controls on cultural goods at EU and national levels

11The setting up of uniform customs procedures and tariffs along the external borders and the elimination of frontiers between Member States within the Community have necessitated a harmonized approach to both external and internal trade regulations, including for cultural goods.

12However, the duty of Member States to protect national treasures and patrimony has justified measures limiting the common rules on import, export, and transfer.22 The Treaty of Rome of 195723—by establishing the customs union—already introduced in its Article 36 the still-in-force limitations,24 in line with the trade restrictions set by the above-mentioned GATT articles.25

13Among the justifications for which trade among Member States can be restrained, Article 36 of the TFEU—within its list of derogations–—similarly establishes the “cultural exception.”26 The Article names the protection of “national treasures possessing artistic, historic or archaeological value” as an exception to the general principle of free trade of goods and to the prohibition of quantitative restrictions on import, exports, and goods in transit between Member States. It is the competence of the national authorities to establish what they consider as national treasures in their regard, as elaborated further in Section 1.4.

14As the wording suggests, this is not a derogation of economic nature but is motivated by the aim and obligation to protect and preserve nationally significant values, whether in public or private ownership. The exception can be applied “provided they are not an arbitrary form of discrimination or a disguised restriction on trade”27—i.e., they are used proportionally and do not constitute protectionist measures that divert the application of the article from its original purpose.28 It is important to note, however, that the “trade and culture debate” is not only an internal market and customs union issue; it appears in the EU’s international trade relations and is implemented in trade agreements with third countries as well.29

15It should be noted that the Court of Justice of the European Union30—having jurisdiction over the interpretation of the Treaties—provides further guidance on applying the provisions of Article 36 on a case-law basis. In its often-cited Commission v Italy case of 1968, the Court dealt with a progressive tax system applied by Italy on exported and imported objects of artistic, historic, archaeological, or ethnographic interest. While the judgment focused primarily on the nature and role of the abolition set by Article 16 of the Treaty establishing the European Economic Community (TEEC) on charges having equivalent effect to customs, it is relevant to mention it here because it helps achieve a better understanding of the provisions of Article 36.31 In the Court’s understanding, goods (including cultural goods)—to be regarded as merchandise—“must be understood products which can be valued in money and which are capable, as such, of forming the subject of commercial transactions” and, thus, fall under the provisions of the customs union.32 Consequently, “the rules of the Common Market apply to these goods subject only to the exceptions expressly provided by the Treaty.”33 The Court excluded the applicability of Article 36 to justify the Italian tax since its aim, means and effects are incompatible with the objective of the article itself (protection of the artistic, historic, or archaeological heritage), but have “the sole effect of rendering more onerous the exportation of the products in question.”34

16In essence, Article 36 of the TFEU sets a foundation for national-level controls stemming from certain specific national interests, balancing the free movement of goods with the right of Member States to address legitimate national concerns.

17The EU-level control regime for the protection of cultural goods—based on Article 114 and Article 207 of the TFEU—is, however, also related to and refers back to the terminology used in Article 36 (national treasures). As will be elaborated in the following subsections, this latter regime includes not only the facilitation of the return of unlawfully removed cultural objects across internal borders,35 but also the harmonization of export controls at the external borders.36 An additional dimension of the EU legal framework on trade in cultural goods, adopted in 2019, applies a different focus and approach, excluding from its scope the national treasures as meant by Article 36. This latest piece of regulation—motivated much more by security and foreign affairs considerations—meant harmonizing import regulations into EU territory, existing only in an ad hoc way before (discussed in Section 2).37

1.3 Export of cultural goods: scope, thresholds, and licensing

18The Council Regulation (EEC) No 3911/92 of 9 December 1992 on the export of cultural goods established regulations for the uniform control of the export of cultural goods at the external borders, stating that, “in view of the completion of the internal market, rules on trade with third countries [were] needed for the protection of cultural goods.”38 The material scope of the Regulation—the cultural goods covered—was not explicitly defined. Instead, Annex 1 provided exhaustive taxation, listing a certain number of categories of cultural goods and setting age and/or financial thresholds, after which export “shall be subject to the presentation of an export licence.”39 The Regulation was subsequently amended, although the revisions did not fundamentally alter its approach to cultural goods. The now in-force Council Regulation (EC) No 116/2009/EC of 18 December 2008 on the export of cultural goods only slightly modified the list compared to the earlier Annex.40 The aim was to make “clear the categories of cultural goods which should be given particular protection in trade with third countries.”41

19Based on the rounds of implementation reports of the 2009 Regulation, the difficulties of a uniform reading of certain types of cultural goods are a recurring challenge. These difficulties include the classification of liturgical icons;42 ancient coins; the exhaustive or indicative nature of the list of certain types of goods in category 15.a; or the case of collections of items as opposed to single specimens in category 13.b.43 Concerning the age and financial thresholds, certain Member States uphold different opinions. Some of them (not named in the report) would prefer a lower age limit so that the Regulation covers the entirety of the goods designated as national treasures, while others would prefer a higher threshold to decrease the administrative burden of licensing a larger number of objects that are not important from a historical, scientific or artistic point of view. Similarly, in the case of financial thresholds, some would like to see an increase in limits—as there has been no revision since the adoption of the 1992 Regulation in this regard—while others suggest considering the differences among Member States’ art market selling prices.44

20The Regulation leaves unclear the relation between its scope of cultural goods and the term national treasures under Article 36, stating that it “is not intended to prejudice the definition, by Member States, of national treasures.” While the licensing system set by the Regulation is an EU-level obligation (the controls being carried out by the Member State according to the location of the object), it allows the Member States to refuse to issue an export license in the case of their “national treasures of artistic, historical or archaeological value.”45 At the same time, if an object is deemed a national treasure by the Member State but cannot be regarded as a cultural object based on the Regulation, its export is subject to the domestic law of the exporting Member State.46

21The implementation report published in 2022 sheds further light on the discrepancy that, since the Regulation does not contain a definition of cultural goods, “any object which fulfils the technical criteria of age and/or value, regardless of whether it has an actual cultural significance, may fall within the scope of the Regulation (…).”47 This suggests that cultural goods and national treasures do not coincide under this Regulation, although they intersect on several points (depending on the national legislative framework).

22The Regulation applies to all cultural goods located within the Union’s territory, regardless of their country of origin. It shall be noted that it contrasts with the approach of the later-mentioned 2014 Directive and 2019 Regulation. While both determine their scope strongly related to the provenance of the objects, the former refers to cultural objects unlawfully removed from the territory of a Member State (and classified by that Member State as national treasures),48 while the latter applies to cultural goods created or discovered outside of the customs territory of the Union.49

1.4 The evolution of the regulation concerning the return of cultural objects unlawfully removed: a tool for the restriction of the free movement of cultural objects?

23Together with the creation of the internal market and the dissolution of frontiers within the Union, the Council Directive 93/7/EEC on the return of cultural objects unlawfully removed from the territory of a Member State was adopted on 15 March 1993.50 This Directive addressed the “‘illegal” dimension of “intra-EU” export transactions, aiming to set up a protection mechanism for cultural objects qualifying as national treasures vis-à-vis the market principle of free movement of goods. Accordingly, the Directive applied to cultural objects either moved unlawfully from one Member State to another within the EU or initially exported to a non-EU country and subsequently re-imported into another EU Member State.

24Although substantially amended several times—first in 1996, then in 2001—the Directive had not proven effective in reaching its goals, resulting in only a few reported cases due to, among other reasons, its limited scope and procedural deficiencies.51 Firstly, its definition of cultural object—identical to the one provided by the 1992 and the subsequent 2009 Regulation mentioned above (categories of A1-A14 in its Annex)52—set limitations that prevented its broader applicability. As a first condition, its scope of cultural objects included those “classified, (…) among the 'national treasures possessing artistic, historic or archaeological value' under national legislation or administrative procedures within the meaning of Article 36 of the Treaty.” As an additional condition, they either had to belong to one of the categories listed in the Annex of the Directive or to be integral parts of public collections inventoried by museums, archives or libraries, or cultural objects of ecclesiastical institutions.53 A further problem was that the classification applied by the Annex was based solely on the commercial value rather than the artistic, historic, or archaeological significance. By defining a financial threshold for most categories, it deviated from the approach outlined in Article 36, which was deemed by some authors as “the original sin” of the Directive.54

25Secondly, procedural shortcomings had also hindered its effectiveness. The Directive had provided a short time (1 year) available for bringing return proceedings; and the question of the proof of burden of due care regarding the compensation of the possessor needed to be revised as well. Its focus was to provide a rapid mechanism for the return of cultural objects exported in contravention of their respective domestic rules or the rules laid down in the 1992 Council Regulation, rather than granting a tool for the fight against illicit trafficking.55 To address the deficiencies, a revision process was launched in 2009, including a public consultation ending in 2012.56 One of the findings of the Commission’s 2009 report reviewing the Directive reflected on the narrow nature of its scope, stating that the “vast majority of the Member States (…) are also in favor of amending the Annex to the Directive, either to include new categories of goods such as certain contemporary works of art, or to amend the current financial thresholds (…).”57

26The revision process eventually resulted in the adoption of the 2014/60/EU Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on May 15, 2014, which aims to remedy the shortcomings of the previous legislation by clarifying and extending the already-existing rules. “The main goal” of the review was to “enable Member States to recover any cultural object identified as a 'national treasure' that was unlawfully removed from their territories.”58 In this spirit, the new Directive already contained a more expansive definition of cultural objects—extending the scope of the Regulation—to potentially cover all objects classified as national treasures, thus deleting the Annex and the respective financial thresholds.59 In the EP’s draft resolution on the proposal, even the interchange of the term cultural object with national treasure in the title has arisen.60

27By equating the scope of the 2014 Directive (cultural objects concerned by the Directive) with the category of national treasures, it is seemingly the sole competence of Member States to define what they understand under this new piece of regulation. However, it shall be underlined that defining national treasures is not an absolute right for Member States. Firstly, the restriction cannot be applied to circumvent the rules on the free movement of goods and to hamper this freedom in an unjustified and arbitrary manner. Secondly, any measure in this regard must comply with the principle of proportionality; and thirdly, it cannot be used in violation of ownership rights. The fundamental terminological limitations of national treasures are:

-

they shall be of artistic, historic or archaeological value;

-

they shall be important from the perspective of the Member State;

-

they shall be state-owned (public patrimony), or the patrimony of churches or religious communities, or be of other objects which bear national importance owned by non-public entities.61

28Linking the definition of cultural objects with the one of national treasures has required Member States to define their own understanding of national treasures as well. However, it is beyond the scope of the present article to give an overview of the different solutions and to compare the scope for national implementation.

29Aiming to foster cooperation and mutual trust among Member States and to facilitate the return of cultural objects further, this new legislation has also introduced increased administrative cooperation, enhancing it by the compulsory use of common tools, such as consulting and exchanging information through a module specifically customized for cultural objects within the Internal Market Information System (IMI).62 As an additional goal, the contribution to the EU’s objectives on prevention and combat against trafficking is also mentioned,63 reflecting the Union’s intensifying mobilization in this regard. Compared to its predecessor, the Directive sets extended time limits for checking the nature of the cultural object found, now set at six months. It also extends the limit for instituting return proceedings, setting it at three years from the date on which the central authority of the requesting Member State became aware of the location of the object and the identity of its possessor, but not exceeding 30 years from the date of the unlawful removal.64 The Directive also decided about the payment of compensation, to be coupled with an obligation on the possessor to prove the exercise of due care and attention, specifying the circumstances to be considered as well.65

2. Cultural goods and cultural heritage in the context of CFSP and Home Affairs

2.1 The evolving role of cultural heritage in the EU’s CFSP

30The term cultural heritage received an EU-level definition only in 2014, in parallel with the EU’s aim to increase culture’s strategic importance in its external relations. Gradually, cultural heritage has been integrated into the EU’s external policy toolkit, including the CFSP and the CSDP. Since 2016, the protection of culture and cultural values, along with efforts to combat illicit trafficking in cultural goods beyond its borders, have increasingly come to the forefront of the EU’s foreign policy agenda, and have gradually gained a security and defense policy relevance as well.66

31This process was primarily induced by the widespread terrorist attacks on cultural heritage sites. These attacks received extensive media coverage, starting with incidents in Mali (Timbuktu, 2012) carried out by al Qaeda-affiliated terrorist groups, and subsequently in Iraq and Syria since 2014 by ISIL (Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant), exemplified by events in Mosul or Palmyra, in 2015.67 The recognition of the motives behind and the short- and longer-term effects of cultural heritage destruction and looting further underscored the importance of addressing these issues.68

32While providing a detailed and comprehensive analysis of the evolving place of culture and cultural heritage in CFSP lies beyond the scope of this paper, this subsection aims to focus specifically on the main trends and the terminology used, particularly within the context of CSDP efforts.

33During her address to the United Nations (UN) General Assembly in 2017, Federica Mogherini—former High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy and Vice-President of the European Commission—outlined her priorities regarding the cultural heritage protection within CFSP efforts. These priorities, subsequently reflected in later EU/EEAS (European External Action Service) instruments, encompassed:

-

the inclusion of cultural heritage protection in military and civilian missions’ mandates;

-

the provision of financial support and technical assistance for restoration projects;

34fight against illicit trafficking of cultural goods.69

35The Foreign Affairs Council’s Conclusions on the establishment of a civilian CSDP compact in 2018 also highlighted the need to take into account cultural heritage protection and preservation aspects in tackling security challenges.70 In 2022, the compact was supplemented with a mini-concept dedicated to challenges linked to cultural heritage protection and preservation in order to identify possible areas and lines for enhancing civilian CSDP efforts in this domain.71

36The adoption of the EEAS’s ‘Concept on Cultural Heritage in Conflicts and Crises in 2021, followed by subsequent Council Conclusions, clearly meant a landmark point in the process. It stands as the first comprehensive document to address heritage protection within CFSP. It set the frames of the EU’s actions and priorities on this subject, pointing out a substantial change in how cultural heritage can be incorporated into the EU’s external action, contributing significantly to its strategic approach to the humanitarian-peace-development nexus.72 Its adoption can be seen as a culmination of a securitization trend and growing awareness at an international level regarding cultural heritage protection,73 reflecting on recent years’ terrorist attacks on heritage sites, together with an increasing commitment of the international community to handle related issues in the frame of maintaining international peace and security.

37The 2021 conclusions adopted by the Foreign Affairs Council use the definition of cultural heritage introduced in the 2014 Council conclusions mentioned in Section 1, with slight supplements.74 The concept further clarifies what is meant under tangible and intangible forms of cultural heritage, implying their inseparable nature, using the terminology of the 1972 UNESCO World Heritage Convention and the 2003 UNESCO Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage, respectively.75

38The Concept, applying an integrated approach, recognizes the need to consider cultural heritage “throughout all phases of conflicts and crises – in prevention, crisis response, stabilisation and longer-term peacebuilding and recovery process with a cross-cutting approach,” setting guidelines for its integration in political and diplomatic engagement, crisis management, peace and development etc.76 Results so far include, amongst others, the integration of cultural heritage protection aspects into certain (civilian) CSDP missions (especially EUAM Iraq, EUMM Georgia) and the support of specific projects in conflict zones or post-conflict areas (for example Acting to preserve Ukrainian Heritage from 2022, Rehabilitation of Cultural Heritage and Safeguarding of Ancient Manuscripts of Mali (2014-2016 and 2017-2021)).77

2.2 The reframing of illicit trafficking of cultural goods

39The EU has long been dealing with different dimensions of the phenomenon of trafficking in cultural goods, including the theft of cultural goods from public or private collections, the looting of archaeological sites, and the displacement of artifacts due to armed conflicts.78 However, “[a] shift [can be perceived] in framing since 2000 of how trafficking in cultural goods sourced to the Middle East or North Africa is discussed publicly”—turning the discourse more and more over the potential linkages to different security issues, including the funding of armed non-state actors.79

40In 2008 and 2011, the Justice and Home Affairs Council adopted its conclusions on preventing and combating crime against cultural goods.80 A 2011 report by the European Commission and the research center of the University of Poitiers (CECOJI) recognizes the fact that “trafficking in cultural goods is among the biggest criminal trades, estimated by some to be the third or fourth largest.”81 According to a later impact assessment conducted by the European Commission, 80–90% of antique sales globally are of objects of illicit origin.82 Although estimations on the size of the black market of cultural goods vary widely, several experts have called attention to the fact that this issue shall not be approached primarily from an economic perspective, but rather from its destructive effects on our heritage.83 In addition, the specificities of the market (including the high value of pieces, the potential to use them as a tool for money laundering, or to store them for a long time before putting them on the market etc.)84 along with other factors (such as the growth of online trading activities) make these goods especially vulnerable.

41The above-mentioned trend became particularly apparent after 2015, when the prevention of and fight against illicit trafficking became strongly interlinked with efforts to combat the financing of terrorism in EU discourse and policy (both in the area of home affairs and CSDP).85 This shift was also motivated by the activities of ISIL: the organization generated funds through sales of cultural objects and taxes levied on diggers of archaeological remains. Some sources suggested that trafficking in cultural goods meant the second largest revenue for the terrorist group, while others claimed that it meant only a “marginal source of financing” for them.86 In its 2016 report, for example, the Centre for the Analysis of Terrorism estimated around 30 million USD in revenue for 2015, meaning around 1 percent of the organization’s total revenue.87

42The EU Security Agenda adopted in 2015 already encourages measures related to the illicit trade in cultural goods as a potential element of its stepping up against terrorism financing.88 The 2016 action plan to intensify the fight against terrorism proposed launching a legislative proposal specifically aimed at combating illicit trafficking in cultural goods (resulting in the adoption of the below-mentioned 2019 Regulation).89

43The in-depth study published by the European Commission and ECORYS in 2019 aimed to provide a better understanding of challenges and tools for combatting illicit trade in cultural goods, relying on the definition proposed by the 2009 Regulation regarding the scope of cultural goods.90 As argued by several authors previously, the study is on the opinion that looting and trafficking of cultural property is first and foremost a criminal activity not directly related to armed conflicts.91 There is only scattered evidence (for example on Taliban in Afghanistan, or ISIL in Libya, Iraq, and Syria) available so far on the effective contribution of it to financing armed nonstate actors, especially terrorist organizations. However, the usage of this linkage in public discourse seems beneficial to be a mobilizing force and to give political weight to the issue, moving the combat against illicit trafficking higher on the political agenda of national and international security.92

44The EU Security Union Strategy, adopted in July 2020, called for measures to be taken both in the internal market in order to improve the online and offline traceability of cultural goods and in cooperation with source countries. One of the main actions foreseen in the Commission’s EU Strategy to Tackle Organised Crime 2021-2025 was the adoption of a dedicated action plan in 2022. On December 13, 2022, the European Commission eventually presented the EU Action Plan against trafficking in cultural goods. Following a similar reasoning as the 2019 Regulation, discussed in the next subsection, the Action Plan “uses a broad definition of cultural goods that includes artefacts of a historical, artistic, scientific, or ethnological interest, as mentioned in the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property of 1970.”93

45The document also encourages the incorporation of cultural heritage protection—including the combat against illicit trafficking—into the EU’s external actions. It places particular emphasis on conflict- and crisis-stricken countries. As part of this effort, the deployment of specialists in missions and operations, the inclusion of cultural goods trafficking issues in dedicated CSDP training modules on cultural heritage in conflicts and crises, and continued support to Ukraine in the field of cultural heritage protection are on the EU’s agenda.94

2.3 The establishment of an EU-level regulation on the import of cultural goods: evidence of a shift in mindset?

46The newest element of the trade regulation of cultural objects, adopted in 2019, reflects on the increasing role of illicit trafficking outside the Union’s borders and its presumed relation with money laundering and financing terrorism and, in parallel, the EU’s efforts to integrate the protection of cultural goods into its fight against terrorist financing. The integration of cultural goods into the EU’s strategic trade control regime and its relationship to international peace and security considerations (the potential end-use of the objects) is strikingly manifested.

47Regulation 2019/880 of the European Parliament and of the Council establishes an EU-level regulation on the import of cultural goods, replacing the fragmented and diverse national-level regulations. The proposal for this new piece of EU regulation was made in 2017, initiated by the 2016 Action Plan to strengthen the fight against terrorist financing.95 However, it is also in line with the series of resolutions adopted by the UN Security Council in relation to Iraq and Syria (especially Resolutions 2199 (2015) and 2347 (2017))96, which indicate a strengthened cooperation with the UN organ to respond to related international crimes and implement binding norms.97

48The stated objective of the Regulation is to prevent the pillage, unlawful appropriation, and illicit trade of cultural goods by prohibiting the introduction of unlawfully exported cultural goods from third countries, especially those affected by armed conflict, particularly where it may contribute to the terrorists financing. In a broader perspective, according to some authors, it aims to become the “regional component of UNESCO’s global system to combat the illicit trafficking of cultural property.”98

49The adoption of the 2019 Regulation “does not simply introduce various new elements in regulating the import of cultural property, but heralds a new age for EU cultural property legislation.”99 Although it was adopted in the framework of the common commercial policy, similar to the 2009 Regulation, its approach represents a significant shift. While the 2009 Regulation focused on the protection and uniform control of cultural goods on EU territory in external trade relations regarding exports, emanating from the necessities of the internal market, this new piece of legislation is much more driven by security considerations and the responsibility to protect the cultural heritage of third countries.

50The adoption of the Regulation was not without precedent. At the EU level, import rules regarding illegally removed objects were formerly limited to restrictive measures on trade in cultural goods first from Iraq by Council Regulation (EC) No 1210/2003 of 7 July 2003 concerning certain specific restrictions on economic and financial relations with Iraq and repealing Regulation (EC) No 2465/96. In the case of Syria, the restrictive measures adopted by the EU in 2011 after the breakout of the civil war were extended in 2013 to include aspects of cultural heritage protection by Council Regulation (EU) No 1332/2013 of 13 December 2013 amending Regulation (EU) No 36/2012 concerning restrictive measures in view of the situation in Syria. These provisions were drafted in strong connection with the efforts to fight against terrorism and organized crime. As the two regulations were born as part of the respective sanctions regimes, their primary goal was not to provide an additional tool for cultural heritage protection as a whole but rather to include temporary measures as part of the economic pressure exerted on these specific countries.100 Both regulations included in their Annex taxation regarding the categories of cultural goods subject to restriction, similar to the 2009 Regulation.

51The 2019 Regulation introduces a different understanding of cultural goods compared to that of the 2009 Regulation and the 2014 Directive, which carry forward the terminology of their predecessor legislative acts, focusing on the harmonization processes among national legislations within the internal market. In contrast, the 2019 Regulation considers cultural goods as “any item which is of importance for archaeology, prehistory, history, literature, art or science as listed in the Annex.”101 Due to the Regulation’s external trade orientation and security policy approach, the EU opted to refer here to international conventions to which most of its Member States are signatories and whose definitions are similarly applied by third countries as well. Thus, the list provided by the Annex principally relies on the definitions set by the legal instruments of UNESCO and UNIDROIT.102 It follows the cultural property–cultural object definitions offered by the 1970 UNESCO Convention and the 1995 UNIDROIT Convention respectively and applies a similar cut-off date (1972) to the one of the UNESCO Convention.103 Consequently, the 2019 Regulation limits its scope to cultural goods created or discovered outside of the EU104—delimiting it from the category of national treasures already regulated by the above-mentioned legal instruments.105

52Using a differentiation in the rules, the Annex of the 2019 Regulation determines a special age and monetary value threshold for certain categories listed in parts B and C. For items falling under these categories, the importation to the territory of the Union requires the provision of an import license (B) or an importer statement (C) to the customs authorities.

53Certain authors criticize the usage of terms from the organizations mentioned above combined with the thresholds applied by the Regulation for several reasons. These include the inconsistency with the terminology used in similar (the above-mentioned) EU legal acts, and the lack of their specificity, which makes it complicated to categorize certain objects. In addition, the fact that certain objects—potentially the most vulnerable to illicit trafficking (ex. ancient coins)—may fall outside the scope of the Regulation could hinder the effectiveness of its implementation.106

54The Regulation emphasizes the place of cultural goods in the broader framework of cultural heritage—as tangible, movable forms of cultural identity and collective memory—pointing out the strong interconnections between its material and immaterial dimensions. While we cannot find any reference in the 2009 Regulation, the 2014 Directive uses the term once (referring to the aim to protect “cultural heritage of European significance”).107 The 2019 Regulation embraces the term in a much broader way, referring to it as “humanity’s cultural heritage” and as “one of the basic elements of civilization.” This shift is also reflected in the approach to cultural goods, which takes into consideration their symbolic significance (and that of their loss) to local communities, beyond their purely financial value. As part of the EU’s efforts in the field of fighting against terrorism financing, the regulation “should take into account regional and local characteristics of peoples and territories, rather than the market value of cultural goods.”108 It also recognizes the role of the pillaging of cultural goods in wider security challenges (forced homogenization, maintenance of shadow economies, money laundering, financing of organized crime and terrorist groups).

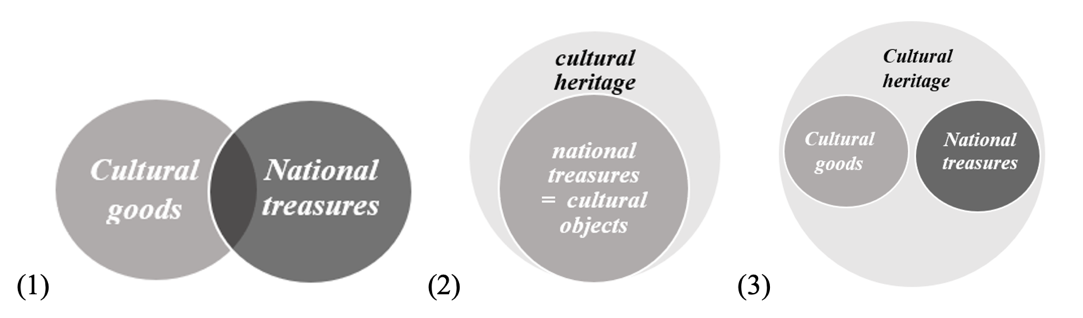

55The relationship between the terms cultural heritage, cultural goods (or cultural objects), and national treasures, as applied by the above-presented legal instruments is visualized in Figure 1. In brief, three approaches regarding the understanding of cultural goods at the EU and national levels can be discerned using the differentiation outlined in the 2011 report of the European Commission Directorate-General Home Affairs and CECOJI.

56The 2014 Directive follows the logic of the first approach, corresponding to number (1) of Figure 1 below, which considers cultural goods as objects belonging to a state’s heritage, necessitating protection to remain within or be repatriated to the state's territory. Under this perspective, the determination of heritage value and criteria is left to the discretion of the state. Some of these cultural goods receive specific treatment due to their nature or their particular exposition to certain risks.

57In contrast, the 2009 and 2019 Regulations rather adopt the second approach, corresponding to number (2) and (3) of Figure 1 below, which entail a broader understanding of cultural goods, extending beyond national heritage in its strict sense and encompassing more than just goods of high value that are (already) part of national treasures.

Figure Relationship of the terms cultural heritage, cultural goods/cultural objects and national treasures under (1) Council Regulation (EC) No 116/2009, (2) Directive 2014/60/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council and (3) Regulation (EU) 2019/880 of the European Parliament and of the Council (ed. by the author)

58The third approach, not examined in this present paper, extends even further, including “objects and works of art even when they are not recognised as part of the cultural heritage.” This approach is usually reflected by rules on supervising transactions involving works of art (e.g., online sales) and criminal law. 109

Results of the analysis and concluding remarks

59The meaning of the terms related to cultural goods used by the EU differ according to the exact aim and scope of the legal act concerned—to better and more effectively serve its purposes—especially as regards the nexus of the terms cultural goods/cultural objects and national treasures. “Depending on the goal pursued, the concept of cultural goods may be more or less selective, at times relating to national treasures to be preserved and transmitted to future generations and at others to any work of art, etc., when the interests of the purchaser and so of the consumer are at stake.”110

60As some authors point out, the use of the “cultural goods” concept (compared to that of cultural property used by international conventions of UNESCO) can be explained by the fact that while the EU has limited competence in the field of culture, “trade in works of art involves ‘goods’ that trigger the application of the provisions on the free movement of goods within the EU and the rules of the common commercial policy in relation to third countries.”111 Although linked to common commercial policy in nature, the paper aimed to point out that the implementation of the strategic trade control regime of cultural goods can serve as instruments to enhance cultural (e.g., preserving and promoting national and European cultural heritage) as well as CFSP (including CSDP) or home affairs policy goals (e.g., fight against money laundering, organized crime and terrorism financing, contribution to peacebuilding), the two latter putting a more and more significant focus on this issue recent years.

61With an extending regulatory framework embracing import restrictions after the adoption of the 2019 Regulation, the EU’s strategic trade control regime has gained an actual global dimension, prioritizing the protection of cultural heritage out of EU territory as well. Its adoption shall be seen as part of a wider global trend. Induced by the violent and widely broadcasted attacks by terrorist groups against cultural heritage first in Mali (2012), and later in Iraq and Syria, the international community, including the EU, has strengthened its commitment and increased its mobilization to protect cultural goods, heritage sites and intangible heritage—using the comprehensive term of cultural heritage—in conflict-stricken environments from physical destruction as well as looting and plundering.

62While evidence is scarce on the relationship between illicit trafficking of cultural goods and terrorism, leveraging this linkage in public discourse serves for the EU to elevate the issue on the political agenda for international security, well reflected by the 2021 EEAS Concept and subsequent Council conclusions. Within the increasing relevance of culture in its external actions, the EU has paid special attention to cultural heritage protection out of its borders gradually linking it with home affairs and CFSP-CSDP objectives, policy fields that have become committed to taking actions relating to the heritage-security nexus.

Notes

1 “Culture statistics – international trade in cultural goods. Statistics explained,” Eurostat, accessed October 2023, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Culture_statistics_-_international_trade_in_cultural_goods#Cultural_trade_in_2022_at_EU_and_national_level.

2 Eurostat, “Culture statistics”.

3 For a more detailed analysis of the nature of EU strategic trade control and the place of cultural goods in it, see: Quentin Michel, “EU strategic trade controls and sanctions: are we talking about the same thing?,” Journal of Strategic Trade Control, Issue 1, (2023).

4 Brigitte Slot, Olga Batura, Illicit Trade in Cultural Goods in Europe: Characteristics, Criminal Justice Responses and an Analysis of the Applicability of Technologies in the Combat against the Trade, LU: Publications Office of the European Union, 2019, p. 12, https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2766/183649.

5 Quentin Michel, Veronica Vella and Lia Caponetti, Introduction to International Strategic Trade Control Regimes (Liege: European Studies Unit - University of Liege, 2021), pp. 9-12, https://www.esu.ulg.ac.be/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/ISTCR-2021.pdf.

6 General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, 1947, Article XX.

7 Michel, Vella and Caponetti, Introduction to International Strategic Trade Control Regimes.

8 They propose instead different terms such as “European policy of culture” to describe the related legal norms and institutional mechanisms. See: Oriane Calligaro and Antonios Vlassis, “La Politique Européenne de La Culture: Entre Paradigme Économique et Rhétorique de l’exception,” Politique Européenne N° 56, no. 2 (16 November 2017), pp. 8–28, https://doi.org/10.3917/poeu.056.0008.

9 While initially, relevant incentive measures were subject to unanimity, the Lisbon Treaty extended the ordinary legislative procedure in this regard.

10 Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (Consolidated version [2016/C 202/01]), Article 167.

11 Especially the Council of Europe – see the joint implementation of European Heritage Days since 1991, for example.

12 Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, Article 107.3 (d).

13 Treaty on European Union (Consolidated version [2016/C 202/01]), Preamble and Article 3.

14 See Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, Article 167.

15 Yudhishthir Raj Isar, “Culture in EU external relations’: an idea whose time has come?,” International Journal of Cultural Policy, Vol. 21, no. 4, (2015), pp. 494-508.

16 Ágnes Környei, “Kulturális és audiovizuális politika,” in Az Europai Unió szakpolitikai rendszere, ed. Tibor Ördögh (Budapest: Ludovika Egyetemi Kiadó, 2022), pp. 409–24.

17 Marta Suarez Gonzalez, “Restitution of Cultural Heritage in the European Directives: Towards an Enlargement of the Concept “Cultural Goods”’, Art, Antiquity and Law, Vol. 23, no. 1 (2018), pp. 1–28.

18 Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions towards an integrated approach to cultural heritage for Europe, COM(2014) 477 final. The 2007 Agenda says, “culture should be regarded as a set of distinctive spiritual and material traits that characterise a society and social group. It embraces literature and arts as well as ways of life, value systems, traditions and beliefs,” “[…] it can refer to the fine arts, including a variety of works of art, cultural goods and services. 'culture' also has an anthropological meaning. It is the basis for a symbolic world of meanings, beliefs, values, traditions which are expressed in language, art, religion and myths. As such, it plays a fundamental role in human development and in the complex fabric of the identities and habits of individuals and communities.”

19 Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, Article 6, and Article 167.

20 Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, Article 4, and Articles 26-27

21 Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, Article 3, Articles 28-32, and Article 207.

22 2021/C 100/03. Guide on Articles 34-36 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), Commission notice, 23.3.2021., 7.1.3.

23 Treaty establishing the European Economic Community, succeeded by the Treaty Establishing the European Community from 1993 and the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union from 2009.

24 Formerly Article 30 of the TEC, Article 36 of the TEEC.

25 Quentin Michel, Veronica Vella, and Lia Caponetti, Introduction to International Strategic Trade Control Regimes, pp. 107-111.

26 Other justifications under the same Article include: public morality, public policy or public security; the protection of health and life of humans, animals or plants; the protection of industrial and commercial property.

27 Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, Art. 36

28 Commission notice Guide on Articles 34-36 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, Official Journal of the European Union (C 100) of March 23, 2021.

29 Lilian Richieri Hanania, “Trade, Culture and the European Union Cultural Exception,” International Journal of Cultural Policy, Vol. 25, no. 5 (29 July 2019), pp. 568–8.

30 Until 2009: European Court of Justice.

31 Article 16 of the Treaty establishing the European Economic Community: “Member States shall abolish as between themselves, not later than at the end of the first stage, the customs duties on exportation and charges with equivalent effect.”

32 Judgment of the Court of 10 December 1968, Commission of the European Communities v Italian Republic. Case 7/68, pp. 428-429.

33 Judgment of the Court of 10 December 1968, p. 429.

34 Judgment of the Court of 10 December 1968, p. 429.

35 Council Directive 93/7/EEC of 15 March 1993 on the return of cultural objects unlawfully removed from the territory of a Member State; replaced by: Directive 2014/60/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15 May 2014 on the return of cultural objects unlawfully removed from the territory of a Member State and amending Regulation (EU) No 1024/2012, Official Journal of the European Union (L 159) of May 28, 2014.

36 Council Regulation (EEC) No 3911/92 of 9 December 1992 on the export of cultural goods; replaced by: Council Regulation (EC) No 116/2009 of 18 December 2008 on the export of cultural goods, Official Journal of the European Union (L 39) of February 10, 2009.

37 Regulation (EU) 2019/880 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 April 2019 on the introduction and the import of cultural goods, Official Journal of the European Union (L 151) of June 7, 2019.

38 Council Regulation (EEC) No 3911/92 of 9 December 1992 on the export of cultural goods, Official Journal of the European Union (L 395) of December 31, 1992.

39 Council Regulation (EEC) No 3911/92, Annex.

40 Adding the category of “Watercolours, gouaches and pastels executed entirely by hand on any material” which “are more than 50 years old and do not belong to their originators.”

41 Council Regulation (EC) No 116/2009 of 18 December 2008 on the export of cultural goods (Codified version), Official Journal of the European Union (L 39) of February 10, 2009, Preamble.

42 In the case of liturgical icons, the clarification by Regulation (EU) 2019/880 is expected to settle the issue (as it states that “liturgical icons and statues, even free-standing, are to be considered as cultural goods belonging to” the category of “elements of artistic or historical monuments or archaeological sites which have been dismembered”).

43 Report from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council and the European Economic and Social Committee on the implementation of Council Regulation (EC) No 116/2009 of 18 December 2008 on the export of cultural goods 1 January 2014 - 31 December 2017, COM(2019) 429 final, September 26, 2019; Report from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council and the European Economic and Social Committee on the implementation of Council Regulation (EC) No 116/2009 of 18 December 2008 on the export of cultural goods 1 January 2018 to 31 December 2020, COM(2022) 424 final, August 26, 2022.

44 Report from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council and the European Economic and Social Committee, COM(2022) 424 final.

45 Council Regulation (EC) No 116/2009 on the export of cultural goods, Article 2.

46 Council Regulation (EC) No 116/2009 on the export of cultural goods, Article 2.

47 Report from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council and the European Economic and Social Committee, COM(2022) 424 final.

48 Directive 2014/60/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council, Art. 2 (1).

49 Regulation (EU) 2019/880 of the European Parliament and of the Council, Art.1.2.

50 Council Directive 93/7/EEC of 15 March 1993 on the return of cultural objects unlawfully removed from the territory of a Member State.

51 Draft European Parliament legislative resolution on the proposal for a directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on the return of cultural objects unlawfully removed from the territory of a Member State (recast), COM(2013)0311 – C7‑0147/2013 – 2013/0162(COD), January 28, 2014.

52 But applying different financial thresholds.

53 The original proposal limited the definition of cultural objects classified as national treasures only to the ones listed in the Annex. See: Proposal for a Council Directive on the return of cultural objects unlawfully removed from the territory of a Member State, (92/C 53/15) (COM (91) 447 final), January 20, 1992.

54 Anna Frankiewicz-Bodynek and Piotr Stec, “Defining ‘National Treasures’ in the European Union. Is the Sky Really the Limit?,” Santander Art and Culture Law Review, Vol. 5, no. 2 (2019), pp. 77–94.

55 Suarez Gonzalez, “Restitution of Cultural Heritage in the European Directives”.

56 Maciej Górka, “Directive 2014/60: A New Legal Framework for Ensuring the Return of Cultural Objects within the European Union,” Santander Art and Culture Law Review, no. 2 (2016), pp. 27–34.

57 Report from the Commission to the Council, the European Parliament and the European Economic and Social Committee - Third Report on the application of Council Directive 93/7/EEC on the return of cultural objects unlawfully removed from the territory of a Member State, COM/2009/0408 final, October 31, 2023.

58 Answer given by Mr Tajani on behalf of the Commission (22 April 2013) to the Commission by Diogo Feio (PPE), E-002077/13, February 25, 2013, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=OJ:C:2013:372E:FULL&qid=1695733225714.

59 Directive 2014/60/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council, Article 2 (1). Cultural object “means an object which is classified or defined by a Member State (…) as being among the ‘national treasures possessing artistic, historic or archaeological value’ under national legislation or administrative procedures within the meaning of Article 36 TFEU.”

60 Draft European Parliament legislative resolution, COM(2013)0311 – C7‑0147/2013 – 2013/0162(COD).

61 Frankiewicz-Bodynek and Stec, “Defining ‘National Treasures’ in the European Union.”

62 Directive 2014/60/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council, Article 7.

63 Directive 2014/60/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council, Preamble, paragraphs (16) and (17).

64 Directive 2014/60/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council, Article 8.

65 Directive 2014/60/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council, Preamble, and Article 10.

66 See: Joint communication to the European Parliament and the Council - Towards an EU strategy for international cultural relations, JOIN(2016) 29 final, June 8, 2016.

67 A wide range of literature is dealing with this issue, see for example: Alessandra Russo, and Serena Giusti, “The securitisation of cultural heritage,” International Journal of Cultural Policy, Vol. 25, no. 7 (2019), pp. 843-857; Marie Elisabeth Berg Christensen, “The cross-sectoral linkage between cultural heritage and security: how cultural heritage has developed as a security issue?,” International Journal of Heritage Studies, Vol. 28, no. 5 (2022), pp. 651-663; Anna Puskás, “The securitization of cultural heritage protection in international political discussion through the example of attacks of ISIL/Daesh,” International Scientific Journal Security & Future, Vol. 3, no. 3 (2019), pp. 96-100.

68 See for example: Helga Turku, The Destruction of Cultural Property as a Weapon of War: ISIS in Syria and Iraq (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018); Thomas G. Weiss and Nina Connelly, “Protecting Cultural Heritage in War Zones”, Third World Quarterly, Vol. 40, no. 1 (2 January 2019), pp. 1–17.

69 “Speech by F. Mogherini at UN General Assembly, on Protecting Cultural Heritage”, Cultural Relations Platform, posted September 21, 2017, https://www.cultureinexternalrelations.eu/2017/09/21/speech-by-f-mogherini-at-un-general-assembly-on-protecting-cultural-heritage/.

70 Conclusions of the Council and of the Representatives of the Governments of the Member States, meeting within the Council, on the establishment of a Civilian CSDP Compact, 14305/18, November 19, 2018.

71 Civilian CSDP Compact - Mini-concept on possible civilian CSDP efforts to address security challenges linked to the preservation and protection of cultural heritage, 12499/22, September 15, 2022.

72 Kristin Hausler, “The EU Approach to Cultural Heritage in Conflict and Crisis: An Elephant in the Room?”, Santander Art and Culture Law Review, Vol. 7, no. 2 (31 December 2021), pp. 193–202.

73 For a more detailed analysis, see: Anna Puskás, “Culture Matters: European International Organizations’ Policies for Cultural Property Protection in Conflict and Crisis Situations”, National Security Review, no. 2 (2021).

74 These supplements include the listing of galleries among public and private bodies managing and conserving collections; and the leaving out of the clarification of what is meant under digital cultural heritage as regards its origin (“born digital and digitised”).

75 Concept on Cultural heritage in conflicts and crises. A component for peace and security in European Union’s external action, European Union European External Action Service, 9962/21, June 18, 2021.

76 Concept on Cultural heritage in conflicts and crises. A component for peace and security in European Union’s external action, p. 5.

77 For more details see: 2023 Report on the progress in the implementation of the “Concept on Cultural Heritage in conflicts and crises: A component for peace and security in European Union’s external action” and the dedicated Council Conclusions, 11054/23, June 26, 2023; 2022 Report on the progress in the implementation of the “Concept on Cultural Heritage in conflicts and crises. A component for peace and security in European Union’s external action” and the dedicated Council Conclusions, 12398/22, September 14, 2022.

78 “Combatting Trafficking in Cultural Goods”, Culture and Creativity, European Commission, accessed October 2023, https://culture.ec.europa.eu/cultural-heritage/cultural-heritage-in-eu-policies/protection-against-illicit-trafficking.

79 Neil Brodie et al., “Why There Is Still an Illicit Trade in Cultural Objects and What We Can Do About It”, Journal of Field Archaeology, Vol. 47, no. 2 (17 February 2022), pp. 117–30.

80 Council Conclusions of 28 November 2008 on preventing and combating illicit trafficking in cultural goods, 14224/2/08 REV 2 CRIMORG 166 ENFOPOL 191.

81 CECOJI-CNRS and European Commission, Study on Preventing and Fighting Illicit Trafficking in Cultural Goods in the European Union. Final Report, (Brussels, 2011), https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/ca56cfac-ad6b-45ab-b940-e1a7fa4458db.

82 The assessment is referenced by: Parliament resolution of 17 January 2019 on cross-border restitution claims of works of art and cultural goods looted in armed conflicts and wars, P8_TA(2019)0037.

83 European Commission - Directorate General for Education, Youth, Sport and Culture., Trafficking Culture., and ECORYS., Illicit Trade in Cultural Goods in Europe: Characteristics, Criminal Justice Responses and an Analysis of the Applicability of Technologies in the Combat against the Trade: Final Report, Luxemburg: Publication Office of the European Union, 2019, pp. 78-79.

84 Financial Action Task Force, Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing in the Art and Antiquities Market, Paris, February 2023, https://www.fatf-gafi.org/content/dam/fatf-gafi/reports/Money-Laundering-Terrorist-Financing-Art-Antiquities-Market.pdf.coredownload.pdf

85 See on this also the subsequent European Parliament resolutions: European Parliament resolution of 11 June 2015 on Syria: situation in Palmyra and the case of Mazen Darwish (2015/2732(RSP)), P8_TA(2015)0229; European Parliament resolution of 30 April 2015 on the destruction of cultural sites perpetrated by ISIS/Da’esh (2015/2649(RSP)), P8_TA(2015)0179; European Parliament resolution of 17 January 2019 on cross-border restitution claims of works of art and cultural goods looted in armed conflicts and wars (2017/2023(INI)), P8_TA(2019)0037.

86 Justine Drennan, “The Black-Market Battleground”, Foreign Policy, October 17, 2014, https://foreignpolicy.com/2014/10/17/the-black-market-battleground/.

87 Laurence Bindner, and Gabriel Poirot, “ISIS Financing in 2015”, Center for the Analysis of Terrorism, May 2016, https://cat-int.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/ISIS-Financing-2015-Report.pdf, pp. 19-20.

88 Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions - The European Agenda on Security, COM/2015/0185 final, April 28, 2015.

89 Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council on an Action Plan for strengthening the fight against terrorist financing, COM/2016/050 final, February 2, 2016.

90 European Commission, Illicit Trade in Cultural Goods in Europe.

91 See for example: Hausler, “The EU Approach to Cultural Heritage in Conflict and Crisis”; Pierre Losson, “Does the International Trafficking of Cultural Heritage Really Fuel Military Conflicts?”, Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, Vol. 40, no. 6, (2017); Kate Fitz Gibbon, “Art Imports to EU Threatened by Draconian Regulation”, Cultural Property News, December 29, 2018, https://culturalpropertynews.org/art-imports-to-eu-threatened-by-draconian-regulation/.

92 European Commission, Illicit Trade in Cultural Goods in Europe, 112-115.

93 Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions on the EU Action Plan against Trafficking in Cultural Goods, COM/2022/800 final, December 13, 2022.

94 Communication from the Commission on the EU Action Plan against Trafficking in Cultural Goods, COM/2022/800 final.

95 Communication from the Commission on an Action Plan for strengthening the fight against terrorist financing, COM/2016/050 final.

96 UNSC Resolution 2199, Threats to international peace and security caused by terrorist acts, adopted by the Security Council at its 7379th meeting, on February 12, 2015, S/RES/2199 (2015); UNSC Resolution 2347, Maintenance of international peace and security, adopted by the Security Council at its 7907th meeting, on March 24, 2017, S/RES/2347 (2017).

97 Michele Graziadei and Barbara Pasa, “The Single European Market and Cultural Heritage: The Protection of National Treasures in Europe”, in Cultural Heritage in the European Union, ed. Andrzej Jakubowski, Kristin Hausler, and Francesca Fiorentini (Brill: Nijhoff, 2019), pp 79–112.

98 Hanna Schreiber, “Regulation (EU) 2019/880 and the 1970 UNESCO Convention – A Note on the Interplay between the EU and UNESCO Import Regimes”, Santander Art and Culture Law Review, Vol. 7, no. 2 (31 December 2021), pp. 173–82.

99 Tamás Szabados, “The EU Regulation on the Import of Cultural Goods: A Paradigm Shift in EU Cultural Property Legislation?”, CYELP, Vol. 18, no. 1 (2022), p.19.

100 Szabados, “The EU Regulation on the Import of Cultural Goods”, pp. 1-23. On the difference of the two terms, see: Michel, “EU strategic trade controls and sanctions”.

101 Regulation (EU) 2019/880 of the European Parliament and of the Council, Article 2.1

102 Explanatory Memorandum to COM(2019)429 - Implementation of Council Regulation (EC) No 116/2009 of December 2008 on the export of cultural goods 1 January 2014 - 31 December 2017, September 26, 2019.

103 Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property, UNESCO, 1970; Convention on Stolen or Illegally Exported Cultural Objects, UNIDROIT, 1995.

104 Regulation (EU) 2019/880 of the European Parliament and of the Council, Article 1.2.

105 Regulation (EU) 2019/880 of the European Parliament and of the Council, Preamble paragraph (5).

106 Anna M. De Jong, “The Cultural Goods Import Regime of Regulation (EU) 2019/880: Four Potential Pitfalls”, Santander Art and Culture Law Review, Vol. 7, no. 2 (31 December 2021), pp. 31–50.

107 It should be noted that the EU’s understanding of cultural heritage was first defined by the Council only in 2014. In developing a new strategic approach in this field, the Council regarded cultural heritage as “resources inherited from the past in all forms and aspects – tangible, intangible and digital (born digital and digitized), including monuments, sites, landscapes, skills, practices, knowledge and expressions of human creativity, as well as collections conserved and managed by public and private bodies such as museums, libraries and archives. It originates from the interaction between people and places through time and it is constantly evolving.” Source: Council conclusions of 21 May 2014 on cultural heritage as a strategic resource for a sustainable Europe, 2014/C 183/08.

109 CECOJI-CNRS and European Commission, Study on Preventing and Fighting Illicit Trafficking in Cultural Goods in the European Union, pp. 69-76.

110 CECOJI-CNRS and European Commission, Study on Preventing and Fighting Illicit Trafficking in Cultural Goods in the European Union, p. 19.

111 Szabados, “The EU Regulation on the Import of Cultural Goods”, p. 16.