Lower Devonian lithostratigraphy of Belgium

Abstract

The revision of the lithostratigraphic scale of southern Belgium, based on the revised Geological Map of Wallonia and recent stratigraphic and sedimentological works lead to the re-definition of 75 lithostratigraphic units for the Lower Devonian Series. Most of the units described in the present paper are classical subdivisions of the lithostratigraphic scale but updates on their definition, boundaries and age are provided here. New terms are introduced for remarkable beds and facies. Groups are introduced to gather formations than are rarely separated on geological maps whereas some units previously described as formations are here retrograded to members. The dominant lithologies of the Lower Devonian of Belgium reflect siliciclastic sedimentation in various depositional settings ranging from fluviatile conglomerate to estuarine and deltaic sandstone, tidal siltstone and distal delta-front shale on the southern margin of the London–Brabant Massif and around other Caledonian inliers (e.g. Rocroi, Stavelot–Venn). The vertical succession and lateral correlation of the lithostratigraphic units allow to reconstruct the evolution of the shallow basin from the latest Silurian (Pridoli) to the latest Emsian.

1. Introduction

1Since the pioneer works of Dumont (1832, 1848), Dewalque (1868) and Gosselet (1885, 1888), the Devonian lithostratigraphic scale of Belgium was built up patiently through dating and correlations. The geological mapping program of the national territory in the late 1800s and early 1900s produced a stratigraphic framework characterised by its precision and the continuous updating of the legend of the Carte géologique de la Belgique à l’échelle du 40 000e from 1892 to 1929 (e.g. Conseil de Direction de la Carte, 1892; Conseil géologique, 1929). The fundamental monograph by Asselberghs (1946), which represents the culmination of his research on the Lower Devonian of southern Belgium, was the authoritative work for decades, before being adapted by Godefroid (1982) and Godefroid & Stainier (1982). The onset of the revision of the geological maps of Wallonia in the early 1990s, coupled to the works of the National Subcommission on Devonian Stratigraphy, led to the revision by Godefroid et al. (1994) of the Lower Devonian of the Vesdre area, the Theux Window and the Dinant Synclinorium. However, as the latter focused only on the northern part of the basin, the lithostratigraphical scheme of most of the Ardenne was not revised and, consequently, Asselberghs (1946) remained the only comprehensive reference. However, during the mapping of the Ardenne in the frame of the revised Geological Map of Wallonia, the mapping geologists had to introduce several new units to supplement Godefroid et al.’s (1994) lithostratigraphic framework and to update Asselberghs (1946). This has been done through the publication of the explanatory booklets of the geological maps, followed by their ratification by the National Commission for Stratigraphy in Belgium.

2Attention is drawn here on the fact that the Lower Devonian lithostratigraphic units are still facing a lot of uncertainties due to 1) the lack of good continuous sections exposing vertical and lateral transition between formations, 2) the monotony of some facies, 3) the thickness of some units, reaching often several hundreds of metres, and 4) the lack of biostratigraphic markers allowing precise correlations between units.

3The present paper aims at updating and supplementing the Lower Devonian lithostratigraphic scale previously published by Godefroid et al. (1994) and summarised by Bultynck & Dejonghe (2002). This update is the result of a review of the tremendous work carried out by the geological cartographers and stratigraphers who have worked on the considered stratigraphic interval.

2. Geological setting

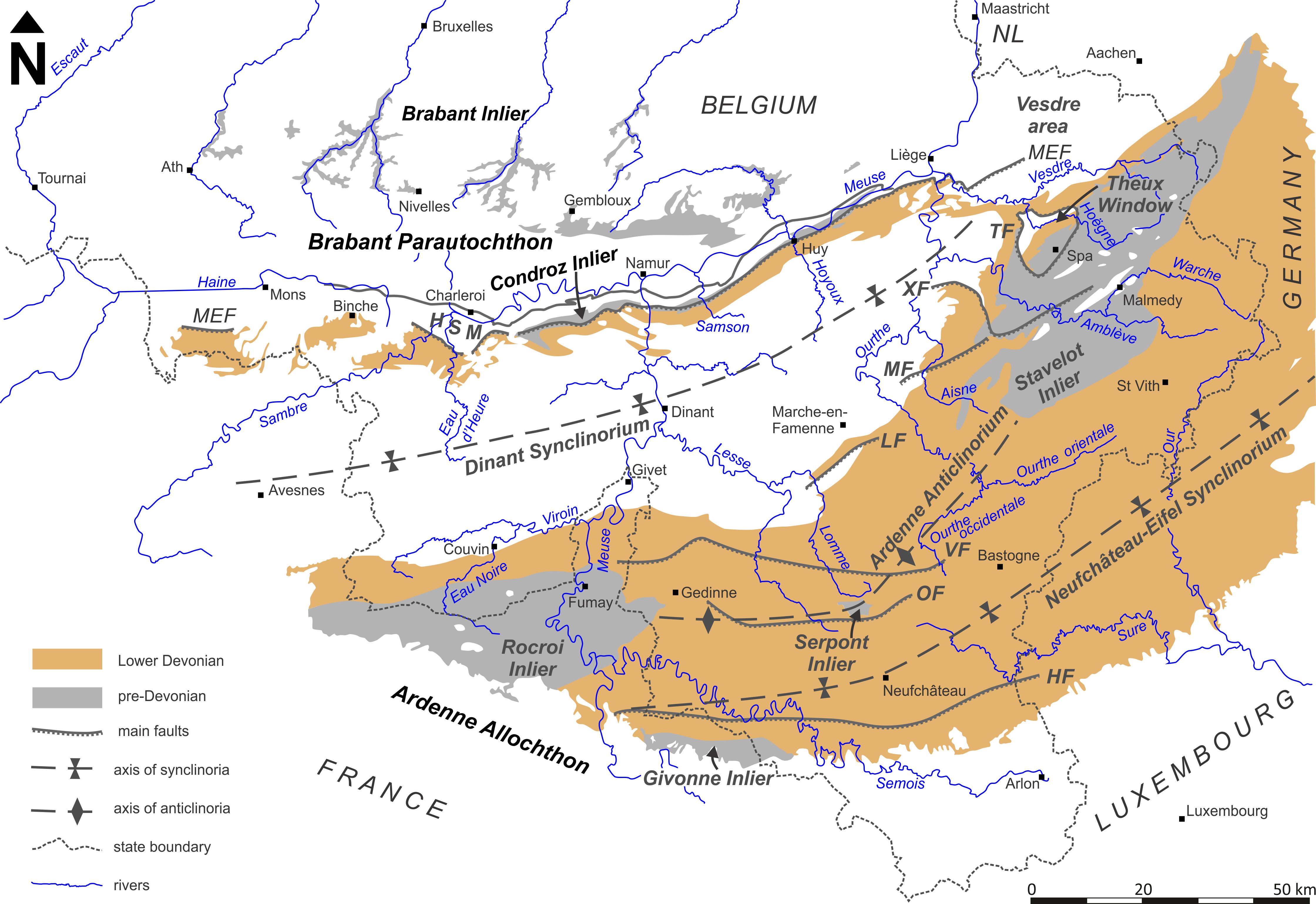

4The Lower Devonian covers large parts of southern Belgium and surrounding areas (Rhenish Massif, Eisleck in northern Luxembourg, French Ardennes) where it generally corresponds to densely forested high lands. In the Ardenne Allochthon, which corresponds to a Cambrian–Ordovician basement unconformably overlain by a thick Devonian and Carboniferous succession (Hance et al., 1999), these Lower Devonian formations crop out along the northern, south-eastern and southern limbs of the Dinant Synclinorium, as well as in the Ardenne Anticlinorium and the Neufchâteau–Eifel Synclinorium (Fig. 1). Lateral changes of facies in the lithostratigraphic units occur between the main structural units and are traditionally associated to major faults such as the Xhoris Fault and Midi–Eifel Thrust Fault (Fig. 1). However, as observed by Asselberghs (1946) and confirmed by recent geological mapping, the facies changes are more progressive and ‘transitional zones’ between facies are frequent. Such a transitional zone occurs along a c. 5 km wide corridor south of the Xhoris Fault. There, the Lower Devonian formations progressively change from the facies known along the southern limb of the Dinant Synclinorium to those known along its northern flank. However, the points where each formation passes to the other vary and can even be repeated. According to Marion & Barchy (in press, a, b), the change from the Mirwart Formation to the Bois d’Ausse Formation is observed c. 1 km south of the Mormont Fault, then, north of this fault, the Mirwart Formation is again recognisable then passes again to the Bois d’Ausse Formation. From there up to the Xhoris Fault, the characteristics of both formations are observed. Hence, to simplify, the Xhoris Fault is here cited as marking the change from one formation to the other.

5Some Lower Devonian formations also crop out in the Theux Window (and Bolland drillhole) and in a series of small outliers resting on the Haine–Sambre–Meuse Overturned Thrust sheets (Belanger et al., 2012) (Fig. 1). No Lower Devonian rock is known neither in the Brabant Parautochthon nor in the Campine Basin.

Figure 1. Simplified geological map of the Lower Devonian of southern Belgium and neighbouring countries, with indication of the main structural units, including the Caledonian inliers (adapted from de Béthune, 1954). Abbreviation: HSM, Haine–Sambre–Meuse Overturned Thrust sheets. Major fault abbreviations: HF, Herbeumont Fault; LF, Lamsoul Fault; MF, Mormont Fault; MEF, Midi–Eifel Thrust Fault; OF, Opont Fault; VF, Vencimont Fault; TF, Theux Fault; XF, Xhoris Fault.

3. Chronostratigraphy of the Lower Devonian

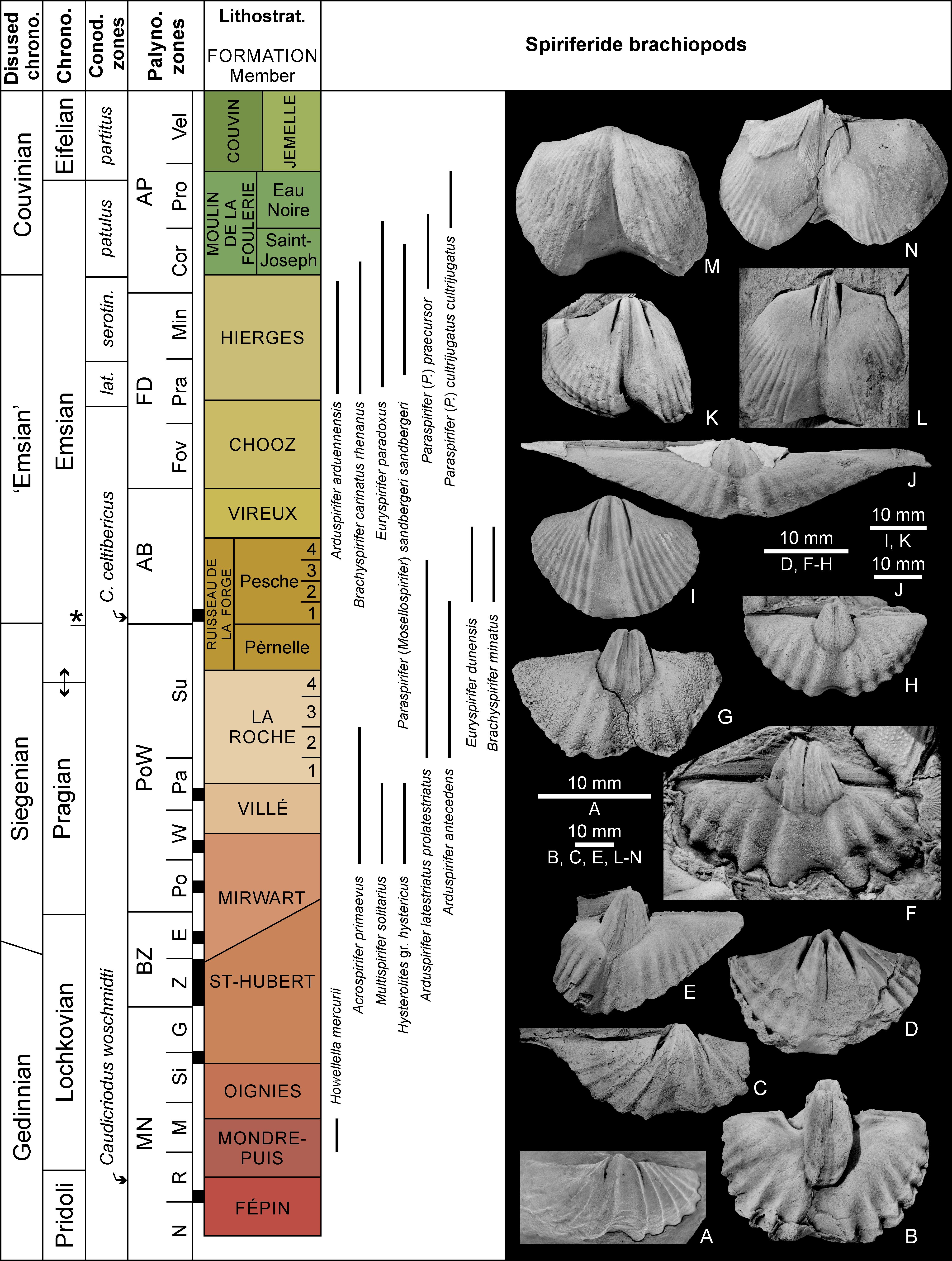

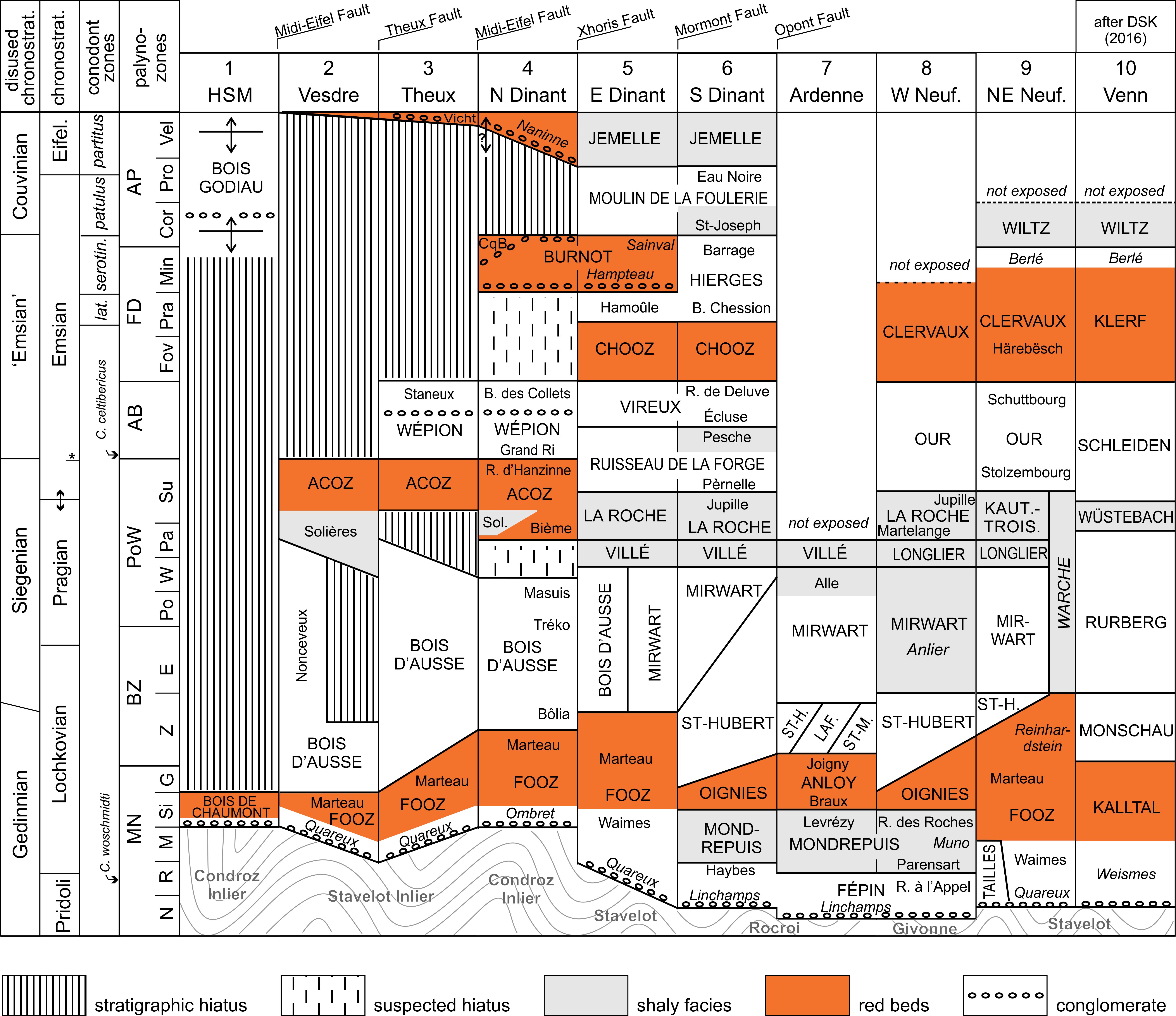

6Traditionally, the thick Lower Devonian sequence was divided into Gedinnian, Siegenian and Emsian stages in Belgium and surrounding areas. Theses subdivisions were mostly based on the lithology (shaly versus sandy) and the macrofaunal assemblages, notably those based on brachiopods (Bultynck, 1972). In this respect, the reader is referred to Godefroid et al. (1994, figs 4–6) for the history of the Lower Devonian subdivisions in the Dinant Synclinorium and the Vesdre area. Following the decision of the Subcommission on Devonian Stratigraphy (Bassett, 1985), the Gedinnian and Siegenian, which have poorly defined biostratigraphic limits, were abandoned and replaced by the Lochkovian and Pragian stages, whereas the Emsian got a new definition (Fig. 2). The formal definition of these stages is based on the first appearance data of planktic graptolite and conodont taxa. However, planktic graptolites are unknown from the Pridoli–Lower Devonian of Belgium and conodonts are mostly absent from this interval; therefore, it is impossible to precisely recognise the international divisions. The palynostratigraphic succession established by Steemans (1989a) in the Ardenne can be correlated with the Armorican Massif where spores occur together with chitinozoans. Fortunately, the chitinozoan biozones are also known in the Bohemian Massif where the Lochkovian and Pragian stages are defined. The cross-correlation spores/chitinozoans/conodonts allows to localise roughly the boundaries within the Belgian Lower Devonian succession.

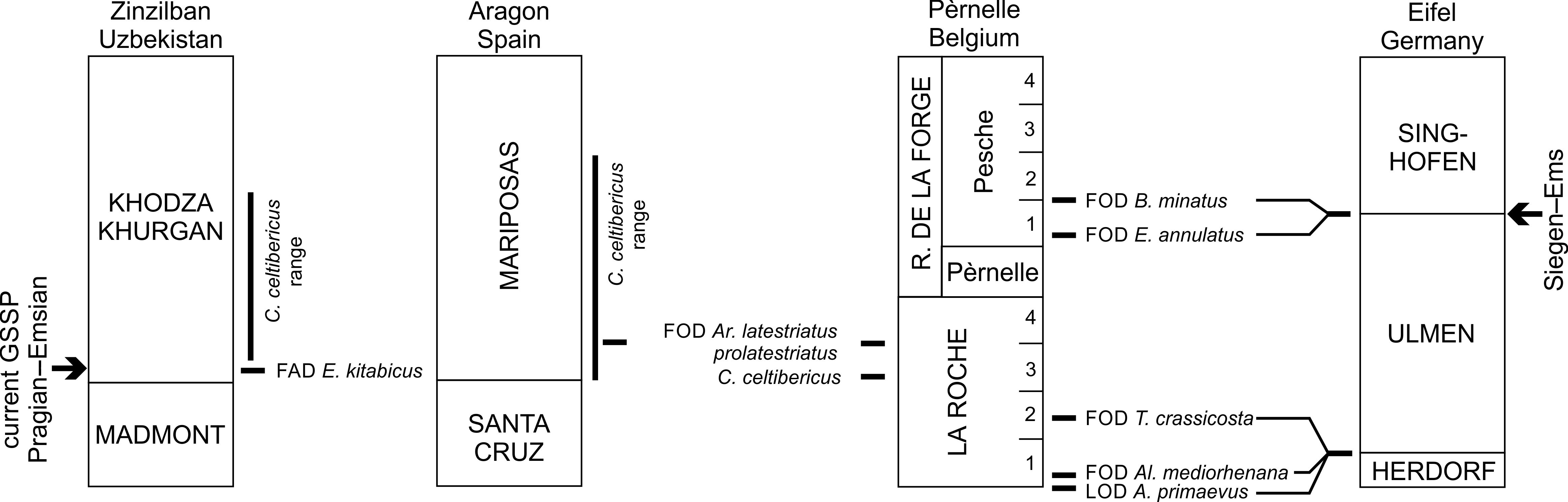

Figure 2. Correlation of the Pragian–Emsian boundary and Siegen–Ems boundary in Uzbekistan (GSSP), Spain, Belgium and Germany. Conodont and brachiopod data after Godefroid (1982), Carls & Valenzuela-Ríos (1993), and Bultynck et al. (2000). Abbreviations: A., Acrospirifer; Al., Alatiformia; Ar., Arduspirifer; B., Brachyspirifer; C., Caudicriodus; E., Eocostapolygnathus; FOD, first occurrence datum; R., Ruisseau; T., Torosospirifer.

7The base of the Lochkovian is defined by the first appearance datum (FAD) of the graptolite Monograptus uniformis uniformis, very close to the FAD of the conodont Caudicriodus woschmidti woschmidti (Martinsson, 1977). Both taxa being absent in the Ardenne, the correlation is made through the spores found in the Fépin Formation that indicate the N zone of the MN Oppel zone (Steemans, 1989a). The latter is close to the Silurian–Devonian boundary. Caudicriodus woschmidti woschmidti recovered from the Naux Limestone in the French Semoy River valley (Borremans & Bultynck, 1986) also suggests that the base of the Devonian sequence in the Ardenne is situated in an undifferentiated late Pridoli–early Lochkovian interval (Fig. 3). On the south-eastern flank of the Givonne Inlier (Fig. 1), the Mondrepuis Formation yielded a diverse brachiopod fauna including the athyridide Dayia shirleyi that is a typical Pridoli taxon (Godefroid, 1995; Godefroid & Cravatte, 1999). Therefore, the base of the former Gedinnian stage (Dejonghe et al., 2006) and the base of the Devonian sequence in the Ardenne is most probably still in the Silurian System as suggested by Bultynck (1977) and Borremans & Bultynck (1986) (see discussion in Godefroid & Cravatte, 1999).

8The base of the Pragian is defined by the FAD of the conodont Eognathus sulcatus but, as recent taxonomic revisions showed that typical forms are known below the Global Boundary Stratotype Sections and Point (GSSP) level in the type locality (Slavík & Hladil, 2004), this marker cannot be used anymore to define the base of the stage (Becker et al., 2020). According to Steemans (1989a), the base of the Pragian cannot be properly defined by spores as the current boundary falls within the E interval Zone. This zone is recognised in the uppermost part of the Saint-Hubert Formation in the Pèrnelle pond section, south of Couvin, and within the lower part of the Mirwart Formation in the Arville section, west of Saint-Hubert (Godefroid et al., 1994). In proximal areas, the spores demonstrate the diachronism of the lithological units historically used for the definition of the Gedinnian–Siegenian boundary (Steemans, 1989a; Hance et al., 1992).

9The current GSSP for the base of the Emsian is defined by the FAD of the conodont Polygnathus kitabicus (Eocostapolygnathus kitabicus sensu Bardashev et al., 2002). However, this boundary falls much lower than the base of the Emsian in the classical regions of Germany (Jansen, 2016, 2019) and Bohemia (Slavík et al., 2007). Hence, the base of the Emsian is currently under revision by the Subcommission on Devonian Stratigraphy. The GSSP-defined Pragian–Emsian boundary is not recognised in Belgium as the conodont markers are lacking (Bultynck et al., 2000). The brachiopod Arduspirifer latestriatus prolatestriatus (Fig. 3F), which is known from the upper part of the La Roche Formation, also occurs in Spain in beds yielding the conodont Caudicriodus celtibericus, a secondary marker of the base of the Emsian (Carls, 1987; Jansen, 2016). Therefore, following this cross-correlation, the Pragian–Emsian boundary lies in the upper part of the La Roche Formation (Figs 2, 3).

10In Germany, however, the ‘traditional’ base of the Emsian (i.e. ‘Siegen-Ems’ boundary sensu Solle, 1950) is based on the appearance of the brachiopod Brachyspirifer minatus (Fig. 3I) (Jansen, 2016) that is coincident with the boundary between the Ulmen and Singhofen groups (Fig. 2). At the same level Riegel & Karathanasopoulos (1982) documented the first occurrence of the miospore Emphalisporites annulatus. Brachyspirifer minatus occurs in the lower part of the Pesche Member in the Pèrnelle pond section (Godefroid & Stainier, 1982), together with E. annulatus (Steemans et al., 2002). The traditional Siegenian–Emsian boundary should consequently be localised near the base of the Pesche Member. It must be noted that the German stratigraphers tend to come back to the historical Siegenian–Emsian boundary in the Rhenish Massif for pragmatic reasons (Jansen, 2016). In parallel, the Subcommission on Devonian Stratigraphy is currently examining the possibility to re-define the base of the Emsian with the FAD of the conodont Eolinguipolygnathus excavatus morphotype 114 that is relatively close to the historical Siegenian–Emsian boundary (Carls et al., 2008; Becker et al., 2020).

Figure 3. Biostratigraphic zonations (conodonts, miospores) of the Lower Devonian succession on the southern and south-eastern limbs of the Dinant Synclinorium (southern Belgium) and range of selected spiriferides (compilation from Godefroid & Stainier, 1982; Steemans, 1989a; Godefroid et al., 1994; Bultynck et al., 2000; Godefroid, 2001). The asterisk indicates the possible revised base of the Emsian Stage, under discussion among the Subcommission on Devonian Stratigraphy of the International Commission on Stratigraphy (see Becker et al., 2020). Conodont zones: lat., laticostatus; serotin., serotinus. Other abbreviations: chrono., chronostratigraphy; lithostrat., lithostratigraphy; palyno, palynological. Black boxes represent the palynomorph-yielding samples (see Steemans, 1989a) and insight on the precision of the correlations. Numbers 1 to 4 in La Roche Formation and Pesche Member are the lithological units described by Godefroid (1979). A–N. Spiriferide brachiopods from the Lower Devonian of Belgium. All specimens were coated with ammonium chloride (except otherwise stated) and are part of the palaeontological collections of the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences (prefixed RBINS). A. Howellella mercurii, internal mould of a ventral valve (RBINS a556; neotype); Mondrepuis (France), Mondrepuis Formation (SEM; from Mottequin, 2019). B. Acrospirifer primaevus, ventral view of a flattened articulated internal mould (RBINS a14017); La Roche-en-Ardenne, Villé Formation. C. Multispirifer solitarius, incomplete internal mould of a ventral valve (RBINS a1946); Dochamps, Villé Formation. D. Hysterolites gr. hystericus, ventral view of an articulated internal mould (RBINS a1991); Harzé, Solières Member. E. Euryspirifer dunensis, incomplete internal mould of a ventral valve (RBINS a7903); Grupont, Pesche Member. F. Arduspirifer latestriatus prolatestriatus, internal mould of a ventral valve (RBINS a7913b); Grupont, Pesche Member. G. Arduspirifer antecedens, internal mould of a ventral valve (RBINS a2912); Couvin, La Roche Formation. H. Arduspirifer arduennensis arduennensis, internal mould of a ventral valve (RBINS a1317); Rochefort, Hierges Formation. I. Brachyspirifer minatus, internal mould of a ventral valve (RBINS a2150; holotype); Pèrnelle pond, Pesche Member. J. Euryspirifer paradoxus, internal mould of a ventral valve with shelly remains (RBINS a7882); Couvin, Hierges Formation. K. Brachyspirifer carinatus rhenanus, incomplete internal mould of a ventral valve (RBINS a2196); Couvin, Hierges Formation. L. Paraspirifer (Mosellospirifer) sandbergeri sandbergeri, internal mould of a ventral valve (RBINS a1357); Couvin, Hierges Formation. M. Paraspirifer (Paraspirifer) praecursor, ventral valve (RBINS a1358); Nismes, Saint-Joseph Member. N. Paraspirifer (Paraspirifer) cultrijugatus cultrijugatus, internal mould of a ventral valve with shelly remains (RBINS a1324); Couvin, Eau Noire Member.

4. Geochronology of the Early Devonian

11The Early Devonian extends from c. 419.0 Ma to c. 394.3 Ma and is subdivided into three ages: Lochkovian (c. 419.2 Ma to c. 412.4 Ma), Pragian (c. 412.4 Ma to c. 410.5 Ma), and Emsian (c. 410.5 Ma to c. 394.3 Ma) (Becker et al., 2020).

5. Biostratigraphy of the Lower Devonian

12As exposed earlier, the conodont biostratigraphy has a poor resolution in the Lower Devonian of Belgium, carbonate facies being very rare (Bultynck et al., 2000). A biostratigraphy based on spiriferide brachiopods has been applied in the marine facies but again, the distribution of the taxa along the sedimentary sequence is very scarce and discontinuous, and it does not allow accurate divisions (Godefroid et al., 1982; Godefroid, 1994a, 2001; Godefroid et al., 2002). Moreover, a revision of the representatives of some genera (e.g. Arduspirifer) is needed (Mottequin & Jansen, in press). The most stratigraphically significant taxa are given in Figure 3.

13The palynostratigraphic scale, which was developed by Steemans (1989a) and Steemans et al. (2002), yielded rather good results in more proximal settings and allows long-distance correlations with the Rhenish, Bohemian and Armorican massifs. However, it has to be noted that the palynological record is scarce as well. As pointed out by Steemans (1989a), a very small fraction of the Lower Devonian lithological succession, over 8 km thick, yielded miospore assemblages. The biostratigraphic correlations presented here (Fig. 3) should therefore be used considering this relative precision.

6. Evolution of the Namur–Dinant Basin during the Early Devonian

14The Namur–Dinant Basin belongs to the passive margin of the Laurussian continent during the Early Devonian. Its Cambrian–Silurian basement is visible in the Caledonian massifs (also called inliers) of Belgium, namely the London–Brabant Massif, north of the basin, and the Rocroi, Givonne, Serpont, and Stavelot–Venn inliers in its southern part, whereas the Ordovician–Silurian Condroz Inlier occupies an intermediate position (Figs 1, 4, see also Mottequin & Denayer, 2024). From the Pridoli (latest Silurian) onwards, coarse, immature siliciclastic sediments resulting from the erosion of these massifs accumulated over a large area. The conglomerate marking the base of the transgression consists of superposed debris-flows in an alluvial-lagoonal setting (Meilliez, 1984). It fills palaeo-depressions where the basement was not entirely peneplaned (Michot, 1969). The sediment sources are variable and the transportation seemingly limited judging by the similarity of the elements of the conglomerate and the rocks of the aforementioned massifs (Neumann-Mahlkau, 1970). Sediments directly overlying the conglomerate yield Pridoli marine fauna in the Ardenne (Muno, Waimes), whereas north of the Rocroi and Stavelot–Venn inliers the facies are more proximal, and the microflora suggest a Lochkovian age (Steemans, 1982a, b). Based on these diachronous ages, Steemans (1989b) and Godefroid & Cravatte (1999) reconstructed the transgression northwardly onto the basement from the south-east, south-west, and south.

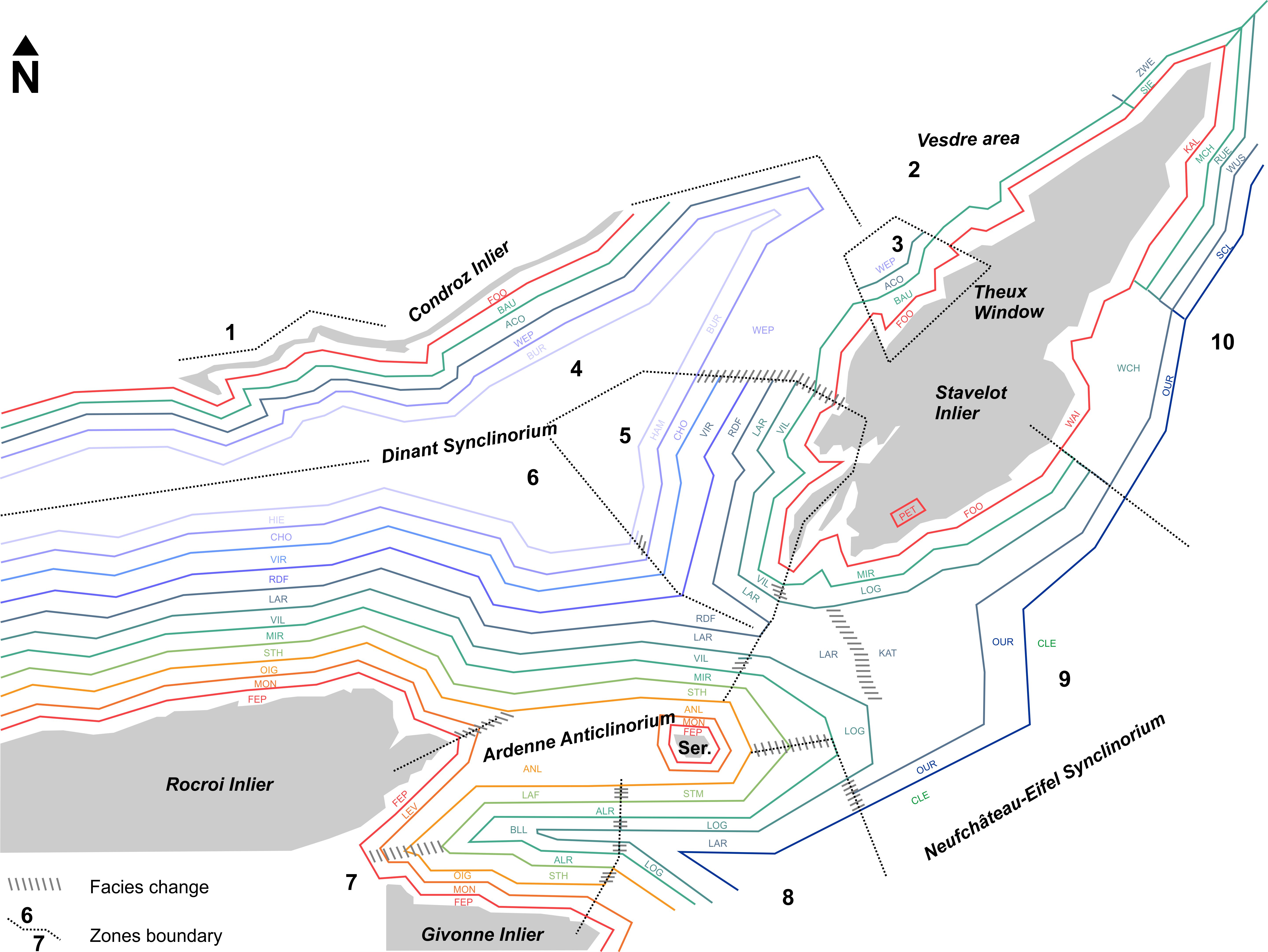

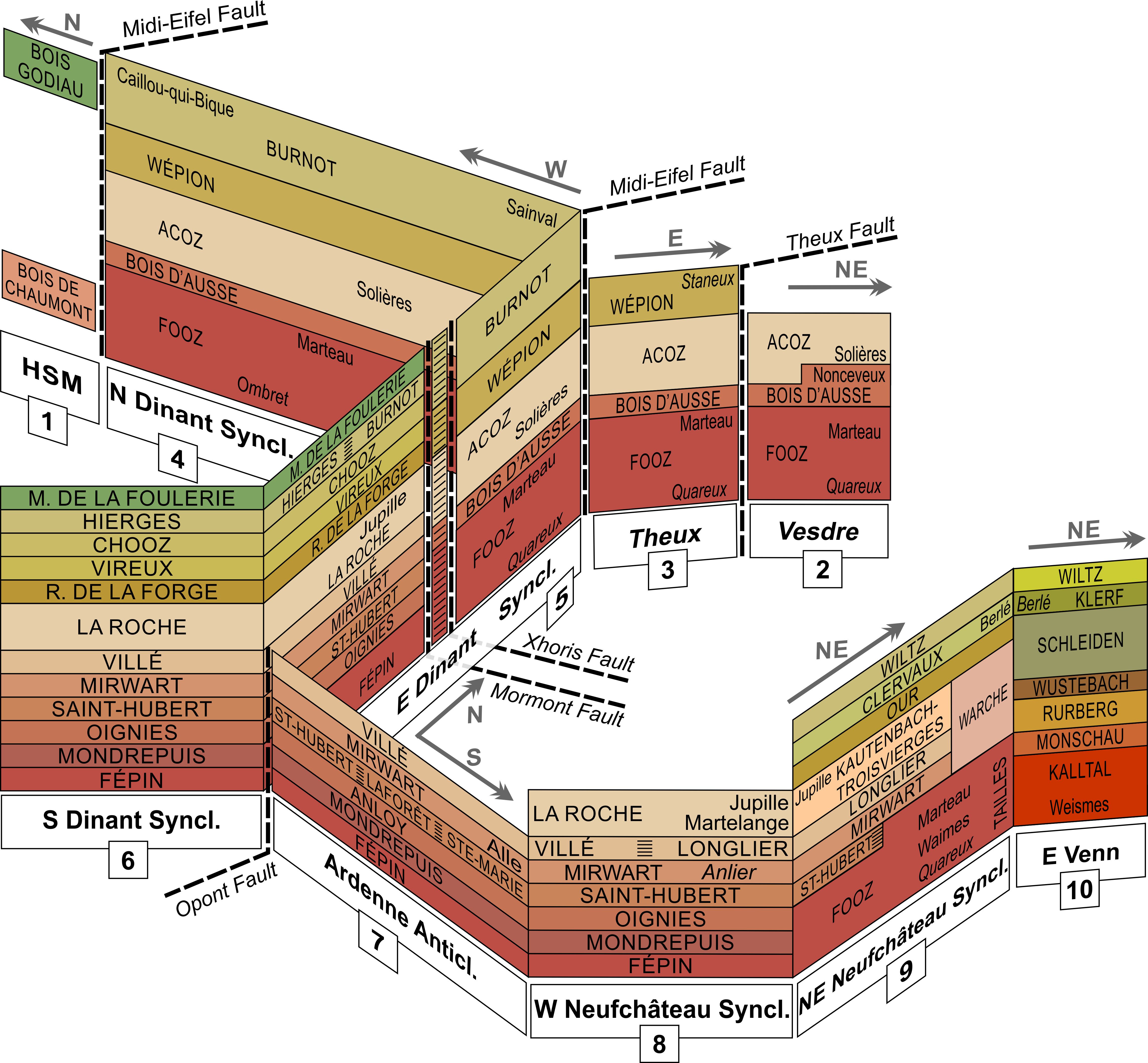

Figure 4. Simplified map (not to scale) showing the distribution of the Caledonian inliers, south of the Brabant Massif, and the main sedimentation areas of the Lower Devonian of southern Belgium and neighbouring countries (modified after Asselberghs, 1946 and updated). 1, Haine–Sambre–Meuse Overturned Thrust sheets; 2, Vesdre area; 3, Theux Window; 4, Northern limb of the Dinant Synclinorium; 5, Eastern limb of the Dinant Synclinorium; 6, Southern limb of the Dinant Synclinorium; 7, Ardenne Anticlinorium; 8, Western part of the Neufchâteau–Eifel Synclinorium; 9, North-eastern part of the Neufchâteau–Eifel Synclinorium; 10, German Venn area. See Fig. 5 for details on the lithostratigraphic succession. Abbreviations of the lithostratigraphic units: ACO, Acoz Formation; ALR, Anlier Facies (Mirwart Formation); ANL, Anloy Formation; BAU, Bois d’Ausse Formation; BLL, Bouillon Facies (Villé Formation); BUR, Burnot Formation; CHO, Chooz Formation; CLE, Clervaux Formation; FEP, Fépin Formation; FOO, Fooz Formation; HAM, Hampteau Facies (Burnot Formation); HIE, Hierges Formation; KAL, Kaltall-Formation; KAT, Kautenbach–Troisvierges Formation; LAF, Laforêt Formation; LAR, La Roche Formation; LEV, Levrézy Member (Mondrepuis Formation); LOG, Longlier Formation; MCH, Monschau-Formation; MIR, Mirwart Formation; MON, Mondrepuis Formation; MUN, Muno Facies; OIG, Oignies Formation; OUU, Our Formation; RDF, Ruisseau de la Forge Formation; RUE, Rurberg-Formation; SCL, Schleiden-Formation; SER, Serpont Inlier; SIE, Siegen-Formation; STH, Saint-Hubert Formation; STM, Sainte-Marie Formation; PET, Petites Tailles Formation; VIL, Villé Formation; VIR, Vireux Formation; WCH, Warche Group; WAI, Waimes Member (Fooz Formation); WEP, Wépion Formation; WIL, Wiltz Formation; WUS, Wüstebach-Formation; ZWE, Zweifal-Formation.

15By the end of the Lochkovian, finer-grained sediments deposited on coastal setting in the northern part of the basin. The more open-marine environments observed in the Ardenne Anticlinorium and Neufchâteau Synclinorium progressed northwards during the Pragian and reached the northern edge of the Stavelot–Venn Inlier and the Condroz Inlier (Fig. 4). The increasing marine nature of the facies, with occasional carbonate, reflects a northwards-southwards deepening (Blieck et al., 1988; Godefroid et al., 1994). In the southern part of the basin, rapid increases in thickness of the deposit suggest the structuration into several sedimentation areas with distinct subsidence rate. The interplay of ENE-WSW-oriented faults defines compartments of a half-graben deepening southwards, in a general extensive tectonic context (Meilliez et al., 1991).

16The Emsian records the return of coarse-grained siliciclastic sediments in the northern part of the basin (Fig. 5). The reddish-coloured conglomerates show a resumption of erosion on the continent during a particular lowering of the sea level. In the southern part of the basin and eastwards, towards Luxembourg and Germany, considerably thick shallow-water siliciclastics accumulated (Dejonghe et al., 2017). In the southern area, sedimentation under marine influence continued during the Emsian through the rest of the Devonian but in the northern area, the conglomeratic Burnot Formation marks the end of the Lower Devonian sedimentation (Fig. 5), with probable depositional hiatus and erosional event.

17Pridoli–Lower Devonian succession, considered as the post-Caledonian molasse, reaches a total thickness of 1500 m and nearly 5000 m in the northern and southern parts of the basin (Asselberghs, 1946), respectively.

Figure 5. Chronostratigraphic chart of the Lower Devonian strata of Belgium and its correlation with the charts of Germany and central Europe (origin of data: see main text). Formations are indicated in capital letters, members in regular letters whereas remarkable beds and facies are indicated in italics. The asterisk indicates the possible revised base of the Emsian Stage, currently under discussion among the Subcommission on Devonian Stratigraphy of the International Commission on Stratigraphy (see Becker et al., 2020). Conodont biozonation after Slavík (2004) and Carls et al. (2007); palynozones after Streel et al. (1987); German succession (no. 10) after Deutsche Stratigraphische Kommission (DSK, 2016). Abbreviations: B. Chession, Bois Chession Member; B. des Collets, Bois des Collets Member; CqB, Caillou-qui-Bique Member; disused chrono., disused chronostratigraphy; HSM, Haine–Sambre–Meuse Overturned Thrust sheets; KAUT.-TROIS., Kautenbach–Troisvierges Formation; LAF., Laforêt Formation; Neuf., Neufchâteau–Eifel Synclinorium; R. à l’Appel, Roche à l’Appel Member; R. d’Hanzinne, Ruisseau d’Hanzinne; R. de Deluve, Ruisseau de Deluve; R. des Roches, Ruisseau des Roches Member; Sol., Solières Member; ST-M., Sainte-Marie Formation; ST-H., Saint-Hubert Formation; TAILLES, Petites Tailles Formation.

7. Lower Devonian lithostratigraphic units

7.1. Preliminary remarks

18All the lithostratigraphic units (Fig. 6) are listed alphabetically as a lexicon, notwithstanding their age and geographic distribution. The reader is referred to the Figures 1–6 for further information concerning the latter data.

19We have indicated the oldest references, which may explain certain discrepancies between the present work and previous ones (Godefroid et al., 1994; Bultynck & Dejonghe, 2002), as is the case for the Fépin Formation. A history of the subdivisions of the Lower Devonian of the Dinant Synclinorium and the Vesdre area was provided by Godefroid et al. (1994) and complements those published by Asselberghs (1946), Godefroid (1982), and Godefroid & Stainier (1982) that also dealt with the units present outside the aforementioned areas.

20Most of the descriptions provided in this chapter are synthetised from previous publications such as the abovementioned lithostratigraphic charts, complemented by more recently published data, notably from the revised Geological Map of Wallonia (Carte géologique de Wallonie). To be coherent with the latter, new names are proposed here for units that were previously grouped for mapping purposes. The Pèrnelle and Pesche formations are thus demoted here as members of the newly introduced Ruisseau de la Forge Formation as is the case of the Saint-Joseph and Eau Noire formations that are considered here as members of the newly introduced Moulin de la Foulerie Formation, whereas the Warche Group is introduced in this paper to designate the informal grouping of the Mirwart, Villé and La Roche formations (see details below). However, as some informal groupings used on several sheets of the Geological Map of Wallonia are the result of the lack of outcrops (e.g. Regroupement Mirwart-Villé in Marion & Barchy, 1999, or Regroupement Acoz-Wépion-Burnot in Mottequin et al., 2021) rather than natural stratigraphic groups, they have not been formalised.

21Units undistinguishable in the field or bearing distinct names in separate areas are also synonymised (e.g. Marteau and Fooz formations, Burnot and Hampteau formations, etc.) after thoughtful discussion and argumentation. Informal members (e.g. Arkose d’Haybes, Arkose de Waismes, etc.), remarkable beds (e.g. Poudingue de Quareux, Quartzite de Berlé, etc.) and facies (e.g. Paliseul Facies, Anlier Facies, etc.) are also introduced with formal definitions. As far as possible, existing names were retained unless they were confusing or already in use for other units. For example, the Arkose de Dave has not been transformed into a Dave Member as an eponymous formation is already used in the lower Paleozoic lithostratigraphic chart.

Figure 6. Schematic vertical and lateral relationships of the Lower Devonian units of Belgium. Formations are indicated in capital letters, members in regular letters whereas remarkable beds and facies are indicated in italics. Abbreviations: Anticl., Anticlinorium; HSM, Haine–Sambre–Meuse Overturned Thrust sheets; M. DE LA FOULERIE, Moulin de la Foulerie Formation; R. DE LA FORGE, Ruisseau de la Forge Formation; Syncl., Synclinorium. Numbers 1 to 10 refer to the sedimentation zones defined in Fig. 4. German succession (column 10) after Deutsche Stratigraphische Kommission (2016).

7.2. Descriptions

Acoz Formation – ACO

22Origin of name. Section on the eastern flank of the Bième valley (also named Ruisseau d’Hanzinne), between Acoz and Bouffioulx, Cb2 Schistes rouges et grès roses d’Acoz in Conseil de Direction de la Carte (1892, p. 228). The same year, de Dorlodot (1892, p. 306) introduced the schistes siliceux et grès d’Acoz.

23Description. The Acoz Formation is dominated by reddish-coloured siliciclastics. Its base is defined by the first occurrence of reddish siltstone and argillaceous sandstone beds overlying the light-coloured quartzite of the Bois d’Ausse Formation. In its type area, the Acoz Formation is divided into two members, from base to top: the Bième Member – BME (Membre de la Bième, Dejonghe et al., 1994a, p. 121) dominated by dark reddish siltstone and shale, and the Ruisseau d’Hanzinne Member – RHZ (Membre du Ruisseau d’Hanzinne, Dejonghe et al., 1994a, p. 121) enriched upwards in reddish sandstone and metric to plurimetric beds of light-coloured quartzite, and associated with greenish, pinkish or yellowish siltstone and shale (Fig 7A). Quartzite beds contain red shaly pebbles.

24Laterally, a shaly unit appears eastwards and was named the Solières Formation (Hance et al., 1992; Dejonghe et al., 1994b). It was mapped as such in the Vesdre area (Laloux et al., 1996) and on the eastern margin of the Dinant Synclinorium by Marion et al. (in press) but, as its development is very limited, it was considered as a member of the Acoz Formation by Delcambre & Pingot (2018). The Solières Member – SOL (schistes et grès noirs de Solières in Maillieux & Demanet, 1929, p. 126) is dominated by greyish to bluish shale and siltstone with rare sandstone and quartzitic sandstone interbeds (Fig. 7B). The reddish colour, though occasional, is not as common as in the other members. Moreover, marine faunas (e.g. brachiopods, bivalves) are locally present (Maillieux, 1931; Mottequin & Jansen, in press). In the type area, the Solières Member is not intercalated between the Bois d’Ausse and Acoz formations as previously suggested by Hance et al. (1992) but entirely bracketed by the red siliciclastics of the Acoz Formation (Delcambre, 2023). The upper boundary is defined below the first sandstone and quartzitic sandstone of the Wépion Formation.

25Stratotype and sections. The Acoz Formation, and the Bième and Ruisseau d’Hanzinne members are exposed on the eastern side of the Hanzinne River (also named Bième River), between the disused quarries of the Bois de Châtelet and the Bois d’Acoz. The Solières Member was defined in a small quarry situated north of the eponymous village (Fourmarier, 1912) but a parastratotype was proposed by Monseur (1959) on the right bank of the Amblève River valley, north of Nonceveux.

26Area and lateral variations. The Formation is present along the northern and north-eastern limbs of the Dinant Synclinorium and in the Vesdre area but, in the latter region, the Bième and Ruisseau d’Hanzinne members are not recognised, as light-coloured quartzite beds already occur in the lower part of the Formation. The Solières Member is known east of the Samson River valley, and only individualised from place to place on the northern flank of the Dinant Synclinorium. The Acoz Formation is also recorded in the Bolland borehole (Graulich, 1975).

27Thickness. The Formation is 300 m thick west of the Meuse River valley (140 m and 160 m for the Bième and Ruisseau d’Hanzinne members, respectively) and up to 400 m thick east of this valley (Delcambre & Pingot, 2000a, 2017). In the Vesdre area, the thickness depends on the reworking induced by the overlying Eifelian conglomerate (Vicht Formation, see Denayer et al., 2024) and varies from 250 m in Eupen, 50 m in Pepinster and 0 m in Heusy (Dejonghe et al., 1994a). The Solières Member is 125 m thick in the Amblève River valley, 130 m in the Hoyoux River valley (where it was merged with the Bois d’Ausse Formation by Mottequin et al., 2021) and less than 50 m at Solières (Dejonghe et al., 1994b; Delcambre, 2023).

28Age. Pragian. Steemans (1989a) attributed the Acoz Formation to the Pa to Su zones in the Dinant Synclinorium and to the E to Su zones in the Vesdre area, suggesting a younger age eastwards.

29Use. The quartzitic sandstones were locally used for building purposes.

30Main contributions. Asselberghs (1946), Monseur (1959), Steemans (1989a), Hance et al. (1992), Dejonghe et al. (1994a, 1994b).

Figure 7. Illustration of some Lochkovian units. A. Reddish silty sandstone with yellowish stains (dolomitic material) of the Acoz Formation. Hand sample from the Hoyoux River valley (width of the picture c. 5 cm). B. Black shale and siltstone of the Solières Member of the Acoz Formation. Section along the Amblève River at Nonceveux. C. Transition from the green shale of the Saint-Hubert Formation to the purple siltstone of the Anloy Formation. Section along the railway south of Poix-Saint-Hubert station.

Alle Member – ALL

31See Mirwart Formation.

Anlier Facies

32See Mirwart Formation.

Anloy Formation – ANL

33Origin of name. After the village of Anloy, Schistes bigarrés d’Anloy in Gosselet (1888, p. 233).

34Description. This unit consists of light blue-grey quartzite and siltstone in decimetre-thick regular beds with shaly laminae. Carbonate nodules, which appear decalcified and limonitic on the outcrop, occur together with decarbonated sandstone and micaceous sandstone beds. The coarser-grained lithologies form lenticular beds that display planar, oblique and cross laminations or are bioturbated. Rare desiccation cracks and bone beds occur in the upper part of the Formation whereas plurimetric bundles of lenticular, coarse-grained arkosic sandstone beds are locally developed in its lower part (Fig. 7C).

35In the Semois valley, the Anloy Formation can be divided into two members. The lower one, the dominantly sandy Braux Member – BRO (quarzophyllades [sic] de Braux and Quarzophyllades [sic] oligistifères de Braux in Gosselet, 1880, p. 62 and p. 67, respectively), starts with 50–100 cm thick beds of argillaceous to quartzitic (or carbonate), fine-grained sandstone overlying the slate of the Mondrepuis Formation. Some shaly and silty intercalations occur. The dominant colour is grey at the base, becoming greenish grey to reddish in the upper part of the Member. The upper Member, the Joigny Member – JOI (Schistes luisants panachés de Joigny (in Gosselet, 1880, p. 69) that were formally separated from the Schistes bigarrés d’Oignies by Gosselet (1888, p. 225) as the Schistes bigarrés de Joigny), is essentially slaty. The transition between both members is progressive as the thickness and the frequency of the sandy facies decrease. Homogeneous shale and siltstone with a silky touch and variegated colours dominate (Fig. 8A). Lenses and beds of argillaceous, occasionally carbonate and micaceous sandstone are intercalated in the shale. They pass to dark grey shales with silty laminae, then to dark blueish slates with lighter-coloured lenses. Several horizons display decalcified nodules, commonly filled with limonitic material. Greenish shaly horizons with small argillaceous flat pebbles and plant debris occur occasionally. The greenish-grey and blueish-grey dominant colour changes to reddish and variegated near the boundary with the overlying Sainte-Marie Formation. A metamorphic facies locally occurs in the lower part of the Formation and is known in the literature as a cornéite (Stainier, 1907), i.e. millimetric magnetite, biotite and tourmaline porphyroblasts included in a silt-sized quartzite matrix rich in chlorite and ilmenite. South of Paliseul and Carlsbourg, this yellowish, greenish or variegated rock is usually de-cemented, and corresponds to the Paliseul Facies (Schistes aimantifères de Paliseul in Gosselet, 1888, p. 232) sensu Asselberghs (1946).

36Stratotype and sections. The historical outcrops along the disused vicinal railway along the Lesse River, north of Anloy, can be completed by the railway section, immediately south of the Poix-Saint-Hubert station. The type sections of the Quartzophyllades de Braux and Schistes de Joigny are situated on the western bank of the Meuse River valley between Joigny and Braux (France). In Belgium, the Braux Member is exposed in the disused quarries along the road N973, north-west of Bohan. The Joigny Member crops out along the road parallel to the Semois River north of Membre.

37Area and lateral variations. Between the Rocroi and Serpont inliers, in the vicinity of Gedinne, the red colour typical of the Oignies Formation disappears and the rock displays greenish, bluish or purplish-grey colours, together with the appearance of chlorite, ilmenite and biotite due to the local increase of metamorphism imprint. Therefore, the Oignies Formation is not identifiable and the facies d’Anloy (Asselberghs, 1940, p. 10, 1946, p. 59), which was considered as a distinct formation on the new geological maps of Wallonia, is dominant. The Anloy Formation can be traced south of the Vencimont Fault all along the northern limb of the Neufchâteau–Eifel Synclinorium. Around the Givonne Inlier, the Oignies Formation, though hardly distinguishable from the Saint-Hubert Formation, re-appears. The Braux Member is a lenticular body that can be traced only south-west of Petit-Fays and up to Arreux (France) where it disappears below the Jurassic cover. The Joigny Member is only developed between Bohan and Carlsbourg. Eastwards, it cannot be distinguished from the rest of the Anloy Formation.

38Thickness. The Anloy Formation reaches 1100 m in thickness in the Semois River valley (Belanger & Ghysel, 2017a) and decreases eastwards to c. 900 m near the Serpont Inlier (Beugnies, 1983). In their type area, the Braux and Joigny members are respectively 80 m and 400 m thick (Belanger & Ghysel, 2017a, b).

39Age. The Anloy Formation has not yielded any biostratigraphic elements, so its Lochkovian age is extrapolated from the lateral equivalent Oignies Formation.

40Use. The sandstone beds were locally used for building purposes.

41Main contributions. Gosselet (1888), Asselberghs (1940, 1946), Beugnies (1983), Hatrival & Beugnies (1973).

Figure 8. Illustration of some Lower Devonian units. A. Variegated siltstone of the Joigny Member of the Anloy Formation, section along the Meuse River at Joigny (France). Hand sample (width of the picture c. 5 cm). B. Massive sandstone beds with oblique stratification typical of the Bois d’Ausse Formation. Faubourg Sainte-Catherine, Huy in the Hoyoux River valley (courtesy of Jean-Marc Marion). C. Arkosic sandstone with fragments of fossil plants, Massuis Member of the Bois d’Ausse Formation. Hand sample from the Meuse River valley (width of the picture c. 8 cm).

Barrage Member – BAG

42See Hierges Formation.

Berlé Quartzite

43See Clervaux Formation.

Bième Member – BME

44See Acoz Formation.

Bois Chestion Member – BCS

45See Hierges Formation.

Bois d’Ausse Formation – BAU

46Origin of name. Section along the Namur–Arlon railway line through the crossing of the Bois d’Ausse close to Sart-Bernard, Grès du bois d’Ause in Gosselet (1873, p. 19). D’Omalius d’Halloy (1868, p. 514) mentioned the Bois d’Ose south of Namur where the sandstones of the Système du Grès de Montigny are particularly well developed.

47Description. The Bois d’Ausse Formation starts with the first grey, blue-grey or light-coloured quartzitic sandstone beds that overlie the green or variegated sandstone and siltstone of the Fooz Formation (Fig. 8B). The contact with the red facies of the overlying Acoz Formation is also clear-cut. Three members were defined in the Tréko River valley by Dejonghe et al. (1994c, p. 107), but their lateral extension seems to be limited, and their distinction is not possible eastwards in the Hoyoux River valley. These are, from base to top: the Bôlia, Tréko and Masuis members (Membre de Bôlia, Membre du Tréko, Membre des Masuis in Dejonghe et al., 1994c, p. 107). The Bôlia Member – BOL is characterised by thick beds of grey to grey-green quartzitic sandstone, usually arkosic, rich in cross-stratifications that are separated by thin beds of green to green-blue siltstone and shale. Its top includes a plurimetric unit of olive-green sandstone. The Tréko Member – TRK, consists of alternating thin beds of green sandstone and siltstone, reminiscent of the Fooz Formation (Delcambre & Pingot, 2014). The Masuis Member – MAS comprises lenticular beds of light grey to grey-beige quartzitic sandstone and arkosic sandstone that are separated by centimetric to decametric beds of grey shale. Some of the quartzite beds include shaly pebbles and plant fragments (Fig. 8C).

48Locally, the upper part of the Bois d’Ausse Formation displays a sequential character and was previously considered as a distinct unit, i.e. the Nonceveux Formation (Hance et al., 1992; Dejonghe et al., 1994d). It consists of a succession of thinning-upward sequences, ranging from 1.6 to 15 m in thickness, divided into a lower, light-coloured, sandy part, and an upper, grey, beige or reddish, silty and shaly one, but with no clear boundary (Fig. 9A). The base of the sequences is well marked, sometimes erosive and recurrences of sandy and/or silty beds are observed in the fine-grained parts. These lithologies were described as facies du Bois de Fraipont by Asselberghs (1946) and individualised as the Nonceveux Formation by Hance et al. (1992), based on the Nonceveux section in the Amblève River valley. Michot (1953) and Monseur (1959) pointed out the rhythmic character of the upper part of the Bois d’Ausse Formation at Huy on the northern limb of the Dinant Synclinorium. On the new geological maps of this part of the Dinant Synclinorium (Mottequin et al., 2021; Delcambre, 2023; Marion et al., in press), these rhythmical facies were not mapped distinctively. Therefore, it is here considered that they form the Nonceveux Member – NON of the Bois d’Ausse Formation.

49Stratotype and sections. As the historical Sart-Bernard section is incomplete and poorly exposed nowadays, Dejonghe et al. (1994c) proposed the Tréko River valley section at Vitrival as the stratotype that can be complemented by that of the Chevreuils River valley at Dave where the lowermost part of the Formation is better exposed. The type section of the Nonceveux Member is located on the right bank of the Amblève River valley, north of the eponymous village.

50Area and lateral variations. The Bois d’Ausse Formation is recognised on the northern and eastern flanks of the Dinant Synclinorium and in the Vesdre area, from Wiheries to Eupen. It is also recorded in the Bolland borehole (Graulich, 1975). The Nonceveux Member exists along the eastern limb of the Dinant Synclinorium (north of the Xhoris Fault), and in the Vesdre area. The Nonceveux Member is also recorded in the Bolland borehole (Graulich, 1975).

51Thickness. It is highly variable: 200–300 m south of Binche (Hennebert & Delaby, 2017), 150–170 m in the Bième River valley at Acoz (Delcambre & Pingot, 2000b), 100 m at the stratotype (Dejonghe et al., 1994c), more than 300 m in the Meuse River valley (Delcambre & Pingot, 2017), c. 300 m in the Hoyoux River valley (Mottequin et al., 2021), and 35 m in the Vesdre area (Hance et al., 1992). The Nonceveux Member is 110 m thick at the stratotype (Hance et al., 1992; Dejonghe et al., 1994d), 100–120 m thick at Pepinster (Laloux et al., 1996) and thins out westwards.

52Age. Based on palynology, Steemans (1989a) suggested a Lochkovian to late Pragian age for the Bois d’Ausse Formation, which spans the interval of the Siβ Zone to the Su Zone. In Huy, the shale of the Nonceveux Member yielded an assemblage indicative of the Paα Zone (Dejonghe et al., 1994d) whereas in Pepinster, the upper Lochkovian Z Zone is recorded. Hence the Nonceveux Member displays a diachronic age and becomes younger westwards (Steemans, 1989a).

53Use. This unit has been intensively quarried for granulate and building stone production.

54Main contributions. Bataille (1924), Asselberghs (1946), Michot (1953, 1969), Monseur (1959), Steemans (1981, 1989a), Hance et al. (1992), Dejonghe et al. (1994c, 1994d), Goemaere et al. (2012).

Figure 9. Illustration of some Lower Devonian units. A. Siltstone-sandstone alternations typical of the Nonceveux Member of the Bois d’Ausse Formation. Section along the Amblève River at Nonceveux. B. Typical facies of the Burnot Formation. Section along the Hoyoux River at Régissa (Marchin). C. Sequential deposits of red sandstone, siltstone and dolomitic shale in the Sainval Facies of the Burnot Formation. Sainval section in the Ourthe River valley north of Tilff.

Bois de Chaumont Formation – BCH

55Origin of name. Section located in the Bois de Chaumont south-east of the village of Presles, Formation du Bois de Chaumont in Delcambre & Pingot (2014, p. 23). The Bois de Presles Formation (Formation du Bois de Presles, as the Bois de Presles is the disused name for the Bois de Chaumont) was introduced by Sorel et al. (2013, p. 16–17) but was based on the unpublished version of the Tamines–Fosses-la-Ville geological map of Delcambre & Pingot (2014). In the meantime, the latter author modified this name, because it was preoccupied for a member of the Ordovician Fosses Formation (e.g. Martin, 1969; Verniers et al., 2002).

56Description. This unit begins with a conglomerate formed by millimetre- to decimetre-sized pebbles of quartz and quartzite, followed by beds of greenish sandstone, and greenish to blueish siltstone and shale.

57Stratotype and sections. Discontinuous outcrops in the Bois de Chaumont (also named Bois de Presles), between Presles and Le Roux.

58Area and lateral variations. The Bois de Chaumont Formation is known only from its type locality, in the Haine–Sambre–Meuse Overturned Thrust sheets, i.e. north of the Midi–Eifel Fault. Whereas its facies is reminiscent of that of the Fooz Formation known from the Dinant Synclinorium, the thermic maturity of the palynomorphs suggests that this unit is structurally closer to those of the Condroz Inlier, which is located to the north of the Midi–Eifel Fault (Steemans, 1994). Furthermore, it cannot be ruled out that it is an isolated outlier of the Fooz Formation.

59Thickness. c. 20 m.

60Age. Late Lochkovian, Siβ Interval Zone (Steemans, 1994), i.e. an age equivalent of the Fooz to Bois d’Ausse formations.

61Use. Very locally quarried as a building stone (Delcambre & Pingot, 2014).

62Main contributions. Lassine (1914), Fourmarier (1919), Michot (1928), Steemans (1994), Delcambre & Pingot (2014).

Bois des Collets Member – BCO

63See Wépion Formation.

Bois Godiau Formation – BGD

64Origin of name. Section at the Bois Godiau (or Godeau) locality, south of Bouffioulx, Formation de Bois Godiau in Delcambre & Pingot (2000b, p. 17).

65Description. The Bois Godiau Formation is a thick conglomerate with centimetre- to decimetre-sized pebbles of quartz, quartzite and dark slate embedded in a reddish sandstone or argillaceous sandstone matrix. This conglomerate rests unconformably on the Silurian basement.

66Stratotype and sections. Western bank of the Bième River valley, south of Bouffioulx near the Bois Godiau locality.

67Area and lateral variations. The Formation is only known from the type locality situated in the Haine–Sambre–Meuse Overturned Thrust sheets, i.e. north of the Midi–Eifel Fault. It could be an isolated outlier of the Rivière Formation (Middle Devonian).

68Thickness. Unknown with accuracy as only a couple of metres crop out in the type locality.

69Age. Late Emsian or Eifelian. Up to now, no dating element has been found in the conglomerate. Based on the facies, de Dorlodot (1890, 1893) correlated it with the Naninne Conglomerate of the Middle Devonian Rivière Formation (see Denayer et al., 2024).

70Use. Nil.

71Main contribution. Delcambre & Pingot (2000b).

Bôlia Member – BOL

72See Bois d’Ausse Formation.

Bouillon Facies

73See Villé Formation.

Braux Member – BRO

74See Anloy Formation.

Bure formation

75Disused unit, see Moulin de la Foulerie Formation.

Burnot Formation – BUR

76Origin of name. Section on the western flank of the Meuse River valley at Burnot, in front of the Lustin bridge, Poudingue de Burnot in d’Omalius d’Halloy (1839, p. 449).

77Description. The base of the Burnot Formation is defined by the first reddish (lie-de-vin-coloured in the literature) conglomerate bed overlying the greenish sandstone of the Wépion Formation (Fig. 9B).

78The Formation is typically made of rhythmical alternations of conglomerate, sandstone, siltstone and shale arranged either in cyclic or non-cyclic deposits (Corteel et al., 2004). The cyclic deposits start with conglomerate beds overlying an erosional surface and grading upwards to sandstone, then siltstone and shale. In some cycles, the basal conglomerate is reduced to a few centimetres of coarse-grained sandstone. The sandstone frequently displays oblique bedding or ripple marks and shale clasts. The shaly capping beds display occasional root traces, accumulations of thin plant debris or palaeosols (dolcretes); however, the fine-grained part of the cycle can be entirely missing due to erosion by the subsequent cycle (Corteel et al., 2004).

79The non-cyclic deposits are composed of gravely sandstone, sandstone and siltstone either coarsening-upward or without trends. Conglomerate and siltstone are proportionally less abundant in these non-cyclic deposits. Parallel and oblique laminations, clasts, erosive surfaces and ripple marks are commonly observed in the sandstone.

80The vertical succession of the deposits appears as an alternation of packages up to 10 m thick and 10–30 m thick packages of reddish shale, siltstone and sandstone (Delcambre & Pingot, 2017). The conglomerate and sandstone beds usually form lenses up to tens of metres in thickness. The conglomerate displays a reddish sandy matrix and centimetre to decimetre-sized pebbles (brown, black or red sandstone and quartzite, whitish quartz, black tourmalinite) that are usually well rounded but poorly sorted (some pebbles are 30 cm large). The sandstone is reddish or brownish and often has coarse-grained horizons of white quartz grains and pebbles. The siltstone and shale are finely micaceous, reddish or greenish or variegated.

81In the Meuse River valley, the coarse-grained lithologies are dominant but, eastwards, the fine-grained facies locally form a larger proportion of the Formation. In the Ourthe River valley (Tilff area), the conglomerate is very scarce (Fourmarier, 1910) and the Burnot Formation is largely dominated by cyclic alternations of red sandstone, variegated siltstone and shale, and frequent yellowish dolcretes (Fig. 9C). These lithologies correspond to the here introduced Sainval Facies.

82Eastwards, in the Vesdre River valley, the Burnot Formation is reduced to a tongue of conglomerate resting paraconformably on the Pragian rocks and previously named Vicht Formation (Vichter Konglomerat in Holzapfel, 1910, p. 210; Formation de Vicht in Dejonghe et al., 1991, p. 87) that is here considered as a local member (Vicht Member – VIC, see Figs 9–10 in Denayer et al., 2024). It consists in metric beds of conglomerate and conglomeratic sandstone containing centimetric to pluricentimetric pebbles of quartz, quartzite, sandstone and occasional tourmalinite with frequent siltstone intercalations. The wine-red colour is dominant but tends to fade away westwards with more and more greenish to greyish intercalations (Dejonghe et al., 1991). The Vicht Member appears as a series of finning-upwards sequences with erosive bases formed by a succession of 10–100 m wide lens-like bodies (Kasig & Neumann-Mahlkau, 1969).

83South of the Xhoris Fault, the colour of the conglomerate changes from red to green, greyish-green, yellowish or orange. This chromatic change is paralleled with the increase in bed thickness between the Aisne River and the Ourthe River valleys. In this area, Stainier (1994a, p. 91) introduced the Hampteau Formation (Formation de Hampteau) composed of the Hamoûle and Chaieneu members for the unit named Poudingue de Wéris by Gosselet (1873, p. 19) and Dupont (1885, p. 215). According to Barchy & Marion (2014), the establishment of a specific formation for the conglomerates observed at Hampteau is superfluous since they consider them to belong to the Burnot Formation. Recent geological mapping demonstrated that the Hamoûle Member is the local expression of the Hierges Formation whereas the Chaieneu Member is only a regional variation of the Burnot Formation. Therefore, it is considered here that the Hampteau Facies corresponds to the conglomerate of the Burnot Formation with variegated colours (Fig. 10A).

84West of the Meuse River valley, the top of the Formation contains a massive unit of homogeneous conglomerate with large pebbles. In the Eau d’Heure River and Sambre River valleys, it displays a variegated matrix and was described by Bayet (1894) and Anthoine (1919) who named it as the poudingue du Bois de Saucy (Bayet, 1894, p. 144), poudingue de Chevesne (Anthoine, 1919, p. M44) and poudingue de Cour-sur-Heure (Bayet, 1894, p. 143). Westwards, in the Honnelle River valley, near the French border, the same beds reach 30 m in thickness and the matrix is reddish (Foucher, 1966). This unit corresponds to the Caillou-qui-Bique Member – CQB (Fig. 10B) re-introduced by Marlière (1970, p. 13: Em 3 (Poudingue du Caillou-qui-Bique)) following Briart & Cornet (in Hanuise, 1882, p. 213: poudingue du Caillou qui bique).

85Remark. South of the Pepinster Fault, where the Burnot Formation is developed, the conglomeratic beds of supposed Emsian age were mapped under this name (e.g. Bellière, 2015; Marion & Barchy, in press, b; Marion et al., in press) but north of it, the Emsian is supposedly absent, the conglomeratic beds resting directly on the Pragian sandstones were mapped as the Vicht Formation (e.g. Laloux et al., 1996). The difference between both lithostratigraphic units is mostly the age: supposed Emsian for the Burnot Formation, Eifelian–Givetian for the Vicht Formation, regarded here as a member of the former (see above). However, in the Ourthe River valley (Hampteau), the conglomerate is Eifelian (Stainier, 1994a). Therefore, the Burnot Formation should be considered as post-Emsian in the north-eastern part of the Dinant Synclinorium. As a consequence of this age getting younger north-eastwards, the Burnot Formation passes in continuity to the Vicht Conglomerate. Knowing that the conglomeratic facies are extremely diachronous, it is more reasonable to consider the Vicht Member as a younger extension of the Burnot Formation towards the east and north.

86Stratotype and sections. The original type locality is a discontinuous section along the Burnot River on the western bank of the Meuse River valley. A good section is located in the latter valley along the road Namur–Dinant (N92) at Profondeville, 200 m north of the Lustin bridge and continuing along a path on top of the valley western flank. The top of the Formation can be observed on the eastern side of the Meuse River valley, south of the Lustin bridge, along the road from Lustin to Godinne. Good exposures exist in the Hoyoux River valley, north-east of Marchin, and in the Ourthe River valley north of Tilff (Sainval Facies). The Hampteau Facies are exposed along the Ourthe River, south of Hampteau, and in Roche-à-Frêne in the Aisne River valley. The Caillou-qui-Bique Member crops out in the eponymous locality in the Honnelle River valley, north of Roisin. The Vicht Member crops out in the Vicht River valley south-east of Stolberg in Germany. The section is however discontinuous, and Dejonghe et al. (1991) proposed the section in the Helle River south of Eupen as a parastratotype.

87Area and lateral variations. The Formation is known all along the northern limb of the Dinant Synclinorium from Roisin to Tilff, along its north-eastern flank up to the Xhoris Fault and in the Vesdre area. South of the Xhoris Fault and up to the Ourthe area south of Hotton, the Hampteau Facies develops then fades away westwards (Dupont, 1885). The Vicht Member is known from the Aachen area (Germany) to Fraipont and in the Theux Window. The proportion of conglomerate is variable and tends to decrease towards the north-east, where the Sainval Facies is almost devoid of coarse-grained lithologies. In Fechereux and in the Ry de Mosbeux, the Formation is reduced to a metric bed of conglomerate with quartz pebbles and plant remains (Asselberghs, 1955; Liégeois, 1955). East of Gomzée, the development of the conglomerate increases irregularly. The upper conglomeratic unit (Caillou-qui-Bique Member) tends to individualise west of the Eau d’Heure River valley.

88Thickness. More than 500 m thick in the type section (Stainier, 1994b); the Formation thickness decreases eastwards: 350 m in the Hoyoux River valley (Mottequin et al., 2021), 240 m in the Amblève River valley (Asselberghs, 1946; Marion et al., in press), 250 m in the Aisne River valley, only 45 m north of the Xhoris Fault (Marion & Barchy, in press, b). In the Vesdre area, the Vicht Member reaches 80 m in Pepinster, and decreases to less than 5 m west of Verviers (Laloux et al., 1996), 2 m in the Theux Window (Marion et al., in press) and only 1.6 m in the Soumagne borehole (Graulich, 1977). In the western part of the Dinant Synclinorium, the thickness also varies considerably: 300 m in the Eau d’Heure River valley (Delcambre & Pingot, 2000a), 200 m in the Honnelle River valley (Hennebert & Delaby, in press), including 30 m for the Caillou-qui-Bique Member (Foucher, 1966).

89Age. Up to now, no biostratigraphic element allows to date the Burnot Formation, especially in the stratotypic area (Stainier, 1994b). A late Emsian to early Eifelian age was inferred only through the age of the overlying and underlying formations. The top of the underlying Wépion Formation belongs to the upper Emsian FD Zone (Steemans et al., 2002) and the base of the overlying Rivière Formation yielded conodonts characteristic of the Eifelian partitus Zone (Bultynck, 1991a). In Hampteau, some fine-grained beds of the Hampteau Facies yielded miospores indicative of the Pro–Vel zones suggesting an Eifelian age (Lessuise et al., 1979; Stainier, 1994a). In the Heusy section, shales intercalated within conglomerate beds and above it both yielded palynological assemblages indicative of the Lem Zone, i.e. earliest Givetian (Hance et al., 1992, 1996). In Eupen and Goé, the shaly beds, within and above the conglomerate of the Vicht Member yielded a palynological assemblage devoid of the spore Geminopsora lemurata, and therefore is referred to the ‘pre-Lem’ AD Biozone, i.e. latest Eifelian in age (Hance et al., 1996).

90Use. The coarse-grained sandstone was used during the Neolithic for the millstone production (Picavet, 2015). Massive blocks of conglomerate have been used in the Neolithic for the erection of the famous megaliths around Wéris. In more recent times, the rocks were used for building purposes and for the roadbeds.

91Main contributions. Gosselet (1873), Bayet (1894), Anthoine (1919), Van Tuijn (1927), Asselberghs (1946), Asselberghs (1955), Liégeois (1955), Foucher (1966), Kasig & Neumann-Mahlkau (1969), D’Heurs (1970), Breil-Schollmayer (1989), Hance et al. (1989, 1992, 1996), Dejonghe et al. (1991), Stainier (1994a, b), Laloux et al. (1996), Neumann-Mahlkau & Ribbert (1998), Corteel et al. (2004).

Figure 10. Illustration of some Lower Devonian units. A. Conglomerate with greenish-grey matrix of the Hampteau Facies of the Burnot Formation. Neolithic megaliths at Wéris. B. Caillou-qui-Bique Rock in the Honnelle River valley, Caillou-qui-Bique Member of the Burnot Formation. C. Red siltstone of the Chooz Formation. Section along the Viroin River at Vireux (width of the picture c. 4 cm).

Caillou-qui-Bique Member – CQB

92See Burnot Formation.

Chaieneu member

93Disused member of the former Hampteau formation, now integrated into the Burnot Formation.

Chooz Formation – CHO

94Origin of name. After the village of Chooz, located in a meander of the Meuse River (France), d2c Schistes rouges de Chooz in Gosselet (1882, unpaginated explanatory booklet).

95Description. The Chooz Formation, initially called roches rouges de Vireux by Gosselet (1868) (more or less equivalent to the Grès, et schistes rouges de Winenne introduced by the Conseil de Direction de la Carte, 1892, p. 228), is essentially made of red and green shale (enclosing centimetre- to decimetre-thick beds of similarly coloured quartzite) that alternate with red and green sandy units that can reach several metres in thickness.

96In the Meuse River valley, Godefroid & Stainier (1994a) distinguished two subunits. The lower one (c. 50 m thick) comprises argillaceous or quartzitic sandstone occurring as thick masses separated by red and green, rarely grey, shale and siltstone (Fig. 10C). The lower sandstone includes some thin carbonate horizons and yielded some terebratulide brachiopods, bryozoans and bivalves. The upper subunit is much thicker (270–280 m) and consists of red and green shale and siltstone that incorporate beds or lenses of similarly coloured sandstone up to 10–14 m thick.

97Stratotype and sections. Disused Mont Vireux quarry on the left bank of the Meuse River at Vireux-Molhain (France) for the contact with the underlying Vireux Formation; Vireux-Molhain–Mazée road (D47), west of the crossroads with the Givet road (RN51), for the contact with the overlying Hierges Formation (Godefroid & Stainier, 1988; Godefroid & Stainier, 1994a).

98Area and lateral variations. South and south-eastern flanks of the Dinant Synclinorium up to the Xhoris Fault. In the Ourthe River valley and eastwards, the Chooz Formation is overlain by the conglomerate of the Hampteau Facies of the Burnot Formation. In this area, the first conglomeratic bed, rather than the last red-coloured bed, is used to define its top.

99Thickness. It ranges between 320 and 330 m in the Meuse River valley (Godefroid & Stainier, 1988) and to the west (Marion & Barchy, 1999), and reaches 300 m to the east (Barchy & Marion, 2014).

100Age. Traditionally considered as corresponding to the middle part of the Emsian following the tripartite subdivision of this stage (e.g. de Dorlodot, 1901; Conseil géologique, 1929) but elements for a precise dating are lacking. The Vireux and Chooz formations constitute a thick mass of rocks almost devoid of fossils (Godefroid & Stainier, 1988) that is comprised between the fossiliferous and well-dated Ruisseau de la Forge (Pesche Member) and Hierges formations.

101Use. In the past, the sandstone beds were used locally for roadbed.

102Main contributions. Gosselet (1868, 1871), Godefroid & Stainier (1988, 1994a).

Clervaux Formation – CLE

103Origin of name. After the town of Clervaux in Luxembourg, Schistes rouges de Clervaux in Gosselet (1885, p. 269).

104Description. The Formation starts with olive-green and greyish shale and siltstone with greenish sandstone lenses and beds. The fine-grained lithologies typically have a silk-soft touch. Upwards, the reddish colour appears in the shale, but the sandstone keeps its greenish or greyish colour (Dejonghe, 2020). In the upper part of the Formation, small limonitic nodules aligned in thin horizons occur. Usually light grey, quartzitic and argillaceous sandstone beds with flaser-bedding occur sporadically and locally (called Härebësch Member – HAR, Membre de Härebësch in Dejonghe, 2021, p. 23), and are better individualised in Luxembourg (Dejonghe, 2021). At the top of the Formation, a second package of sandstone beds form a distinct unit called Quarzites [sic] de Berlé (Gosselet, 1885, p. 265) in Luxembourg, Koblenzquartzit or Emsquartzit in Germany (Ribbert et al., 1992) and Quarzites [sic] de Traimont (Gosselet, 1885, p. 293) in Belgium (Ghysel, 2023). The Berlé Quartzite (called Q1 in Asselberghs, 1946) is made of lenticular beds of argillaceous and quartzitic sandstone with planar and oblique stratifications, mud chips, dissolved coquinas and bioturbations (Michel et al., 2010) (Fig. 11A). The quartzitic horizon is laterally very discontinuous and, where not developed, the overlying Wiltz Formation rests directly on the Clervaux Formation. Similar beds also occur within the upper third of the Clervaux Formation (Q2 and Q3 in Asselberghs, 1946).

105Stratotype and sections. The section along the road CR325, south-west of the Clervaux town (Luxembourg), offers a good exposure of the Formation, including its contact with the underlying Our Formation. The upper part of the Clervaux Formation and the Berlé Quartzite is exposed along the N10 road, south of the bridge on the Our River at Dasbourg-Pont (Luxembourg). In Belgium, the Clervaux Formation is poorly exposed, but a correct section is situated along the road N848, south of Volaiville, where the quartzite was extracted in small quarries (Ghysel, 2023). The Härebësch Member is exposed in disused quarries along the Wiltz River near Weidingen (Luxembourg, see Dejonghe, 2021).

106Area and lateral variation. Neufchâteau–Eifel Synclinorium, east of Ebly and eastwards in Luxembourg and Germany (Eifel). The red colour, dominant in the western part of this synclinorium, tends to fade eastwards where the green colour dominates. The unit is also present in some synclines east of the Stavelot–Venn Inlier near Bullange (Büllingen) and Manderfeld.

107Thickness. In the type area, the Clervaux Formation reaches 500 m in thickness. It decreases westwards to c. 200 m at the border between Luxembourg and Belgium and increases eastwards to 700–800 m at the Germany–Luxembourg border (Dejonghe, 2020). The Berlé Quartzite is 2–5 m thick in Belgium (Ghysel, 2023) and its thickness reaches 8–9 m in Luxembourg.

108Age. The Clervaux Formation yielded spores indicative of the FD and AP zones (Steemans et al., 2000), i.e. middle to late Emsian in age. The Berlé Quartzite yielded an upper Emsian macrofauna and therefore is equivalent to the upper part of the Clervaux Formation (Asselberghs, 1941).

109Remark. In the German lithostratigraphic terminology, the Klerf Schichten (Klerf beds) cover a wider package of rocks than the Luxembourger and Belgian Clervaux Formation, as this unit covers the shaly upper part of the Our Formation. Recent investigations of the palynological content in Germany confirm that the base of the Klerf-Schichten might be older (early–middle Emsian, Steemans et al., 2023). Note also that the German Stratigraphic Commission considers the Berlé Quartzite as a formation (Jansen, 2016).

110Use. The quartzite was intensively quarried both in Belgium and Luxembourg for building purposes. The sandstones were also quarried for aggregate production.

111Main contributions. Asselberghs (1913, 1946), Lucius (1951), Godefroid & Stainier (1982), Franke (2006), Ribbert (2007), Michel et al. (2010).

Figure 11. Illustration of some Lower Devonian units. A. Coarse-grained quartzitic sandstone with mud chips of the Berlé Quartzite. Hand sample from Berlé (width of the picture c. 5 cm). B. Microconglomeratic sandstone with lithic clasts, ‘arkose’ of the Haybes Member. Hand sample from Lahonry quarry (width of the picture c. 10 cm). C. Ombret Conglomerate at the base of the Fooz Formation. Pierre Falhotte, Ombret in the Meuse River Valley.

Dave member

112Disused term equivalent of the Waimes Member, see Fooz Formation.

Eau Noire Member – ENR

113See Moulin de la Foulerie Formation.

Écluse Member – ECL

114See Vireux Formation.

Fépin Formation – FEP

115Origin of name. After the locality Roches à Fépin, on the eastern flank of the Meuse River valley at Haybes (France), Poudingue de Fepin in Dumont (1836, p. 334).

116Description. The Fépin Formation groups two units of varying thickness: the basal conglomerate—poudingues de Fepin and poudingue pisaire de Fepin (Dumont, 1848, p. 88, p. 194), poudingue de Linchamps (Gosselet, 1888, p. 207), poudingue de Tournavaux (Gosselet, 1888, p. 212), or Poudingue de Muno (Lecompte, 1967, pl. 5)—and a sandstone unit, known in the literature as arkose d’Haybes (Gosselet, 1884a, p. 194) and arkose de Haybes (Renard, 1884, p. 119). The arkose de Macquenoise (Picavet et al., 2017, p. 270) (also named the Macquenoise sandstone in Picavet et al., 2018, p. 29) denotes a particular facies of the second unit.

117Around the Rocroi Inlier, the Formation begins with the Linchamps Conglomerate, a poorly sorted conglomerate that consists of an argillaceous sandstone matrix enclosing boulders and pebbles of dark quartzitic sandstone and quartz. This basal unit underlines the very irregular surface of the Caledonian unconformity. The conglomerate displays finning-upwards sequences with erosive base. Coarse-grained sandstone, with occasional planar or oblique stratifications, forms metre-thick lenses within the conglomerate. Around the Givonne Inlier, the conglomerate displays less matrix and the boulders are often bound by a siliceous cement.

118Upwards, lenses and beds of fine-grained sandstone increase in frequency, passing to the Haybes Member – HAY. The sandstone is greyish or blueish, contains up to 6–10% of feldspar and alternates with dark or greenish sandy shale. The matrix of the coarser-grained facies is often kaolinitic (Fig. 11B). Shale and sandstone yield rare and poorly preserved fossils (e.g. bivalves, brachiopods). Rare impure limestone forms thin beds locally. Around the Givonne Massif, the upper part of the Formation corresponds to the Roche à l’Appel Member – RAA (Membre de la Roche à l’Appel in Belanger & Ghysel, 2017b, p. 14), a lenticular unit of dark green quartzitic sandstone with oblique stratifications alternating with argillaceous micaceous sandstone and dark grey shale.

119Stratotype and sections. The sections situated near Fépin and Haybes (France) are discontinuous but illustrate the facies variations (Meilliez, 1984, 1989). Godefroid et al. (1982) defined the stratotype of the Fépin Formation in the Lahonry quarry, south of Couvin. The Linchamps Conglomerate is defined in the disused quarry at Muno (Godefroid & Cravatte, 1999) whereas the Roche à l’Appel Member is defined in the eponymous locality (Belanger & Ghysel, 2017b).

120Area and lateral variations. The Fépin Formation covers the Cambrian and Ordovician rocks of the Rocroi, Givonne and Serpont Inliers. It was mapped along the south-western digitation of the Stavelot–Venn Inlier but the facies corresponds to the Waimes Member and, therefore, should be included in the Fooz Formation rather than in the Fépin Formation between Dochamps and Manhay and near Harre. The Linchamps Conglomerate passes to the Quareux Conglomerate whereas the Haybes Member passes to the lighter-coloured Waimes Member. Meilliez & Lacquement (2006) described very strong variations of facies and thickness in the Fépin locality. Similar variations have been documented in Lahonry (Godefroid et al., 1982) and elsewhere.

121Thickness. The conglomeratic part is very variable in thickness, even over very short distances, and strongly depends on the palaeo-topography of the Caledonian basement. It varies from a few metres up to 70 m in Fépin (Meilliez, 1984), but usually c. 20 m in average. The Fépin Formation varies from 20 m on the southern edge of the Rocroi Inlier, to 50 m on its northern edge and on the Givonne Inlier (Belanger & Ghysel, 2017b), to 30 m on the south-western edge of the Stavelot–Venn Inlier (Dejonghe, 2008; Dejonghe & Hance, 2008). It is missing around the Serpont Inlier. The Roche à l’Appel Member is 0–80 m thick (Belanger & Ghysel, 2017b). The Haybes Member varies in thickness from 0 m to a few tens of metres (Meilliez, 1984).

122Age. The Fépin Formation, which is younger northwards, yielded a poorly preserved miospore assemblage indicative of the R Zone in Lahonry and of the N Zone in Willerzie (Steemans, 1982a, b, 1989a).

123Use. The conglomerate is still locally used (Lahonry, Fépin) for aggregates and for building purposes. The coarse-grained sandstone has been used since the Neolithic to produce millstones (Picavet et al., 2017).

124Main contributions. Gosselet & Malaise (1868), Gosselet (1884a), Renard (1884), Bailly (1936), Anthoine (1940a), Asselberghs (1946), Godefroid (1982), Steemans (1982a), Meilliez (1984, 1989, 2006), Meilliez & Mansy (1990), Meilliez & Blieck (1994a).

Fooz Formation – FOO

125Origin of name. Section located in the Potisseau River valley at Fooz, a hamlet of Wépion, Psammites et schistes compactes de Fooz in Gosselet (1873, p. 5).

126Remarks. In the northern parts of the Dinant Synclinorium as well as in the Vesdre and Theux areas, Hance et al. (1992) and Dejonghe et al. (1994e, 1994f) distinguished two formations at the base of the Devonian sequence: the Fooz Formation to the west and the Marteau Formation to the east. Both units display the same dominant siliciclastic facies but differ by their dominant colour. The Fooz Formation is supposed to be greenish whereas the Marteau Formation is supposed to be reddish. Geological mapping of these formations demonstrated that on the one hand red beds exist in the Fooz Formation and on the other hand green or variegated beds are developed within the Marteau Formation. The distinction between the two is therefore only geographical, with the inconvenient that both units were recognised in the Vesdre area (Goé Tectonic Unit, Goemaere et al., 1997). It is here proposed that only one unit should be preserved. Psammites et schistes compactes de Fooz is the older designation (Gosselet, 1873). The Schistes bigarrés et psammites du Marteau introduced later by Gosselet (1888, p. 258) is therefore a subsequent synonym. However, the Psammites de Fooz stricto sensu (i.e. the beds overlying the conglomerate and so-called arkose) form a unit rather well individualised and deserve a formal definition. The Marteau Member is here introduced to cover the fine-grained variegated sandstone unit forming the upper part of the Fooz Formation.

127Description. The Formation rests unconformably on the lower Paleozoic basement and starts with a conglomerate named Ombret Conglomerate (Poudingue d’Ombret in Gosselet, 1873, p. 19; Mourlon, 1876, p. 327) in western areas and Quareux Conglomerate (poudingue de Quarreux in Gosselet, 1888, p. 253) in eastern areas. Both are characterised by pebble-supported conglomerate with centimetric to decimetric quartz and quartzite pebbles in a very hard greyish to greenish quartzitic matrix (Fig. 11C). Dark sandstone and tourmalinite pebbles also occur. The conglomerate tends to fade away in some places, passing to coarse-grained sandstone. On the contrary, it locally becomes very coarse-grained with poorly rounded sub-metric blocks (e.g. Ninglinspo River valley). The conglomerates deposited in fluviatile settings (Graulich, 1951; Neumann-Mahlkau, 1970). Note that the Ombret Formation was introduced by Martin et al. (1970) for an Ordovician unit of the Condroz Inlier (see Verniers et al., 2002).

128Where developed, the conglomerate passes upwards to light-coloured, kaolinitic coarse-grained sandstone or micro-conglomerate known in the old literature as arkose: e.g. Arcose von Weims in Kayser (1870, p. 850), Arkose de Dave in Gosselet (1873, p. 5), arkose de Weismes in Gosselet (1888, p. 253, 255), grès et arkoses de Gdoumont in Maillieux & Demanet (1929, p. 122, table 2), arkoses et grès de Gdoumont in Asselberghs (1943, p. 3). It should be noted that these lithologies are almost devoid of feldspars, but patches of whitish clayey material are mostly composed of weathered slate fragments and less than 5% of weathered feldspars (Michot, 1969). The Waimes Member – WAI is composed of kaolinitic coarse-grained sandstone with few micro-conglomeratic recurrences and siltstone intercalations (Fig. 12A). Centimetric pyrite cubes are frequent. The siltstone and fine-grained sandstone, beige in colour, have yielded a diverse fauna (brachiopods, corals, bivalves, trilobites) preserved as steinkerns. These facies display a clear marine influence. On the northern flank of the Dinant Synclinorium, they were named Arkose de Dave but as the lithologies are similar and the thickness rapidly decreasing westwards, it is preferable to give up this denomination. Note that the name schistes de Dave was proposed by Michot (1932, p. B136) for designating a Silurian formation in the Condroz Inlier (see Verniers et al., 2002).

129The upper part of the Fooz Formation is largely dominated by variegated fine-grained siliciclastics grouped in the Marteau Member – MAR corresponding to the Psammites de Fooz in the literature. Olive-green and variegated fine-grained sandstone, argillaceous or not, and siltstone alternate in the lower part of the Member. They are arranged in fining-upward sequences that begin with poorly sorted sandstone with shale clasts and small quartz pebbles, oblique stratifications and lenses, and that end with shale displaying desiccation cracks. The reddish colour progressively appears upwards. The upper part of the Member is richer in well-sorted sandstone beds that commonly display coarsening-upward trend and mega-ripples. The numerous horizons with dissolved carbonate nodules (centimetric to decimetric in size) give a cellular aspect to the Formation. These nodules are interpreted as concretions within calcrete and are therefore of paedogenetic origin (Stroink & Simons, 1995; Goemaere et al., 1997) (Fig. 12B). Silcretes and ferricretes are also developed (Goemaere et al., 2012). The Member reflects the depositional environment of an alluvial plain with braided rivers evolving towards a coastal plain with wandering meanders (Goemaere et al., 1997).

130Along the south-eastern edge of the Stavelot–Venn Inlier, the Marteau Member displays blueish to purple colour, due to slight metamorphism here named as the Reinhardstein Facies (Fig. 12C).

131Stratotype and sections. The stratotype designated for the Fooz Formation is situated along the Chevreuils River in Dave (Dejonghe et al., 1994e) where both the lower and upper boundaries are exposed, as well as the Dave member introduced by Dejonghe et al. (1994e) that included the Poudingue d’Ombret and the Arkose de Dave. The basal beds are exposed in Ombret (Pierre Falhotte, Fig. 11C) and in the Amblève River valley in the Fond de Quareux. The type section of the Marteau Member is situated along the Helle River south of Eupen (Dejonghe et al., 1994e) because the historical section in Spa (Marteau locality) is too discontinuous and strongly tectonised. The Waimes quarry and nearby section along the former railway acts as a composite type section for the Waimes Member. The Reinhardstein Facies is exposed in the Warche River valley near the medieval Reinhardstein castle.

132Area and lateral variations. The Formation is present in the Vesdre area, around the Stavelot–Venn Inlier and the Theux Window. It also occurs along the northern limb of the Dinant Synclinorium between Wihéries and Engis, and along its north-eastern limb between Tancrémont and Dochamps. The Marteau Member is also recorded in the Bolland borehole (Graulich, 1975). The Bois de Chaumont Formation is a lateral equivalent resting locally on the Condroz Inlier north of the Midi–Eifel Thrust Fault.