- Home

- Volume 15 : 2015

- The Management of Immigration Related Cultural Div...

- Australian Strategic Approaches to Managing National and State Diversity

View(s): 20565 (478 ULiège)

Download(s): 0 (0 ULiège)

Australian Strategic Approaches to Managing National and State Diversity

Abstract

Australia is a global exemplar of nation-building through government planned and administered skilled, family and humanitarian migration programs. By 2011 26% of the population were immigrants, at a time when extraordinary linguistic, religious, racial and cultural diversity were evident. The federal government’s role since the 1901 establishment of the Commonwealth of Australia has spanned migration policy formation, selection, admission, compliance and naturalization functions. The settlement responsibilities of the eight state and territory governments have also grown – a process facilitated by generally amicable federal – subnational relations. Within this context this article describes contemporary Australian approaches to managing linguistic, religious and artistic diversity, comparing federal and state government roles in a period associated with significant multicultural challenges.

Table of content

1. The Australian Immigration Context

1.1 The Immigration Context - Federal and State Roles

1Australia is a global exemplar of nation-building through government planned and administered skilled, family and humanitarian migration programs. By 2006 it had the world’s highest percentage of foreign-born (24%, with 44% of Australians either immigrants or the children of immigrants), followed by New Zealand (23%), Canada (20%) and the United States (11%). Population growth has continued unabated since. By 2011 26% of the population was overseas-born, fuelled by net annual gains of up to 400,000 people. Australia’s migration target for 2014-2015 was set at 218,000 permanent residents (spanning migrants and refugees). In addition to these arrivals, the government admitted large numbers of long-stay temporary migrants – many of whom are likely to category-switch and stay. By 2014-15 Australia operated five key immigration pathways:

-

Skilled: Two-thirds of permanent places were allocated to skilled migrants, selected on the basis of human capital attributes to contribute to Australia’s future economic development (128,550 places in 2014-2015 compared to 20,210 in 1994-95).

-

Family and humanitarian: An additional 60,885 permanent migrants were admitted under the family category (compared to 37,078 in 1994-1995). A further 13-18,000 humanitarian migrants would be selected (the great majority from offshore rather than as direct flight orboat arrivals).

-

Temporary foreign workers: Up to 130,000 temporary foreign workers are also annually resident, selected by employers to work in under-supplied sectors or sites for up to four years, through Australia’s highly deregulated temporary entry program (negligible numbers of temporary workers were admitted in 1994-95).

-

International students: Further 526,932 international students were enrolled in Australia in2015 (compared to around 87,000 in 1993-1994)1. A third will ultimately stay – like temporary foreign workers converting to skilled migrant status.

2The federal government’s role since the establishment of the Commonwealth of Australia in 1901 has spanned migration policy formation, selection, admission, compliance and naturalization functions. Increasingly it has also funded settlement services in the past 60 years, delivered by subnational authorities. The migration responsibilities of Australia’s eight state and territory governments have also grown, with a strong social and economic integration focus.Few debates on migration, multiculturalism and Indigenous affairs have concerned federalism to date, despite frequent challenges to Commonwealth dominance in the contested jurisdictions of health, education and tax (with calls for “reform of the distribution of powers and the financial arrangements of the federation”). The federal government is deemed to be a “unifying migration and settlement force”, in a context where:

… local politics is typically concerned with matters such as the maintenance of local roads and services; state politics is usually concerned with matters such as education, hospitals and policing; and federal politics is largely concerned with matters such as economic management, taxation, social services, and international affairs2.

1.2 The Evolution of Australian Multicultural Policy

3According to Hawthorne, in the first global study to compare federal and state roles in relation to immigration and integration, Australia embarked on a mass post-war immigration program in 1946 following decades of sustained (predominantly British) intakes3. The White Australia Policy, introduced through the Immigration Restriction Act in 1901, was maintained until 1973 as a bar to Asian and other “coloured” migration4. From 1945 to 2012, 7 million people were admitted as settlers, including 185,099 arriving in the peak year of 1969-70. Migration from the United Kingdom (UK) was first prioritised, along with the selection of ex-service personnel and resistance fighters from Europe. Initiating Australia’s commitment to humanitarian entry, agreements were reached with the International Refugee Office to settle a minimum of 12,000 displaced Europeans a year, resulting in 170,000 East European arrivals between 1947 and 19545. By the 1950s and 1960s the Netherlands, Germany, Italy, Greece, Turkey and Yugoslavia had also emerged as key migration sources, triggered by domestic political and/or economic events. Major intakes of Hungarian (1956), Czech (1968) and Chilean (1973) refugees followed, with sustained flows from Vietnam occurring from 1975 (constituting a 300,000+ minority by 2015). Migration to Australia has reflected virtually every geopolitical event since, in a context where a policy of multiculturalism was foreshadowed in 1973, adopted from 1978, and immigration became non-discriminatory and truly global6.

4From its inception the Australian government prioritised three multicultural policy priorities, as follows:

Cultural identity: The right of all Australians, within carefully defined limits, to express and share their individual cultural heritage, including their language and religion.

Social justice: The right of all Australians to equality of treatment and opportunity, and the removal of barriers of race, ethnicity, culture, religion, language, gender or place of birth.

Economic efficiency: The need to maintain, develop and utilise effectively the skills and talents of all Australians, regardless of background7.

5In 1989 a National Agenda for a Multicultural Australia was established, following extensive national consultations. Eight specific goals were endorsed, including “that all Australians should have a commitment to Australia, be able to enjoy the basic right of freedom from discrimination, have equitable access to government resources, and have the opportunity to develop proficiency in English and other languages and share their cultural heritage”8. To achieve such goals, multiple policies were expanded and refined across the next 25 years. These were applied to a wide range of field-specific contexts (including education, employment, health, the law and cultural development). In terms of health, for instance, there was growing Australian demand for the provision of bilingual bicultural care by the 1990s, generated by ethnic organisations in alliance with health policymakers and educators. Key drivers included Australia’s growing cultural and linguistic diversity (with migrants derived from over 200 source countries), limited patient access to translation and interpreter services, and concern at ethnocentrism in “mainstream” health service provision as the population diversified. Reflecting doctors’ and nurses’ position as the “frontline providers” of hospital-based care, calls were made for the recruitment of non-English speaking background (NESB) professionals to service major ethnic communities, in addition to the embedding of transcultural training in medical and allied health degree courses9. Comparable trends were evident across multiple fields, in a context where cross-cultural training courses proliferated in Australia (with over 200 offered by 1996)10.

1.3 The Impact of Changing Immigrant Source Countries on Population Diversity

6By 1994 Australia had a population of 17,849,000 people, including around 380,000 citizens of Indigenous ancestry spanning 50,000 or more years11. In 1994-95 the government admitted a further 87,428 permanent migrants and refugees derived from highly diverse regions. Asia was dominant – the source of 32,376 new migrants, far eclipsing the 25,523 arrivals from Europe:

-

Europe and the former USSR: 25,523

-

South East Asia: 14,861

-

Oceania (principally New Zealand): 13,106

-

North East Asia: 9,899

-

Southern Asia: 7,616

-

Middle East and North Africa: 7,146

-

Africa: 4,857

-

North America: 2,576

-

Southern, Central and Caribbean America: 1,32912

7Australian diversity has escalated rapidly in the decades since. Most notably by 2013 seven of Australia’s top 10 source countries for skilled and family migrants were located in Asia (primarily India, China and the Philippines). Temporary foreign workers were selected from highly developed OECD countries (principally the UK, Ireland, US, Canada and France) in addition to Asia (India, China, the Philippines, Korea and Nepal). Asia was the primary source for international student flows (85% of enrolments), with the top five birthplaces by 2014 China, India, Korea, Vietnam and Brazil. Reflecting contemporary geo-political events, humanitarian migrants in 2012-13 were from the Middle East, Africa and South Asia – primarily Iraq, Afghanistan, Myanmar, Bhutan and the Congo. Direct asylum-seeking arrivals were mostly from Afghanistan, Iran, Sri Lanka, Pakistan and Iraq (see Table 1).

Table 1: Top 10 Countries of Birth for New Persons Granted Visas, by Immigration Category (2012–13)

|

Data |

Permanent (Skilled + Family) |

Permanent (Humanitarian) |

Temporary Foreign Workers |

International Students |

|

Total |

189,158 2012-13 |

20,019 2012-13 |

98,570 2013-14 |

259,278 2012-13 |

|

Category |

Skilled: 128,973 Family: 60,185 |

Offshore: 12,515 Onshore: 7,504 |

457 long-stay visa |

International student visas |

|

Top sources |

2012-13: India (40,051) China (27,334) UK (21,711) Philippines (10,639) S Africa (5,476) Vietnam (5,339) Korea (5,258) Ireland (5,209) Malaysia (5,151) Sri Lanka (4,987) |

2012-13 offshore*: Iraq (4,064) Afghanistan (2,431) Myanmar (2,352) Bhutan (1,023) Congo (489) Iran (471) Somalia (396) Sudan (319) Eritrea (185) Ethiopia (182) |

2013-14: India (24,520) UK (16,710) China (6,160) Ireland (5,950) US (5,720) Philippines (5,470) Korea (2,320) Canada (2,090) France (2,010) Nepal (1,930) |

2012-13: China (54,015) India (24,808) Korea (12,942) Vietnam (10,725) Brazil (10,682) Thailand (9,274) Malaysia (9,143) Saudia Arabia (8,084) Indonesia (8,060) US (7,598) |

Sources: Adapted from a wide range of Department of Immigration and Citizenship and Department of Border Protection 2013-14 reports listed in References13.

1.4 Recent Pressures on Australian Multiculturalism – 2001-2014

8Within this fast changing demographic context, successive Australian governments have maintained bipartisan support for mass migration and population growth. They have continually championed the value of ethnic, linguistic and religious diversity. At the same time, since the attack on the New York World Trade Towers in September 2001 the tenor of public debate concerning multiculturalism has changed (in line with recent trends in Europe and North America)14. Australian soldiers have engaged in wars in Afghanistan (continuing) and Iraq, as a key ally in the United States “Coalition of the Willing”. Perceptions of multiculturalism have been tainted by successive events in the Middle East, by the 2002 Bali bombings (where Australian tourists were targeted and 88 killed), and by the perceived risk of “home-grown terrorism” (exacerbated by the Sydney siege in December 2014, where hostages were taken captive by a former Iranian asylum-seeker). Such developments have coincided with unprecedented growth in Islamic migration - most notably the escalating number of undocumented “illegal maritime arrivals” (IMAs) brought to the Australian coast by people-smugglers15. In 2008-09 just 678 IMAs applied for asylum in Australia. This rose to 18,119 in 2012-13 – polarising national debate and triggering the adoption of punitive bipartisan measures (ranging from the mandatory detention of IMAs to the excision of select Australian offshore territories).

9In 2013 Australia’s conservative Liberal-National parties fought the federal election on three key platforms: migration (“stopping the boats”); fiscal contraction (removal of the national deficit), and abolition of environmental controls (the previous government’s emissions reduction scheme). Following their resounding victory, the federal Department of Immigration and Citizenship was re-named the Department of Immigration and Border Protection (DIBP) – its emphasis for the first time squarely placed on compliance functions. The Department’s 2013-14 Annual Report stated the government’s priorities in the period ahead were to “enhance Australia’s national security, economy and society, through effective border protection, targeted temporary and permanent migration, and humanitarian and citizenship programmes”16.

10In global terms Australia represents an outstandingly tolerant society, like the US and Canada. In recent decades it has absorbed an extraordinary level of cultural, racial and religious diversity with remarkably little backlash. Despite this, the case studies to follow explore select aspects of Australian multiculturalism at a time of growing policy tension. Emphasis is placed on the federal government’s role, compared to select subnational initiatives. Close to 80% of Australia’s population live in just three states: New South Wales (32%), Victoria (25%) and Queensland (20%). By 2011 Victoria was the top settlement site for migrants (home to 29% of the foreign-born), followed by NSW (28%), and Queensland (23%), noting these states have attracted very diverse streams. (See Table 2.)

Table 2: Top Source Countries for New Migrants, New South Wales, Victoria and Queensland (2012-13)

|

Migrants to NSW |

Total Arrivals |

Migrants to Victoria |

Total Arrivals |

Migrants to Queensland |

Total Arrivals |

|

India |

11,856 |

India |

10 568 |

New Zealand |

9 469 |

|

China |

10,397 |

China |

8 985 |

India |

4 511 |

|

UK |

6,426 |

New Zealand |

6 281 |

UK |

4 179 |

|

New Zealand |

5,246 |

UK |

4 192 |

China |

2 828 |

|

Philippines |

2,899 |

Sri Lanka |

2 554 |

Philippines |

2 438 |

|

Iraq |

2,498 |

Malaysia |

2 012 |

South Africa |

1 865 |

|

Korea |

2,231 |

Vietnam |

1 957 |

Korea1 |

1 115 |

|

Vietnam |

1,951 |

Philippines |

1 942 |

Vietnam |

1 071 |

|

Nepal |

1,913 |

Afghanistan |

1 520 |

Sri Lanka |

751 |

|

South Africa |

1,747 |

Pakistan |

1 426 |

Ireland |

705 |

|

Other |

28,799 |

Other |

22 085 |

Other |

15 243 |

|

Total |

76,196 |

Total1 |

63 738 |

Total2 |

44 338 |

Source: Adapted from Department of Immigration and Border Protection, Migration to Australia’s States and Territories 2012-13, Canberra, 2014, Tables 18, 24 and 30, p.26, 36, 46.

1.5 State Compared to Federal Roles in Immigrant Integration

11State governments have a major commitment to facilitating migrants’ social and employment integration, as is the case in Canada17.The case studies to follow reference activities in the key states of NSW, Victoria and Queensland, which have developed dedicated multicultural structures. New South Wales, for example, established an Ethnic Affairs Council in 1975 followed by an Ethnic Affairs Commission. Its landmark Ethnic Affairs Policy Statement in 1983 was designed to achieve “systemic reform and change the attitudes of the bureaucracy towards the provision of services to better meet the needs of a diverse population”. Hailed as world best practice and a “cornerstone” of effective public sector practice, this policy first focused on welfare and equity, followed (from the 1990s) by sustained championing of cultural diversity “as an economic and social resource”18.By 1993 ethnic affairs had become a stand-alone ministry in NSW, with 200 government departments and agencies required to report on multicultural initiatives. In 2000 this was extended to 160 local councils following establishment of the Community Relations Commission and Principles of Multiculturalism Act. Major hospitals and corporatized bodies were included, based on a constantly broadened definition of public authorities and strong accountability requirements. The state’s Charter of Principles for a Culturally Diverse Society defined the following rights-based framework:

1. All individuals in NSW should have the greatest possible opportunity to contribute to, and participate in, all levels of public life.

2. All individuals and public institutions should respect and accommodate the culture, language and religion of others within an Australian legal institutional framework where English is the primary language.

3. All individuals should have the greatest possible opportunity to make use of and participate in relevant activities and programs provided and/or administered by NSW Government institutions.

4. All NSW public institutions should recognize the linguistic and cultural assets in the NSW population as a valuable resource and utilize and promote this resource to maximize the development of the state19.

12To achieve national migration goals the Australian government has also made a sustained investment in settlement services. The aim is to facilitate the socio-economic integration of non-British migrants, aligned with state-based initiatives. A range of such initiatives represent world best practice, despite inevitable fiscal limits20. Following Australia’s visionary 1978 and 1981 Galbally reviews of multiculturalism, their aim is transitional support, stressing “the self-help nature of minority communities, in areas such as welfare, language maintenance, and religious identification”, with public institutions expected “only to support, not carry or implement, many of these initiatives”21. A wide range of measures are involved, including Australia’s innovative multilingual Special Broadcasting Services, designed to address the linguistic, cultural and ethno-specific needs of immigrant Australians at multiple stages of the life cycle. All states/territories are deeply engaged in these processes. In Victoria, for instance, initiatives include multicultural policing, aged care, a highly specialised health interpreter service, strategies to facilitate foreign credential recognition, and field-specific labour market integration programs.

13The federal government supports such processes through substantial fiscal powers (collecting 60-75% of total revenue compared to 45% by federal governments in Canada and Switzerland and 54% in the US). Integration services are largely managed by state governments with federal funding support22.In 2008-09 the Immigration Department’s budget allocation included $A 275,925,000 in outlays for migrant settlement, citizenship and social cohesion programs, in addition to $A 190,581,000 for program management and compliance23.In 2013-14 the Department reported spending $A 1,575,610,000 on the “net cost of services”, including $A 62,442,000 for integration grants to non-profit organisations24. In 2014-15 Australia’s budget for settlement services was set at $A 65,059,000, to facilitate the “equitable economic and social participation of migrants and refugees”. Much was allocated to English language training, and the provision of free interpreting services (with 1.4 million phone and 81,823 on-site services delivered free the previous year). Further federal funding is channelled through external federal and state/territory portfolios – including education, employment, health and arts departments. Four major service provision models currently dominate in Australia:

-

Mainstream – For example social security benefits delivered to unemployed migrants through the federal employment and education ministry.

-

Migrant-specific – For example the Adult Migrant English Program (AMEP), delivered on-arrival and followed by employment-related English training.

-

Category-specific– For example catering to the needs of refugees, such as Melbourne and Sydney-based services addressing the mental and physical needs of survivors of torture and trauma.

-

Ethno-specific– Programs delivered through ethnic community grants, for example to support leadership and program development, such as the establishment of ethno-specific women’s refuges, crèche services, tutoring services for refugee youth etc.

2. Linguistic Diversity and Development of English Skills

2.1 Australia’s Language Policy

14As is clear from the above, Australia has long been characterised by extraordinary linguistic diversity. At the time of first British settlement in 1788, the Indigenous population spoke an estimated 350-750 languages/dialects, declining to fewer than 150 in daily use by 201125. Migration has since transformed the range of community languages used, with the right to language maintenance constituting a core plank of Australian multiculturalism. To support this process, the federal government in 1988 promulgated a National Policy on Languages, defining four rationales for second language learning and maintenance: Enrichment (cultural and intellectual), Economics (foreign trade and vocations), Equality (social justice and overcoming disadvantages) and External (Australia’s role in the region and the world). Two such principles are worth quoting at length, to illustrate the direction of policy:

-

Equity and cohesion value: Action taken as a result of the national language policy will emphasise the need for social and national cohesion in Australia while simultaneously recognising the diversity of the society and the inherent benefits of this diversity. Australia has adopted policies of multiculturalism i.e. equity for all community groups and cultural diversity within national cohesion and unity…

-

Geo-political value: Australia’s geographical proximity in the Asian/ Pacific/ Indian Ocean region to countries which use languages other than English carries specific implications for a national languages policy... Australia’s economic, trade, diplomatic, intellectual, cultural, political and security interests require that a large pool of Australians gain skilled and proficient knowledge of the languages of our region and world languages26.

15According to a 1991 review of linguistic diversity conducted by Clyne, Australia gathered no statistical data on language use until the 1976 Census. Following this, data on the top 14 languages were first secured: English, Italian, Greek, German, Serbo-Croatian, French, Dutch, Polish, Arabic, Spanish. Maltese and “Aboriginal” (with multiple Indigenous languages conflated to one)27. Vast numbers of immigrants at this time spoke languages other than English (LOTE) at home, most notably 17% of the population in Victoria, 12% in NSW and 6% in Queensland. A decade later Australia’s “face of multilingualism” had changed – led by growth in the use of Chinese and Filipino languages, Arabic, Vietnamese and Indonesian-Malay (compared to growth in just one European language – Macedonian). The majority of Arabic speakers at this time were Christians from Lebanon or Egypt, while Chinese language speakers were principally derived from Singapore and Hong Kong. These patterns were set to change following new Asian, Middle Eastern and African migrations28. According to a German analyst, by 2004 Australia was characterised by “many voices: ethnic Englishes, Indigenous and migrant languages”29. In 2011 the primary languages beyond English spoken at home were Mandarin (336,409 speakers), Italian (299,833), Arabic (287,175), Cantonese (263,674), Greek (252,217) and Vietnamese (233,390). Tongues experiencing the fastest growth were spoken by recent Asian and African migrants, with 16 of the top 30 areas for second language use in NSW and 12 in Victoria30.

2.2 Australia’s Investment in English Language Training

16A wide range of linguists have described Australia’s community language diversity. Less attention has been paid to trends in relation to English – the level of Australian investment in training, along with growing implementation of language testing to foster social cohesion31.

17Australia’s federal government has made sustained investment in English training for recently arrived migrants for decades. The Adult Migrant English Program commenced with “shipboard English” in the late 1940s, a service since vastly professionalized and expanded32. By 1991 the AMEP was the largest government-funded adult English language teaching program in the world, and an example of global best practice. “Learner pathways” were designed at first point of contact, to guide migrants from acquisition of basic English to achieve employment or study goals supported by federally funded training33. In 2012-2013 the AMEP provided tuition and services through 27 contracts to more than 59,754 clients from 188 countries and 252 language groups – with the top three source countries at this time China, Afghanistan and Vietnam. Classes were held in 274 locations, most delivered by subnational not-for-profit agencies. The program reached 52% of new migrants, facilitated by counselling services delivered to 64,000 clients that year. Migrants lacking functional English are entitled to receive up to 510 hours of English tuition in the first 5 years post-arrival or “the number of hours it takes to reach functional English (whatever comes first)”, with the average client receiving 369 hours of teaching34. Following this, the settlement language pathways to employment and training program delivered eligible migrants an additional 200 hours of English tuition, including up to 80 hours of work experience. 2,639 migrants participated in this program in 2012-2013, focused on “understand(ing) Australian workplace culture and practices, work ethics, employment processes, occupation health and safety, and taxation requirements”35. State governments contributed additional funds, within ethnic affairs policy frameworks. Comparable initiatives existed at the school level to cater to child migrants, including intensive support for at-risk groups (for example unaccompanied refugee minors).

2.3 Australia’s Recent Expansion of Language Testing

18Beyond English language teaching, it is important to note the past decade has coincided with rapid growth in the use of English language testing, with profound social and economic impacts. English testing has been used as a tool to determine “bona fide” refugees, as the government grapples to contain the scale of “illegal maritime arrivals” (onshore asylum seekers)36. It has become a filter for citizenship, as in the UK, the USA, Canada and the Netherlands. An English language and values test was introduced with bipartisan support in 2007 to screen applicants, reflecting the view that “a coherent set of national values” would “help protect Australia in… uncertain times”37. The government’s aim is to “encourage prospective citizens to… support successful integration into Australian society… to demonstrate in an objective way that they have the required knowledge of Australia, including the responsibilities and privileges of citizenship, and a basic knowledge and comprehension of English”38. In 2010 99% of skilled category applicants passed the test on their first or subsequent attempts, compared to 94% of family migrants, but just 79% of refugees (typically derived from the Middle East, Asia and Africa). By 2012-2013 98% of applicants passed the test, and in 2013-14, 213,885 migrants applied, of whom 83% were approved.

19Beyond access to citizenship, English language testing has increasingly been used to determine the entry of skilled migrants. IELTS (the International English Language Testing System) and TOEFL (the Test of English as a Foreign Language) have been the dominant instruments to date, with high life stakes for candidates. There is a strong empirical rationale for this policy. A series of reports from the 1980s demonstrated poor English to triple the unemployment risk for migrant males, while doubling it for females, representing “an awesome and devastating barrier” at every stage of the employment life cycle in Australia39.From 1993 the federal government mandated English testing for skilled principal applicants, commencing with 114 “Occupations Requiring English” (since extended to all fields). To be eligible to migrate, applicants were required to prove they possessed “vocational” English – a process markedly favouring native English speakers.

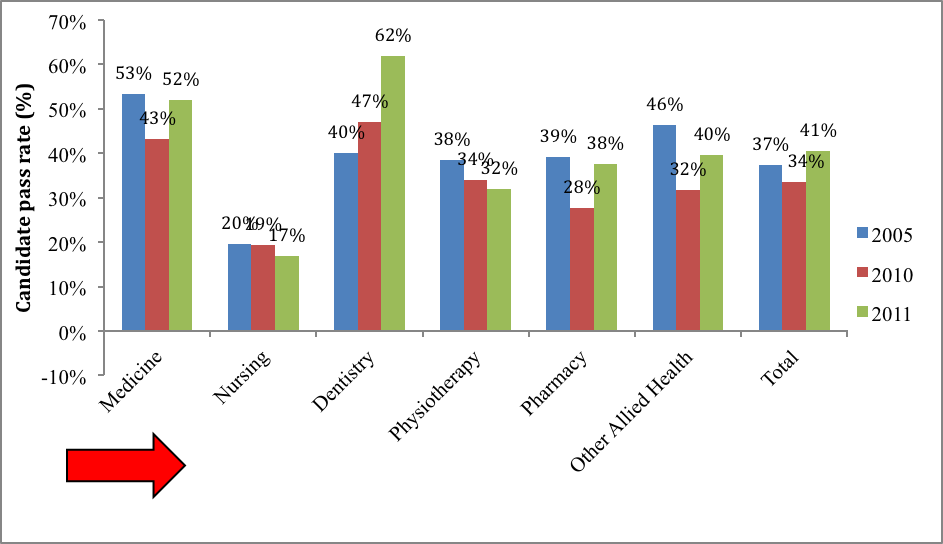

20The impact of English testing on skilled migrant selection has intensified since. In 2010-2012 the Immigration Department reviewed selection procedures, to maximise selection of migrants “with the high value, nation-building skills that are needed by the Australian economy and labour market”40.Impacts have been profound, although it is important to note testing English (as demonstrated) has not reduced immigrant diversity. Instead, testing filters primary applicants to select non-native speakers characterised by advanced levels of English.By 2011, for example, 62% of dental applicants passed the health-specific Occupational English Test on their first or subsequent attempt, compared to 52% of doctors, 38% of pharmacists but just 17% of nurses (with candidates from the Philippines and Japan performing poorly)41 (see Figure 1). From July 2012 skilled category applicants with native or near-native English ability were awarded the highest migration points (with close to a third of the points required allocated to applicants scoring IELTS Band 8 or above). Comparable strategies prevail in other immigrant-receiving countries, such as New Zealand and Canada. Along with employment social cohesion is a major motive. The government seeks to enhance host country language ability, in order to minimise ethnic separatism at a time of growing linguistic and racial diversity.

Figure 1: Impact of English Language Testing on Migrant Health Professionals by Major Field (2005-2011)

Source: Hawthorne (L.), Health Workforce Migration to Australia – Policy Trends and Outcomes 2004-2010, Health Workforce Australia, Adelaide, 2013, http://www.hwa.gov.au/work-programs/international-health-professionals/health-profession-migration.

3. Religious Diversity and the Promotion of “Harmony”

3.1 The Right to Freedom of Belief in Australia

21Australia’s multicultural policy strongly affirms the right to freedom of religion and belief, in addition to language maintenance. According to a seminal study, “As a result of immigration patterns over the last quarter century, (the nation’s) religious mosaic has changed forever… Australia has welcomed an increasingly diverse group of migrants from a wide range of national origins, cultural backgrounds, and religious orientations”. Most notably by 1994:

… the past 25 years have seen the emergence of a significant Muslim presence in Australia with the settlement of immigrants from Turkey, Lebanon, other countries in the Middle East and Asia…. Nearly 1 per cent of the Australian population now indicates Islam as their religion. Muslims are the largest non-Christian religious group in Australia… (w)ith 35 per cent of Australian Muslims indicating that they were born in Australia… This community is strongest in Sydney and Melbourne. It is a youthful community which is making its way into the workforce, educating its children in both State and increasingly private Muslim schools, and establishing the social and community structures to support the Muslim way of life in this country42.

22Australia’s federally funded Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission made the right to religious freedom the focus of its first Discussion Paper in 1997. Affirming international human rights instruments, the Commission’s priorities included prevention of discrimination on the grounds of religion in employment; in public life; in planning and environment laws; reduced risk of violence, intimidation and harassment; the right to preserve Indigenous beliefs; and the necessity of supporting religious freedom with appropriate legislation43.

23By 2011 Australia included 136 religion categories, despite a fifth of the population professing no faith. Christianity predominated (61%), with the main denominations Catholicism (5,439,268) and Anglicanism (3,679,906). The speed of change and the growth of Islam at this time however were emerging as critical issues. The next largest religions were Buddhism (with 528,976 believers or 2.5% of the population), Islam (476,291 or 2.2%), Hinduism (275,533) and Judaism (97,335). Between 2006 and 2011 the fastest growing faiths were Hinduism (+86%), Islam (+40%) and Buddhism (+26%). While the government maintains a celebratory approach to religious diversity, and co-funds ethnic schools, in the past decade a deep wariness has emerged in relation to potential Islamic separatism. A late 2014 survey found “An increasing number of Victorians believe there are ethnic or racial groups in Australia who do not “fit in”, despite most saying they are in favour of cultural diversity”. Respondents most likely to express “prejudiced attitudes” felt negative towards Muslims (22%), people from the Middle East (14%), Africans (11%) and refugees (11%), in a context where Islam was the religion of most of these new migrants44.

3.2 Contemporary Concern – Growth in Islamic Migration

24Australian concern for “Islamicisation” has been expressed in multiple ways in recent years, including the following:

-

Asylum-seekers: Community support for punitive bipartisan measures designed to “stop the boats”, and minimise the direct arrival of asylum seekers in Australia.

-

Religious leaders: Steps taken to minimise the importation of imams trained overseas who are perceived as lacking “Australian values”, plus initiatives to monitor and re-train “conservative” resident imams.

-

Islamic schools: Concern for ethno-centrism, separatism and potential political proselytizing at Muslim schools, including their exclusion of mainstream teaching staff.

-

Mosques: Opposition to the establishment of new mosques, including in regional sites – typically couched as a desire to minimise noise and “street traffic”.

-

Dress: Consideration given to barring women from wearing the hijab in national parliament, or when testifying in courts of law (defeated).

-

Dress: Consideration given barring women from wearing the hijab in national parliament, or when testifying in courts of law.

-

Racial vilification: The conservative government’s 2014 attempt to weaken Australia’s racial vilification laws (abandoned mid-year following widespread concern from “multicultural and Aboriginal communities… the legal profession, human rights experts, psychologists and public health professionals”, in the context of Australia’s “emphatic affirmation of… commitment to racial tolerance”)45.

-

Festivals: Contestation of “political correctness” in education sites – for example kindergartens and schools barring the celebration of Christmas or Easter to avoid giving offence to “other faiths”.

25Examples of significant unrest in Australia are few, despite individual acts of aggression, abuse and discrimination (for example targeting women wearing the hijab). This process is not left to chance however. The federal government makes a major policy investment in the promotion of civic “harmony”, with states playing a key integration role. Their scope is large – focused on new immigrants but also second generation youth “grappling with issues of identity and participation [and] young people of all backgrounds… creating their own dynamic brand of Australian multiculturalism”46. The focus is migrants but also mainstream society.

26In 2005, for instance, race riots between Lebanese and Australian youth erupted on a popular Sydney surfing beach (Cronulla), confronting “national and international audiences with reports of alcohol-fuelled violence against people of “Middle-Eastern appearance” by demonstrators clad in Australian flags, and violent reprisal attacks that followed”47. State-specific integration initiatives swung into action, backed by the Council of Australian Governments’ National Action to Build on Social Cohesion, Harmony and Security48. Multiple youth-focused programs were developed in the following years, including leadership training, outreach to Muslim Australians (42 community projects by 2010 to facilitate interaction between Muslim and non-Muslim youth), inter-faith initiatives, school-based support and ethnic community capacity-building. For example aspecial outreach program was established for young Australians of Middle Eastern origin to encourage them train with local youth as surf lifesavers. Pro-active initiatives exist across most states. Victoria, for example, provides support for around 700 multicultural festivals per year to promote inter-ethnic engagement. It delivers a vast array of additional programs, and funds migrant organisation infrastructure49.

27Despite recent tension, spontaneous public goodwill is frequently evident. Most recently, in December 2014, a former Iranian asylum seeker in Sydney took multiple hostages in a Lindt café. Two died, in a context where dual responses were immediately evident. Within hours of the siege a social media campaign had sprung into life generated by young Australians. Affirming solidarity and support for local Muslims, 300,000 followers signed on to an “I’ll Ride With You” campaign in its first day. At the same time however, Australia’s most prominent tabloid columnist highlighted the perceived danger of Islamic extremism relative to other immigrant faiths:

Islamic groups claimed nothing in their faith licensed this ghastly attack… Except, of course, we rarely get damaged individuals killing people in chocolate shops in the name of Buddha. We don’t get damaged individuals beheading a British soldier in the name of Christ. We don’t get damaged individuals shooting a Canadian soldier guarding Canada’s Cenotaph… or trying to blow up jets with explosives in their shoes or underwear in the name of any faith other than Islam… Must we always feign this surprise when a terrorist is found to be – gasp – Muslim? Surely we can finally drop this absurd game given that 21 of the 21 people jailed for terrorism offences here in the past couple of decades were Muslim, as are 19 of the 20 proscribed terrorist groups in Australia50.

28Australian federal and state governments continue to address these issues. They invest major sums in facilitating multicultural “harmony”, including attempts to minimise Islamic marginalisation. Fear drives many such programs. In 2014-15 the federal government spent $A13 million “on education, youth activities and employment programs for young Muslims at risk of becoming radical jihadists”, as part of its $A630 million counter-terrorism package. This was dramatically upgraded in 2015 with $22 million to be spent ‘fighting terrorist propaganda, which is used by organisations like Islamic State to recruit young Australians through the internet and social media’5152. At the same time opinion polls suggest local Muslims feel increasingly and unfairly targeted53.

4. Artistic Diversity and Media Representation

4.1 National and State Cultural Policies and Initiatives

29Finally, it is worth briefly examining measures designed to support artistic diversity in Australia – focused in this instance on the use of multicultural arts as a key integration strategy, compared to ongoing challenges related to media representation.

30Australia’s Creative Nation policy was promulgated two decades back by a Labor government (1994). The aim was to provide cultural leadership, including support for diversity in relation to the arts. Australia supports the UNESCO Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions, including “access, participation and celebration of the Arts in their diverse forms (as) a human right”. National and state arts policies have proliferated in recent decades - designed to reach and engage with diverse ethnic groups, through initiatives enacted at federal, state and local levels. Since 2006 the Australia Council for the Arts’ multicultural policy has specifically aimed:

311. To increase culturally inclusive leadership by:

32a) ensuring governance is a culturally inclusive process.

b) integrating multicultural aims in each of the Council's activity areas.

c) increasing culturally diverse representation in the arts.

332. To enable the participation in the arts for all Australians by:

34a) delivering specific audience and market development strategies.

b) increasing awareness of and access to the Council's programs.

c) brokering and engaging in partnerships.

353. To support the development of creative content which reflects a multicultural Australia by:

36a) encouraging cultural inclusiveness.

b) supporting multicultural arts industry infrastructure.

c) supporting content development.

d) encouraging creativity which spans the spectrum of tradition and innovation.

374. To encourage creative interfaces between Indigenous and non-English speaking background artists by facilitating cultural exchanges54.

38The Brisbane Multicultural Arts Centre, for instance, is “the lead agency in Queensland for the development, presentation, promotion and advocacy of arts by migrant and refugee artists and their communities in Queensland”, supported by a 24 year history. The Centre is active statewide, affirming the contribution of diverse communities to Australian cultural life, with the aim of facilitating “a richer and more vibrant cultural life for all Queenslanders”. In terms of policy, the Centre is aligned with the Ethnic Communities Council Queensland, the Multicultural Development Association, and a wide range of additional state or regional bodies. The Multicultural Development Association (for example) is a lead Brisbane employment and advocacy organisation designed to support migrants and refugees, including through cultural arts events with a capacity to attract “large crowds and media interest”. Supported by federal government funding it employs 90 permanent staff, 200 cultural support workers, and an extensive volunteer network. Despite this, concern has been expressed in Queensland that “Across the arts sector, (population) diversity is not adequately reflected in practice or addressed in detail at a policy level. Arts Queensland has no articulated framework, action plan or policy for addressing the specific issues of access, development and leadership in a multicultural context and federally, there is no funding pool attached to the Arts in a Multicultural Australia policy”55.

39Ethnic groups similarly receive significant specialist attention in Victoria, including those who have recently arrived. By 2014 Multicultural Arts Victoria offered a wide range of programs and awards, spanning both visual and performance arts. Initiatives included business training for arts practice, arts and cultural development scholarships for refugee youth, funding for short film development, photographic festivals to celebrate migration and refugees or represent ethno-specific groups, and multiple music performances (for example African drummers and Eritrean bass players). Multicultural Arts Victoria describes itself as “proudly represent(ing) artists and communities from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds… both emerging and established artists and communities from all cultures”. Over 2,000 artists and 800 groups are involved, with their talents showcased to “audiences of 800,000 yearly” (for example at world music cafes)56. At the same time the arts sector is chronically under-funded in all states. There is also often minimal interest in “niche” arts from mainstream Australia.

4.2 Barriers to Media Representation

40In relation to film, television and theatre, racially and culturally diverse actors/ presenters face sustained barriers to achieving media representation and - most critically - employment. Casting barriers can take decades (if ever) to overcome, exacerbated by the notorious precarity and parsimoniousness of Australian arts employment. From the time of its establishment in the late 1970s, Australia’s Special Broadcasting Services (SBS) went beyond blonde, blue-eyed nubile presenters. SBS incorporated first generation and Indigenous Australians from diverse backgrounds. Few such initiatives however were replicated by commercial media. The idealised “face of Australia” remains Caucasian; the spoken voice “accentless”. Exoticism is seldom prized, except for fashion models. The significance of media exclusion for migrants has been documented for decades (as it has for female presenters or actors who reach middle age).

41According to a policy analyst two decades back, ethnic “invisibility” has similarly high stakes. Australia needs to be accurately documented. The media has “a strong role in shaping a sense of nationhood and in creating indentificatory means for the individuals composing the national public”, supported by the production and circulation of “highly affective cultural texts”57. In 1997 an Australia Council report lambasted the typecasting of ethnic actors, as “the taxi driver, the cook and the greengrocer”. Based on widespread media surveys it confirmed migrant Australians to be under-represented in film, theatre and television, with marginalisation:

… particularly pronounced for people of Asian, European and Russian backgrounds… From an artistic viewpoint, there is also evidence that (non English-speaking background) artists are largely restricted to minor, tokenistic or stereotyped roles which fail to offer a broad spectrum of performing opportunities (particularly in) mainstream, commercial or funded theatres.

42Adding insult to injury, “cultural appropriation” was reported to occur – “when culturally specific roles were played by Anglo-Celtic actors” daubed with makeup and false accents58. An analysis of Home and Away, for instance (Australia’s globally successful youth-oriented soap opera), found in the first five years thatthe series offered viewers ethnic invisibility of the highest order – a reassuring pre mass-migration vision of Australia, people by unassailably Anglo characters. The device of centering the series around a succession of fostered children provided an excellent rationale for ethnic exclusion. Two boys, for example, were acknowledged as of Italian and Lebanese descent. By definition each had been abandoned by his natural family, leaving him to identify as 100% “Australian” in terms of language, culture and personal style. Unlike the bulk of Australian country towns, “Summer Bay” lacked an Italian pizza parlour, a Chinese restaurant, or a Greek milk bar. In the program’s first six years just four plotlines focused on “alien” Aboriginal, Yugoslav, Italian and Chinese characters. Each was ruthlessly despatched within a matter of episodes – for example the Chinese girl recalled overseas, the Yugoslav father killed in a plane accident, and the Italian exchange student obliterated by an express train59.

43Despite recent improvements, such findings have been endlessly repeated since, in relation to both the latest immigrant arrivals and Indigenous Australians. According to analysts racial, religious and linguistic marginalisation persists - obscuring the easy everyday ethnic interplay which is mostly the mark of contemporary Australia. Positive signs exist. In 2014 Australia’s second long-running soap series (Neighbours) cast its first Indigenous actor after 30 years60. First and second generation migrants are increasingly prominent as writers, actors and comedians. Australia’s 2014 X Factor was won by a Korean-Australia. However a report that year still called for “colour blind casting” – Actors Equity Australia supporting the US Actors Equity policy of open auditions for all roles, with “final casting reportable to the union”. Indigenous actors stated they fail to be considered for “main stage roles”. An actor of Syrian-Lebanese descent recently reported being “boxed into ethnic roles. I played Indian, Sri Lankan and even an Aborigine once… Now, the more terrorism that happens in the world, I’m only seen for Arab roles, or aggressive characters. I’ve been told I’m the ‘dark option’”61.

44According to a range of analysts, such casting can be socially hazardous. Some warn that the media’s “narrative of ethnic violence” may spur marginalisation, intensifying host societies’ wish “to segregate, isolate, and remove those who might contaminate” in an age of globalisation62.

5. Conclusion

45These are tense issues in contemporary Australian society, at a time when the merits of multiculturalism are being re-appraised. As demonstrated, Australian has absorbed extraordinary numbers of migrants in recent decades, supported by widespread public acceptance. It currently admits around 300,000 migrants per year, on a permanent or long term temporary basis, at a time when 550,000 international students are also resident. Contemporary migrants however are from rapidly changing racial and religious backgrounds. While Asian source countries predominate, in the past decade there have been growing Middle Eastern and African flows, at a time when public debate has been skewed by the World Trade Centre bombings (2001), followed by more than a decade of Australian engagement in Middle Eastern wars and related crises.

46Within this context federal and state governments have intensified their development of multicultural programs to facilitate migrants’ social and economic integration. Community engagement is strong, and there is strong overall takeup. At the same time specific challenges are unquestionably perceived to exist in relation to select Islamic Australians. As noted by a recent conservative analyst (writing in the respected national newspaper, The Australian):

It (now) pays to choose one’s words carefully on the topic of multiculturalism since the penalty for giving offence is high. So let’s just say that the evolution of Australian jihadis – migrants or their offspring who have decided they want to kill us – suggests the multicultural voyage has hit a rocky spot. It’s a pity because in almost every other respect multiculturalism has been brilliant. We’re getting on splendidly, thank you… Australians are more capable of adopting a live-and-let-live attitude than some give them credit for. Yet the intercultural tension between Islam and mainstream Australian values should not be ignored, least of all by institutions such as (Ethnic Community Councils which receive) grants to help maintain the social fabric63.

47The contemporary situation is associated with greater tension than recent decades. A growing number of Muslims, without question, feel stigmatised and marginalised. Despite this pro-active multiculturalism has worked impressively as a policy for Australia for over 40 years. There have been four essential elements to this success: strong political leadership, sustained federal and state government funding, development of multiple sector “niche” initiatives, and ongoing societal monitoring to assess policy effects.

Notes

1 Shu (J.) and Hawthorne (L.), “Asian Student Migration to Australia”, International Migration, vol.XXXIV, n°1, 1996, p.65-87.

2 Aroney (N.), “Australia”, in Moreno (L.) and Colino (C.) (eds), A Global Dialogue on Federalism – Volume 7, Montreal, McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2010, p.27.

3 Hawthorne (L.), “Australia – Federal Compared to State Roles in Immigrant Integration”, in Seidle (L.) and Joppke (C.), Immigrant Integration Policies and Practices: Canada, United States, Australia, Germany, Switzerland, Belgium and Spain, Montreal, McGill-Queen's University Press, 2012.

4 York (B.) (1993), “Admitted: 1901-1946. Immigrants and Others Allowed Into Australia Between 1901 and 1946”, Studies in Australian Ethnic History No 2, Centre for Immigration and Multicultural Studies, Canberra, Australian National University, p.4-6.

5 York (B.) (1993), “Admitted: 1901-1946. Immigrants and Others Allowed Into Australia Between 1901 and 1946”, Studies in Australian Ethnic History No 2, Centre for Immigration and Multicultural Studies, Canberra, Australian National University, p.4-6.

6 Department of Immigration and Citizenship (2009), Fact Sheet 4 – More Than 60 Years of Post-War Immigration, http://www.immi.gov.au/media/fact-sheets/04fifty.htm (accessed on 27/10/2010).

7 Jupp (J.) (ed.), The Challenge of Diversity: Policy Options for a Multicultural Australia, Canberra, Office of Multicultural Affairs, 1989, p.iii.

8 Ibid., p.iv.

9 Hawthorne (L.), Toth (J.) and Hawthorne (G.), “Patient Demand for Bilingual Bicultural Nursing Care”, Journal of Intercultural Studies, vol.21, n°2, p.193-224. For detailed policy case studies see also Reid (J.) and Trompf (P.) (eds.), The Health of Immigrant Australia, Sydney, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1990.

10 Hawthorne (L.) and Zelinka (S.), “The Distinctiveness of Australian Cross-Cultural Training”, Migration Action, vol.XVIII, n°3, 1997, p.3-6.

11 Wikipedia, “Indigenous Australians”, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indigenous_Australians (accessed on 15 December 2014).

12 Bureau of Immigration, Multicultural and Population Research, Settler Arrivals 1994-95, Statistical Report No. 18, Canberra, Statistics Section, 1995.

13 Data derived from Department of Immigration and Citizenship, Australia’s Offshore Humanitarian Program 2012-13, 2013, adapted from Table 14 (p.28); Department of Immigration and Citizenship, Annual Report 2012-13, adapted from Table 15, 2013, p.69; Department of Immigration and Citizenship, “Fact Sheet 60 – Australia’s Refugee and Humanitarian Programme, Figures”, 2013, https://www.immi.gov.au/media/fact-sheets/60refugee.htm#e (accessed on 8/12/2014); Department of Immigration and Citizenship, “Australia’s Humanitarian Program 2013-14 and Beyond”, 2012, adapted from Table 1, http://www.immi.gov.au/media/publications/pdf/humanitarian-program-information-paper-2013-14.pdf (accessed on 8/12/2014)(* source country data only provided for 2011-12 and not with numbers); Department of Immigration and Border Protection, Subclass 457 Quarterly Report, Ending 30 June 2014, 2014, adapted from Table 1.05, p.6.

14 See Kayyali (R.), “The People Perceived as a Threat to Security: Arab Americans Since September 11”, Migration Information Source, July 1 2006; Benton (M.), “Top 10 of 2014 – Issue #6: Governments Fear Return and Intentions of Radicalized Citizens Fighting Abroad” (accessed on 12 December 2014).

15 Department of Immigration and Border Protection, Asylum Trends Australia – 2012-13, Canberra, Australian Government, 2013.

16 Department of Immigration and Border Protection, Canberra, Annual Report 2013-14, 2014, p.10.

17 Siemiatycki (M.) and Triadafilopoulos (T.), “International Perspectives on Immigrant Service Provision”, Toronto, University of Toronto, MOWAT Centre of Policy Innovation, 2010.

18 Whelan (A.), 25 Years of EAPS – Review of EAPS Operation in New South Wales, Sydney, NSW Government, Community Relations Commission, 2009, p.6-14.

19 See NSW Government and Ethnic Affairs Commission, Charter of Principles for a Culturally Diverse Society: Handbook for Chief Executives and Senior Managers, Sydney, NSW Government and Ethnic Affairs Commission, 1995.

20 As demonstrated by successive OECD reports, Australia’s level of investment of host country language training and labour migrant bridging programs was decades in advance of other OECD immigrant-receiving nations, in terms of policy focus and dedicated funding. See for example OECD, Jobs for Immigrants Volume 1 – Labour Market Integration in Australia, Denmark, Germany and Sweden, 2007. See also Hawthorne (L.), “Picking Winners: The Recent Transformation of Australia’s Skill Migration Policy”, International Migration Review, vol.39, n°2, 2005, p.663-696.

21 Lo Bianco (J.), “Multicultural Education in Australia: Evolution, Compromise and Contest”, Singapore, Presentation at International Alliance of Leading Education Institutions Conference, September 2010, p.8.

22 Anderson (G.), Federalism: An Introduction, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2008, p.33-35.

23 Department of Citizenship and Immigration, Annual Report 2009-10, op.cit.,p.36-39.

24 Department of Immigration and Border Protection, Canberra, Annual Report 2013-14, 2014, p.297-218.

25 Wikipedia (2014), “Australian Aboriginal Languages”, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Australian_Aboriginal_languages (accessed on 15 December 2014).

26 Lo Bianco (J.), National Policy on Languages, Commonwealth Department of Education, Canberra, 1988, p.vii, p.6-7.

27 Clyne (M.), Community Languages – The Australian Experience, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1991.

28 Clyne (M.) and Kipp (S.), Pluricentric Languages in an Immigrant Context: Spanish, Arabic and Chinese, Berlin, Mouton de Gruyter, 1999.

29 Leitner (G.), Australia’s Many Voices – Ethnic Englishes, Indigenous and Migrant Languages, Policy and Education, Berlin, Mouton de Gruyter, 2004, p.1.

30 Department of immigration and Border Protection (2014), The People of Australia: Statistics from the 2011 Census, Canberra,Australian Government.

31 Hawthorne (L.), “The Political Dimension of Language Testing in Australia”, Language Testing, vol.14, n°3, 1997, p.248-260.

32 Galbally (F.) et al., Report of the Review of Post-Arrival Programs and Services for Migrants, Canberra, Australian Government Publication Service, 1978.

33 Department of Immigration Local Government and Ethnic Affairs, Adult Migrant English Program – Australia, Canberra,Department of Immigration Local Government and Ethnic Affairs, 1991, p.1-39.

34 Department of Citizenship and Immigration, Annual Report 2009-10, Canberra,p.228.

35 Department of Immigration and Border Protection, “Adult Migrant English Program Administration”, http://www.immi.gov.au/about/reports/annual/2012-13/html/performance/outcome_5/adult_migrant_english_program_administration.htm (accessed on 12/12/ 2014).

36 Eades (D.), Fraser (H.), Siegel (J.), McNamara (T.) and Baker (B.), “Linguistic Identification in the Determination of Nationality: A Preliminary Report”, Language Policy, n°2, 2003, p.182-184.

37 Hardgrave (G.), “Australian Citizenship: Then and Now”, Canberra, Speech to the Sydney Institute, Media Release 7 July 2004, Ministry for Citizenship and Multicultural Affairs, http://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlinfo/search/display/display.w3p:query=ld%3A%22media%2Fpressrel%2FJKBE6%22 (viewed 2/06/2010).

38 Department of Citizenship and Immigration, Annual Report 2009-10, Canberra, 2010, p.244-253.

39 Office of Multicultural Affairs (1989), Towards a National Agenda for a Multicultural Australia - Sharing Our Future, Canberra,Australian Government Publishing Service, p.39.

40 Department of Immigration and Citizenship (2010), “Frequently Asked Questions – New Points Test”, November 1-2, Canberra, p. 2; for detail on this review process see Department of Immigration and Citizenship (2009), “Future Skills: Targeting High Value Skills Through the General Skilled Migration Program – Review of the Migration Occupations in Demand List”, Issues Paper No. 2, September, Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations and Department of Immigration and Citizenship, Canberra; Department of Immigration and Citizenship (2010b), “Review of the General Skilled Migration Points Test – Discussion Paper”, 15 February, Canberra; Department of Immigration and Citizenship (2010c), “Introduction of a New Points Test”, http://www.immi.gov.au/skilled/general-skilled-migration/pdf/points-fact.pdf (accessed on 27/12/2010).

41 Hawthorne (L) and To (A.), English Language Skills Registration Standards – An Australian and Global Comparative Assessment, Melbourne,Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency, 2013 ; Hawthorne (L.), Health Workforce Migration to Australia – Policy Trends and Outcomes 2004-2010, Adelaide, Health Workforce Australia, 2013.

42 Bouma (G.), Mosques and Muslim Settlement in Australia, Melbourne, Bureau of immigration and population Research, 1994, p.xi.

43 Human Rights Commission, Free to Believe? The Right to Freedom of Religion and Belief in Australia, Sydney, Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commissioner, 1997, p.5.

44 Ibid.

45 Soutphommasne (T.), “Australians Unite in Opposing Race Law Change”, The Age, 7 August 2014, p.29.

46 Whelan (A.), 25 Years of EAPS – Review of EAPS Operation in New South Wales, NSW Government, Community Relations Commission, 2009, p.13.

47 Koleth (E.), “Multiculturalism, A Review of Australian Policy Statements and Recent Debates in Australia and Overseas”, Parliamentary Library, Parliament of Australia, Canberra, 2010, p.33. See also http://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/beach-racial-confrontation-australia/ regarding the Cronulla 2005 riots (accessed on 10 October 2015).

48 See Commonwealth of Australia, “A National Action Plan to Build on Social Cohesion, Harmony and Security” (Canberra: Department of immigration and Citizenship), http://www.immi.gov.au/living-in-australia/a-diverse-australia/national-action-plan/nap.htm, accessed 10 February 2011. The website states (1): “The purpose of this National Action Plan (NAP) is to reinforce social cohesion, harmony and support the national security imperative in Australia by addressing extremism, the promotion of violence and intolerance, in response to the increased threat of global religious and political terrorism. It is an initiative of Australian governments to address issues of concern to the Australian community and to support Australian Muslims to participate effectively in the broader community. The NAP is part of the Australian governments’ national strategic framework to address terrorism, developed since the events of 11 September 2001. The framework is based on the principles of maximum preparedness, comprehensive prevention and effective response and recovery. Governments are committed to working in partnership to ensure the NAP is implemented in a co-ordinated and co-operative manner so that duplication does not occur, for example via exchange of information protocols. However, the approach adopted by individual jurisdictions will vary due to local demographic, social, cultural, religious and economic factors and these will be reflected in each jurisdiction’s implementation of the plan.

49 Victorian Multicultural Commission, Enhancing Victoria’s Cultural, Religious and Linguistic Diversity, Annual Report 2008-09, Victorian Multicultural Commission, Melbourne, 2009.

50 Bolt (A.), “Denial Must End Now”, Herald Sun, 17 December 2014, p.11.

51 Whinnett (E.), “$13m Spend on ‘At-Risk’ Young Muslims”, Herald-Sun, 26 August 2014, p.3.

52 Australian Broadcasting Corporation, Budget 2015: Additional $450m to be spent fighting terrorist propaganda, bolstering intelligence agencies, ABC News, Canberra, 2015, http://www.abc.net.au/news/2015-05-12/federal-budget-extra-450-million-to-fight-terrorist-propaganda/6461840 (accessed 13/11/2015).

53 Doorley (N.) and Mullany (A.), “Local Muslims Are Feeling Unfairly Targeted”, Herald-Sun, 13 January 2015, p.6-7.

54 Australia Council, “Arts in a Multicultultural Australia Policy”, 2006, http://2014.australiacouncil.gov.au/about/policies/arts_in_a_multicultural_australia_policy_2006, (accessed on 19/12/2014). Please note while a raft of indigenous arts initiatives exist, they will not be further discussed here.

55 Pratt (J.), “National Cultural Policy Discussion Paper Submission”, Brisbane, Brisbane Multicultural Arts Centre in collaboration with Ethnic Communities Council Queensland, Multicultural Development Association, and select other groups, 2012, p.1.

56 Multicultural Arts Victoria, “Stand Up for Diversity in the Arts”, http://www. multiculturalarts.com.au/membership/shtml (accessed on 6/06/2014).

57 Erickson (H.), “Introduction”, The Media’s Australia, Melbourne, Australian Centre, University of Melbourne, 1996, p.vii.

58 Bertone (S.), Keating (C.) and Mullaly (J.), The Taxidriver, the Cook and the Greengrocer – The Representation of Non-English Speaking Background People in Theatre, Film and Television, Australia Council, 1997, p.ix.

59 Hawthorne (L.), “Representing Difference? Soap Opera in a Multicultural Australia – ‘Heartbreak High’ Versus ‘Home and Away’”, in Bretherton (D.) (ed.), No Longer Black and White – Media Responsibility in Ethnic and Racial Conflict, vol.1, Melbourne, University of Melbourne, 1998.

60 Blake (E.), “Indigenous Actor Gets Stint on Ramsay St”, The Age, 21 July 2014, p.12.

61 Blake (E.), “Call for More Colour-Blind Casting”, The Age, July 16 2014, p.42.

62 Humphrey (M.), “Identity and Media(ted) Violence: Ethnic Conflict, the Media and Globalisation”, in Bretherton (D.), op.cit., p.176.

63 Cater (N.), “Barring Jihadis, We’re Doing Fine”, The Australian, 2 September 2014, p.12.