- Accueil

- Volume 19 : 2019

- Exploring Self-determination Referenda in Europe

- The Flemish Negative Case: Explaining the Prevalence of Regionalist Demands without Request for an Independence Referendum

Visualisation(s): 5183 (9 ULiège)

Téléchargement(s): 0 (0 ULiège)

The Flemish Negative Case: Explaining the Prevalence of Regionalist Demands without Request for an Independence Referendum

Abstract

Despite Flanders is often presented as a handbook example of strong regionalism, the organization of a referendum on Flemish independence has never been on the political agenda. This article explains the reasons for the absence of a self-determination referendum in Flanders and shows that, since the 2000s, the omnipresence of the self-rule issue at the top of the political agenda is not – per se – a direct response to regionalist demands of Flemish voters or the Flemish political class. Instead, it is the consociational features of the Belgian political system that enhance intra-community party competition and contribute to the escalade of inter-community conflicts. This mostly explains the deep constitutional crises of the late 2000s and early 2010s. In this context, we can better understand why Flanders independence is supported neither by a majority of the population (9.5 percent), nor its representatives (except those belonging to one of the two regionalist parties, N-VA and VB).

Table des matières

Introduction

1Flanders in Belgium is often presented as one of the “usual suspects” in regional and federal studies. Along with other regions such as Catalonia, Scotland, or Quebec, Flanders is a typical case for a strong regionalism according to the two main criteria in Swenden’s definition of regionalism, namely the strength of ethnoregionalist parties as well as of a regional identity1. In Flanders, ethnoregionalist parties (the N-VA and Vlaams Belang) are strong political actors – if not the strongest – even though their electoral success has evolved over time and across regional and national elections2. Moreover, citizens’ self-identification with Flanders instead of the central Belgian state is (among) the highest in comparison to the other two regions of the country (Brussels and Wallonia)3.

2In comparison to other ‘hot’ cases of strong regionalism where independence referenda were organized (e.g. in Quebec, Catalonia, and Scotland), the organization of a referendum on Flemish independence is, however, rather unlikely – if not impossible. In addition to the practical difficulties of a Flemish independence scenario (e.g. what happens with Brussels Capital-Region claimed by both Wallonia and Flanders4), all past and recent surveys unmistakably show that the independence path is not desired by the Flemish electorate, nor by the majority of the Flemish political class. In this contribution, we will demonstrate that the institutional architecture of the Belgian federalism has created intra- and inter-community tensions since the 2000s. In particular, we will show that the conditions explaining (the paradox of) an over-representation of autonomist demands by Flemish political parties must be explained by the specific features of the Belgian institutional context. This institutional context explains why autonomy issues are at the top of the political agenda, while self-rule preferences are hardly supported in Flanders and pro-independence preferences even less.

3The paper is structured as follows. First, we present a brief overview on the process of federalization in Belgium. Secondly, we present voters and MPs’ preferences vis-à-vis self-rule autonomy in Flanders in comparison to Wallonia (from 1991 to 2014). Thirdly, we demonstrate that the consociational features of the Belgian political system enhance intra-community party competition while contributing to the escalade of inter-community conflicts. This mostly explains the deep constitutional crises of the late 2000s and early 2010s.

1. A very brief history of Belgian federalism

4Belgium is one of the handbook examples of a peaceful transition towards a federation for students of regional and federal studies. Over a few decades, the country experienced deep transformations of its institutions – a former unitary and centralized country inherited from the early 19th century’s state conception – that evolved into a fully-fledged federation. The processes of regionalization have been taking place from 1970 onwards and constitutionally entrenched both its linguistic and territorial diversity. The so called ‘reforms of the state’ were implemented but not without political costs: the country experienced about two decades of political instability causing the fall of numerous national governments whose duration accounts amongst the shortest in Belgium’s modern political history. Institutional reforms started, though, to produce stabilizing effects on the political system. Since 1993, the first article of the Constitution states that “Belgium is a federal state, composed of communities and regions”. While communities were created by the first state reform in 1970 and received person-related powers, regions were established by the second state reform in 1980 and received competences related to territorial management. The third state reform, in 1989, granted a regional statute to the Brussels-Capital region. While still unachieved, the Belgian federal structure presented its basic feature, namely two partially overlapping sub-state level entities. The Dutch-, French- and German-speaking Communities, and the Flemish-, Walloon- and Brussels-Capital Regions.

5The fourth state reform in 1993 enlarged the sub-state entities’ competence and institutional autonomy (amongst others, the direct election of regional parliaments). It was meant to be the last wave of institutional reconfiguration when Prime Minister Dehaene declared that “the roof was put on the federal house.” The newly created federation opened indeed a novel political era: the previous two decades of political instability (1970-1992) pathed the way to 15 years of political stability (1992-2007). During that period, all federal governments survived during their legislative terms. Community conflicts between Flemish and Francophone political parties seemed to have been eradicated from the political agenda and, when they surfaced, they were settled without government crisis (e.g. the fifth minor reform of the state in 2001)5.

6Belgian federalism’s golden era was, however, only of short duration. In the mid-2000s, Flemish parties put forward new demands for greater self-rule autonomy, which were firmly opposed by French-speaking parties. At that time, the country had resumed its ‘old practices’ of political crises and government instability. There was firstly the 2007-2008 political crisis in which a government finally emerged but did not manage to solve Flemish parties’ claims for further institutional reforms. In 2010, anticipatory federal elections were triggered and, as Belgium mined deeper into the community crisis, it even broke the world record of a country without a national government (541 days). It was only in 2014 that a sixth state reform, which consisted in a major autonomy devolution to the sub-state level entities, could somewhat settle the disputes.

7This evolution of Belgium politics is puzzling, especially in comparison to other regions analysed in this special issue. While Scottish or Catalan citizens have been discussing independence in the recent years, the latter is completely out of the political agenda in Flanders. In the latter, demands for greater regional autonomy are only remotely supported by Flemish voters since the 1990s. Besides, even though greater support for self-rule has recently increased in Flanders, they are not that dissimilar from Francophone voters. This is introduced in the next section.

2. Voters’ preferences about regional autonomy in Flanders and Wallonia-Brussels

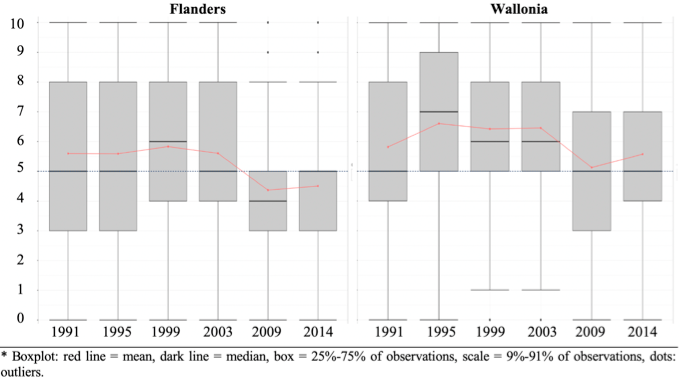

8In this section, we present Belgian voters’ preferences about regional autonomy based on two types of datasets. On the one hand, we use the ISPO-PIOP voter surveys collected from 1991 to 2007. These surveys were developed simultaneously with representative samples of Flemish and Francophone voters and used identical questionnaires. All surveys were conducted during the year of a federal election. Given the 2010 anticipatory federal elections we cannot, however, present reliable data for that electoral year. On the other hand, we use datasets from the PartiRep inter-university project for the 2009 (regional) and 2014 elections (regional, federal and European). Both the ISPO-PIOP and PartiRep surveys used the same wordings of questions about voters’ preferences for self-rule autonomy. This allows us to compare trends across regions and over time during more than two decades6. The first question to describe ‘what citizens think and want’ about the institutional structure of the Belgian state is the devolution scale. Voters were asked to position themselves on a 10-points Likert scale. While ‘0’ entailed that ‘the sub-state level entities would have all the powers’, ‘10’ described the scenario where ‘the federal Government would have all powers’. The value ‘5’ explicitly indicated a preference for the status quo, i.e. ‘being satisfied with the current situation’.

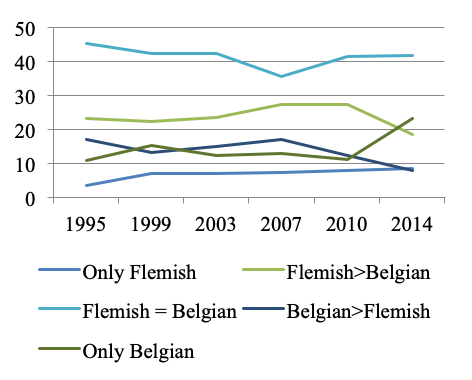

9Figure 1 presents descriptive statistics with boxplots for Flemish and Francophone voters together with the evolution of the average within each region. During the 1990s and up to the early 2000s, we observe a neat stability both in Flanders and in the French-speaking part of the country. Although Francophone voters are slightly more in favour of transferring powers back from the sub-state institutions towards the federal government, Flemish voters have alike preferences. In fact, if there is any trend noticeable during that period, it is one towards a stronger federal government, not towards stronger sub-state entities (as denoted by the greater portion of the Flemish boxplots above the 5-status quo line in 1999 and 2003).

10After the 2003 federal elections, there is however a notorious shift since average preferences within each region drop substantially (outside statistical margins of error). This indicates a larger support for further state reforms empowering regional institutions. This evolution is most distinctive and radical in Flanders as the average score (4.4) indicates support for greater regional autonomy. Moreover, the Flemish electorate seem to be more convergent on that question in 2009 and 2019: the grey box representing 50 percent of all Flemish voters is smaller (indicating less differences among voters) while being entirely located into the status and regionalization area (values equal and below 5). As a matter of fact, only the upper whisker (upper 25%) presents voters with “refederalising” preferences. As we will show later, this increase was facilitated by the rise of the Flemish nationalists N-VA and the publicity of their strong regionalist campaign during the political crisis of 2009-2011. In Wallonia, the average score remains just above the status quo scenario, but the shape of the 2009 boxplot distinctively shows a net increase of pro-regionalization voters in the South of the country, probably as a response to tendencies in Flanders and the political difficulties on the federal level that come with it. At about the same period, we can directly assess Flemish voters’ preferences for an independent Flemish (a question that has been rarely included in voter survey). The 2007 Flemish voter survey show that support for this scenario is clearly weak with 9.5 percent7.

11After the 2014 elections, few changes are observed in comparison to 2009. While it can be concluded that the promises of the new Belgian federalism came to fruition (easing territorial tensions in its early area), demands for greater regionalization remain among Flemish voters – although to a lesser extent since both the mean and median positions get close to the status quo.

Figure 1. Voters preferences about regional autonomy in Flanders and Wallonia-Brussels

12In Wallonia, one can even observe a slight increase in support of a refederalisation of competences. Demands for greater regional autonomy in the Belgian context could be explained by the ‘paradox of federalism’. Indeed, regionalization was seen “as a way to accommodate territorially based ethnic, cultural and linguistic differences in divided societies, while maintaining the territorial integrity of existing states”8. At the same time, “recognition also means that collective groups will have the institutional tools to strengthen their internal cohesion, heightening the ‘us vs. them’ mindset. The paradox of collective representation is that it perpetuates the very divisions it aims to manage. Furthermore, it provides the tools that reduce the costs of secession, thereby making it a realistic option”9. The development of regional institutions could therefore have strengthened subnational entities - the ‘us vs. them’ mindset - leading to demands of self-rule autonomy.

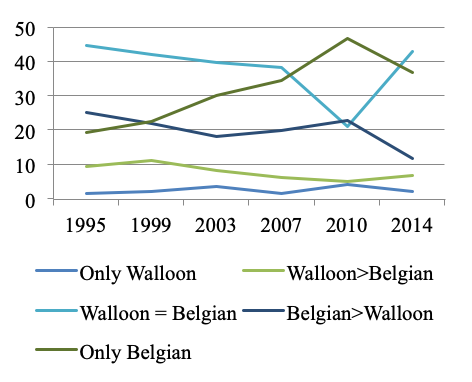

13However, the effects of the paradox of federalism did not emerge instantly once sub-state institutions are created. It evolved incrementally as these institutions demonstrate their ability to deliver in terms of policy-making. About 15 years after the first direct elections of the regional parliaments in 1995, the side effects of regionalization are a plausible hypothesis for the Belgian case. We therefore analyse voters’ self-identification based on the ‘Linz-Moreno question’10. To the question “of which unity do you consider yourself part in the first and the second place?”, respondents had the choice between five items: (1) Belgian only, (2) more Belgian than regional, (3) equally Belgian and regional, (4) more regional than Belgian, (5) only regional11.

Figure 2. Evolution of identities in Flanders and Wallonia (1995-2014) in percentages

|

|

14* Source: ISPO-PIOP 1991-2010; PartiRep 2009-2014. Results weighted by socio-demographic variables.

15Figure 2 presents the evolution of identifications according to the Linz-Moreno question from 1995 to 2014. They show that regional identities are stronger in Flanders than in Wallonia. Nevertheless, the results do not confirm the expectations of the paradox of federalism with a rise of regional identity in Flanders. Hence, the ‘only Flemish’ category is the least chosen item for the entire period until 2010. On the opposite, the category with nested identities (‘equally Belgian and Flemish’) is the most frequent covering more than 40 percent of Flemish voters. In fact, the most notorious change observed in Flanders is the category of voters who feel ‘only Belgian’ (23 percent) that is about twice as much as in 2010. In the meantime, the proportion of voters feeling ‘more Flemish than Belgian’ decreased from 27 percent to 18 percent. In other words, we observe very stable identities and, when they evolve, we observe Flemish voters feeling ‘more Belgian’, not ‘more Flemish’.

3. Parties’ preferences about regional autonomy in Flanders and Wallonia-Brussels

16While data has been available for voters since the 1970s, this empirical material is less frequent for political elites. More recently, MP surveys have been conducted in Belgium to study the political class’ preferences vis-à-vis self-rule autonomy12. The first survey was conducted in 2011 – just before the 6th reform of the state – among members of the Chamber of Representatives, the Senate, the Walloon Parliament, the Parliament of the Brussels-Capital Region, the Flemish Parliament and Parliament of the German-speaking Community. The second survey took place immediately after the formation of the sub-state (June-July 2014) and as federal government (October 2014). Compared to international survey standards in other countries, the 2015 participation rate of 61.8 percent is particularly high. This is also a significant development compared to the 2011 survey (+ 12.0 percent).

17The objective was to survey federal and sub-state MPs outside any period of major political crisis (such as executive formation or political gridlock) but right after the federal and regional elections of May 25, 2014 (the first elections after the adoption of the 6th reform of the state). The comparison of the 2011 and 2014-2015 MP surveys is, therefore, particularly enlightening to understand the evolution of the political class self-rule preferences before and after the 6th reform of the state. The surveys asked MPs asked to position themselves on the exact same 10-points Likert scale used in the voter surveys. Table 1 presents the results of the 2014-2015 survey, comparing them with those collected in 2011. Three elements are presented for each party: the average score, the congruence of its MPs (standard deviation) and the dominant scenario emerging from the party.

Table 1. MPs’ preference for self-rule autonomy (comparison of 2011 and 2015)13

|

2011 MP survey |

2014-2015 MP survey |

Difference mean score |

||||||

|

Mean |

Std. Dev. |

Main party preference |

Mean |

Std. Dev. |

Mani party preference |

|||

|

French-speaking parties |

PS |

4.8 |

1.9 |

Regionalisation |

5.2 |

1.4 |

Refederalisation |

+ 0.4 |

|

MR |

3.9 |

1.4 |

Regionalisation |

5.7 |

1.9 |

Refederalisation |

+ 1.8 |

|

|

CDH |

4.3 |

1.4 |

Regionalisation |

5.5 |

1.3 |

Refederalisation |

+ 1.2 |

|

|

Écolo |

4.2 |

1.4 |

Regionalisation |

5.3 |

1.4 |

Refederalisation |

+ 1.1 |

|

|

FDF |

4.6 |

1.8 |

Regionalisation |

5.0 |

2.3 |

Status quo |

+ 0.4 |

|

|

PTB |

- |

- |

Regionalisation |

8.5 |

1.0 |

Refederalisation |

- |

|

|

All MPs |

4.3 |

1.6 |

Regionalisation |

5.5 |

1.7 |

Refederalisation |

+1.2 |

|

|

Flemsih parties |

N-VA |

0.4 |

0.8 |

Regionalisation |

0.6 |

0.9 |

Regionalisation |

+ 0.2 |

|

CD&V |

3.0 |

1.0 |

Regionalisation |

4.5 |

1.2 |

Regionalisation |

+ 1.5 |

|

|

Open VLD |

3.9 |

2.3 |

Regionalisation |

5.2 |

1.7 |

Refederalisation |

+ 1.3 |

|

|

SP.A |

4.4 |

1.5 |

Regionalisation |

5.8 |

1.6 |

Refederalisation |

+ 1.4 |

|

|

Groen |

4.9 |

1.5 |

Regionalisation |

5.8 |

1.7 |

Refederalisation |

+ 0.9 |

|

|

VB |

0.0 |

0.0 |

Regionalisation |

0.4 |

1.1 |

Regionalisation |

+ 0.4 |

|

|

LDD |

4.0 |

4.2 |

Regionalisation |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

Independents* |

0.0 |

0.0 |

Regionalisation |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

All MPs |

2.7 |

2.3 |

Regionalisation |

3.9 |

2.5 |

Regionalisation |

+1.2 |

|

18In 2014-2015, there are two main outliers: the ethnoregionalist parties N-VA and VB with an average score of 0.6 and 0.4 respectively. Their MPs support independence for Flanders as 0 means that all powers would be transferred from the Federal authority to the sub-state levels (Regions and Communities). Nothing surprising as the MPs of these two parties express the fundamental objective entrenched in the statutes of their parties. On the other hand, the mean scores of all the other parties are very similar. With one exception, they range from 5.0 (i.e. the status quo in terms of federalization) and 5.8: 5.0 for FDF, 5.2 for PS and Open VLD, 5.3 for Ecolo, 5.5 for the CDH, 5.7 for the MR, and 5.8 for the SP.A and Groen. The Socialist, Liberal and Ecologist all support a dominant scenario to “come back to an institutional situation” before the 6th reform of the state. It is paramount to underline the absence of key differences between parties on both sides of the linguistic border. In fact, some Flemish parties are even more favorable to a scenario of Refederalisation than some French-speaking parties (for example, the SP.A and Groen compared to the PS and at Ecolo). The notable exception is found amongst the Flemish Christian Democrats’ MPs (CD&V presents a mean score of 4.5). This is the only non-nationalist Flemish party with a majority of MPs supporting Regionalisation. The standard deviations are substantial for all of these nine political groups, thus demonstrating internal heterogeneity on this issue.

19In conclusion, we observe that at the voter level, Flanders is more pro-devolution than Wallonia, albeit marginally. In fact, the most important and evident gap is between elites and voters, particularly in Flanders. Before the 6th Flemish political elites were found to develop much more radical positions regarding devolution than voters from their own community, albeit not anymore after the 6th reform of the state. On this matter, we have also demonstrated that political elites are strongly divided within communities (particularly between nationalist MPs and other MPs) and within parties (the standard deviation is generally high, where there are almost as many MPs supporting devolution as MPs defending Refederalisation of powers within the same political parties). In this context, where support for devolution is so diffuse across voters and elites, how can we explain that the issue triggered the longest political crisis that Belgium had ever faced? To answer this question, we must integrate strategic electoral/party interest with community factors. As theorized by previous scholars14, it is the consociational features of the Belgian political system that permit to highlight how and why Flemish political parties have entered in an intra-community party competition contributing to the escalation of inter-community conflicts. In other words, Flemish voters’ institutional preferences and identities were necessary but not sufficient conditions to explain the deep constitutional crises of the late 2000s and early 2010s.

4. Belgian consociationalism and its effects on intra- and inter-community party competition15

a) Actors forced to negotiate (1968-1995): the ‘system paralysis’ as default option

20The first waves of Regionalisation have been possible because both communities had ultimately agreed that the Belgian unitary state could not provide satisfactory outputs in its current form anymore. In a nutshell, the historic traditional cleavages that characterized Belgian politics – socio-economic left-right, church-state and centre-periphery – were roughly delimitated by the border between the North and the South of the country16. Flemish politics was dominated by the Church-State cleavage with a powerful Christian-Democrats party (CVP, nowadays CD&V) while the linguistic issue (centre-periphery cleavage) became increasingly salient because of the domination of the Francophone Bourgeoisie17. Therefore, demands raised in Flanders over the 20th century to claim more self-rule autonomy in policy areas such as education and the use of language. Although the church-state cleavage was also present in Walloon politics, the socio-economic cleavage was dominant with a powerful Socialist party (PS) due to the development of the industrial sector. With the decline and the deterioration of the economy in the 1960s, Walloon political elites sought to gain more autonomy and control over their own industrial apparatus. Overall, both communities had a common interest to reform the Belgian state, even though their motivations as well as institutional designs for granting self-rule autonomy differed. Walloon political elites requested territorial autonomy to deal with their declining industry, while Flanders claimed powers to develop their own policy regarding personal policy areas (such as language and education). Therefore, two types of sub-state entities were created: ‘Regions’ for economic and territorial matters and ‘Communities’ for personal matters.

21In addition, new procedures were implemented to ensure that none of the two communities could dominate the other at the federal level. It mostly reflected the French-speaking political elites’ fear of Flemish domination on national politics due to their larger demographic weight and representation in the national parliament, as well as their economic success. Therefore, three power-sharing mechanisms were constitutionally entrenched in 1970: (1) linguistic parity in the government; (2) special majority requirements to pass legislations on Regionalisation reforms (simple majority in each language group of the national parliament in addition to the overall required two third majority); and, (3) the creation of an alarm-bell procedure which allows one community to delay – and in practice to veto – any legislation that is contrary to its interests18.

22While these mechanisms give virtually total veto power to each community, in practice political parties from both sides were forced to negotiate and find agreements. This explains why the successive waves of Regionalisation until the early 1990s albeit reached at the climax of a long political crisis. According to Jans, who compared the functioning of the Belgian decision-making during the 1960-1989 with Canada, ‘forced negotiation’ must be explained by the cost of the default option (no agreement): a system paralysis. Absence of agreement on a new state reform “entails a broad and generalised blockage of the wider decision-making processes”19. Furthermore, a generalised blockage at the national level had direct implications for the functioning of the newly established sub-state institutions. Before the first direct elections of 1995, national MPs served in these institutions with a dual mandate20. In case of anticipatory federal elections, sub-state institutions would also be suspended. Therefore, “the entire political class focuses on the negotiations between the linguistic groups, which means that no more substantive political decisions can be made in any other policy field”21. The default option forced Flemish and Francophone political elites to find compromises, which often led to creative political arrangements: agreeing to disagree, log-rolling, splitting the difference, waffle-iron policy, asymmetrical constructions22.

b) From ‘business as usual’ to adjustment to the new rules of the game (1995-2014)23

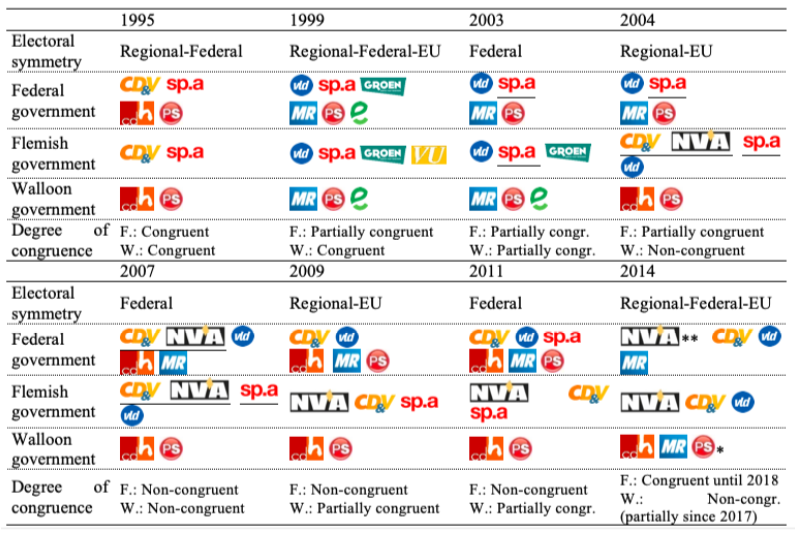

23The direct elections of the sub-state assemblies in 1995 had initially not altered the rules of the games in the short term. The regional and federal elections took place on the same day, which mostly nationalized the electoral campaign24. The incumbent Prime Minister Dehaene – father of the fourth reform of the state of 1993 – managed to conduct once again a cabinet with Socialists and Christian-Democrats (identical to the 1992-1995 cabinet). Although the sub-state entities had the constitutional autonomy to create their own coalitions, political parties under Dehaene’s leadership replicated the former practices of the pre-federal era. They formed symmetric and congruent coalitions at regional levels once the federal coalition was formed. On the one hand, each party of the same ideological party family joined the federal coalition in a perfect symmetry (i.e. Socialists and the Christian-Democrats from both communities). On the other hand, congruent coalitions were formed at the regional levels replicating the federal cabinet (see table 1). This strategy can be explained by the fact that the federal electoral arena remained the apex of the Belgian politics at that time. Furthermore, political elites who were negotiating had never experienced the direct election of sub-state institutions. They had been socialized in the mere federal politics where symmetry and congruence were the norm. Finally, symmetric and congruent coalitions empowered political parties’ control over inter-governmental relations between regional and federal arenas.

24 The 1999 regional, federal and European elections presented important electoral evolutions. The Flemish and Francophone Christian-Democrats deeply suffered and were, therefore, not anymore in a position of taking leadership. On the other hand, the Flemish Liberals (Open VLD) snatched an electoral win at federal elections (but not at the regional elections) which was just enough to allow Guy Verhofstadt to take the lead as the future Prime Minister. The Socialists in Wallonia maintained their first position while the exceptional results of the Greens allowed them to claim a position in the new federal coalition. At the regional level, the leading position of the Flemish Christian-Democrats gave them – in theory – the right to take the lead to form the regional cabinet. However, they considered that it was not a strategic card to play given their electoral situation. Overall, a federal cabinet with the Liberals-Socialists-Greens was first created (the so called ‘rainbow coalition’), which was then replicated at the regional levels. It must be noted that only political parties’ desire to form symmetric and congruent coalitions explains the inclusion of the Francophone Greens in the Walloon government. Indeed, the Liberals and Socialists had already a safe majority without them. Overall, the only exception to this perfect congruence was the inclusion of the VU (a Flemish ethnoregionalist party) at the regional level. They were mathematically necessarily to avoid the inclusion of the both ethnoregionalist and xenophobic party Vlaams Belang25.

25The first desynchronization of elections took place with the 2003 federal and 2004 regional elections, which started to alter the rules of the game. In 2003, Prime Minister Verhofstadt renewed his federal cabinet (a ‘purple’ coalition with Liberals and Socialists), but without the Greens that suffered a severe loss in the federal elections. This created another case of (partial) incongruence since the regional cabinets created in 1999 (Socialists-Liberals plus the Greens) were meant to continue until the next regional elections (see table 1). At the 2004 regional election, electoral results did not allow Socialists and Liberals to replicate a purple coalition in Flanders. The Flemish Christian-Democrats (CD&V) who were in the opposition at all levels since 1999 became eager to return to office. Having formed an electoral alliance with a former branch of the ethnoregionalist Volksunie – the N-VA – the CD&V took the lead to form the Flemish regional cabinet. In Wallonia, the Socialists decided to expel the Liberals from their regional coalition to form a cabinet with the Francophone Christian-Democrats (cdH). For the first time, major parties from both communities were in the opposition at one level, while being in the cabinet at another. Incongruence was even more salient in Flanders where the first party (CD&V) held furthermore the Presidency of the Flemish regional coalition26.

26These coalition incongruences, coupled with the features of the Belgian consociative system, started to trigger intra-community party competition while escalading inter-community conflicts. Indeed, “[t]he CD&V party leader Yves Leterme and Flemish Prime Minister carefully crafted an image of a regional government and its Prime Minister ‘governing well’. The opposition role at the federal level was put on a lower key, with actually the same baseline: ‘good governance is what we do (in Flanders), while the federal level performs badly (without us)’. When the 2007 federal election campaign started building up in 2006, the CD&V maintained this strategy as long as possible. It wanted obviously to return to power at the federal level and to beat both Liberals and Socialists”27. The so-called ‘BHV issue’ (concerning the borders of an electoral and judiciary district populated by a French-speaking majority on Flemish territory) was politicized as a major community conflict during the 2007 federal campaign. Unable to settle the question during the legislature, Verhofstadt’s cabinet decided to ‘freeze’ the issue and not discuss it anymore. The CD&V, in the Federal opposition at that time, heavily criticized this decision and argued that only the ‘good governance’ style they developed at the regional level would allow to settle the issue once and for all.

Table 2: Electoral cycles and coalition formations at regional and federal levels

Note: Electoral alliances were underlined. Partial congruence corresponds to a surplus-party at one level, whereas non-congruence corresponds to different parties across levels. * The MR replaced the PS in the Walloon government in July 2017. ** The N-VA quit the federal government in December 2018.

27Overall, these events increased the competition between Flemish parties during the 2007 federal campaign where each of them sought to emerge as the ‘best’ party able to solve the issue. Furthermore, being in an electoral alliance with the ethnoregionalist N-VA enhanced CD&V’s focus on community issues and the need for a new reform of the state. In the meantime, on the other side of the border, Francophone parties were firmly opposed to further regional autonomy, clamming that major reforms have been recently adopted (in 1993 and 2001). In addition, the Francophone ethnoregionalist party FDF which ran in alliance with the Francophone Liberals and defending the interest of the French-speaking voters in the BHV district vigorously opposed Flemish solutions to split the district. Ultimately, this caused the 2007-2008 political crisis.

28The drivers of the 2010-2012 political deadlock were similar. As no agreement on a state reform was found after the 2007-2008 crisis, the successive 2009 regional and 2010 elections amplified both the inter-community and intra-community competition in both party systems, focusing on which party would be the greatest defender of Francophone voters’ interest and the most autonomous Flemish party. In Flanders, competition increased even further once the N-VA was not anymore in an electoral alliance with the CD&V and proved to be a serious electoral competitor on its own after the 2009 regional elections. This strategy proved successful insofar their strong regionalist campaign was accompanied by a support for further autonomy devolution among Flemish citizens, as shown previously in Figure 1. Furthermore, support for more regional autonomy increased even in Wallonia. Probably not because they approved the campaign of the N-VA but because they perceived the long political crisis on the federal level as an argument for handling more competences on the regional level.

29The diametrically opposed positions emerging from the Flemish and Francophone party systems were caused by the new rules of the asymmetrical coalition game. Some parties in the regional cabinet blamed the federal cabinet where they did not serve and vice-and versa. The consociational nature of the Belgian electoral system reinforces this tension even more. Indeed, almost all regional and national Flemish representatives are elected by Flemish voters only, while the same is true for their Francophone counterparts28. Therefore, there are almost no centripetal electoral incentives for candidates and political parties to adopt cross-community positions during the campaign. On the opposite, as stated by Caluwaerts and Reuchamps29 “all political parties, not only the regionalist parties, were competing for electoral support on their side of the linguistic divide. Appealing to regionalist feelings thus became a strategy for gaining power in the federal government”. While congruence had previously allowed parties to be the main platforms to manage inter-governmental relations (easing tensions between levels), coalition incongruence, on the opposite, caused radicalization of positions between parties – both within and between language groups. While the first parliamentarians serving in the 1995 sub-state legislatures were mostly former national parliamentarians30, the Flemish and Walloon Parliaments have developed their own regional political class, which has become increasingly distinct from their federal counter-part31. As demonstrated by two recent MP surveys, the territorialization of politics favored the development of regionalist demands for sub-state elites and thus increased competition within parties32.

30Last but not least, incongruence does not only explain the emergence but also the persistence of community tensions. Indeed, in comparison to previous negotiations of state reforms (see section on the 1968-1995 period), the very nature of the default option has changed. While the absence of agreement previously entailed a total paralysis of the Belgian decision-making system (at all levels), the default option is now a single policy paralysis. This dramatically reduces the cost of no agreement as observed during the 2007-2008 and 2010-2012 political crisis. While the federal negotiators were struggling to settle the community conflicts, regional elites could pursue their own policy agenda with limited interference. Sub-state institutions cover an extensive scope of powers with robust fiscal resources. As Hooghe33 pointed out, powerful Belgian sub-state entities coupled with the existence of European decision-making contribute to explain the absence of the national government (for a small state such as Belgium). As a matter of fact, the pressures to find an agreement – and thus to form a federal cabinet – became increasingly more external than internal. The international financial markets started to cast doubts on Belgium’s budget exposure as the negotiation dragged on. Finally, in December 2012, eight political parties (Christian-Democrats, Liberals, Socialists, and the Greens from both linguistic sides) reached an agreement for a sixth state reform, without the support of ethnoregionalist parties.

31In 2014, after the sixth reform of the state being largely implemented, the ethnoregionalist N-VA entered the federal government for the first time in the party history (with exception to when they were in alliance with the CD&V). However, in order to be taken-up in the centre-right Michel I government (which was peculiar insofar it only involved one Francophone party, the MR of prime-minister Charles Michel), their promise had been to focus on socio-economic issues rather than on communitarian questions. Coupled with the symmetry of the Flemish side of the government, this allowed the coalition to survive most of its term rather stably. In December 2018, however, the N-VA quit the government (which went on as minority cabinet Michel II) six months before the next general election because of disagreements on the Federal cabinet’s stance towards the UN Migration Pact. From then on, the coalition asymmetry allowed the party to bring back communitarian questions to the agenda again. But in doing so, it was quite isolated among Flemish parties (with exception of the VB) because even the CD&V (the formerly most regionalist traditional party) declared a further state-reform to be postponed to the following legislature. This prevented a potential consociational deadlock to come up again.

32The 2019 elections, however, have provided the country with another difficult puzzle for forming a federal government. Despite slight losses, both socialists in Wallonia (PS) and ethnoregionalists in Flanders (N-VA) have kept their electoral strength. Given the success of extremists parties (left-wing in Wallonia, right-wing in Flanders), PS and N-VA are mathematically inevitable to form a cabinet that has a majority in both language groups34. If both cannot agree to govern together because they share only little common political ground, it might come to another federal government lacking the support of either language group (a practice that has increased in the last years since the Di Rupo government was only supported by a minority of Flemish MPs, while the Michel government was only supported by a minority of Walloon MPs). In addition to the lacking perceived legitimacy among citizens, such a government would again be very prone to the adversial party political dynamics that we described above. In times where Flemish and Walloon citizens express coherently different political votes, the consociational features of the Belgian federation create hence just as much political deadlock as when elites of both groups disagree on question of autonomy devolution. This deadlock is furthermore used by Flemish regionalists as a major argument in favour of further competence devolution because it would reduce the number of policy areas on the federal level on which disagreements can arise. If the remaining Flemish and Walloon parties do not show that these disagreements can be reasonably overcome, regionalists might obtain what they want in the end.

Discussion and conclusion

33Despite Flanders is often presented as a handbook example of strong regionalism, the organization of a referendum on Flemish independence has never been on the political agenda. This article explained the reasons for the absence of a self-determination referendum in Flanders and showed that, since the 2000s, the omnipresence of the self-rule issue at the top of the political agenda is not a direct response to regionalist demands of Flemish voters or the Flemish political class. Instead, it is the consociational features of the Belgian political system that enhance intra-community party competition and contribute to the escalade of inter-community conflicts. Which mostly explains the deep constitutional crises of the late 2000s and early 2010s. In this context, we can better understand why Flanders independence is supported neither by a majority of the population (9.5 percent), nor its representatives (except those belonging to one of the two regionalist parties, N-VA and VB). At the same time, one might wonder what the future of Belgian federalism is?

34The 6th state reform in 2014 has entrenched the resynchronization of regional, federal (and European) elections as an attempt to restore congruent coalitions and ease community tensions. The effects on the 2014 joint elections were, however, mixed. Firstly, political parties are still learning the new rules of the game. In 2014, the Francophone Socialists ultimately decided to renew their coalition with the Christian-Democrats at the regional level (before the latter ejected them in 2017), seeking to be subsequently one of the key components of the federal cabinet. They were indeed arithmetically and politically necessary to form a majority in the French-speaking group of the federal parliament. However, the Francophone Liberals – against incredible odds – decided to join as only Francophone party a centre-right coalition with the Flemish Christian-Democrats, Liberals and the N-VA. This was a unique configuration since the federalization of the country. Secondly, despite N-VA’s decisive electoral victory (obtaining 37 percent of the seats of the Flemish group in the federal parliament), it accepted to join a federal cabinet without further constitutional reforms (the absence of majority in the Francophone group of the federal parliament made it impossible). They argued that the exclusion of the Francophone Socialists and the establishment of a centre-right cabinet at the federal level was a reform of the state in its own right.

35At present time, the N-VA has officially renewed its commitment of future participation to a federal cabinet without constitutional reforms if – and only if – Francophone Socialists remained excluded from a federal coalition. The fact that coalitions are congruent on the Flemish side can be expected to limit the potential blaming between regional and federal cabinets, at least concerning constitutional reforms, since the Francophone side will not be the one requesting further competence devolution.

36Yet the situation is uncertain. On the one hand, community conflicts could be avoided if Francophone Socialists do not participate in a federal cabinet. This is, however, a difficult position to maintain as they are still the largest party in the South (albeit in competition with the Francophone liberals). On the other hand, the N-VA – if they maintain their electoral leadership in Flanders – could be in a position of requiring a new reform of the state if the Socialists were invited to join a federal cabinet. In that case, the strategy of dragging on negotiations might prove fruitful considering the new default option (namely policy paralysis at the mere federal level). After all, since the 6th reform of the state in 2014, the regional budgets are now larger than the federal budget. If the future is hard to predict, the next 2019 joint elections will unquestionably be of great interest for the evolution of Belgian federalism. But contrary to other “hot” cases of strong regionalism such as Catalonia, Scotland or Quebec, a referendum on Flemish independence will certainly not be part of the electoral campaign.

Notes

1 Because regionalism is a process that entails political and cultural driving forces, regional and national identities as well as the strength of ethnoregionalist parties are among the core cultural and political expressions of regionalism, cf. Swenden, (W.), Federalism and regionalism in Western Europe: a comparative and thematic analysis, Basingstoke & New York, Palgrave, 2006, p. 14.

2 De Winter (L.), et Türsan (H.), Regionalist Parties in the European Union. London, Routledge, 1998. ; De Winter (L.), Swyngedouw (M.), et Dumont, (P.), ‘Party system (s) and electoral behaviour in Belgium: From stability to balkanisation’, West European Politics, vol. 29, n° 5, 2006, pp. 933-956. ; Hepburn (E.), ‘Small Worlds in Canada and Europe: A Comparison of Regional Party Systems in Quebec, Bavaria and Scotland’, Regional and Federal Studies, vol. 20, n° 4-5, 2010, pp. 527-544.

3 Deschouwer (K.), et Sinardet (D.), ‘Langue, identité et comportement électoral’, in Deschouwer (K.), Les voix du peuple: le comportement électoral au scrutin du 7 juin 2009, Brussels, Editions de l’ULB, 2010, pp. 61-80. ; Frognier (A-P.), De Winter (L.), et Baudewyns (P.), ‘Les Wallons et la réforme de l’Etat. Une analyse sur la base de l’enquête post-électorale de 2007’, PIOP Working Paper, Louvain-la-Neuve, University of Louvain (UCL), 2008, https://cdn.uclouvain.be/public/Exports%20reddot/piop/documents/PIOP_Les-Wallons-et-la-reforme-de-Etat.pdf (consulted on October 7th, 2018). ; Lachapelle (G.), ‘Identités, économie et territoire: la mesure des identités au Québec et la Question Moreno’, Revue internationale de politique comparée, vol. 14, n°4, 2007, pp. 597-612. Moreno (L.), ‘Scotland, Catalonia, Europeanization and the ‘Moreno Question’’, Scottish Affairs, vol. 54, n°1, pp. 1-21.

4 Dumont (H.), et Van Drooghenbroeck (S.), ‘Le statut de Bruxelles dans l’hypothèse du confédéralisme’, Brussels Studies, https://journals.openedition.org/brussels/469 (consulted on October 7th, 2018).

5 Swenden (W.), et Jans (M.), ‘‘Will it stay or will it go?’ Federalism and the sustainability of Belgium’, West European Politics, vol. 29, n°5, 2006, pp. 877-894.

6 However, we cautiously inform the reader that Francophone voters’ preferences in the PartiRep surveys are based on samples strictly developed in Wallonia (and not in Wallonia and Brussels as in ISPO-PIOP).

7 Swyngedouw (M.), et Rinck (N.), ‘Hoe Vlaams-Belgischgezind zijn de Vlamingen? Een analyse op basis van het postelectorale verkiezingsonderzoek 2007’, CeSO-ISPO Working Paper, Leuven, University of Leuven (KUL), 2008, https://soc.kuleuven.be/ceso/ispo/downloads/ISPO%202008-6%20Hoe%20Vlaams-Belgischgezin d %20zijn%20de%20Vlamingen.pdf (consulted on October 7th, 2018).

8 Erk (J.), et Anderson (L.), ‘The Paradox of Federalism: Does Self-Rule Accommodate or Exacerbate Ethnic Divisions?’, Regional & Federal Studies, vol. 19, n°2, 2009, pp. 191-202, here p. 191.

9 Erk (J.), et Anderson (L.), op.cit., p. 192.

10 Moreno (L.), op.cit.

11 For a full description of Belgian identities, cf. Deschouwer, (K.), De Winter (L.), Sinardet (D.), Reuchamps (M.), et Dodeigne (J.), ‘Les attitudes communautaires et le vote’, in Deschouwer (K.), Delwit (P.), Hooghe (M.), Baudewyns (P.), et Walgrave (S.), Décrypter l’électeur : Le comportement électoral et les motivations de vote, Louvain, Lannoo, 2015, pp. 156-173. For debates on the operationalization of identities in Belgium, cf. Deschouwer, (K.), De Winter (L.), Dodeigne (J.), Sinardet (D.), et Reuchamps (M.), The adventures of the 'Moreno question' in Belgium: methodological reflection. Paper presented at the 4th Conference on the Belgian State of the Federation, University of Liège, Belgium, 2016.

12 Dodeigne (J.), Reuchamps (M.), et Sinardet (D.), ‘Identités, préférences et attitudes des parlementaires envers le fédéralisme belge après la sixième réforme de l’État’, Courrier hebdomadaire du CRISP, vol. 33, n°2278, 2015, pp. 5-52.

13 Source: Dodeigne (J.), Reuchamps (M.), et Sinardet (D.), op.cit.

14 Caluwaerts (D.), et Reuchamps (M.), ‘Combining Federalism with Consociationalism: Is Belgian Consociational Federalism Digging its Own Grave?’, Ethnopolitics, vol. 14, n°3, 2015, pp. 277-295. ; Deschouwer (K.), 'And the peace goes on? Consociational democracy and Belgian politics in the twenty-first century', West European Politics, vol. 29, n°5, 2006, pp. 895-911.

15 This section draws on the analysis of Deschouwer (K.), ‘Coalition Formation and Congruence in a Multi-layered Setting: Belgium 1995-2008’, Regional & Federal Studies, vol. 19, n°1, 2009, pp. 13-35.

16 Cleavages were in fact cross-cutting communities to some extent but it would require extensive elaboration that this short chapter allows us to detail. For further information, cf. Deschouwer (K.), op.cit., 2006.

17 Sinardet (D.), ‘Territorialité et identités linguistiques en Belgique’, Hermès, vol. 51, n°2, 2008, pp. 41-148.

18 For more details, cf. Sinardet (D.), ‘Le fédéralisme consociatif belge: vecteur d’instabilité?’, Pouvoirs, revue française d’études constitutionnelles et politiques, vol. 136, n° 1, 2010, p. 21-35.

19 Jans (M.), ‘Leveled domestic politics. Comparing institutional reform and ethnonational conflicts in Canada and Belgium (1960–1989)’, Res Publica, vol. 43, n°1, 2001, pp. 37-58, here p. 44.

20 Except for the Brussels-Region Parliament in 1989 and for the German-speaking Community Parliament in 1974, but we concentre on the two most important groups that constitute the main component in community conflicts. Cf. Dodeigne (J.), et Renard (H.), ‘Les résultats électoraux depuis 1847’, in Bouhon (F.) et Reuchamps (M.), Les systèmes électoraux de la Belgique, Bruxelles, Larcier, 2018, pp. 675-700.

21 Caluwaerts (D.), et Reuchamps (M.), op.cit, p. 289.

22 Deschouwer (K.), op.cit., 2006, p. 906.

23 This section draws heavily on the comprehensive analysis of coalition formation in Belgium by Deschouwer (K.), op.cit, 2009.

24 Ibid., p. 19.

25 Ibid., pp. 20-21.

26 Ibid.

27 Ibid., p. 28.

28 For details, cf. Pilet (J-B.), ‘The adaptation of the electoral system to the ethno-linguistic evolution of Belgian consociationalism’, Ethnopolitics, vol. 4, n°4, 2005, pp. 397-411.

29 Caluwaerts (D.), et Reuchamps (M.), op.cit, p. 286.

30 Dodeigne (J.), ‘(Re-)Assessing Career Patterns in Multi-Level Systems: Insights from Wallonia in Belgium’, Regional & Federal Studies, vol. 24, n°2, 2014, pp. 151-171.

31 Dodeigne (J.), ‘Regionalism Does Matter but Nationalism Prevails. A Comparative Analysis of Career Patterns in Western Multi-Level Democracies’, Paper presented at the ECPR General Conference, University of Glasgow, 2015, p. 1-30.

32 Dodeigne (J.), Reuchamps (M.), Sinardet (D.), op.cit. ; Dodeigne (J.), Gramme (P.), Reuchamps (M.), et Sinardet (D.), ‘Beyond linguistic and party homogeneity: Determinants of Belgian MPs’ preferences on federalism and state reform’, Party Politics, vol. 22, n° 4, 2016, pp. 427-439.

33 Hooghe (M.), ‘Does Multi-level Governance Reduce the Need for National Government?’, European Political Science, vol. 11, n°1, 2012, p. 90-95.

34 In the Francophone language group, this is also the case because the Francophone christian-democrats (cdH) have excluded to enter the federal coalition following their severe electoral losses.