- Home

- Volume 22 (2019)

- number 1-2

- Cabindachanos dartevellei gen. and sp. nov., a new chanid fish (Ostariophysi, Gonorynchiformes) from the marine Paleocene of Cabinda (Central Africa)

View(s): 3000 (49 ULiège)

Download(s): 601 (10 ULiège)

Cabindachanos dartevellei gen. and sp. nov., a new chanid fish (Ostariophysi, Gonorynchiformes) from the marine Paleocene of Cabinda (Central Africa)

Attached document(s)

Annexes

Abstract

The osteology of Cabindachanos dartevellei gen. and sp. nov., a fossil fish from the marine Danian or early Selandian deposits of Landana (Cabinda Territory, Central Africa), is here studied in detail. This fish is known by only one partially preserved specimen that shows typical characters. The opercle is greatly hypertrophied. The preopercle has a very broad dorsal limb and a long narrower ventral limb. There is a wide plate-like suprapreopercle. The lower jaw is deep, with a well-marked coronoid process formed by the dentary. The articulation between the quadrate and the mandible is located before the orbit. The first supraneurals are enlarged. These characters indicate that C. dartevellei belongs to the family Chanidae (Teleostei, Gonorynchiformes). Cabindachanos dartevellei differs from all the other known fossil or recent chanid fishes by the gigantic development of its opercle and by the loss of the subopercle. The straight angle formed by the two limbs of the preopercle and the well-developed posterior median crest of the supraoccipital indicate that C. dartevellei belongs to the subfamily Chaninae and the tribe Chanini.

Table of content

1. Introduction

1A diverse and very rich paleontological material from marine Upper Cretaceous and Paleogene deposits was discovered by the Belgian explorer and paleontologist Edmond Dartevelle during the two expeditions (1933 and 1937-38) that he conducted in the Lower Congo Basin and in the Cabinda Territory. The numerous fossil fishes that he found there were described in three monographs (Dartevelle & Casier, 1943, 1949, 1959). However, some fish remains among the recorded material were left as undetermined samples and were not mentioned in the three monographs.

2One of these undescribed specimens was labelled by Edgar Casier as “Neopterygii indéterminé”. It is a member of the teleostean order Gonorynchiformes and of the family Chanidae. The aim of our paper is to describe this sample and to determine its relationships.

2. Stratigraphy

3The specimen was discovered in 1937 in the Landana cliff section, a marine Paleogene fossil site located in the Cabinda enclave, a province of Angola. This fossil site, currently located on the west African coast at 2 to 3 km south of the Shiloango river mouth (GPS coordinates: 05° 13’ S, 12° 07’ E), forms part of the Paleogene marine margin of the Congo Basin (see Dartevelle & Casier, 1943, p. 48, fig. 23).

4The lithological sequence of the Landana section has been subdivided into 32 sedimentary layers (“couches” in Dartevelle & Casier, 1943). The bio- and chemostratigraphic context of these layers has recently been unraveled in order to refine their age constraints (Solé et al., in press). This study has revealed the almost complete absence of Danian deposits, contrary to prevailing interpretations for over than half a century. The Danian is probably absent or reduced to a single layer (layer 1). The Landana section clearly includes the early Selandian (layers 2-12), the Thanetian (layers 13-18), the Thanetian-Ypresian transition (layers 19-24), the early Ypresian (layers 25-28), and the Lutetian (29-31). Layer 32 is a chert bed that might correspond to a major Lutetian denudation event in the Congo Basin (De Putter et al., 2016).

5Interestingly, the specimen described herein is one of the rare finds coming from layer 1 and is thus possibly Danian or early Selandian in age. The age of this layer cannot be more accurately determined because of the lack of data. Layer 1 yielded only three elasmobranchs (Odontaspis speyeri, Myliobatis dixoni, and ?Charcharias substriatus) and two planktonic foraminiferal taxa (Parasubbotina pseudobulloides and Subbotina triloculinoides) which are of poor biostratigraphic value (Solé et al., in press).

3. Material and methods

6The material studied herein belongs to the paleontological collections of the Royal Museum for Central Africa (MRAC, Tervuren, Belgium), Department of Geology and Mineralogy. The sample was observed with a stereomicroscope Leica MZ8. The drawings of the figures were made by the first author (L. T.) with a camera lucida. Aspersions with ethanol were used to improve the observations. Material for comparison comes from the Musée National d’Histoire Naturelle, Paris (MNHN), from the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences (IRSNB) and from the Capasso registered collection in Chieti, Italy (CLC).

4. Anatomical abbreviations used in the text figures

7AN: angular; ANT: antorbital; ASPH: autosphenotic; DN: dentary; DSPH: dermosphenotic; EPI: epiotic (= epioccipital); FR: frontal; IOP: interopercle; IORB 1-4: infraorbitals 1 to 4; MX: maxilla; NA: nasal; OP: opercle; PA: parietal; QU: quadrate; PMX: premaxilla; POP: preopercle; PT: posttemporal; PTE: pterotic; RART: retroarticular; SN 1-7: supraneurals 1 to 7; SOC: supraoccipital; SOP: subopercle; SPOP: suprapreopercle; ext. c.: extrascapular sensory commissure; l.: left; pop. c.: preopercular sensory canal; ot. c.: otic sensory canal; r.: right; soc. cr.: supraoccipital crest; sorb. c.: supraorbital sensory canal.

5. Systematic paleontology

8Division Teleostei Müller, 1845

9Infracohort Ostariophysi Sagemehl, 1885

10Series Anotophysi Rosen & Greenwood, 1970

11Order Gonorynchiformes Regan, 1909

12Suborder Chanoidei Berg, 1940

13Family Chanidae Jordan, 1887

14Genus Cabindachanos gen. nov.

15Type species. Cabindachanos dartevellei gen. and sp. nov. (here designated).

16Diagnosis. As for the species (monospecific genus)

17Etymology. The generic name refers to the Cabinda Territory (Central Africa) and to the genus Chanos.

18Cabindachanos dartevellei gen. and sp. nov.

19Diagnosis. Small chanid differing from the other members of the family by its greatly hypertrophied opercle and by the loss of the subopercle. Parietals reduced and broader than long. Supraoccipital with a well-developed posterior median crest. Preopercle with a broad dorsal limb and a long narrow ventral limb. Dorsal and ventral limbs of preoperple forming a straight angle. Large plate-like suprapreopercle. Two greatly enlarged elements within the anterior supraneurals. Scales cycloid, longer than deep, with thin and horizontally oriented circuli.

20Etymology. The specific name is given in honour of Edmond Dartevelle (1907-1956), a famous Belgian paleontologist and explorer, who has greatly contributed to the scientific knowledge of Central Africa.

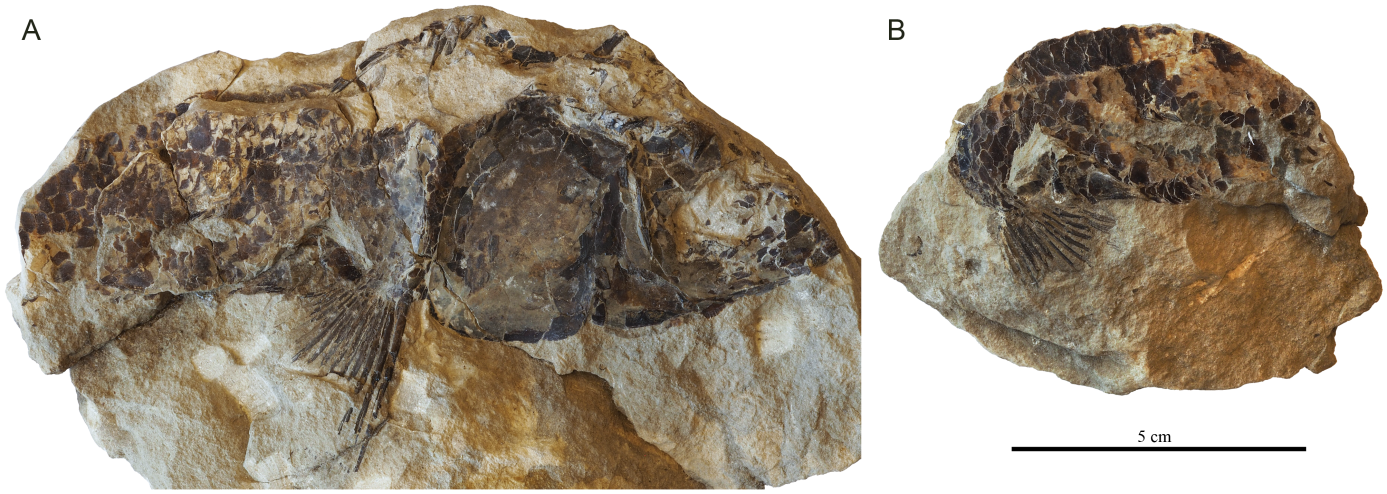

21Holotype. Specimen MRAC RG 4629 (collected in 1937 by E. Dartevelle at Landana, Cabinda Territory, layer 1, marine Danian or early Selandian, Lower Paleocene [N° 4108 in Dartevelle’s registry]). The sample is composed of three pieces belonging to the same fish: (a) a partly preserved skull, the pectoral fin, and the beginning of the body [right side, length: 125 mm] (Fig. 1A); (b) the counterpart of the pectoral fin and the beginning of the body [right side, length: 67 mm] (Fig. 1B); (c) the counterpart of a part of the opercle (Fig. 3A).

22Figure 1. Cabindachanos dartevellei gen. and sp. nov. Holotype MRAC RG 4629; (A) head, pectoral fin and beginning of the body (right side); (B) pectoral fin and beginning of the body (right side, counterpart) [copyright IRSNB].

23Osteology

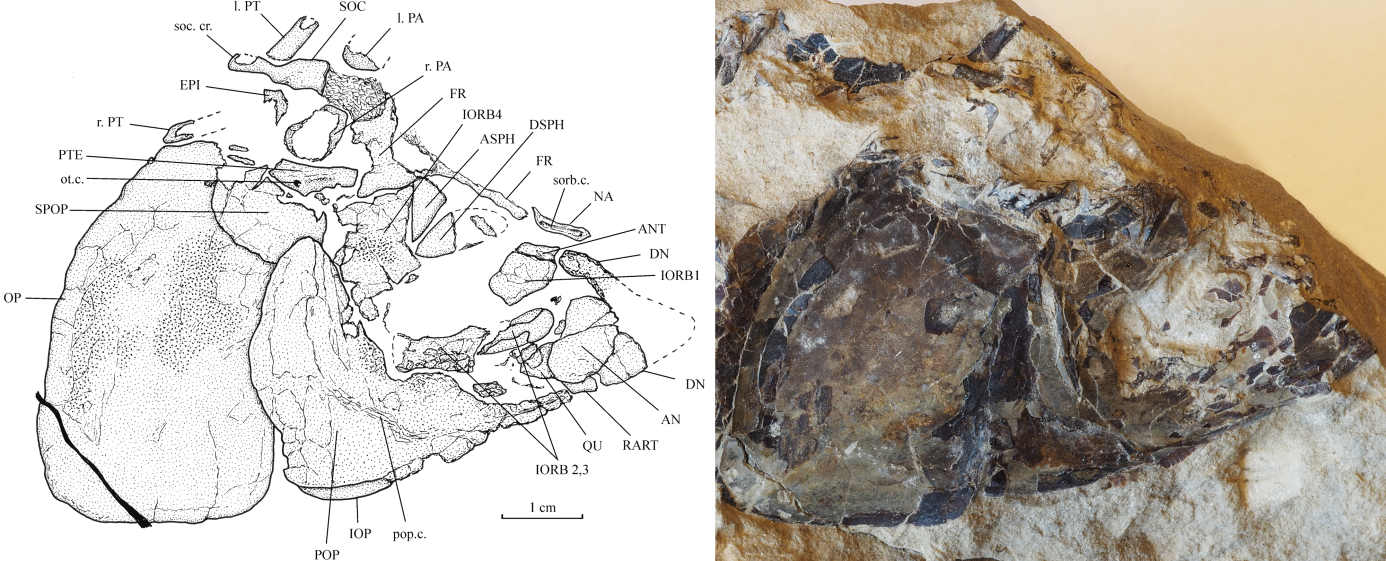

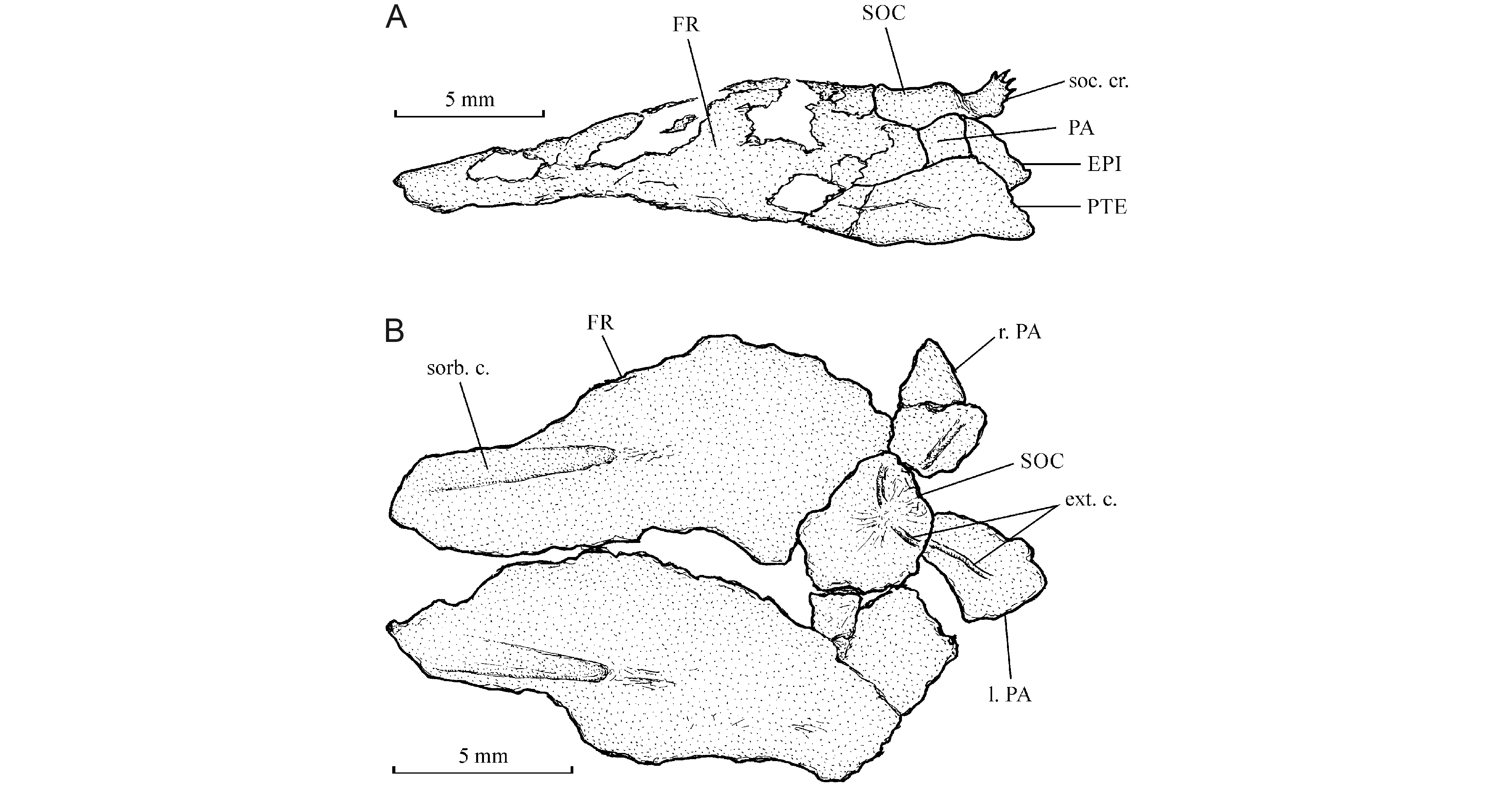

241. The skull (Fig. 2)

25The head is incompletely preserved. The ethmoid region, a great part of the skull roof and the upper jaw are missing.

26Figure 2. Cabindachanos dartevellei gen. and sp. nov. Skull of holotype MRAC RG 4629.

27The nasal is a small narrow tubular bone that carries the most anterior portion of the supraorbital sensory canal. Only a posterior fragment and the lateral margin of the right frontal are present. The right parietal, a fragment of the left parietal, the right pterotic and the right epiotic (= epioccipital) are also preserved; these are small bones. The right parietal is broader than long. A trace of the otic sensory canal is preserved on the pterotic. The skull is lateroparietal, the two parietals being separated by the supraoccipital. The strongly developed acuminate postorbital process of the autosphenotic is visible under the frontal. The supraoccipital bears a well-marked posterior median crest that greatly extends behind the rear of the skull.

28The posterior region of the lower jaw is deep, with a strongly developed coronoid process formed by the upper branch of the dentary. A large angular and a smaller autogenous retroarticular are also visible. The anterior region of the mandible is missing.

29A part of the quadrate is the only preserved element of the palatine arch.

30Six elements of the circumorbital series are present. The antorbital is a small bone that is sutured with the upper margin of the rather wide first infraorbital. The second and the third infraorbitals are longer but less deep. The fourth infraorbital is a large plate-like bone ornamented with very small tubercles. Two fragments of a long dermosphenotic are also present just before the autosphenotic. No supraorbital is preserved.

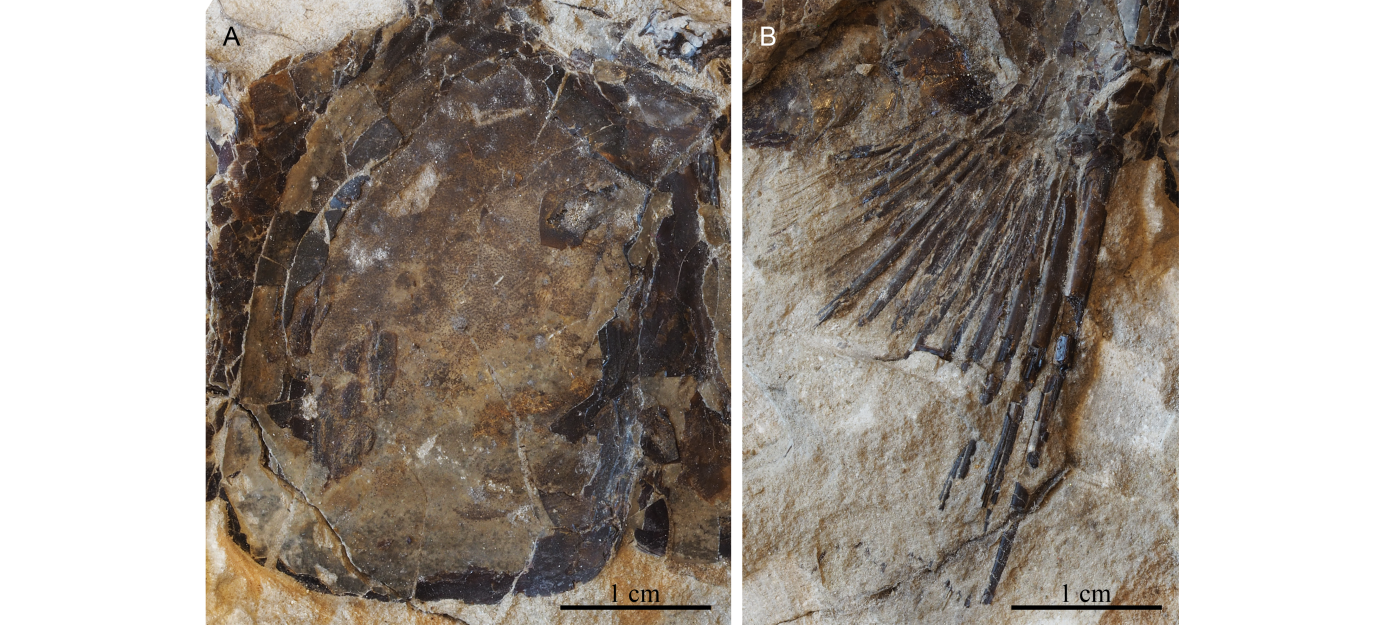

31The preopercle has two well-developed limbs forming a straight angle. The dorsal branch is a little shorter but also much broader than the ventral branch. Some traces of the preopercular sensory canal are present on the preopercle. A small part of the interopercle is visible under the ventral branch of the preopercle. The opercle is greatly hypertrophied, more or less ovoid and deeper than long (Fig. 3A). The lower margins of the opercle and of the preopercle are located at the same level. There is no place for a subopercle. A broad plate-like suprapreopercle covers the anterior dorsal corner of the opercle. Some regions of the preopercle and of the opercle are ornamented with very small tubercles.

32Figure 3. Cabindachanos dartevellei gen. and sp. nov. Holotype MRAC RG 4629; (A) detail of the hypertrophied opercle; (B) detail of the right pectoral fine.

332. The girdles

34Fragments of two rather narrow posttemporals are preserved. The right one is located just above the opercle and the left one against the supraoccipital median crest. The other scapular bones are hidden by the scales. The pectoral fin contains 14 segmented rays (Fig. 3B). The first ray is pointed distally and the thirteen others branched.

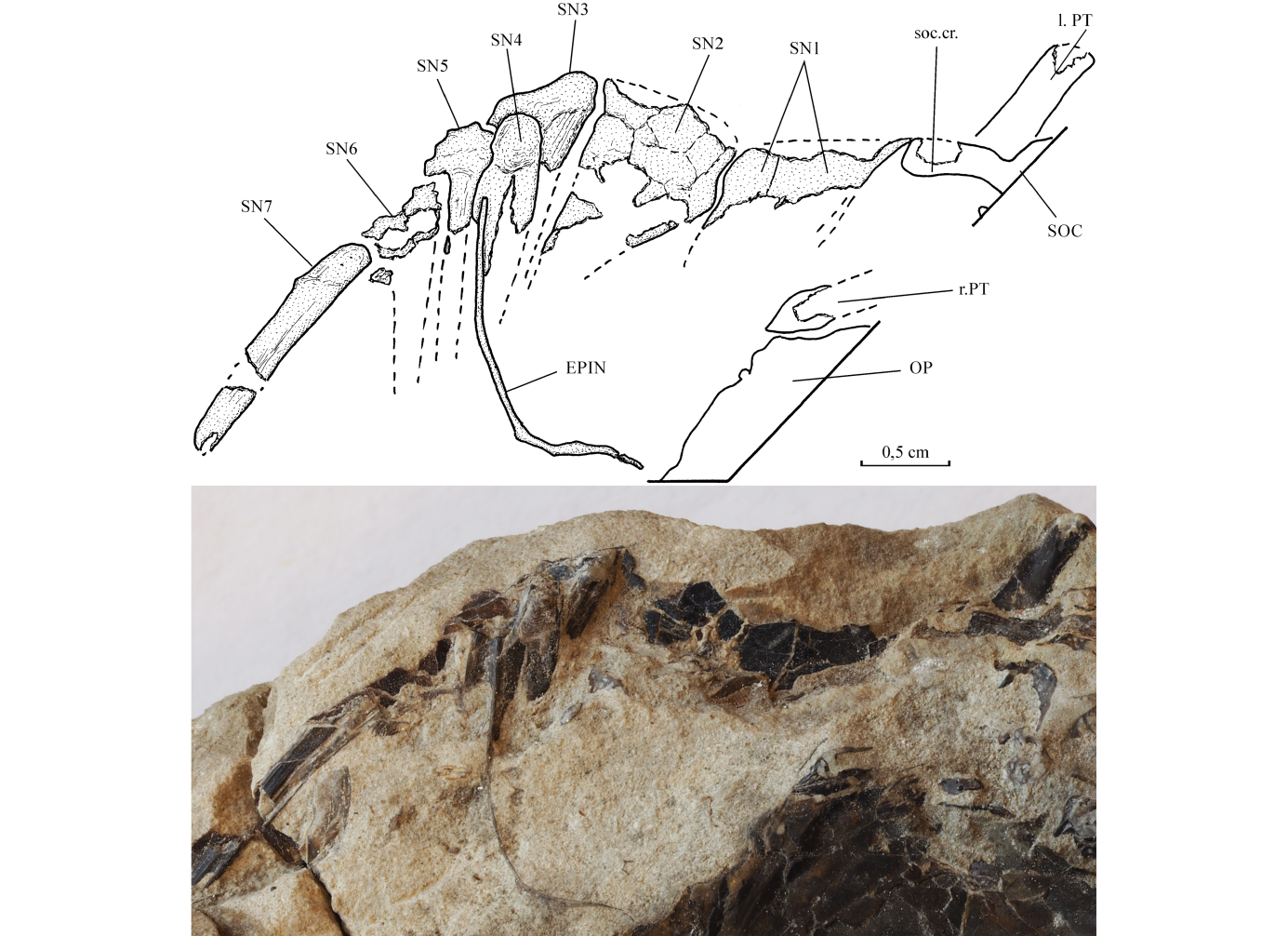

353. The axial skeleton (Fig. 4)

36The vertebrae are hidden under the scales. Fragments of a few anterior supraneurals are visible. The first two elements are extremely broadened. The third supraneural is broad but less so than the two preceding pieces. The following supraneurals are rod-like. The first visible supraneural is not especially close to the skull. It is perhaps not the first element of the supraneural series. One long, thin and curved epineural is visible below the first supraneurals.

37Figure 4. Cabindachanos dartevellei gen. and sp. nov. First supraneurals of holotype MRAC RG 4629.

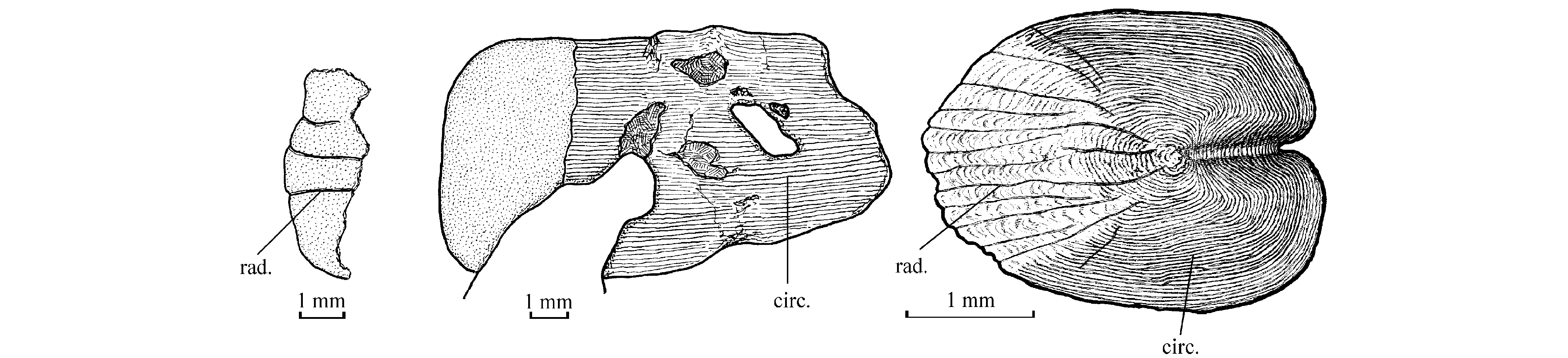

384. Squamation (Fig. 5)

39The scales are cycloid and longer than deep. The posterior region of the scales is thicker than more anteriorly and the posterior margin is smooth. Many very thin circuli are visible. They are horizontally oriented. Some fragmentary scales exhibit a few radii in the anterior region.

40Figure 5. Scales ofCabindachanos dartevellei gen. and sp. nov., from the abdominal region of holotype MRAC RG 4629 (left: fragment with radii, middle: a more or less complete scale) and of Chanos chanos (Forskål, 1775), from sample IRSNB IG 5606, Reg. 1470, standard fish length: 120 mm (right).

6. Discussion

6.1. Cabindachanos dartevellei gen. and sp. nov. within Teleostei

41Cabindachanos dartevellei gen. and sp. nov. exhibits a few features allowing to determine precisely its relationships within Teleostei. (1) The pelvic girdle is located in the abdominal region. (2) The scales are cycloid. (3) The skull is lateroparietal. (4) The lower jaw is deep, with the dentary forming a well-marked coronoid process. (5) The articulation between the quadrate and the mandible is positioned before the orbit. (6) The preopercle has a very broad dorsal limb and a long and rather narrow ventral limb. (7) The opercle is more or less ovoid and greatly hypertrophied. (8) There is a large plate-like suprapreopercle. (9) The first supraneurals are enlarged.

42Characters (1) and (2) indicate that C. dartevellei is a rather primitive teleost fish. On the other hand, the combination of characters (3) to (9) only occurs in Chanidae (Poyato-Ariza, 1996a; Grande & Poyato-Ariza, 1999; Poyato-Ariza et al., 2010). The placement of C. dartevellei in this gonorynchiform family is thus fully justified.

6.2. Cabindachanos dartevellei gen. and sp. nov., a valid genus

43In all the fossil and recent Chanidae, the opercle is hypertrophied but it does not reach ventrally the level of the lower margin of the preopercle. The subopercle is always present, even in those species with a relatively gigantic opercle, such as Rubiesichthys gregalis Wenz, 1984 from the Berriasian-Valanginian (early Early Cretaceous) of Spain (Poyato-Ariza, 1996b, fig. 2) or Nanaichthys longipinnus Amaral & Brito, 2012 from the Aptian (late Early Cretaceous) of Brazil (Amaral & Brito, 2012, fig. 4 A, B, C). Both species still retain a small subopercle.

44No other member of the family has such an enormous opercle as in the new chanid fish from Landana and none of them has completely lost the subopercle. These two characters justify the peculiar generic status of Cabindachanos dartevellei.

6.3. Cabindachanos dartevellei gen. and sp. nov. and the African fossil Chanidae

45Two fossil species of Chanidae have been described from Africa until now, Parachanos aethiopicus (Weiler, 1922) and Dastilbe batai Gayet, 1989, both from the marine-brackish Aptian-Albian (Lower Cretaceous) deposits of Gabon and Equatorial Guinea (Weiler, 1922; Arambourg & Schneegans, 1935; Casier & Taverne, 1971; Taverne, 1974; Gayet, 1989; Fara et al., 2007, 2010). However, D. batai is known by only one specimen with a very badly preserved skull. Some authors regard this species as a junior synonym of Dastilbe crandalli Jordan, 1910 from the Aptian of Brazil (Davis & Martill, 1999). Others consider that “it is difficult to [give] any precise taxonomic identification” to this sample (Brito & Amaral, 2008, p. 279).

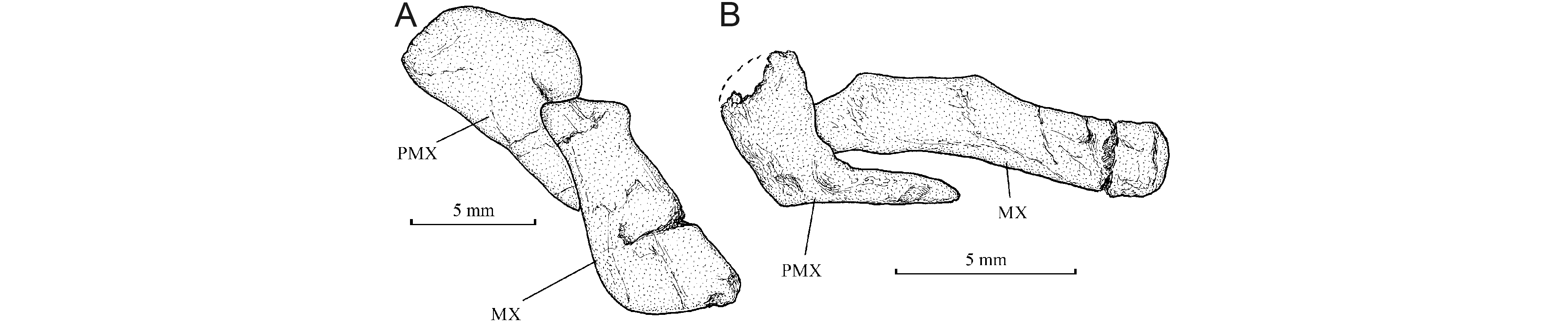

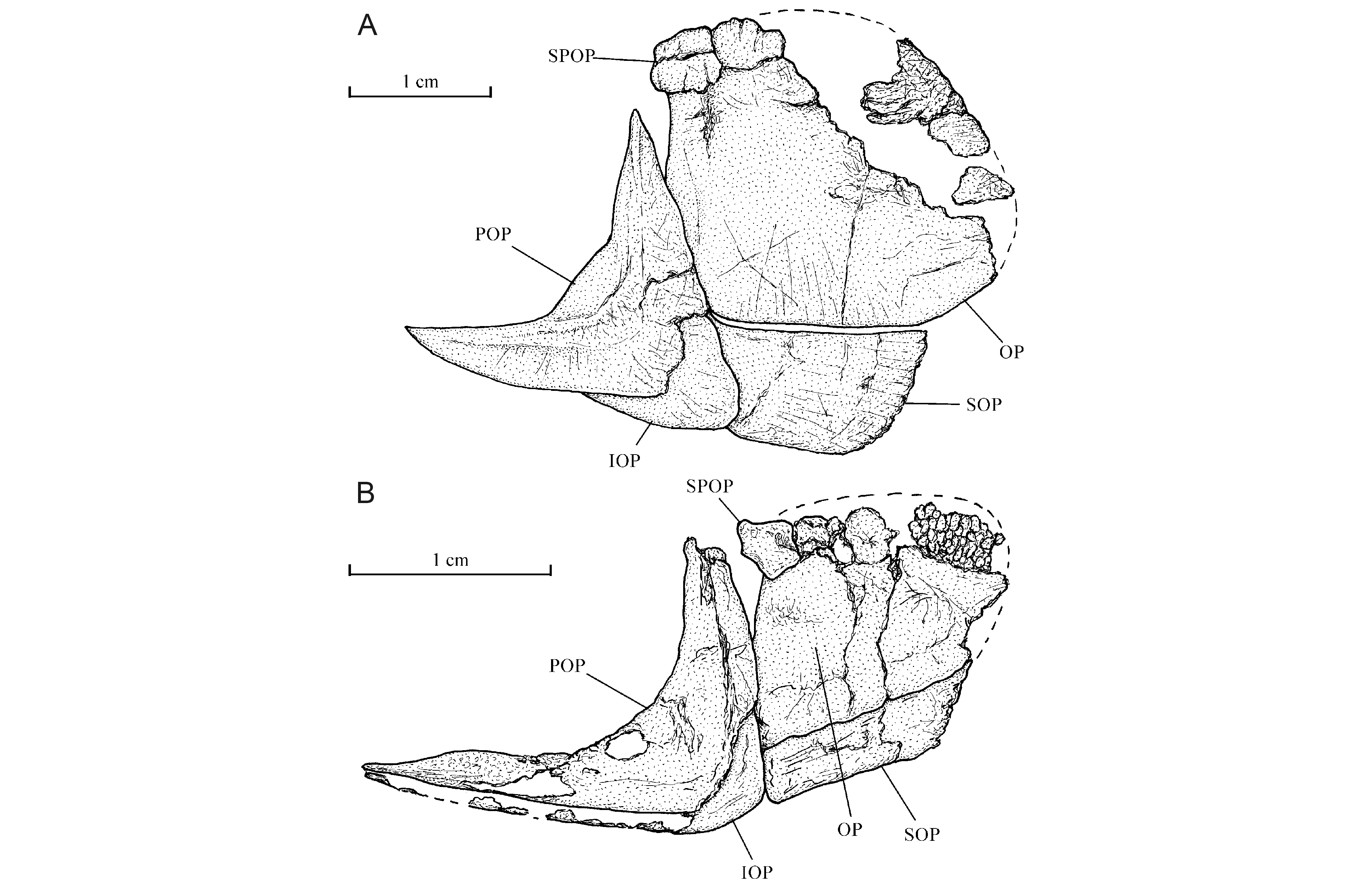

46Parachanos Arambourg & Schneegans, 1935 and Dastilbe Jordan, 1910 are two closely allied fossil chanid genera. They differ by only a few characters. The supraoccipital of Parachanos is devoid of a median posterior crest, while a small crest is present in Dastilbe (Fig. 6; Taverne, 1974, fig. 1; Dietze, 2007, fig. 3). The maxilla of Parachanos is short and obliquely oriented; the maxilla is longer and more horizontally positioned in Dastilbe (Fig. 7; Poyato-Ariza, 1996a, figs 7, 9; Poyato-Ariza et al., 2010, fig. 7.6). The subopercle of Parachanos is much larger than that of Dastilbe (Fig. 8). In the caudal skeleton of Parachanos, both the first preural (PU1) and the first ural (U1) vertebrae bear a reduced neural spine (Taverne, 1974, fig. 3; Poyato-Ariza, 1996a, fig. 17; Taverne & Capasso, 2017, fig. 13), as in the archaic chanid species Aethalionopsis robustus (Traquair, 1911) from the Upper Barremian of Belgium (Taverne, 1981, fig. 8; Taverne & Capasso, 2017, fig. 11). The reduced neural spine on PU1 is retained but that on U1 is lost in Dastilbe (Blum, 1991a, figs p. 279; Poyato-Ariza, 1996a, fig. 16; Dietze, 2007, fig. 10 A, B; Taverne & Capasso, 2017, fig. 14).

47Both Parachanosand Dastilbe possess a well-developed subopercle and, thus, differ from Cabindachanos.

48Figure 6. Skull roofs of (A) Dastilbe elongatus Da Silva Santos, 1947, sample CLC S-182 from the Aptian (Lower Cretaceous) deposits of Ceara, Brazil (left lateral view) and of (B) Parachanos aethiopicus (Weiler, 1922), cotype MNHN GAB 2 from the Aptian-Albian deposits of Cocobeach, Gabon (dorsal view).

49Figure 7. Upper jaws of (A) Parachanos aethiopicus (Weiler, 1922), cotype MNHN GAB 1 and of (B) Dastilbe elongatus Da Silva Santos, 1947, sample CLC S-182.

50Figure 8. Opercular regions of (A) Parachanos aethiopicus (Weiler, 1922), cotype MNHN GAB 1 and of (B) Dastilbe elongatus Da Silva Santos, 1947, sample CLC S-182. Both species have a well-developed subopercle.

6.4. Cabindachanos dartevellei gen. and sp. nov. within Chanidae

51Chanidae are subdivided into two subfamilies, the Chaninae, with the genera Chanos Lacépède, 1803, Caeus Costa, 1857, Tharrhias Jordan & Branner, 1908, Dastilbe, Parachanos and Aethalionopsis Gaudant, 1966, and the Rubiesichthyinae, with the genera Rubiesichthys Wenz, 1984, Gordichthys Poyato-Ariza, 1994 and Nanaichthys Amaral & Brito, 2012 (Poyato-Ariza, 1996a; Grande & Poyato-Ariza, 1999; Poyato-Ariza et al., 2010; Amaral & Brito, 2012). Prochanos Bassani, 1879, from the Upper Cretaceous of Croatia, sometimes is referred to the Chanidae (Poyato-Ariza, 1996a, p. 43) but is poorly known (Bassani, 1882, p. 217–219, pl. 13, pl. 14, fig.1, pl. 15) and seems to be a synonym of Chanos (Taverne & Capasso, 2017, p. 13).

52In Rubiesichthyinae, the two branches of the preopercle form an acute angle (Poyato-Ariza, 1994, fig. 3, 1996b, fig. 2; Amaral & Brito, 2012, fig. 4 A, B, C). That is not the case in Chaninae. Cabindachanos has the two branches of the preopercle forming a straight angle and, thus, belongs to the Chaninae.

53Within Chaninae, Cabindachanos shares one specialized character with Chanosand Tharrhias, the two members of the tribe Chanini. These three genera exhibit a strongly developed posterior median crest on the supraoccipital (Rabor, 1938, fig. 1; Taverne, 1981; fig. 11; Blum, 1991b, fig. p. 287; Poyato-Ariza, 1996a, fig. 14 B, 1996c, fig. 4). Such a crest is absent in Caeus, Parachanos and Aethalionopsis and weakly developed in Dastilbe (Fig. 6; Taverne, 1974, fig. 1, 1981, fig. 3; Dietze, 2007, fig. 3; Taverne & Capasso, 2017, fig. 4).

54Within Chanini, Cabindachanos seems closer to Chanos than to Tharrhias. The first two genera share at least one specialized character absent in the third genus. The parietals of the African chanid are reduced and broader than long. In Chanos, the parietals also are reduced and they form a tubular ossification surrounding the extrascapular sensory commissure (Poyato-Ariza, 1996a, p. 16, character 7[2]; Grande & Poyato-Ariza, 1999, p. 209, character 12[2], 2010, fig. 1.1 A). Tharrhias exhibits rather large parietals (Blum, 1991b, fig. p. 287 left; Poyato-Ariza, 1996c, fig. 4), representing a more primitive state.

7. Acknowledgments

55We greatly thank M. Stéphane Hanot, from the Royal Museum for Central Africa (Tervuren), and M. Adriano Vandersypen and M. Nathan Vallée Gillette, from the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences (Brussels), for their technical help. We are grateful to Dr. Jim Tyler and Dr. Francisco José Poyato-Ariza who commented on our manuscript.

56This research was supported by the Federal Science Policy Office of Belgium (BELSPO project BR/121/A3/PalEurAfrica).

8. References

57Amaral, C.R.L. & Brito, P.M., 2012. A new Chanidae (Ostariophysi: Gonorynchiformes) from the Cretaceous of Brazil with affinities to Laurasian gonorynchiforms from Spain. Plos One, 7/5, e37247, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0037247

58Arambourg, C. & Schneegans, D., 1935. Poissons fossiles du bassin sédimentaire du Gabon. Annales de Paléontologie, 24, 139–160.

59Bassani, F., 1882. Descrizione dei pesci fossili di Lesina accompagnata da appunti su alcune altre ittiofaune Cretacee (Pietraroia, Voirons, Comen, Grodischtz, Crespano, Tolfa, Hakel, Sahel-Alma e Vestfalia. Denkschriften der kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Mathematisch-naturwissenschaftliche Classe, Wien, 45/2, 195–288.

60Blum, S., 1991a. Dastilbe Jordan, 1910. In Maisey, J.G. (ed.), Santana fossils: An illustrated atlas. T.F.H. Publications Inc., Neptune City (U.S.A.), 274–283.

61Blum, S., 1991b. Tharrhias Jordan and Branner, 1908. In Maisey, J.G. (ed.), Santana fossils: An illustrated atlas. T.F.H. Publications Inc., Neptune City (U.S.A.), 286–296.

62Brito, P.M. & Amaral, C.R.L., 2008. An overview of the specific problem of Dastilbe Jordan, 1910 (Gonorynchiformes: Chanidae) from the Lower Cretaceous of western Gondwana. In Arratia, G., Schultze, H.-P. & Wilson, M.V.H. (eds), Mesozoic Fishes 4 – Homology and Phylogeny. Verlag Dr. F. Pfeil, München, 279–294.

63Casier, E. & Taverne, L., 1971. Note préliminaire sur le matériel paléoichthyologique éocrétacique récolté par la Spanish Gulf Oil Company en Guinée Equatoriale et au Gabon. Revue de Zoologie et de Botanique Africaines, 83/1-2, 16–20.

64Dartevelle, E. & Casier, E., 1943. Les poissons fossiles du Bas-Congo et des régions voisines (première partie). Annales du Musée du Congo Belge. A. – Minéralogie, Géologie, Paléontologie, série 3, 2/1, 1–200.

65Dartevelle, E. & Casier, E., 1949. Les poissons fossiles du Bas-Congo et des régions voisines (deuxième partie). Annales du Musée du Congo Belge. A. – Minéralogie, Géologie, Paléontologie, série 3, 2/2, 201–256.

66Dartevelle, E. & Casier, E., 1959. Les poissons fossiles du Bas-Congo et des régions voisines (troisième partie). Annales du Musée du Congo Belge. A. – Minéralogie, Géologie, Paléontologie, série 3, 2/3, 257–568.

67Davis, S.P. & Martill, D.M., 1999. The gonorynchiform fish Dastilbe from the Lower Cretaceous of Brazil. Palaeontology, 42/4, 715–740. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-4983.00094

68De Putter, T., Bayon, G., Mees, F., Ruffet, G. & Smith, T., 2016. Cenozoic sedimentation history of the Congo Basin revisited. SGF-ASF "Source to sink" Conference, Rennes, France, 30 Nov - 2 Dec 2016. https://hal-bioemco.ccsd.cnrs.fr/GR-3T/insu-01406477v1, accessed 01/23/2019.

69Dietze, K., 2007. Redescription of Dastilbe crandalli (Chanidae, Euteleostei) from the Early Cretaceous Crato Formation of North-Eastern Brazil. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 27/1, 8–16. https://doi.org/10.1671/0272-4634(2007)27[8:RODCCE]2.0.CO;2

70Fara, E., Gayet, M. & Taverne, L. 2007. Les Gonorynchiformes fossiles: distribution et diversité. Cybium, 31/2, 125–132.

71Fara, E., Gayet, M. & Taverne, L. 2010. The fossil record of Gonorynchiformes. In Grande, T., Poyato-Ariza, F.J. & Diogo, R. (eds), Gonorynchiformes and Ostariophysan Relationships. Science Publishers, Enfield (NH), Series on Teleostean Fish Biology, 173–226.

72Gayet, M., 1989. Note préliminaire sur le matériel paléoichthyologique éocrétacique du Rio Benito (sud de Bata, Guinée Équatoriale). Bulletin du Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, Paris, 4e série, 11, section C, 1, 21–31.

73Grande, T. & Poyato-Ariza, F.J., 1999. Phylogenetic relationships of fossil and recent gonorynchiform fishes (Teleostei: Ostariophysi). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 125/2, 197–238. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1096-3642.1999.tb00591.x

74Grande, T. & Poyato-Ariza, F.J., 2010. Reassessment and comparative morphology of the gonorynchiform head skeleton. In Grande, T., Poyato-Ariza, F.J. & Diogo, R. (eds), Gonorynchiformes and Ostariophysan Relationships. Science Publishers, Enfield (NH), Series on Teleostean Fish Biology, 1–37.

75Poyato-Ariza, F.J., 1994. A new Early Cretaceous gonorynchiform fish (Teleostei: Ostariophysi) from Las Hoyas (Cuence, Spain). Occasional Papers of the Museum of Natural History, University of Kansas, Lawrence, 164, 1–37.

76Poyato-Ariza, F.J., 1996a. A revision of the ostariophysan fish family Chanidae, with special reference to the Mesozoic forms. PalaeoIchthyologica, 6, 1–52.

77Poyato-Ariza, F.J., 1996b. A revision of Rubiesichthys gregalis Wenz 1984 (Ostariophysi, Gonorynchiformes) from the Early Cretaceous of Spain. In Arratia, G. & Viohl, G. (eds), Mesozoic Fishes – Systematics and Paleoecology. Verlag Dr. F. Pfeil, München, 319–328.

78Poyato-Ariza, F.J., 1996c. The phylogenetic relationships of Rubiesichthys gregalis and Gordichthys conquensis (Ostariophysi, Chanidae) from the Early Cretaceous of Spain. In Arratia, G. & Viohl, G. (eds), Mesozoic Fishes – Systematics and Paleoecology. Verlag Dr. F. Pfeil, München, 329–348.

79Poyato-Ariza, F.J., Grande, T. & Diogo, R., 2010. Gonorynchiform interrelationships: historic overview, analysis, and revised systematics of the group. In Grande, T., Poyato-Ariza, F.J. & Diogo, R. (eds), Gonorynchiformes and Ostariophysan Relationships. Science Publishers, Enfield (NH), Series on Teleostean Fish Biology, 227–337.

80Rabor, D.S., 1938. Studies on the anatomy of the bañgos, Chanos chanos (Forskål). I. The skeletal system. The Philippine Journal of Science, 67/4, 351–377.

81Solé, F., Noiret, C., Desmares, D., Adnet, S., Taverne, L., De Putter, L., Mees, F., Yans, J., Steeman, T., Louwye, S., Folie, A., Stevens N.J., Gunnell, G.F., Baudet, D., Kitambala Yaya, N. & Smith, T., in press. Reassessment of historical sections from the Paleogene marine margin of the Congo Basin reveals an almost complete absence of Danian deposits. Geoscience Frontiers. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gsf.2018.06.002

82Taverne, L., 1974. Parachanos Arambourg et Schneegans (Pisces Gonorhynchiformes) du Crétacé inférieur du Gabon et de Guinée Equatoriale et l’origine des Téléostéens Ostariophysi. Revue de Zoologie Africaine, 88/3, 683–688.

83Taverne, L., 1981. Ostéologie et position systématique d’Aethalionopsis robustus (Pisces, Teleostei) du Crétacé inférieur de Belgique et considérations sur les affinités des Gonorhynchiformes. Académie Royale de Belgique, Bulletin de la Classe des Sciences, 5e série, 67/12, 958–982.

84Taverne, L. & Capasso, L., 2017. Osteology and relationships of Caeus (“Chanos”) leopoldi (Teleostei, Gonorynchiformes, Chanidae) from the marine Albian (Early Cretaceous) of Pietraroja (Campania, southern Italy). Bollettino dem Museo Civico di Storia Naturale di Verona, Geologia Paleontologia Preistoria, 41, 3–20.

85Weiler, W., 1922. Die Fischreste aus den bituminösen Schiefern von Ibando bei Bata (Spanish Guinea). Paläontologische Zeitschrift, 5/2, 148–160. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03041550

86Manuscript received 05.06.2018, accepted in revised form 19.12.2018, available on line 23.01.2019.