- Accueil

- Volume 27 (2024)

- number 3-4 - Devonian lithostratigraphy of Belgium

- Upper Devonian lithostratigraphy of Belgium

Visualisation(s): 2975 (42 ULiège)

Téléchargement(s): 829 (31 ULiège)

Upper Devonian lithostratigraphy of Belgium

Abstract

The lithostratigraphic scale of Belgium, which is the cradle of several global Devonian stages, has been revised after completion of the update of the Geological Map of Wallonia (Carte géologique de Wallonie) at a scale of 1/25,000 and recent stratigraphic and sedimentological research. As a result, 100 lithostratigraphic units (groups, formations, members, facies, horizons) for the Upper Devonian Series have been re-defined. Whereas most of the units discussed in this overview are traditional divisions of the Belgian lithostratigraphic scale, this update includes revisions to their definitions, boundaries, and ages. New terms have been introduced essentially for notable horizons and facies. Additionally, some previously described formations have been reclassified as members as they are difficult to distinguish and separate on geological maps. The Frasnian lithostratigraphic units reflect the development of mixed argillaceous-carbonate deposits during the major transgressions that culminated at the end of the stage. This was followed by the gradual emergence of littoral siliciclastic facies that took place during the Famennian regression. Re-installation of carbonate deposits was recorded during the latest Famennian (Strunian transgression), heralding the lower Carboniferous carbonate succession to come. Reefs occur in the Frasnian (buildups, mud mounds, biostromes) and their presence in the middle Famennian is remarkable.

Table des matières

1. Introduction

1Establishing the lithostratigraphic scale of Belgium is a lengthy process dating back to the first half of the 19th century, when Dumont (1832) and Davreux (1833) published fundamental memoirs on the geology of the province of Liège. They were followed by several generations of geologists and palaeontologists, including Gosselet (1860, 1880a, 1888), Dewalque (1868), Mourlon (1875a, 1880) and Dupont (1881, 1882), to name but a few pioneers, who set out to name, date and correlate sedimentary successions. The first geological maps of the Belgian territory were published by d’Omalius d’Halloy (1822) and, above all, Dumont (1856). The almost complete geological mapping of the country was conducted in 1878–1885 and 1890–1919 (e.g. Renier, 1930; Boulvain, 1993a), and resulted in a detailed stratigraphic framework (Conseil de Direction de la Carte, 1892, 1896, 1900, 1909; Conseil géologique, 1929).

2Very early on, geologists have paid considerable attention to the Upper Devonian of southern Belgium because of its wide variety of building, industrial and ornamental stones, in particular the worldwide famous black and red limestones (referred to as ‘marbles’ in Belgian literature, i.e. compact limestones capable of being polished) (e.g. Groessens, 1981; Tourneur, 2020). Southern Belgium played a significant role in the development of Upper Devonian stratigraphy in the late 19th century. This is due to the high quality and abundance of outcrops, as well as the rich fossil content found particularly around the village of Frasnes-lez-Couvin and in the Famenne area. This contributed to the introduction of the Frasnian and Famennian stages by Gosselet (1879a) and Dumont (1857), respectively (see Coen-Aubert & Boulvain, 2006; Thorez et al., 2006). It is not possible to cite here all the papers that contributed to the knowledge of both stages from the lithostratigraphical viewpoint but, besides the few aforementioned pioneering works, major contributions of the 20th century are those of Maillieux (1914a, 1926, 1940a), Dumon (1929), Asselberghs (1936), Dumon et al. (1954), Lecompte (1960), Coen (1973, 1974), Coen-Aubert (1974a), and Boulvain et al. (1993a, 1999a) for the Frasnian, and Beugnies (1965), Bouckaert et al. (1968), Thorez et al. (1977), Dreesen et al. (1985), Conil et al. (1986), and Thorez & Dreesen (1986) for the Famennian.

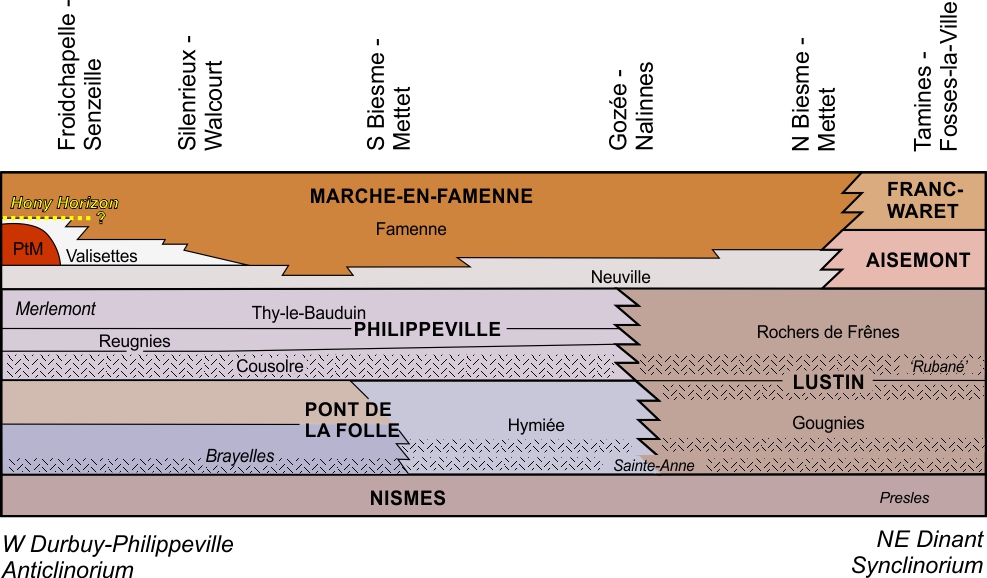

3A lithostratigraphic scheme aiming at defining Frasnian mappable units was published by Boulvain et al. (1993a) for the western part of the Durbuy–Philippeville Anticlinorium and enlarged some years later to the other tectonic units of southern Belgium (Boulvain et al., 1999a), and biostratigraphically calibrated by Bultynck et al. (2000) and Weddige (2000). In the meantime, several new units were introduced on the revised sheets of the Geological Map of Wallonia (Carte géologique de Wallonie) at a scale of 1/25,000 and detailed in the explanatory booklets, whereas the lithostratigraphy of the Famennian was left aside, with the exception of the overviews by Bultynck & Dejonghe (2002), Thorez et al. (2006) and Denayer et al. (2016). In Flanders, Laenen (2003) and Lagrou & Coen-Aubert (2017) proposed a stratigraphic framework for the Upper Devonian of the Campine Basin that is only known from borehole observations.

4The objectives of this paper are to update and supplement these previous works through the compilation of those produced by the mapping geologists and stratigraphers, who have dealt with the Upper Devonian over the last two decades.

2. Geological setting

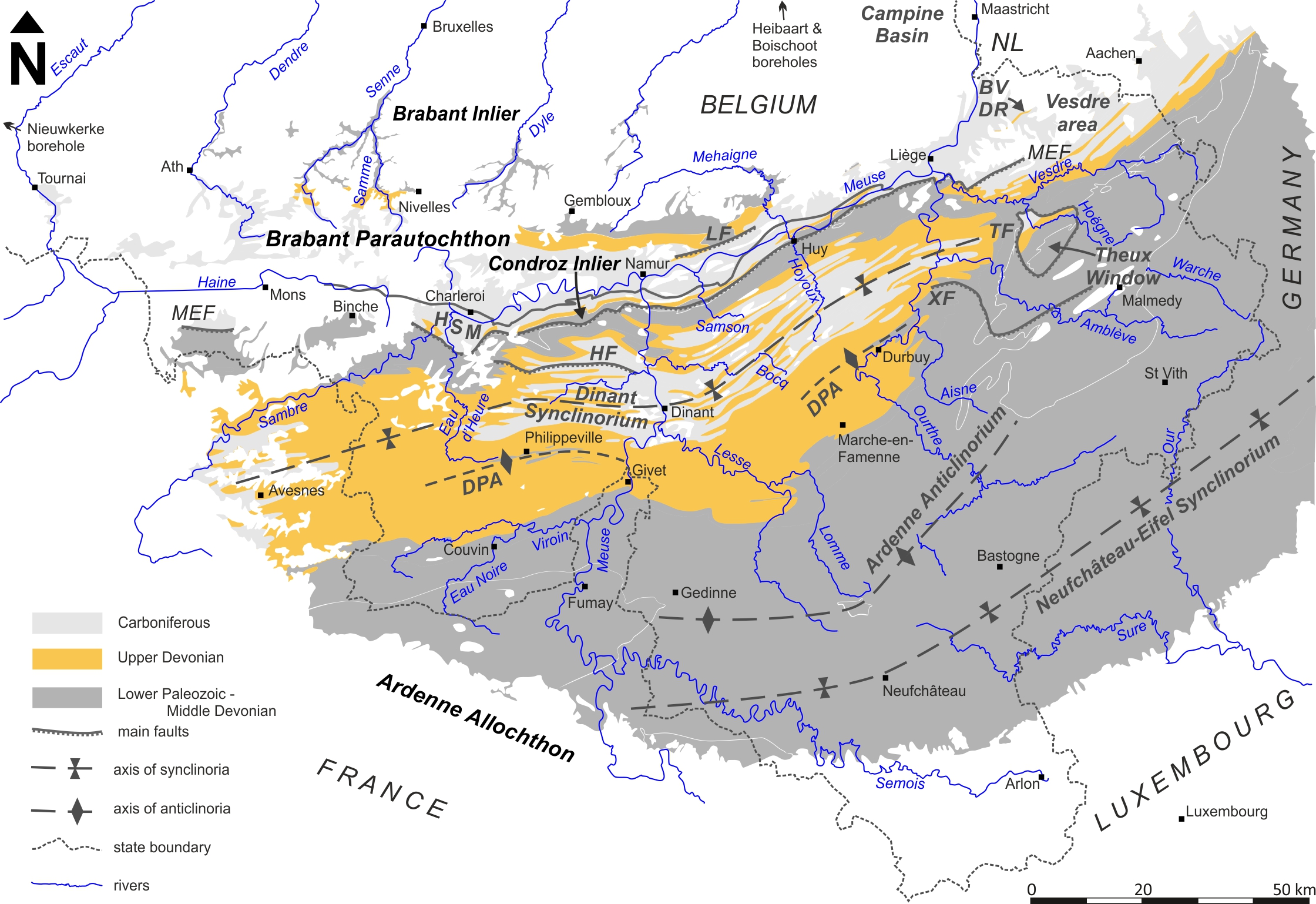

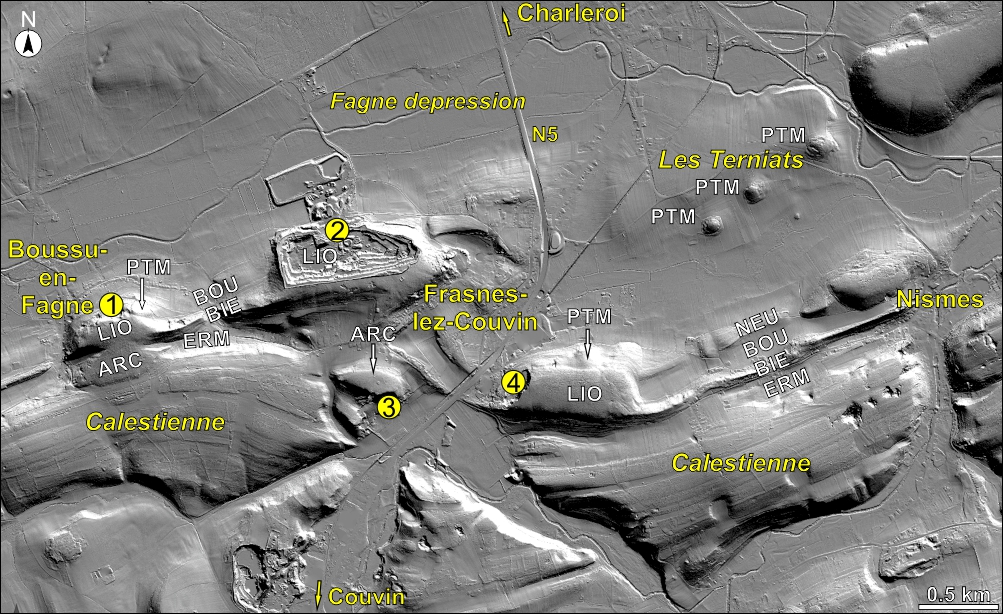

5The Upper Devonian covers large areas in the central part of southern Belgium, in contrast with rocks of Middle Devonian age that are restricted to narrow bands of outcrops (Fig. 1). The lower resistance of some upper Frasnian–lower Famennian predominantly argillaceous units to erosional processes have given rise to specific geomorphological landforms such as the Fagne–Famenne depression (e.g. Demoulin, 2018). This phenomenon is particularly evident in the Frasnes-lez-Couvin region, where the Frasnian limestone and nodular shale create pronounced topographic features in contrast to the shaly units that constitute the core of the Fagne depression or separate the more resistant units from one another (Fig. 2). Conversely, the core of the Dinant Synclinorium (Fig. 1), known as the Condroz, is characterised by a structurally controlled topography in which thick series of Famennian siliciclastics occupy the anticline axes contrary to the Carboniferous carbonates that crop out in the syncline axes (e.g. Poty, 1976). In the Ardenne Allochthon, Upper Devonian deposits are extensively encountered in the Dinant Synclinorium and in the Durbuy–Philippeville Anticlinorium (de Magnée, 1930, 1932; Barchy & Marion, 2008, see also Mottequin & Denayer, 2024). The Upper Devonian is also known, thanks to numerous outcrops and boreholes, from the Brabant Parautochthon and the Haine–Sambre–Meuse Overturned Thrust sheets (Belanger et al., 2012). Contemporaneous rocks crop out in the Theux Window (and Bolland borehole) and the Vesdre area (Fig. 1). North of the Brabant Inlier (Fig. 1), the Upper Devonian is only accessed by boreholes in the Campine Basin, whereas it sporadically crops out in the tectonic blocks of the Visé–Maastricht area, near the eastern end of the Brabant Inlier (Poty, 1991).

Figure 1. Simplified geological map of the Upper Devonian of central and southern Belgium and neighbouring countries (adapted from de Béthune, 1954), with indication of the main structural units, including the Caledonian inliers. Abbreviations: BVDR, Booze–Le Val-Dieu Ridge; DPA, Durbuy–Philippeville Anticlinorium; HSM, Haine–Sambre–Meuse Overturned Thrust sheets; NL, the Netherlands. Major faults: HF, Hanzinne Fault; LF, Landenne Fault; MEF, Midi–Eifel Thrust Fault; TF, Theux Fault; XF, Xhoris Fault.

Figure 2. LIDAR-derived image of the historical type area of the Frasnian Stage in southern Belgium (Namur province) with indication of the main sedimentary bodies and their influence on topography (from Service Public de Wallonie) (to be compared with the geological map of Marion & Barchy, 1999). Quarries are numbered: 1, disused Cimetière quarry; 2, active Nord quarry; 3, disused Arche quarry (stratotype of the Arche Member); 4, disused Lion quarry (stratotype of the Lion Member). Abbreviations: ARC, Arche Member; BIE, Bieumont Member; BOU, Boussu-en-Fagne Member; ERM, Ermitage Member; LIO, Lion member; NEU, Neuville Member; PTM, Petit-Mont Member.

6The Frasnian succession displays strong lithological variations between the southern and south-eastern limbs (presence of carbonate buildups and mud mounds) of the Dinant Synclinorium and its northern limb, the Haine–Sambre–Meuse Overturned Thrust sheets, and the Vesdre area (e.g. Dumon et al., 1954; Boulvain et al., 1993a, 1999a). The Brabant Parautochthon is characterised by its distinct succession (e.g. Asselberghs, 1936; Boulvain et al., 1999a), which shares similarities with that of the Heibaart and Booischot boreholes in the Campine Basin (Lagrou & Coen-Aubert, 2017). The Frasnian recognised in the deep Tournai and Leuze boreholes (Coen-Aubert et al., 1981) is characterised by the great thickness of the encountered units of which the assignment to units known to the east of the Brabant Parautochthon is problematic. The sedimentological differences observed in the Frasnian succession of the Namur–Dinant Basin (see Mottequin & Denayer, 2024 for more information about this basin) are the result of its development in a ramp–platform context, with the shallower facies occurring in the northern part of the basin. This was influenced by multiple breaks of slope during time of deposition and was also controlled by a complex eustatic history with significant transgression pulses (Johnson et al., 1985; Da Silva & Boulvain, 2012).

7The Famennian of southern Belgium witnesses a large-scale regression (Thorez & Dreesen, 1986). Argillaceous sediments deposited during the early Famennian, with their maximal development recorded in the southern part of the Namur–Dinant Basin. During the middle–late Famennian, alluvial to offshore siliciclastic deposits were predominant in the basin, with subordinate carbonates developed essentially in the middle and latest Famennian (Thorez et al., 2006). The overall distribution of facies was controlled by synsedimentary block faulting (Thorez & Dreesen, 1986) starting in the Lower Devonian and culminating in the Carboniferous (Hance et al., 2001). The Famennian of the Campine Basin, which contains numerous stratigraphic gaps and lacks biostratigraphic data, was controlled by block faulting and regional irregularities of the basin palaeotopography (Laenen, 2003; Thorez et al., 2006).

3. Chronostratigraphy of the Upper Devonian

8The Upper Devonian consists of the Frasnian and Famennian stages, as confirmed at the 1981 meeting in Binghampton (USA) by the Subcommission on Devonian Stratigraphy (SDS) of the International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS) (Ziegler & Klapper, 1982); the latter officially approved the SDS proposal in 1985 (Bassett, 1985). The term Frasnien (Frasnian), clearly related to the système du calcaire de Frasne introduced by d’Omalius d’Halloy (1862, p. 514), was first used by Gosselet (1879a, p. 130, 133) in his description of the Maubeuge canton in northern France (see also Coen-Aubert & Boulvain, 2006). The term Famennien (Famennian) was introduced by Dumont (1857, legend of the Carte géologique de l’Europe) as the Faménien [sic] and corresponded to the lower part of the système condrusien that was proposed anteriorly (Dumont, 1848, p. 210) (see Thorez et al. (2006) for further information).

9In a footnote, Gosselet (1879b, p. 396) subdivided the Upper Devonian into two parts, in ascending order: the Frasnian including the zone à Rhynchonella cuboides and the zone à Cardium palmatum, and the Famennian in which he put together the schistes de Famenne, Psammites du Condros, and calcaires d’Etrœungt. On the southern limb of the Dinant Synclinorium, the zone à Rhynchonella cuboides sensu Gosselet (1879b) corresponds, in terms of current lithostratigraphic units (see section 7), to the Nismes, Moulin Liénaux, Grands Breux and Marche-en-Famenne (Neuville Member) formations whereas his zone à Cardium palmatum corresponds to the Matagne Facies of the latter lithostratigraphic unit. It is worthwhile to remind here that the position of the Givetian–Frasnian Boundary in Belgium was placed by Maillieux & Demanet (1929) at the base of the Fromelennes Formation, thus well below the current boundary (see Denayer et al., 2024 for further information). Gosselet (1880a, p. 108) restricted the Famennian to the faciès schisteux ou schistes de Famenne and to the faciès arénacé ou Psammites du Condros. Gosselet (1880a, p. 108–111) subdivided the Schistes de Famenne into four zones, which are in ascending order: the Schistes de Senzeilles à Rhynchonella Omaliusi, Schistes de Marienbourg à Rhynchonella Dumonti, Schistes de Sains à Rhynchonella letiensis, and Calcaire d’Etrœungt à Spirifer distans. Nowadays, the Schistes de Famenne would include only the two first ‘zones’ (Bultynck & Dejonghe, 2002; see section 7 for more details). Originally, the Frasnian–Famennian Boundary sensu Gosselet (1877a, 1880a) was placed at the contact between the schistes de Matagne à Cardium palmatum and the schistes de Famenne à Cyrthia Murchisoniana in the Charleroi–Vireux railway trench, south of the village of Senzeille. A sketch of this outcrop was published by Gosselet (1888) and complemented by Sartenaer (1960). Unfortunately, this famous section partially disappeared in 1976 when the N978 road was built. The preservation of the southern face of the trench was organised by the Belgian Geological Survey, but the Frasnian–Famennian Boundary was no longer visible in the preserved part (Casier & Bultynck, 2000). The Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences therefore undertook to dig two additional trenches exposing the missing part of the original succession in the late 1980s. Unfortunately, the three sections were illegally backfilled in 1993 (Bultynck & Martin, 1995; Casier & Bultynck, 2000). In 1995, a new trench was dug to restore the Senzeille section and the site was fenced off for protection (Casier & Bultynck, 2000). However, the Frasnian–Famennian Boundary is no longer exposed at the site of the original type locality and only the Lower Famennian succession outlined by Martin (1984) was still visible in 2003 (Mottequin, 2005a).

10In 1986, the ICS ratified the proposal of the SDS aiming to place the base of the Frasnian at the first occurrence of the conodont Ancyrodella rotundiloba (Klapper et al., 1987), that is at the base of the lower asymmetricus conodont Zone of Ziegler (1971) or within the lower falsiovalis conodont Zone of Ziegler & Sandberg (1990). The Global Stratotype Section and Point (GSSP) is located at the Puech de la Suque pass near Saint-Nazaire-de-Ladarez, south-west of the Montagne Noire (France, Hérault) (Klapper et al., 1987).

11The base of the Famennian coincides with that of the lower triangularis conodont Zone; the GSSP is located at Coumiac, near Cessenon in Montagne Noire (Klapper et al., 1993; House et al., 2000). Nevertheless, the GSSP does not correspond to the entry (first appearance datum (FAD)) of the conodont Palmatolepis triangularis; that is why Spalletta et al. (2017) renamed the basalmost Famennian conodont zone as the subperlobata Zone. Mouravieff (1974) and Streel et al. (1975) reported P. subperlobata in the former Senzeille railway section, but above the lowest occurrence of P. triangularis. Bultynck & Martin (1995) did not mention P. subperlobata in the lowermost Famennian exposed in the Senzeille sections dug by the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences, but they reported the species P. delicatula delicatula and P. protorhomboidea that are considered as characteristic of the subperlobata conodont Zone by Spalletta et al. (2017). Note that P. subperlobata was also cited in the Belgian Famennian notably by Bouckaert et al. (1965, 1974a), Streel et al. (1975), and Dusar & Dreesen (1984). In the absence of recent conodont investigation on the Belgian lowermost Famennian, it is currently more reasonable to use the biozonation of Ziegler & Sandberg (1990). The top of the Famennian is placed at the base of the overlying Tournaisian Stage (Carboniferous) whose GSSP is defined on the slope of La Serre Hill, near Cabrières in Montagne Noire, with the FAD of the conodont Siphonodella sulcata (Paproth et al., 1991). Although this limit has long been criticised, it remains valid pending further decisions by the Subcommission on Carboniferous Stratigraphy and the ICS (Aretz et al., 2020).

12The Strunian regional substage was first introduced by de Lapparent (1900, p. 860) to encompass the calcaire d’Œtrœungt of Gosselet (1857, p. 364, p. 367, footnote) in the Avesnois area (northern France) and in western Belgium, which is replaced further to the east by the Comblain-au-Pont Formation. Barrois (1913, p. 16) considered it as a distinct stage between the Famennian and the Tournaisian. However, in the classical Belgian literature, the Strunian has often been regarded as the lower part of the Tournaisian (e.g. sous-assise d’Étrœungt et de Comblain-au-Pont, Tn1a in Demanet, 1958).

13In the modern sense, the Strunian corresponds to the uppermost Famennian according to proposals by Streel et al. (1998) and Streel (2005) to subdivide the Famennian into four substages. As reminded by Denayer et al. (2021), the base of the Strunian is not yet formally defined but is generally correlated with that of the Bispathodus ultimus conodont Zone sensu Hartenfels & Becker (2018) (former upper expansa conodont zone). From the foraminifer viewpoint, its lower boundary corresponds to the first occurrence (FO) of Quasiendothyra kobeitusana (Conil & Lys, 1970). Conil et al. (1977) proposed to use the FO of the miospore Retispora lepidophyta as the base of the Strunian. Though its FO is well below that of the Etrœungt Formation—therefore in the upper Famennian (Streel et al., 2006; Marynowski et al., 2012)—its occurrence is very diagnostic for the Strunian substage.

14The substage definitions proposed by the SDS have not yet been ratified by the ICS (Becker et al., 2020), that is why we do not use a capital for indicating the geochronologic (e.g. late Frasnian) and chronostratigraphic (e.g. upper Frasnian) units (Owen, 2009).

4. Geochronology of the Late Devonian

15The Late Devonian extends from c. 378.9 Ma to c. 359.3 Ma and is subdivided into two ages: Frasnian (c. 378.9 Ma to c. 371.1 Ma) and Famennian (c. 371.1 Ma to c. 359.3 Ma) (Becker et al., 2020).

5. Biostratigraphy of the Upper Devonian

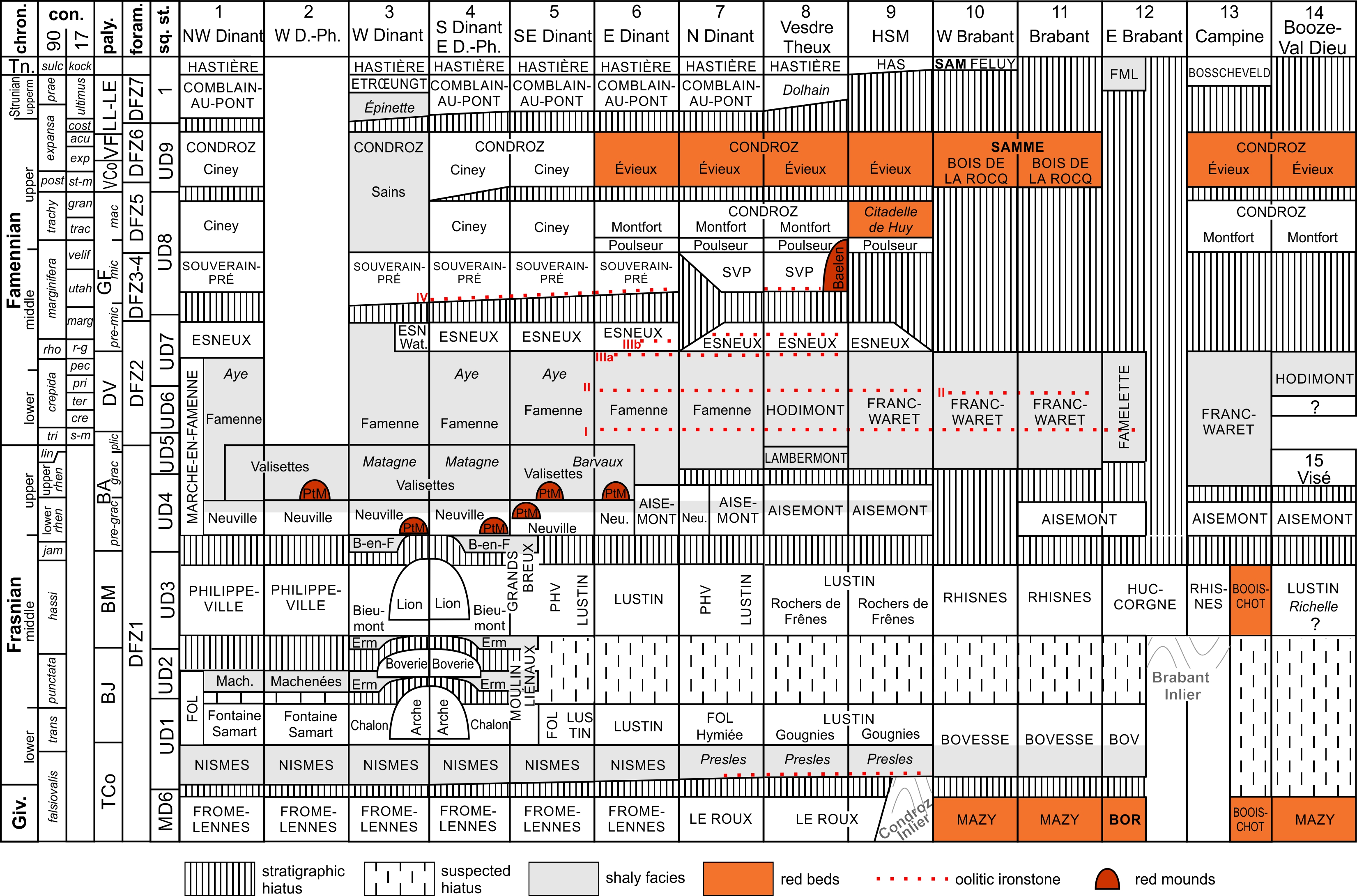

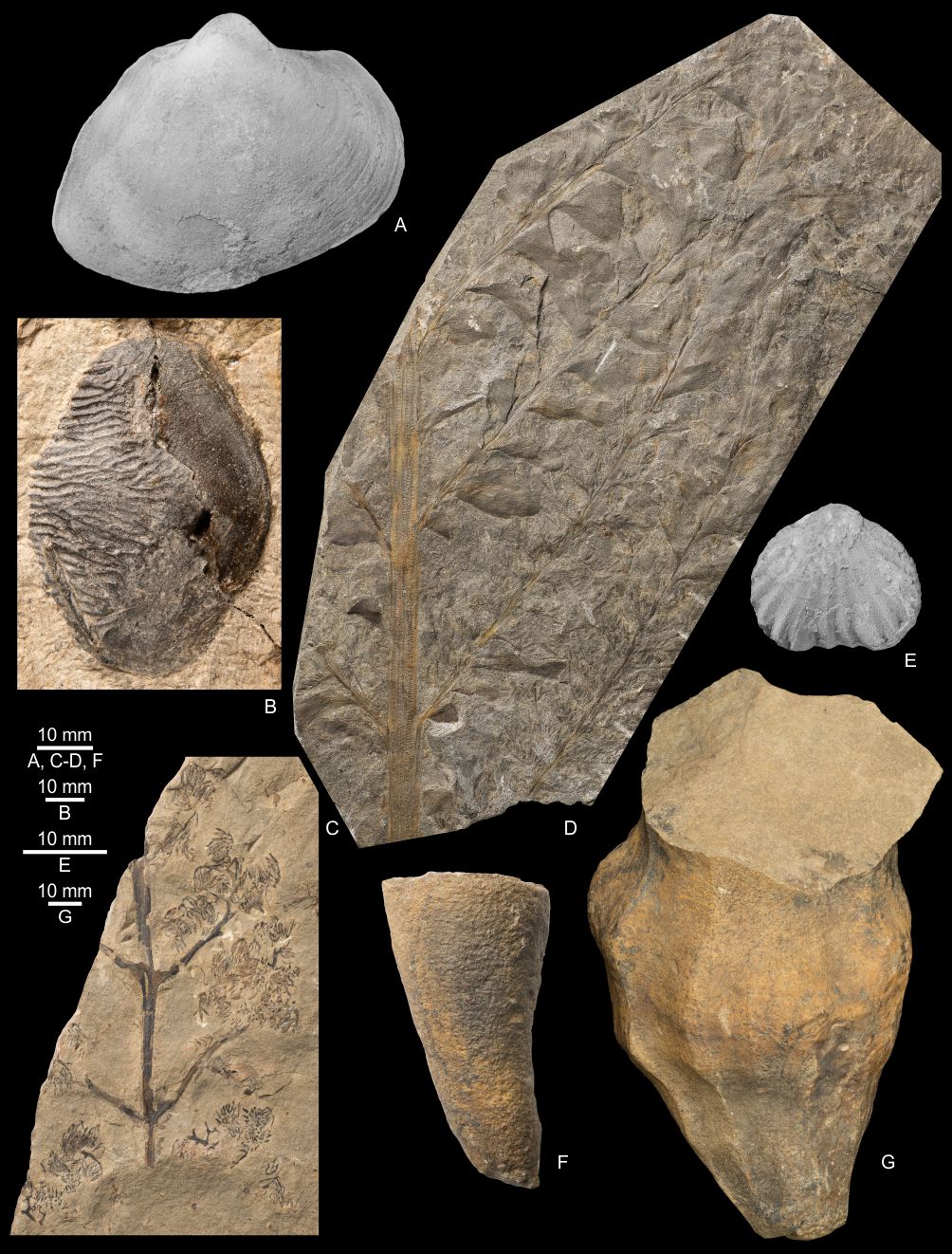

16The Upper Devonian strata of Belgium (Figs 3, 4), which include a large variety of carbonate and siliciclastic lithologies, yielded a large amount of stratigraphically useful macro- (brachiopods, corals) and microfossils (e.g. conodonts, foraminifers, palynomorphs).

Figure 3. Chronostratigraphic chart of the Upper Devonian strata of Belgium (origin of data: see main text); numbers 1–15 refer to geographical zones. Groups are in capital and bold letters, formations in capital letters, members in regular letters, remarkable horizons and facies in italics. Abbreviations (except conodonts): B.-en-F., Boussu-en-Fagne Member; BOR: Bois de Bordeaux Group; BOV, Bovesse Formation; chron., chronostratigraphy; con., conodont zones (90, see Ziegler & Sandberg, 1990; 17, see Spalletta et al., 2017); D.-Ph., Durbuy–Philippeville Anticlinorium; Erm., Ermitage Member; ESN, Esneux Formation; FML, Famelette Formation; FOL, Pont de la Folle Formation; foram., foraminifer zones; Giv., Givetian; HAS, Hastière Formation; HSM, Haine–Sambre–Meuse Overturned Thrust sheets; Mach., Machenées; Neu., Neuville Member; paly., palynozones (e.g. Streel, 2009; Streel et al., 2021); PHV, Philippeville Formation; PtM, Petit-Mont Member; sq. st., sequence stratigraphy; SAM, Samme Group; SVP, Souverain-Pré Formation; Tn., Tournaisian; upperm, uppermost; Wat.: Watissart Member. I–IV, oolitic ironstone horizons. Conodont abbreviations: acu, aculeatus; cost, costatus; cre, crepida; exp, gracilis expansa; gran, granulosus; kock, kockeli; jam, jamieae; lin, linguiformis; marg, marginifera marginifera; pec, glabra pectinata; post, postera; prae, praesulcata; pri, glabra prima; r–g, rhomboidea–gracilis gracilis; rhen, rhenana; rho, rhomboidea; s–m, subperlobata–minuta minuta; st–m, styriacus–gracilis manca; sulc, sulcata; ter, termini; trac and trachy, trachytera; trans, transitans; tri, triangularis; utah, marginifera utahensis; vel, velifer.

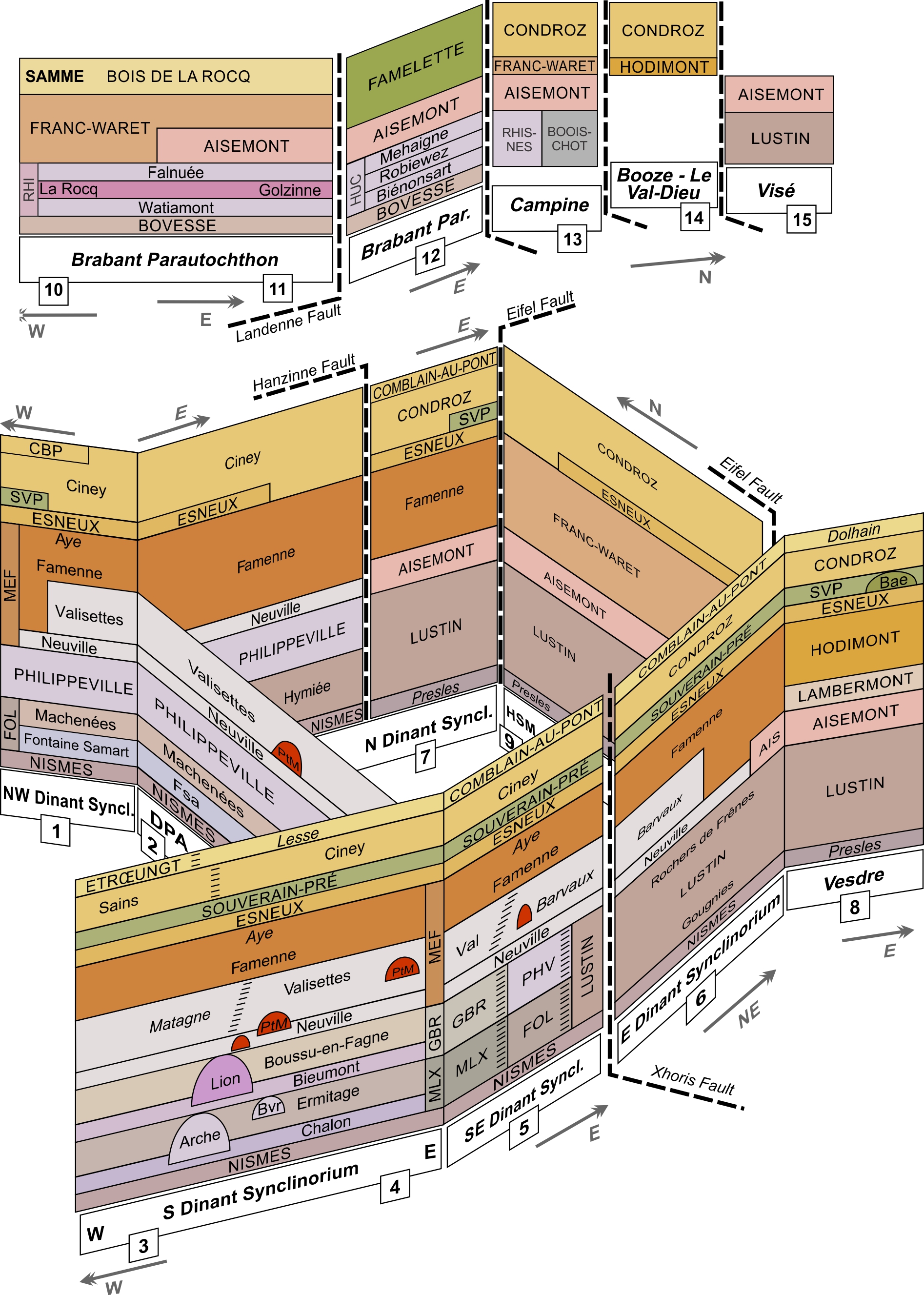

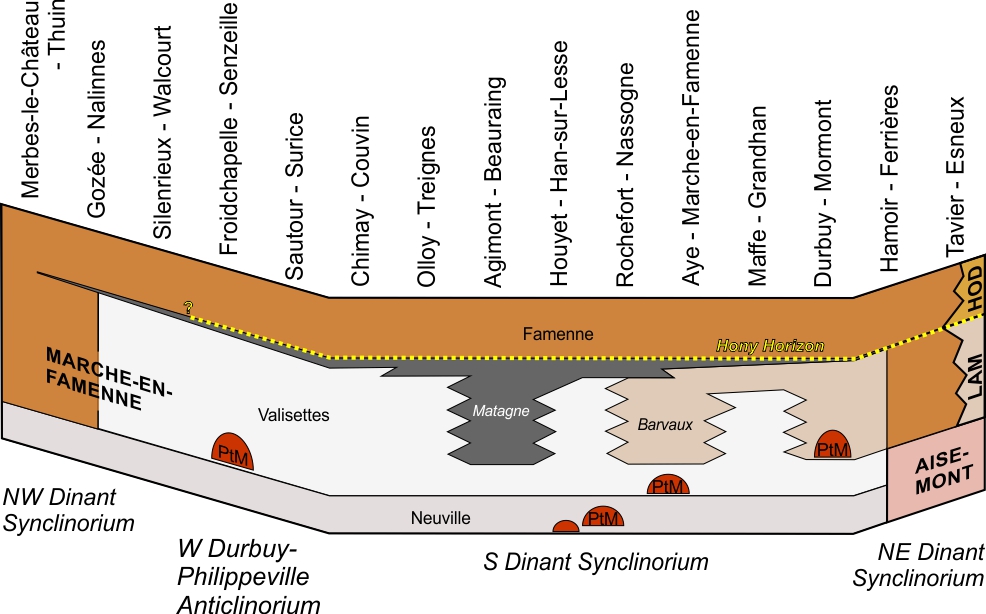

Figure 4. Schematic vertical and relationships of the Upper Devonian of Belgium. Formations are in capital letters, members are in regular letters, names in italics are remarkable horizons and facies. The stratigraphic hiatuses shown in Figure 3 are not represented here. Abbreviations: AIS, Aisemont Formation; Bae, Baelen; Bvr, Boverie Member; CBP, Comblain-au-Pont Formation; DPA, Durbuy–Philippeville Anticlinorium; FOL, Pont de la Folle Formation; Fsa; Fontaine Samart Member; GBR, Grands Breux Formation; HSM, Haine–Sambre–Meuse Overturned Thrust sheets; HUC, Huccorgne Formation; MEF, Marche-en-Famenne Formation; MLX, Moulin Liénaux Formation; Par., Parautochthon; PHV, Philippeville Formation; PtM, Petit-Mont Member; RHI, Rhisnes Formation; SVP, Souverain Pré Formation; Syncl., Synclinorium; Val, Valisettes Member.

5.1. Conodonts

17Research on conodonts of the Upper Devonian of Belgium started in the 1960s. Frasnian conodonts were notably studied by Mouravieff (1970, 1974, 1982), Coen (1973, 1974), Coen & Coen-Aubert (1974), Bultynck & Jacobs (1982), Vandelaer et al. (1989), Helsen & Bultynck (1992), Sandberg et al. (1992), and Bultynck et al. (1998). It appears that the standard conodont zonation of Ziegler & Sandberg (1990), mainly based on the key palmatolepid species, is difficult to recognise in the Namur–Dinant Basin due to the rarity of the ‘pelagic’ Palmatolepis representatives (Vandelaer et al., 1989, Dreesen & Thorez, 1994). Therefore, Coen (1999) continues to use Ziegler’s (1971) zonation cautiously. Gouwy & Bultynck (2000) revised the range of 85 conodont taxa in the Frasnian of southern Belgium.

18The Famennian conodont stratigraphy was explored in the pioneering works of Bouckaert et al. (1965, 1968) that were notably complemented by those of Thorez et al. (1977) and Dreesen & Houlleberghs (1980). Because of unsuitable facies, most of the pelagic markers are missing in the Belgian Famennian and the standard conodont zones are not recognised. Sandberg & Dreesen (1984) developed a parallel zonation, based on icriodontid genera widely distributed in neritic facies. The latter zonation, emended by Dreesen & Thorez (1980, 1994), Van Steenwinkel (1980, 1988), Dreesen et al. (1985, 1993), and Bultynck & Martin (1995), proves to be useful for regional and inter-regional correlations.

5.2. Brachiopods

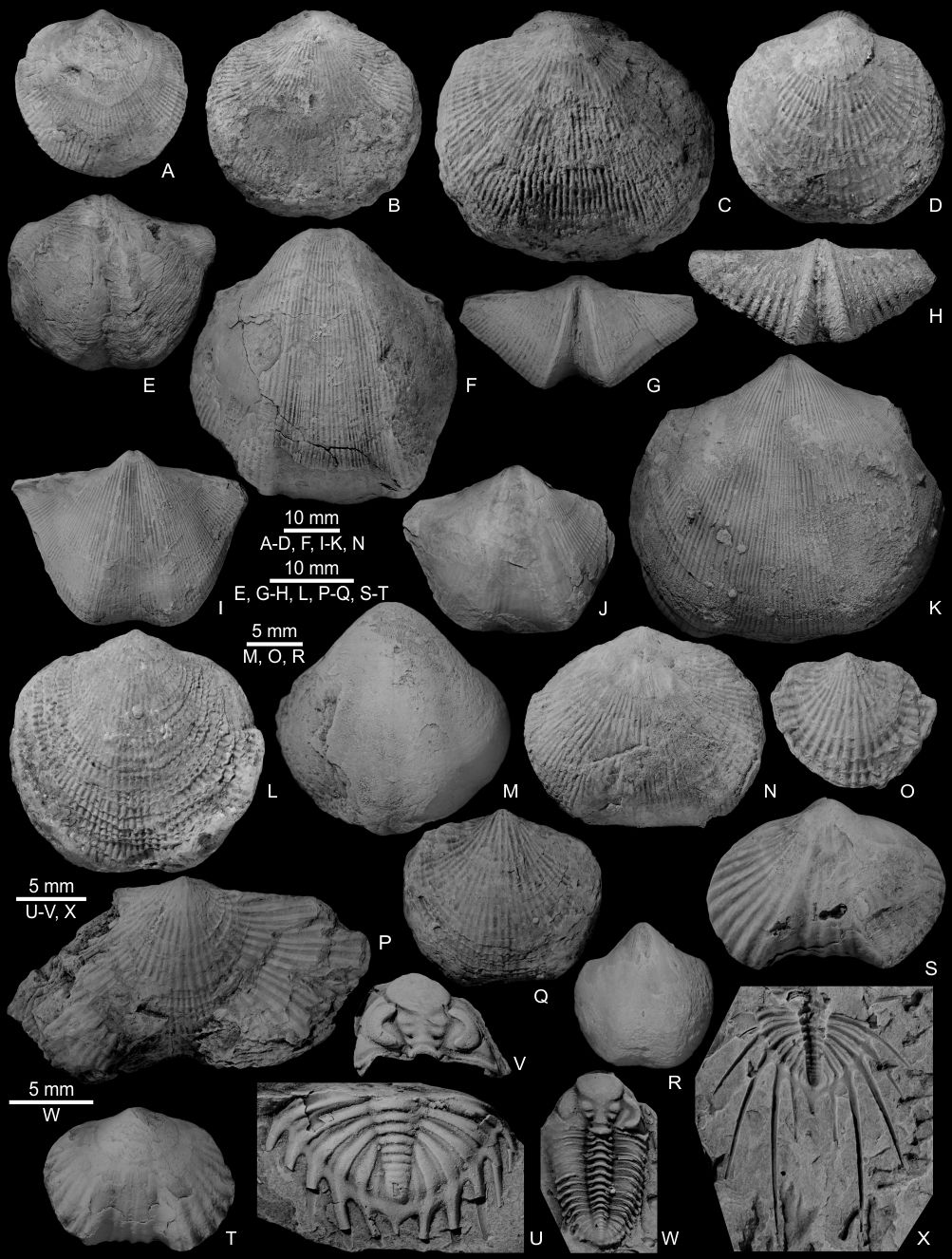

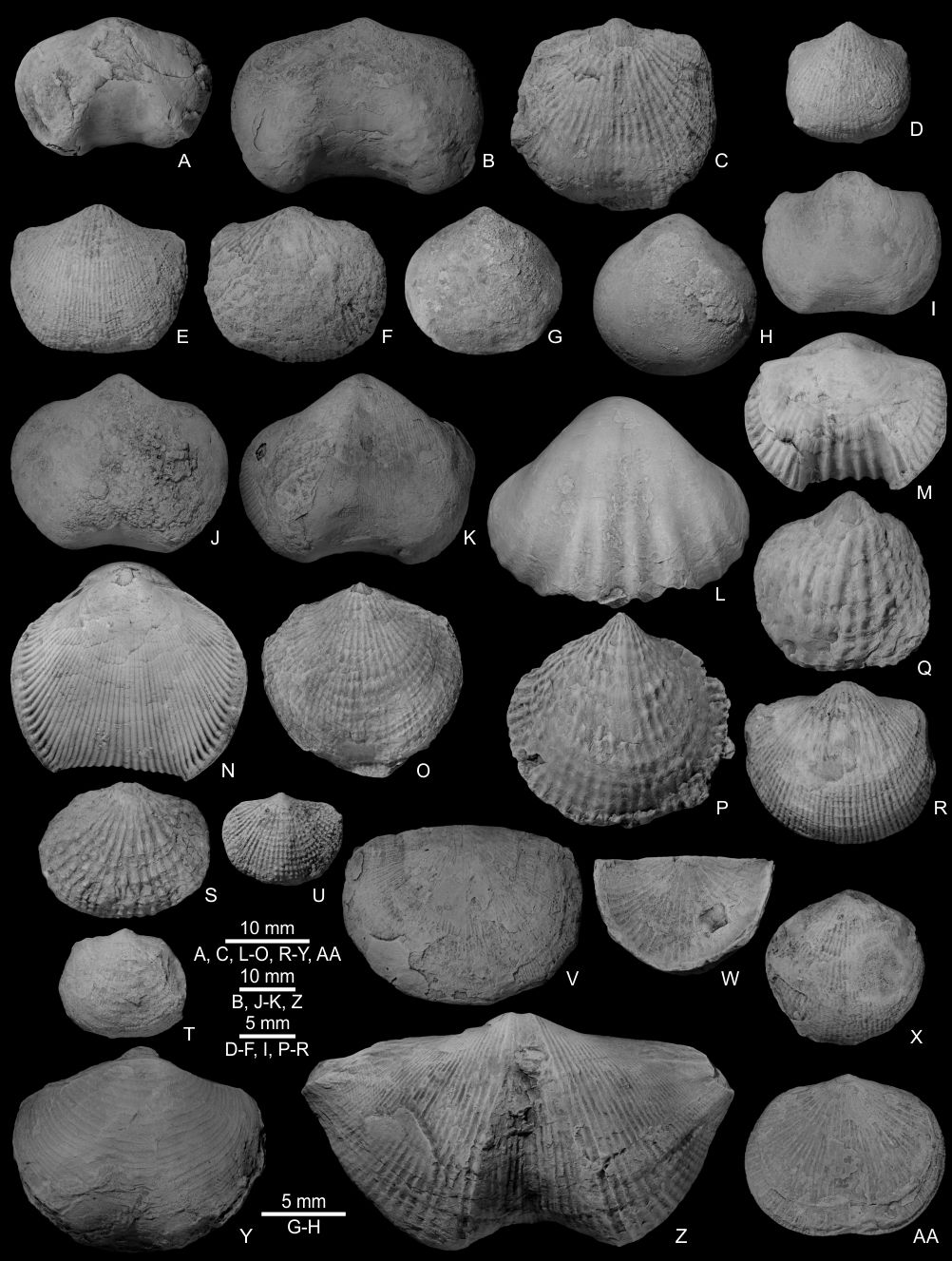

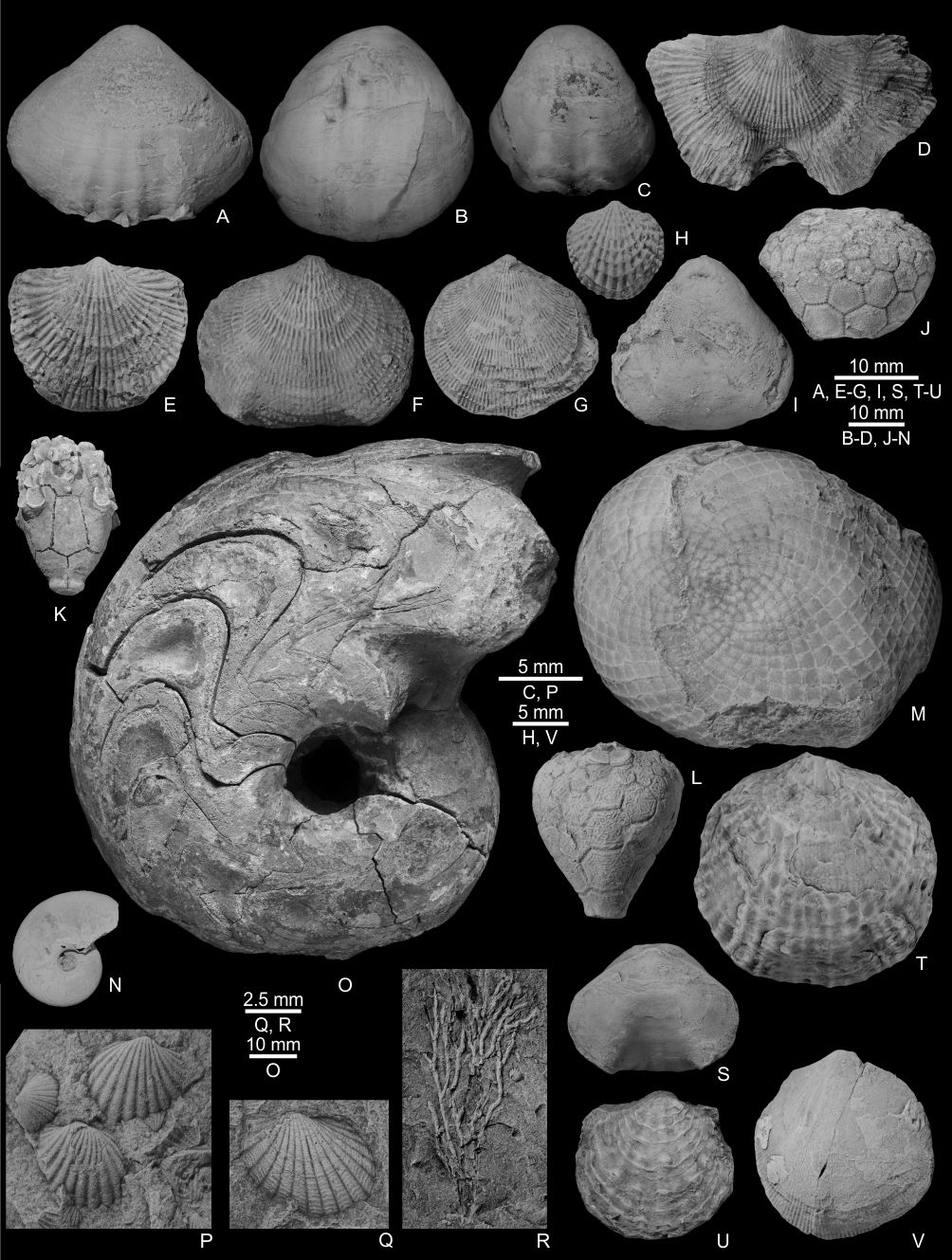

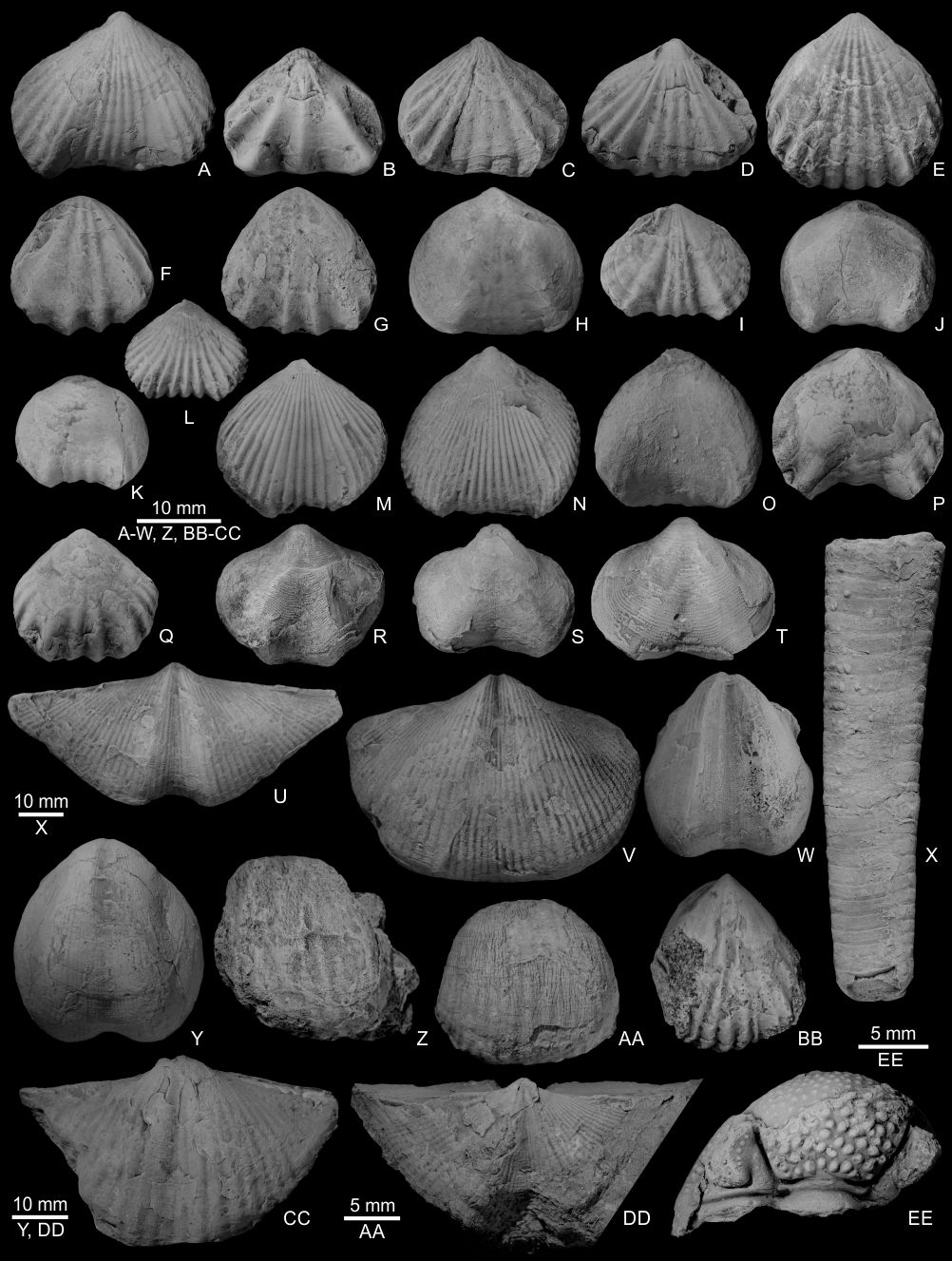

19Brachiopods from the Upper Devonian of Belgium attracted very early the attention of the geologists due to their great abundance and diversity (e.g. Murchison, 1840), although many of them are still only known by faunal lists without illustrations dating back to the first half of the 20th century (Maillieux, 1941a, 1941b). They were largely used in the past for characterising several former subdivisions of the Frasnian–middle Famennian succession (e.g. Gosselet, 1874, 1877a, 1888; Maillieux, 1914a, 1914b, 1934; Maillieux & Demanet, 1929), essentially the rhynchonellides and spiriferides: e.g. F2a, Schistes et calcaire argileux à Cyrtospirifer Orbelianus; F2i, Schistes gris à Reticularia pachyrhyncha (Maillieux, 1934, p. 414–415). Moreover, Maillieux (1914a, p. M71) qualified the Frasnian as the étage du Spirifer Verneuili, i.e. the Cyrtospirifer verneuili stage They are particularly useful for regional correlations and in the field as key fossils, especially in the monotonous shaly series such as those of the lower Famennian (Figs 5, 6).

20Frasnian brachiopod faunas from the Dinant Synclinorium were largely studied in the last decades, especially the rhynchonellides and spire-bearers (athyridides, atrypides, spiriferides), and several brachiopod zones were proposed (e.g. Godefroid, 1974, 1998; Sartenaer, 1968a, 1974a, 1979, 1999a; Godefroid & Jacobs, 1986; Mottequin, 2005a, 2008a, 2008b, 2008c). However, Upper Devonian brachiopod faunas from the rest of the Namur–Dinant Basin remain largely unstudied compared with those of the Dinant Synclinorium (Asselberghs, 1912; Vandercammen, 1963; Sartenaer, 1982). On a worldwide scale, the end of the Frasnian is marked by a severe, multifaceted biotic crisis (McGhee et al., 2013; Racki, 2020; Smart et al., 2023) that considerably affected brachiopods. The extinction of the atrypides and pentamerides in the Namur–Dinant Basin is clearly linked with the demise of the reefal environments and the progressive development of anoxia (Godefroid & Helsen, 1998; Mottequin, 2008a; Mottequin & Poty, 2016). Consequently, early and middle Famennian brachiopod faunas are impoverished in comparison with their Frasnian counterparts; they are dominated by rhynchonellides, athyridides, spiriferides and productidines (e.g. Gosselet, 1877a, 1887; Sartenaer, 1956a, 1956b, 1957a, 1957b, 1958, 1968b, 1972; Mottequin, 2005a, 2008a, 2008c). Those of the upper Famennian have never been systematically investigated in the past and are only known by unillustrated faunal lists (Maillieux, 1941a, 1941b; Lecompte & Waterlot, 1957). The Strunian brachiopod fauna, mostly including rhynchonellides, spiriferides and productidines heralds the Carboniferous ones to come (Gosselet, 1857; Sartenaer & Plodowski, 1975; Conil et al., 1986; Legrand-Blain, 1991, 1995; Mottequin & Brice, 2016).

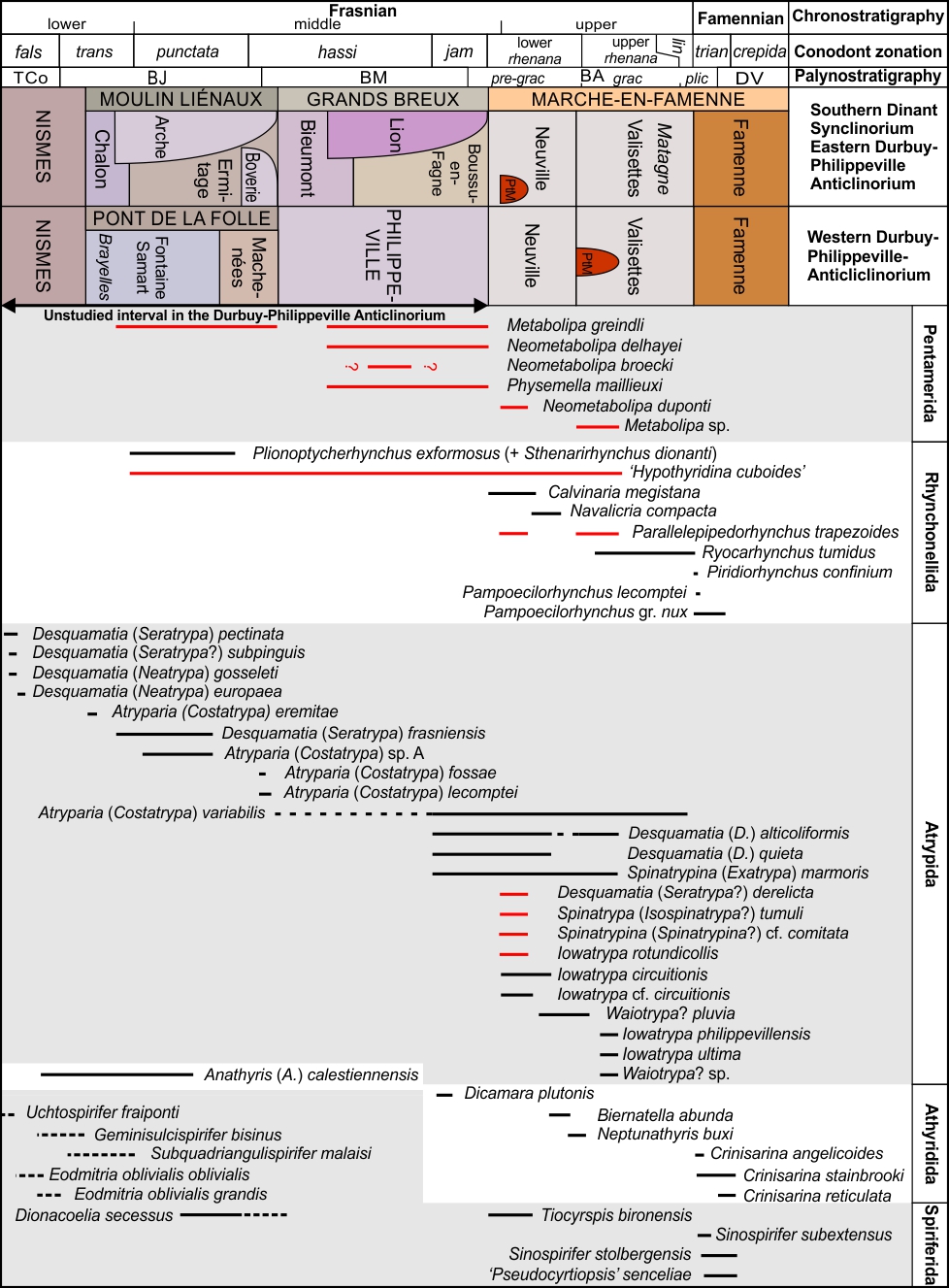

21The range of selected stratigraphically important Frasnian and lower Famennian species of athyridides, pentamerides, rhynchonellides and spiriferides is indicated in Figure 5 and the latter are illustrated in Plates 1–5. Moreover, the distribution of the rhynchonellides established by Sartenaer (e.g. 1968b, 1972, 1983) in the uppermost Frasnian and lower Famennian of the southern limb of the Dinant Synclinorium is illustrated in Figure 6.

Figure 5. Distribution of selected species of rhynchonellide, atrypide, athyridide and spiriferide brachiopods in the Frasnian and lower Famennian succession of the southern limb of the Dinant Synclinorium and the Durbuy–Philippeville Anticlinorium (Godefroid, 1999; Sartenaer, 1999a; Mottequin, 2005a, 2008a, 2008b, 2008c). Red lines indicate occurrences in mounds. Formations are in capital letters, members in regular letters. Abbreviations: fals, falsiovalis; jam, jamieae; lin, linguiformis; PtM, Petit-Mont; trans, transitans; trian, triangularis.

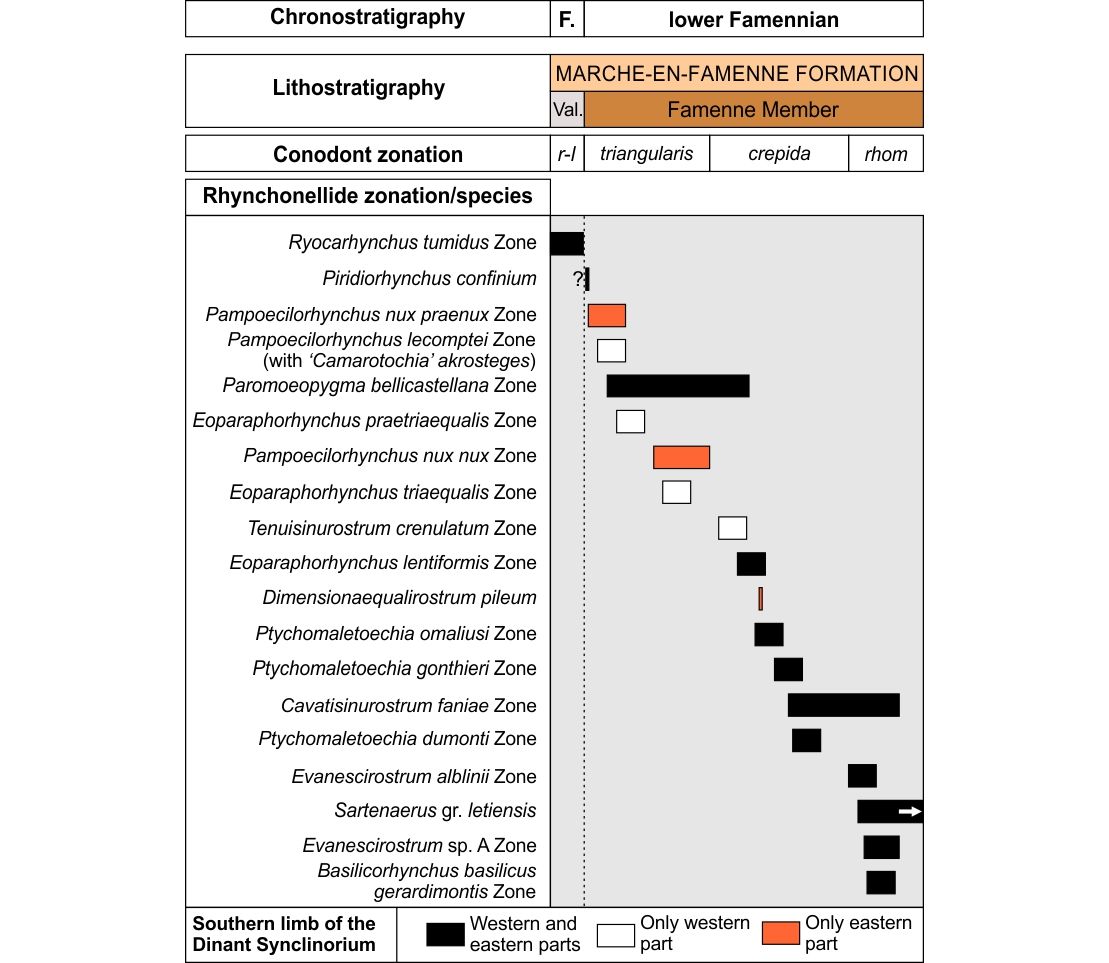

Figure 6. Rhynchonellide brachiopod zonation and species in the upper Frasnian and lower Famennian strata of the Marche-en-Famenne Formation, i.e. the Matagne Facies of the Valisettes Member and the Famenne Member, on the southern limb of the Dinant Synclinorium (modified from Sartenaer (1968b, 1972, 1983) and complemented with Sartenaer’s (1980, 2001) data); conodont zonation from Dreesen (1978). No scale. Abbreviations: F., Frasnian; rhom, rhomboidea; r–l, upper rhenana–linguiformis conodont zones; Val., Valisettes Member.

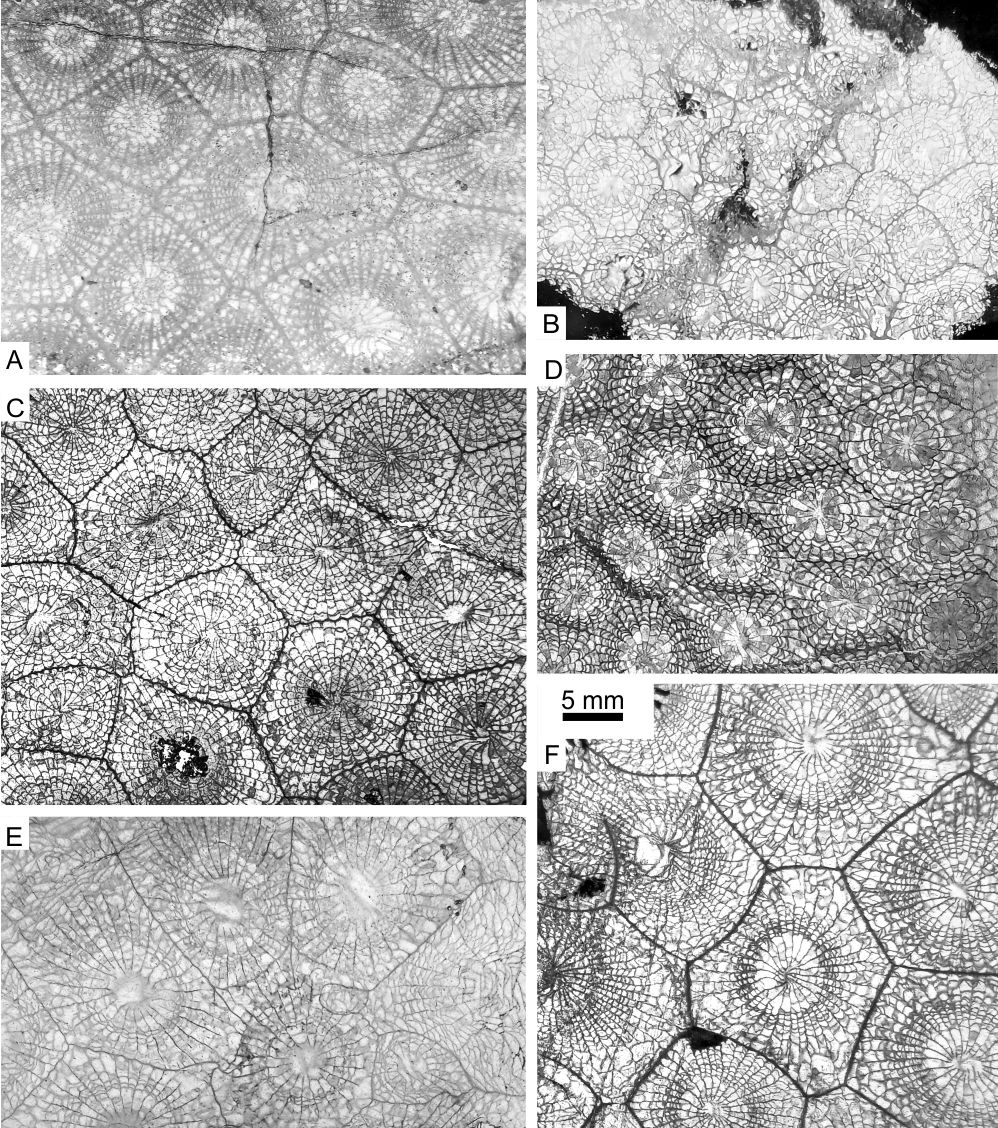

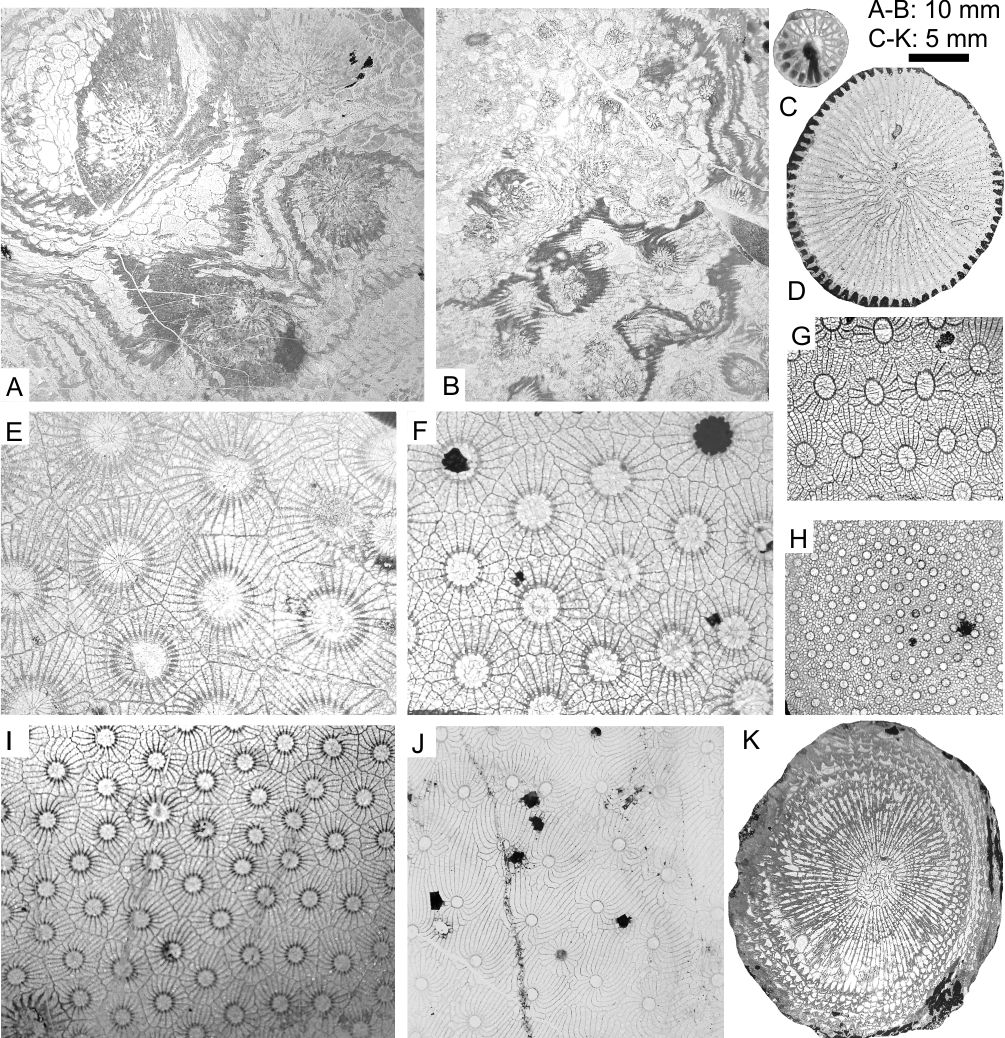

5.3. Rugose corals

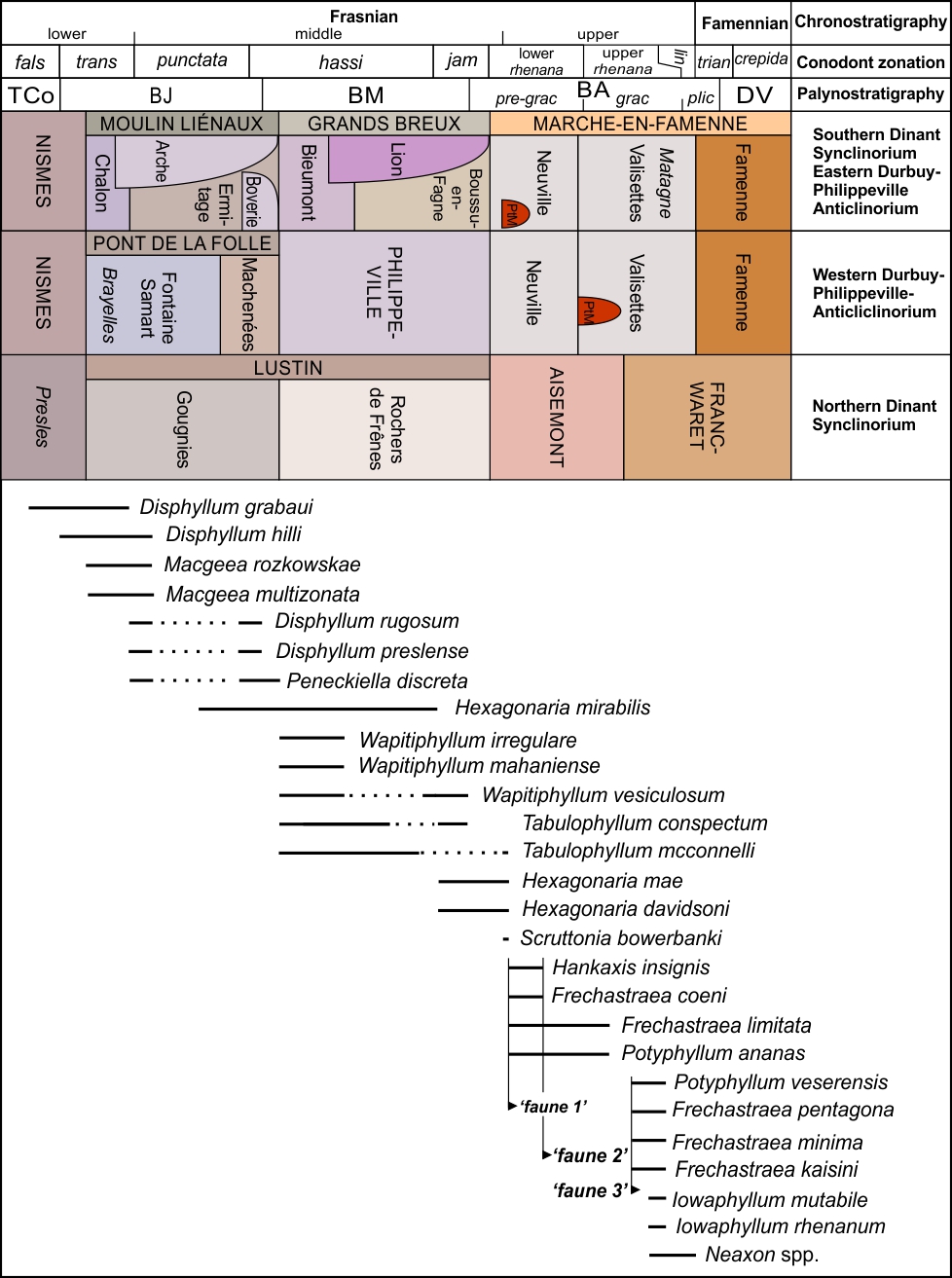

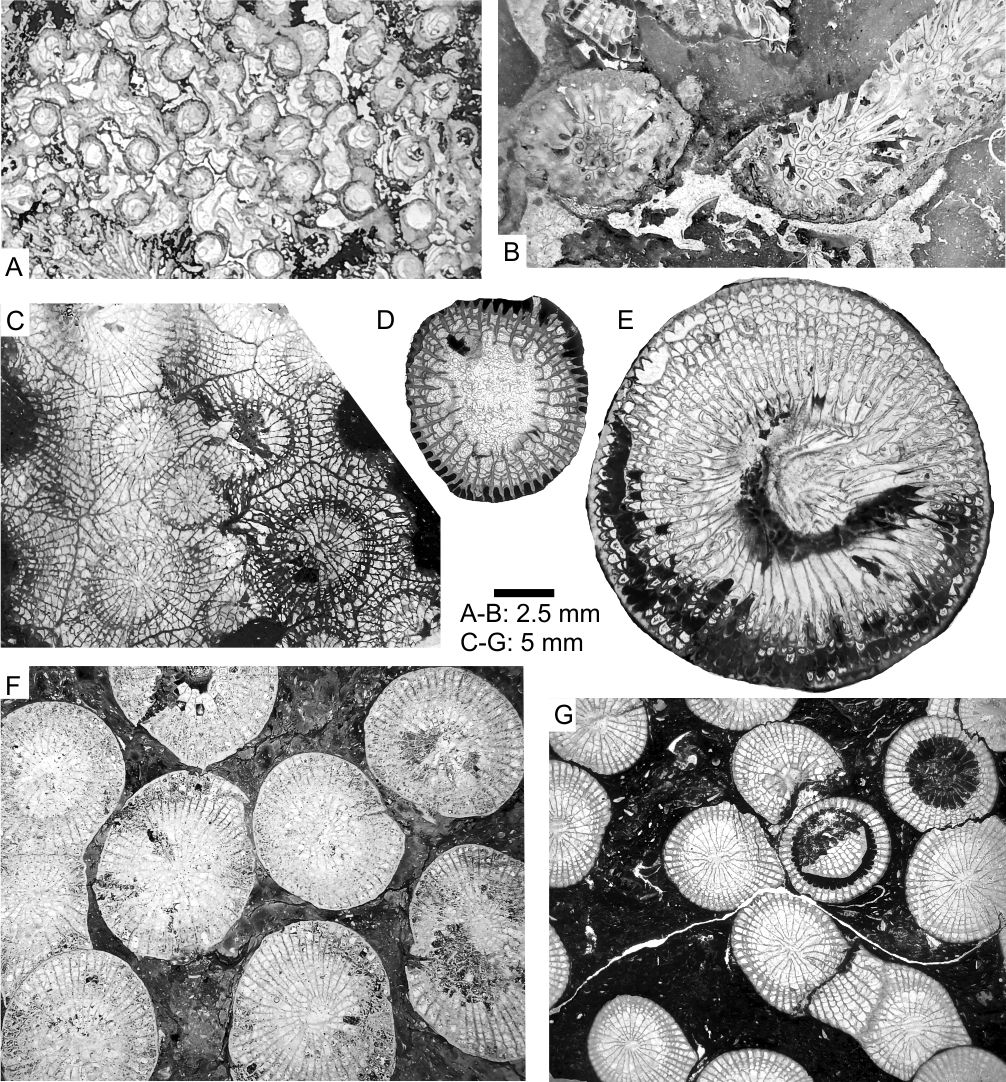

22In the Frasnian, rugose corals are abundant, though less diverse than in the Middle Devonian and are useful stratigraphic markers for regional correlations (Coen-Aubert, 1977; Tsien, 1977a, 1977b) (Fig. 7). Although no formal biozonation has been established, several fossil coral assemblages are recognised in the lower–middle Frasnian formations, characterised by the abundance of Disphyllum in the lower part, then Peneckiella, Wapitiphyllum and Hexagonaria (Tsien, 1977a, 1977b, Coen-Aubert, 1994, 1995, 2000, 2009; Boulvain et al., 2011) (Figs 8–9). A major faunal turnover is marked at the middle–upper Frasnian boundary, the Hexagonaria fauna being replaced by phillipsastreids (Tsien, 1984; Coen-Aubert, 2012). Three successive associations were described by Coen et al. (1977) in the upper Frasnian, namely faune 1, faune 2 and faune 3, mostly characterised by species of Frechastraea and Potyphyllum (Phillipsastrea in the Belgian literature) (Fig. 10). Anoxic facies on top of the Frasnian caused the demise of the corals (Paquay, 2002; Mottequin & Poty, 2016).

23Rugose corals are rare in the Famennian strata and only small undissepimented forms are described in the lower Famennian (Denayer et al., 2012). Scarce solitary corals have been described from the middle Famennian Souverain-Pré Formation (Denayer et al., 2012; Vachard et al., 2017) and its lateral equivalent in the Avesnois area (Sains Member), but most of the rugose corals are known from the upper and uppermost Famennian where Poty (in Poty et al., 2006) recognised the subzones RC0α and RC0β, respectively. The upper one includes the Strunian coral fauna dominated by Campophyllum, ‘Palaeosmilia’, Clisiophyllum and Bounophyllum, together with rarer genera (Poty, 1999; Denayer et al., 2011a) (Fig. 11).

Figure 7. Biostratigraphic zonations (conodonts and spores) of the Belgian Frasnian and range of selected corals (see section 5.3 for references). Formations are in capital letters, members in regular letters Abbreviations: fals, falsiovalis; jam, jamieae; lin, linguiformis conodont zones; PtM, Petit-Mont; trans, transitans; trian, triangularis.

Figure 8. Lower–middle Frasnian rugose and tabulate corals. Abbreviation: TS, transverse section. A. Thecostegites bouchardi in TS (BCH/1-1); Saint-Laurent quarry, Bauche, Rochers de Frênes Member. B. Thamnopora boloniensis (PAULg.20240916.1); Lion quarry, Frasnes-lez-Couvin, Lion Member. C. Hexagonaria mirabilis in TS (PAULg.20240916.2); Lion quarry, Frasnes-lez-Couvin, Lion Member. D. Macgeea rozkowskae in TS (HUC/2-5); Huccorgne, Bovesse Formation. E. Tabulophyllum conspectum in TS (NEU.742B); Neuville section, upper part of Philippeville Formation. F. Disphyllum hilli in TS (PRA.2005.19/1); Prayon, lower part of Lustin Formation. G. Disphyllum preslense in TS (PAULg.20240916.3); Huccorgne, Bovesse Formation.

Figure 9. Middle Frasnian rugose corals. Abbreviation: TS, transverse section. A. Hexagonaria mae in TS (PAULg.20240916.4); Nord quarry, Frasnes-lez-Couvin, base of Neuville Member. B. Wapitiphyllum vesiculosum in TS (PAULg.20240916-5); Huccorgne, Mehaigne Member. C. Argutastrea konincki in TS (HUC II/2a); Huccorgne, Biénonsart Member. D. Argutastrea lecomptei in TS (HUC/2-2); Huccorgne, Biénonsart Member. E. Wapitiphyllum irregulare in TS (PAULg.20240916-7); Huccorgne, Biénonsart Member. F. Wapitiphyllum mahaniense in TS (HUC/1); Huccorgne, Biénonsart Member.

Figure 10. Upper Frasnian rugose corals. Abbreviation: TS, transverse section. A. Iowaphyllum mutabile in TS (NEU 2009/21d); Neuville railway section, Valisettes Member. B. Iowaphyllum rhenanum in TS (NEU 2009/24); Neuville railway section, Valisettes Member. C. Neaxon sp. in TS (AYE/1-I); Aye section, Barvaux Facies of Marche-en-Famenne Formation. D. Macgeea gallica in TS (HON 2001/6A-15-Ib); Hony section, lower part of Lambermont Formation. E. Potyphyllum ananas in TS (FDC 2007/14-5b); Fond des Cris disused quarry, Fond des Cris Member. F. Frechastraea limitata in TS (NEU 2009/27a); Neuville railway section, Valisettes Member. G. Frechastraea pentagona in TS (AYE/1a); Aye section, Barvaux Facies. H. Frechastraea minima in TS (NEU 2010/2); Neuville railway section, Valisettes Member. I. Frechastraea coeni in TS (ENG 1993/56-54); Tchafornis quarry, Engis, Tchafornis Member. J. Frechastraea kaisini in TS (NEU 2009/26); Neuville railway section, upper part of Valisettes Member. K. Hankaxis insignis in TS (ENG 1993/56); La Mallieue section, Tchafornis Member.

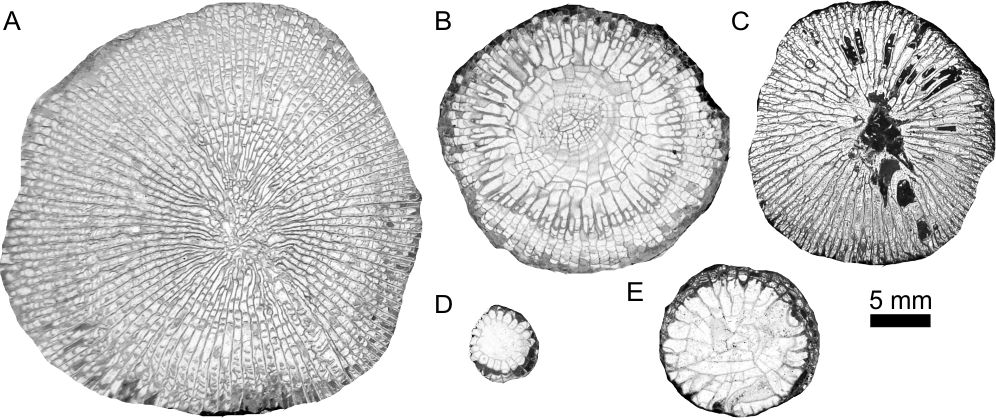

Figure 11. Famennian rugose corals in transverse section. A. ‘Palaeosmilia’ aquisgranensis (DOL/74); Dolhain section, Comblain-au-Pont Formation. B. Clisiophyllum omaliusi (KLE 9/27-21c); Kleinsteinkoten quarry, Comblain-au-Pont Formation. C. Campophyllum gosseleti (ANS 145/41); Anseremme section, Comblain-au-Pont Formation. D. Catactotoechus sp. (CHE 1993/I-1); Chevetogne, Souverain-Pré Formation. E. Bounophyllum praecursor (STO 1986/189-2); Stolberg section, Comblain-au-Pont Formation.

5.4. Foraminifers

24Foraminifers (Nanicella, Frondilina) were reported in the Frasnian, but are poorly diverse (e.g. Mouravieff & Bultynck, 1967; Coen-Aubert, 1970; Mamet et al., 1985; Schmidt, 1994; Denayer & Poty, 2010). Nanicella has not been observed above the Frasnian–Famennian Boundary (Conil et al., 1986) and it is not before the middle Famennian that foraminifers occurred again in the Namur–Dinant Basin, i.e. within the calcareous Souverain-Pré Formation and the Baelen Member (Bouckaert et al., 1967; Conil & Lys, 1970; Dreesen, 1978; Dreesen et al., 1985; Conil et al., 1986; Vachard et al., 2017). Conil et al. (1977) introduced the Df3 Zone for the Famennian, to the exception of the strata preceding the Souverain-Pré Formation, that was based on the evolution of the plurilocular genus Quasiendothyra and subdivided it into several subzones (Df3α–ε). The latter were renamed DFZ3–7 by Devuyst & Hance (in Poty et al., 2006) for more coherence with the Mississippian foraminifer zonation (prefixed MFZ) (Fig. 3). Furthermore, several species formerly ascribed to Quasiendothyra were later assigned to Endothyra (see references in Devuyst & Hance in Poty et al., 2006). Although the base of the uppermost Famennian (Strunian) is not yet formally defined (see above), calcareous foraminifers became valuable for biostratigraphy from the base of the succession traditionally ascribed to this regional substage in Belgium and northern France (Bouckaert et al., 1968; Conil & Lys, 1968; Conil, 1980; Conil et al., 1986). The Strunian DFZ7 is characterised by a rich association including notably Quasiendothyra kobeitusana and Q. konensis (see Denayer et al., 2021 and references therein). The former DFZ8, with Tournayellina pseudobeata as the guide for its base (Devuyst & Hance in Poty et al., 2006), is considered now to be coeval with the depleted MZF1, thus of basal Tournaisian age (Hastarian) (see discussion in Denayer et al., 2021).

5.5. Ostracods

25Ostracods were used to establish a biostratigraphic zonation of the Upper Devonian succession of Belgium. The first was proposed by Magne (1964) for the Frasnian of the ‘Namur Synclinorium’ and a second was proposed by Lethiers (1974a) for the Frasnian and Famennian of the Dinant Synclinorium, based on the research of Becker (1971) and Lethiers (1973). Casier (1975, 1977, 1979, 1982) introduced another zonation (see also Casier & Coen, 1999) whereas Lethiers (1984) refined his previous one. Besides these papers, the reader will also consult Lethiers (1974b) and Casier (2018) for the ostracods at the Frasnian–Famennian boundary, and Becker & Bless (1974), Becker et al. (1974), and Casier et al. (2004) for those of the Strunian of Belgium. Note that the ostracod biozonations of the Belgian Upper Devonian are not used here.

5.6. Palynomorphs

26The Frasnian formations of the proximal depositional areas yield some palynomorph assemblages, among which several biozones are recognised, mostly from subsurface (Loboziak & Streel, 1980, 1981, 1988; Loboziak et al., 1983, 1991; Streel & Loboziak, 1987). The palynological succession is better known in the French (Boulonnais) and German (Eifel) neighbouring areas due to more suitable facies (Streel et al., 1987, 2021). In the more distal zone, the palynological assemblages are largely dominated by acritarchs which were mostly studied in the middle–upper Frasnian (e.g. Dricot, 1965, 1967; Vanguestaine et al., 1999) and across the Frasnian–Famennian boundary (e.g. Vanguestaine et al., 1983; Martin, 1981, 1982, 1984; Streel & Vanguestaine, 1989; Vanguestaine, 1999).

27The lower–middle Famennian interval is particularly poor in palynomorphs (‘lower–middle Famennian vegetation crisis’ in Streel et al., 2001), with a single zone encompassing all the Famennian strata below the Souverain-Pré Formation (Streel, 2009). The palynological zonation is much better developed and used in the upper and uppermost Famennian that displays more suitable facies and three to six zones are identified (depending on the zone concept of the authors). Streel (1966) and Bouckaert et al. (1968) introduced the first palynostratigraphic zones that were subsequently emended by Bouckaert et al. (1969, 1970), Paproth & Streel (1970), Becker et al. (1974), Streel et al. (1987), Higgs et al. (1988, 2000, 2013), and Loboziak et al. (1994) (Fig. 3). Recent palynological research particularly focused on the uppermost Famennian and the Devonian–Carboniferous Boundary (Higgs et al., 1992; Maziane & Vanguestaine, 1997; Maziane et al., 1999, 2002, 2007; Streel, 2005; Prestianni et al., 2016, Denayer et al., 2021).

6. Evolution of the Namur–Dinant Basin in the Late Devonian

28The Frasnian starts with a shaly unit following an important gap on the carbonate platform that was initiated at the end of the Givetian (Frasnes Event sensu Becker, 1993). In some parts of the basin, it is marked by an oolitic ironstone horizon which consists of ferruginised allochems (ooids, pisoids, coated bioclasts, intraclasts). In the Presles Facies of the Nismes Formation, these grains are typically haematitised (oxidised facies) whereas in the rest of this formation, the iron is at the reduced state in complex silicates such as berthierine, chamosite and chlorite (de Magnée, 1933).

29Above the shaly Nismes Formation, the carbonate factory restarts, with the development of platform carbonates throughout the basin, with the exception of its southern margin, where the carbonate production is limited to isolated buildups. A first third-order sequence (UD1 on Fig. 3) is recorded in the Moulin Liénaux Formation, with the initiation of a carbonate sole (Chalon Member) (Figs 3, 4). During the transgressive system tract, the latter allows the local development of bioherms that evolve into isolated platforms (Arche Member) in the course of the highstand system tract and are capped by an emersion surface. The lowstand system tract is recorded by argillaceous deposits (Ermitage Member) around the aforementioned limestone bodies. A second, very short third-order sequence (UD2) is recorded in the Boverie Member of the Moulin Liénaux Formation but apparently not on the shelf. The third sequence, which was designated ‘Lion sequence’ (UD3) in Mottequin & Poty (2016), is similarly organised, with a sole (Bieumont Member) and bioherms evolving into isolated platforms (Lion Member) surrounded by shale (Boussu-en-Fagne Member) that deposited after the development of the Lion Member bioherms. In the northern area, these three sequences are recorded in the development of the Pont-de-la-Folle (sequence UD1-2?) and Philippeville formations (UD3) and in the Lustin Formation (UD1-(2?-)3), capped by an emersion surface. The fourth sequence (UD4, named ‘Aisemont sequence’ in Poty & Chevalier, 2007) starts with the transgressive Neuville Member and its highstand is recorded in the Valisettes and Petit-Mont members in the southern depositional areas; it corresponds to the tripartite Aisemont Formation in the northern areas. The lower Kellwasser Event corresponds to the maximum flooding interval of this sequence and to the development of dysoxic-anoxic shale in the distal part of the Namur–Dinant Basin. The fifth sequence (UD5, named ‘Lambermont sequence’ in Mottequin & Poty, 2016) almost entirely records shaly argillaceous deposits (Matagne and Barvaux facies, and Lambermont Formation), with few limestone at the base (Petit-Mont and Verviers members), and is marked by the global development of oceanic anoxia triggered by the upper Kellwasser Event at the end of the Frasnian.

30The argillaceous depositional context that characterises the upper Frasnian continued through a large part of the lower Famennian with no major changes of facies across the Frasnian–Famennian Boundary. In proximal areas, the basal Famennian is characterised by the oolitic ironstone beds developed in the Franc-Waret and Hodimont formations. They correspond to the horizon I of Dreesen (1981) (Fig. 3). Lithologically, they consist of lenticular limestones (packstones/grainstones) enriched with different types of ferruginised allochems (ooids, pisoids, oncoids, intraclasts of algal mat origin, rolled bioclasts) (Dreesen, 1981), whereas the source of the iron seems to be related to volcanic activity on the basis on rare earth element evidence (Laenen et al., 2002). Dreesen et al. (1986a) and Dreesen (1989a) demonstrated that they are synchronous with volcano-sedimentary events recognised in the nearby Rhenish Basin; therefore, these oolitic ironstone horizons are key stratigraphic markers that are well dated by conodonts (e.g. Dreesen, 1984). They are interpreted as lowstand deposits reworked during early stages of transgressions, probably by storm events (Dreesen, 1981, 1982a, 1982b, 1989a, 1989b), marking the base of the third-order sequences UD6-7 (Fig. 3).

31Another oolitic ironstone horizon (horizon II of Dreesen, 1981) occurs within the lower Famennian shaly formations and two others (horizons IIIa and IIIb in Dreesen, 1982a) are situated at their top. The latter correlates eastwards with the Cheiloceras limestone of western Germany (Dreesen, 1982a). The Esneux Formation is the prelude to the sandy depositional environments that will characterise the upper Famennian succession of Belgium. The Souverain-Pré Formation is a transgressive carbonate unit locally underlined by the ironstone horizon IV of Dreesen (1982a) (third-order sequence UD8, Figs 3, 4, 12). It consists of nodular, stylo-brecciated, silty limestone, commonly sandy in proximal areas and argillaceous in distal parts, with a strongly diachronic base (upper marginifera conodont Zone in the south of the basin, lower trachytera conodont Zone in the northern parts) (Dreesen, 1978). In the Vesdre area, the Formation includes the Baelen Member that constitutes one of the rare examples of Famennian stromatactis–crinoid–calcimicrobe bioconstruction known worldwide (Dreesen et al., 1985, 2013).

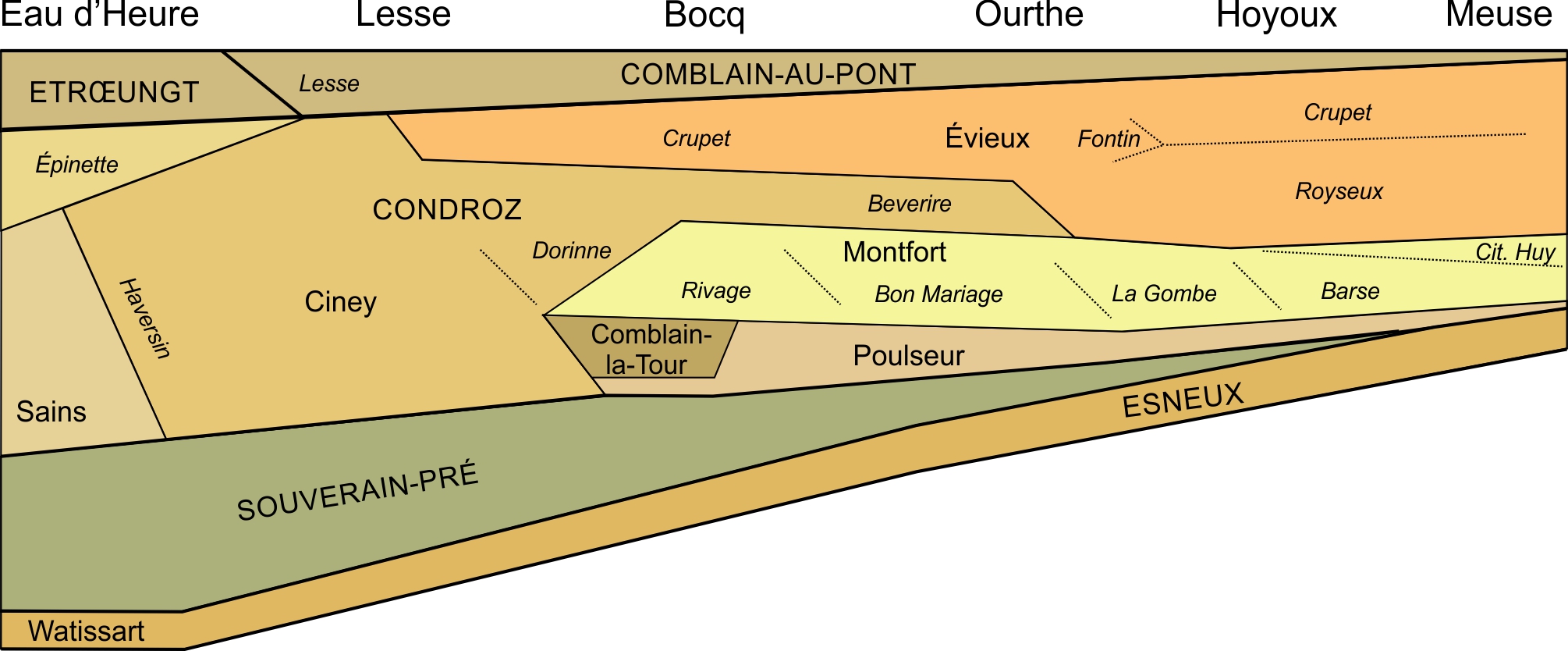

32After this carbonate episode, the siliciclastic sedimentation resumes with the Condroz Formation (Fig. 12). This thick formation contains a variety of coastal environments, ranging from predominantly ‘fully’ marine in the lower part (Poulseur and Montfort members) to non-marine environments towards the top, eventually transitioning to sabkha and fluvial channel environments in the Évieux Member. This member yielded vertebrates (including tetrapods), arthropods and a diverse flora (see Prestianni & Gerrienne, 2015; Olive et al., 2015; Denayer et al., 2016). Distally, the Montfort and Évieux members pass to a thick sequence of siliciclastic and carbonate alternations (Ciney Member), which grades to the purely marine shaly unit of the Sains Member in the south-western part of the basin (Avesnois area) (Thorez et al., 1988).

33The lateral correlations of facies within the Condroz Formation were made possible by the recognition of twelve remarkable synchronous horizons of ball-and-pillow structures (pseudonodules in the literature; Ancion & Macar, 1947; Macar, 1948), supposedly triggered by seismic shocks related to synsedimentary tectonics (Thorez et al., 2006).

34The Évieux Member and its lateral equivalents witness the maximum of regression of the Famennian age (recorded as a third-order sequence UD9, Fig. 3). It is followed by the major Strunian transgression that is marked by the return of marine conditions and the recolonisation by marine fauna (e.g. brachiopods, corals, trilobites) in the Comblain-au-Pont and Etrœungt formations. It corresponds to the lower part of sequence 1 of Hance et al. (2001). The Hangenberg Crisis is recorded at the top of this unit, where dysoxic shale locally developed (Hangenberg Black Shale Event), whereas the out-of-sequence Hangenberg Sandstone Event and the Devonian–Carboniferous Boundary is recorded within the basal bed of the overlying Hastière Formation (see Denayer et al., 2021 for a recent synopsis).

Figure 12. Middle–uppermost Famennian formations within the Dinant Synclinorium and the Haine–Sambre–Meuse Overturned Thrust sheets (origin of data: see main text). Formations are in capital letters, members in regular letters, and facies in italics. Abbreviation: Cit. Huy, Citadelle de Huy.

7. Description of the lithostratigraphic units

7.1. Preliminary remarks

35All the lithostratigraphic units are listed alphabetically as a lexicon, notwithstanding their age and geographic distribution. The reader is referred to the Figures 3 and 4 for further information concerning the latter data, that are complemented by Figures 12, 23 and 25, and to Figures 5–7 for the distribution of selected brachiopod and rugose coral species. Macrofossils are illustrated in Plates 1–5 (e.g. brachiopods, bivalves, cephalopods, trilobites, plants) and Figures 8–11 (mostly rugose corals).

36We have indicated the oldest references (e.g. including the original spelling), which may explain some discrepancies between the present work and previous ones (Boulvain et al., 1993a, 1999a; Bultynck & Dejonghe, 2002), as is notably the case for the Esneux and Comblain-au-Pont formations. A history of the subdivisions of the Frasnian of the Dinant Synclinorium, Brabant Parautochthon and Vesdre area was provided by Boulvain et al. (1999a) and complements those published by Dumon et al. (1954), Coen (1974), Tsien (1974), and Boulvain et al. (1993a), which also dealt with the units present outside these areas. Bellière (1954), Dreesen (1978) and Thorez et al. (2006) published a history of the Famennian subdivisions of the abovementioned areas. Most of the descriptions provided in this chapter are synthetised from previous publications such as the abovementioned lithostratigraphic charts, complemented by more recently published data, including those from the revised Geological Map of Wallonia. To be consistent with the latter, new names are proposed for units that were previously grouped together for mapping purposes, such as the Montfort and Évieux formations, which are here transformed into members of the newly introduced Condroz Formation, whereas units previously described as Famennian members are here considered to be facies (e.g. Beverire and Spontin facies). Moreover, informal members (e.g. membre biostromal de Lustin), remarkable horizons (e.g. Hony Horizon) and facies (e.g. Merlemont Dolomitic Facies) are also introduced with formal definitions. As far as possible, existing names have been retained, unless they are confusing or already used for distinct units. Additionally, the definition of the boundaries of some units (e.g. Lambermont and Esneux formations) has been modified to facilitate the geological mapping process.

7.2. Descriptions

Aisemont Formation – AIS

37Origin of name. After the village of Aisemont, Assise d’Aisemont in Graulich (1961, p. 39, 68). This term does not have to be confused with the Grès et psammites d’Aisémont of Cornet (1923, p. 181) and the Psammites d’Aisémont of Cornet (1927, p. 496), which have fallen into disuse; they would correspond to the Rouillon Member of the Eifelian Rivière Formation (see Denayer et al., 2024).

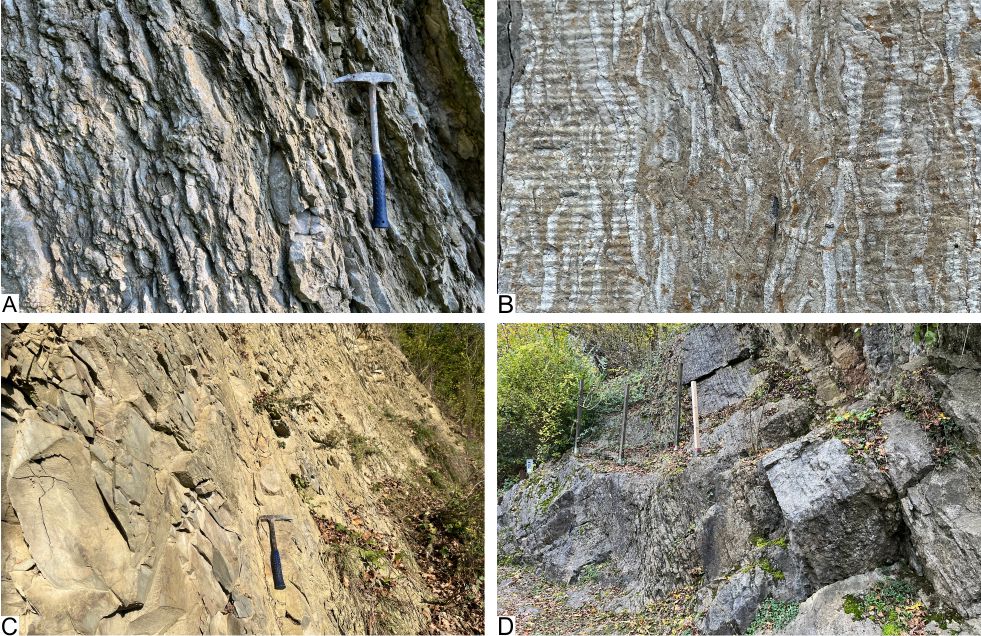

38Description. In its type area, the Aisemont Formation (Fig. 13) rests abruptly on the limestone of the Lustin Formation and is covered by the shale of the Franc-Waret Formation (Delcambre & Pingot, 2014b). It is characterised by two carbonate members (premier and second biostrome à Phillipsastrea sensu Coen, 1974; Coen-Aubert, 1974a, 1974b; Coen et al., 1977; Coen-Aubert & Lacroix, 1979) that are separated by a shaly interval. These lower, middle and upper terms or members of the literature (e.g. Lacroix, 1999a; Poty & Chevalier, 2007; Denayer & Poty, 2010) are formally named herein and are the following, in ascending order: the Tchafornis, Mallieue and Fond des Cris members.

39In its stratotype at Engis, the c. 6 m thick Tchafornis Member – TCH (from the disused Tchafornis quarry at Engis) begins with c. 0.5 m thick bioturbated limestone rich in siliceous sponge spicules, crinoid ossicles and colonial corals (Frechastraea, Alveolites) (Poty & Chevalier, 2007). This is followed by an almost 4 m thick biostromal episode formed by the accumulation of discoid colonies of rugose corals (mainly Frechastraea) (Fig. 13A, B), which can represent up to 90% of the volume of the rock (Poty & Chevalier, 2007). The biostromal level passes vertically to argillaceous limestone, more or less dolomitized, with numerous rugose (Frechastraea, Hankaxis and Phillipsastrea) and tabulate (Alveolites, auloporides) corals, then to argillaceous dolostone. In more distal areas, tabulate corals and scarce stromatoporoids are also present in various proportions (Poty & Chevalier, 2007).

40The Mallieue Member – MLL (from the La Mallieue section along the road N617 at Engis) is essentially composed of green to brown and black shales (Fig. 13C). In its type section, where it reaches 13 m in thickness, it starts with a 0.7 m thick bed of calcareous shale, more or less dolomitized, followed by 4 m of shale almost devoid of fossils, then 7.3 m of shale, sometimes calcareous and ends with 1 m of calcareous shale passing to argillaceous limestone. Brachiopods (e.g. lingulides, productidines, spiriferides) can be abundant, but numerous molluscs (bivalves, orthoconic cephalopods, gastropods) are also present, essentially in the third part of the Member (Mottequin et al., 2015; Goolaerts et al., 2017). The Mallieue Member may incorporate very locally (Chaudfontaine boreholes) grey and red, or even pink limestone that was interpreted as forming a bioherm similar to those of the Petit-Mont Member (Graulich, 1967; Coen-Aubert, 1974a; Graulich & Vandenven, 1978; Dejonghe, 1987a; Boulvain, 1993b), but this limestone most probably corresponds to biostrome such as those of the Tchafornis Member that are reddish in the area and thickened by local tectonics. The Mallieue Member corresponds to the lower Kellwasser Event (Poty & Chevalier, 2007; Denayer & Poty, 2010; Mottequin & Poty, 2016).

41The Fond des Cris Member – FDC (from the disused Fond des Cris quarry at Ninane (Chaudfontaine)) consists of grey to black stylonodular bioclastic limestone (Fig. 13D), often dolomitized, with numerous oncoids and rugose (Potyphyllum, Frechastraea) and tabulate (Alveolites) corals (Denayer & Poty, 2010) (Fig. 10E). This Member does not have to be confused with the Famennian psammites du Fond des Crys introduced by Mourlon (1875b, p. 772), a local name that is no longer in use.

42Stratotype and sections. The stratotype of the Aisemont Formation is located in the northern part of the former Moreau quarry at Aisemont (e.g. Lecompte, 1960; Lacroix, 1974a; Delcambre & Pingot, 2014b), which was transformed into a controlled landfill (Lacroix, 1999a); therefore, the section is now almost lost. The Tchafornis and Mallieue sections (e.g. Poty & Chevalier, 2007; Denayer & Poty, 2010; Mottequin et al., 2012), both situated on the left bank of the Meuse River valley at Engis, are easily accessible and selected herein as the respective stratotypes of the eponymous members. Moreover, the Mallieue section (road and disused quarry) exposes the entire formation. In the latter section, the proximal facies of the Fond des Cris Member are dolomitized as is the case at Aisemont. The Fond des Cris section, located in the disused quarry close to the Ninane cemetery in the Fond des Cris Creek valley near Chaudfontaine, was described by Da Silva (2004) and Denayer & Poty (2010) and is selected here as the stratotype of the eponymous member.

43Area and lateral variations. The Aisemont Formation is recognised in the Brabant Parautochthon, from the meridian of Marchovelette (Asselberghs, 1936; Delcambre & Pingot, 2015), east of the Orneau River valley, where it lies on the Rhisnes Formation, to the east of the Mehaigne River valley (Delcambre & Pingot, 2015), where it rests on the Huccorgne Formation. In the Campine Basin, the Aisemont Formation lies directly on top of the siliciclastic Booischot Formation (Booischot borehole) and probably on the Rhisnes Formation (rather than the Huccorgne Formation) in the Heibaart borehole (Lagrou & Coen-Aubert, 2017). The Formation is also recognised in the Visé area, in the eastern extension of the Brabant Inlier (e.g. Poty, 1982, 1991; Poty & Delculée, 2011) and in the Bolland borehole (Graulich, 1975a, 1984). Outside the Brabant Parautochthon and the Campine Basin, this lithostratigraphic unit invariably overlies the Lustin Formation. In the Haine–Sambre–Meuse Overturned Thrust sheets, the Aisemont Formation is known from Landelies (Delcambre & Pingot, 2000a) to Engis (Delcambre, in press, a). On the northern flank of the Dinant Synclinorium, it crops out between Lesves (Delcambre & Pingot, 2017) to the west and Remouchamps (Coen, 1974; Marion et al., in press) to the east, and from both localities, it progressively passes laterally to the Neuville Member of the Marche-en-Famenne Formation (Delcambre & Pingot, 2004; Bellière, 2015; Marion & Barchy, in press, a).

44The Aisemont Formation is known from the Vesdre area, up to Raeren and the German border (Coen-Aubert, 1974a). In this area, the limestones of the Tchafornis Member are sometimes red-coloured (see below) (Delcambre et al., in press) and the Fond des Cris Member can form a thick carbonate mass separated by some shaly horizons (Coen-Aubert, 1974a; Laloux et al., 1996a). Eastwards, in Germany, the Aisemont Formation passes laterally to the Schmidthof-Formation (Deutsche Stratigraphische Kommission, 2016; ex Frasnium-Knollenkalke of Holzapfel, 1910).

45According to Lacroix (1999a) and Poty & Chevalier (2007), lateral variations are observed in the thickness and the abundance of the rugose corals and brachiopods in the Tchafornis Member, and in the dolomitization and dedolomitization of the Fond des Cris Member (for more details, see, e.g., Coen-Aubert, 1974a; Dejonghe, 1987b; Denayer & Poty, 2010).

46Thickness. Significant thickness changes occur laterally. In the Brabant Parautochthon, it varies a lot: 0 m near the Orneau River valley, 10–15 m in the Gelbressée Creek valley (Delcambre & Pingot, 2015), 25 m in the Mehaigne River valley (Delcambre & Pingot, 2014b), and 33 m in the Wépion borehole (Coen-Aubert, 1988). It is 25–30 m thick in the Campine Basin (Lagrou & Coen-Aubert, 2017). In the Haine–Sambre–Meuse Overturned Thrust sheets, the following thicknesses are reported: 10 m at Landelies in the Sambre River valley (Delcambre & Pingot, 2000a), 15 m at Dave in the Meuse River valley (Delcambre & Pingot, 2017), 27 m at Huy-Statte (Coen-Aubert & Lacroix, 1979), and 29 m at Engis (Poty & Chevalier, 2007). On the northern limb of the Dinant Synclinorium, it thickness is less than 30 m at Lustin in the Meuse River valley (Delcambre & Pingot, 2017), 35 m at Vierset-Barse in the Hoyoux River valley (Coen-Aubert, 1973; Coen-Aubert & Lacroix, 1979), 46 m at Baugnée (Poty & Chevalier, 2007), and up to 60 m at Remouchamps in the Amblève River valley (Marion et al., in press). In the Vesdre area, its thickness should be quite variable (25 to 100 m), notably due to the great development of the Mallieue Member (c. 65 m) in the Les Surdents area and that of the Fond des Cris Member (c. 25 m) between Pepinster and Ensival–Lambermont (Coen-Aubert, 1974a; Laloux et al., 1996a); nevertheless, these thicknesses seem to be overestimated, probably as a result of local tectonics.

47Age. Late Frasnian; lower rhenana and lowest part of the upper rhenana conodont zones (Coen-Aubert & Lacroix, 1979, 1985; Gouwy & Bultynck, 2000; Bultynck & Dejonghe, 2002). Coen et al. (1977) reported two rugose coral associations, namely faune 1 and faune 2 in the Tchafornis and Fond des Cris members, respectively. Both associations are dominated by Frechastraea limitata, F. coeni and Potyphyllum ananas (Fig. 10E, F, I). The first contains additionally Hankaxis insignis (Fig. 10K), whereas the second is characterised by the occurrence of Macgeea gallica and Frechastraea pentagona (Fig. 10D, G) Coen-Aubert, 1974a, 1974b, 2012, 2015, 2016). The smooth rhynchonellides Calvinaria megistana (probably misidentified with the spiriferide ‘Minatothyris maureri’ in the Belgian literature) (Pl. 2.A) and Navalicria compacta (Pl. 2.B) are known from the base of the Formation as is the case of the spiriferide Tiocyrspis bironensis (Pl. 2.K) (Mottequin, 2005a; Poty & Chevalier, 2007; Mottequin & Poty, 2022; see Marche-en-Famenne Formation).

48Use. Locally, the limestone was used for lime production and, accessorily, as building stone, notably the reddish (in fact pinkish orange) limestone of the Fond des Cris quarry that was used as an ornamental stone (e.g. Perron of Liège and Fourmarier Spring in Chaudfontaine) and known as the Marbre rouge (et blanc) de Chaudfontaine (Groessens, 1981).

49Main contributions. Lacroix (1974a, 1999a), Coen-Aubert (1974a, 2012, 2015, 2016), Coen-Aubert & Coen (1975), Coen et al. (1977), Coen-Aubert & Lacroix (1979), Schmidt (1994), Vanbrabant et al. (2003), Da Silva (2004), Poty & Chevalier (2007), Denayer & Poty (2010).

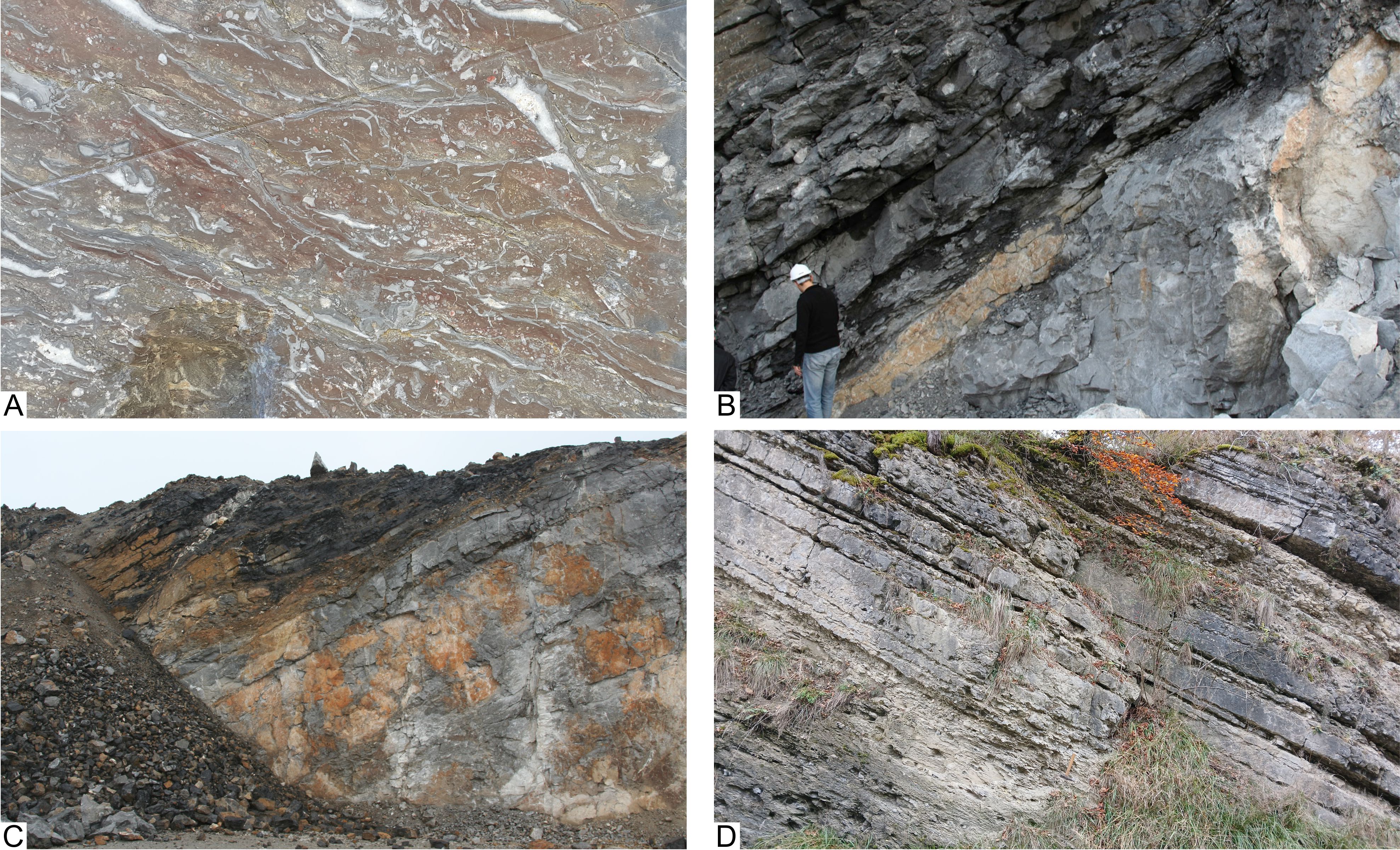

Figure 13. Illustration of the Aisemont Formation; the layers are overturned in each photograph, except D. A. Biostromal bed made of flat colonies of the rugose coral Frechastraea spp. at the base of the Tchafornis Member. Engis, Tchafornis quarry. B. Biostromal bed of discoid phillipsastreid rugose corals (Tchafornis Member) used as a door frame. Ninane, rue du Centre (width of the picture c. 17 cm). C. Green, fossiliferous shale of the upper part of the Mallieue Member. Engis, La Mallieue section. D. Lower part of the limestone of the Fond des Cris Member. Ninane, rue Fond des Cris.

Arche Member – ARC

50See Moulin Liénaux Formation.

Aye Facies

51See Marche-en-Famenne Formation (Famenne Member).

Baelen Member – BAE

52See Souverain-Pré Formation.

Barse Facies

53See Condroz Formation (Montfort Member).

Barvaux Facies

54See Marche-en-Famenne Formation (Valisettes Member).

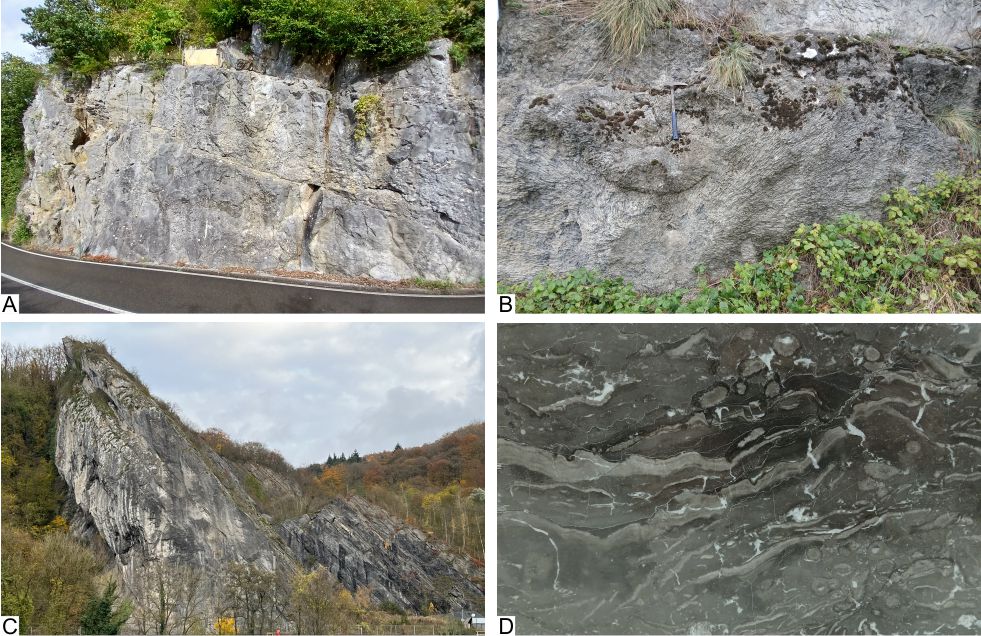

Beverire Facies

55See Condroz Formation (Ciney Member).

Biénonsart Member – BIN

56See Huccorgne Formation.

Bieumont Member – BMT

57See Grands Breux Formation.

Bois de la Rocq Formation – BDR

58Origin of name. After the Bois de la Rocq quarry in the Samme River valley near Feluy, Membre du Bois de la Rocq in Doremus & Hennebert (1995a, p. 11). Note that Mourlon (1875b, p. 789) introduced the psammite de la Roq that clearly refers to this formation.

59Description. The Bois de la Rocq Formation (Fig. 14A) corresponds to the complexe arénacé basal or séquence de base arénacée of the literature (e.g. Coen-Aubert et al., 1981) and rests on the top of the upper Frasnian–lower Famennian shale of the Franc-Waret Formation. It contains reddish and greenish coarse-grained sandstone with some red shale intercalations near its lower boundary. Locally (e.g. Tournai borehole), conglomerate occurs at the base. The sandstone is micaceous and usually displays a dolomitic cement or, occasionally, a calcareous cement. In the lower part of the Formation, the sandstone beds are usually thin, and their thickness increases upsection. The dominant colour passes from red to yellowish grey. Locally (Orneau River valley), dark fine-grained limestone beds with ostracods occur near the base. In the upper part, calcareous sandstone, commonly fossiliferous (e.g. bivalves, Pl. 5.A), occurs. The upper boundary is defined by the first thick bed of calcareous or dolomitic sandstone of the overlying Feluy Formation.

60Stratotype and sections. The stratotype corresponds to the disused Bois de la Rocq quarry along the Samme River north of Feluy. The Falnuée railway section (Conil, 1964; Delcambre & Pingot, 2008) in the Orneau valley offers a good parastratotype.

61Area and lateral variations. The Formation is known from the Brabant Parautochthon from Western Flanders (Higgs et al., 1992) and Tournai and Leuze boreholes (Coen-Aubert et al., 1981) to the Ligne River valley; it then reappears eastwards in the Orneau River valley and up to the Somme Creek valley (Vezin) where it disappears along the Landenne Fault (Delcambre & Pingot, 2014b; Delcambre, 2023).

62Thickness. In its type locality, the Formation is c. 50 m thick (Doremus & Hennebert, 1995a). A similar thickness is known in the Tournai borehole (Coen-Aubert et al., 1981). In the Orneau River valley, the top is probably missing and the Formation is 45 m thick and directly overlain by the Tournaisian Pont d’Arcole Formation (Delcambre & Pingot, 2014b). At Marche-les-Dames it reaches 60 m (Delcambre & Pingot, 2015).

63Age. Late Famennian to Tournaisian (Hastarian). Leriche (1922) indicated the occurrence of Holoptychius and Archaeopteris in the Mévergnies quarries. Coen-Aubert et al. (1981) reported Quasiendothyra communis in the carbonate unit at the top of this formation, suggesting a latest Famennian (Strunian) age. In the Bossuit borehole, north of Tournai, Higgs et al. (1992) mentioned the lower Tournaisian VI to HD palynozones for the upper part of the complexe arénacé basal, i.e. the top of the Bois de la Rocq Formation and the base of the overlying Feluy Formation.

64Use. Locally used as building stone.

65Main contributions. Mourlon (1875b), Asselberghs (1936), Conil (1959), Bouckaert & Conil (1970), Coen-Aubert et al. (1981), Higgs et al. (1992), Doremus & Hennebert (1995a), Hennebert & Eggermont (2002).

Figure 14. Illustration of some Upper Devonian units. A. Thickly bedded sandstone of the Bois de la Rocq Formation. Marche-les-Dames quarry. B. Lower part of the Bovesse Formation. Huccorgne road section. C. Robiewez (lower part) and Mehaigne (upper part) members of the Huccorgne Formation. Huccorgne quarry.

Bois des Mouches formation

66Remark. The Bois des Mouches formation is a disused unit introduced by Delcambre & Pingot (2000a, p. 25) corresponding to the Condroz Formation. It encompasses the entire Famennian succession between the basal Famennian shale (Franc-Waret Formation) and the Tournaisian carbonates (Anseremme Group) in the Landelies area (Haine–Sambre–Meuse Overturned Thrust sheets). In this area, a basal unit of massive sandstone, interpreted as the Grès de Watissart (Beugnies, 1973), corresponds to a local facies of the Esneux Formation (see this unit). Eastwards, the Esneux Formation is individualised (map Malonne–Naninne, Delcambre & Pingot, 2017) below the Bois des Mouches formation. The upper part of the formation corresponds to the Comblain-au-Pont Formation whereas the intermediate unit displays the typical facies of the Montfort and Évieux members of the Condroz Formation. In consequence, this name is abandoned in favour of the Condroz Formation.

Booischot Formation – PBI

67See Denayer et al. (2024).

Bon-Mariage Facies

68See Condroz Formation (Montfort Member).

Bosscheveld Formation – PBO

69Origin of name. After the Bosscheveld quarry, north of Maastricht (the Netherlands), where the drilling Kastanjelaan-2 was carried out, Bosscheveld formation (informal unit) in Van Adrichem Boogaert & Kouwe (1994, p. 12).

70Description. The Bosscheveld Formation is typically made of alternations of dark grey to green, argillaceous, often nodular shale, limestone, and grey, sometimes micaceous siltstone and sandstone with fossil plant debris. In the upper part the limestone and shale are dominant and get richer in crinoids, brachiopods and corals.

71Stratotype and sections. Borehole Kastanjelaan-2 (between 400 m and 483.5 m) (Van Adrichem Boogaert & Kouwe, 1994) where the Bosscheveld Formation rests upon the Condroz Formation and is overlain by the Tournaisian Pont d’Arcole Formation.

72Area and lateral variations. Only known from the Campine Basin where the Formation is not laterally continuous, and its occurrence is probably controlled by block tectonics (Laenen, 2003); see Van Adrichem Boogaert & Kouwe (1994) for its distribution in the Netherlands. It lacks in the Booischot borehole. The Bosscheveld Formation is a lateral equivalent of the basal clastic complex known in the Brabant Parautochthon (Higgs et al., 1992); therefore, it is regarded as an equivalent of the Samme Group (at least the Feluy Formation). In the Meuse River valley, north-east of Liège, the Chertal borehole (Graulich, 1975b; Delcambre, in press, b), displays, below 494 m, an alternation of sandstone, limestone and crinoidal limestone at the top, then black-coloured finer material. According to Delcambre (in press, b), these sandstone-carbonate beds may be attributed to the Bosscheveld Formation.

73Thickness. Variable, between 0 and c. 80 m.

74Age. Latest Famennian (Strunian) to Tournaisian (Hastarian). In the Kastanjelaan borehole, Poty (1982) described Conilophyllum priscum (Caninia tregaensis auct.) at 446 m indicating the basal Tournaisian RC1α Subzone, just above the last specimen of Palaeosmilia aquisgranensis (Strunian RC0 Zone). The palynomorphs assemblages indicate the upper Famennian LE Zone to the basal Tournaisian VI Zone (Bless et al., 1981). The Devonian–Carboniferous Boundary is well documented in the Kastanjelaan borehole (Kimpe et al., 1978; Poty, 1986). The layers encountered at the base of the Chertal borehole have been dated to the latest Famennian (Strunian) based on their spore assemblage (Kimpe et al., 1978; Paproth et al., 1983). Conil (1964) assigned these beds to the Famennian and to the extreme base of the Tournaisian, characterised by the presence of ostracods (Cryptophyllus), calcareous algae and foraminifers. The poorly discriminating conodont faunas indicate a pre-Ivorian age (Groessens, 1975).

75Use. Nil.

76Main contributions. Bless et al. (1981), Muchez & Langenaeker (1993), Van Adrichem Boogaert & Kouwe (1994), Langenaeker (2000), Laenen (2003).

Bossière Member – BOS

77See Bovesse Formation.

Boussu-en-Fagne Member – BOU

78See Grands Breux Formation.

Boverie Member – BVR

79See Moulin Liénaux Formation.

Bovesse Formation – BOV

80Origin of name. After the village of Bovesse, Calcaire de Bovesse (…) D8 in Gosselet (1860, p. 93).

81Description. The Bovesse Formation (Fig. 14B) includes shale, limestone and dolostone. It is subdivided into three members.

82The lower Bossière Member – BOS (Assise de Bossières in Conseil de Direction de la Carte, 1896, p. 54) comprises greyish to grey shale that includes siliceous to sandy dolomitic beds varying between few centimetres and one decimetre in thickness. This shale locally incorporates some haematitic oolites. A thin conglomeratic horizon is locally present at the base (Delcambre & Pingot, 2008).

83The middle Combreuil Member – CBR (Membre de Combreuil in Hennebert & Eggermont, 2002, p. 21) is made of massive, coarse-grained blond-grey to pinkish dolostone, usually cavernous, that alternates with shale, dolomitic shale and argillaceous dolostone. Where the dolomitization is moderate, the rock is rich in rugose and tabulate corals and sometimes brachiopods, but where it is more pronounced, only the ghosts of fossils are visible. This member is discontinuous laterally and forms several hundred metres long and up to 20 m thick lenses embedded into the overlying Champ du Fau Member. Delcambre & Pingot (2008) suggested that these lenses may correspond to dolomitized bioherms.

84The upper Champ du Fau Member – CHF (Membre du Champ du Fau in Hennebert & Eggermont, 2002, p. 21) includes grey shale with few beds containing brachiopods (atrypides, spiriferides, etc.). The shale tends to get richer in limestone (nodules, or even thin beds) in the vicinity of the dolostone lenses of the Combreuil Member (Delcambre & Pingot, 2008).

85Stratotype and sections. Three sections, investigated by Coen-Aubert & Lacroix (1985, fig. 2: outcrops nos. 1–3) and located east of Huccorgne in the Mehaigne River valley, were selected by Lacroix (1999b) as the composite parastratotype of the Formation. Indeed, there is no reference section anymore in the Bovesse area, situated 8 km to the northwest of Namur; only a few scattered small outcrops remain around this village according to Delcambre & Pingot (2015). However, Delcambre & Pingot (2014a) pointed out that the Bovesse Formation as exposed in the Mehaigne River valley differs from the historical type area and the Orneau River valley because, in both latter areas, shale predominates on carbonate facies; moreover, oolitic ironstone horizons of the Bossière Member are absent at Huccorgne (Delcambre & Pingot, 2014a).

86Area and lateral variations. The Bovesse Formation is recognised in the Brabant Parautochthon, from the Dendre River to the Mehaigne River valleys, around Huccorgne (Delcambre & Pingot, 2014a). It was also reported from the western part of the Brabant Parautochthon, in the Tournai and Leuze boreholes, where thicknesses of 396 m (Tournai) and 318 m (Leuze) were mentioned by Coen-Aubert et al. (1981), as well as in the Nieuwkerke-De Seule borehole (Tourneur et al., 1989; Streel et al., 2021), but the absence of dolostone means that the rocks encountered there cannot be attributed definitely to the Bovesse Formation. These deposits are also similar to those included in the Frasnian Beaulieu Formation from the nearby Boulonnais area in France (Tourneur et al., 1989).

87In the Mehaigne River valley, the Caledonian rocks of the Brabant Inlier are overlain by a few metres of terrigenous and continental deposits that were ascribed to the Bovesse Formation by Asselberghs (1936) and Lacroix (1999b). Coen-Aubert & Lacroix (1985) and Delcambre & Pingot (2014a) logically assigned these siliciclastic rocks to the Givetian Bois de Bordeaux Group (see Denayer et al., 2024). However, the typical shale of the Bossière Member is lacking at Huccorgne, and the Formation starts directly with the Combreuil Member consisting of two dolomitic units separated by shale and bedded limestone with some horizons rich in fasciculate rugose corals (Disphyllum preslense, Fig. 8G).

88Thickness. From west to east: 80–90 m at Ronquières (i.e. 15–25 m for the Bovesse, 35–45 m for the Combreuil, and 10–45 m for the Champ du Fau members, respectively, after Legrand, 1967; Hennebert & Eggermont, 2002), c. 85 m in the Orneau River valley (Delcambre & Pingot, 2008), c. 80 m north of Namur and at Huccorgne (Delcambre & Pingot, 2014a, 2015).

89Age. Early Frasnian. There is no conodont data from surface outcrops. Ancyrodella binodosa is known from the so-called Bossière Member in the Leuze borehole (Coen-Aubert et al., 1981) whereas A. rotundiloba, which is the index conodont for the base of the Frasnian (see section 3), is reported from the unit in the Tournai borehole by Magne (1964) (see remarks above concerning Coen-Aubert et al.’s (1981) doubtful attribution of the rocks yielding the conodonts to the Bovesse Formation). The solitary rugose coral Macgeea rozkowskae is reported from beds above the first dolostone horizon at Huccorgne (Coen-Aubert & Lacroix, 1985). The spiriferide brachiopod succession was presented by Sartenaer (1982, 1999a), including notably Eodmitria oblivialis oblivialis (Pl. 1.J) and E. oblivialis grandis (Pl. 1.K) that are also known from the Nismes Formation.

90Use. Locally used as building stone.

91Main contributions. Stainier (1892), Malaise (1903), Asselberghs (1912, 1936), Vandamme (1981), Coen-Aubert & Lacroix (1985), Lacroix (1999b).

Brayelles Dolomitic Facies

92See Pont de la Folle Formation (Fontaine Samart Member).

Chalon Member – CHA

93See Moulin Liénaux Formation.

Champ Broquet formation

94Disused informal unit; replaced by the Marche-en-Famenne Formation.

Champ du Fau Member – CHF

95See Bovesse Formation.

Ciney Member – CIN

96See Condroz Formation.

Citadelle de Huy Facies

97See Condroz Formation (Montfort Member).

Comblain-au-Pont Formation – CBP

98Origin of name. After the village of Comblain-au-Pont in the Ourthe River valley (Fa3f Calcaire de Comblain-au-Pont à grandes tiges d’encrines, à Phacops granulosus in Mourlon, 1882, p. 520).

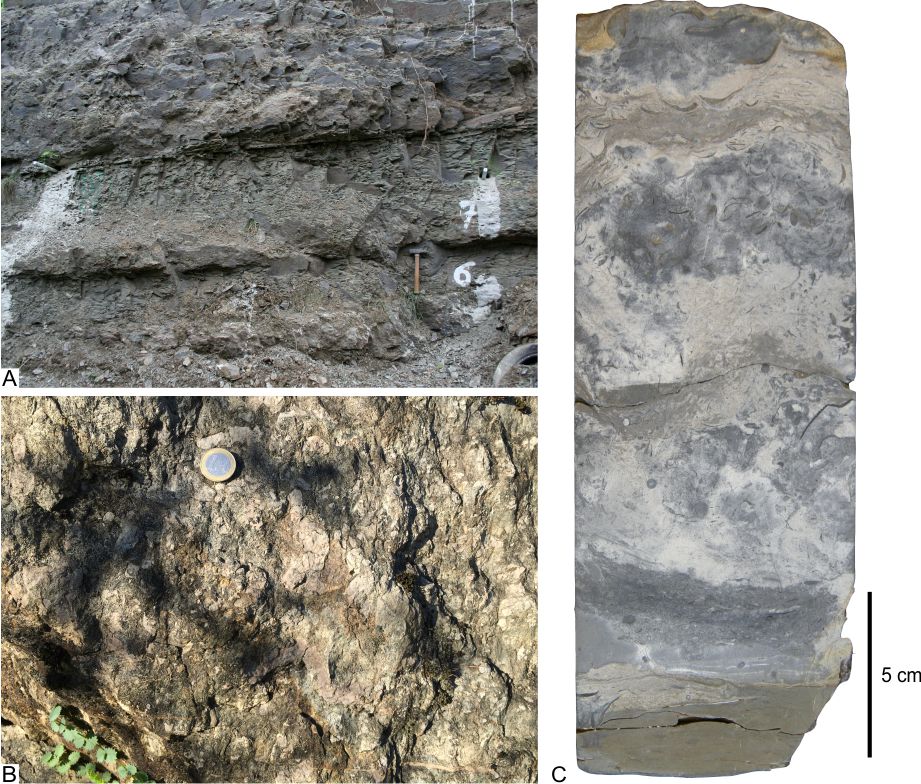

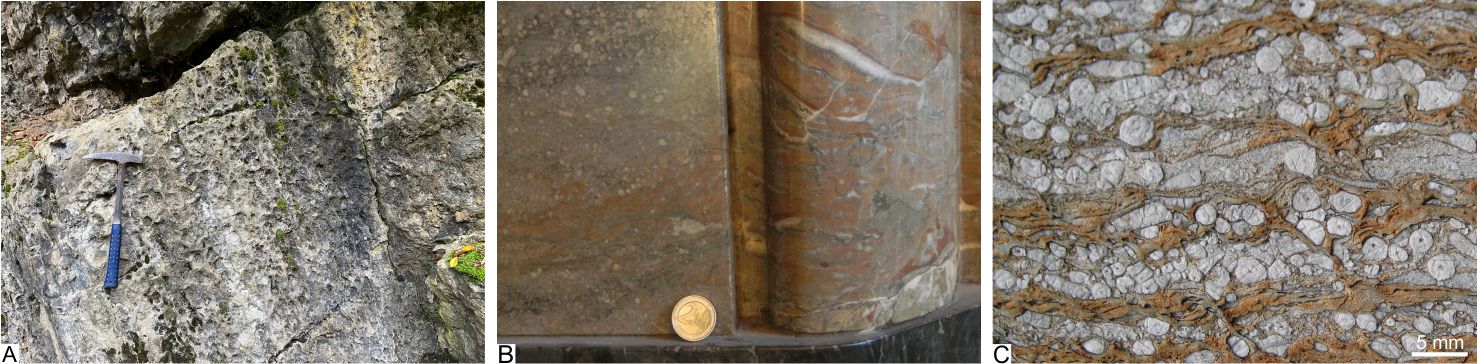

99Description. The Comblain-au-Pont Formation (Fig. 15) is typically composed of an alternation of siliciclastic and limestone arranged in couplets that correspond to climatic cycles (Poty, 2016). The base is defined by the first bed of crinoidal limestone overlying the siltstone and sandstone of the Condroz Formation. In some sections (Chanxhe (Fig. 15A), Hastière), a thin horizon with limestone clasts occurs, highlighting the base of this transgressive unit. The lower part of the Formation is still dominated by sandstone and siltstone, but the latter are not arkosic and micaceous anymore contrary to the underlying Ciney and Évieux members of the Condroz Formation. Limestone beds increase in frequency and thickness upwards whereas the sandstone facies disappear progressively. The upper part is dominated by the coarse-grained crinoidal and bioclastic limestone usually rich in macrofossils (solitary rugose corals, stromatoporoids, brachiopods, trilobites). Several fossil-rich horizons were named premier biostrome, second biostrome, and biostrome principal by Conil (1964) but genuine biostromes (Fig. 15B) are only known from the Vesdre area (Dolhain Facies, Formation de Dolhain in Laloux et al., 1996b, p. 36) where the upper part of the Formation is massive and locally dolomitized.

100The Comblain-au-Pont Formation shows an increase in offshore features towards the south and west and passes to the Etrœungt Formation in the western part of the Dinant Synclinorium. Therefore, the successions exposed notably in Anseremme and Gendron-Celles sections are rather different from that exposed in the type locality, notably through an increase of the limestone proportion. In this area, these rocks were often designated under the name Calcaire d’Etrœungt (e.g. Conil, 1964; Bouckaert et al., 1974b), but their facies are not those typical of that formation either. They are thus distinct from the usual facies of the Comblain-au-Pont and are designated here as the Lesse Facies (Fig. 15C).

101The Comblain-au-Pont Formation witnessed the re-installation of open-marine conditions at the end of the Famennian. Its upper boundary corresponds to the last bed of shale below the massive limestone basal bed of the overlying Hastière Formation.

102Stratotype and sections. The historical type section situated along the road between Esneux and Comblain-au-Pont, along the Ourthe River, is partly overgrown and tectonically perturbed (Bellière, 2015). The renowned Chanxhe I section exposes particularly well the Formation, except its top, also removed by a fault. In the southern part of the Dinant Synclinorium, the Anseremme railway section exposes the entire formation, but with the typical Lesse Facies made of shale–limestone cycles. The Dolhain Facies is exposed in the eponymous locality, along the Vesdre River north of the Dolhain–Limbourg station.

103Area and lateral variations. The Formation is developed in the Dinant Synclinorium between the Ourthe River and the Eau d’Heure River valleys where it becomes progressively poorer in sandstone and richer in shale. It passes gradually to the Etrœungt Formation in the south-western part of the Dinant Synclinorium, west of Walcourt. The Dolhain Facies is known in the Vesdre River valley. Eastwards, in Germany, the Comblain-au-Pont Formation is named Etrœungt-Formation (ex Über Kohlenkalk) (Deutsche Stratigraphische Kommission, 2016).

104Thickness. c. 100 m in the Meuse River valley, 70 m in the Ourthe River valley (Conil, 1968).

105Age. Latest Famennian (Strunian). The Comblain-au-Pont Formation almost coincides with the Strunian substage as defined by Streel et al. (2006). In the type area, the first marine limestone marking its lower boundary yielded the first Bispathodus ultimus indicating the base of the former upper expansa conodont zone and the first Quasiendothyra kobeitusana indicating the DFZ7 foraminifer Zone, along with the first rugose corals indicating the RC0β Subzone (bed 111 of the Chanxhe section; Denayer et al., 2021). The spore Retispora lepidophyta, marker of the LL Palynozone, occurs in bed 92, i.e. 8 m below the first limestone with B. ultimus (Maziane et al., 1999). In more distal settings (Anseremme section), the appearances of the markers are more spread out, with the first B. ultimus occurring c. 8 m below the first Q. kobeitusana, in the Strunien gréseux sensu Conil (1964), i.e. below the base of the Comblain-au-Pont Formation. The typical assemblage with Campophyllum sp., Bounophyllum praecursor and Palaeosmilia aquisgranensis (Fig. 11A, C, E) characterises the RC0 Zone that starts near the base of the Formation. Although largely unrevised, the brachiopod fauna of the Comblain-au-Pont Formation includes some productidines such as Mesoplica nigeraeformis (Pl. 4.Z) and Spinocarinifera aff. lotzi (Pl. 4.AA), but also three typical Strunian species, namely the rhynchonellide Araratella moresnetensis (Pl. 4.BB) and the spiriferides Prospira struniana (Pl. 4.CC) and Sphenospira julii (Pl. 4.DD) (Sartenaer & Plodowski, 1975; Legrand-Blain, 1991; Mottequin & Brice, 2016; Denayer et al., 2021); both latter species are also known from the Etrœungt Formation. Mourlon (1882) used the last phacopid trilobites to characterise this unit, i.e. Omegops accipitrinus and O. maretiolensis (Pl. 4.EE) (Richter & Richter, 1933; Crônier et al., 2025). The top of the Formation is still Devonian-aged (DFZ7 and LL zones, and RC0β Subzone) as the Devonian–Carboniferous boundary is situated within the first bed of the overlying Hastière Formation.

106Use. The limestone was locally exploited in small quarries as building stone, notably in the Vesdre area (Laloux et al., 1996a, 1996b).

107Main contributions. Streel (1966), Conil (1968), Bouckaert et al. (1970), Paproth & Streel (1970), Becker et al. (1974), Bouckaert et al. (1978), Van Steenwinkel (1984, 1990), Conil et al. (1986), Dreesen et al. (1986b), Poty (1999, 2016), Maziane et al. (2002), Poty et al. (2011), Prestianni et al. (2016), Denayer et al. (2016, 2021).

Figure 15. Illustration of the Comblain-au-Pont Formation. A. Typical alternation of siliciclastic and limestone beds. Chanxhe I section. B. First and second stromatoporoid biostromes of the Dolhain Facies. Trooz quarry (from Poty et al., 2011). C. Alternations of the thick beds of limestone and shale of the Lesse Facies. Anseremme railway section.

Comblain-la-Tour Member – CLT

108See Condroz Formation.

Combreuil Member – CBR

109See Bovesse Formation.

Condroz Formation – CDZ

110Origin of name. Psammites jaunâtres qui recouvrent, entre autres, les plateaux de la contrée nommée Condros, the typical Famennian sandstone in the Condroz area, introduced by d’Omalius d’Halloy (1839, p. 448), and psammites du Condros in d’Omalius d’Halloy (1853, p. 555, footnote).