- Home

- Special Issue, Vol. 2

- Building a culture of responsibility: education for disarmament and non-proliferation

View(s): 413 (5 ULiège)

Download(s): 43 (2 ULiège)

Building a culture of responsibility: education for disarmament and non-proliferation

Attached document(s)

original pdf fileAbstract

Controlling the development, utilization, or transfer of dual-use technologies underlying non-conventional weaponry has become a significant issue from a disarmament and non-proliferation perspective. However, evidence suggests that stakeholder communities often lack awareness of technology transfer risks and their responsibilities in preventing or mitigating their consequences.

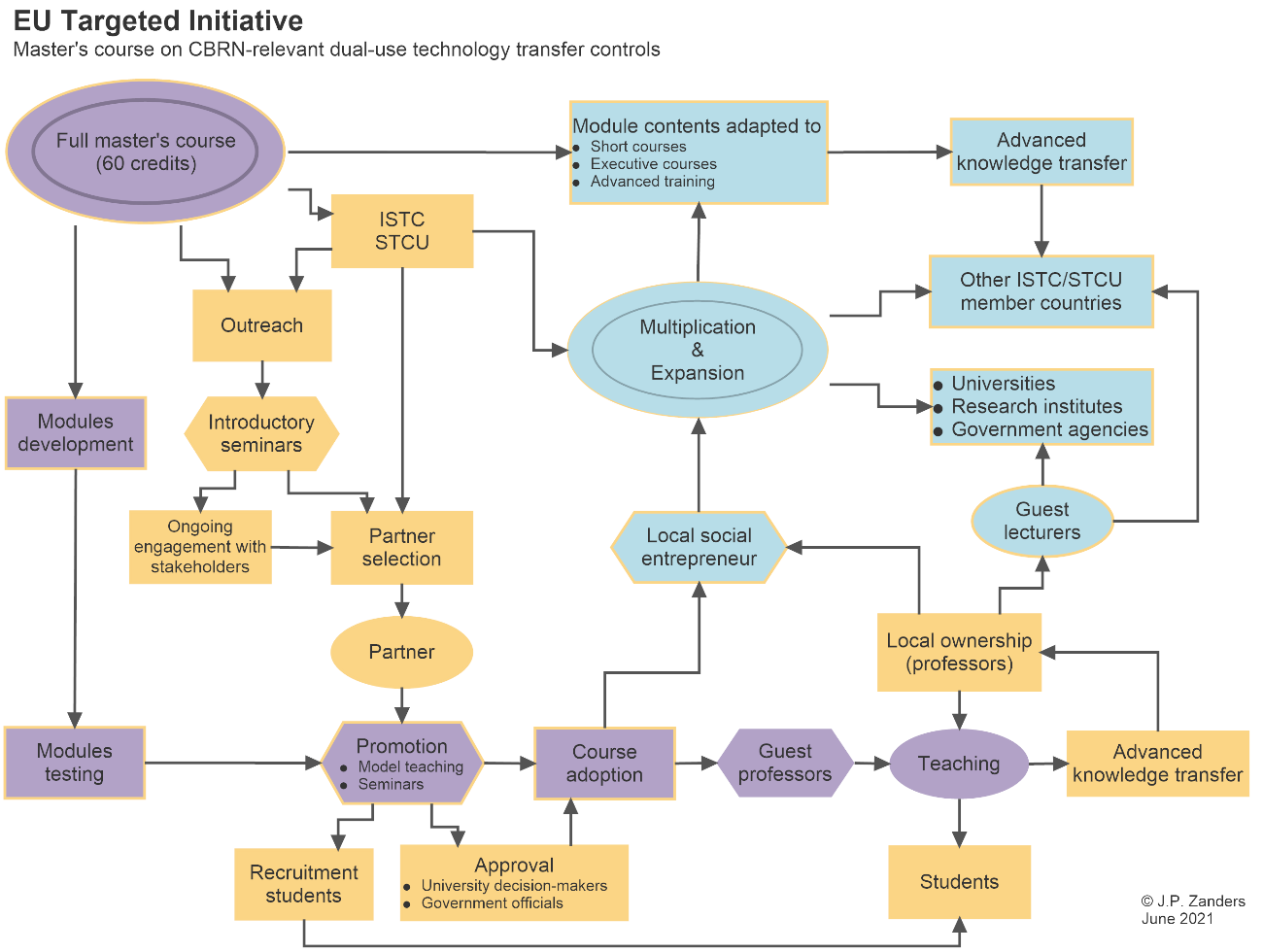

This article examines the case of the master’s course on chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear (CBRN)-relevant dual-use technology transfer controls developed within the framework of the European Union-funded Targeted Initiatives on “Export Controls of Dual-Use Materials and Technologies” as part of efforts to address these challenges. The paper outlines the process of developing and implementing this modular course, successfully implemented in several former Soviet republics in Central Asia and Southeast Europe.

Emphasizing the preference for education over more traditional training approaches, the article discusses how the course aims to enhance awareness and foster responsible behavior among stakeholders. In addition to assisting academic institutions in setting up the courses and advancing knowledge among professors, significant effort was invested in engaging decision-makers and various stakeholder communities to broaden the educational initiative’s foundations. Under the organizing theme of building a culture of responsibility, these interactions proved to have significant educational value and contributed to the core ambitions of local ownership and sustainability.

In conclusion, the article argues that sustained educational efforts and collaborative initiatives are essential for addressing challenges posed by dual-use technology transfers and contributing to global security and non-proliferation efforts.

Table of content

Introduction

1Controlling the development, utilization, or transfer of dual-use technologies underlying non-conventional weaponry has emerged as a significant issue in the realm of disarmament and non-proliferation.1 It is pertinent to acknowledge that the control of chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear (CBRN) weapons has evolved beyond being solely the purview of states. Historically, particularly in the earlier stages of atomic weapons development, states predominantly held control over such technologies. However, contemporary realities reflect a notable shift. A lot of scientific research, technology development, and production occurs in universities and private companies. Technology diffusion through trade, staff turnover and migration, widening education abroad, and expanding virtual project collaboration mean that sub-state, international, and transnational actors are crucial to today’s technology transfer processes. Governments have increasingly shifted responsibilities for the safe transfer of potential dual-use technologies to those agents. Reports from meetings of state parties or review conferences of weapon control treaties emphasize the responsibilities of natural or legal persons to prevent unauthorized access to certain types of technology, including through the adoption of workplace security and safety measures. The recommendations in such reports are an excellent motivator for substantive educational engagement with key stakeholder communities.2

2This article outlines the design and development of a university master’s course focused on CBRN-relevant technology transfers and its implementation in different national, cultural, and educational contexts.3 Central to this educational endeavor is the ownership by local project partners, such as universities, research institutes, or their representatives, and the long-term sustainability of the course, which became the primary objectives of the educational project. Despite challenges posed by the COVID-19 global pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, adaptation led to different experiences, including enhanced networking among various academic and scientific institutions. The establishment of collaborative initiatives reinforced ownership and sustainability, significantly advancing the ultimate objective of promoting governance of dual-use technology transfers under the organizing theme of building a culture of responsibility.4

3Underlying the idea of a university master’s course was a choice for education over traditional training and capacity-building activities. However, education involves more than merely offering courses at academic institutions and preparing lecturers for the task. It entailed preparing the ground through outreach to key stakeholder groups in academia, research institutions, industry, and commerce, as well as promotional activities supporting student enrolment. Moreover, it required continuous engagement with decision-makers at levels of university faculties and rectorates, as well as relevant government agencies. Ultimately, these activities and engagements proved educational in their own right and prepared the ground for sustainability and local ownership, two primary objectives of this educational project.

4The paper starts with a brief overview of the origin of the Targeted Initiatives, the EU-funded programs aimed at addressing the challenges surrounding the control of dual-use technologies transfer related to CBRN. It also situates the education work package within the Targeted Initiatives. Subsequent sections delve into the education work package in more detail, exploring the elements contributing to the preference for an educational method over a more traditional training program. The article then discusses the project initiation and the reasons for adopting a modular approach to the course design. The final part considers how networking and local capacity-building contribute to local ownership and sustainability before closing with some conclusions.

The EU Targeted Initiatives

5In 2017, the EU initiated a program to design and implement new ways of enhancing export controls governing the transfer of dual-use technologies underlying the development and production of CBRN weapons. Building on achievements and insights from the EU Partner to Partner (P2P) Export Control Programme—which is the EU outreach export control program, started in 2004 and renamed P2P in 20165—the newly launched Targeted Initiatives on “Export Controls of Dual-Use Materials and Technologies” sought to achieve two primary objectives.6 Firstly, it aimed to engage the academic community in the CBRN knowledge area. Secondly, it aimed to encourage partner countries to implement and enforce effective export controls. The European Commission funded the program in support of the EU’s Global Strategy (2016) and Strategy Against the Proliferation of Weapons of Mass Destruction (2003).7

6The European Commission entrusted the International Science and Technology Centre (ISTC) in Astana, Kazakhstan, and the Kyiv-based Science and Technology Centre in Ukraine (STCU) with implementing the Targeted Initiatives.8 ISTC engages Central Asian and Southeast European countries (primarily Armenia, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan), whereas STCU serves Georgia, Ukraine, Azerbaijan, and Moldova (GUAM).9

7An international coalition of states, including the United States (US) and the EU, set up both science centers in the mid-1990s, inspired by the goals of the US Comprehensive Threat Reduction Programme initiated in 1991.10 During the Cold War, the Soviet Union developed and produced large chemical, biological, and nuclear arsenals in a sprawling military-industrial complex. After its breakup, the weapon depots, training sites, and research, development, and production installations became scattered over many fledgling states. Moreover, the centralized command-and-control system overseeing infrastructure and activities fell apart. From their inception, the science centers prioritized engaging with engineers, scientists, and technicians who had been involved in the former Soviet weapon programs. Concerns arose as these highly educated and trained personnel lost their social status, privileges, and income, raising fears that they might seek to sell their CBRN-related knowledge, skills, and expertise to foreign countries. Today, the ISTC and STCU continue to provide, among other things, financial assistance and facilitate collaborative civilian technical research and training to new generations of engineers, scientists, and technicians.

8The EU Targeted Initiatives thus fit into the core mission of both science centers. Although the ISTC and the STCU operated under separate contracts with the European Commission, both programs ran concurrently. The ISTC initiated its program in October 2017, while the STCU commenced in February 2018. Both projects ended in December 2023. While there were some variations in implementation, mainly due to regional specificities and specific needs and expectations of participating institutes, the core set-up of the work packages was common to all project participants.

9Initially, the Targeted Initiatives envisaged five work packages, one of which did not materialize. The four that proceeded addressed: establishing a network of scientists (WP2); developing a master’s course on export controls (WP3); providing PhD grants (WP4); and conducting outreach to industry (WP5).11

10For each work package, a person with proven relevant expertise was responsible for setting specific objectives within the Targeted Initiatives’ overall framework, developing appropriate methodologies, and deploying activities to achieve the goals. A general coordinator monitored progress in each work package and ensured that the work package leads remained appraised of initiatives and results in the other project components. Additionally, the overall coordinator also encouraged the work package leads to identify and exploit possible synergies among them.

11This article will exclusively focus on WP3, delving into the development and implementation of the master's course on export controls. Before discussing the details of the course, the rationale behind preferring education over more traditional training approaches will be examined below.

The preference for education

12The master’s course developed under the Targeted Initiatives seeks to enhance the general understanding of the security concerns about dual-use technologies. Its objectives include enabling participants to understand how these technologies might affect their professional roles and individual responsibilities. Moreover, the course intends to empower them to identify and address issues associated with dual-use technologies.

13

14While various international organizations, government agencies, academic and scientific institutions, and civil society organizations undertake some education in disarmament and non-proliferation, most of those initiatives primarily focus on building professional capacity, raising awareness, or assisting with designing, developing and implementing legal and regulatory measures in line with international obligations concerning CBRN weapons. Despite these efforts, the observation persists that academics, scientists, students, and stakeholders in private industry and commerce are unfamiliar with international legal instruments and national laws and regulations governing their activities. Consequently, they may lack insight into how their activities with dual-use potential could—inadvertently—contribute to weapon development and the proliferation of technological capacities to countries or other entities seeking proscribed weapons.

15The principal cause for such lack of awareness is the absence of formal instruction in present or future risks about scientific research or technology development beyond those relating directly to workplace activities. Their knowledge about international legal instruments, such as disarmament treaties or non-proliferation arrangements, or national laws and regulations implementing them may range between rudimentary and non-existent. Even if some level of risk consciousness is present, representatives from institutions, companies, or even government agencies may be hesitant to acknowledge any connection between their work and weapon development. This knowledge deficit about broader governance frameworks extends to ethical debates on the social implications of researching, developing, manufacturing, and trading certain technologies.12 It affects how new proposals are assessed and monitored for risk or activity results evaluated. Methodological approaches and organization of capacity-building activities may explain the persistence of such lack of awareness among key stakeholder communities:

-

Most courses are short-term, often limited to a few days or a week. Even if specific courses make up part of a broader or longer-term package, there is limited follow-up with course participants to assess how much they have internalized the new information or practices.

-

Capacity-building courses are not part of continuous education. This has three significant implications.

-

-

First, their organization may be a one-off event or repeated annually. If multiple events occur in a single year, their reiteration may target other states, regions, linguistic communities, or institutions.

-

Second, a capacity-building course cannot follow a participant’s progression in knowledge, expertise, and experience, meaning that the opportunities for that person to fully assimilate the value of the course content concerning current or future activities may be limited.

-

Third, the more specific the course contents, the more challenging a course participant may find their application to different contexts.

-

-

Many courses follow a train-the-trainer model in the expectation that course participants will convey the new information or practices to a broader audience. Usually, the course organizer will not follow up with any quality assessment of how or to whom course participants transfer their newly acquired knowledge and expertise. In addition, the extent to which course participants can engage with peers outside their immediate work environment remains unclear. While the train-the-trainer approach seeks multiplication effects, there is no guarantee of follow-on activities taking place or, if they do, of educational quality in those sessions.

-

There is no guarantee that participants are the most appropriate to take the course. In many instances, governments or institutions will nominate, upon invitation, an individual to follow the course based on criteria beyond the control of the course organizer.

-

Sponsors and implementors of capacity-building courses cannot assess in advance the likelihood that participants may influence practices in an institution or company, nor do they have formal indicators or relevant information to evaluate transformation in workplace practices.

16In 2017, the Advisory Board on Education and Outreach (ABEO) of the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) set out to evaluate educational methodologies and recommend specific approaches in support of the OPCW’s objectives, namely eliminating and precluding the use of chemical weapons and preventing their re-emergence. The ABEO comprises 15 persons from different countries on all continents with expertise in education, treaty implementation, and engagement with stakeholder communities. In February 2018, the OPCW published its Report on the Role of Education and Outreach in Preventing the Re-emergence of Chemical Weapons.13 The present author then chaired the ABEO.

17One of the key ABEO recommendations holds that target audiences should discover the issues for themselves, how they affect their work, and, consequently, why they should seize them. Answering those questions represents a significant educational process in its own right. Furthermore, educational exercises have shown that each one of the professional categories may have specific awareness of issues relevant to their work field. Still, people may not realize that colleagues and partners from other disciplines can face similar challenges in different contexts. Consequently, besides being multi-disciplinary, the course also has to be cross-disciplinary.

18As a general conceptual framework, the insights and recommendations in the report inspired and guided the development and implementation of the education work package. Regular briefings to the ABEO members on progress and experiences with the Targeted Initiatives also yielded valuable comments, suggestions, and insights.To summarize, making academics, scientists, students, and stakeholders in private industry and commerce conversant with international legal instruments and national laws and regulations on dual-use activities and technologies that could contribute to developing CBRN weapons is but a first necessary step in an educational process. It is more impactful when those stakeholder communities transpose the formal rules into practical guidance for staff. Besides participation in capacity-building courses, the latter goal requires institutional backing to implement such guidance in daily work activities. As part of the educational undertaking, the capacity-building project must engage key decision-makers in universities, research institutes, companies, and government agencies to let them discover why certain routine practices prevent misuse or inadvertent transfers of science and technology. This multi-stakeholdership supporting the master’s course explains the necessity for framing and promoting the organizing theme “building a culture of responsibility”.

Education work package: the master’s course on export controls

19The initial assignment under the education work package was straightforward: designing and implementing a master’s course on CBRN-relevant dual-use export controls. The projected running time was two years. Despite the possibility of extensions, the time frame was short to design a course from scratch and incorporate it into a university curriculum. Work began in February 2018, and the Taras Shevchenko National University (TSNU) in Kyiv started teaching the course in October 2019.

20In these sixteen months, several other, more refined goals emerged or became better articulated. Two of the most important ones were sustainability and the transfer of ownership to the local partner. Both objectives were intertwined yet demanded separate sets of preparatory actions.

21Sustainability implies that the partnering university would continue to teach the course even after project sponsorship and financial support ends. The contracts the academic institutions participating in the Targeted Initiatives signed with the ISTC or STCU reflected that undertaking. More importantly, the objective required the development and execution of several sustainability strategies. On the one hand, the new course had to attract the interest of sufficient students. Therefore, actively reaching out to the student body with a view to their enrolment in the future course became an early and urgent necessity. In the months preceding the course launch, the local project partner at the TSNU held information sessions. They also organized briefings with the overall coordinator of the Targeted Initiatives and the education work package lead and set up sample lectures open to students and academic staff. On the other hand, they also arranged meetings with university decision-makers on the faculty and rectorate levels. These appointments allowed the overall coordinator and work package lead to explain the need for a master’s course on dual-use technology transfer controls and highlight the course’s relevancy for the participating university in the short and longer terms. Their invitation as speakers at internal seminars for faculty members, academics, and lecturers enabled them to communicate with faculty and university-wide audiences to build broader institutional receptibility for the proposed master’s course. Most of these activities took place in parallel with the development of the curriculum. They also aided with the course design by contributing to a clearer understanding of the educational needs and practices.

22To help launch the master’s course at the TSNU, a student sponsorship initiative covering university enrolment fees supported the initial recruitment drive. However, it was time-limited from the outset. The money allocation per student was halved in the second year of teaching. The initiative enabled the local project partner to broaden student recruitment and meet one of the university’s minimum requirements for continuing the course.

23Transfer of ownership is crucial for achieving sustainability, but it involves different actions. One aspect was investment in building capacity. Intensive lecture sessions for professors prepared them for teaching in the new master’s course.

24A second facet was the identification of potential key stakeholders in the master’s course among the scientific community, industry, and concerned government agencies. It also included facilitating interactions between the local project partner and those stakeholders. Several strategic reasons called for these types of activities. First, expressing stakeholder interest in the course because of the direct benefits graduate students would bring those stakeholders is a powerful argument to present to university decision-makers. Second, direct interactions with the different actor communities become a primary source of information about future job opportunities, student internships, and trainee positions. Having this type of job market intelligence and being able to offer positions for hands-on training make for a strong student recruitment argument. Third, some of those stakeholders might become sources for future funding via subsidies or grants. Finally, members from assorted stakeholder communities could also become expert lecturers in the master’s course, thus offering students first-hand knowledge, experience, and expertise.

25Two additional strategic levers emerged after the Targeted Initiatives entered their third year: building national and international academic networks and setting up a research base. Student numbers were an important criterion for starting and sustaining the CBRN-relevant dual-use technology export control course. At the TSNU, the person in charge of organizing the course decided from the outset that the lectures would be open to students from other faculties and academic institutions. This choice proved fortuitous when the COVID-19 pandemic started shutting down social and economic life in February 2020, leading to European border closures.

26Ukraine closed its borders in the middle of March, and the final set of lectures on export controls had to be delivered virtually. The pandemic also posed an immediate threat to continuing the educational initiative in the 2020-2021 academic year and beyond. The solution came in the form of extra-mural classes open to anybody in Ukraine registering for the virtual lectures. Still, the initiative required coordination with other Ukrainian academic institutions and promotion of the course among their students. The process of clarifying the process and specific objectives of extra-mural teaching during the late spring and early summer of 2020, together with the outreach activities by the TSNU person in charge, was the de facto origin of the networking objective in the education work package of the Targeted Initiatives. Development of its strategic concept continued throughout 2020 and into 2023.

27The Targeted Initiatives ended in December 2023. Six target countries—Kazakhstan, Kyrgyz Republic, and Tajikistan in Central Asia and Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine in Southeast Europe—adopted one or more modules of the master’s course developed under the Targeted Initiatives. In all instances, national education authorities accredited the programs.

Designing and developing the master’s course

28Whereas the Targeted Initiatives foresaw from the outset the introduction of a master’s course on CBRN-relevant export controls, they identified few parameters beyond a general statement that it would offer the package to universities for inclusion in their curriculum. It raised multiple questions. Who would implement the course, or more precisely, which university faculties may be involved? Who would be the target audiences: students taking their first university degree, students with prior degrees seeking to specialize in non-proliferation and export controls, or professionals required to enhance or update their knowledge? Which issue areas would the master’s course cover? What prior knowledge about CBRN weapons and their underlying technologies would the target audience possess or require? A final question, which eventually became the point of departure for the course design, concerned the contents.

A mind-mapping exercise

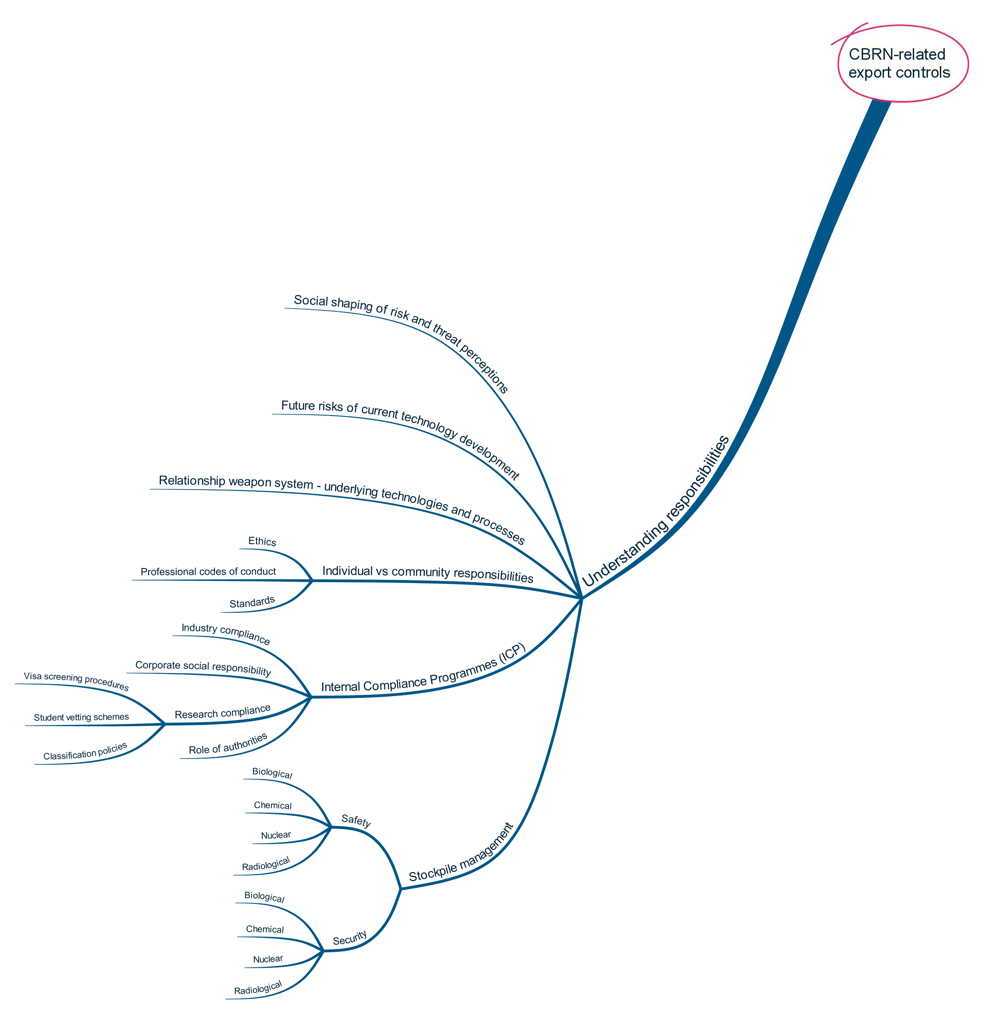

29The course design began with a mind-mapping exercise aimed at thoroughly identifying all potential issues to be covered in the master’s course. These issues were then grouped into broad topics. Within each topic, content-related hierarchies were established, ranging from top-level considerations to issue details. Additionally, the exercise built linkages between the different branches and sub-branches where relevant. The mind map eventually comprised eight main branches organized into two parts: topics and strategies.

30Topics contained five branches:

-

-

-

Basic knowledge covers the CBRN weapon spectrum and introduces core concepts in disarmament, arms control, and non-proliferation.

-

Dual-use technologies introduce the concepts of technology and processes related to technology innovation. It addresses how technology relates to disarmament, arms control, and non-proliferation and inserts the notions of single, dual-use, and tangible and intangible technologies.

-

International control regimes cover the range of legal instruments affecting CBRN weapon technologies and their transfers from global and regional treaties to international sanctions and embargoes, as well as plurilateral arrangements to prevent their proliferation.

-

Understanding responsibilities addresses risk and threat perceptions and the responsibilities different categories of actors each have in preventing or mitigating such risks and threats. The branch also covers the relationship between the weapon systems and their underlying technologies and innovation processes. (See Figure 1 for a visual representation of the organizational structure of the mind map branch ‘Understanding responsibilities’, which illustrates branches of topics and strategies).

-

-

Figure The mind map branch “Understanding responsibilities”

31Strategies comprised three branches:

-

-

-

Educational strategy: identifies the central parameters for the course grouped along four core questions: what, why, how, and who?

-

Transfer controls: lists the various actors and stakeholders involved in regulating and implementing dual-use technology transfers.

-

Economic relationships: concerns the different partners in domestic and international technology transfers and the various transfer patterns.

-

-

32Given the intention to deploy the master’s course in Central Asia and the GUAM countries, the anticipated varied professional and cultural backgrounds of course participants posed considerable challenges from the perspective of educational methodology.

33Some of the early workshops organized by the ISTC and STCU in 2018 yielded a clearer vision of potential users, i.e., the institutions planning to introduce the course. Moreover, the discussions revealed that those potential users envisaged different course offerings. These included short introductory sessions, one-week short courses, and two-week intensive executive courses for professionals, government functionaries, and research institutes working with or on technologies with potential dual-use characteristics that might contribute to CBRN weapon development.

34Discussions with university representatives pointed to multiple possible configurations for the master’s course, most of which involved integrating the proposed lectures into existing curricula rather than establishing a standalone course of study leading to a specialized master’s degree. They also had elective packages in mind.

35Learning of these different contexts led to a modular course design approach. Several self-contained learning units could meet the various requests for course configuration on varying levels of expertise.

The modular construction of the master’s course

36The master’s course on CBRN export controls concerning dual-use materials and intangible technologies was conceived as a fully credited program.14 Structurally, it consists of modules, which, while part of the bigger whole, are also self-contained teaching units. As such, a local project partner can integrate one or more modules in an existing master’s course, or the modules can be deployed independently or combined according to the educational needs of specific target groups, such as professionals or government officials. A module comprises ten to twelve academic lectures of two hours each.

37The master’s course developed under the Targeted Initiatives contains nine modules divided into three segments, namely two Introductory Modules (IM), four Substantive Modules (SM), and three Seminar Modules (SE).

The introductory modules

38The original and primary purpose of the introductory modules was to enable anyone interested in advancing their knowledge in weapons control, technology transfer, and export controls to participate in the course. By spring 2018, the preparatory workshops organized by the ISTC and STCU had already revealed that knowledge about transfer controls, their foundations in international and domestic law, and the respective responsibilities of assorted stakeholders in academia and scientific communities, commerce and industry, and government was far from universal. Moreover, the interest in hosting the course by representatives from different academic disciplines or types of institutions suggested the need for more widespread, shared knowledge. The ambition to open the export control course to students from other faculties reinforced the latter point. Two introductory modules were organized as follows:

-

-

IM1: CBRN basic knowledge and concepts introduce course participants to the basic concepts relating to CBRN weapons and their control; the concept of dual-use technologies and the challenges these pose from a policy perspective; and the formal, multilateral treaties and other arrangements set up to prevent their misuse.

-

IM2: Frameworks, instruments and responsibilities aims to provide a holistic overview of frameworks and mechanisms relevant to CBRN export controls, their respective objectives, and areas of operation. Those instruments also engender responsibilities for different categories of actors. This module introduces those responsibilities and links them to broader societal and policy contexts.

-

39In June 2019, the master’s course went through an intensive, two-week test run in Astana, Kazakhstan and yielded important additional insights for arranging the basic modules. Specifically, prior elementary knowledge about the technologies concerned, the regulatory environment, or transfer processes could not be assumed. Moreover, methodologies to search pertinent information (e.g. via the Internet) were rudimentary. For instance, they lacked insight into how to set up structured searches and verify the returned information. Several participants also conducted searches on a mobile phone, unaware that the screen’s small size impeded complex search operations.15 These experiences were informative on how to set up active learning sessions while teaching the modules.

The substantive modules

40Four substantive modules were organized as follows:

-

-

SM1: Threats, risks, and their mitigation offers an in-depth analysis of the various ways in which threats and risks related to CBRN materials and technologies manifest. It explores the different mechanisms through which technology transfers may deliberately or accidentally occur. Additionally, it establishes connections between threats and risks with various frameworks and instruments designed to counter them. As an introduction, it also delineates the roles played by multiple national implementers and categories of national and international actors.

-

SM2: Transfer controls (international level) addresses the international regulatory level. The historical analysis introduces students to the origins of export control regulations and also places their evolution in the context of international developments. The module discusses the various international instruments and their respective approaches under which a state must prevent proliferation activities.

-

SM3: Transfer controls (national level) shifts the focus to the national regulatory level. It educates students on the process of transposing international obligations into national legislative and regulatory frameworks, and discusses the options available to legislators and regulators. Finally, it emphasizes the importance of engaging and educating key stakeholder communities on their specific contributions or responsibilities regarding preventing CBRN proliferation.

-

SM4: Promoting responsible behavior addresses advances in science and technology and their potential contribution to CBRN proliferation. Participants learn how they, in their professional capacity or as individuals, must build situational awareness and contribute to raising awareness, education, and outreach within their professional contexts. Such contribution can come in many forms, including the design of such activities, the promotion of ethical standards and professional codes, or the actual running of such activities. Moreover, it emphasizes the value of fostering networks between government agencies and stakeholder communities, as well as among various stakeholder groups.

-

The seminar modules

41The three proposed seminar modules create the space for applying active learning methods through exercises and case studies relating to the topics covered in the introductory and substantive modules. While envisaged as self-contained units to promote student assimilation of the theoretical and conceptual parts, the lecturer has significant leeway over integrating the practical lectures.

42The course outline proposed the following themes for the seminars:

-

-

SE1 reinforces the objectives of SM1 and SM2. It could engage students in two ways. First, they can relate to the issues they believe affect them most and identify the actors with whom they should interact to prevent proliferation. Through group discussions, they can explore how similar issues present themselves to different actors and discover whether another person’s insights and experiences may be relevant to one’s context. Second, students can be familiarized with particular national and international tools (such as internet resources).

-

In SE2 (suggested to follow SM3), course participants could be presented with specific scenarios they must resolve using the national regulatory frameworks and institutions. Discussions could, for instance, lead to identifying gaps or opportunities for amelioration, thus leading to policy options and their justification.

-

SE3 (suggested to follow SM4) can combine two objectives. First, students can be exposed to (experience) various educational strategies and acquire practical insights into their design and goals. A second part of the seminar can be dedicated to the interactive review of the whole course and preparation of the dissertation, etc.

-

43As noted earlier, the need for a multi- and cross-disciplinary approach in education was one of the crucial findings in the ABEO report of February 2018. The organization of the modules reflected this need. The TSNU integrated the two introductory and four substantive modules in a two-year master’s program called “Economic Security of Entrepreneurship”. Guest professors taught the modules for the first time. Their primary areas of expertise were CBRN armament and disarmament dynamics (IM1 and SM1), international law and export controls (IM2 and SM2), domestic implementation of international legal obligations (SM3), and governance of science and technology (SM4). Besides the students, the local professors slated to take over the modules in the next academic year also followed the lectures. Among them were economists, political scientists, legal experts, and nuclear physicists. This combination of guest professors and aspiring local academic staff highlighted the multi-disciplinary mix of a course on transfers involving CBRN-relevant dual-use technologies.

44In February 2021, the Technical University of Moldova organized a one-week intensive course on non-proliferation education (repeated in 2022). Local professors had expertise in nuclear physics and technology transfers but also wanted to enhance their knowledge about issues and challenges in the chemical and biological fields. However, student participants reflected the rich disciplinary diversity the course attracted. Technical University of Moldova master’s students from the Schools of Micro-nanoelectronics and Biomedical Engineering and fourth-year undergraduate students from the School of Biomedical Engineering attended the lectures. In addition to the students mentioned above from the Technical University of Moldova, master students from various universities were also in attendance, including participants from the State University of Moldova (law and physics) and the University of Medicine and Pharmacy (general medicine).16 The Caucasus International University in Tbilisi, Georgia, inserted elements from the different modules in an existing master’s course on international security and non-proliferation and appointed the TI’s overall coordinator as a visiting professor.17

45The table below summarizes the main disciplines and issue areas relevant to CBRN-relevant dual-use technology transfers.

|

Multi- and interdisciplinary design (Main subject areas involved) |

|

|

Law |

Economics |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Political and social sciences |

Sciences and engineering |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Etc. |

|

|

46Considering that not all faculties or even academic institutions have all relevant expertise in-house, educational and professional networks may offer the simplest and most cost-effective solution to building a well-rounded program supporting disarmament and non-proliferation.

Building networks for sustainability

47As noted, sustainability and local ownership are two critical goals of the Targeted Initiatives’ master’s course on export controls. Since 2019, the master’s course has been deployed in various configurations, including intensive short courses (up to one week) and executive courses (two weeks) for students, professors, and professionals. Moreover, the six introductory substantive modules also got integrated into a two-year master’s program in Ukraine, and participating institutions in the other target countries also adopted two or more of the modules in existing master’s programs depending on specific needs. Finally, the TSNU in Kyiv transferred the course to a different academic unit in the university, allowing the teaching of the introductory modules already in the final bachelor’s year. The flexibility in the modular design of the master’s course contributed to the twin goals of sustainability and ownership. Throughout the process, two aspects of sustainability emerged: (a) increasing advanced knowledge capacity among professors involved in the projects and (b) building multi- and interdisciplinary networks among professors across different faculties within a single university, among different universities within the same country, and potentially among universities across different countries participating in the Targeted Initiatives. This evolution generated new requirements and challenges to be addressed.

48For instance, the Targeted Initiatives allowed the training of professors on both introductory and advanced levels. However, given the intensity of these courses, the training was limited to a select number of professors because of the cost of organizing local or regional in-person sessions or the constraints of virtual teaching. The COVID crisis and the war in Ukraine also restricted the options. Nonetheless, these resource limitations, coupled with unforeseeable events, pointed to the broader risk of losing resource investment whenever teaching staff move to different positions, institutions, or countries. Additionally, factors like employee attrition (e.g. retirement) could further affect the long-term viability of export control education.

49Networks inside and among universities, research institutes, and professional organizations can vest institutional interest in the educational project. Similarly, setting up a research base involving multiple stakeholders will support the teaching component by producing graduates who can compensate for attrition over the longer term or help expand the educational and research program. Eventual participation in international networks may contribute to international recognition of expertise in the target countries and lead to invitations to participate in multinational research programs.

50Contrary to the master’s program, the Targeted Initiatives did not lay out a concrete networking work program because local project partners are responsible for building local ownership and sustainability. It became necessary that one or more of the local project partners assumed the role of social entrepreneur to seek out and nurture relationships with stakeholder communities and other academic and research institutions. To assist the process, the present author developed a note outlining a common framework for local project partners to discuss collaboration and establish a shared research platform dedicated to CBRN-relevant dual-use technology transfer controls.18 This research platform will stimulate further thinking by initiative takers in different institutions about possible goals and implementation stages for national or international collaboration. Given the master’s course’s inter- and multi-disciplinary foundation, the shared framework also facilitates the identification of potential partners in different subject fields.

Different development stages

51The above-mentioned note outlining a common framework for local project partners identified five development stages: (a) program preparation, (b) program support, (c) setting future priorities, (d) looking for the sustainability of the course, and (e) expanding research and teaching capacities.

52Interest in setting up an educational program on CBRN-relevant dual-use technology transfer controls will most likely originate with a small group of advocates, most likely professors or academics, perhaps within a single faculty, possibly as an inter-faculty initiative. The initiative takers will face several questions they must address as a matter of priority in this early stage. Therefore, the first stage of program preparation is articulating the core goals and strategic planning, identifying (learning?) needs, and mobilizing resources. The initiative takers must, therefore, clearly understand initial needs, types of required knowledge and levels of issue awareness, and strategies to engender interest among key decision-making actors and potential target audiences. In constructing their arguments and designing strategies for a successful launch, they also need to consider the circumstances in which their target audiences function. This awareness includes a clear vision of their specific sectorial needs and insights into prevailing levels of awareness about the dual-use potential of their activities.

53Whereas the first stage focuses on the general purpose of the master’s program, program support deals with more detailed planning issues concerning the course set-up that the initiative takers will have to address when facing university decision-makers, government officials (e.g. certifying the program and recognizing degrees), or potential funders. Attracting students will be a primary goal, and having clear and concrete answers available is the bedrock of a promotional campaign targeting the decision-makers mentioned above. The second stage requires balancing ambition and vision with what is feasible from a political, administrative, and resource angle in the present and near future. Furthermore, it involves an idea of how the initiative may evolve over the next few years and a realistic appreciation of risks to the project and ways to avoid, overcome, or mitigate such risks. Questions the initiative takers need to address include clear identification of needs among potential target audiences, including students, government agencies, and relevant economic sectors. They will have to consider whether all the necessary subject competencies are available in their group or whether they will need to approach additional professors. Finally, early funding questions need concrete answers, and if required, they must be able to identify funding sources.

54The third stage, setting future priorities, is also the final preparatory phase, but the course development will likely continue to be refined after its initiation. While the persons involved in setting up a new educational program can reasonably be expected to have a good grasp and overview of the subject matter, they may still benefit from a comprehensive issue-mapping exercise. Those benefits may support arguments to set up the program and provide insights into course planning, work organization, and task distribution. They may also identify linkages to other areas or disciplines supporting multi- and interdisciplinary research and teaching approaches. The initiative takers will also design and begin implementing the educational modules at this stage.

55The next two developmental stages aim to consolidate and sustain the master’s course. The sustainability of the course will depend on several material factors, notably reliable student intake and funding stability. However, making the course viable over a longer period requires investment in immaterial future capacities. It implies investment in reputation among students, peers, and funders. One key aspect to consider in this fourth phase is building and maintaining future capacities. The initiative takers must ensure a sufficient influx of new staff with relevant teaching and research competencies. These can be obtained through external recruitment or the formation of highly qualified graduates at the master’s and PhD levels. Both pathways depend on establishing a highly regarded reputation and course legitimacy. Building networks within their institution and involving experts from other national and international universities and stakeholder communities are essential for these goals. As noted above, having a network available also obviates the need to consolidate all expertise in a single institution. The initiative takers can draw on external competencies for specific tasks.

56The fifth and final stage concerns expanding research and teaching capacities over time. To this end and to ensure continuous development, it is necessary to have a longer-term vision of the educational program and to establish milestones for the teaching and research staff to achieve within well-defined time frames. In addition to specific formal criteria, those milestones should also consider the different preconditions for sustainability. These goals are geared towards forming high-quality graduates and high-level academic and applied research output to support export control policies and their implementation. Their sustained achievement will likely retain the interest and support of decision-makers, funders, and students.

Enabling factors in each development stage

57This networking framework does not represent an obligatory or recommended pathway but instead lays out multiple factors for initiative takers to consider. Therefore, each stage is organized along three sets of factors—needs, knowledge, and visibility—whose consideration and fulfillment may contribute to ensuring and consolidating progress.

-

-

Needs comprise the prior requirements to undertake a particular activity or enable moving to the next stage.

-

Knowledge is critical to establishing the research and educational pillars of the master’s program and the functioning and sustainability of the research base. Knowledge entails:

-

-

awareness about the different issues areas relating to CBRN-relevant dual-use technology transfer controls;

-

the ability to identify future educational and research needs and set future priorities;

-

support for the education and research needs of students; and

-

continuous expansion of academic competencies.

-

-

-

Visibility plays a vital role in the sustainability of the educational and research goals because it enables interactions with key stakeholder communities, including

-

-

outreach to students to encourage them to enroll in the academic program;

-

outreach to decision-makers in faculties, university or research institutions, and government agencies who have a bearing on the authorization, recognition or accreditation of the educational and research program;

-

outreach to industry, professional organizations, and research institutions to broaden the relevancy of the academic and research program (including for promoting a culture of responsibility to prevent proliferation risks, to have them adopt policy recommendations, or for obtaining traineeship positions for students, among other things);

-

building credibility among international organizations, foundations, and other agencies granting funds for research and other relevant projects; and

-

integration and participation in international networks and consortiums.

-

-

-

58The five stages and their respective sets of factors apply to local capacity development and establishing a multi- and interdisciplinary education and research network in a country or region. Each subsequent stage builds on earlier achievements.

A flowchart with options for consideration

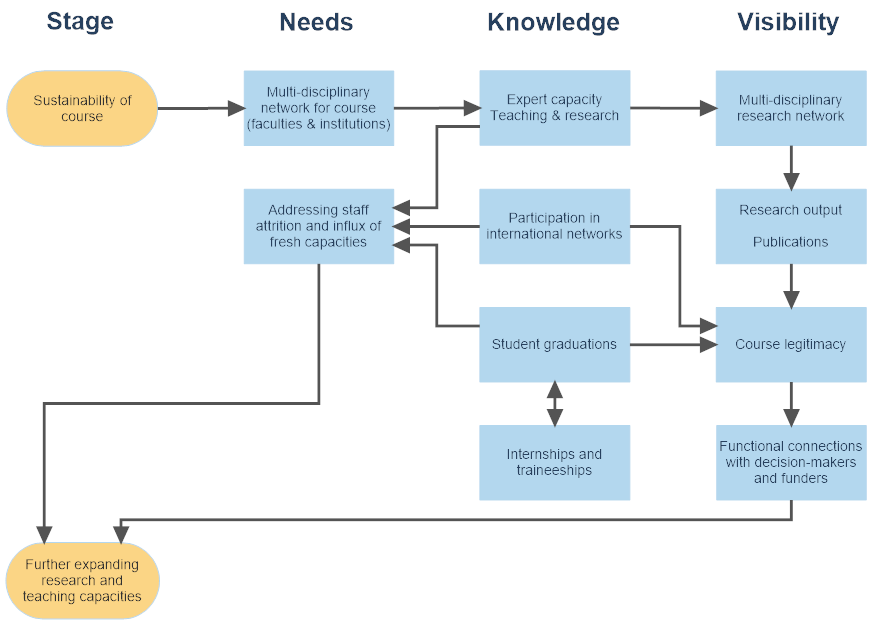

59The five stages and the three sets of factors for each stage make for a complex flowchart that takes up several pages. Figure 2 illustrates Stage 4 focusing on the long-term sustainability of the master’s course. Central elements are knowledge production and organizational resilience, in the function of which, for example, student graduations and personnel attrition are important considerations. Furthermore, the figure illustrates how the outputs of one stage serve as inputs for the subsequent step, facilitating progression toward the fifth and final stage.

Figure EU TI (master) research network: Stage 4 requirements

60The flowchart may serve some secondary functions, too. For instance, when preparing funding proposals, it can aid in identifying concrete project goals, potential risks, and ways to mitigate them. Most importantly, with the flowchart, the project proposers can put forward doable timelines for specific project elements and describe clearly how these will contribute to the ultimate goals. The same applies to project reporting. The flowchart can be a checklist to mark achievements or issues requiring further work.

61When building networks, the potential partners can also use the flowchart to determine the types of capacities they may contribute to the joint endeavor and which ones they may have to develop to become full participants. Institutions with specific capacities useful for more advanced stages may thus be able to assist universities in setting up an export control educational program.

Figure Summary of the processes in the setting up of the master’s course. Legend : purple: setting up the course; yellow: engaging with decision-makers and stakeholder communities; blue: network building

A preliminary assessment of the Targeted Initiatives

62The Targeted Initiatives ended on December 31, 2023, six years after its launch. The present paper was written during the final months of its implementation, making it challenging to fully assess the impact of the education work package. Despite this difficulty, some tangible outcomes can be noted. For instance, in all participating Central Asian and GUAM countries, the respective educational authorities accredited the master’s courses on CBRN-relevant dual-use technology transfers incorporating two or more modules prepared under the Targeted Initiatives. Moreover, students have graduated and found employment in the field of their studies. Perhaps most significantly, teaching activities and program expansions in the partnering academic institutions continued despite the COVID-19 pandemic and, especially in Ukraine, the war.

63In addition to the design of the master’s course, sustainability, local ownership, and network-building were key objectives. Assessing the long-term impact of the Targeted Initiatives is necessarily a future activity. A first detailed evaluation of all work packages within the initiatives, along with recommendations for future projects, should be ready by August 2024. Despite this pending evaluation, the overall impression is positive. Course accreditation and student graduations reduce institutional resistance and motivate the continuation of the activities. Furthermore, the engagement with stakeholder communities and key decision-makers in academia, research institutions, government agencies, and the private sector has created a growing demand for expertise in CBRN-relevant dual-use technology transfer.

64Travel restrictions imposed during and in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as the war in Ukraine, hobbled the in-person dimension of networking. Yet, adopting virtual educational methodologies and online meetings offered unique opportunities to expand engagement with new partners across much larger geographic areas. Online lectures welcomed students from different academic institutions, fostering broader participation and collaboration. Additionally, outreach activities and seminars attracted the interest of high-level decision-makers across multiple universities and research institutions, thereby broadening the understanding of the importance and necessity of the technology transfer educational program.

65The networking efforts continue in 2024. For example, the Caucasus International University in Tbilisi is preparing an edited volume on dual-use technology export controls with financing from the Targeted Initiatives via the STCU. Notably, the authors are local project partners from Central Asia and the GUAM countries. Reflecting on the organization of their educational activities, the local needs, and future plans, two authors from Kazakhstan have summarized their work over the past years as follows:

66“In collaboration with QazTrade and QazIndustry, two quasi-state companies facilitating manufacturing industries and export from Kazakhstan, the project successfully enabled the Eurasian National University (in 2021), Maqsut Narikbayev KAZGUU University (in 2022), Satbayev University (in 2022), Suleyman Demirel University (in 2023), and Kazakh-British Technical University (in 2023) in launching the majors and minors education programmes in Strategic Trade Control.

67The project team members promoted research collaboration with the European Studies Unit at the University of Liege, Belgium and the Center for International Trade Security at the University of Georgia, Athens, USA. [The Central Asian Institute for Development Studies (CAIDS)] also encouraged networking with universities in former Soviet countries,19 such as the Kyrgyz State University in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan, and Kyiv University, Ukraine, with a perspective agenda.

68The long-run sustainability of applied research and education programs is to be attained through (a) increasing advanced knowledge capacity among professors involved in the projects and (b) building multi- and interdisciplinary networks among professors and experts from different faculties in a single university or from different local universities, and, if possible, from universities of other countries participating in the project.

69These national measures reflect Kazakhstan’s commitment to addressing CBRN threats and ensuring the safety and security of its citizens and the broader region. It is important to note that CBRN security is a complex and ongoing challenge that requires continuous monitoring, adaptation, and international cooperation.”20

70The involvement of trade and industry associations, along with the initiation of courses at multiple academic institutions (in this example, in Astana and the Almaty Province), shows the broad recognition of the need for education and engagement in technology transfer controls after sustained investment in outreach. This testimony illustrates the difference between education and training or capacity-building.

Conclusions

71The article underscores the imperative for sustainable efforts in building a culture of responsibility among stakeholders in the target countries, particularly concerning dual-use technology transfers. While many vocational training programs and projects in treaty implementation assistance or norm-strengthening initiatives often falter due to their one-off nature or reliance on external funding, the master’s course, as part of the Targeted Initiatives, sought to buck this trend.

72Central to this ambition is the recognition that mere knowledge transfer will always remain insufficient to shape attitudes. Instead, the master’s course adopted a comprehensive educational approach aimed at enhancing awareness and fostering responsible behavior among audiences. This approach entails not only imparting knowledge but also empowering individuals to identify and assess short-term and longer-term risks and threats, and acquire situational awareness to maintain standards of responsible behavior.

73To fulfill this ambition, the article suggests that institutions in the target countries— universities, research institutes, and other entities dealing with dual-use technology transfers—must become invested in the process. Furthermore, it outlines a three-pronged strategy to advance this goal. First, it emphasizes an educational methodology that places the target audience at the center, ensuring their active engagement in the learning process. Second, it highlights the importance of outreach to key university decision-makers—rectors, faculty deans, and members of educational boards—to persuade them of the need to incorporate education in dual-use technology risk management in the curricula—and to key stakeholders in science, industry, and government agencies. Additionally, the paper underscores the significance of investing in the advanced teaching of professors in the subject matter and assisting in establishing a research base to further academic expertise in the field.

74Furthermore, the article emphasizes the importance of supporting and encouraging local initiatives aimed at building academic and professional networks, both nationally and internationally. These latter aspects not only have significant educational value in their own right but also contribute to fostering local ownership and ensuring sustainability.

75International and national rules on technology transfers appear negative to most key stakeholders. They may constrain research, limit publishing research findings, or impose costs and administrative burdens on industry, trade, and research. Most importantly, they may perceive the constraints as especially burdensome because they do not view themselves as involved in any activity that might contribute to CBRN weapons.

76Education, in contrast, serves as a positive means of engaging relevant scientific, academic, and professional communities. It makes them aware of certain risks related to their work; it encourages them to consider options that reduce or eliminate such risks, to act if they become aware of such risks, and, more generally, it helps them to preserve the legitimacy of their activities.

77Moreover, education offers the advantage of introducing people to risks and threats early in their careers and providing ongoing updates to adapt to evolving settings. Thus, education goes beyond training, the primary objective of which is to augment specific skill sets and expertise to increase task performance. Indeed, education contributes to the establishment and maintenance of a general academic, scientific and professional culture of responsibility that not only affects the daily behavior of individuals, institutions, companies, and government agencies but also creates a shared space for cooperation among all to prevent deliberate or inadvertent technology transfers that could contribute to illicit CBRN weapon acquisition by foreign states or non-state actors.

78In conclusion, the master’s course, along with the broader efforts of the Targeted Initiatives, represents significant steps towards building a culture of responsibility in the realm of dual-use technology transfers. Through sustained educational efforts and collaborative initiatives, stakeholders can work together to address the challenges posed by such transfers and contribute to global security and non-proliferation efforts.

Acknowledgments

This paper reflects the author’s involvement in setting up the master’s program as part of the Targeted Initiatives and the evolution of his thinking. However, the outcomes would not have been possible without the brainstorming sessions, comments, and suggestions of the Targeted Initiative partners over the six-year running period. They include Dr Maria Espona (Argentina), the overall project coordinator, as well as contributions from the work package leaders, Ms Anne Harrington (USA), Dr Richard Guthrie (UK), Dr Kai Ilchmann (Germany), and Prof Dr Quentin Michel (Belgium). The exchanges with academic colleagues in Ukraine and Kazakhstan in setting up the courses were also of great value. Other meaningful experiences and insights came from interacting with interested parties in the Kyrgyz Republic, Tajikistan, Georgia, and Moldova. The same goes for the staff at the ISTC and STCU. I refrain from citing their names or identifying their roles because of the war in Ukraine (and ensure equal recognition of all colleagues).

Notes

1 In the context of the present paper, dual-use technology comprises technologies with “current or potential military and civilian applications”. Molas-Gallart, J., “Dual-use technologies and the transfer mechanisms”, in Technology Transfer, Schroeer and Elena eds., (Ashgate: Aldershot, 2000), p. 5.

2 The reports and comments during formal meetings have over the past years led to diverse education-oriented activities to engage with young students and professionals and stakeholder communities. In the biological field: “UNODA convenes a workshop for young scientists to foster networks on biosecurity in the Global South”, UNODA, August 8, 2019, https://disarmament.unoda.org/update/unoda-convenes-a-workshop-for-young-scientists-to-foster-networks-on-biosecurity-in-the-global-south/; “NTI|bio Bolsters Young Scientists and Promotes Youth Engagement at the 2021 BWC Meeting of Experts”, NTI, September 14, 2021, https://www.nti.org/news/nti-bio-bolsters-young-scientists-and-promotes-youth-engagement-at-the-2021-bwc-meeting-of-experts/; “Youth for Biosecurity, 2022 Cohort”, UNODA, https://disarmament.unoda.org/youth-for-biosecurity-2022-cohort/; “Youth Recommendations for the 9th Review Conference of the Biological Weapons Convention”, YouTube, November 3, 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9DhLVbj8Noc. Because no international organization exists for the Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention, the initiatives are sponsored by state parties, scientific associations, and civil society activities and take place under the auspices of the United Nations.

3 In this context, the term master's course refers to a comprehensive educational program designed to provide in-depth knowledge and skills in a specific field of study, typically at the graduate level. Originally conceived as a standalone master's course comprising 60 credits under the Targeted Initiative, the development process led to adaptations to accommodate various educational contexts.

4 The concept of organizing theme refers to a central theme around which all activities are structured to maintain cohesion among those activities (and participating institutions). This concept is also discussed in: “Report on the Role of Education and Outreach in Preventing the Re-emergence of Chemical Weapons”, ABEO-5/, Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, (12 February 2018), p.6, accessed 16 November 2023. https://www.opcw.org/sites/default/files/documents/2019/03/abeo-5-01_e.pdf

5 “EU P2P Export Control Programme”, Chemical, Biological, Radiological and Nuclear Risk Mitigation, European Union, accessed 16 November 2023, https://export-control.jrc.ec.europa.eu/projects/Dual-use-trade-control.

6 “On other EU activities on Dual-Use Export Controls”, EU P2P Export Control Programme, European Union, accessed 28 April 2024, https://cbrn-risk-mitigation.network.europa.eu/eu-p2p-export-control-programme/dual-use-trade-control_en.

7 Council of the European Union, Strategy Against the Proliferation of Weapons of Mass Destruction, Document 15708/03 (Brussels, 10 December 2003); European Union. (2016). “Shared Vision, Common Action: Strategy for the European Union's Foreign and Security Policy”, European External Action Service, Brussels, June 2016.

8 For further information, see the official website: https://istc.int. The webpage dedicated to the Targeted Initiative is https://www.istc.int/export-control.

9 International Science and Technology Center in Ukraine, accessed October 28, 2023, https://www.stcu.int/. The webpage dedicated to the Targeted Initiative is http://www.stcu.int/tiexpcontrol. (Note: the STCU site is occasionally down because of the war.)

10 “Fact Sheet on DOD Cooperation Threat Reduction (CTR) Program”, US Mission Geneva, April 4, 2022, https://geneva.usmission.gov/2022/04/04/fact-sheet-on-dod-cooperative-threat-reduction-ctr-program-biological-threat-reduction-with-partner-countries/#:~:text=DoD%20CTR%2C%20also%20known%20as,evolve%20into%2015%20sovereign%20states.

11 Details on the four packages envisaged by the Target Initiatives are as follows. WP2 Network of Scientists: this package aimed to raise awareness about CBRN-relevant dual-use technology transfer controls among the scientific and academic communities. It also addressed responsibility and ethics in science and research. WP3 master’s course on export controls: this work package focused on the development of a fully credited university course to educate different stakeholder communities on the risks of dual-use technology transfers and their responsibilities under an export control system.WP4 PhD Grant: the objective of this package was to encourage students to develop a PhD research project in the field of dual-use technology transfer controls and apply for a grant that helped to pay for the time spent as a researcher and research-related costs. The selected students conducted their PhD research at a university with the necessary academic expertise in the EU and, if successful, graduated from that university. WP5 Outreach to Industry: this package aimed to raise awareness among business communities and industry and promoted internal compliance programs. It also developed handbooks and implemented commodity classification courses in collaboration with customs, specialized associations, and non-governmental organizations.

12 D. Rychnovská, “Governing dual-use knowledge: From the politics of responsible science to the ethicalization of security”, Security Dialogue, Vol. 47, No. 4 (August 2016), pp. 310-328. M. Himmel, “Emerging dual-use technologies in the life sciences: Challenges and policy recommendations on export control”, Non-Proliferation and Disarmament Papers, No. 64 (September 2019), p. 15. S. Vinke, I Rais, and P. Millett, “The Dual-Use Education Gap: Awareness and Education of Life Science Researchers on Nonpathogen-Related Dual-Use Research”, Health Security, Vol. 20, No. 1 (February 2022), pp. 35-42.

13 Advisory Board on Education and Outreach, Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (2018). Report on the Role of Education and Outreach in Preventing the Re-emergence of Chemical Weapons. ABEO-5/1 (12 February), accessed November 16, 2023, https://www.opcw.org/sites/default/files/documents/2019/03/abeo-5-01_e.pdf

14 While the initial goal of a 60-credit standalone master's course was not fully realized, the term "full credit" persisted in subsequent writings and presentations. It is worth noting that the term "fully credited university master's course" may better convey the ambition of the program while acknowledging its status may vary depending on the university adopting the course.

15 J. P. Zanders, “Disarmament education: Road-testing a master’s course on CBRN dual-use technology transfer controls”, the Trench Blog (July 21, 2019), https://www.the-trench.org/disarmament-education-road-testing-a-masters-course-on-cbrn-dual-use-technology-transfer-controls. The observations about the internet searches in different locations have led the author to develop a practical guide on structured internet searches, which should become available in the summer of 2024.

16 J. P. Zanders, “Education on CBRN-relevant dual-use technology transfers in Moldova”, The Trench Blog, February 12, 2021, https://www.the- trench.org/education-on-cbrn-relevant-dual-use-technology-transfers-in-moldova.

17 Dr Maria Espona (Argentina) was the appointed overall coordinator of the Targeted Initiative.

18 J. P. Zanders, “Multi-disciplinary research in export controls: Supporting long-term sustainability of the ISTC and STCU Targeted Initiatives”, Note prepared for the ISTC and STCU, and Targeted Initiatives project partners, (2022). (Last revision: 11 May).

19 See International Business and Strategic Trade Control, CAIDS, https://caids.kz/sec/stc.html.

20 K. Moldashev, and G. Makhmejanov, “Regional threats posed by CBRN weapons and their underlying technologies and corresponding measures taken in a regional context”, in J. P. Zanders, and M. Espona, eds., (2024, Forthcoming). Transfer Controls and the Prevention of the Proliferation of CBRN-Relevant Dual-Use Technologies, Tbilisi, Caucasus International University.