- Portada

- Volume 19 : 2019

- Exploring Self-determination Referenda in Europe

- Understanding the Occurrence and Outcome of Self-determination Referenda in Europe: a Conceptual and Methodological Introduction

Vista(s): 4374 (17 ULiège)

Descargar(s): 0 (0 ULiège)

Understanding the Occurrence and Outcome of Self-determination Referenda in Europe: a Conceptual and Methodological Introduction

Abstract

In recent decades, there has been an increasing self-determination mobilization within states or sub-state communities in favor of altering the territorial unit that is responsible for (all or parts of) the political sovereignty that is exercised on them. The most particular form of this mobilization are self-determination referenda that allow the population to express their opinion on which territorial unit should be responsible for the exercise of how much political sovereignty on their behalf. This article exposes a conceptual framework that specifies what self-determination entails, who precisely is its holder and what different types of self-determination referenda can exist. In addition, it provides methodological considerations for the selection of cases that are studied in this special-issue and on the generalizability of their findings. In doing so, it paves the way for a comprehensive research on (1) why some communities mobilized for holding a referendum, while others did not, on (2) why some states accepted its organization, while others did not, and ultimately on (3) why it succeed in some places, while it failed in others?

Tabla de contenidos

Introduction

1We currently live in a century of self-determination, where the modern nation-state that has been envisioned from the mid-17th to the mid-20th century as the most suitable unit for both the exercise of political sovereignty and collective popular identification comes under pressure of other territorial units1, above and below. These units take an increasing part in the exercise of sovereignty and appear to be of competing importance for people’s collective identification2. Above, states agreed to delegate political competences to international organizations like the European Union and although some modernist scholars predicted national identities to decline in light of the globalization process3, it seems today that national and supra-national identities are rather cumulative4. Below, sub-national identities appear to have grown even more in importance for people – usually as a complement but sometimes even as opposed to state-wide national identities5, and many states entrust sub-state entities with growing political competences6.

2The most visible expression of these aspirations for self-determination is the mobilization of human communities in favor of altering the territorial unit that is responsible for (all or parts of) the political sovereignty that is exercised on them – and ideally for and by them7. While this mobilization is usually elite-driven in the first place, it requires a wider popular support for being successful8. This support can take the form of public manifestations, of an increasing support for pro-self-determination parties or even degenerate in the use of violence.

3The most particular form of mobilization, however, is the expression of the population via a popular consultation. The reason for this particularity is that it can be considered the most democratic of all means, insofar as it gives every member of the community the same chance of expression – both the mobilized activists and the (usually) silent mass9. At the same time, it is probably also the most contested form of expression10. On the one hand, it consists in an ultimate verdict, which all sides want to win or sometimes simply prevent by all means. On the other hand, even if all sides agree on the organization, complex popular preferences need to be reduced to a limited number of options, whose consequences might be difficult to foresee, and contain a high risk of manipulation in the absence of a comprehensive public debate. Moreover, the people that are entitled to vote might not be the only ones with a stake in the outcome.

4Despite all these difficulties and the stakes being high, various types of self-determination referenda have taken place all over the world. What is more, there has been a considerable variation in both their organization and their outcome. One might indeed wonder (1) why some communities mobilized for holding a referendum, while others did not, (2) why some states accepted its organization, while others did not, and ultimately (3) why it succeed in some places, while in others it did not? The objective of this special-issue is to address these questions through the study of different types of the most recent self-determination referenda in Europe and to understand the political consequences for the cases at hand.

5This introductory article will provide a conceptual framework for this study and develop some methodological considerations for the comparison of cases. In a first section, it will clarify what ‘self-determination’ actually means – ranging from a right to decide on the territorial boundaries of the political unit, to the actual political competences that this unit should exercise. In a second section, it will clarify what kind of groups are under study as potentially aspiring to greater self-determination and what issues arise when determining who the holder of self-determination is. Thirdly, it will clarify what different types of self-determination referenda do exist, what are the approaches of the different actors with a stake in the outcome, and how one should methodologically compare these different types and approaches to generate a broader knowledge both within and across different types of self-determination referenda. Fourthly, the different articles of this special-issue will be presented and situated vis-à-vis the conceptual and methodological considerations of this introduction. Ultimately, some concluding thoughts on the stakes of self-determination referenda in light of this article are provided.

1. The Content of Self-determination: from Autonomy to Independence

6Over time, the concept of ‘self-determination’ has had multiple meanings and uses11. While one could associate it in pre-modern times with the self-rule prerogatives that were granted to seigneuries, monasteries or cities, it was first brought up explicitly together with the modern nation-state paradigm as a moral justification for states’ sovereignty. Since the appearance of sub-state entities that take part in the exercise of sovereignty below the state, it has also progressively been used to justify the self-governance statutes of such entities12.

7In this special-issue, the concept of ‘self-determination’ will be understood as a principle that justifies the exercise of political sovereignty by different territorial units. Thereby, one can distinguish between ‘internal’ and ‘external’ self-determination. Internal self-determination is concerned with the appropriate distribution of political competences across territorial units, be it on the state, sub-state or supra-state level. External self-determination is concerned with the appropriate delineation of the territorial unit that exercises political competences, again on the state, sub-state or supra-state level13.

1.1. Internal Self-determination: the Appropriate Distribution of Sovereignty

8Internal self-determination can be associated with the degree of autonomy that a territory enjoys. According to its Greek etymological roots, ‘autonomy’ qualifies someone or something that gives his·her·it·self its own rules (gr. ‘autos’ means ‘self’; ‘nomos’ means ‘rule’ or ‘law’)14. It can be understood as both an individual and a collective right15. It is an individual right when it refers to the right of individuals to decide upon their lives and to endow themselves with the form of government of their choice. It is a collective right when it refers to the right of communities to govern themselves. As a collective right, with which we are concerned here, autonomy comprises different dimensions of which I distinguish two for the present matter of conceptualization. Both are independent from each other but the legal prerogatives that come with them can be conceived as cumulative – ultimately resulting in a territorial unit’s degree of autonomy.

9A first dimension, which is usually called ‘self-rule’, concerns the extent to which a territorial unit is actually entitled to determine the content of part of the rules according to which it lives. The depth of this self-rule is determined by both the capacities of the institutions it obtained and the policy scope that falls under its competences. As for the capacities of institutions, one can distinguish between advisory, administrative and legislative capacities. Advisory capacities allow a territorial community to officially represent the group’s interests vis-à-vis state institutions or officials. Administrative capacities allow a territorial community to implement specific policies for their group that have been previously adopted by state institutions. Legislative capacities, finally, allow a territorial community to adopt the rules that determine the content of specific policies for their group. While advisory and administrative capacities are, on their own, again not sufficient for qualifying as an autonomy statute, they may add up to already present empowerment rights and come closer to a critical threshold from which one can speak of an autonomy statute. The latter begins, in fact, once a territorial community obtains legislative self-rule prerogatives and then extends as a function of the policy domains for which legal rules may be adopted.

10A second dimension, which is usually called ‘shared rule’, concerns the extent to which a territorial community is entitled to co-decide with other territorial groups or entities on rules that are applicable to all of them. One aspect of shared-rule is the representation of territorial communities within institutions where common rules are adopted (i.e. in a statewide parliament) or executed (i.e. in a statewide government). Another aspect of shared-rule is the extent to which a territorial community can co-determine the content of common rules and whether its final approval is required. While shared rule can be conferred independently from self-rule and is hence, on its own, theoretically not sufficient for qualifying as an autonomy statute, it is often conferred in parallel to legal self-rule capacities and can be conceived as adding-up to other autonomy prerogatives.

11The use of a referendum could be imagined for determining to which extent the populations supports the adaptation of an existing distribution of sovereignty – consisting in the cumulative prerogatives of one or more of the aforementioned dimensions. This adaptation could go into two directions: towards greater devolution, i.e. an increase of autonomy prerogatives, or towards greater revolution, i.e. a decrease of autonomy prerogatives. Within the state, autonomy referenda can be considered those who deal with the distribution of powers between the state and sub-state level entities. Across states, autonomy referenda can be considered those who deal with the distribution of powers between the state and a supra-national organization.

1.2. External Self-determination: the Appropriate Unit for the Exercise of Sovereignty

12External self-determination relates to the delineation of the territorial unit that exercises political competences. This is conceptually most clear and practically probably most easy when the boundaries of sub-state territorial units are concerned. The delineation of the boundaries of a state is more complex. De facto, independent statehood can be regarded as the most extreme form of external self-determination, i.e. the exercise of political sovereignty in all policy domains. De jure, however, several additional elements are required: a permanent population, a defined territory, a government and the capacity to enter into relations with other states16. Given that today, there are no more ‘terra nullius’, i.e. a territory possessed by no one, becoming a newly independent state can only be achieved by three means: through secession from an existing state, through the splitting of an existing state or through the fusion of two existing states (or parts thereof, which would again imply some form of secession)17.

13The use of a referendum for the determination of new (sub-)statehood is particular insofar as the birth of the (sub-)state would rely on more than just the use of power and would have a broader popular consent18. What remains controversial, however, is to determine whose consent is needed. Only that of the population of the territorial unit seeking regional or national independence? Or, in the case of a splitting or secession, also that of the remaining population of the region or state to which the territorial unit belong(s)ed19 ?

2. The Holder of Self-determination: between Territories and Populations

14Different types of groups may aspire to greater self-determination and should hence be included in this study. When the statute of an existing state is concerned, usually in its relation to a supra-national organization, the unit of analysis is that very state. When the statute of a sub-state entity is concerned, the unit of analysis is that sub-state entity. While this distinction is fairly intuitive, significant ambiguity can arise on what a state or a sub-state entity actually encompasses and who the ultimate holder of self-determination is.

15The exercise of political sovereignty in the traditional Weberian sense is constituted by (1) the monopoly of government, (2) of (and by) a human community, (3) in a specified geographical area20. This holds true regardless of the state-level since in a setting of multi-level governance, different kinds of political competences can be exercised for different groups of people in different geographical areas. In this ‘nexus’ of sovereignty, population and territory21, there are two ways of conceiving the conferral of self-determination – ranging from a right that is conferred to a specific population, to a statute that is conferred to a specific territory.

16Considering self-determination as being conferred to a specific population can take three forms22. First, as the self-government right of a specific (sub-)national group. Secondly, as the self-government right of a specific (sub-)national group but accounting for the presence of non-group members among the population. Thirdly, as the self-government of a group with an open, civic (and almost territorial) form of (sub-)national identity. What is at stake between these approaches is the extent to which the (sub-)national population overlaps with the territory where the legal scope of the self-determination statute is exercised. The less this is the case, the more a purely personal approach of self-determination creates minorities within (sub-)state units23.

17Considering autonomy as being conferred on a solely territorial basis is often associated with a purely administrative logic of competence devolution. This might be correct in cases where competences are devolved to sub-state level entities without particular group identity. Yet, one should not forget that some human dimension is always present and that institutions can, even after some time, animate latent territorial identities24.

18The contributions in this special-issue aim at taking into account both the territorial and identitarian dynamics behind self-determination aspirations. Thereby, the overlap between territories and identities may vary from case to case. Moreover, group identifications are not assumed to be unanimous across all members of a community, leaving room for multiple and cumulative identities25, whose combination and importance can vary over time26. While the level of analysis is, a priori, the group level, one should keep in mind the important warning against ‘groupism’ by Brubaker and remember that groups are constituted in a heterogeneous manner by members who can not only have different sentiments of identification and attachment but even varying interests which contribute to a complex group agency27.

3. Understanding the Occurrence and Outcome of Self-determination Referenda

19Understanding the occurrence, outcome and political consequences of self-determination referenda requires particular attention in three regards. First, when selecting and comparing cases, one should not confound different types of self-determination referenda. Secondly, when collecting data on these cases, the (potentially competing) perspectives of multiple actors need to be taken into account. Thirdly, when comparing the findings of different cases, one should distinguish between what is generalizable for self-determination referenda in general (cross-type inference) and what is generalizable for particular types of them (within-type inference). Moreover, one should think about the benefit of including negative cases in the analysis. This section discusses each of these points in further detail.

3.1. Different Types of Self-determination Referenda and Actors of Interest

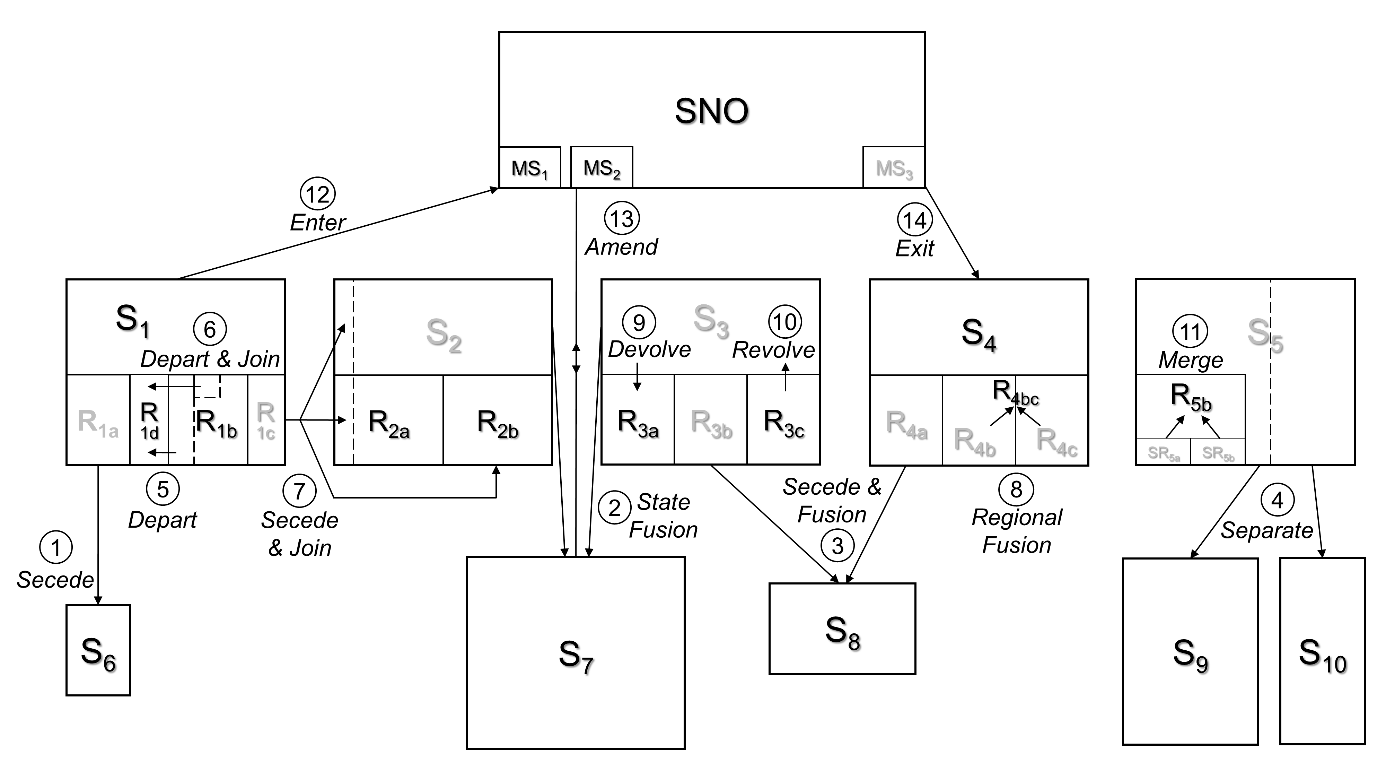

20As illustrated in Figure 1 hereunder, one can distinguish between fourteen types of self-determination referenda. While all of them are theoretically possible, not all of them have (yet) occurred in praxis. The typology aims to cover all types of self-determination referenda that are possible on a state and sub-state level, but local varieties may be possible below these units.

21Referenda leading to the creation of a new state:

1. Secede: referendum on the secession of a regional entity from its state (e.g. the Scottish referendum in 2014).

2. State fusion: referendum on the fusion of two states (none happened so far).

3. Secede & Fusion: referendum on the fusion of two regional entities that would secede from their state and create a new one (none happened so far).

4. Separate: referendum on the separation of an existing state in two new states (e.g. the referendum on the separation of Norway and Sweden in 1905).

22Referenda altering the territorial unit of regional entities:

5. Depart: referendum on the departure of a part of a regional entity which would form a new sub-state entity within the state (e.g. the Jura referendum in 1974).

6. Depart & Join: referendum on the departure of a part of a regional entity which would join another regional entity within the state (e.g. the Jura referenda in 1975, 2013 and 2017).

7. Secede & Join: referendum on the secession of a regional entity which joins another state as new regional entity, as part of an existing regional entity or without regional statute (e.g. the Schleswig referendum in 1920).

8. Regional fusion: referendum on the fusion of two or more regional entities that remain within the state (e.g. the referendum on the creation of Baden-Württemberg in 1951).

23Referenda altering the political competences of regional entities:

9. Devolve: referendum on the transfer of political competences to a regional entity (e.g. the Welsh referendum in 2011).

10. Revolve: referendum on the transfer of political competences from a regional entity back to the state (none happened so far).

11. Merge: referendum on the transfer of political competences of sub-regional entities to regional entities, de facto merging both institutions (e.g. the 2003 referendum on becoming a ‘single territorial collectivity’ in Corsica).

24Referenda altering the statute of states within supra-national organizations:

12. Enter: referendum on the entrance of a state to a supra-national organization (e.g. the Austrian referendum on its entrance to the European Community in 1994).

13. Amend: referendum on the amendment of the functioning of a supra-national organization in one of its member states (e.g. the French referendum on the EC Maastricht Treaty in 1992).

14. Exit: referendum on the departure of a state from a supra-national organization (e.g. the referendum on the departure of the United Kingdom from the EU in 2016).

Figure 1: Schematic representation of the fourteen types of self-determination referenda

SNO = supra-national organization. S = state. R = regional entity. SR = sub-regional entity. Gray: entity that would cease to exist if the referendum succeeds (S3 ceases to exist because of referendum (2), not because of (9) or (10)).

25In addition to different types of self-determination referenda, there are different types of actors that have an interest in the outcome28. While not all might be present in all types, particular attention needs to be paid to their potentially competing interests and the impact they have on the occurrence, outcome and consequences of the popular consultation.

1. A state: with both elite actors and a (majority) population.

2. A sub-state entity: with both elite actors and a (minority) population.

3. A minority population within the sub-state entity identifying with the state.

4. A minority population within the sub-state entity identifying neither with the state nor with the sub-state entity.

5. External actors:

a. Kin-states, i.e. a foreign state with linguistic or historical commonalities with the sub-state entity in another state.

b. States with geopolitical interests.

c. Supra-national organizations to which the state in which the referendum takes place belongs.

d. The world community.

3.2. Cross-case Selection, Comparison and Generalizability

26The conceptual differentiation between the different types of self-determination referenda and the actors of interest is important for both the selection of cases under study and the comparison of the findings for each of them.

27For the case selection, what is at stake is to select both similar and different cases. Cases should be similar, insofar as one would want to have a conceptually coherent unit of analysis, i.e. states or territorial communities where one would expect a self-determination referendum to take place. Cases should be different, in turn, insofar as one might want to have variation in types, occurrences and outcomes. First because it allows to identify similarities and differences across types. Secondly, because understanding the occurrence and outcome of a particular referendum might benefit from the lessons of a deviant case constituting a logical counterfactual. One can have deviance in consistency, i.e. when one would have expected a referendum and/or a particular result to occur but it did not, and deviance in coverage, i.e. when a referendum and/or particular result occurs, although one would not have expected it. In both cases, better knowledge on the factors that explain the occurrence and outcome are obtained29.

28For the generalizability, what is at stake is to determine which findings can be generalized for self-determination referenda in general (cross-type inference) and which findings are only generalizable for particular types of them (within-type inference)30. Cross-type inferences can be drawn from explanatory factors at a high level of abstraction. As contextual factor, for example, one could imagine that a social or political crisis plays a similar role in all self-determination referenda. Equally, the behavior of actors that want to change the current statute and that of those who want to keep the status quo might lead to similar competing dynamics. Many other issues can furthermore be expected to be similar, like the presence of minorities within minorities, or the need to reduce complex popular preferences to a limited number of options whose consequences might be difficult to foresee. Within-type inferences, in turn, are drawn from explanatory factors at a medium level of abstraction. A territory’s capacity of autarky, for example, is only relevant for independence referenda, just as issues around the ideal division of political competences only play a role in autonomy referenda. At a low level of abstraction, finally, inferences are usually limited to the case at hand.

4. About this Special-Issue

29This special-issue comprises seven contributions on several of the most recent self-determination referenda in European states. Thereby, the articles cover six different types of consultations (secession (type 1), departure (type 5), departure and joining (type 6), devolution (type 9), merging of regional and sub-regional institutions (type 11) and the exit from a supra-national organization (type 14)). While most of them are typical case studies, one deviant case study is included. Moreover studies cover both accepted and rejected referenda.

30Juan Rodríguez Teruel and Astrid Barrio López start with an article on the Catalan independence referendum that was held in 2017. They provide interesting insights on a consultation on which state and sub-state actors fundamentally disagreed.

31Jérémy Dodeigne and myself hand in by looking into the deviant Flemish case where, despite the presence of a strong regionalism and pro-independence parties holding 49% of Flemish seats in the national parliament, no secession referendum occurred.

32We then turn to an article on the case of Greenland where Maria Ackrén explains the occurrence and outcome of the 1979 and 2008 devolution referenda, and what the prospects for a future secession referendum are.

33André Fazi undertakes the impressive tasks of comparing four different devolution referenda in France that were concerned with the merging of regional and sub-regional institutions. That of Corsica and Guadeloupe in 2003, those of Martinique in 2003 and 2010, that of Guyana in 2010, and that of Alsace in 2013, which were all rejected for different reasons.

34In their article on the referenda that were held in the Swiss cantons of Jura and Berne in 1974, 1975, 2013 and 2017, Liliane Minder and Simon Mazidi deal with two very particular types of self-determination referenda, namely on whether a part of a sub-state entity should depart and constitute an own sub-state entity, and whether a part of a sub-state entity should join another one. Thereby, they explain how it came that some of the referenda in the Swiss Jura were accepted while others were not.

35The only referendum that was organized until today on the departure of a state from a supra-national organization, the so-called Brexit, is covered by Sergiu Gherghina and Daniel O’Malley who explain how to understand the occurrence and outcome of the probably most publicized self-determination referendum of the last decades.

Conclusion

36In recent decades, there has been an increasing self-determination mobilization within states or sub-state communities in favor of altering the territorial unit that is responsible for (all or parts of) the political sovereignty that is exercised on them. The most particular form of this mobilization are self-determination referenda that allow the population to express their opinion on which territorial unit should be responsible for the exercise of how much political sovereignty on their behalf. This article exposed a conceptual framework that specified what self-determination entails, who precisely is its holder and what different types of self-determination referenda can exist. It provided methodological considerations for the selection of cases that are studied in this special-issue and on the generalizability of their findings. In doing so, it paved the way for a comprehensive research on (1) why some communities mobilized for holding a referendum, while others did not, on (2) why some states accepted its organization, while others did not, and ultimately on (3) why it succeeded in some places, while in others it did not?

37The stakes for these questions to be resolved are high. Not only can the mere occurrence of a self-determination referendum have an important impact on the political stability of the state in which it is held – both when it takes place and when it is prevented. More importantly, when political competences are devolved, revolved or merged, it is difficult to foresee whether this will accommodate existing demands or even incite further of them31. When the restructuration of territorial boundaries is concerned, especially in independence scenarios, multiple at least as controversial issues arise – from the presence of minorities within minorities, to questions of consent of both minority and majority populations to the new statute.

38It has been pointed out initially that we currently live in a century of self-determination. One particular manifestation of this era are popular consultations that allow people to determine which territorial unit should be responsible for the exercise of how much political sovereignty on their behalf. At the same time, one should not forget that holding such consultations is usually the exception when it comes to decisions on the constitutional statute of states and sub-state units. While this exceptionalism might, on its own, raise normative questions that go beyond the scope of this research, it also incites for putting self-determination referenda into a broader perspective. This perspective needs to take into account that self-determination referenda are one possible mode of expression of popular opinions in a self-determination era where people’s collective identifications and preferences about the exercise of political sovereignty are both multiple and evolving.

Notes

1 Van Creveld (M.), The Rise and Decline of the State, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1999.

2 Keating (M.), Plurinational Democracy. Stateless Nations in a Post-Sovereignty Era, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2001.

3 Hobsbawm (E. J.), Nations and Nationalism since 1780: Program, Myth, Reality, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1992, p. 191.

4 Duchesne (S.) et Frognier (A.-P.), ‘National and European Identifications: A Dual Relationship’, Comparative European Politics, vol. 6, n° 2, 2008, pp. 143-168, p. 162.

5 Miller (D.), Citizenship and National Identity, Cambridge, Polity Press, 2000, pp. 127-131.

6 Hooghe (L.), Marks (G.), Schakel (A.), Chapman-Osterkatz (S.), Niedzwiecki (S.) et Shair-Rosenfield (S.), Measuring Regional Authority. A Postfunctionalist Theory of Governance, Volume I, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2016, pp. 155-156.

7 I drew here on the famous address that Abraham Lincoln held on November 19th, 1863 in Gettysburg and where he described a free state as the “government of the people, by the people, for the people”.

8 Keating (M.) et McGarry (J.) Minority Nationalism and the Changing International Order, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2001, pp. 5-6.

9 Şen (İ. G.), Sovereignty Referendums in International and Constitutional Law, Cham, Springer, 2015, pp. 26-32.

10 Ibid., pp. 34-38.

11 Van Creveld (M.), op.cit.

12 For a more detailed account on the multiple meanings of the concept of self-determination (and their legal foundations), cf. Hipold (P.), ‘Self-determination and autonomy: between secession and internal self-determination’, in Hipold (P.), Autonomy and Self-determination. Between Legal Assertions and Utopian Aspirations, Cheltenham & Northampton, Edward Elgar, 2018, pp. 7-55.

13 I borrowed the ‘internal’-‘external’ terminology from Hipold (P.), op. cit., pp. 10-16, while slightly adapting its meaning for the purpose of this conceptualization.

14 It is of no surprise that the English term first comes up in the 17th century following the works of Enlightenment philosophers like Locke, Rousseau and Kant. Cf. Oxford English Dictionary, Autonomy, http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/13500?redirectedFrom=autonomy#eid (consulted on September 2nd, 2018).

15 Loughlin (J.) ‘Regional Autonomy and State Paradigm Shifts in Western Europe’, Regional & Federal Studies, vol. 10, n° 2, 2000, pp. 10-34, here p. 10.

16 Cf. art. 1 of the Montevideo Convention on the Rights and Duties of States, adopted on December 26th, 1933.

17 Behrendt (C.) et Bouhon (F.), Introduction à la Théorie générale de l'Etat. Manuel, Bruxelles, Larcier, vol. 3, 2014, pp. 69-99.

18 For a theory on the use of power as foundation of the birth of a state, cf. Bodin (J.), Les six livres de la République, Paris, Fayard, 1986 (1576). For a theory on popular consent as the foundation of the birth of a state, cf. Rousseau (J.-J.), Du contrat social, Paris, Flammarion, 2014 (1762).

19 In its famous Judgment 25506 (1998), the Supreme Court of Canada ruled for example that “the negotiation process precipitated by a decision of a clear majority of the population of Quebec on a clear question to pursue secession would require the reconciliation of various rights and obligations by the representatives of two legitimate majorities, namely, the clear majority of the population of Quebec, and the clear majority of Canada as a whole” (art. 93).

20 Weber (M.), Politik als Beruf, Leipzig, Reclam, 1992 [1919], p. 6.

21 The conceptualization of this nexus draws on Malloy (T. H.), ‘Introduction’, in Malloy (T. H.) et Palermo (F.), Minority Accommodation through Territorial and Non-Territorial Autonomy, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2015, pp. 1-9, here p. 2-6.

22 Palermo (F.), ‘Owned or Shared Territorial Autonomy in the Minority Discourse’, in Malloy (T. H.) et Palermo (F.), Minority Accommodation through Territorial and Non-Territorial Autonomy, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2015, pp. 13-32, here pp. 15-19.

23 Ibid., here p. 29.

24 Nagel (J.), ‘Constructing Ethnicity: Creating and Recreating Ethnic Identity and Culture’, Social problems, vol. 41, n° 1, 1994, pp. 152-176.

25 Keating (M.), Nations against the State: The New Politics of Nationalism in Quebec, Catalonia and Scotland, London & New York, Palgrave Macmillan, 1996, p. 217.

26 Moreno (L.), ‘Scotland, Catalonia, Europeanization and the ‘Moreno Question’’, Scottish Affairs, vol. 54, n° 1, 2006, pp. 1-21.

27 Brubaker (R.), Ethnicity without Groups. Cambridge (Massachusetts): Harvard University Press, 2004.

28 I largely borrowed the typology hereunder from Müllerson (R.), ‘Self-determination and secession: similarities and differences’, in Hipold (P.), Autonomy and Self-determination. Between Legal Assertions and Utopian Aspirations, Cheltenham & Northampton, Edward Elgar, 2018, pp. 77-96, here pp. 78-79. I only inversed two points (3. and 4.) and added supra-national organizations (c.) to it.

29 For further details on the combination of typical and deviant cases in a comparative case study research, cf. Schneider (C. Q.) et Rohlfing (I.), ‘Combining QCA and process tracing in set-theoretic multi-method research’, Sociological Methods & Research, vol. 42, n° 4, 2013, pp. 559-597. ; Beach (D.) et Pedersen (R. B.), ‘Selecting Appropriate Cases when Tracing Causal Mechanisms’, Sociological Methods & Research, 2016, pp. 1-35.

30 For further details on generalization in comparative case study research, cf. Gerring (J.), Case Study Research: Principles and Practices, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2016.

31 For further details on this so-called ‘paradox of federalism’, cf. Erk (J.) et Anderson (L.), ‘The Paradox of Federalism: Does Self-Rule Accommodate or Exacerbate Ethnic Divisions?’, Regional & Federal Studies, vol. 19, n° 2, 2009, pp. 191-202.