- Portada

- Volume 12 : 2012

- Varia

- The Effectiveness of Intergovernmental Lobbying Mechanisms in the American Federal System

Vista(s): 10820 (41 ULiège)

Descargar(s): 0 (0 ULiège)

The Effectiveness of Intergovernmental Lobbying Mechanisms in the American Federal System

Abstract

The national and state governments share power in the American federal system. However, to the chagrin of states, the federal government often has the upper hand in intergovernmental relations. This article explores how state legislators perceive the health of federalism in the United States and examines the tools that they use to influence policy enactment and implementation in Washington, DC. It concludes that states are less than sanguine about federal-state relations and that they use a wide array of tools to take their message to the federal government even though they question their effectiveness.

Tabla de contenidos

1. Introduction1

1At the core of American federalism is the idea that power and responsibility should be shared by the federal and state governments. As with any relationship, the health of federalism is dependent on the ability of these governments to communicate, especially when dealing with policy issues that cross jurisdictional lines. Previous research has focused on providing deep descriptions of different mechanisms of communication, however little is known about how state legislators perceive these mechanisms. This article examines five tools for transference of state policy preferences to the federal government from the perspective of state legislatures: procedural safeguards, peak intergovernmental lobbying organizations, individual state offices in Washington, DC, coalition lobbying, and memorials to Congress. Our research shows that state legislators are largely dissatisfied with the health of American federalism and believe that few tools exist to improve it. These findings suggest that if the health of federalism is to improve, more effective mechanisms of communication must emerge.

2. The Allocation of Decision-making in American Federalism

2American constitutional design is predicated on the preservation of personal rights through an elaborate set of power-sharing mechanisms. Separation of powers, checks and balances, representative democracy, the extended republic and federalism were incorporated to prevent any one faction or individual from accumulating too much power within government2. The American system of government divides power between equally sovereign states and a national government. According to James Madison in Federalist Paper # 51:

“the power surrendered by the people, is first divided between two distinct governments, and then the portion allotted to each, subdivided among distinct and separate departments. Hence a double security arises to the rights of the people. The different governments will control each other; at the same time that each will be controlled by itself”3

3This system of non-centralized government allows citizens to appeal to multiple levels of governments to preserve their rights and to express their policy preferences.

4Unlike many other federal countries, the United States does not have an explicit list of jurisdictional boundaries over specific policy issues4. Elazar argues that the “federalism of the Constitution was crystal clear, just as the division and sharing of powers was left ambiguous”5. Article I, Section 8 of the U.S. Constitution describes the powers enumerated to Congress and the Tenth Amendment states that the “powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people”. This allocation of the powers between the federal and state governments has never been neatly operationalized. In fact, the Supreme Court has interpreted other sections of the Constitution to allow for federal action that crosses the jurisdictional boundaries of the enumerated powers. The Founders included the “elastic clause” of the Constitution which grants Congress the authority to “make all Laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into Execution the foregoing Powers, and all other Powers vested by this Constitution in the Government of the United States, or in any Department or Officer thereof (Article I, Section 8).” Beginning with McCulloch v. Maryland (1819), the Supreme Court has interpreted the implied powers doctrine liberally. The Supreme Court also supported increased federal activities during the 20th Century under the auspices of their ability to regulate interstate commerce6. The effect has been to greatly increase Washington’s scope of policy activity and to muddle the boundaries of the division of powers in the American federal system7.

5Many policy issues in the United States are administered by all levels of government, either cooperatively or because the Constitution grants each government concurrent powers. In most cases collaborative exercises in public policy have emerged from areas that were traditionally state and local responsibilities. While few areas of policy are wholly constructed and administered by any one level of government, Table 1 exhibits a “sorting out” of functions among the different levels of government.

Table 1. Taxonomy of Selected Policy Responsibilities within the American Federal System

6However, the taxing and spending power of the federal government allows it to intrude heavily into areas that are typically state and local responsibilities. The federal government may not ultimately control these areas of policy, but it provides numerous grants to state and local governments that influence the construction and implementation of programs. For example, federal interference in K-12 education particularly through the No Child Left Behind Act has rankled the feathers of state’s rights advocates and illustrates the federal governments intrusion into policy areas traditionally left to the states.

7The muddling of boundaries between federal and state authority has evolved through various phases throughout American history. The fluid boundaries of policy authority have allowed for different models of power sharing to emerge depending on the political environment. The evolution of American federalism has resulted in a system of governance with fluid boundaries of authority for policy. Intergovernmental relations had always shown traces of cooperation8. However, cooperative federalism reached its climax in the mid-twentieth century following the New Deal9. By the 1970s Washington’s collaboration with the states entered into a coercive period as the federal government increasingly imposed policy prescriptions on the states without their consent. Using policy tools such as preemption, unfunded mandates, matching requirements and cross-cutting sanctions, the federal government was able to expand their influence and become the dominant partner in the American political system10. By the turn of the twenty-first century the old forms of politics based on “boundaries of institutional responsibility” were replaced by an opportunistic federalism where actors “pursue their immediate interests with little regard for the institutional or collective consequences”11. Thus policy preferences and political considerations supercede the mechanics of intergovernmental relations. State and local governments are but one of many competing interests seeking to affect federal policy in this new political arrangement. Consequently they are forced to focus on gaining the most advantageous form of intergovernmental collaboration as opposed to seeking to keep Washington, DC from encroaching on their policy autonomy12.

3. Tools for Transference of State Policy Preferences

8Morton Grodzins, in his classic work on American federalism entitled The American System, argues that most policy activities in the United States are shared between governments. However, in many cases there is one level of government that is “preponderant”. The federal government can usually assert itself through offering grants to state governments to achieve its objectives. States, on the other hand, have to assert themselves either politically or through professional associations13. Most of the research in intergovernmental influence since The American System has sought to fill in the specifics of Grodzin’s assertions. The resulting options for policy transference to preserve the interests of states are what William K. Hall has called the extra-governmental institutions of federalism14. This concept of public sector politics encompasses “people in their public capacities trying to influence government action”15. The literature highlights five primary tools that states use in attempt to get their voices heard in Washington, DC and to protect their interests: the procedural safeguards option, intergovernmental lobbying groups, individual state offices in Washington, DC, collaborative mobilization with interest groups, and memorials to Congress.

3.1 The Procedural Safeguards Option

9Arguing for a majority of the Supreme Court in Garcia v. San Antonio Metropolitan Transit Authority (1985), Justice Blackmun argued that “[s]tate sovereign interests…are more properly protected by procedural safeguards inherent in the structure of the federal government than by judicially created limitations on federal power”16. The theory posits that Congress has the authority to make policy in any area regardless of the traditional lines of authority that have been established between states and the national government. States, without specific constitutional protections protecting their authority, are forced into the hyper-pluralistic fray of interest group politics. Unlike other advocacy groups state officials have an advantage because they are publicly elected officials who represent some of the same constituents as their fellow members of Congress. The electoral congruence makes members of Congress more likely to heed the requests of state officials because they want to maximize their reelection potential. Consequently the procedural safeguards option theory claims that the intergovernmental objectives of state officials will be reflected in the activities of their state’s delegation in Washington, DC. The success or failure of this method of preference transference relies on the ability of state officials to activate a web of interpersonal contacts based on geographical proximity and partisan identification that allows federal officials to recognize the needs and priorities of their state17.

3.2 Intergovernmental Lobbying Through Collective Organizations

10The second tool for preserving the interests of states is through organizing professional associations of state government officials. Termed intergovernmental lobbying groups (IGR), organizations such as the National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL) and the National Governors Association (NGA) reach consensus positions on issues of importance to state governments. These organizations represent the broad policy needs of elected state officials. Scholars in this field have focused on the agendas of peak IGR groups18. Much like peak business associations, these IGR groups can be effective voices for state government when they are internally unified and when they coalesce with other state and local groups to present a united front to Congress19. However, unity is difficult. The organizations were formed to represent the interests of state governments as institutions within the American federal system. Status as governors or state legislators does not ensure that consensus will emerge within the peak associations. Regionalism, ideology, party, population and personality characteristics are internal dynamics that make consensus difficult20. The groups will not take stances on issues where there are divisions within their membership. Consequently, the generalist associations remain silent on some issues that affect federalism, leaving individual states to lobby on their own.

3.3 Individual State Offices in Washington, DC

11States do not rely solely on the NGA or NCSL to speak on their behalf. Many states have their own Washington, DC offices in order to advocate their discrete interests to the federal government. The peak IGRs lack the time or resources to become involved in the particularistic details of every state government’s need before the federal government.

12States appear most likely to use their Washington, DC offices to advocate for their particularistic needs while leaving theoretical questions of federalism to the peak IGR organizations. The Washington, DC offices allow states to remain abreast of federal developments that will affect their constituency and to rapidly respond by providing the legislative or executive branch with information as to how policies will affect their state21. Washington, DC offices are overwhelmingly operated at the behest of a state’s governor, who has the authority to open or close an office. Benefits accrued from the Washington, DC Office invariably benefit both the state and the political fortunes of the governor. Jensen argues that there are three main benefits: 1) they procure federal funding through line item grants or by achieving favorable funding formulas in large federal programs; 2) they help achieve policy goals, often by procuring a waiver allowing an individual state to administer a federal program or regulation with flexibility; and 3) they help accrue political benefits such as visibility and prestige for individual governors22. The addition of these political considerations on behalf of individual politicians means that these offices often advocate for more than just the federalism interests of a state. However, they still represent a tool of state policy transference worthy of study.

3.4 Interaction with Non-IGR Interest Groups

13State officials have special access in Washington, DC because federal officials respect the fact that they are accountable to the public and because they have experience implementing federal programs23. This is a form of privileged position because federal officials are interested in hearing the experiences of the intergovernmental lobby. However, access does not automatically translate into policy success because federal officials are more concerned about policy outcomes than federalism. Nugent argues that “[i]t is admittedly difficult to cleanly separate a state government’s interests from the interests of certain constituencies within a state such as businesses, industries, or other groups”24. Consequently state governments also build coalitions that will lobby on behalf of specific policies having material effect on discrete members of their constituency. The use of this tool employs meetings with interest groups where strategies can be hashed out to mobilize the resources of non-governmental groups to push for Congressional action25. Coalition politics are necessary for state officials because they represent broad spatial (or geographic) interests as opposed to policy interests represented by traditional pressure groups. Other groups or organizations may focus on the geographical venue where decisions are made26. However, these groups focus on spatial issues as a means to defeat their policy opponents by limiting or expanding the scope of conflict. This is unlike the intergovernmental lobby, which is concerned with the place of the state and local governments in the federal system. The differences in interests make it advantageous for state actors to coalesce with outside groups to achieve their policy preferences.

3.5 Memorials to Congress

14The final method for states to voice their policy preferences to Washington, DC is through the use of memorials to Congress. These are resolutions that have passed one or both houses of a state legislature. They are fundamentally designed to voice explicit preferences supporting or opposing federal action across a wide range of policy issues27. These memorials have been an understudied method of preference transference and are, therefore, a fundamental part of this study. Memorials to Congress from subnational governments equate to private Petitions. While the right to petition is integral to the concept of free speech, memorials were rooted in concepts of representation and federalism. Memorials in the United States predated the founding of the Republic28. They continued to be used in the new Constitutional system although their meaning was the subject of great debate. The primary issue was whether memorials were “instructions” from the state legislatures that must be adhered to strictly by members of Congress. The U.S. House and Senate rejected this concept when they voted down a proposal to include “the right to instruct” in the First Amendment29. Direct election of House members meant that state legislatures had little recourse to punish non-compliers. Consequently, memorials to the House merely “requested” votes in line with state wishes30.

15State legislatures had a different view of the autonomy of the Senate since they chose its membership. Most of the conflict between state legislatures and their Senators over the binding effect of instructions occurred prior to the Civil War31. However, states continued attempts at instruction into the early twentieth century32. The lack of a recall mechanism to replace non-responsive Senators prohibited any meaningful punitive action on behalf of state legislatures33. The passage of the 17th Amendment resulted in memorials becoming mere “requests” for the Senate as well as the House. Despite these changes, states actively memorialize Congress on a broad array of issues. Consequently, these memorials represent another tool for states to register their policy preferences with the federal government34.

4. Methodology

16This study examines these five tools of preference transference in an attempt to understand which are the preferred methods for state legislators and which they think are most effective. In 2009 we designed and distributed a mail survey to state legislators in five states. The purpose of the survey was two-fold. The first objective was to measure state legislator’s perceptions of the health of contemporary state-federal relationships. The second objective was to analyze how state legislators attempt to relate their policy preferences to the federal government and the perceived effectiveness of those mechanisms.

17The five state legislatures surveyed for this article were Alaska, Massachusetts, South Dakota, Virginia and Washington. These states were selected to maximize variability on a number of measures: Elazar’s political culture classification35, geographic region, political ideology, partisanship, and legislative professionalism (please see Appendix A for a breakdown of each state’s characteristics). Two variables of particular importance in state selection are party competition and legislative professionalism. Party competition is an important variable in analyzing intergovernmental relations because of its potential impact on legislators’ opinion of federalism. Legislative chambers that are controlled by a single party are likely to be less approving of the state of federalism if their rival party is the dominant party in Washington DC. Likewise, legislative chambers are likely to be more approving of the state of federalism if their party is the dominant party in Washington DC. The states range from one-party Republican (Alaska and South Dakota) to one-party Democrat (Massachusetts) and include two-party competitive states (Virginia and Washington).

18Another important variable is a state legislature’s institutional capacity to carry out their legislative functions. States with more capacity and resources will be able to concern themselves with issues that fall outside of their basic functions. This means that states with more capacity may be more active and inventive in communicating their policy preferences to Washington DC. State legislatures’ institutional capacity to handle this increased workload was measured through their legislative professionalization ranking36. Legislative professionalization measures how closely state legislatures resemble the United States Congress in staffing levels, days in session and legislator compensation37. In general, those legislatures with a higher score have more institutional capacity than those states with lower professionalization scores. The five states selected for inclusion into this study range from a highly professionalized legislature (Massachusetts), to moderately professionalized legislatures (Alaska and Washington), and citizen legislatures (South Dakota and Virginia).

19Following Dillman’s Tailored Design Method38, multiple mailings were sent to every member in the upper and lower chambers of our selected state legislatures. Copies of the survey were sent to legislators’ capitol offices except in South Dakota. Considering South Dakota legislators are in session for a short period of time, surveys were sent to their district offices instead of their capitol offices. In Massachusetts, a low initial response rate to the capitol mailing prompted an additional mailing to the legislators’ district offices. A total of 105 surveys were completed and returned (for a more detailed description of response rates see Appendix B).

5. A Strained Partnership: Why States Need to Use Intergovernmental Tools

20Before we evaluate what tools states use to voice their opinions to the federal government it is important to understand why they need to use these mechanisms. If the federal government automatically took state interests into account when making policy there would be no need for states to express their preferences. However, if the states dislike federal activities and their role within the federal system, then they are more likely to employ ways to voice their dissatisfaction. We address this relationship by employed two questions in our survey that assess how state legislators view the “health of American Federalism.”

21First, legislators were asked to rate the relationship between the federal government and their state government on a scale of 1 (poor) to 5 (excellent). The responses indicate that state legislators view the health of federalism as being relatively poor. Approximately 80 percent say the relationship is between 1 (poor) and 3 (satisfactory) with a 2.64 average. As illustrated in Table 2, this level of dissatisfaction with state-federal relations is consistent across all five states in the study.

Table 2. Health of Federalism (Average)

22Our second assessment of the health of federalism asked the legislators to indicate how much power each level of government possesses (where 1= too little and 5= too much). The responses showed that state legislators viewed the federal government as the most powerful level of government in the United States. Unfortunately they were dissatisfied with this since almost 41 percent of the respondents believe that the federal government has “too much” power.

23State legislators are unhappy with the existing relationship between states and the federal government and they think Washington, DC has too much power. If they were pleased with the behavior of the federal government there would be less incentive to actively use the mechanisms of intergovernmental influence examined below. However, their dissatisfaction shows that state legislators need to use these tools in an attempt to preserve their place in the federal system.

6. Mechanisms of Intergovernmental Influence

24One of the most important questions for scholars of intergovernmental relations is how states voice their opinions about policy to the federal government. Our survey measures both the frequency of use, and the perceived effectiveness of, the five aforementioned mechanisms of preference transference available to the state. The results show that while state legislators have a number of mechanisms available to them, not every mechanism is equal. Our data shows that, sensibly, those mechanisms that receive the greatest usage are also the ones that are thought to be most effective.

6.1. Intergovernmental Mechanism Usage

25At a base level we desire to know which intergovernmental lobbying tools are used by state legislators. Consequently we measured the frequency by which state legislatures use popular tools of intergovernmental lobbying. These tools include: working with intergovernmental lobbying groups, sending a state memorial to Congress, meeting with members of the state’s congressional delegation, working with state legislative/governors office representatives in Washington DC, and working with interest groups.

26Respondents were asked to rate on a scale of 1 (not at all) to 5 (very frequently) how frequently they use five different tools to communicate their policy preferences to Washington DC. As illustrated in Table 2, the results show that as a group, state legislators demonstrate the greatest likelihood of working with their congressional delegation when faced with a federal-state policy issues. Specifically, the responses show that meeting with their congressional delegation is the most frequently used tool (3.5 average response) followed by working with an intergovernmental lobbying groups (3.2) and the state legislative/governor’s office representative in Washington DC (3.2). Meeting with an interest group (2.9) and using memorials to Congress (2.6) were the least popular tool as reported by state legislators.

Table 3. Intergovernmental Mechanism Usage

27Sorting the data by state, party, and satisfaction level of federal/state relationships, some additional findings emerge. First, some states are more likely to use these mechanisms than other states. Alaska is the most active state, we hypothesize, because of the vast geographic distance between Juneau and Washington DC.

28Second, Republicans are slightly more active in using these mechanisms than are Democrats. Both parties, however, are most likely to consult with their congressional delegation and least likely to send a memorial to Congress when faced with a federal/state policy issue. Finally, those legislators who are dissatisfied with the federal/state relationship are slightly more likely to use these mechanisms.

6.2. Intergovernmental Mechanism Effectiveness

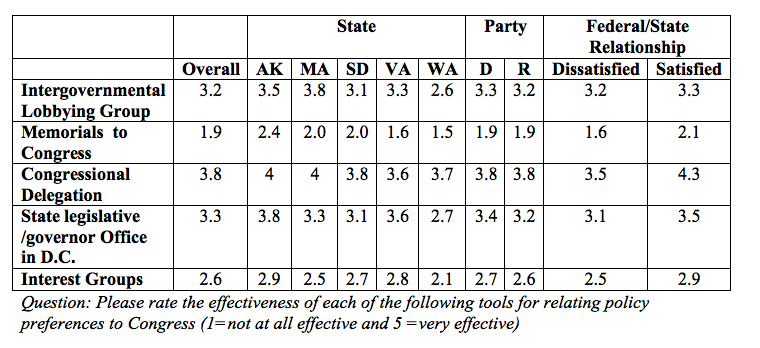

29State legislators were also asked to rate how effectively each of the mechanisms transmit their state’s policy positions to Washington, DC. Examining the results in Table 3, it is clear that some mechanisms are perceived as being more effective than others.

Table 4. Intergovernmental Mechanism Effectiveness

When asked to rate the effectiveness of the mechanisms on a scale of 1 (not effective) to 5 (very effective) state legislators’ believe that meeting with their congressional delegation is the most effective mechanism (average 3.8). This explains why it is also the most frequently used mechanism, as described above. This was followed by meeting with state legislative/governor’s office representatives in Washington DC (3.3), working with intergovernmental lobbying groups (3.2), meeting with interest groups (2.6), and sending memorials to Congress (1.9).

When asked to rate the effectiveness of the mechanisms on a scale of 1 (not effective) to 5 (very effective) state legislators’ believe that meeting with their congressional delegation is the most effective mechanism (average 3.8). This explains why it is also the most frequently used mechanism, as described above. This was followed by meeting with state legislative/governor’s office representatives in Washington DC (3.3), working with intergovernmental lobbying groups (3.2), meeting with interest groups (2.6), and sending memorials to Congress (1.9).

30Parsing the data, Alaska state legislators were the most optimistic about the effectiveness of these tools while Virginia and Washington were the most skeptical. Again, the perceived effectiveness of the mechanisms lines up nicely with the usage of those mechanisms. Democrats were slightly more likely to perceive these mechanisms as being effective than Republicans, and those who are satisfied with the current state of federalism are much more likely to perceive them as being effective than are legislators who are dissatisfied with the state of federalism. This last point illustrates that the health of American democracy could improve if the effectiveness of these mechanisms also improve.

7. Memorials to Congress

31Memorials have received little attention in the literature so we will explore their use and effectiveness in more detail than the other mechanisms of intergovernmental influence. Memorials to Congress are used frequently by state legislatures, with 4119 submitted from 1987-200639. Our survey shows that 51% of the respondents introduced at least one memorial during a two year legislative session with an average of more than three memorials over the same period. However, from the data discussed above, we can see that memorials are viewed as being largely ineffective. The survey showed that state legislators believe they have little effect because politicians and bureaucrats in Washington DC pay little attention to them.

32If memorials are ineffective, why are they so numerous? Our data suggests two reasons. First, memorials are important in that they give state legislators a vehicle to transmit their preferences to Congress. The text of the memorials is then entered into the daily Congressional Record, which serves as the official record of the proceedings of the United States Congress. As one state legislator noted, memorials are “the only tool we have to get the federal government’s attention.” Another legislator said that memorials provide Congress with “insight into what the impact will be on a state level.”

33Second, memorials contribute to the larger scope of agenda setting and deliberation occurring in Washington, DC. One state legislator claimed that memorials might influence the agenda if “a critical mass of states express the same policy goal”.40 Another respondent stated that memorials have a greater impact as part of a larger “grass roots” effort that combines the legislature’s position on an issue with lobbying by organizations from their state. At a minimum, memorials appear to help reinforce arguments already being made by a state’s advocates. Consequently memorials are a useful tool in understanding what states want from the federal government.

8. Conclusion

34The American federal system is based on power sharing between the national and state governments. The processes of intergovernmental relations develop over time with Washington, DC having the upper hand in the federal partnership because of its ability to fund programs, enact mandates and preempt state laws. Our data has shown that state legislators believe that relations between the states and the federal government are mediocre. They also feel that Washington, DC has the most power within the intergovernmental system, coming at the expense of state and local governments.

35However, this article shows that state legislators are not passive actors when it comes to federal-state relationships. Few state legislators sit idle when Washington DC considers policies that impact their state. Rather they use a combination of tools in an attempt to take their message to the federal government. Our data show that not all mechanisms are thought to be equally effective. State legislators viewed direct communications with their state delegation and working with intergovernmental lobbying groups as the most effective means of stating their case to the federal government. Coalescing with interest groups and sending memorials to Congress were viewed as being less effective means of stating a state’s case to the federal government. More broadly, the data show that states desire to have their voice heard in Washington DC, but have few effective mechanisms available to them to help them achieve it. In all, the data point to the difficulty of communication between state legislatures and the federal government.

Appendix

Appendix A: Characteristics of Survey’s State Legislatures

Appendix B: Mail Survey Returns

References

36Agranoff (R.), ‘Managing within the Matrix: Do Collaborative Intergovernmental Relations Exist?’, Publius: The Journal of Federalism, vol. 31, 2001, p. 31-56.

37Allen (D. G.), ‘The Zuckerman Thesis and the Process of Legal Rationalization in Provincial Massachusetts’, William and Mary Quarterly, vol. 29, 1972, p. 443-460.

38Arnold (D. S.) and Plant (J. F.), Public official associations and state and local government: A bridge across one hundred years, Fairfax, George Mason University Press, 1994.

39Beer (S.), ‘Federalism, Nationalism, and Democracy in America’, American Political Science Review, vol. 72, 1978, p. 9-21.

40Beyle (T.) and Muchmore (L.), ‘Governors and Intergovernmental Relations: Middlemen in the Federal System’, in Beyle (T.) and Muchmore (L.), Being governor: The view from the office, Durham, Duke Press Policy Studies, 1983, p. 192-205.

41Brooks (G. E.), When governors convene: The governors’ conference and national politics, Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1961.

42Cammissa (A. M.), Governments as interest groups: Intergovernmental lobbying and the federal system, Westport, Praeger, 1995.

43Cigler (B.), ‘Not just another special interest: Intergovernmental representation’, in Cigler (A. J.) and Loomis (B.), Interest group politics, Washington, DC, CQ Press, 1995, 4e edition, p. 131-153.

44Conlan (T.), ‘From Cooperative to Opportunistic Federalism: Reflections on the Half-Century Anniversary of the Commission on Intergovernmental Relations’, Public Administration Review, 2006, p. 663-676.

45Dillman (D.), Mail and internet surveys: The tailored design method, New York, J. Wiley, 2000.

46Dodd (W. E.), ‘The Principle of Instructing United States Senators’, South Atlantic Quarterly, vol. 1, 1902, p. 326-332.

47Eaton (C.), ‘Southern Senators and the Right of Instruction, 1789-1860’, Journal of Southern History, vol. 18, 1952, p. 303-319.

48Elazar (D. J.), The American partnership: Intergovernmental co-operation in the nineteenth Century United States, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1962.

49Elazar (D. J.), American federalism: A view from the states, New York, Thomas Y. Crowell, 1972, 2e edition.

50Elazar (D. J.), The American constitutional tradition, Lincoln, University of Nebraska Press, 1988.

51Grady (D. O.), ‘Gubernatorial Behavior in State-Federal Relations’, Western Political Quarterly, vol. 40, 1987, p. 305-318.

52Grodzins (M.), The American system: A new view of government in the United States, Chicago, Rand McNally and Company, 1966.

53Haider (D.), When governments come to Washington: Governors, mayors and intergovernmental lobbying, New York, Free Press, 1974.

54Hall (W. K.), The New Institutions of Federalism: The Politics of Intergovernmental Relations, 1960-1985, New York, Peter Lang, 1989.

55Hamilton (M.), ‘The Elusive Safeguards of Federalism’, Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, vol. 574, 2001, p. 93-103.

56Haynes (G. H.), The senate of the United States: Its history and practice, Boston, Houghton Mifflin Company, 1938.

57Hays (R. A.), ‘Intergovernmental Lobbying: Toward and Understanding of Issue Priorities’, Western Political Quarterly, vol. 44, 1991, p. 1081-1098.

58Hoffman (W. S.), ‘Willie P. Mangum and the Whig Revival of the Doctrine of Instructions’, Journal of Southern History, vol. 22, 1956, p. 338-354.

59Jensen (J.), ‘More than Just Money: Why Some (But Not All) States Have a Branch Office in Washington’, Paper Presented at the 2010 Annual Meeting of the Midwest Political Science Association, Chicago, April 22, 2010.

60Jensen (J.) and Emery (J. K.), ‘The First State Lobbyists: State Offices in Washington During World War II’, The Journal of Policy History, vol. 23, 2011, p. 117-149.

61Kincaid (J.), ‘From Cooperative to Coercive Federalism’, Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, vol. 509, 1990, p. 139-152.

62Kramer (L. D.), ‘Putting the Politics Back into the Political Safeguards of Federalism’, Columbia Law Review, vol. 100, 2000, p. 215-293.

63Leckrone (J.) and Gollob (J.), ‘Telegrams to Washington: Using Memorials to Congress as a Measure of State Attention to the Federal Policy Agenda’, State and Local Government Review, vol. 42, 2010, p. 235-245.

64Lutz (D. S.), The origins of American constitutionalism, Baton Rouge, Louisiana State University Press, 1988.

65McGuire (M.), ‘Intergovernmental Management: A View from the Bottom’, Public Administration Review, 2006, p. 677-679.

66McPherson (E. C), ‘The Southern States and the Reporting of the Senate Debates, 1789-1802’, The Journal of Southern History, vol. 12, 1946, p. 223-246.

67Madison (J.), Federalist Papers 10, 37 and 51, in SCHECHTER (S. L.), Roots of the republic: American founding documents interpreted, Madison, Madison House, 1990, p. 309-323 and p. 330-334.

68Marbach (J.) and Leckrone (J. W.), ‘Intergovernmental Lobbying for the Passage of TEA-21’, Publius: The Journal of Federalism, vol. 32, 2002, p. 45-65.

69Munroe (J. A.), ‘Nonresident Representation in the Continental Congress: The Delaware Delegation of 1782’, The William and Mary Quarterly, vol. 9, 1952, p. 166-190.

70Nice (D. C.) ‘State Support for Constitutional Balanced Budget Requirements’, Journal of Politics, vol. 48, 1986, p. 134-142.

71Nugent (J. D.), Safeguarding Federalism: How States Protect Their Interests in National Policymaking, Norman, University of Oklahoma Press, 2009.

72Pelissero (J. P.) and England (R. E.), ‘State and Local Governments’ Washington ‘Reps’ – Lobbying Strategies and President Reagan’s new Federalism’, State and Local Government Review, 1987, p. 68-72.

73Pittenger (J. C.), 'Garcia’ and the Political Safeguards of Federalism: Is There a Better Solution to the Conundrum of the Tenth Amendment?’, Publius: The Journal of Federalism, vol. 22, 1992, p. 1-19.

74Posner (P.), The politics of unfunded mandates, Washington, DC, Georgetown University Press, 1998.

75Regan (P. M.) and Deering (C. J.), ‘State Opposition to REAL ID’, Publius: The Journal of Federalism, vol. 39, 2009, p. 476-505.

76Riker (W. H.), ‘The Senate and American Federalism’, American Political Science Review, vol. 49, 1955, p. 452-469.

77Schattschneider (E. E.), The Semi-sovereign People: A Realist’s View of Democracy in America, Wadsworth Publishing, 1960.

78Schwartz (H.), ‘The Supreme Court’s Federalism: Fig Leaf for Conservatives’, Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, vol. 574, 2011, p. 119-131.

79Smith (T. E.), When states lobby, Ph.D. Dissertation, State University of New York at Albany, 1998.

80Squire (P.) and Hamm (K. E.), 101 Chambers: Congress, Senate Legislatures, and the Future of Legislative Studies, Columbus, The Ohio State University Press, 2005.

81U.S. Supreme Court, ‘Garcia v. San Antonio Metropolitan Transit Authority, 469 U.S. 528’, in Foster (J. C.) and Leeson (S. M.), Constitutional law: Cases in context, vol. I, Upper Saddle River, Prentice Hall, 1998.

82Volden (C.), ‘Intergovernmental Political Competition in American Federalism”, American Journal of Political Science, vol. 49, 2005, p. 327-342.

83Zimmerman (J. F.), Contemporary American federalism: The growth of national power, Westport, Praeger Publishers, 1992.

84Zimmerman (J. F.) ‘National-State Relations: Cooperative Federalism in the Twentieth Century’, Publius: The Journal of Federalism, vol. 31, 2001, p. 15-30.

Notes

Para citar este artículo

Acerca de: Justin Gollob

Assistant Professor, Phd, Department of Political Science, Colorado Mesa University

Acerca de: J. Wesley Leckrone

Assistant Professor, Phd, Department of Political Science, Widener University