- Home

- Volume 1, 2023

- The Extraterritorial Reach of US Export Control Law

View(s): 4080 (11 ULiège)

Download(s): 286 (2 ULiège)

The Extraterritorial Reach of US Export Control Law

The Foreign Direct Product Rules

Attached document(s)

original pdf fileAbstract

In recent years, the United States (US) has dramatically expanded a set of extraterritorial rules, known as the ‘foreign direct product rules’. The rules subject certain items to the jurisdiction of the Export Administration Regulations that are produced outside the US with the use of specific types of US technology, software, or equipment, but contain no US-origin content and are traded between parties outside the US without ever touching US territory. As such extraterritorial rules may breach other States’ sovereign rights, they are only permissible under international law when there is a genuine nexus between the regulating State and the object of regulation. This article argues that, in principle, the foreign direct product rules do not breach international law as US national security concerns, in principle, can justify the rules under the protective principle. The US should, however, better substantiate its decisions to exert its extraterritorial legislative powers to increase acceptance of the rules among affected states.

Table of content

Introduction

1The United States (US) export control law features some special rules with a wide extraterritorial scope subjecting products manufactured outside the US (hereinafter referred to as ‘foreign-made’ or ‘foreign-produced’) to American export control law. One particular set of provisions, called the ‘foreign direct product rules’, subjects certain foreign-made items that are the direct product of controlled US-origin technology or software, or produced in party with equipment that is the direct product of specific types of US-origin technology or software, to the jurisdiction Export Administration Regulations (EAR).1 Consequently, US and non-US citizens or businesses outside the US involved in transactions with these foreign-made items may become subject to US export controls.

2In recent years, the US has significantly extended the reach of the EAR’s foreign direct product rules.2 In 2020 the Bureau of Industry and Security (‘BIS’), the Department of Commerce agency that administers the EAR, amended the foreign direct product rules targeting the Chinese telecommunications company Huawei Technologies Co., Ltd. and hundreds of its subsidiaries worldwide.3 It was the first time the foreign direct product rules targeted a specific business and applied to less-sensitive items.

3Following the further invasion of Ukraine by the Russian Federation (‘Russia’) in February 2022, BIS imposed a series of far-reaching sanctions on Russian4—and Belarusian—5 individuals and entities and further restricted the export to Russia and Belarus. Part of the measures was an extension of the foreign direct product rules, subjecting the shipment to Russia and Belarus from outside the US of a wide range of foreign-made products to US export control law.

4In October 2022, BIS tightened controls over the export to China of advanced chips, computers commodities containing such chips, and chipmaking equipment. The changes that BIS implemented included a further amendment to the foreign direct product rules, expanding its scope to cover foreign-made items “for advanced computing and supercomputer related applications in China.”6 Finally, in February 2023, BIS added Iran to the foreign direct product rules because of its supply of drones to Russia.7

5States can generally enact such laws that apply within their territories as they deem necessary to exercise their sovereign rights. It is now well-accepted that states may also exercise legislative jurisdiction extraterritorially over their nationals, vessels, and aircraft. Further expansion of a state's jurisdiction is more complicated, however. The legislative powers of a State are not without limits since they must be balanced against other states' rights. Extending the scope of national laws beyond national borders may violate the principles of jurisdiction, breaching the sovereignty of other states.

6The foreign direct product rules are a clear example of the extraterritorial exercise of legislative jurisdiction by the US. While the recent amendments to the rules were part of a broader package of changes in US export control law that, as a whole, attracted significant attention, the amended foreign direct product rules did not meet much international criticism. That does not imply that all aspects of the rules are consistent with international law. This paper analyzes to what extent the foreign direct product rules, as part of US extraterritorial export control rules, complies with international law.

7As a backgrounder, the paper starts with a brief overview of export control law before turning to the US rules in this field of law. After a quick exploration of the US export control framework, its extraterritorial provisions are discussed with a particular focus on the foreign direct product rules. Next, the paper turns to international law and analyzes the limits to the jurisdiction of states based on generally accepted principles of jurisdiction. The principles are then applied to the foreign direct product rules. Finally, this paper offers a brief synthesis and conclusion.

Export Control Law

A definition

8As a developing area of law, the parameters of export control law have yet to be fully established. For the purpose of this analysis, I use the following description as a working definition: export control law is a combination of national and international laws and regulations, as well as policy guidelines and international commitments that govern the export, and related activities, of strategic and other items. The inclusion of policy guidelines and international commitments acknowledges the significance of soft law instruments, such as export control regimes (discussed below), in shaping the framework of export control law.

9Export control law governs not only exports but also related activities such as brokering, transit through a country, the export of previously imported items (‘reexport’) and even the transfer within a country to another party. As a result, export control rules can affect not only the exporter of a controlled item but also foreign users, such as the military. For example, armed forces may need to seek permission from the state where equipment was purchased before taking controlled items abroad. For instance, the transfer of Leopard main battle tanks from various states to Ukraine in 2023 required prior authorization from Germany, where the tanks were built.8

10Strategic commodities, software and technology (together referred to as ‘items’)9 include both items specially designed or modified for military use (‘military items’) and items that can be used for civil as well as military purposes (‘dual-use items’). Note that domestic laws and regulations often apply a broader definition. For example, the US Export Control Reform Act of 2018 (‘ECRA’)10 and §772.1 of the EAR include in the definition of dual-use, items that have “…civilian applications and military, terrorism, weapons of mass destruction, or law-enforcement-related applications”. Therefore, the definition of export control law includes the additional phrase ‘and other items’.

International law

11Traditionally, the principal reason for restricting the export of strategic items is a state’s national security. Naturally, a state prefers a possible opponent not to have access to weaponry and military equipment it has designed, developed, or produced. Therefore, the core of export control law is national law. Today, factors other than national security play an increasingly important role, such as preventing the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, promoting international peace and security, contributing to regional stability, and guaranteeing human rights. Various subdisciplines of international law are increasingly concerned with these matters impacting national export control law.

12Traditionally, the laws of war have imposed restrictions or outright prohibitions on the use of certain weapons.11 The field of arms control law has taken a further step, setting limits on the use as well as the research, development, possession, and proliferation of weapons of mass destruction and conventional weapons. Some of the best-known treaties in this area are the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, the Chemical Weapons Convention, the Biological Weapons Convention and the Arms Trade Treaty. Furthermore, human rights law is now a key factor in export control law as states are increasingly considering the human rights situation in the country of destination before approving the export of strategic items.

13States coordinate the implementation and interpretation of the arms control instruments in the so-called multilateral export control regimes. Currently, these are the Wassenaar Arrangement (conventional weapons and dual-use items); the Zangger Committee and the Nuclear Suppliers Group (‘ZA’ and ‘NSG’, nuclear materials and technology), the Australia Group (‘AG’, chemical and biological weapons), and the Missile Technology Control Regime (‘MTCR’ ballistic missiles and unmanned aerial vehicles). These entities lack a formal international legal basis. Therefore, the decisions made by the regimes are in and of themselves not legally binding. Yet, they play a crucial role in export control law as the lists of controlled items they compile find their way into national export control law. As a result, the lists may become legally binding under national law, meaning that the listed items in principle may not be exported without a license or other proper authorization from the relevant state. Also, non-participating states regularly adopt these lists, further reinforcing the authority of the export control regimes.

US Export Control Law

14In the US, export control law comprises “…a complicated, perplexing system of laws and regulations, administered by a host of agencies…”.12 This section of the paper presents a brief overview of the US export control framework to facilitate a better understanding of the US extraterritorial export control rules discussed later on.

15The main legal frameworks for controlling exports of military items and dual-use items are the

16Arms Export Control Act of 1976 (‘AECA’)13 and the Export Control Reform Act of 2018 (‘ECRA’).14 In US legal terms, sensitive military items are defense articles and services under the AECA. This statute is implemented by the International Traffic in Arms Regulations (‘ITAR’),15 which is administered by the Directorate of Defense Trade Controls (‘DDTC’) of the Department of State. All defense articles and services are subject to the jurisdiction of the ITAR and are identified on the US Munitions List (‘USML’), which is part of the regulations.16 The exports and reexports of defense articles and services are subject to licensing requirements, agreements, and exemptions as set out in the ITAR.

17The export, reexport, and in-country transfer of commercial, dual-use items and some military items of lesser sensitivity are subject to the jurisdiction of the EAR. These regulations, which are based on the ECRA and administered by BIS, are much more detailed and complex than the ITAR. They cover almost all items not captured under the ITAR. Furthermore, EAR-controlled items are subject to different licensing requirements and exceptions depending on the reasons for controlling the items,17 the end-use, and the end-user. In general, an export licence or exception is required for items listed on the Commerce Control List (‘CCL’).

The CCL

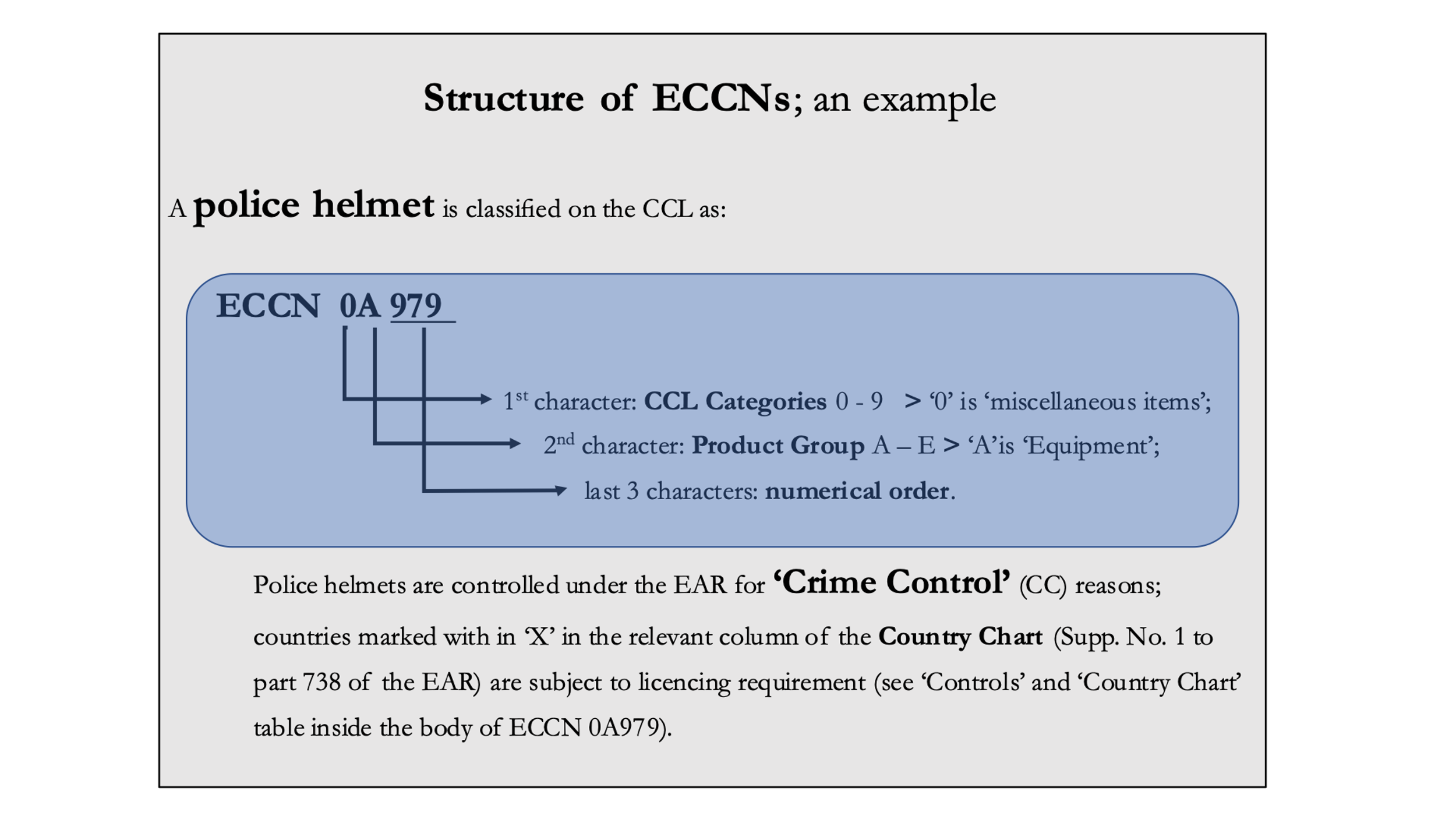

18Items listed on the CCL are classified based on a five-character alphanumeric Export Control Classification Number (‘ECCN’); e.g. 0A979. The first character is a digit in the range 0 through 9 that identifies one of the ten CCL categories in which the ECCN is located. These categories are:

190 – Nuclear Materials, Facilities & Equipment (and miscellaneous items);

201 – Materials, Chemicals, Microorganisms, and Toxins;

212 – Materials Processing;

223 – Electronic Design, Development, and Production;

234 – Computers;

245 – Telecommunications (Part 1) and Information Security (encryption; Part 2);

256 – Sensors and Lasers;

267 – Navigation and Avionics;

278 – Marine;

289 – Aerospace and Propulsion.

29Each category is further divided into five Product Groups as indicated by the second character of the ECCN, which is a letter in the range A through E:

30A – End Items, Equipment, Accessories, Attachments, Parts, Components, and Systems;

31B –Test, Inspection and Production Equipment;

32C – Materials;

33D – Software;

34E – Technology.

35The last three digits are used for the numerical ordering of the item and also indicate the reason for control of the item.

Figure . Breaking down ECCNs; an example.

36Items not listed on the CCL are still subject to the EAR. For ease of reference, these items are classified as EAR99.18 The majority of low-tech consumer products are designated as such and generally do not need a license before exportation.19

37In addition to the list-based controls, there are also end-user controls of unlisted items with the Entity List being a well-known example.20 The list is part of the EAR21— and is, basically, a trade restriction list that identifies persons and entities that pose or may pose a significant risk to US national security or foreign policy interest.22 Inclusion in the list implies that strict licensing requirements limit the export of EAR-controlled items to the listed persons.

Military items subject to the EAR

38Today, the EAR also controls some less significant military items, which were previously subject to the jurisdiction of the ITAR. These items were determined no longer to warrant control under the USML and, consequently, were moved from the USML to the EAR’s CCL as part of the Export Control Reform Initiative.23 In 2013, BIS added a new xY6zz control series for munitions to the CCL (‘600 series’) to each applicable CCL category.24 The series refers to an ECCN that includes the ‘6’ as the third character indicating the entry is a munitions entry formerly subject to the USML.25 The last two characters of the 600 series, the ‘zz’, generally represent the Wassenaar Arrangement Munitions List (‘WAML’) categories for the type of items at issue.

39Shortly after that, BIS created the 9x515 ECCNs for satellites and related systems, such as commercial communications satellites and ground control systems that were previously part of the USML’s satellite section.26 The third character, the ‘5’, is used to distinguish the ECCN from the 600 series and dual-use items not previously on the USML. In 2020, the Department of State concluded that certain firearms, ammunition, and other articles could also be moved to the CCL. Some items were transferred to the existing 600 series of the CCL, while for items that have a civil, recreational, law enforcement, or other non-military use, a new CCL series was created: the 0x5zz series ECCNs. As with 600 series ECCNs, the first character represents the CCL category, the second character represents the Product Group, and the last two represent the WAML category.

Extraterritorial US Export Control Provisions

40US export control laws and regulations apply to items physically present in the US. Furthermore, both the ITAR and the EAR contain several extraterritorial provisions that also subject items outside US borders to its jurisdiction. The US has long taken the position that the reexport of controlled US-origin items remains subject to export control rules.27 However, items manufactured outside the US (‘foreign-produced items’) may also fall under US rules. This type of provisions can be categorized as ‘rule follows the part’ and ‘foreign direct product rules’. The first category covers foreign-produced items that incorporate or integrate a US-origin item. Provisions in this category are present in both the ITAR and the EAR. The provisions of the second category are part of the EAR only and cover foreign-produced items that have been manufactured making use of US technology, software or essential equipment.

Rule follows the part

41Under the ITAR, a controlled part or component that is incorporated in a foreign-produced item continues to be subject to the jurisdiction of the ITAR.28 In other words: integration or incorporation of a defense item in a foreign-produced system or end-item does not change US control over the item. This particular rule is often referred to as the ‘see-through rule’ as “…the ITAR “sees through” the larger system or end-item…”, as it were.29

42The rule is not specified in either the AECA or the ITAR but is a broad interpretation of §120.6 of the ITAR pursuant to which any item described on the USML is a defense article.30 §120.11(c) of the ITAR offers support to the ‘see-through rule’ interpretation.31 This section states that a defense article described on the USML remains controlled following incorporation or integration into any item not described on the USML. This statement of DDTC’s interpretation concerning non-defense articles could, by implication, also be applied to foreign-produced items.32 Moreover, §123.9(e) of the ITAR authorizes reexports or retransfers of US-origin components incorporated into a foreign defense article to certain entities, such as NATO or NATO states, without DDTC’s prior approval, implicating that these US items otherwise would still be subject to the ITAR.

43In the EAR, BIS and its predecessors have taken a completely different approach to shape the ‘rule follows the part’. §734.3(a) of the EAR defines the items that are subject to the regulations, which include, inter alia,

44“(3) Foreign-made commodities that incorporate controlled US-origin commodities, foreign-made commodities that are ‘bundled’ with controlled US-origin software, foreign-made software that is commingled with controlled US-origin software, and foreign-made technology that is commingled with controlled US-origin technology”.33

45These foreign-made items are only subject to the EAR if they contain a certain level (typically 10% to 25% or more; the de minimis level) of commercial or dual-use US-origin components as set out in §734.4.(c) (10% de minimis rule) and §734.4.(c) (25 % de minimis rule) of the EAR.

46Foreign-made items that incorporate more than the de minimis level are treated as US-origin items and are subject to the EAR.34 There is no de minimis level for some foreign-made items if they contain certain high-end US-origin content.35 The latter provision includes, inter alia, specific encryption technology and some of the items formerly on the USML (the 9x515 ECCNs and the 600 series). Under §736.2(2) of the EAR, General Prohibition One, it is not allowed to reexport and export from a country outside the US foreign-made items incorporating more than a de minimis amount of controlled US content without a license or license exception.

Foreign direct product rules

47§734.3(a) of the EAR states that another group of items subject to the EAR is:

48“(4) Certain foreign-made direct products of US-origin technology or software, as described in §736.2(b)(3) of the EAR.”

49This provision refers to the foreign-direct product rules pursuant to which foreign-produced items located outside the US are subject to the EAR when they are a ‘direct product’36 of specified technology or software or “are produced by a plant or major component of a plant that itself is a direct product of specified technology or software” (for easier reference, hereafter the part between quotation marks is summarized as ‘equipment’) (§734.9 of the EAR, introduction).

50In other words, whereas the ‘rule follows the part’ covers foreign-made items that incorporate, bundle, or commingle certain controlled US-origin commodities, software or technology, the foreign direct product rules focus on foreign-made items that have been produced using EAR-controlled, US-origin technology, software or equipment. Under §736.2(3) of the EAR, General Prohibition Three, it is not allowed to export from a country outside the US, reexport, or transfer (in-country) foreign-produced items that are subject to the foreign direct product rules of §734.9 of the EAR without a license or license exception.

51In recent years, BIS has amended the foreign direct product rules several times, reorganizing the rules and adding various sub-rules. Currently, the rules are laid down in §734.9 of the EAR37—and comprises the following specific Foreign Direct Product (‘FDP’) rules:

-

Sub b: National security FDP rule;

-

Sub c: 9x515 FDP rule;

-

Sub d: “600 series” FDP rule;

-

Sub e: Entity List FDP rule;

-

Sub f: Russia/Belarus FDP rule;

-

Sub g: Russia/Belarus-Military End User FDP rule;

-

Sub h: Advanced computing FDP rule;

-

Sub i: Supercomputer FDP rule;

-

Sub j: Iran FDP rule.

52The FDP rules are extraordinarily complex38—and apply when a foreign-produced item meets multiple, often very detailed criteria set out in both the product scope of each rule and the country scope, end-user scope, or destination scope, depending on the character of the specific rule. The product scope of the rules defines when a foreign-produced item meets the criteria laid down in each of the specific FDP rules. Whether the FDP rule applies to the item further depends on the country of destination, the end-user, or the exact destination of the item.

53The national security FDP rule is the original foreign direct product rule, introduced in 1959 and set in its present form in 1996.39 The rule reflects Cold War policy, making foreign-produced items subject to the EAR when the following conditions are met.40 They are the direct product of US technology, software, or equipment that is controlled for national security reasons requiring a written assurance that the ultimate consignee will not reexport the technology to certain countries41—and the resulting non-US made item is also controlled for national security reasons. The country scope of the rule defines for which countries the rule applies by referring to the relevant Country Groups, which are included in the EAR.42 In short, foreign-made dual-use items produced by using sensitive US dual-use technology are controlled as if the items had been produced in the US.43

54Later, particular items that were moved from the USML to the new 9x515 ECCNs (satellites and related systems) and 600 series (munitions) of the CCL were added to the foreign direct product rule. Both the FDP 9x515 rule and the “600 series” FDP rule apply when the foreign-made products are the direct product of US technology, software, or equipment that is specified in certain 9x515 or a “600 series” ECCN and the foreign product is destined for one of the countries mentioned in the relevant Country Groups.

55In 2020, BIS amended the foreign direct product rules by adding the Entity List FDP rule.44 The rule was designed to specifically target the acquisition by China-based telecommunications company Huawei Technologies Co., Ltd. and a number of its non-US affiliates (collectively referred to as ‘Huawei’)45 of certain semiconductors. Huawei was, however, not mentioned in the FDP rule itself. Instead, the new rule created a footnote (‘footnote 1’) to the Entity List that was added to Huawei. As a result, certain foreign-made items that were a direct product of specific EAR-controlled US technologies, software, or equipment and were produced or developed by an entity with a footnote 1 designation on the Entity List (so Huawei and its listed affiliates) or products of Huawei software or technology, became subject to the EAR.46

56BIS further tightened restrictions on Huawei in August 2020 by adding another 38 Huawei affiliates to the Entity List and amending the Entity List FDP rule.47 The amended rule no longer required foreign-produced items to be produced or developed by Huawei or to be the products of Huawei software or technology. Instead, a license requirement was imposed on foreign-made items when there is knowledge the item will be incorporated into, or will used in the production or development of parts or equipment made for Huawei, or when Huawei is a party to such transactions (e.g., as a purchaser or an end-user). In other words: the rule applies regardless of the role Huawei plays in the export-related transaction. According to BIS, the rule can even control foreign-produced commercial-of-the-shelf and other basic EAR99 items.48

57In 2022, BIS amended the EAR, complementing the numerous sanctions imposed by the US, the EU, and like-minded states on Russia and Belarus because of the further invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.49 Part of the EAR amendment was the creation of two new FDP rules as part of the Russia Sanctions rule of March 2012.50 A week later, BIS published the Belarus Sanctions rule51—subjecting Belarus to the same licensing requirements that were imposed on Russia the week before. Inter alia, BIS added Belarus to the two new FDP rules and renamed both rules in the Russia/Belarus FDP rule and the Russia/Belarus Military End User FDP rule. In February 2023, BIS further amended the Russia/Belarus FDP rule following Iran’s supply of drones to Russia.52

58The product scope of the former rule subjects foreign-produced items to the EAR when they are the direct product of US technology, software, or equipment that is specified on the CCL and the foreign product is a specific subset of EAR99 item53—or is specified in any ECCN on the CCL. Furthermore, the destination scope requires knowledge that the foreign-produced item is destined for Russia or Belarus. This is the first time a foreign direct product rule is applied to entire countries.

59The Russia/Belarus Military End User FDP rule applies to military end users in Russia and Belarus and elsewhere who are identified with a (new) Footnote 3 designation in the Entity List.54 The rule applies to all foreign-produced items that are direct products of US technology, software, or equipment specified in certain categories of the CCL.55 Also, the end-user scope of the rule requires the involvement in a transaction of the designated Russian and Belarusian military end-users, e.g., as a purchaser or an end-user.

60In October 2022, BIS introduced new amendments to the EAR designed to limit the production and development by China of items such as advanced node semiconductors, semiconductor production equipment, advanced computing items and supercomputers.56 As part of this broader approach, BIS expanded the Entity List FDP rule and introduced two new foreign direct product rules: the advanced computing FDP rule and the supercomputer FDP rule. Through this set of rules, the US seeks to limit China’s access to advanced items necessary for the further development of Artificial Intelligence (‘AI’).57

61BIS added a new Footnote 4 to the Entity List and designated the first 28 Chinese entities under this footnote. Under the expanded Entity List FDP rule, foreign-made items that are the direct product of EAR-controlled semiconductor, computer, or telecommunications technology, software, or equipment are subject to the EAR if one of the following two conditions of the end-user scope of the rule is met. There must be either knowledge that the foreign items will be incorporated into or be used in the production or development of any part or equipment produced, purchased, or ordered by a footnote 4 entity on the Entity List or knowledge that a footnote 4 entity is a party to any transaction involving the foreign-produced item, e.g., as a purchaser or end-user.

62The product scope of the new advanced computing FDP rule subjects foreign-produced items that are the direct product of specific EAR-controlled semiconductor, computer, telecommunications, or encryption technology, software, or equipment to the EAR. Also, the foreign items must either be specified in one of the new ECCNs for advanced computing integrated circuits (and related equipment, software and technology) or be an integrated circuit, computer, electronic assembly, or component specified elsewhere on the CCL and meets specific performance parameters. The rule applies when there is either knowledge that the item is destined for China or will be incorporated into any part, computer or equipment on the CCL that is destined for China, or technology developed by an entity headquartered in China for the production of a mask or an integrated circuit wafer or die.

63The product scope of the other new rule, the supercomputer FDP rule, subjects foreign-produced items that are the direct product of specific EAR-controlled semiconductor, computer, telecommunications, or encryption technology, software, or equipment to the EAR. The country and end-use scope of the rule require that the foreign item is used in the design, development, production, operation, installation, maintenance, repair, overhaul, or refurbishing of, a supercomputer located in or destined for China or is incorporated into, or used in the development or production, of any part or equipment that will be used in a supercomputer located in or destined for China.

64In February 2023, BIS introduced the Iran FDP rule to address the use of Iranian drones by Russia in the war against Ukraine.58 The rule is modelled after the Russia/Belarus FDP rule but with a special focus on Iran’s drones activities. Under the rule, a foreign-produced item is subject to the EAR when it is the direct product of US-origin technology, software, or

65equipment specified in certain categories of the CCL and the foreign item is a specific subset of EAR99 items59—or is specified in certain categories of the CCL. Also, there must be knowledge that the foreign-produced item is destined to Iran or will be incorporated into or used in the production or development of any part, component, or equipment, identified in supplement no. 7 to part 746 of the EAR or is specified in certain categories of the CCL that is located in or destined to Iran.

Jurisdiction of the state

66The previous section outlined a, perhaps, unique set of extraterritorial provisions. In particular, the foreign direct product rules have an astonishing extraterritorial reach subjecting foreign-made items to US law based on the thinnest nexus with the US imaginable. The foreign-produced items contain no tangible controlled US parts and are manufactured outside the US. The mere use of specific US technology, software, or equipment in the manufacturing process serves as the link that subjects the foreign-produced item to US law.

67In today’s increasingly interconnected world, it may be necessary for states to extend their legislative powers beyond national borders in order to regulate persons and activities. However, such extraterritorial rules when pertaining to export controls, may limit the trade opportunities of other states, potentially causing international tension and burdening persons and businesses abroad. Therefore, the extraterritorial exercise of legislative jurisdiction is limited by law, in particular, the principles of jurisdiction.

Principles of jurisdiction60

68Jurisdiction is fundamental to the functioning of international law as it is an essential characteristic of a sovereign state. It pertains to its capacity under international law to make laws, subject individuals and property to legal processes based on these laws and compel compliance with the rules when necessary.61 These three powers are known as the state’s legislative, enforcement, and adjudicative jurisdiction.62 In this paper, the focus is on legislative jurisdiction (also known as ‘prescriptive jurisdiction’), which refers to “… the authority of a state to make law applicable to persons, property, or conduct”, whether by legislation, by an executive act, or by determination of a court.63

69The exercise of legislative jurisdiction is limited by “the sovereign territorial rights of other states”64 as jurisdiction and the exercise thereof are typically considered to be territorial in nature.65 However, states may extend the scope of their laws beyond national borders based on a permissive rule of international law. Such a rule is part of customary international law,66 which allows a state to exercise legislative jurisdiction extraterritorially based on a genuine connection between the state seeking to regulate and the persons, property, or conduct being regulated.67 That connection is reflected in a set of principles: the territoriality principle, the nationality principle, the protective principle, and the universality principle. Therefore, the exercise of national legislative jurisdiction has to rest on one or a combination of the principles.

70The principle of territoriality is the central element in the jurisdictional framework68—and ‘…is the oldest, most common, and least controversial…’ jurisdiction principle.69 It reflects the right of a state to enact laws applicable within its territory, but this principle is also relevant to events that partially occur outside the legislating state’s border. The generally accepted principle of objective territoriality allows the state to assert its legislative jurisdiction over an event if an essential element of an action that commenced abroad was completed within the state’s territory.70 The concept of objective territoriality serves as the basis for the ‘effects doctrine’, which was developed in the US.71 This doctrine permits the exercise of legislative jurisdiction over acts performed abroad by foreign persons or companies that have a “direct, substantial and reasonably foreseeable…”72 economic effect on the regulating state. Despite ongoing controversy, the ‘effects doctrine’ is garnering increased acceptance, particularly in the field of antitrust law.73

71Another principle that plays a crucial role in the jurisdictional framework is the nationality principle. Generally, a distinction is made between the nationality principle, also known as the active personality principle and the passive personality principle. The former pertains to the nationality of the person who engages in an act abroad that has no direct connection to the territory of the legislating state. Under this principle, a state has the authority to assert legislative jurisdiction over its nationals, even when they are outside of the state’s territory.74 An example is §744.6(b)(5) of the EAR,75 which prohibits US persons, wherever located, from supporting a ‘military-intelligence end use’ or a ‘military-intelligence end user’ in certain states.

72The nationality principle also applies to the international activities of corporations that are incorporated or constituted under the law of the legislating state.76 US regulations, regularly extend US jurisdiction also over foreign-incorporated companies that are ‘owned or controlled’ by US persons.77 This so-called control theory, that is based on the nationality principle is, however, not generally accepted under international law.78

73The application of the active personality principle is well-accepted as opposed to the application of the passive nationality principle, which focuses on the nationality of the victim of an act performed abroad. Under this principle, a state can apply its legislative jurisdiction to certain acts performed outside its territory harming its nationals. Although the passive personality principle is still controversial, its use has become more accepted with respect to certain crimes, especially terrorist-related crimes.79

74The protective principle (or: ‘security principle’),80 constitutes a well-accepted legal basis for legislation with extraterritorial scope.81 It is based on the conduct of an individual that poses a threat to the sovereignty, integrity, or security of the legislating state, rather that his or her status. As such, a state can only assert legislative jurisdiction under this principle when its vital interests, such as its internal or external security or financial and monetary stability, are at risk. Typical examples of actions that justify extraterritorial legislation under this principle are espionage, counterfeiting of the state’s currency and an extraterritorial conspiracy to evade the state’s immigration laws.82 Since such acts do not necessarily harm the interests of the state where the action was initiated and may, therefore, not be subject to the laws of that state, extraterritorial application of the legislative state’s laws is justified.83

75Universal jurisdiction pertains to legislation suppressing certain recognized crimes under international law, such as piracy, slavery, war crimes, genocide, and certain acts of terrorism. Unlike the principles discussed above that require a direct or an indirect link between an act and the state asserting jurisdiction, the principle of universality does not necessitate such a link. The principle builds on the idea that the nature of the crimes, or of the circumstances under which they are committed, are deemed to be a universal concern. Therefore, any state may take legislative action. Today, a number of international agreements oblige states parties to exert their legislative jurisdiction over the most serious international crimes.84

US extraterritorial export control law and the principles of jurisdiction

76In principle, US statutory law, as enacted by Congress, applies only within the territory of the US. However, if Congress clearly demonstrates an intent to extend the legislative reach beyond US borders, US laws and regulations can have an extraterritorial effect.85 This legal construction called the ‘presumption against extraterritoriality’,86 limits the exercise of legislative jurisdiction.87 The AECA and the ECA, both enacted by US Congress, are exceptions to this rule as they are clearly intended to apply extraterritorially, focusing on the control of the export of US-origin items, which explicitly includes the regulation of reexports.88 Consequently, specific extraterritorial legislation such as the ITAR’s ‘see-through’ rule and the EAR’s foreign direct product rules are permissible under US law.

77The US has to exert its extraterritorial prescriptive powers per the principles recognized under customary international law as described above.89 However, the broad scope of US export control law raises concerns about its consistency with these principles. This issue previously came to the forefront over 40 years ago when a number of states and the predecessor to the EU, the European Community, successfully challenged an amendment to the EAR, which introduced extraterritorial controls to the existing oil and gas controls targeting the Soviet Union90—sometimes referred to as the ‘Siberian pipeline case’.91

78This amendment was unprecedented in its extraterritorial scope restricting US-owned or controlled companies outside the US from exporting certain foreign-origin oil and gas equipment and technology (‘technical data’) to the Soviet Union.92 Additionally, the amendment revised the (predecessor to the) national security FDP rule93—that at the time restricted the export of foreign-produced items that were manufactured using “…US technical data if the export of the data was subject to the receipt of a written assurance from the foreign importer against the transfer of the data or its products to proscribed destinations.”94 The Department of Commerce deemed the amendment essential for advancing the foreign policy objectives of the US.

79The European Community was quick to condemn the extraterritorial export restrictions95—concluding that the measures were a violation of their sovereignty and illegitimate, breaching international law “… since they cannot be validly based on any of the generally accepted bases of jurisdiction in international law.”96 Intensive diplomatic consultations followed, leading to an agreement between the US and its allies on Western trade issues with the Soviet Union.97 As a result, President Reagan lifted the pipeline controls, among other measures, on 13 November 1982.98

The protective principle

80The absence of critical voices does not impact the question of the compatibility between the extraterritorial rules and the principles of jurisdiction. To answer this question, it is necessary to determine if there is, based on the principles, a genuine nexus between the US as regulating state and the persons, property, or conduct being regulated.99 This section will focus on the foreign direct product rules only.100

81US export control law emphasizes the US-origin of the controlled items. This focus may suggest that US nationality is attached to such items, thereby justifying the active personality principle as the legal basis for the extraterritorial rules. However, this notion is inconsistent with international law, as an object cannot have a personality.101 Therefore, the nationality principle cannot justify the extraterritorial scope of the foreign direct product rules.102 Since the primary reason for restricting the export of strategic items is to ensure national security, as stated above, the protective principle may be a more appropriate basis for justifying the extraterritorial export control provisions.

82Given the considerable variation in the scope provisions of the FDP rules, it is necessary to evaluate each rule separately or in combination to determine the relationship between the rules and national security concerns. That relationship is abundantly clear in the national security FDP rule, which explicitly subjects foreign-made items to the EAR when US technology, software, or equipment is used that is controlled for national security reasons. The 9x515 FDP rule and the “600 series” FDP rule both deal with technology, software, or equipment previously listed on the USML, as discussed above. Even though the control of the items under the ITAR was no longer warranted, strict controls remained necessary under the EAR because of the sensitive nature of the controlled items. As a result, with very few exceptions,103 the US technology, software, or equipment to which both the 9x515 FDP rule and the “600 series” FDP rule refer to manufacture the foreign-made items, are controlled for national security reasons. The use of sensitive US technology, software, or equipment to produce a foreign-made item an adversary of the US could use against the country, would jeopardize US security. Therefore, the FDP rules can be justified under the protective principle.

83The perceived risk of Huawei’s involvement in activities contrary to the foreign policy interest of the US as well as its threat to US security, led to the introduction of the Entity List FDP rule in 2020.104 Specifically, the US was concerned that because of Huawei’s ties with the Chinese government and military,105 the Chinese government might gain access to confidential information in US telecommunications systems through secret ‘backdoors’ in systems supplied by Huawei.106 Such unauthorized access to US telecommunications systems can be qualified as a contemporary form of espionage, which warrants extraterritorial regulation based on the protective principle.

84National security concerns were also part of the decision to introduce the Russia/Belarus FDP rule and the Russia/Belarus-Military End User FDP rule. BIS stated that the measure taken against Russia were necessary to protect US national security and foreign policy interests as they would restrict “…Russia’s access to items that it needs to project power and fulfil its strategic ambition….”.107 The subsequent measures imposed on Belarus followed a similar approach stating that the measures were required to limit “…Belarus’ access to items that it needs to support its military capabilities and preventing such items from being diverted through Belarus to Russia”.108

85The FDP rules targeting China were designed to restrict the development and production in China of advanced node semiconductors, semiconductor manufacturing equipment, advanced computing items and supercomputers. According to the US, China uses these items and systems to become the world leader in AI by 20230, which enables the country to develop and produce advanced military systems, including weapons of mass destruction, and improve its military decision-making, planning, logistics, and autonomous military systems.109 Losing leadership in computer-related technologies and AI to China would, therefore, impact US national security.110

86Finally, the delivery of Iranian drones to Russia led to the introduction of the Iran FDP rule and the amendment of the Russia FDP rule. As the use of the drones would enhance Russia’s defense industrial base and its military efforts against Ukraine, the US argued it would be contrary to its security and foreign policy interests.111

87This evaluation shows that the US has consistently based the amendments of the foreign direct product rules at least partly on national security concerns. It may well be that the explicit reference to national security is a lesson learned from the 1982 Siberian pipeline case. At that time, the US stated that the amendment to the EAR, including the foreign direct product rules, was driven by foreign policy concerns. As these concerns cannot justify the extraterritorial exercise of its legislative jurisdiction under the protective principle or any other jurisdiction principle, it provided the European Community with a solid argument to challenge the amendments.112

88Although the protective principle is a well-established principle of jurisdiction that can justify extraterritorial legislation under international law, it should be emphasized that the principle is not well-defined as the categories of possible vital interests of a state, such as its national security or financial and monetary stability, are not closed.113 As the principle also pertains to the legislating state’s own interests, it could be prone to abuse if that state defines its security interests too broadly. Therefore, the legislating state should clarify why the extraterritorial exercise of its legislative powers is necessary to protect its national security interests, in particular when activities do not always align well with the actions typically seen as constituting a national security threat or foreign-produced items made from minimally controlled technology (such as EAR99 items).

89A case in point is the Chinese development of emerging technologies, such as AI, using advanced AI chips, design software and computers, which is a far cry from traditional activities targeted by extraterritorial legislation based on the protective principle, such as espionage and counterfeiting. As a result, it is a big step to justify legislation aimed at regulating such activity using this protective principle. However, given the potential challenges that AI poses, we must recognize that we are entering uncharted waters. It is, therefore, conceivable that the US feels compelled to restrict the use of its technology, software and equipment to produce items, which could serve China’s technological advancement, posing a threat to US security.

90Moreover, the US position cannot be separated from China’s ‘Military-Civil Fusion’ initiative, whereby technological developments in the civilian sector should, among other things, serve the development of the military sector by breaking down the barriers between China's civilian research and commercial sectors and its military and defense industrial sectors.114 This initiative would allow emerging technologies, such as AI, to be further developed for military use, potentially giving China military dominance. Whether other countries actually support the US position remains to be seen, although the current lack of critical voices can easily be mistaken for acquiescence. This is not without challenges because it cannot be ruled out that the US will further expand the foreign direct product rules to restrict other technologies .115

91While the US, in general, has made it clear that national security is a principal reason for amending the foreign direct product rules, the arguments it has put forward are somewhat general and do not always clearly demonstrate how a particular amendment contributes to the protection of US national security, justifying a possible breach of the sovereign rights of other states. This is particularly true for the Russia/Belarus and the Iran FDP rules. It appears the US partly acknowledged this challenge and created a carve-out for allied and partner States listed on the ‘Russia Exclusion List’.116 Listed states have committed to implementing export controls on Russia and Belarus that are substantially similar to those imposed by the US and are, therefore, exempted from both FDP rules.117 This move was likely a preemptive measure to avoid any criticism from its allies similar to what was expressed in the 1982 Siberian pipeline case. There is no such carve-out for the Iran FDP rule, likely because US trade restrictions are still more strict than the measures other states have imposed on Iran.

Synthesis and Conclusion

92Export control law is an emerging legal discipline that covers the complex framework of laws and non-legal commitments pertaining to the export of strategic and other commodities, technology, and software. Traditionally, export control law is domestic in nature as national security was the prime concern for controlling these items. Today, US export control law is the dominant national export control framework because of the magnitude of US military and dual-use exports as well as its broad extraterritorial scope.

93Extraterritorial export control provisions in US laws and regulations can be found in the ITAR, which regulates the export of defense and articles and services, and the EAR, which covers commercial, dual-use and less sensitive military items. As the U.S-origin of the items is the starting point for regulation under both the ITAR and the EAR, the export of a US-origin item from a state outside the US to another state (reexport) remains, in principle, subject to US export control rules. Also, items manufactured outside the US (‘foreign-produced items’) can be subject to both regulations. Under the ‘rule follows the part’, foreign-made items can be subject to either the ITAR or the EAR when certain controlled US-origin commodities, software, or technology are incorporated, bundled, or commingled. Under the EAR’s foreign direct product rules, foreign-made items that have been produced using certain EAR-controlled, US-origin technology, software, or equipment may also be subject to US law.

94Such an exercise of legislative jurisdiction is limited by the sovereign territorial rights of other states. As a result, extraterritorial legislation is only allowed under a permissive rule of international law that establishes a genuine connection between the state seeking to regulate and the persons, property, or conduct being regulated.118 That connection is reflected in four principles of jurisdiction: the territoriality principle, the nationality principle, the protective principle, and the universality principle.

95A considerable part of the US-origin items covered by the extraterritorial provisions is controlled due to national security concerns. Therefore, the protective principle can provide the legal basis for most of the extraterritorial provisions in the ITAR and EAR. However, the scope of some of the FDP rules is quite broad, making it challenging to reconcile them with the protective principle, even though all recent amendments to the FDP rules consistently emphasize the need to address US national security concerns. This difficulty is particularly true for the 2022 China FDP rules, the Russia/Belarus FDP rule, the Russia/Belarus Military End User FDP rule and the Iran FDP rule. It appears the US seeks to preempt potential legal challenges to the former two rules by exempting its allies on the Russia Exclusion List from their applicability.

96It can be concluded that, in general, the extraterritorial foreign direct product rules are consistent with international law as the rules can be justified under the protective principle. Although the scope of some of the FDP rules is broad and, in some situations, they cover minimally controlled items, it is essential for the US to clearly outline the arguments underlying its decisions to exert its legislative powers extraterritorially. Providing a well-supported and robust justification for any further amendment to the extraterritorial rules will increase their acceptance by states affected by the rules. Such justification will be more persuasive than exempting a selected group of states from the rules’ application.

Notes

2 E.g. “The history and limits of America’s favourite new economic weapon”, The Economist, February 8, 2023, https://www.economist.com/united-states/2023/02/08/the-history-and-limits-of-americas-favourite-new-economic-weapon.

3 85 Federal Register (‘Fed. Reg.) 51596 (October 20, 2020).

4 87 Fed. Reg. 12226 (March 3, 2022).

5 Belarus was target of the sanctions because of its substantial enabling the Russian invasion. See 87 Fed. Reg. 13048 (March 8, 2022).

6 “BIS Imposes New Controls to Limit the Development and Production of Advanced Computing and Semiconductor Capabilities in China”, International trade alert, Akin Gump, October 27, 2022, p. 12, https://www.akingump.com/a/web/dPkFKYAkdYwpiDGPT5RzQz/4v9EH8/international-trade-alert.pdf

7 88 Fed. Reg. 12150 (February 27, 2023). Drones are also known as ‘Unmanned Aerial Vehicles’ or ‘Unmanned Aircraft Systems’.

8 Under German law export licences for military equipement, such as the Leopard tank, include strict reexport requirements, one of which is prior German approval of the reexport; News and Alerts, “Germany’s Leopard headed for Ukraine”, WorldECR (Issue 116), February 2023, p 3.

9 Cf. the definition of ‘item’ under the Export Control Reform Act (‘ECRA’) 2018 and §772.1 of the EAR.

10 50 United States Code (‘U.S.C.’) 4801 et seq.

11 See, for example, the 1899 Declarations concerning Asphyxiating Gases (IV, 2) and concerning Expanding Bullets (IV, 3); both The Hague, 29 July 1899.

12 Eric L. Hirschhorn, Brian J. Egan, and Edward J. Krauland, U.S. Export Controls & Economic Sanctions, 4th edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2022, p. xxiii.

13 Arms Export Control Act of 1976, (22 U.S.C. 2751 et seq.).

14 50 U.S.C 4811 et seq.

15 22 C.F.R Section 120–130.

16 §121.1 of the International Traffic in Arms Regulations (‘ITAR’).

17 The four broad categories of reasons for controlling the items are: national security, foreign policy, non-proliferation of weapons of mass destruction and short supply; Hirschhorn, Egan, and Krauland, U.S. Export Controls, p. 5.

18 §734.3(c) of the EAR.

19 A license may be required when an EAR99 item is to be exported to an embargoed country, to a party of concern, or in support of a restricted end-use.

20 Kevin J. Wolf, “Congress gives BIS new authorities to control US-person activities”, WorldECR (Issue 116), February 2023, pp. 26-29.

21 Supplement no. 4 to part 744 of the EAR.

22 §744.16 of the EAR.

23 Ian F. Fergusson and Paul K. Kerr, “The U.S. Export Control System and the Export Control Reform Initiative,” Congressional Research Service, January 28, 2020.

24 Revisions to the Export Administration Regulations: Initial Implementation of Export Control Reform, 78 Fed. Reg. 22660, at 22661 (April 16, 2013).

25 The 600 series also cover thirteen Wassenaar Arrangement Munitions List (WAML) entries that were already on the CCL under xY018 (78 Fed. Reg. 22660, at 22661 (April 16, 2013).

26 Revisions to the Export Administration Regulations: Control of Spacecraft Systems and Related Items the President Determines No Longer Warrant Control Under the United States Munitions List (USML), 79 Fed. Reg. 27418 (May 13, 2013).

27 Restatement of the law fourth, § 402, para 9.

28 From 2013 on, some parts, including items like fasteners (e.g., screws, bolts, nuts) washers, spacers, etc. are excluded from the rule when they are not ‘specially designed’; cf. Fergusson and Kerr, “The U.S. Export Control System”, p. 16.

29 ITAR/USML Updated Frequently Asked Questions, accessed March 8, 2023, https://www.pmddtc.state.gov/ddtc_public%3Fid=ddtc_public_portal_faq_detail&sys_id=8a8b2d9cdb3d5b4044f9ff621f961993?id=ddtc_search&q=See-through#:~:text=Answer:%20The%20phrase%20“%20see-through%20rule”%20is%20a,described%20on%20the%20USML%20is%20a%20defense%20article.

30 ITAR/USML Updated Frequently Asked Questions.

31 87 Fed. Reg. 16396, at 16397 (March 23, 2022).

32 87 Fed. Reg. 16396, at 16397.

33 This subsection is subject to the de minimis level of U.S. content as set out in §734.4. of the EAR.

34 §734.4. of the EAR.

35 §734.4.(c) of the EAR.

36 The EAR defines ‘direct product’ as “The immediate product (including processes and services) produced directly by the use of technology or software”; see the definitions in Part 772 of the EAR.

37 See: BIS Final Rule, Foreign-Direct Product Rules: Organization, Clarification, and Correction; 87 Fed. Reg. 6022 (February 3, 2022).

38 “BIS Imposes New Controls”, Akin Gump, p. 12.

39 Kevin J. Wolf et al.,“US Government Clarifies, Reorganizes and Renames Descriptions of How Foreign-Produced Items Outside the United States Are Subject to US Export Controls as the US Contemplates New Restrictions on Russia” Akin Gump, February 9, 2022, p. 2, https://www.akingump.com/en/insights/alerts/us-government-clarifies-reorganizes-and-renames-descriptions-of-how-foreign-produced-items-outside-the-united-states-are-subject-to-us-export-controls-as-the-us-contemplates-new-restrictions-on-russia

40 61 Fed. Reg. 12719 (March 25, 1996).

41 See: Paragraph (o)(3)(i) of supplement no. 2 to part 748 of the EAR.

42 Supplement no.1 to part 740 of the EAR.

43 “BIS Imposes New Controls”, Akin Gump, p. 11.

44 85 Fed. Reg. 51596 (Oct. 20, 2020).

45 Earlier, BIS had added Huawei Technologies Co., Ltd. and 68 of its non-U.S. affiliates to the Entity List; 84 Fed. Reg. 22961 (May 21, 2019).

46 In particular semiconductor-related items (Cat. 3 ECCL), computers (Cat. 4 ECCL), and telecommunication items (Cat. 5).

47 85 Fed. Reg. 51596 (October 20, 2020).

48 "Foreign-Produced Direct Product (FDP) Rule as it Relates to the Entity List § 736.2(b)(3)(vi) and footnote 1 to Supplement No. 4 to part 744”, Frequently Asked Questions, BIS, updated 28 October 2021, https://www.bis.doc.gov/index.php/documents/about-bis/2681-2020-fpdp2-faq-120820-ea/file

49 See: “U.S. Government Imposes Expansive, Novel and Plurilateral Export Controls Against Russia and Belarus”, International trade alert, Akin Gump, March 8, 2022, https://www.akingump.com/a/web/ayCoxfB41bXG1H8Y4jUWup/3FFMet/us-government-imposes-expansive-novel-and-plurilateral-export.pdf.

50 Effective 24 February 2022; 87 Fed. Reg. 12226 (March 3, 2022).

51 Effective 2 March 2022; 87 Fed. Reg. 13048 (March 8, 2022).

52 88 Fed. Reg. 12150 (February 27, 2023); the amendment ensures that certain EAR99 items controlled under the new Iran FDP rule will be similarly controlled to Russia and Belarus.

53 As identified in Supplement no. 6 or 7 to Part 746 of the EAR; the latter supplement was introduced in 2023 with the Iran FDP rule (see below).

54 For example, on January 31, 2023, BIS added seven Iranian entities involved in the manufacture of drones to the Entity List as Russian ‘Military End Users’; 88 Fed. Reg. 6621 (February 1, 2023).

55 So, including EAR99 items.

56 87 Fed. Reg. 62186 (October 12, 2022); §734.9 on the FDP rules is effective October 21, 2022.

57 E.g. Gregory C. Allen, “Choking of China’s Access to the Future of AI. New U.S. export controls on AI and semiconductors mark a transformation of U.S. technology competition with China”, Center for Strategic & International Studies, October 2022; “America’s commercial sanctions on China could get much worse. And China could retaliate much worse”, The Economist, March 30, 2023, p. 3.

58 88 Fed. Reg. 12150 (February 27, 2023).

59 As identified in the new Supplement no. 7 to Part 746 of the EAR.

60 This section is based on Joop Voetelink, “Limits on the Extraterritoriality of United States Export Control and Sanctions Legislation”, in NL-ARMS: Netherlands Annual Review of Military Studies 2021, Compliance and Integrity in International Military Trade, ed. By Robert Beeres, et al. (The Hague: T.M.C. Asser Press, 2022) pp. 192-195.

61 J.E.D. Voetelink, Status of forces: criminal jurisdiction over military personnel abroad (Berlin/Heidelberg: Asser Press/Springer, 2015), p. 116.

62 It must be noted, however, that outside the United States adjudicative jurisdiction is not always recognized as a separate category of jurisdiction; Restatement of the law fourth, § 401, Reporters’ Notes.

63 Restatement of the law fourth, The foreign relations law of the United States. Selected topics in treaties, jurisdiction, and sovereign immunity (St. Paul: American Law Institute Publishers, 2018), § 401(a) and Introductory Note and § 407. Enforcement allows a State “to exercise its power to compel compliance with the law.” (Ibid. § 401(c). Adjudicative jurisdiction expresses the authority to: “… apply law to persons or things, in particular through the processes of its courts or administrative tribunal” (Ibid. § 401(b).).

64 Banković and others v. Belgium and 16 others, App no 52207/99, § 59, the European Court of Human Rights, December 12, 2001.

65 The case of the S.S. Lotus, Series A. No. 10, the Permanent Court of International Justice, September 7, 1927, pp. 18-19.

66 Jurisdiction under international law is primarily regulated by customary international law; Restatement of the law fourth, § 401, Comment.

67 Restatement of the law fourth, § 407, Comment.

68 C. Ryngaert, Jurisdiction in international law 2nd ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), p. 36.

69 Restatement of the law fourth, § 408, Reporters’ Notes, para 1.

70 E.g. J. Crawford J., Brownlie’s principles of public international law, 9th ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019), p. 442.

71 U.S. courts developed the doctrine in antitrust cases. The Alcoa-case was the first case in which a U.S. court accepted the doctrine: United States v. Aluminium Corp. of America, 148 F.2d 416 (2d Cir. 1945).

72 Restatement of the law fourth, § 408, Reporters’ Notes, para 6.

73 Restatement of the law fourth, § 409, Reporters’ Notes, para 2; Laurent Cohen-Tanugi, “The extraterritorial application of American law: myths and realities,” February 2015, p. 11. See, for instance the Gencor-case in which the Court of First Instance of the EU hold that application of a particular EU Regulation “…is justified under public international law when it is foreseeable that a proposed concentration will have an immediate and substantial effect in the Community”. ECJ 25 May 1999, Gencor Ltd v Commission of the European Communities, Judgment of the Court of First Instance (Fifth Chamber, extended composition); European Court Reports 1999 II-00753, Case T-102/96, ECLI:EU:T:1999:65, at paragraphs 89–92).

74 Ryngaert, Jurisdiction in international law, p. 104.

75 This section implements section 4812(a)(2)(F) of the ECA; Wolf, “Congress gives BIS new authorities”, p. 27.

76 Cf. Barcelona Traction case in which the International Court of Justice found that under international law the nationality of a corporation is determined by its place of incorporation; ICJ 5 February 1970, Case Concerning Barcelona Traction, Light, and Power Co., Ltd (Belgium v. Spain), Second Phase, I.C.J. Reports 1970, p. 3, paragraph 70.

77 E.g. secondary sanctions; see: Voetelink, “Limits on the Extraterritoriality”, pp. 211-212.

78 Restatement of the law fourth, § 410, Reporters’ Notes, para 2.

79 E.g., Crawford J., Brownlie’s principles of public international law, p. 445. And example is Article 6(2)(a) of the Terrorist Bombings Convention, which instructs State Parties to establish jurisdiction over acts set forth in the Convention when “the offence is committed against a national of the State; International Convention for the Suppression of Terrorist Bombing, New York, December 15, 1997 (Vol. 2149 UNTS 2003, No. 37517), entered into force May 23, 2001.

80 Crawford J., Brownlie’s principles of public international law, p. 446.

81 Ryngaert, Jurisdiction in international law, p. 114.

82 Christopher Staker, “Jurisdiction”, in International Law, ed. Malcolm D Evans (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014) p. 321.

83 Ryngaert, Jurisdiction in international law, p. 114.

84 E.g., Articles 49 and 50 of the Convention (I) for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armed Forces in the Field; Geneva, 12 August 1949 (Vol. 970 UNTS 1950, No. 970). And Article V of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide; 9 December 1948 (Vol. 78 UNTS 1951, No. 1021).

85 E.g. Note Michigan Law Review, “Extraterritorial application of the Export Administration Act of 1979 under international and American law”, Michigan Law Review, Vol. 81, Issue 5 (1983), p. 1313.

86 Restatement of the law fourth, § 404.

87 As was confirmed in the Aramco-case; U.S. Supreme Court 16 January 1991, EEOC v. Arabian American Oil Co., 499 U. S. 244 (1991).

88 Voetelink, “Limits on the Extraterritoriality”, p. 205.

89 Restatement of the law fourth, § 401, Comment.

90 E.g. H.E. Moyer and L.A Mabry, “Export controls as instruments of foreign policy: the history, legal issues, and policy lessons of three recent cases”, Law and Policy in International Business, Vol. 15, no. 1, (1983), pp. 60 ff. These measures were implemented in regulations issued pursuant to the Export Administration Act of 1978 (47 Fed. Reg. 141, at 144 (January 5, 1982)).

91 J. Ashley Roach, “Extraterritorial Application of U.S. Export Controls. The Siberian Pipeline,” Proceedings of the Annual Meeting (American Society of International Law), Vol. 77 (April 1983), pp. 252 and 264.

92 Roach, “Extraterritorial Application of U.S. Export Controls,” p. 251.

93 §379.8 of the EAR.

94 47 Fed. Reg. 27250 (June 24,1982).

95 Moyer and Mabry, “Export controls as instruments of foreign policy”, pp. 81-82.

96 On August 12, 1982 the EC presented a Note to the U.S. Dept. of States together with the legal “European Communities: Comments on the U.S. Regulations concerning trade with the U.S.S.R.”; European Communities: Comments (1982), para. 30.

97 Moyer and Mabry, “Export controls as instruments of foreign policy”, pp. 83-84.

98 47 Fed. Reg. 51858 (November 18, 1982).

99 Restatement of the law fourth 2018, § 407, comment.

100 The author has previously analyzed the legality of the reexport provisions and ‘rule follow the part’ provisions in Voetelink, “Limits on the Extraterritoriality”, p. 206.

101 European Communities: Comments, para. 8. The comments added that “…there are no known rules under international law for using goods or technology situated abroad as a basis of establishing jurisdiction over the persons controlling them.” Also, see Note Michigan Law Review, “Extraterritorial application of the Export Administration Act of 1979 under international and American law”, Michigan Law Review, Vol. 81, Issue 5 (1983), p. 1313.

102 Voetelink, “Limits on the Extraterritoriality”, p. 206.

103 Some items are controlled for reasons such as ‘Anti-Terrorism’ and ‘Regional Stability’.

104 85 Fed. Reg. 29849, at 29850-1 (May 19, 2020).

105 Jill C. Gallagher, “U.S. Restrictions on Huawei Technologies: National Security, Foreign Policy, and Economic Interests”, Congressional Research Service, January 5, 2022, p. 6.

106 Stephen P. Mulligan and Chris D. Linebaugh, “Huawei and U.S. Law”, Congressional Research Service, February 23, 2021.

107 87 Fed. Reg. 12226 (March 3, 2022).

108 87 Fed. Reg. 13048 (March 8, 2022).

109 87 Fed. Reg. 62186 at: 62186-7 (October 12, 2022).

110 Cf. “Remarks by National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan at the Special Competitive Studies Project Global Emerging Technologies Summit”, Briefing Room, the White House, September 16, 2022.

111 88 Fed. Reg. 12150 (February 27, 2023).

112 European Communities: Comments, para. 13.

113 Christopher Staker, “Jurisdiction”, in International Law, ed. Malcolm D Evans (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014) p. 321.

114 “The Chinese Communist Party’s Military-Civil Fusion Policy”, U.S. Department of State, accessed March 8, 2023, https://2017-2021.state.gov/military-civil-fusion/index.html

115 “America’s commercial sanctions", The Economist, pp. 4-5, https://www.economist.com/briefing/2023/03/30/americas-commercial-sanctions-on-china-could-get-much-worse

116 Supplement No. 3 to Part 746 of the EAR.

117 As of February 24, 2023; the list includes the EU member States, Australia, Canada, Iceland, Liechtenstein, Japan, New Zealand, Norway, South Korea, Taiwan, Switzerland, and the UK.

118 Restatement of the law fourth, § 407, Comment.

To cite this article

About: Joop Voetelink

Dr. Joop Voetelink is Associate Professor of Law at the Faculty of Military Sciences of the Netherlands Defence Academy. He is involved in the Master’s Programme ‘Compliance and Integrity in International Trade’, where he specializes in export control law. Dr. Voetelink research interests lie in export control law in general and in the area of extraterritorial legislation, developments in sanction law, and the regulation of emerging technologies in particular. This article is part of dr. Voetelink’s research under the auspices of the Amsterdam Center for International Law at Amsterdam University and the Research Center Military Management Studies at the NLDA. The author is grateful to the participants in the online workshop ‘The Arms Trade and the Law, 2022-2023’ for their valuable comments on an earlier draft of this article. However, any errors are the author’s responsibility.