- Accueil

- Volume 20 : 2020

- Trente ans de dynamiques fédérales et régionales

- How dynamic federalism sheds new light on the Belgian federalism-confederalism debate

Visualisation(s): 13837 (10 ULiège)

Téléchargement(s): 0 (0 ULiège)

How dynamic federalism sheds new light on the Belgian federalism-confederalism debate

Table des matières

1. Introduction: the Belgian case for dynamic federalism

1Since 1970, the Belgian political system has been drawn in a continuous series of decentralizing state reforms. The fourth state reform officially turned the former unitary state into a federal state, which was recognized with so many words in Article 1 of the constitution. This did not bring things to order: even when the constituent had no mandate for constitutional state reform, a fifth state reform took effect outside the constitution, through special organic laws. After the sixth state reform of 2012-2014, the door to further reforms was locked once more. Yet, the 2019 election turnout, with an unparalleled rise for extreme parties and a more radical preference for the left on the Walloon side, and the right on the Flemish side, brought the Flemish-nationalist demand for a confederation back on the table.

2These developments, with a steady process that transformed the country from a unitary state into an ever looser multi-tiered system, turns Belgium into an ideal case for dynamic federalism. Dynamic federalism is a revisited theory of federalism, building on Friedrich’s idea of federalism as a process, but in a new form to accommodate contemporary forms of compound government in the current era.

3The theory of dynamic federalism is explained elsewhere in more depth and with reference to multi-tiered systems worldwide1. Here, the presentation of a theory of dynamic federalism is tailored to the specific case of Belgium. The research question for this paper is: what does the theory of dynamic federalism contribute to the Belgian (con)federalism debate? The relevance of the paper, however, is not limited to Belgium. The theoretical framework will reveal its relevance for other contemporary federalist systems.

4In what follows, I will briefly explain why old federalism theories are not able to grasp the type of contemporary federalist organizations of which Belgium stands model (Section 2). I will then sketch the contours of dynamic federalism (Section 3) before addressing the research question (Section 4), which brings us to the conclusion (Section 5).

2. Why traditional federal theory is inadequate to grasp the Belgian federation

2.1 Inadequate definitions of federal systems

5Belgian constitutionalists tend to define Belgium as a sui generis federation2. The reason is that the Belgian system is assessed against traditional definitions of federal systems, modelled on some classic types of homogeneous coming-together federations, such as the United Stated and Germany. Yet, as Erk and Gagnon observed, unique characteristics that are seen as sui generis “can acquire broader meaning in the comparative study of multinational federations”3. This is important, because it is the function of theories to categorize manifestations of a specific phenomenon so as to identify and understand common features and dynamics. If the theory is not able to categorize contemporary forms of state other than as ‘sui generis’ systems, then it is inadequate to serve its purpose4. The emergence of a separate ‘branch’ of federal theory under the names of ‘ethno-federalism’, ‘post-conflict’, ‘pluralist’ or ‘multinational federalism’ 5, shows the defeat of traditional theory to cover all types of federalism and to accommodate institutional responses to contemporary developments.

6In what is called ‘the Hamiltonian tradition’6, traditional federal theory distinguishes three types of forms of state – unitary states, federations, and confederations – according to defining institutional features. Scholars have developed different lists of institutional features to define a federal system. One of the authoritative lists, drawn up by Ronald Watts, requires (1) two orders of government acting directly on their citizens, (2) a formal constitutional distribution of legislative and executive authority and the allocation of revenue sources ensuring genuine autonomy for each order, (3) representation of regional views within the federal institutions, by preference in a federal second chamber, (4) a supreme written and entrenched constitution, requiring the consent of a significant proportion of the constituent units through assent of their legislatures or by referendum majorities, (5) an umpire in the form of courts or provision for referendums, (6) processes and institutions to facilitate intergovernmental collaborations7. Other defining properties are frequently added, such as second chambers8, or subnational constitutional autonomy9.

7If these are features that define a federation, then Art. 1 of the Belgian Constitution errs where it describes Belgium as a federal state. Belgium does not have two orders of government that act directly on their citizens with legislative authority, but three: the federal government, the Communities and the Regions. Amending the constitution does not require the consent of the federated entities or referendum majorities. It does require a two third majority in the Senate, but this was turned into a chamber of the sub-states long after the constitution proclaimed Belgium to be a federal state. Still today, not all federated units are adequately represented in this chamber, and its powers are so few that it is unable to give voice to the regional views in federal decision-making10. Also, the federated units do not have prominent powers to adopt their own constitution11.

8Yet, this does not make Belgium the outlier. In fact, few systems show all the properties demanded by traditional theory. The reason is that under the Hamiltonian approach, those institutional features are identified that are shared by a “small number of historic prototypes that serve as model federal systems”12. These old-school models have two features in common: they are mono-national systems, and they were established after the unification of formerly independent states or colonies13. However, a theory exclusively based on these models, disregards common characteristics of new models – for example, residuary powers with the central authority, or no or underdeveloped subnational constitutional autonomy. Moreover, it is not able to deal with the most urgent challenges of contemporary multi-tiered systems – the same challenges Belgium is struggling with – which is how to accommodate multinationalism without fueling instability and separation threats14.

9This already points to some of the most problematic weaknesses of the Hamiltonian approach.

10First, it presents a circular reasoning fallacy: consensus about defining properties assumes a pre-existing definition of what federalism is. This implied definition gives us insight in the characteristics of specific federations, rather than what federalism in its essence is about. As a result, traditional theory merely teaches us how to copy the design of a particular federal state (or the average of a set of particular states). More so: it shows us how to become this state the way it was organized at some particular moment. For example, Wheare’s model of dual federalism based on exclusive competences shifted when the US turned into a system built on the concurrent power paradigm15.

11These old-school models, with the US on top, have left a dominant mark on how contemporary scholars envisage the design of federations, yet are unable to grasp the needs, challenges and shape of contemporary multi-tiered systems. Still, these models, called ‘true’ or ‘mature’ federations, are presented as superior, whereas other compound forms of state are considered immature or incomplete16. Basically, traditional theory neglects the fact that institutional features – in new and old school models – are part of a package deal, rather than essential properties17. This is especially the case in Belgium: the current system did not result from a visionary and coherent plan developed by the founding fathers. Instead, it is a bric-a-brac with new elements added after each state reform, dependent upon what was possible in the political constellation of that moment. The result of this neglect is a fixation on specific instruments, which means that we are missing out on alternative and potentially more effective mechanisms and procedures. In Belgium, bicameralism was preserved on the pretext that this is what defines a federal state. However, executive-based institutions are more effective for securing subnational interests in federal decision-making18. This is especially the case if the second chamber is designed the Belgian way – not representative of the Communities and Regions in a first stage, and more representative but powerless after the sixth state reform.

12Finally, traditional theory, with its focus on the relations between one central and one subnational level of authority within the system, is not able to grasp the dynamics resulting from the embedment in a more global legal environment19. For example, Duchacek formulated ‘exclusive national control over foreign relations’ as a (controversial) yardstick, only to discover later that real life developments had made this criterion obsolete20. Traditional federal theory is unable to categorize global multilevel constructs such as the European Union, and neglects how such constructs influence power relations of central and subnational authorities within national compound systems21. At the same time, it fails to grasp the dynamics between supranational, national, regional and local levels of authority. Several systems – South Africa and Brazil to name but a few – expressly recognize local entities as a third order in a system of co-government22. This creates dynamics of its own. For example, it has been pointed out in the literature that local decentralization is sometimes used to weaken regional levels of government23.

2.2 Inadequate definitions of confederations

13The Hamiltonian approach leads to great variety of lists, to the point that scholars have claimed that defining federations is an impossible task24. By contrast, scholars are surprisingly firm and unanimous as to which properties define confederations. Confederations are treaty-based systems, composed of sovereign states, that take decisions on the basis of unanimity but do not act directly upon the people25. In other words: a confederation is simply an international intergovernmental organization – albeit, as some scholars emphasize, one that is not confined to only one goal26.

14Despite the consensus, this definition of confederations is as problematic as the definition of federations. The Belgian case is a perfect illustration. Belgium is usually described as a federal system with confederal traits27, due to the major language groups’ formal and informal veto rights in the federal decision making process. Apparently, then, there is a category in between the Hamiltonian federations and confederations, which traditional theory is not able to grasp. Moreover, as soon as the Flemish-nationalist party N-VA put confederalism on the political agenda, a highly topical debate arose on the definition of confederations. According to the N-VA, a confederation does not necessarily imply separatism28, whereas scholars, clinging to traditional theory, maintain that it does, since confederations imply the collaboration of sovereign states29. The academic view, then, expects a clear-cut constitutional moment – the act of separation – before the system can transform from one form of state into a very different one. This fails to grasp the dynamics that brought about a gradual shift from a unitary state to an ever looser multi-tiered system. Considering the N-VA’s proposal as a model of very decentralized federalism30, ignores the fundamental paradigm shifts inherent to that model. It is also unable to accommodate the Flemish Christian-democratic party CD&V’s argument for so-called ‘positive’ confederalism, which places emphasis on the sub-states but does not endanger the country’s survival. What use is a theory of federalism if it is not able to guide political debates on forms of state, decisive for the system’s future?

2.3 The Elazarian approach; the illusion of a way out

15To avoid the difficulties attached to defining federations, scholars often use a broad working definition31. This comes down to Elazar’s denotation of federalism as ‘self-rule plus shared rule’32. In Elazar’s approach, ‘federalism’ points to a political principle that organizes political systems on the basis of a constitutional diffusion of power among central and constituent governing bodies in such a way that the existence and authority of all is protected, through a combination of autonomy (self-rule) and joint decision making (shared rule).

16This broad definition has the advantage of “being sufficiently generic that no one can disagree, while at the same time providing a rough idea of what it is all about”33. The fact that ‘no one can disagree’, however, makes it methodologically unsound: science thrives on falsification. A definition that is this broad, turns federalism into “one of those echo words that evoke a positive response but that may mean all things to all men”34. It is, in particular, not helpful for the Belgian debate, as it is not sufficiently specific to identify at which stage the Belgian system is transformed to the point that it is a confederation, rather than a federation, in the absence of a separatist seizure. Moreover, since it covers a very broad set of multi-tiered arrangements, it is not able to capture the dynamics of transforming forms of state at all.

17Elazar, however, used the ‘self-rule, shared rule’ metaphor to catch federalism as a political principle, not for federations as a particular form of state. In fact, he identified a wide range of federalist arrangements, of which ‘federations’ are just one type35. This, however, brings us back to the problems identified when discussing the Hamiltonian approach. Also, it shifts the focus on a typology of institutional manifestations of the federal principle, thereby drawing us into debates over categorization, that leads us astray from the concrete political problems that federalism is expected to deal with36. In Belgium, this means that the focus on whether confederalism is a synonym for separatism, is an obstacle for discussing what really is at stake: how to organize the Belgian system in such a way that it can accommodate the different preferences of national groups while keeping these groups committed to the integrity of the system as a whole. Only if this proves impossible, separation becomes an issue that needs serious consideration.

3. Contours of a theory of dynamic federalism

3.1 Friedrich’s federalism as a process as a starting point

18A dynamic approach to federalism dates back to Friedrich, who represented forms of state on a sliding scale between two extremes, complete unity and complete separateness37. In his theory, federalism is a process that may go either direction, towards joint arrangements, or towards differentiation38. This dynamic view allows for institutional diversity and is able to accommodate new trends.

19At the same time, the theory has important weaknesses. It was criticized for its vagueness as to how to identify a federal system and as to how process and structure are related39. Friedrich draws no sharp line between forms of state. All depends on the balance between unity and differentiation40, but no indication is provided as to what this balance entails exactly. Also, the impression arose that federal organisations are the endpoint of the process41, which ignores the fact that fragmenting systems such as Belgium may continue to devolve, even after they have become federal organisations. This way, it underestimates the risk that this process may lead to the dissolution of a political system. Finally, the gliding scale gives the impression that federalism is merely a matter of degree of centralisation or decentralisation. This has been picked up in the literature on decentralisation, but debates have remained on how federalism (as the institutional arrangement of an entire system) relates to decentralisation (as a degree of autonomous powers)42. More recently, the focus on dynamics of federalism has returned in federalism studies to examine how federal systems adapt to new circumstances and to respond to societal problems43. Yet, what is still missing is a snapshot of the institutional framework against which change can be measured and compared.

3.2 A theory of dynamic federalism

20For these reasons, Friedrich’s theory of federalism as a process is only a starting point. The theory of dynamic federalism adopts the focus on dynamic processes, as well as the balance between unity and territorial diversity as the core of federalism. In this theory, distinction is made between federalism as a value concept, federalist organisations or, rather, ‘multi-tiered systems’ as political organisations, and federations as one of several forms of state.

21Diamond defined federalist organisations as the institutional expression of the tension between the units that want to remain small and relatively autonomous, and the system as a whole that wants to remain large and relatively consolidated44. To avoid confusion between federal systems and other forms of state, and to accommodate those systems that wish to distance themselves from the term ‘federal’, I will further use the term ‘multi-tiered systems’ (MTSs) for this kind of political organisations: systems with multiple tiers of government, that combine the central level with subnational entities that have public policy powers45. This is even broader than Elazar’s definition, as it also comprises mere administrative decentralized systems.

22Federalism as a value concept responds to the tensions that rise within such MTSs, by considering the search for a proper balance between the need for integration and territorial claims for differentiation as the essence of federalism. For Mueller, finding this balance is the key to success for MTSs46. In a theory of dynamic federalism, however, the notion of ‘balance’ differs in two ways. First, it is not the middle point on a continuum between centralization and decentralization, as it is usually conceived47. Instead, it points to the proportion of centralization on the one hand, and of cohesiveness on the other. Balance does not mean ‘equal proportions’ altogether, but ‘correct’ proportions to keep the system in a steady position. Each component can be given different value, as long as, following the definition of a federalist political organization, some core of autonomy and interdependence is secured. Consequently, balance does not imply immobility, as both King and Burgess claimed48: what is considered the optimal balance, can change over time. Hence, the question is not where the key to success lies for all federalist organizations, but what proportion of institutional cohesion and autonomy is optimal for a given society.

23For this purpose, the system will employ instruments to secure autonomy, as well as instruments to create cohesion. Autonomy is the ability of subnational entities to organise themselves, make their own decisions, and secure their interests in central decision-making. Cohesion aims at securing the integrity of the entire system, for example by voicing the general interest that transcends the separate territorial interests, by establishing instruments that further the creation of a common public sphere and inter-regional solidarity, or by advancing commitment of territorial representatives to the general interest. This ‘federal spirit’, i.e. the commitment to living together peacefully, in mutual recognition and respect, is regarded as a fundamental value, and a condition for success49. Yet, federal theory is too often concentrated on the degree of subnational autonomy (self-rule) and representation (shared rule). By contrast, the urgent question whether federalism can also help to maintain the cohesiveness of a (multinational) democracy, as posed by Gagnon and Tremblay50, is neglected. Shared rule, moreover, is most often regarded as a way to secure autonomy within federal decision-making, rather than as a means to build cohesion. There is a difference. For example, autonomy is best secured if the subnational entity has an individual veto right in federal decision-making processes, but the federal decision-making process is more cohesive if all subnational entities together have a collective veto right that requires them to enter into a dialogue.

24What this ‘balance’ between autonomy and cohesion entails, is context-bound. It depends on the purpose of the form of state, and societal, economic, political and geographical factors. For multinational MTSs, finding the proper balance is especially challenging because they endeavour to manage conflicts that are generated by distrust in the central government perceived as serving exclusive rather than inclusive interests51. What is important, is that (i) the ‘proper balance’ is a constitutionally defined and contested concept, that (ii) the balance between autonomy and cohesion is not a trade-off, because cohesion is not a synonym for centralisation, and (iii) the balance designed by constitutional law defines the form of state. I will explain these fundamentals briefly, as there is no room here to go into detail52.

Proper balance as a constitutionally defined and contested concept

25Constitutional arrangements will define what the constituent envisages as ‘the proper balance’. Usually, safeguards are institutionalized to protect this federalist arrangement. At the same time, the so-called ‘authority boundaries’ are continuously contested 53. In a theory of dynamic federalism, this is essentially so, because external conditions and changes in political preferences may change the idea of what a ‘proper balance’ is for a particular system. Contestation can take place outside of the constitutional boundaries, but it is also an inherent and crucial part of the institutional arrangement. Constitutions are conceived as providers of instruments that are capable of recalibrating power relations when new developments put at risk important values, such as efficient government, the survival of the state, or group identity. Such instruments – hubs for change – are necessary to address instability that occurs when the division of powers and resources in an MTS is no longer accepted as legitimate by political actors at the different levels54. The capacity to respond to change, then, is regarded as an important factor for the survival of MTSs.55 This is particularly the case in multinational states56, where the organisation of diversity through federal arrangements is simultaneously the device for stability and the seed for instability57.

The balance between autonomy and cohesion is not a trade-off

26Contestation creates dynamics, which means that MTSs continuously move in opposite directions. This movement, however, is not merely a movement between the left and the right end of a gliding scale, as described in the literature on de/centralisation. On a de/centralist gliding scale, systems move to the left, towards a centralist system, when power gets concentrated with the central authority, corresponding to an equal loss of autonomy of the subnational entities, and vice versa.

27Cohesion, however, is a more complex concept. A centralist system can develop instruments to bring territorial groups together in such a way that they transcend group interests, it can organize power sharing instruments in such a way that central decisions are the sum of group interests, or it can ignore territorial interests all together. In the first case the centralist system is also cohesive, in the last case it is not. This brings us to the categorization of forms of state.

28A closer look into the indexes will clarify this matter. The size of the index, with 32 tables, however, obliges me to refer to the book on ‘Dynamic Federalism’ for clarification. Meanwhile, the discussion under section 4.2. already gives a glimpse of what the indexes contain.

A categorization of forms of states based on the proper balance

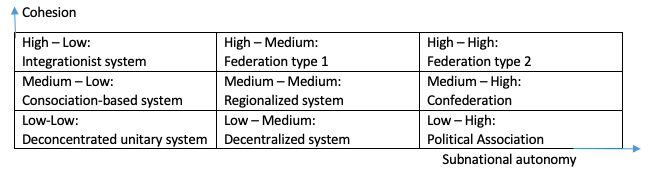

29In a theory of dynamic federalism, forms of state are defined as the sum of their scores on the cohesion index and the autonomy index. This means that this theory does not use a gliding scale to picture forms of state, but rather a checker board, where systems can move up or downwards, to the left or the right, or diagonally, as visualized in table 1.

Table 1. Forms of state

30Federations are systems that, ideally, score high on both cohesion and subnational autonomy (type 2), or at least high on cohesion and medium on autonomy (type 1). Cohesion is more important than autonomy, because the idea of partnership prevails as the ‘federal spirit’. Such ‘federal spirit’ entails a commitment to living together peacefully, in mutual recognition and respect, is regarded as a fundamental value of and a condition for the success of federal systems58.

31Confederations are systems that score high on the subnational autonomy dimension, and medium for cohesion. Political associations are systems that score low cohesion and high subnational autonomy. Intergovernmental international organisations would most likely fall under this category, but since sovereignty or independence is not a defining property, very loose political systems that are no international organisations may also get ranked under this label.

32The terms ‘integrationist systems’ and ‘consociationalist systems’ are borrowed from the power sharing literature. They represent two schools of thought with different recipes for accommodating ethnic groups in divided societies59. Centripetalists favor an integrative, cross-community model, whereas consociationalists argue for guaranteed group representation and prefer a model where the members of the governing bodies remain firmly rooted in their separate subgroup. The second model is considered less cohesive in table 1 because it encourages group mobilization. In divided societies, these sub-groups are not necessarily concentrated within a specific territory60. Considering that this scheme is only concerned with territorial divided MTSs, it only addresses those systems where the main groups largely overlap with territorial delineations.

33At which point a system is called a federation, a confederation, or any other form, depends upon how autonomy and cohesion are measured. For this purpose, autonomy and cohesion indexes must be developed, that examine institutional arrangements not in a search for defining properties, but for indicators that point to, respectively, autonomy and cohesion. So far, rough indicators for autonomy had already been developed61, but indicators for cohesion were absent. Elsewhere, I have developed a comprehensive set of indicators for both62. The set consists of 16 tables to measure autonomy and 16 tables to measure cohesion in the dimensions of status, powers and fiscal arrangements. Autonomy and cohesion tables in the dimension of status are linked with the different levels of authority: central and subnational constitutions, the legislative level, the executive level, international and supranational decision-making, and judicial organization. The indicators in the ‘powers’ dimension relate to the policy domains in which the authorities can act, i.e. the scope of their powers, to allocation techniques, and to political as well as judicial mechanisms to manage federalism disputes. Under fiscal arrangements, the cohesion index concentrates on equalization mechanisms and other measures to promote solidarity and partnership, whereas the autonomy index is mostly interested in revenue and spending powers and discusses subnational taxes, borrowing powers, shared tax revenues, conditional grants and fiscal discipline rules.

34For these measurements, cohesion is valued from a central perspective, and autonomy is approached from the angle of a specific subnational entity: what is measured is the extent of the autonomy that this subnational entity has in a political system. This means that a political system can be ranked in several categories at the same time, for example in asymmetrical arrangements, or when local and regional entities are compared. This way, the model captures the complexity that characterizes multi-tiered systems in practice.

4. What dynamic federalism contributes to the Belgian (con)federalism debate

35Dynamic federalism is an adequate theory to explain the Belgian case, for three reasons. First, it unravels semantic discussions about the meaning of confederalism, which is the subject of heated political and social debate. Next, it explains the continuous process of change. And finally, it raises the question of whether constitutional engineering is apt to turn the tide that brings Belgium to the brink of dissolution.

4.1 Confederalism: conceptual clarity

36As mentioned, heated debates arose over the concept of confederalism, and especially over the question as to whether this implies separatism. According to traditional theory, it does, since confederations are essentially forms of state where independent, sovereign states collaborate. Yet, the Flemish-nationalist N-VA maintains that it does not, and regards confederalism only as a step towards its goal of Flemish independence; and the Flemish Christian-democratic CD&V launched the notion of ‘positive confederalism’ within one state.

37In a theory of dynamic federalism, confederations do not imply independence. Confederations are systems that score high for autonomy and medium for cohesion. This means that the system predominantly invests in instruments that secure the autonomy of subnational entities, and is interested in consociationalist rather than integrationist power sharing instruments.

38In my book on ‘Dynamic Federalism’, I have developed the autonomy and cohesion indexes and applied them to Belgium. Lack of space obliges me to refer to the book for more detail. The results are presented in table 2. The indexes still have to be validated through academic debate and applications to several country studies. This is work in progress. Therefore I do not simply present the results in table 2 as a given, but will also refer to smaller but more established indexes for autonomy, and in particular to the Regional Authority Index (RAI) developed by Hooghe et al. and the axis developed by Requejo63, and to scholarship for cohesion. The Flemish Community is selected because, since the merger of Community and Region institutions, it is the largest subnational entity. For contrast, the small German-Speaking Community is selected as well.

Table 2. Autonomy and Cohesion in Belgium

|

Cohesion |

Autonomy FC |

Autonomy GSC |

|

|

Status |

0.39 |

0.75 |

0.61 |

|

Powers |

0.53 |

0.97 |

0.76 |

|

Fiscal Arrangements |

0.80 |

0.82 |

0.57 |

|

Overall |

0.57 (M) |

0.85 (H) |

0.65 (M) |

39Autonomy indexes show that the subnational autonomy grade for Belgium, and the Flemish Community in particular, is fairly high. In the RAI ranking, the Flemish Government has a score of 24 for autonomy, which is close to the scores of Québec in Canada (24,5), USA States (24,5) and Spanish Catalonia (23,5) and higher than the scores for Austrian Länder (23), although somewhat lower than the scores for Finish °Aland (25), Australian States (25,5), Swiss Kantons (26,5) or, in particular, German Länder (27). By contrast, the German-speaking Community has a score of only 14. In Requejo’s ranking, Belgium as a whole has an aggregate score of 25 on the axis of unitarianism/federalism and centralisations/decentralisation. This is higher than the scores of Austria (18,5) or India (23), close to the scores for Australia and Germany (26), although much lower than the scores for Switzerland (29), Canada (29,5) or the US (30). The ‘dynamic’ autonomy index is much more comprehensive and differentiating, but this index as well points to a high degree of autonomy. On a scale from 0 to 1, the Flemish Community has a score of 0.84 (high) and the German-Speaking Community scores 0.64 (medium). Here, the index shows that autonomy is highest in the dimension of powers. The index also allows us to measure constitutional asymmetry – in this case 0.20. Constitutional asymmetry points to the differences in autonomy with regard to status, powers and fiscal arrangements64. To appreciate this score, we need to compare with other asymmetrical systems.

40The cohesion index reveals a medium score overall, but a high score for fiscal arrangements and a low score for status. There are no other indexes to compare the results for cohesion, but we can refer to the literature that describes Belgium as a consociational system65 and that emphasizes confederal traits in federal decision making66, thereby referring to the units’ veto rights, rather than instruments that further cross-community commitment. This aligns with the index’s medium position for cohesion.

41This means that, at least from the standpoint of the Flemish Community, Belgium already is a confederation, or close to becoming one. This is different from the standpoint of the German-Speaking Community, which, in terms of dynamic federalism, comes down to a regionalized system. This means that Belgium is at the same time a confederation and a regionalized system, depending on the unit of analysis.

42If Belgium, at least with regard to the Flemish Community, already is a confederal system, or close to becoming one, the question rises how radical the N-VA proposal really is. For this, we need to take a closer look at the proposal as developed in its congress documents67.

43The model is not sufficiently elaborated to apply all 16x2 indexes, which means that we must limit ourselves to a general take. The document argues that the starting point for the organisation of Belgium should be that all powers reside with the subnational entities ‘Flanders’ and ‘Wallonia’ – Brussels and the German Speaking Community will have a different status. Flanders and Wallonia can decide to jointly exercise some of these competences when this is in the interest of each individual entity. For the central institutions, the suggestion is to organise a Belgian ‘Council’ and a Belgian government, similar to the EU Council and Commission. This means that the proposal opts for high autonomy and low cohesion – which brings the system in the category of a political association. The conclusion is that the N-VA proposal, indeed, implies a radical shift, bringing the Belgian system to a completely different category. This also shows that the N-VA understanding of confederalism, and the CD&V notion of ‘positive confederalism’, are two very different concepts. Using the term confederalism for both, only creates confusion.

4.2 Institutional processes for change

44Dynamic federalism emphasizes institutional change. Until now, this was also the approach taken in de/centralist studies, in a search for variables that push a system towards centralisation or decentralisation. These scholars were mainly interested in social, economic and political forces. By contrast, not much light has been shed on institutional instruments as drivers for change. Yet, most likely, constitutional provisions influence the conduct of political actors, and in this way cause their own processes of constitutional change68.

45A theory of dynamic federalism must therefore examine the instruments that are established as ‘hubs’ for changes in power relations. Among these instruments are the amendment procedures for constitutional revision, the technique for the allocation of powers, judicial and political instruments for the adjudication of power conflicts, and global governance.

4.2.1 Constitutional revision

46This perspective highlights the ‘staircase model’69 for constitutional revision, that points to a differentiated system with rigid instruments for fundamental changes in the constitution, a de-constitutionalized process through special and ordinary majority laws, and flexible instruments for more detailed amendments through (very limited) subnational constitutional autonomy.

47Some fundamental choices, such as the establishment of Communities and Regions as different subnational tiers, the status of these entities and their representation in federal institutions, are inserted in the constitution, under a rigid system that can be locked for an entire legislature. Still, the core of the federal institutional arrangements, such as the organisation of the Communities and Regions, powers and fiscal arrangements are de-constitutionalized in laws that give the major language groups a veto right, but leaves the German-Speaking Community aside. The result is that even if the constitution is locked, state reforms are still possible through organic (special majority) laws. If we view this from the perspective of dynamic federalism, based on indicators of autonomy and cohesion, what we see is that some important safeguards for autonomy are inserted in the constitution: the recognition of the Communities and Regions, their representation in the Senate, the veto rights and government parity for the two major language groups that largely overlap with the Flemish Community on one side, and the French Community and Walloon Region on the other, and the principle of exclusive competences.

48This way, autonomy, and a consociationalist rather than an integrationist arrangement, is well-entrenched. But even if the constitution is locked, it is still possible to make a shift towards more autonomy. In theory, ordinary and special majority laws can be used to make a shift towards more cohesion and less autonomy: for example, the enumeration of Community and Region competences can be reduced, or the fiscal arrangements can secure a financial distribution system based on enhanced solidarity. However, considering the constitutional framework and the dyadic and consociational process for change, in the hands of both major language groups that are accountable only to the electorate within their own language communities, it is more likely that the outcome of negotiations lead to more autonomy and less cohesion. This is what we have witnessed throughout six state reforms, which brought ever more autonomy, and no or little care for cohesive instruments.

4.2.2 Allocation of powers techniques

49As for the technique of power allocation, the main distinction opposes exclusive and shared powers70. in the case of exclusive powers, a matter falls within the ambit of either the central or the subnational authority, to the exclusion of the other. Typically, this is the institutional device for dual states71, in recognition of subnational autonomy and equality. Shared powers are either framework powers or concurrent powers. In the first case, central authorities can establish a general framework, and subnational entities can regulate the matter within the boundaries of the general framework. In the latter case, central authorities and SNEs both have the power to regulate a matter, in principle and in detail, but one level of authority – usually the central one – has priority.

50Shared powers are hubs for change, because federal interference changes the scope of subnational autonomy: subnational autonomy is inversely proportional to the extent to which central authorities use their powers. Most often, shared powers limit autonomy and promote a more integrated form of federalism72. Arguably, this effect can be mitigated through institutional devices73. For example, we can hypothesize that central authorities are less likely to invade in the policy domains of subnational entities or to act against their interests if subnational entities are effectively involved in the central decision making procedure. Also, the subsidiarity principle can be institutionalized to balance democracy and efficiency concerns to decide whether central interference is expedient or justified74. Some scholars expect the special justification requirement implied in this test to have a constraining effect in itself75, but most likely political safeguards combined with judicial enforcement are essential to prevent an over-centralising use of shared powers76.

51In Belgium, however, powers are allocated on the basis of exclusivity, with only very few exceptions. This is a more static way of competence allocation. Courts may still adjust the power balance by delineating the scope of these powers, but once this is settled, subnational autonomy is protected against interference by the central government. Exclusivity does not by definition guarantee subnational autonomy. For example, in Austria, where the bulk of competences lies with the central government77, it strengthens central dominance. Also, the use of an overarching clause that allows the central government to pre-empt state competencies, may transform the power distribution system, as occurred in the USA. But within a predominantly decentralized system, the exclusivity principle is a safeguard for subnational autonomy.

52Yet, exclusivity is not without side-effects78. It makes for a fragmented and obscure system of power allocation that is vulnerable for litigation. As no ‘watertight compartment’ is possible, efficient governance will require co-operation after all, to address the spill-over of policies over different areas79. And it prevents the central government from interfering to safeguard interregional solidarity or equality. This means that in Belgium, with its radical choice for exclusive competences, autonomy is preferred over cohesion in the allocation of powers, in a static manner.

4.2.3 Adjudication of power conflicts

53Judicial interpretation allows the court to continuously define and redefine vertical power relations80. Hence, even if the constitution is entrenched, courts may bring about shifts in power relations between central and subnational authorities. It is widely considered that courts in federal systems have a centralizing effect, shifting powers to the benefit of the central level. Some scholars regard this as an empirical truism81, others uplift it to a normative device82. In reality, not all courts have a centralising impact, and not all courts with a centralising impact have this effect in any given period83. Especially courts in centrifugal multinational systems tend to take a more balanced position84. In Belgium, an examination of all judgments on federalism disputes of the Belgian Constitutional shows that almost half of the judgments are in favour of the federal authorities, and half are in favour of the subnational Communities and Regions85.

54The question, then, is which variables turn courts into centralizing or balanced hubs for change. In Belgium, several factors explain the outcome86. Partly it is the effect of constitution-conform interpretation: any act of Parliament will be upheld as much as possible through constitution-conform interpretation and variety is explained by the fact that in one period more federal acts are challenged, and in another period more subnational acts. Other significant factors for Belgium, are the system’s basic structure – with every state reform that pushed the system towards more decentralisation, the Court took a less centralist stance – at least in disputes with political conflicts opposing two tiers of government. As in other constitutional courts, attitudinal effects play a more moderate role than in the US Supreme Court87. In Belgium in particular, the design as a power sharing court88 helps to take a balanced position89. Comparative analysis suggests that low representation of subnational entities in the selection of judges or the composition of courts furthers a more centralist stance90. In Belgium, political parties have a prominent role in the selection of the judges of the Constitutional Court. As parties in Belgium are region-based, this implies strong subnational involvement. Moreover, the language groups, which are central in the Belgian dyadic federation, are represented in the Court on the basis of language parity. The fact that parties are region-based probably also explains why the dependency-hypothesis – courts take a centralist position because their status, powers or budget depends upon the federal legislator91 – does not apply in Belgium. Finally, the Belgian Constitutional Court takes a significantly more centralist stance in salient cases92.

55However, courts are not the only institutions to adjudicate federalism conflicts. If non-judicial mechanisms take the upper hand over judicial adjudication of federalism conflicts, the question rises as to how this impacts on intergovernmental power relations.

56In Belgium, the Concertation Committee, characterized by linguistic parity and composed of as many federal as subnational government representatives, is the central body to deal with conflicts of interest. In reality, before a case is referred to the Concertation Committee, the matter is mostly resolved between the governing party leaders, or between ministerial cabinets, further away from the public spotlights93. This makes it difficult to examine the impact of political conflict resolving mechanisms in Belgium. However, the consociational design of the informal political negotiation suggest that conflicts are resolved in the interest of both major language groups. Only if this proves impossible, the conflict reaches the stage of the Concertation Committee, where a compromise is seldom reached. Where different preferences and distrust between language groups have a paralyzing effect, the usual outcome is a further transfer of powers to the subnational entities94.

4.2.4 Global governance

57Global governance can be a hub for shifts in the relationship between central and subnational powers in several ways.

58First, international treaties may articulate to the exercise of powers allocated to the subnational entities. Also, international obligations may induce central intervention in subnational policy domains95. In this case, more integrationist systems conclude the treaties without the involvement of subnational entities, or under an obligation to consult. The predominant view in those systems is that subnational interference is harmful to the national interest96. More balanced systems combine the involvement of subnational entities, most often through the Upper House. More confederal systems require the individual subnational entities’ approval. In the latter systems, subnational interests prevail over the national interest, as any subnational entity may veto a treaty that is considered beneficial to the entire nation97. The latter position can be found in Belgium, where Communities and Regions do not have a collective voice through the Senate, but an individual veto right, since all subnational Parliaments affected by the Treaty have to give approval98. This put Belgium in the world’s spotlight, when the Walloon and Brussels governments threatened to block CETA, the trade agreement between the EU and Canada.

59Next, the central government may transfer competences that range under the subnational entities’ sphere of powers, to international bodies. This way, subnational entities have to share their powers with international bodies, and may be put under the obligation to take action to implement international rules. For example, EU governance has been identified as an important constraint on the devolved entities, as many EU competences concern matters devolved to the subnational entities99. Here, the involvement of subnational entities is a two-trap system, implying, first, their involvement in the conclusion of the treaty on the transfer of powers, and, second, their involvement in EU law-making. The EU does not impose any procedure to give subnational entities a say – with, arguably, the exception under the Early Warning Mechanism that provides a subsidiarity check by national parliaments, where the parliaments’ votes are mandatory spread over both houses in bicameral systems100. Instead, with respect for the Member States’ varying structures101, it facilitates weak or strong subnational involvement. Again, distinction can be made between more centralist, balanced and confederal approaches, with Belgium as a prototype for the latter approach102. Communities and Regions have an individual veto right for the approval of EU treaties, as any other mixed treaty concluded by the federal government. Subnational ministers represent Belgium in the Council of Ministers if subnational matters are discussed, and in all cases, subnational and central level ministers meet beforehand to agree upon the Belgian stance, with a veto right for every actor103. If no consensus is found, Belgium will abstain in the Council of Ministers. In the Early Warning Mechanism, the Belgian Declaration n°51 applies, which states that in the Belgian legal order, the term ‘national parliaments’ in the EU treaties includes the subnational parliaments. According to a cooperation agreement104, each subnational Parliament can submit a reasoned statement and votes are cast in such a way that the positions of each federal or subnational legislative assembly are positioned next to each other, without fostering institutional dialogue105.

60Finally, an extra hub can be created in the form of an international court, which may not only shift power relations between the national member state and the international (or supranational) system of which it forms part, but may also impact upon the power relations between the central and subnational authorities within the member state. For example, the European Court of Justice undermined the Belgian system of power distribution by imposing the employment criterion to determine the locus of competence for a system of social care insurance instead of the usual residence criterion, for persons who had made use of their right of free movement. The Advocate General had even considered the use of the employment criterion in purely internal relations, but the ECJ toned this down to a mere suggestion106.

61In this case, an extra dimension is added to the debate on the factors that influence the position of the court, discussed above. For example, the question rises as to whether the European level, the national authorities and the SNEs have some control over the selection of judges and the organisation of the court, or only one or two of these levels of authority. Another question is whether all entities have equal access to the Court.

4.2.5 Can constitutional engineering turn the tide?

62A dynamic federalism approach highlights the devolving dynamics, and the acceleration of these dynamics, behind a country in a perpetual state of reform. Social, economic and political factors play an important role to this effect, with, for example, the absence of nation-wide political parties as a prominent explanatory variable. For constitutional lawyers, the question is whether institutional mechanisms also play a role, and, if so, whether constitutional engineering can steer dynamics. As Watts pointed out, institutions, once created, tend to channel themselves and shape societies107.

63The Belgian example shows that constitutional engineering is in any case capable of reinforcing devolving political dynamics. The driving force is not one particular instrument, but the entire system combined with political forces. For example, although the federal government with its language parity has been called an example of ‘integrated cooperation’108, in reality it is far from a cohesive body. Due to the electoral system and the regionalized political party landscape, holding political actors accountable to their own language community only, political parties are discouraged from reaching out to the other language community and accepting compromises. Where regional preferences are too divergent, deadlock is the inevitable result109. The preferred outcome, then, is further devolution, with the exclusivity principle encouraging further dispersion. In turn, far-reaching decentralization advances non-centralist judicial adjudication.

64Interestingly, political preferences do not (or no longer) seem to converge with social structure. In his book on ‘Explaining Federalism’, Erk convincingly show that institutional change mostly follows societal dynamics. However, this does not mean that institutional change cannot, in turn, impact on these dynamics. The author contends that the Belgian political institutions gradually changed in order to become congruent with the societal structure in terms of linguistic and cultural duality, and that “a satisfactory level of congruence” was attained in 1993 when Belgium officially became a federal state110. According to him, Flemings have since then been preoccupied with the contents of their policies more than with further state reforms111. Yet the author ignored a fifth state reform in 2001, which was carried out through special majority laws because the constitution, at that time, was locked against institutional reform. By neglecting the impact of institutions on societal dynamics, he did not foresee the sixth state reform in 2013 nor the subsequent confederal debate. As mentioned in the introduction, the outcome of the 2019 elections complicated the formation of a federal government, because of the unprecedented rise of extreme parties, a more driven preference for left-wing parties on the Walloon side and for right-wing parties on the Flemish side. Post-electoral research revealed that the division between north and south is a political divide rather than the reflection of a social dichotomy112. The different voting results reflected the different mixtures of (mostly regional) political parties that presented themselves to the voters at each side of the language border. However, in reality both Walloons and Flemings hold mainly centrist political preferences113. This suggests that institutional and political dynamics can be mutually reinforcing to the point that they surpass social cleavages.

65Given the fact that the population does not support separatism, the million dollar question is whether constitutional engineering can also turn the tide. The dynamic federalism theory, with its table on forms of state, clarifies that this would not necessarily impede on subnational autonomy, but that it requires investment in cohesive instruments. Table 2 shows that there is room for more cohesion especially in the categories of status and powers. A more detailed account of the cohesion index, presented elsewhere114, indicate that individual veto powers and the exclusivity principle in particular are responsible for reduced institutional cohesion. By contrast, parties that strive for (Flemish) independence will likely focus on institutions that have a high score for cohesion. The score is already low in the category ‘status’. In the category ‘powers’, the cohesion score for allocation principles stands out. A detailed picture115, however, shows that this is largely due to the jurisprudence of the Constitutional Court and is therefore more difficult for political actors to change. For these actors, ‘fiscal arrangements’ – the only category where the cohesion score outweighs the autonomy score - is the most promising avenue to perpetuate disintegration.

66Further elaboration of this theory and more country studies to test the indexes are needed to establish which instruments have most cohesive potential. Another question is whether political actors, caught in devolving dynamics, are willing and able to institutionalize cohesive instruments. In political circles, even moderate proposals to that effect, such as a federal election district for a proportion of seats116 or shared competences in social policy domains117 were received with little enthusiasm.

5. Conclusion

67In this paper, developments in the Belgian federal system were presented as a showcase to point out the weaknesses of traditional federal theory and to outline the contours of a (re)new(ed) theory of dynamic federalism.

68Traditional federal theory, with its static definition of federations and confederations, is incapable of grasping the dynamics that move the Belgian state towards the brink of dissolution. Dynamic federalism offers the tools, terminology and definitions (i) to explain processes of change instead of getting stuck in semantic debates of whether confederalism implies separatism or not, (ii) to build indicators to measure autonomy and cohesion, which will enable us to situate Belgium – in its current design, and in proposals for the future – in the checker board of forms of state, and (iii) to examine how, through constitutional engineering, we can accelerate or turn federal dynamics.

69The main question in this engineering exercise, is what balance we think is appropriate within the current social and political context. N-VA and Vlaams Belang are very clear as to their preference in that respect. If proposals for further state reform will indeed take effect, then it is time for all political parties to take a clear stance.

Notes

1 Popelier (P.), Dynamic Federalism. A New Theory for Cohesion and Regional Autonomy, Routledge, London, 2020. A more concise version will be published as a chapter in Delaney (E.) (ed), Handbook on the Law and Politics of Federalism, Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, forthcoming.

2 Alen (A.) en Muylle (K.), Handboek van het Belgisch Staatsrecht, Alphen aan den Rijn, Kluwer, 2011, pp. 196-197 ; Baeteman (G.), ‘Aspecten van het Belgisch federalisme – anno 1994-1995’, in Alen (A.) and Baeteman (G.), Publiekrecht Ruim Bekeken, Maklu, Antwerp, 1994, p.71 ; De Winter (L.) and Baudewyns (P.), ‘Belgium: Towards the Breakdown of a Nation-State in the Heart of Europe?’, Nationalism and Ethnic Politics, vol. 15, n° 3-4, 2009, pp. 286-289 ; Delpérée (F.), ‘La Belgique est un Etat fédéral’, Journal des Tribunaux, 1993, p. 638.

3 Erk (C.) and Gagnon (A.), ‘Constitutional ambiguity and federal trust: codification of federalism in Canada’, Spain and Belgium, Regional & Federal Studies, vol. 10, n°1, 2000, p. 109.

4 As Schütze (R.), From Dual to Cooperative Federalism. The Changing Structure of European Law, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2009, p. 3, reminds us: “the sui generis idea is not a theory. It is an anti-theory as it refuses to search for commonalities”.

5 Fleiner (B.) and Gaudreault-DesBiens (J.-F.), ‘Federalism and Autonomy’, in Tushnet (M.), Fleiner (T.) and (C.) (eds.), Routledge Handbook of Constitutional Law, Routledge, London, 2013, p. 144.

6 Pinder (J.), ‘Multinational federations. Introduction’, in Burgess (M.) and Pinder (J.) (eds), Multinational Federations, Routledge, London, 2007, p.2.

7 Watts (R.L.), Comparing Federal Systems, McGill-Queen’s University Press, Montreal, 2008, p. 7 ; Watts (R.L.), ‘The Federal Idea and its Contemporary Relevance’, in Courchene (T.J.) et al. (eds.), The Federal Idea. Essays in Hounour of Ronald L. Watts, McGill-Queen’s University Press, Montreal, 2011, pp. 15-16.

8 Burgess (M.), Comparative federalism. Theory and Practice, Routledge, London, 2006, p. 204.

9 Gardner (J.), ‘In Search of Sub-National Constitutionalism’, European Constitutional Law Review, vol. 4, n°2, 2008, p. 325 ; Fasone (C.), ‘What Role for Regional Assemblies in Regional States? Italy, Spain and the United Kingdom in Comparative Perspective’, Perspectives on Federalism, vol. 4, n°2, 2012, p. 176.

10 For an English account of the Belgian Senate after the sixth state reform, see Popelier (P.), ‘Bicameralism in Belgium: the Dismantlement of the Senate for the Sake of Multinational Confederalism’, Perspectives on Federalism, vol. 10, n°2, 2018, pp. 221-224 and 231-235.

11 In the parliamentary debates, it was called an ‘embryo’ of subnational constitutional power, see Annales House of Representatives, 1992-1993, 8 February 1993, n° 32, p. 1286; Parl. Doc. House of Representatives, 1992-1993, n° 725/6, 66. See further Berx (C.), ‘Een Grondwet voor de Belgische deelstaten ? “Lessen” uit het buitenland en de Europese Unie’, in Peeters (B.) and Velaers (J.) (eds.), De Grondwet in groothoekperspectief, Intersentia, Mortsel, 2007, pp. 239-256 ; Elst (M.), ‘De constitutieve autonomie: muizenstapjes, maar wel meer muizen’, in Alen (A.) et al. (eds.), Het federale België na de Zesde Staatshervorming, La Charte, Brussels, 2014 ; Judo (F.), ‘Constitutieve autonomie anno 2010: onmiskenbare stilstand of onderhuidse revolutie?’, in De Becker (A.) and Vandenbossche (E.) (eds.), Eléments charnières ou éléménts clés en droit constitutionnel, La Charte, Brussels, 2011 ; Nihoul (M.) and Bárcena (F.-X.), ‘Le principe de l’autonomie constitutive: le commencement d’un embryon viable’, in ibid. ; Popelier (P.), ‘The need for sub-national constitutions in federal theory and practice. The Belgian case’, Perspectives on Federalism, vol. 4, n°2, 2012, p. 58.

12 Gamper (A.), ‘A Global Theory of Federalism? The Nature and Challenges of a Federal State’, (German Law Journal, vol. 5, n°10, 2005, p. 1298.

13 Choudry (S.) and Hume (N.), ‘Federalism, devolution and secession: from classical to post-conflict federalism’, in Ginsburg (T.) and Dixon (R.), Comparative Constitutional Law, Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, 2011, p. 363; Stepan (A.), ‘Towards a New Comparative Politics of Federalism, Multinationalism, and Democracy: Beyond Rikerian Federalism’, in Gibson (E.L.) (ed.), Federalism and Democracy in Latin America, John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 2004, p. 39; Stepan (A.), ‘Federalism and Democracy: Beyond the US Model’, Journal of Democracy, vol. 10, n°4, 1999, pp. 20-21.

14 Gagnon (A.-G.) and Tremblay (A.), ‘Federalism and diversity: a new research agenda’, in Kincaid (J.), A Research Agenda for Federalism Studies, Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, 2019, p. 131 ; Requejo (F.), ‘Plurinational federalism and political theory’, in Loughlin (J.), Kincaid (J.) and Swenden (W.) (eds.), Routledge Handbook of Regionalism and Federalism, Routledge, London, 2013, p.34 and p. 38. See also Lecours (A.), ‘Federalism and nationalism’, in Kincaid (J.), op.cit., 2019, p. 142.

15 Schütze, op.cit., p. 94.

16 Sala (G.), ‘Federalism without adjectives in Spain’, vol. 44, n°1, Publius: the Journal of Federalism, p. 109 quotes the various adjectives that have been used to describe Spain as “something other, or even less, than a federation”: imperfect federalism, noninstitutional federalism, incomplete federalism, unfulfilled federalism and quasi-federation.

17 Jackson (V.C.), ‘Comparative Constitutional Federalism: Its Strengths and Limits’, in Gaudreault-Desbiens (J.-F.) and Gélinas (F.) (eds.), Le fédéralisme dans tous ses états, Bruylant, Bruxelles, 2005, pp. 148-151.

18 Palermo (F.), ‘Beyond Second Chambers: Alternative Representation of Territorial Interests and their Reasons’, Perspectives on Federalism, vol. 10, n°2, 2018, pp. 49-70.

19 Loughlin (J.), ‘Reconfiguring the nation-state. Hybridity vs. uniformity’, in Loughlin (J.), Kincaid (J.) and W. Swenden (eds), op. cit., p. 16.

20 Duchacek (I.), ‘Consociational Cradle of Federalism’, Publius: the Journal of Federalism, vol. 15, n°2, 1985, p. 45.

21 See Courchene (T.J.) et al. (eds.), op.cit., p. 24 for the trends toward multi-level federal organization.

22 Art. 40.1 South African Constitution; Art. 1 Brazilian Constitution. See Palermo (F.) and Kössler (K.), Comparative Federalism. Constitutional Arrangements and Case Law, Hart, Oxford, 2017, pp. 281-320 for this development.

23 Dickovick (J.T.), ‘Municipalization as Central Government Strategy: Central–Regional-Local Politics in Peru, Brazil, and South Africa’, Publius, the Journal of Federalism, vol. 37, n°1, pp. 1-25.

24 Kincaid (J.), ‘Editor’s Introduction: Federalism as a Mode of Governance’, in Kincaid (J.), Federalism, op.cit., p. xxi ; Palermo (F.) and Kössler (K.), op. cit., p. 36.

25 Palermo (F.) and Kössler (K.), op. cit., p. 35 ; Velaers (J.), Federalisme/Confederalisme… en de weg er naar toe, KVAB Press, Brussels, 2013, p. 14. See also Kincaid (J.), ‘Editor’s Introduction’, p. xxii – but see, by contrast, p. xxiii.

26 Palermo (F.) and Kössler (K.), op. cit., p. 35.

27 Maddens (B.), ‘La Belgique à la croisée des chemins: entre fédéralisme et confédéralisme’, Outre Terre, vol. 40, n°3, pp. 252-254 ; Pas (W.), ‘Confederale elementen in de Belgische federatie’, Tijdschrift voor Bestuurswetenschapoen en Publiekrecht, vol. 64, pp. 72-81 ; Rimanque (K.), ‘Réflexions concernant la question oratoire: y-a-t-il un état belge?’, in Dumont (H.) et al. (eds.) Belgitude et crise de l’état belge, FUSL, Brussels, 1989, p. 67.

28 See this model in N-VA, Congress paper, Verandering Voor Vooruitgang (2014) https://www.n-va.be/sites/default/files/generated/files/dossier/definitieve_congresbrochure.pdf. For a discussion: Maddens (B.), op. cit., 256-260.

29 Velaers (J.), op. cit. n. 25, pp. 22–23.

30 Behrendt (C.) and Vrancken (M.), Principes de Droit constitutionnel belge, La Charte, Bruxelles, 2019, p. 17.

31 Palermo (F.) and Kössler (K.), op. cit, p. 3. See further Law (J.), ‘How can we define federalism?’ Perspectives on Federalism, n°5, 2013, p. 115 for references to scholars that use broad or minimalist definitions for this reason.

32 Elazar (D.J.), Exploring Federalism, University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa, 1991 [1987], p. 12.

33 Palermo (F.) and Kössler (K.), op. cit.

34 Duchacek (I.D.), Comparative Federalism, Holt, Rinehart & Winston, New York, 1970, p. 190.

35 Elazar (D.J.), op. cit., 38-64.

36 Choudry (S.) and Hume (N.), op. cit., p. 359.

37 Friedrich (C.J.), Constitutional Government and Democracy: Theory and Practice in Europe and America, Ginn and Company, Cambridge, 1950 (3rd ed.), p. 190.

38 Friedrich (C.J.), ‘New Tendencies in Federal Theory and Practice’, Jahrbuch des Öffentliches Rechts, n° 14, 1965, p. 2 ; Friedrich (C.J.), Trends of Federalism in Theory and Practice, Frederick A. Praeger, New York, 1968, p. 177.

39 Birch (A.H.), ‘Approaches to the study of federalism’, Political studies, XIV, 1966, pp. 15-33, reprinted in Kincain (J.), Federalism, op. cit., p. 322 ; Burgess (M.), In Search of the Federal Spirit, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2012, p. 139.

40 Friedrich (C.J.), Man and his Government: An Empirical Theory of Politics, Mc Graw-Hill Book Company Inc., New York, 1963, p. 585.

41 Davis (S.R.), The Federal Principle: A Journey through Time in Quest of Meaning, University of California Press, Berkeley, 1978, pp. 173-178 with respect to the term ‘federalizing’.

42 For this discussion, see Dardanelli (P.), ‘Decentralization’, in Kincaid (J.), op.cit. n. 14, p. 107.

43 Benz (A.) and Broschek (J.), Federal Dynamics. Continuity, Change & the Varieties of Federalism, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2013 ; Colino (C.), ‘Introduction: the study of change in federations’, in Erk (J.) and Swenden (w.) (eds.), New directions in federalism studies, Routledge, London, 2010 ; Erk (J.), Explaining Federalism, Routledge, London, 2010.

44 Diamond (M.), ‘The Ends of Federalism’, Publius: the Journal of Federalism, vol. 3, n°2, 1973, p. 130.

45 Agranoff (R.), ‘Power Shifts, Diversity and Asymmetry’, in Agranoff (R.) (ed.), Accomodating Diversity: Asymmetry in Federal States, Nomos, Baden-Baden, 1999, p. 12-13 ; Popelier (P.) and Sahadžić (M.), ‘Linking Constitutional Asymmetry with Multinationalism. An Attempt to Crack the Code in Five Hypotheses’, in Popelier (P.) and Sahadžić (M.), Constitutional Asymmetry in Multinational Federalism, Palgrave MacMillan, New Yori, 2019, p. 4.

46 Mueller (S.), ‘Federalism and the politics of shared rule’, in Kincaid, op. cit. n. 14, p. 162.

47 E.g. Mueller (S.), Theorising decentralization, ECPR Press, Colchester, 2015, p. 7 where he sees centralized/decentralized states as the desired empirical outcome of federalism as an ideology.

48 King (P.), Federalism and Federation, Croom Helm, Kent, 1982, p. 56-68; Burgess (M.), Comparative federalism. Theory and Practice, Routledge, London, 2006, pp. 45-46.

49 Burgess (M.), op.cit. n. 39, p. 322. See also Friedrich (C.J.), Trends of Federalism in Theory and Practice, op. cit., pp. 175-176.

50 Gagnon (A.-G.) and Tremblay (A.), op. cit., pp. 131-132.

51 See Steytler (N), ‘Non-centralism in Africa: in search of the federal idea’, in Kincaid (J.), op. cit. n. 14, pp. 176-177.

52 For more detail, see Popelier (P.), op. cit., n. 1, pp. 50-57.

53 Bednar (J.), ‘Federalism theory: the boundary problem, robustness and dynamics’, in Kincaid (J.), op. cit. n. 14, p. 27.

54 For this definition of stability see Behnke (N.) and Benz (A.), ‘The Politics of Constitutional Change between Reform and Evolution’, Publius: the Journal of Federalism, vol. 39, n°2, 2009, p. 215.

55 Burgess (M.) and Tarr (G.A.), ‘Introduction: Sub-national Constitutionalism and Constitutional Development’, in Burgess (M.) and Tarr (G.A.), Constitutional Dynamics in Federal Systems. Subnational Perspectives, McGill-Queen’s University Press, Montreal, 2012, p. 3.

56 Steytler (N.) and Mettler (J.), ‘Federalism and Peacemaking: A South African Case Study’, Publius: the Journal of Federalism, vol. 31, n°4, p. 93. See also Lecours (A.), ‘Federalism and nationalism’, in Kincaid (J.), A Research Agenda for Federalism Studies, op.cit., pp. 143-144.

57 On the debate of whether ethnic federalism is a device for success or failure, see Choudry (S.) and Hume (N.), op. cit., pp. 356-357, pp. 364-372 and Palermo (F.) and Kössler (K.), op. cit., pp. 101-105.

58 Burgess (M.), op. cit. n. 39, 322. See also Friedrich (C.J.), Trends of Federalism in Theory and Practice, op. cit. n. 36, pp. 175-176, Livingston (W.S.), Federalism and Constitutional Change, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1956, p. 316 and Sahadžić (M.), Asymmetry, Multinationalism and Constitutional Law, Routledge, London, 2020, p. 216.

59 For an effort to overcome this dichotomy, see Cochrane (F.), Loizides (N.) and Bodson (T.), Mediating Power Sharing, Routledge, London, 2018, pp. 2-4, pp. 105-108.

60 As Livingston (W.S.), op. cit., p. 2 pointed out, this is what distinguishes federalism from “functionalism, pluralism or some form of corporatism”.

61 Several indexes have been developed, but the most comprehensive one, so far, is the Regional Authority Index (RAI): Hooghe (L.), Marks (G.), Schakel (A.H.), Niedzwiecki (S.), Chapman Osterkatz (S.) and Shair-Rosenfield (S.), Measuring regional authority. A postfunctionalist theory of governance. Volume 1, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2016.

62 Popelier (P.), op. cit., n. 1, pp. 87-189.

63 The most recent ranking for the RAI, in 2016, can be found on this website: https://www.arjanschakel.nl/index.php/regional-authority-index. For Requejo’s axis and the ranking of 19 systems, see Requejo (F.), ‘Federalism and democracy. The case of minority nations: a federalist deficit’, in Burgess (M.) and Gagnon (A.) (eds.), Federal Democracies, Routledge, London, 2010, pp. 275-298.

64 Sahadžić (M.), op. cit., n. 45.

65 Deschouwer (K.), ‘And the peace goes on? Consociational democracy and Belgian politics in the twenty-first century’, West European Politics, vol. 29, n°5, pp. 895-911 ; Peters (B.G.), ‘Consociationalism, corruption and chocolate: Belgian exceptionalism’, West European Politics, vol. 29, n°5, pp. 1079-1092.

66 See supra n. 27.

67 N-VA, Verandering voor vooruitgang, Antwerp 2014, https://www.n-va.be/sites/default/files/generated/files/dossier/definitieve_congresbrochure.pdf, at pp. 5-6.

68 Simeon (R.), ‘Constitutional Design and Change in Federal Systems: Issues and Questions’, Publius: the Journal of Federalism, vol. 39, n°2, 2009, p. 242.

69 Cochrane (F.), Loizides (N.) and Bodson (T.), op. cit., pp. 66-67.

70 Hueglin (T.O.), ‘Comparing federalism: Variations or distinct models?’, in Benz (A.) and Broschek (J.), Federal Dynamics. Continuity, Change & the Varieties of Federalism, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2013, p. 29.

71 Palermo (F.) and Kössler (K.), op. cit., p. 129.

72 Swenden (W.), Federalism and Regionalism in Western Europe, Palgrave MacMillan, New York, 2006, p. 50-57.

73 See for more detail: Popelier (P.), ‘Exclusive Powers and Self-governed Entities: a Tool for defensive federalism?’, in Requejo (F.) (ed.), Defensive Federalism, Routledge, London, forthcoming.

74 Gamper (A.), op. cit., p. 1300 ; Vandenbruwaene (W.), ‘What Scope for Subnational Autonomy? The legal enforcement of the principle of subsidiarity’, Perspectives on Federalism, vol. 6, n°2, p. 51.

75 Gardbaum (S.), ‘Rethinking Constitutional Federalism’, Texas Law Review, n°74, 1996, p. 798.

76 See Vandenbruwaene (W.), op. cit., p. 65-68.

77 Stelzer (M.), ‘Constitutional Change in Austria’, in Contiades (X.) (ed.), Engineering Constitutional Change, Routledge, London, 2013, p. 29.

78 For more detail, Popelier (P.), op. cit., n. 73. Therefore arguing for the introduction of shared powers in the case of further decentralization of social competences: Popelier (P.) and Cantillon (B.), ‘Bipolar federalism and the social welfare state: a case for shared competences’, Publius: the journal of federalism, vol. 43, n°4, 2013, pp. 626-647.

79 Poirier (J.), ‘Formal Mechanisms of Intergovernmental Relations in Belgium’, Regional & Federal Studies, vol. 12, n°3, 2002 ; Trench (A.), ‘Intergovernmental relations: in search of a theory’, in Greer (S.L.), Territory, Democracy and Justice, Palgrave MacMillan, New York, 2006, p. 231.

80 Palermo (F.), ‘Italy: A Federal Country without Federalism?’, in Burgess (M.) and Tarr (G.A.), op. cit., n. 55, p. 248 notes that ‘constitutional adjudication has shaped the contours of Italian regionalism much more than constitutional amendments have’.

81 Shapiro (M.), Courts: a comparative political analysis, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1981, p. 55.

82 Bzdera (A.), ‘Comparative Analysis of Federal High Courts: A Political Theory of Judicial Review’ Canadian Journal of Political Science, vol. 26, n°1, p. 19.

83 For an overview of courts world-wide, see Aroney (N.) and Kincaid (J.), Courts in Federal Countries. Federalists or Regionalists?, University of Toronto Press, Toronto, 2017.

84 Popelier (P.), ‘Federalism Disputes and the Behavior of Courts: Explaining Variation in Federal Courts’ Support for Centralization’, Publius: the Journal of Federalism, vol. 47, n°1, 2017, pp. 41-44.

85 Popelier (P.) and Bielen (S.), ‘How Courts Decide Federalism Disputes: Legal Merit, Attitudinal Effects, and Strategic Considerations in the Jurisprudence of the Belgian Constitutional Court’, Publius: the Journal of Federalism, vol. 49, n°4, 2019, pp. 7-10.

86 For more detail, see Popelier (P.), op. cit. n. 84 for a comparative study, and Popelier (P.) and Bielen (S.), op. cit., for Belgium in particular.

87 See the empirical studies on the effects of judicial preferences on case outcomes in European Constitutional Courts: Dalla Pellegrina (L.) and Garoupa (N.), ‘Choosing between the Government and the Regions: An Empirical Analysis of the Italian Constitutional Court Decisions, European Journal of Political Research, n° 52, 2013, pp. 558-580; Dalla Pellegrina (L.), De Mot (J.), Faure (M.) and Garoupa (N.), ‘Litigating Federalism: An Empirical Analysis of Decisions of the Belgian Constitutional Court’, European Constitutional Law Rev, vol. 13, n°2, 2017, pp. 305-346 ; Garoupa (N.), Gomez-Pomar (F.) and Grembi (V.), ‘Judging under Political Pressure: An Empirical Analysis of Constitutional Review Voting in the Spanish Constitutional Court’, Journal of Law, Economics and Organization, vol. 29, n°3, 2011, pp. 513-534 ; Magalhães (P.), The limits of judicialization: legislative politics and constitutional review in the Iberian Democracies, Ohio State University, Colombus, Ph.D. thesis, 2003, pp. 271-320.

88 Graziadei (S.), ‘Power Sharing Courts’, Contemporary Southeastern Europe, vol. 3, n°1, pp. 66-105.

89 The political majorities in the bench did seemed to play a role – more centralist with Christian-democrats, more decentralist with socialists – but as the bench varies in each case, these influences balance each other out in the long run.

90 Popelier (P.), op. cit., n. 84, p. 40.

91 Shapiro (N.), op. cit., p. 55.

92 Popelier (P.) and Bielen (S.), op. cit., pp. 64-65.

93 Poirier (J.), op. cit., p. 34.

94 Pas (W.), ‘A dynamic federalism built on static principles: The case of Belgium’, in Tarr (G.A.), Williams (R.F.) and Marko (J.) (eds.), Federalism, subnational constitutions, and minority rights, Praeger, New York, 2004, p. 160.

95 See Pal Singh (M.), ‘India’, in Oliver (d.) and Fusaro (C.) (eds.), How Constitutions Change. A Comparative Study, Hart, Oxford, 2011, p. 189 on how WTO obligations resulted in central legislation on agriculture, which is an exclusive competence of the States.

96 For an overview of this view in US doctrine and case law, see Halberstam (D.), ‘The Foreign Affairs of Federal Systems: A National Perspective on the Benefits of State Participation’, Villanova Law Review, n°46, pp. 1022-1027.

97 Critical for this reason: Halberstam (D.), ibid., p. 1056.

98 Art. 167 § 4 Belgian Constitution and Art. 9 of the Cooperation Agreement ‘Mixed Treaties’ of 8 March 1994.

99 Tierney (S.), ‘Giving with one hand: Scottish devolution within a unitary state’, International Journal of Constitutional Law, vol. 5, n°4, 2007. See also with regard to Spain: Maiz (R.), Caamaño (F.) and Azpitarte (M.), ‘The Hidden Counterpoint of Spanish Federalism: Recentralization and Resymmetrization in Spain (1978-2008)’, Regional & Federal Studies, vol. 20, n°1, 2010, p. 78.

100 Art. 7 Protocol No 2 on the Application of the Principles of Subsidiarity and Proportionality.

101 As imposed by Art. 4(2) TEU.

102 For more detail, see Popelier (P.), ‘Subnational multilevel constitutionalism’, Perspectives on Federalism, vol. 6, n°2, 2014, pp. 9-18.

103 Cooperation agreement of 8 March 1994. In practice, according to a gentleman’s agreement, the veto right is only used by actors with competences in the concrete matter, see Bursens (P.), ‘Het Europese beleid in de Belgische federatie’, Res Publica, vol. 1, n°1, p. 67.

104 Subsidiarity – Inter-Parliamentary Cooperation Agreement of 29 March 2017.