- Accueil

- Volume 28 (2025)

- number 3-4

- Lithofacies and depositional settings of the Coniacian–Campanian Chalks in the Mons Basin (Belgium)

Visualisation(s): 599 (20 ULiège)

Téléchargement(s): 277 (1 ULiège)

Lithofacies and depositional settings of the Coniacian–Campanian Chalks in the Mons Basin (Belgium)

Abstract

Three drill holes in the Mons Basin yield together 350 m of Coniacian to Campanian chalk cores. Detailed geological logging was conducted on the well-known Trivières Chalk, Saint-Vaast Chalk, and Maisières Chalk formations. A thorough sedimentological characterization was performed, from macrofacies to SEM microtexture. Petrographic observations and geochemical analysis indicate eogenetic calcite cementation and phosphatization in two benchmark levels, already known for their high glaucony content, namely in the Trivières Chalk Formation and the Maisières Chalk Formation. Upwelling currents, prevalent during the Late Cretaceous, are likely the source of the phosphates, and the cause of reduced sedimentation rates. Strong anoxic currents resulted in the formation of hardgrounds, the development of glaucony pellets and pyrite formation within shallow subtidal sediments. Multiple conglomeratic chalk intervals were identified in the Trivières Chalk Formation. They likely result from local sediment destabilization due to extensional tectonic activity. Moreover, the identification of deformation bands attests to synsedimentary tectonic activity within the basin. Overall, this research unravels various phenomena, including marine currents, sea-level fluctuations, and tectonic activity, that influenced chalk deposition in the Mons Basin. This research enables enhanced comprehension and forecasting of the heterogeneities in chalk and its spatial variability.

Table des matières

1. Introduction

1Chalk, a characteristic deposit of the Late Cretaceous in Northwestern Europe, holds significant economic importance. It serves as a raw material in quicklime and cement production, acts as a major hydrocarbon reservoir in the North Sea, and is the primary aquifer of Northwestern Europe. Historically, chalk has been classified as a fine-grained, coccolith-dominated white carbonate, deposited by settling in deeper water. However, in the 1990s, some authors suggested that chalk was also deposited in environments ranging from open shelf-sea (e.g. in Danish cliff outcrops) to deeper settings under the influence of gravity-driven currents (e.g. Central North Sea) (Kennedy, 1987; Surlyk, 1997; Ineson et al., 2005). In some studies, the depositional environment and diagenetic history of the chalk based on sedimentological logging and microfacies observations were reconstructed (Lasseur et al., 2009; Mortimore et al., 2017; Faÿ-Gomord et al., 2018; Ineson et al., 2022). In the Mons Basin, chalk was deposited in the Boreal realm. Its cumulated thickness was estimated to vary around 300 m (Baele et al., 2012). The lithostratigraphy of the chalk in the Mons Basin is well defined, with main subdivisions identified by Briart & Cornet (1880) and Marlière (1967), and recently redefined by Robaszynski et al. (2001). Most available studies focus on white Campanian chalk formations. Richard et al. (2005) examined the sea-level changes in the Campanian Boreal Sea by combining geochemical data with petrophysical measurements and petrographic observations. The phosphatic chalks’ physical properties (Robaszynski & Martin, 1988; Georgieva et al., 2023) as well as synsedimentary faulting controlling the deposition of the Maastrichtian phosphatic chalk were thoroughly studied by Jarvis (1980, 1992, 2006), Vandycke et al. (1991) and Mortimore et al. (2017). However, there is limited published work on the chalks ranging from Coniacian to lower Campanian, which includes the Maisières Chalk, Saint-Vaast Chalk, and Trivières Chalk formations. The quarry at Saint-Vaast, where the Craie de Saint-Vaast was originally defined, has been filled and there are currently no good outcrops exposing this Formation.

2In this study, we had access to three boreholes from the northeastern part of the Mons Basin, allowing to study the entire succession from the Coniacian (upper Maisières Chalk Formation) to the lower Campanian (base of Obourg Chalk Formation). Previously, mechanical tests and fracture logging were carried out on these cores by Descamps et al. (2020). Complementary to this engineering approach, an in-depth geological characterization is completed as part of this study. Detailed logging was performed, and thorough characterization of the chalk facies at different scales (macrofacies, microfacies, and microtexture) provides new insight into geological setting of the initial chalk deposits within the Mons Basin (Philip & Floquet, 2000; Robaszynski et al., 2001).

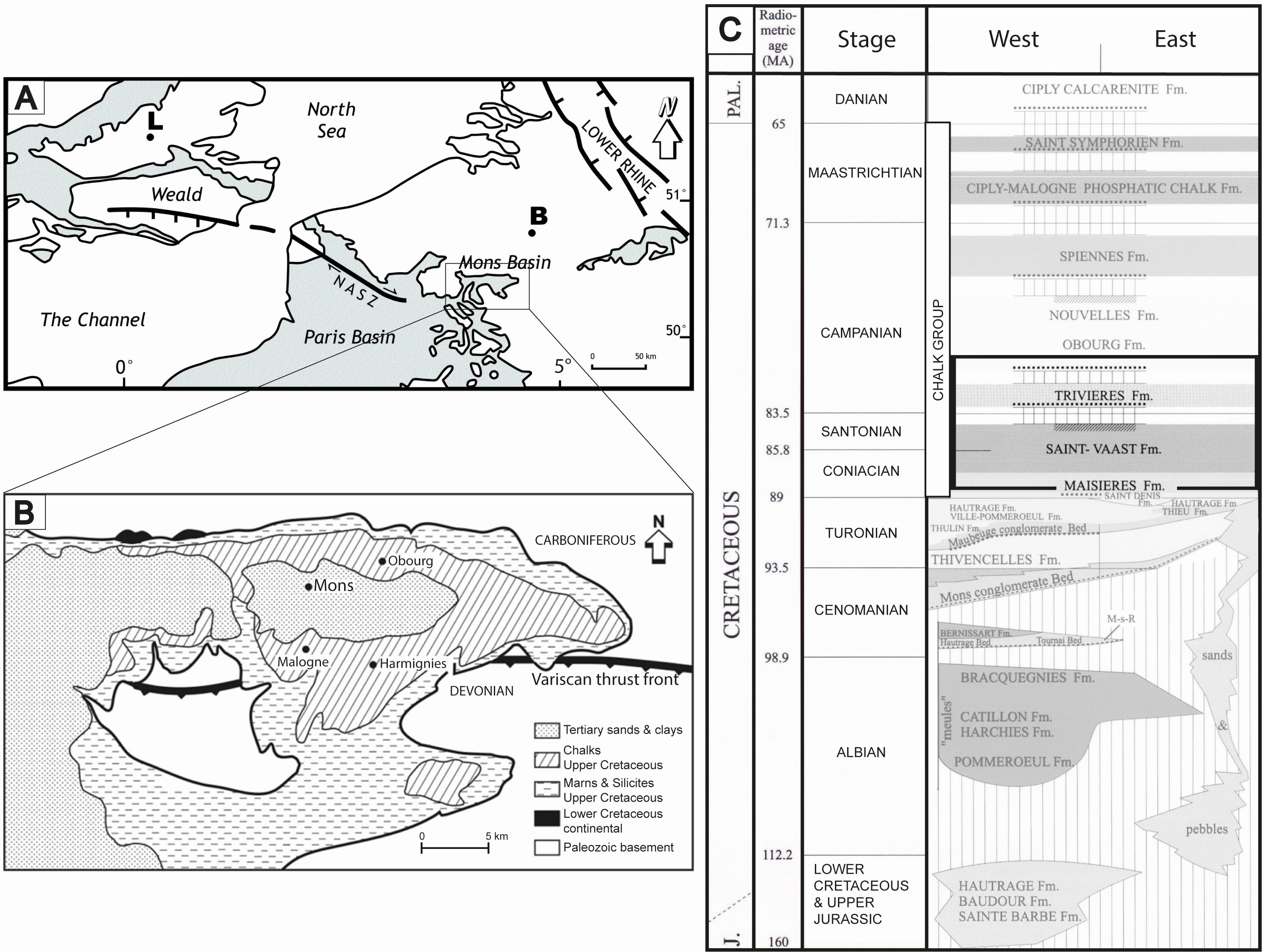

2. Geological context

3The Mons Basin is located in south-western Belgium, close to the French border. This elongated basin (40 km long, 15 km wide) is filled with sediments ranging from Wealden fluviolacustrine deposits (Early Cretaceous) to Eocene marine deposits (Marlière, 1970; Baele et al., 2012). The progressive tectonic subsidence recorded from the Early Cretaceous till the end of the Cretaceous (Dupuis & Vandycke, 1989) allowed a continuous stratigraphic accumulation of sediments in this Basin. Our study area is in the northern part of the Mons Basin, which consists of a semi-continuous 300-m-thick pile of Meso-Cenozoic sediments that accumulated in a small but actively subsiding area, where synsedimentary tectonic extension was recorded throughout the whole sedimentary succession (Vandycke et al., 1991; Vandycke, 2010). The Mons Basin is defined as a transitional area, located in between main structural elements of North-western Europe, such as the North Sea and Paris Basin, the Rhine Graben as well as the English Channel. It is located at the intersection of major crustal features, such as the North Artois Shear Zone and the thrust Variscan front (Colbeaux, 1974). From the Early Cretaceous until the Turonian, the Mons Basin was limited by the Rhenish Massif to the ENE (Philip & Floquet, 2000). It is traditionally considered as an eastern extension of the Paris Basin (Thiry et al., 2006), while its deposits are also correlated with those deposited in the east of Belgium (Robaszynski et al., 2001). At the beginning of the Cretaceous, the opening of the Atlantic Ocean was initiated, and the Proto-Tethys developed (Ziegler, 1988) (Fig. 1A). The formation of the Paris Basin began with the development of large deltaic paleovalleys that supplied the Basin with fluvial sediments. An east-west Early Cretaceous paleovalley was identified in the northern part of the Mons Basin, indicative of a river that used to flow westward into the Paris Basin (Spagna et al., 2012). Eustatic transgressive pulses, during the Albian and Cenomanian, led to siliciclastic-carbonate deposition, followed by marls during the Turonian maximum flooding. After a short fall in sea level, an important transgressive sequence was deposited, leading to the sedimentation of a chalk sequence (Fig. 1B). Chalks are prevalent in the Mons Basin from the Coniacian to Maastrichtian stages (Robaszynski et al., 2001). Detailed lithostratigraphic studies of the Mons Basin have been carried out by several authors since the 19th century (Cornet & Briart, 1866; Cornet, 1922; Marlière, 1970; Dupuis & Robaszynski, 1986; Robaszynski et al., 2001). Based on the observations and available literature, the chalk was dated from the Coniacian–Campanian, and is divided into four geological formations (Fig. 1C):

4(1) Obourg Chalk Formation, consisting of fine white chalk, was dated to the early late Campanian period using various cephalopods, including Belemnitella mucronata, Patagiosites stobaei, Glyptoxoceras retrorsum, and Baculites aquilaensis. Additionally, brachiopods such as Carneithyris carne and “Cretirhynchia” octoplicata were used. Echinoids, including Echinocorys cf. ovata, E. gibba, Micraster schroederi, and M. stolleyi, were also utilized. Lastly, foraminifera like Bolivinoides decoratus, Gavelinella monterelensis, Stensioeina pommerana, and Globorotalites michelinianus were used in the dating process (Robaszynski & Christensen, 1989; Christensen, 1999).

5(2) Trivières Chalk Formation is composed of a white to gray marly chalk without flints. The Trivières Chalk Formation was dated to the late early Campanian period based on cephalopods such as Gonioteuthis quadrata, Belemnitella gr. mucronata, and Scaphites gibbus. Bivalves like Oxytoma tenuicostata and Endocostea baltica were also found. Additionally, the presence of echinoids, specifically Echinocorys gr. ovata and Micraster schroederi, further supports this dating (Godfriaux & Sigal, 1969).

6(3) Saint-Vaast Chalk Formation consists of white chalk with layers of clay and flint in its lower part. The Coniacian age is attributed to the lower section of the Saint-Vaast Chalk Formation, as evidenced by the presence of Micraster decipiens, Volviceramus involutus, and the foraminifer Dicarinella gr. concavata. Conversely, the upper section of the Saint-Vaast Chalk Formation is identified as being of the Santonian age, indicated by the presence of Micraster coranguinum, Actinocamax verus, Gibbaster belgicus, Sphenoceramus digitatus, and foraminifers such as Stensioeina exsculpta gracilis, Gavelinella clementiana, and Bolivinoides strigillatus (Godfriaux & Sigal, 1969).

7(4) Maisières Chalk Formation is composed of glauconitic, granular and calcarenitic green chalk, which marks the lower limit of our investigations. The Maisieres Formation has been dated to the Coniacian age based on the presence of planktonic foraminifers Dicarinella gr. concavata and Globotruncana linneiana, oysters Hyotissa semiplana and Gryphaeostrea canaliculata, and the brachiopod “Cretirhynchia” plicatilis (Moorkens, 1969; Godfriaux & Sigal, 1969). The highly glauconitic formation consists of a layer 0.5 to 2 m-thick, marking the lower, transgressive sequence of the chalk deposits.

8During the Coniacian/Santonian, the Mons Basin was located at the frontstage of the Rhenish Massif, in waters that were still relatively shallow compared to the rest of the Anglo-Paris Basin. The Chalk Sea was, however, already connected to the Atlantic Ocean, which was still actively opening at that time. The sea level did not submerge the Rhenish Massif until the Campanian period, associated with the deposition of the white chalk of the Obourg Chalk Formation (Robaszynski & Christensen, 1989).

Figure 1. A. Location of the Mons Basin in the Chalk district (gray) in NW Europe. Abbreviations: B, Brussels; L, London; NASZ, North Artois Shear Zone. Modified from Vandycke & Spagna (2012). B. Schematic geological map of the Mons Basin with the location of Obourg (after Robaszynski & Martin, 1988). C. Stratigraphy of the Cretaceous deposits within the Mons Basin, with the section framed in black (after Robaszynski et al., 2001). Abbreviations: J, Jurassic, Pal., Paleogene.

3. Methodology

3.1. Core drilling and logging

3.1.1. Drilling operations

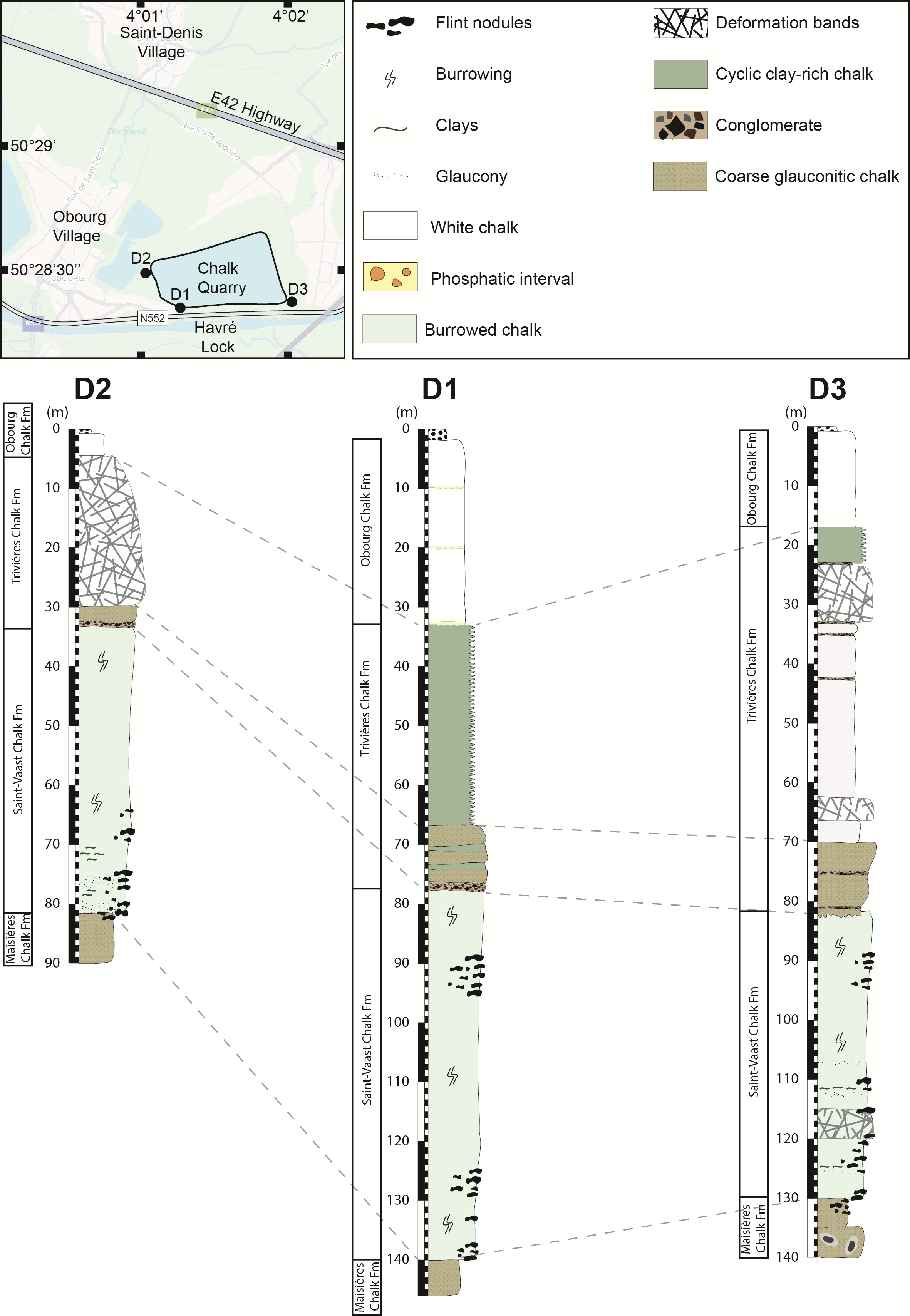

9Three drill holes (D1, D2, and D3) were cored by SMET GWT Europe in the Holcim Obourg Quarry. The boreholes were drilled to assess the detailed geology and geomechanical properties of the chalk from the surface down to a depth of approximately 150 m, below the currently quarried layers. The quarry is located between Obourg village to the west and Ville-sur-Haine village to the east, along the N552 road (commonly referred to as the “industrial road”), facing the Havré lock on the Centre Canal, and is bordered to the north by the Bois de la Vigne forest. The exact coordinates of the drilling locations are D1 at 50°28’22”N, 4°01’27”E; D2 at 50°28’30”N, 4°01’05”E; and D3 at 50°28’21”N, 4°02’00”E. As shown in Figure 2, D2 is located approximately 300 m north of both D1 and D3, while D3 lies about 600 m east of D1 and 900 m east of D2.

10The lengths of the cores from drill holes 1, 2 and 3 are 146 m, 89 m and 139 m, respectively. In total, approximately 374 m of chalk were extracted, either with an auger, SQ (146 mm) or PQ (122 mm) size core barrel. The core diameters are 8 or 10 cm.

Figure 2. Geographical location of the three drillings within the Obourg quarry, and correlation of the drill holes. Abbreviation: Fm, Formation.

3.1.2. Geological logging

11Geological core logging was performed on saw-cut cores in order to access fresh, undisturbed material and study the rock characteristics and the different deformation features. In most of the boxes, the core material remained cohesive. However, it has been broken down into rubble locally, which is a consequence of both intense fracturing and freeze-thaw cycles in the upper 40 m, making the geological observations more difficult. Each fracture, regardless of whether drilling-induced or natural, was recorded in the comprehensive logs of each core (Descamps et al., 2020). Figure 2 illustrates the three synthetic logs, pinpointing their respective locations within the quarry. It also presents their correlations, which are determined based on the key lithological intervals as defined by Robaszynski et al. (2001). Within the Mons Basin, biostratigraphic studies and lithological characterizations of the Coniacian to Campanian formations primarily rely on outcrops and core samples from the southern region of the basin. However, despite variations in the thickness of each formation, the lithological characteristics remain identifiable across the Mons Basin. In this study, marker layers and lithological changes were identified across all three boreholes and subsequently correlated (Fig. 2). The transition between the glauconitic chalk of Maisières Chalk Formation and the marly facies of Saint-Vaast Chalk Formation, the base of the Trivières Chalk Formation characterized by a coarse interval are recognized in all three boreholes and used for correlation. The rapid transition from the marly Trivières Chalk Formation to the white chalk of the Obourg Chalk Formation provides another correlation point for the three boreholes. The phosphatic conglomerate at the base of the Obourg Chalk Formation, as described by Robaszynski et al. (2001), is present in two of the boreholes and is also used for stratigraphic correlations.

12Note that in this study, the term “glaucony” is used to describe clayey sedimentary grains found in chalk. The interchangeable use of “glauconite” and “glaucony” in literature leads to confusion. According to Velde & Odin (1975), the term “glauconite” should be strictly used to denote an iron-potassium hydrous phyllosilicate mineral. In contrast, “glaucony” is a broader term that refers to the green marine clay facies. Therefore, through core and petrographic descriptions, it is possible to identify grains of glaucony, rather than glauconite.

3.2. Mineralogy

13Mineralogical analysis of selected samples was performed using X-ray diffraction. Eleven samples were analyzed: eight from D1, one from D2 and two from D3. Each sample was first dried in an oven at 60 °C. After drying, a part of the samples was milled in a wet milling device. The samples were then handled in such a way that any preferred orientation of any mineral in the sample was avoided. They were then loaded into an X-ray diffraction (XRD) sample holder and analyzed using Cu-K-α radiation (Mendenhall et al., 2017). The subsequent quantification was performed by the Rietveld method (Young, 1993).

3.3. Thin sections

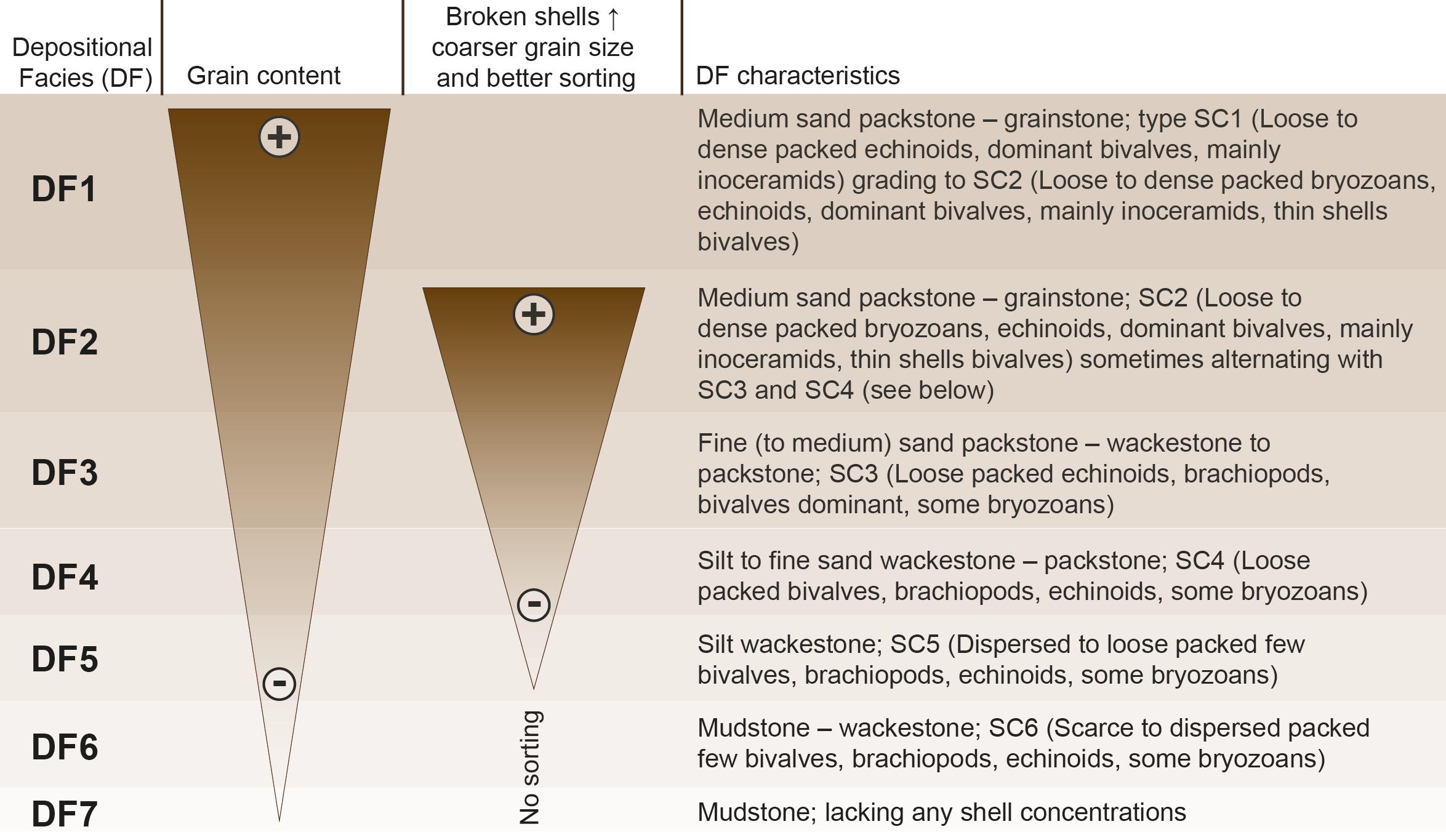

14In the framework of this study, 29 standard 30 µm-thick thin sections were prepared. Thin sections were impregnated under vacuum conditions with a fluorescence epoxy resin to highlight the porous network. The sediment texture was described based on the Dunham (1962) classification of limestones, based on the fraction of grains (>20 µm). JMicroVision Image analysis (Roduit, 2008) on natural transmitted light thin section images was used to quantify the proportion of grains present in the micritic matrix. The depositional facies (DF) of each sample was determined using both macrofacies, Dunham texture (Dunham, 1962), fauna content and the sedimentary features, as described by Lasseur et al. (2009), and modified by Faÿ-Gomord et al. (2018). Seven depositional facies (DF1 to DF7) were identified by the latter authors, primarily based on shell concentration and grain content, which includes bioclasts and lithoclasts. Figure 3 provides a concise summary of the characteristics of each DF, as initially defined by Lasseur et al. (2009). The depositional environments were then inferred by using both the depositional facies and the properties of hiatal surfaces.

Figure 3. Depositional facies (DF) classification of Lasseur et al. (2009), also based on hiatal surfaces and shell concentrations (SC).

3.4. SEM analysis

15Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) on fresh surfaces of the samples was used to observe non-carbonate minerals, to identify microporosity and to study microtextural features. Investigations were carried out on a TESCAN MIRA field emission microscope equipped with an energy dispersive spectrometer (EDS) with image magnifications from 1,000 to 20,000 times. EDX mapping was performed using Aztec software. Throughout this paper, the term “microtexture” describes the texture of the chalk matrix, as observed under SEM, while “texture” always refers to the Dunham sedimentary classification.

4. Results

4.1. Lithological logging

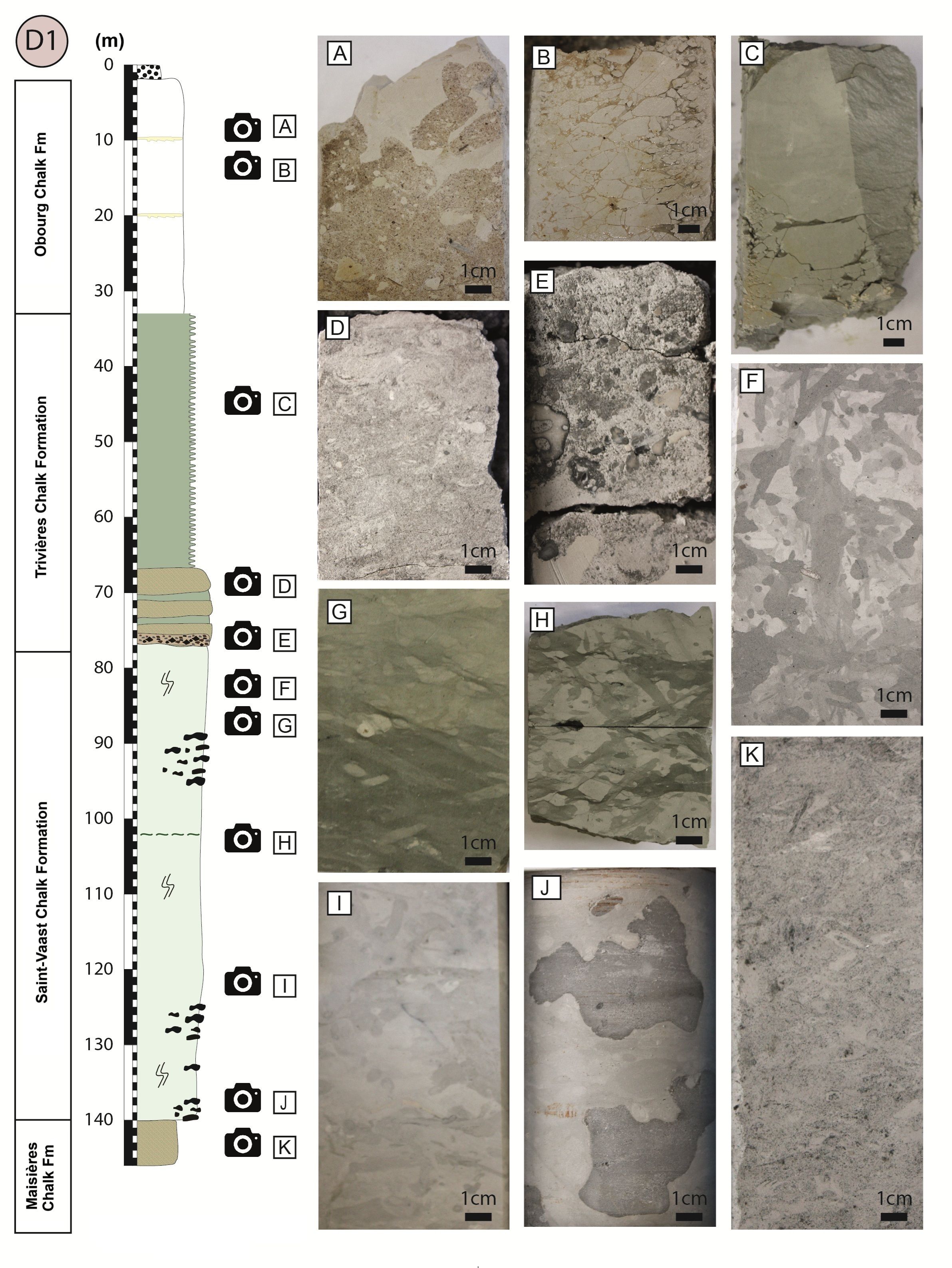

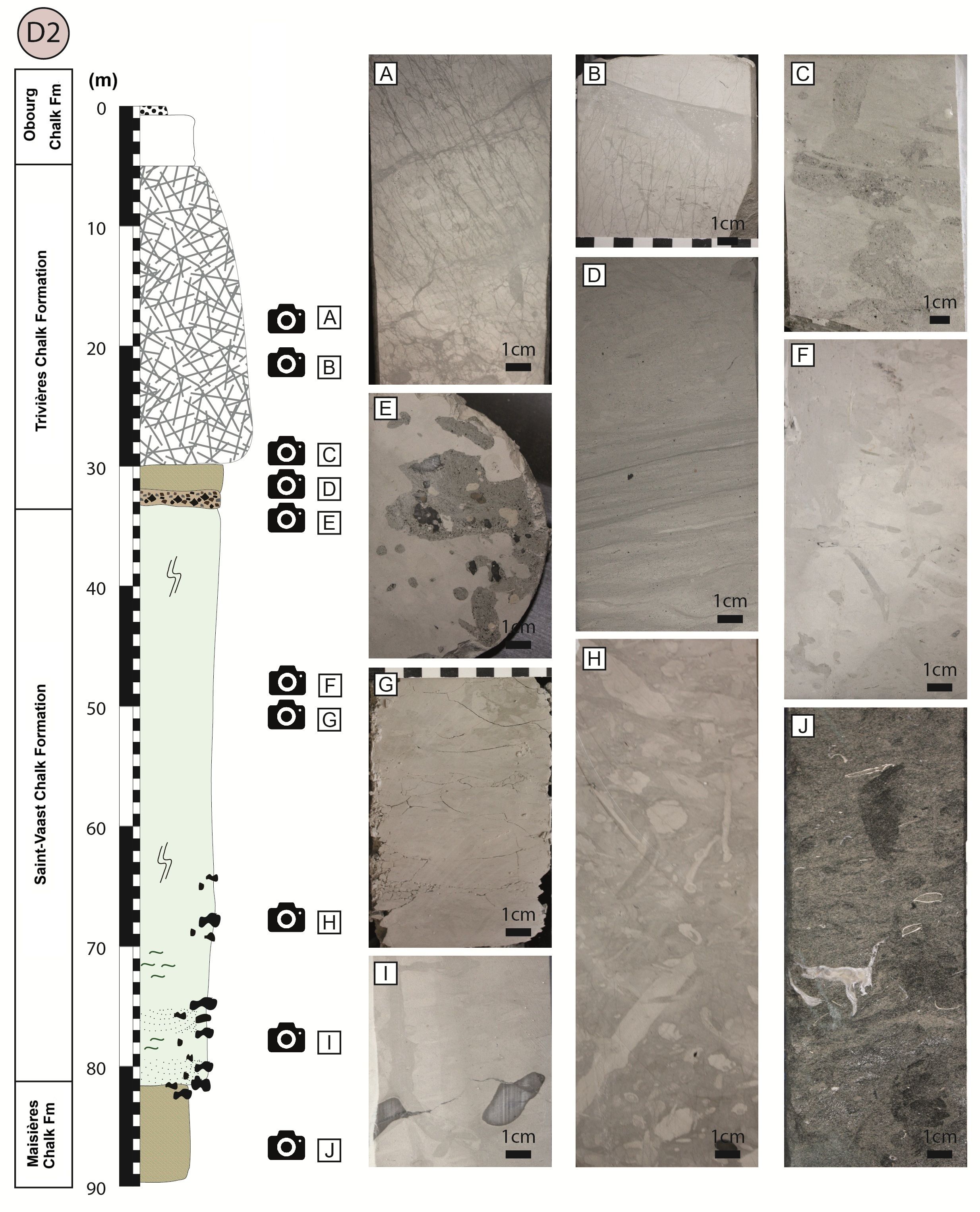

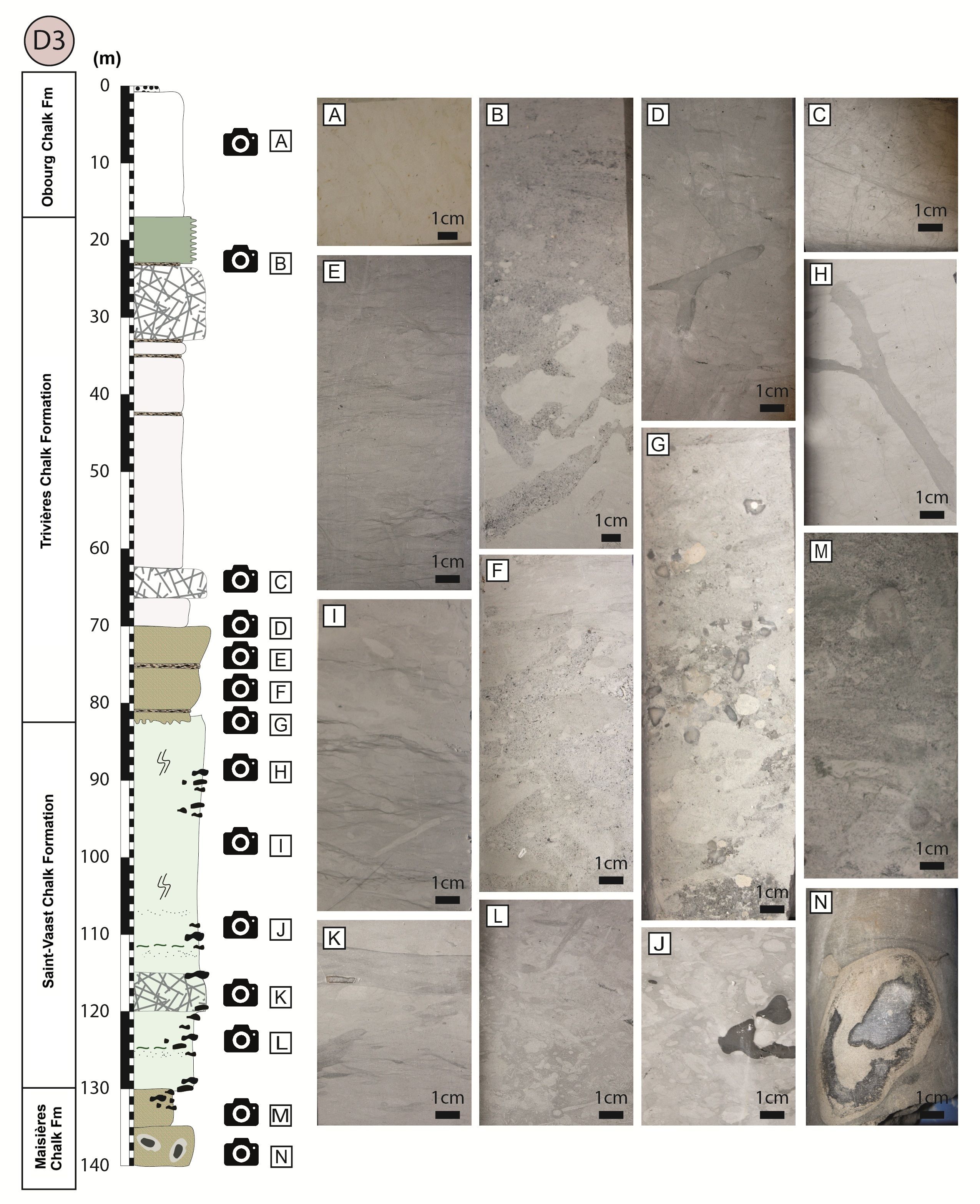

16Comprehensive geological logging was carefully conducted on all drill holes, and synthetic logs are depicted in Figures 4, 5 and 6. The synthetic logs in Descamps et al. (2020) were divided into six chalk lithotypes: i.e. white chalk, gray chalk, dark gray chalk, marly chalk, coarse glauconitic chalk, and conglomerate (alternatively referred to as conglomeratic chalk). These lithotypes were characterized based on several attributes easily identifiable in the quarry, including color (white, gray, dark gray), texture (marly), and grain size (coarse, conglomerate) of the chalk. From an engineering point of view, a subsequent correlation between petrophysical and geomechanical properties of the material was performed (Descamps et al., 2020). From a sedimentological perspective, geological units can be identified, aligning well with the stratigraphic formations previously defined in literature (Robaszynski et al., 2001). The Obourg Chalk (Fig. 4A–B, Fig. 6A), Trivières Chalk (Fig. 4C–E, Fig. 5A–E, Fig. 6B–G), Saint-Vaast Chalk (Fig. 4F–J, Fig. 5F–I, Fig. 6H–L) and Maisières Chalk (Fig. 4K, Fig. 5J, Fig. 6M–N) formations are clearly identified, which will be described from older to younger deposits (see below). However, the lower part of the Trivières Chalk Formation includes a very distinctive interval of coarse glauconitic chalk, with conglomeratic layers, which will be described separately.

Figure 4. Schematic geological logging of Drill hole 1 and its characteristic lithofacies. (A) phosphatic breccia, (B) white chalk affected by freeze-thaw weathering, (C) cyclic chalk couplet indurated at the top and marly at the base, (D) glauconitic chalk, (E) conglomeratic chalk layer, (F) intense burrowing of Saint-Vaast Chalk Formation by Thalassinoides, (G) bioturbations in a clay-rich interval, (H) flaser structures attesting to cyclic bottom currents, (I) bioturbations of Saint-Vaast Chalk Formation, (J) chert nodules, (K) Glauconitic Maisières Chalk Formation. Abbreviation: Fm, Formation.

Figure 5. Schematic geological logging of Drill hole 2 and its characteristic lithofacies. (A) deformation bands in anastomosing swarms, (B) deformation bands terminating on a thin clay-rich layer, (C) intensively burrowed glauconitic chalk, (D) clay laminations in argillaceous chalk, (E) conglomeratic chalk layer, (F) typical bioturbated Saint-Vaast Chalk Formation, (G) bioturbated and weathered gray chalk, (H) bioturbated chalk with a nodular texture, (I) chert nodules, (J) Glauconitic Maisières Chalk Formation. Abbreviation: Fm, Formation.

Figure 6. Schematic geological logging of Drill hole 3 and its characteristic lithofacies. (A) Obourg Formation white chalk, (B) microconglomeratic chalk, (C) deformation bands with distinct conjugated sets, (D) argillaceous chalk with burrowing and deformation bands, (E) argillaceous chalk with flaser-like clay laminations, (F) glauconitic chalk, (G) conglomeratic chalk, (H) typical bioturbated Saint-Vaast Chalk Formation, (I) argillaceous chalk with flaser-like clay laminations, (J) chert nodules in bioturbated chalk, (K) thin clay-rich layer in a burrowed chalk, (L) highly bioturbated chalk, (M) Glauconitic Maisières Chalk Formation, (N) chert nodule and matrix silicification. Abbreviation: Fm, Formation.

4.1.1. Maisières Chalk Formation

17The Maisières Chalk Formation is a glauconitic calcarenitic chalk that marks the bottom of each drill hole. The thickness of the sediment ranges from 6 to 9 m, i.e. in D1 from 140 to 146 m, in D2 from 81 to 89 m, and in D3 from 130 to 139 m. This rock is characterized by its coarse texture, sand-sized glaucony grains and a high occurrence of bioclasts. The latter, mostly inoceramid bivalves, vary in size from a few millimeters to several centimeters. In D2 and D3, the lower part of the core exhibits numerous altered flint nodules, and the matrix displays local silicification, which is characteristic of the underlying Saint-Denis Silicite and Hautrage Flints formations.

4.1.2. Saint-Vaast Chalk Formation

18In all three drill holes, the Saint-Vaast Chalk Formation is characterized by intense burrowing, evidence of mottling, and recognizable Thalassinoides and Zoophycos trace fossils. The thickness of the formation varies: i.e. in D1 from 76 to 140 m, in D2 from 33 to 81 m, and in D3 from 82 to 130 m. Flint nodules are present within specific intervals in all drill holes and range in size from a few centimeters to 10–15 cm. They are present from 89 to 96 m and from 125 to 140 m in D1, from 64 to 83 m in D2, and from 89 to 95 m and from 109 to 133 m in D3. Localized silicifications of the matrix are observed around the chert nodules, where, unlike within the chert, the chalk matrix texture is preserved. In the lower part of the formation, coarser chalk with glaucony grains is present, either filling burrows or occurring in thin layers within the matrix.

19In D1, the upper part (76 to 102 m) has a higher non-carbonate content with clear cyclic variations. The base of each cycle consists of darker chalk, and the top consists of highly bioturbated material that is slightly lighter in color. In D1, where the cycles are best defined, 92 cycles have been identified. In D2, the core is poorly preserved, and the cycles are not easily identifiable. D3 notably displays an alternation of clean burrowed chalk and very thin clay laminations. In all drill holes, the cycles are thicker in the lower part of the Saint-Vaast Chalk Formation. The average cycle thickness is 50 cm, while the entire formation is composed of gray chalk, extensively bioturbated by Thalassinoides, with no visible siliciclastic components. Observed trace fossils include Chondrites and Zoophycos. The burrowed hiatal surfaces are not clearly defined and correspond to softgrounds. These deposits correspond to the sedimentary cycle types described by Lasseur et al. (2009) in Turonian–Coniacian deposits in Normandy.

4.1.3. Trivières Chalk Formation

20The Trivières Chalk Formation consists of a gray (light to dark) and marly chalk. In D1, the 35 m thick sequence consists of a stacking of 30 to 50 cm thick sedimentary cycles. The cycles are characterized by a marly base, which is poorly consolidated and moderately bioturbated. The top of the cycles is hardened, usually highly bioturbated by Thalassinoides and Chondrites. These are typical firmgrounds as defined by Lasseur et al. (2009) and characterized by the absence of erosion features or shell accumulations.

21Within D2, the Trivières Chalk Formation is also argillaceous, but no sedimentary cycles have been identified. Throughout the 25 m thick sequence (5–30 m), the sedimentary features are obliterated by the presence of linear structures which are darker than the host rock (Fig. 5A). These are thin features (<0.5 mm) developed as anastomosing fracture swarms in the chalk matrix that can extend from a few centimeters to 40 cm in height. These features are also identified in D3, from 23 m to 32 m and from 62 m to 66 m. Some of these swarms are surrounded by a darker area of chalk, which may be attributed to carbonate reprecipitation which seems to initiate or terminate within specific layers, such as clay laminations (Fig. 5B). They were first referred to in literature as (healed) hairline fractures (Jørgensen, 1992; Surlyk et al., 2003). These features have a high angle to bedding and they form a conjugate pattern, as described in literature (Wennberg et al., 2013; Abdallah et al., 2021) (Fig. 6C). Gaviglio et al. (2009) identified these features in white chalk, while Wennberg et al. (2013) defined them as deformation bands, analogous to those encountered in porous sandstone (Aydin & Johnson, 1978).

22Within D3, the Trivières Chalk Formation consists of a 53 m thick argillaceous chalk, ranging from 17 to 70 m. The upper part, from 17 to 23 m, displays sedimentary cycles like the ones described in D1 (Fig. 4C). Intense burrowing is observed throughout the Formation. Clay layers and clay-rich laminated chalk intervals are also present within the succession. Notably only in D3, four distinct layers of micro-conglomeratic to conglomeratic chalk are observed, respectively at depths of 22.90 m, 32.70 m, 35.50 m, and 43.50 m. These polymict conglomerates are composed of glaucony grains, bioclasts, and lithoclasts (including some cherts and chalk intraclasts) that occur within a muddy chalk matrix.

23As mentioned before, the lower part of the Trivières Chalk Formation is characterized by the presence of coarse sand-sized glauconitic chalk, recorded in the three drill holes, i.e. in D1 from 68 to 78 m, in D2 from 30 to 33 m, and in D3 from 70 to 82 m. Clay laminations, clay flasers, and burrows usually filled with coarser material are also typically present within this interval. Some layers, typically a few decimeters in thickness, are identified as hardgrounds. They are lithified, with intense burrowing and the presence of nodules. At the base of the Trivières Chalk Formation, each borehole reveals the presence of conglomeratic chalk layers, i.e. a 30 cm thick conglomerate in D1, a 10 cm thick conglomerate in D2, and in D3, two conglomeratic chalk layers are identified at depths of 77.8 m and 80.5 m, both approximately 20 cm in thickness. Some conglomerates display an erosive base. They are polymictic and their grain size ranges from granules (2–4 mm) to pebbles (4–64 mm), which are commonly rounded and poorly sorted. The conglomerate layers include coarse bioclasts (inoceramid and belemnite fragments), fragments of fishbones, chert clasts, glaucony pellets, quartz grains, and intraclasts of subrounded to well-rounded micritic chalk pebbles. These pebbles display a high concentration of framboidal pyrite along their outer rims.

4.1.4. Obourg Chalk Formation

24The upper part of each core corresponds to the base of the Obourg Chalk Formation. It consists of fine-grained white to yellowish chalk, depending on the degree of weathering. It displays many traces of oxidation, either on fault planes, in bioclasts, or in the matrix itself. The thickness of the Obourg Chalk Formation is 31 m (ranging from 2 to 33 m) in D1, 4.5 m (ranging from 0.5 to 5 m) in D2, and 16 m (ranging from 1 to 17 m) in D3. Previously, phosphatic reworked layers were identified at the base of the Obourg Chalk Formation within the Mons Basin (Robaszynski et al., 2001). Two 10 cm thick phosphatic breccias were identified in D1 and D3 but were missing in D2. The monomict brecciated intervals possess a matrix-supported texture. Here, angular and unsorted clasts of white chalk are dispersed in the phosphatic chalk matrix.

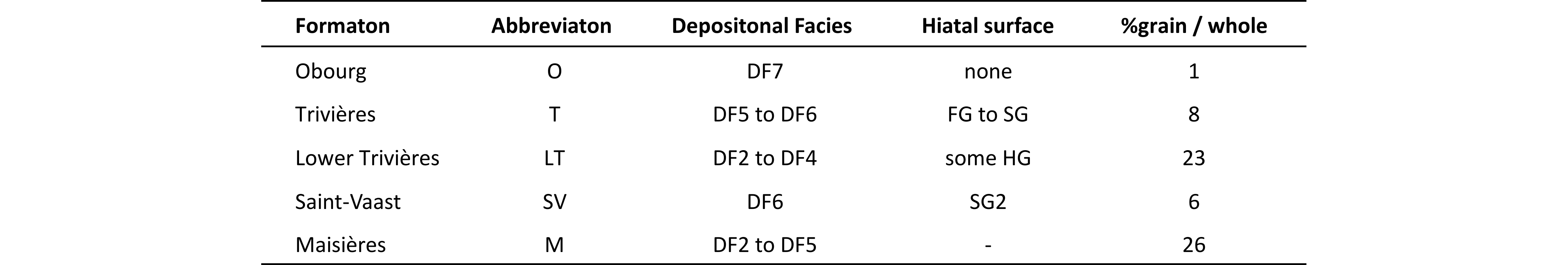

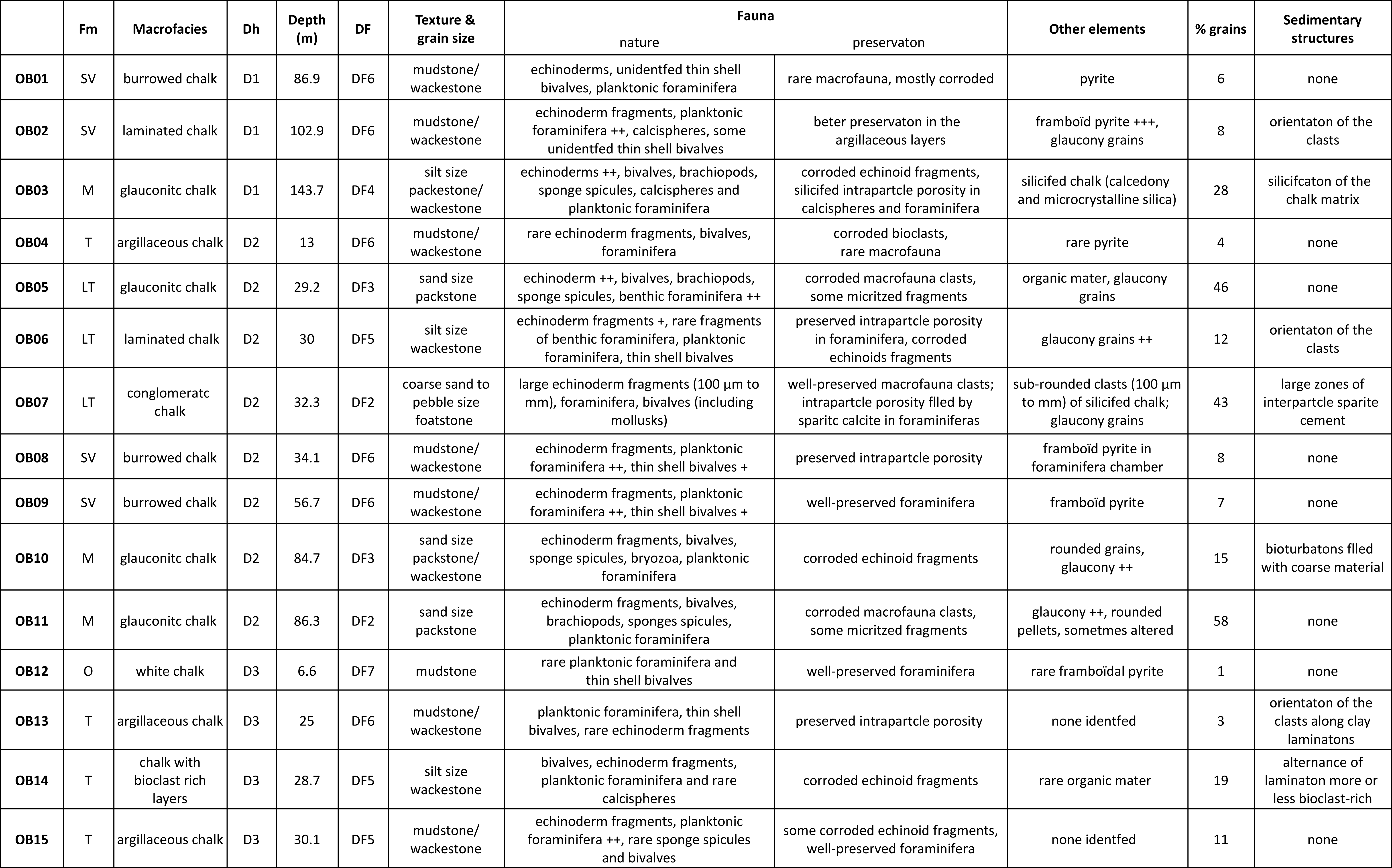

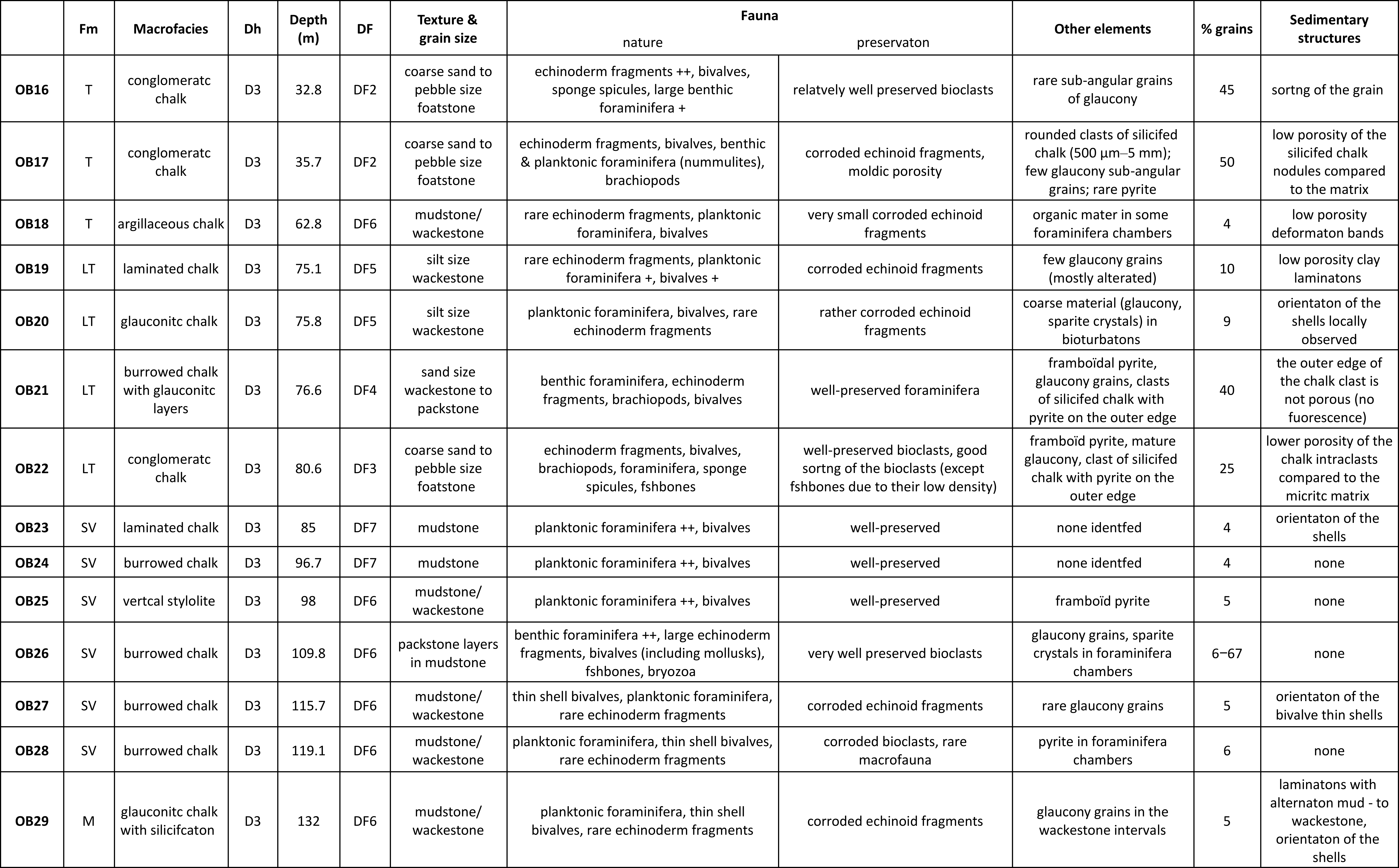

4.2. Petrography

25The depositional facies (DF) and average grain content of the five chalk formations, as defined in Section 3.3, were identified through petrographic observations which are summarized in Table 1. Only DF2 to DF7 are identified in this study. The grain content generally decreases from DF1 (medium sand packstone to grainstone) to DF7 (mudstone), as schematized in Figure 3. The abundance of broken shells, the coarser grain size, and better sorting that decrease from DF2–3 to DF5, reflect a more hydrodynamic setting. Facies DF2–3 to DF5 were interpreted as upper offshore deposits by Lasseur et al. (2009). DF6 and DF7 do not display evidence of sorting, as reflected by their mudstone texture. Macrofossils are rare to absent, and the facies are dominated by planktonic microfossils, revealing a deeper depositional setting. DF7 consists of pure mudstones composed of coccolith fragments deposited by settling. DF6 and DF7 are thus associated with deeper offshore environments. Detailed observations made on each thin section are documented in Table 2.

Table 1. Summary of the depositional facies (DF), hiatal surfaces and percentage of grains from point counting on thin section, for each stratigraphic formation. Hiatal surfaces include FG: firmground, SG: softground and HG: hardground.

Table 2. Petrographic description of the thin sections. Abbreviations: Dh, drill hole; DF, depositional facies; Fm, formation; LT, Lower Trivières; O, Obourg; M, Maisières; SV, Saint-Vaast; T, Trivières. Depositional facies according to Lasseur et al. (2009) and texture according to Dunham (1962). Percentage of grains calculated using JMicroVision (Roduit, 2008).

26For each sample, the grain percentage of the total sample was determined. Grains, defined as constituents larger than 20 µm, encompass macrofauna (fragments of bioclasts from bivalves, echinoderms, bryozoans, inoceramids, etc.), microfauna (calcispheres, planktonic and benthic foraminifera), and other components (glaucony pellets, quartz grains, etc.).

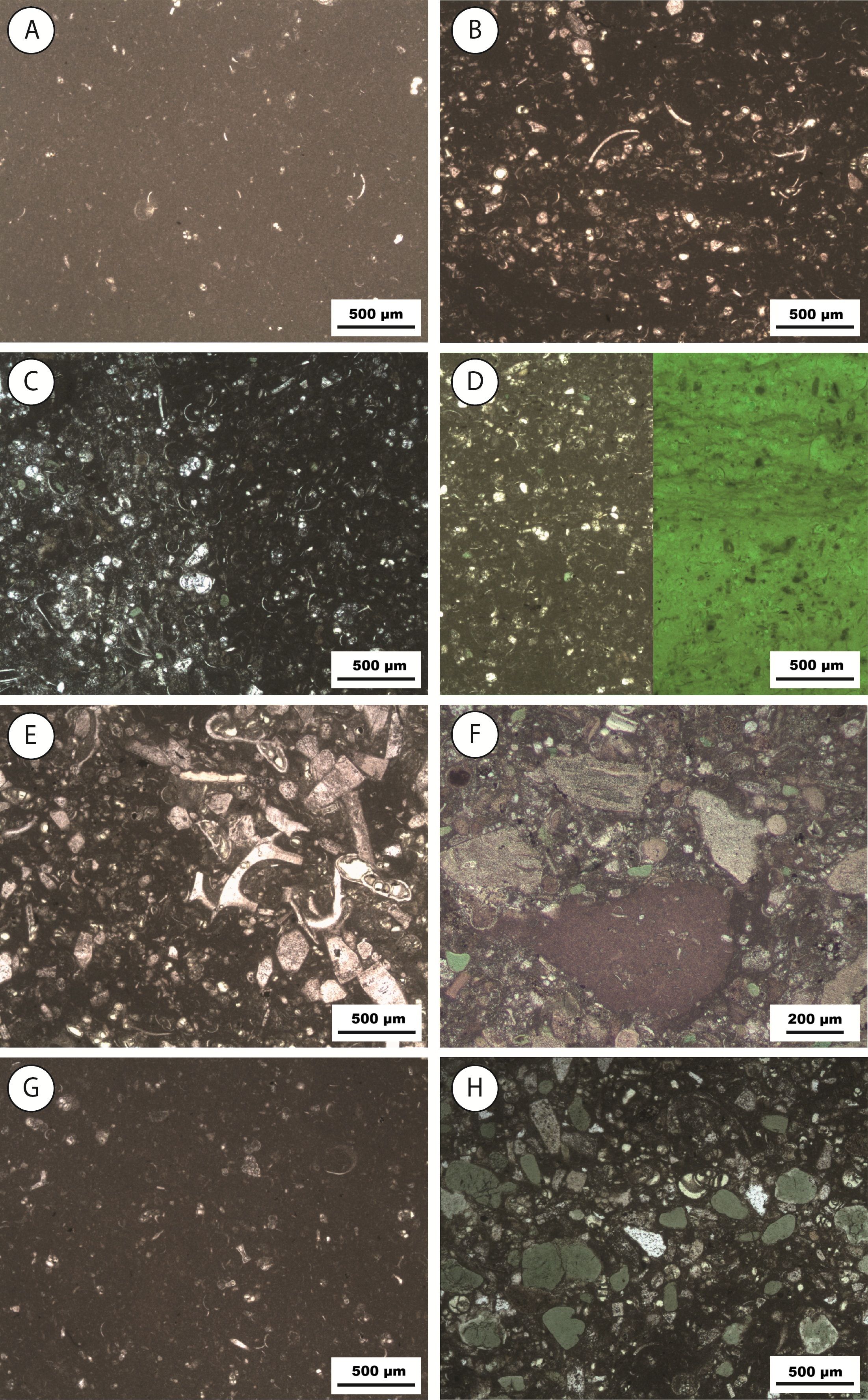

27The following main observations were made based on thin section observations (Figs 7 and 8):

-

The samples from the Saint-Vaast Chalk Formation average 6% grains, ranging from mudstone to mudstone–wackestone containing calcispheres and planktonic foraminifera. Rare, rounded grains of glaucony are observed in the upper part of the Formation (Fig. 7G).

-

The upper part of the Trivières Chalk Formation is also categorized as mudstone–wackestone, with an average grain content of 8%. Within this and the former formation, grains are mainly biogenic. Bioclasts (echinoderms, bryozoa, etc.) dominate the coarse fraction. Rare, rounded grains of glaucony are observed in this part of the Formation (Fig. 7B).

-

The lower part of the Trivières Chalk Formation, in contrast, contains 23% grains, including glaucony pellets, mainly ranging from 20 to 100 µm, which yield different states of alteration. Glaucony grains are sub-rounded to well-rounded, and some present cracks. Authigenic quartz crystals and framboidal pyrite are also observed in the interval. Fluorescence observations allow to recognize clay laminations, which are not visible otherwise. The presence of clays makes the matrix less porous, and it appears darker when viewed under fluorescent light. The micritic matrix also underwent local silicification by calcedony. The cryptocrystalline silica progressively transforms the chalk matrix, resulting in the creation of a silicification front that appears completely non-porous under fluorescent light. Some framboidal pyrite is observed in the matrix or foraminifera chambers, as well as sparitic cement (Figs 7C–D, 8A, 8E).

-

Within the Maisières Chalk Formation, the coarse fraction accounts for approximately 26% and consists essentially of large glaucony pellets ranging in size from 50 µm to 1 mm. The grain maturity ranges from evolved to well-evolved. The alteration and cracks of the grains are variable, but their morphology is consistently sub- to well-rounded. Interestingly, a number of these grains display an external alteration rim that is manifested by a color ranging from light green to white. In contrast, the internal glaucony grain coloration is vivid green. The discoloration suggests a potential variation in the mineralogical composition or state of weathering within the same grain. Grains also include large bioclasts, which are frequently corroded. Local matrix silicification by calcedony also occurs (Figs 7H, 8F).

-

The sample from the Obourg Chalk Formation contains 1% grains, which is consistent with a mudstone facies. The rare grains include planktonic foraminifera and the shell of thin bivalves (Fig. 7A).

-

As expected, the four conglomeratic chalk samples from Trivières Chalk Formation have a higher grain-to-sample ratio, averaging 41%. Upon microscopic examination, it is observed that the conglomerates incorporate unsorted grains varying in size from several tens of micrometers to millimeters. The constituents include grains of glaucony, which are rounded, altered, and occasionally broken. There are also intraclasts of chalk, which are sometimes silicified. Large bioclasts (including fishbones), benthic foraminifera and reworked quartz grains are also present (Figs 7E–F, 8B–D).

Figure 7. Depositional facies. (A) Sample OB12, Obourg Chalk Formation, mudstone, DF7; (B) Sample OB14, Trivières Chalk Formatrion, silt-size wackestone, DF5; (C) Sample OB20, lower part of the Trivières Chalk Formation, silt-size wackestone–packestone, DF5; (D) Sample OB19, lower part of the Trivières Chalk Formation, laminated silt-size wackestone, DF5; (E) Sample OB16, Trivières Chalk Formation, conglomeratic coarse sand to pebble size floatstone, DF2; (F) Sample OB22, lower part of the Trivières Chalk Formation, conglomeratic coarse sand to pebble size floatstone, DF3; (G) Sample OB24, Saint-Vaast Chalk Formation, mudstone, DF7; (H) Sample OB11, Maisières Chalk Formation, sand-size packstone, DF2.

Figure 8. (A) Sample OB02, framboidal pyrite in a foraminifera chamber, lower part of the Trivières Chalk Formation – incident light; (B) Sample OB07, conglomeratic chalk with a large chalk intraclast (left) cemented by sparitic calcite crystals, lower part of the Trivières Chalk Formation – natural light; (C) Sample OB07, conglomeratic chalk with sparitic calcite cementation, lower part of the Trivières Formation – polarized light; (D) Sample OB16, Conglomeratic chalk with large bioclasts and foraminifera, Trivières Chalk Formation – natural light; (E) Sample OB21, silicification front, showing no porosity under fluorescence; lower part of the Trivières Chalk Formation; (F) Sample OB11, grain of glaucony showing zonation, Maisières Chalk Formation – natural light.

4.3. Microtextures

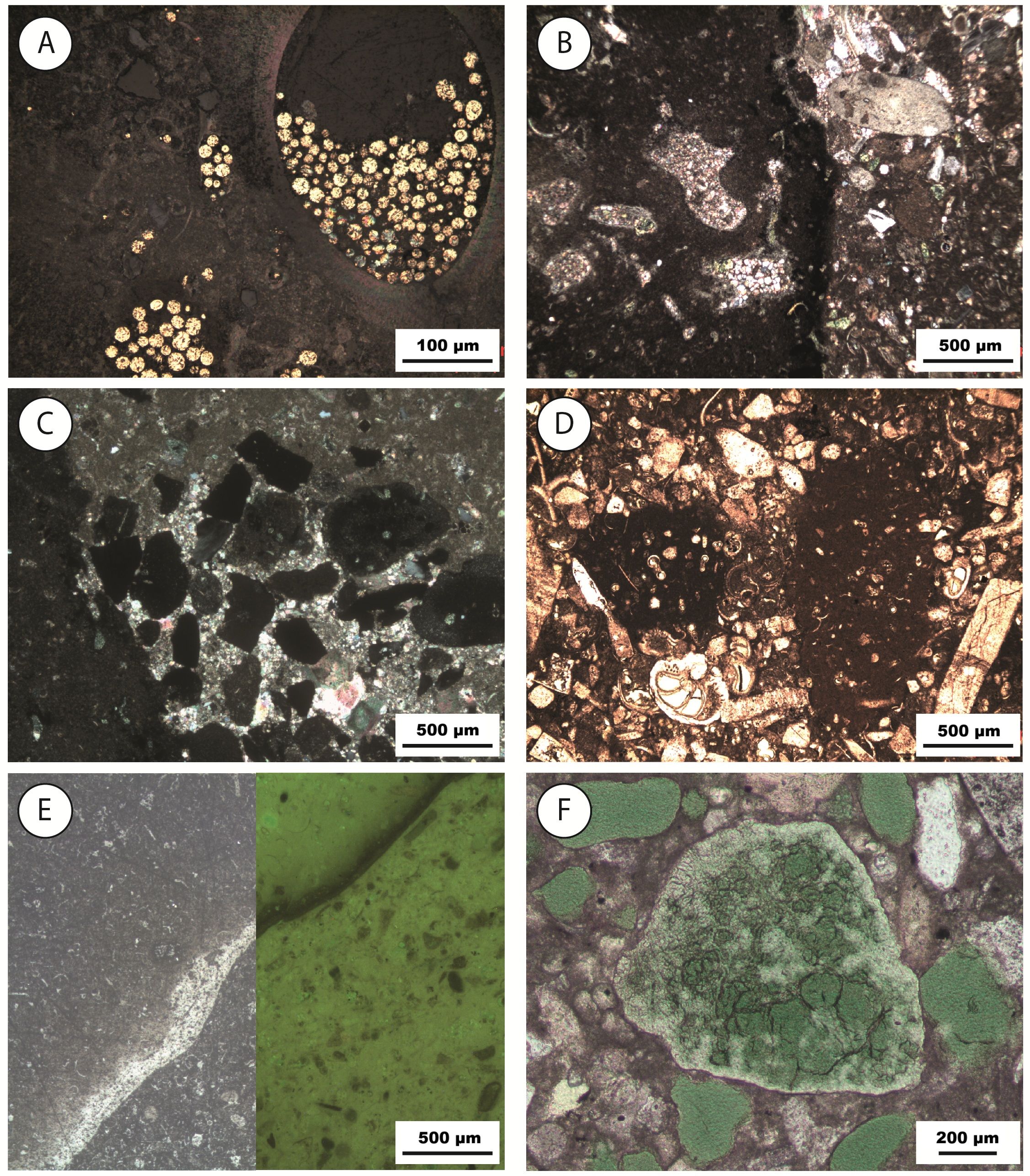

28Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) observations enabled the characterization of the microtexture variations in chalk across the different formations (Fig. 9). The description of these microtextures is based on visual criteria and the terminology established by Saïag et al. (2019). For all samples, the primary component of the matrix consists of fragmented coccoliths.

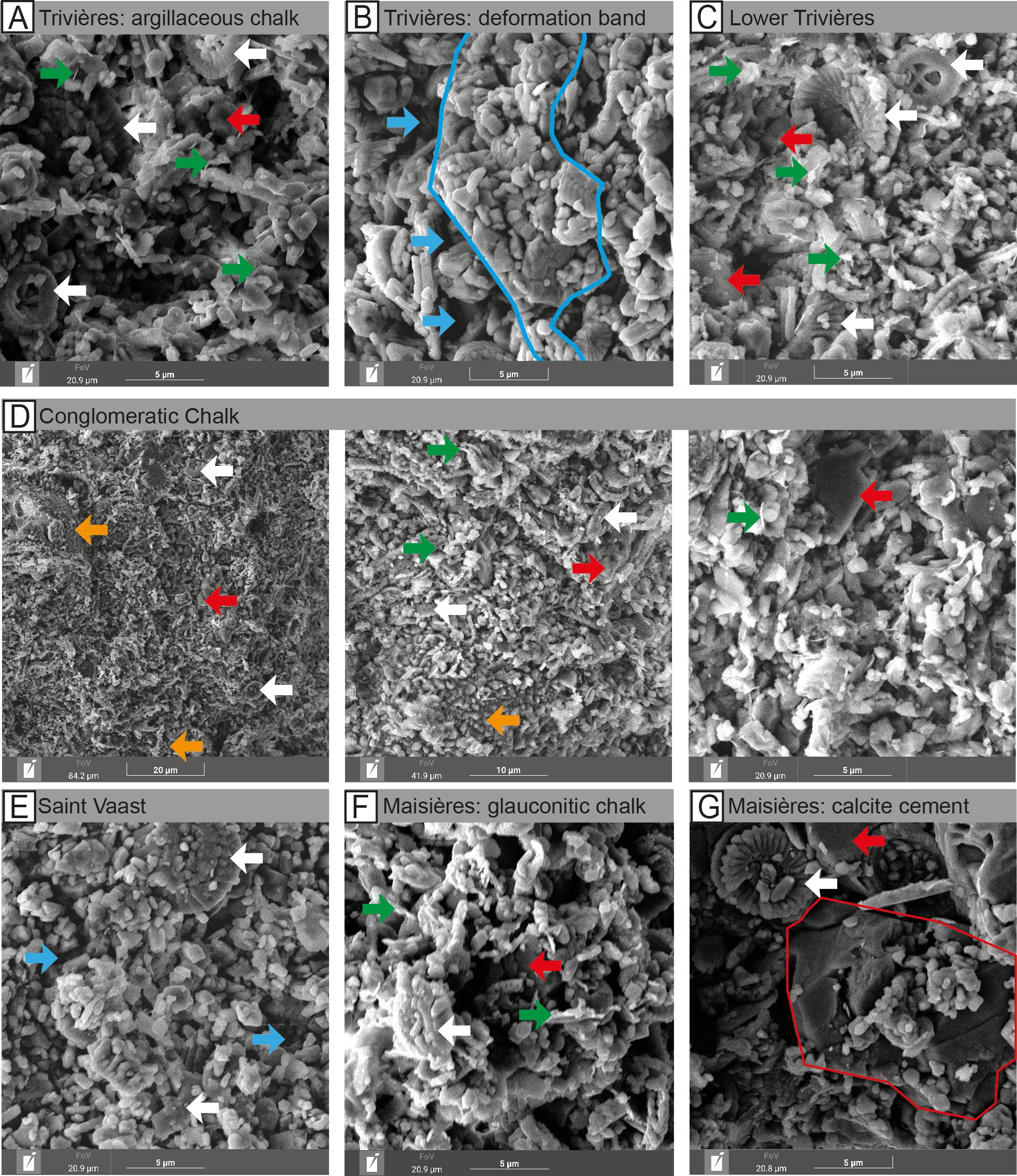

29The Trivières Chalk Formation samples have a dispersed clay microtexture. Phyllosilicates occur scattered within the matrix as thin clay sheets approximately 1 µm long. A biogenic fraction is omnipresent and well preserved. The micrite exhibits a microrhombic texture, with both subhedral and euhedral micrite grains, displaying punctate to serrate contacts. Cements are scarce and manifested as euhedral authigenic calcite crystals within intraparticle porosity (Fig. 9A).

30The deformation bands observed in D2 and D3 can be seen under the SEM, accompanied by localized changes in the matrix microtexture. These bands, ranging in width from a few tens to several hundreds of micrometers, exhibit local pore collapse and a reduction in pore spaces. There is also a reorganization of the grains, and the contacts between grains appear serrated to coalescent within these bands. There is little evidence of pressure dissolution at the grain contacts (Fig. 9B).

31A serrate subhedral microtexture characterizes the Saint-Vaast Chalk Formation. It contains an abundant biogenic fraction and the coccoliths are well preserved. The micrite, which ranges from sub- to anhedral, exhibits punctic to serrate grain contacts. The presence of cement in this formation is rare (Fig. 9E).

32The microtextural characteristics of the chalk in the lower part of the Trivières Chalk and the Maisières Chalk formations exhibit significant similarities. These are characterized by a high proportion of phyllosilicates, clay sheets and fibers dispersed in the matrix, which are likely the result of the decomposition of fragile glaucony grains. Coccoliths are well preserved. The micrite is anhedral, with contact types ranging from punctic to serrate. Cementation is frequently observed, often in the form of large calcite or sparite crystals filling the interparticle porosity, which size spans from a few micrometers to over 50 µm (Fig. 9C, 9F).

33The conglomeratic chalk intervals also have a dispersed clay microtexture. Some sparitic cement patches are observed, but the interparticle porosity is retained and the coccoliths are well preserved. SEM observations also allow the identification of a rim of hydroxyapatite crystals coating some grains in the lower part of the Trivières Chalk Formation and conglomeratic chalk (Fig. 9D).

Figure 9. Microtextures within D3: (A) Trivières Chalk Formation (22 m); (B) Deformation band in the Trivières Chalk Formation (69 m); (C) Lower part of the Trivières Chalk Formation (83 m); (D) Conglomerate in the Trivières Chalk Formation (80 m); (E) Saint-Vaast Chalk Formation (94 m); (F–G) Maisières Chalk Formation. Arrows indicate (red) cements, (green) clay sheets, (white) intact coccoliths, (blue) interparticle porosity, (orange) hydroxyapatite grain coating. Highlighted in blue: zone of low interparticle porosity related to local pore collapse within deformation bands. Highlighted in red: large zone of calcite cementation in the matrix of the Maisières Chalk Formation (137 m).

4.4. Mineralogy

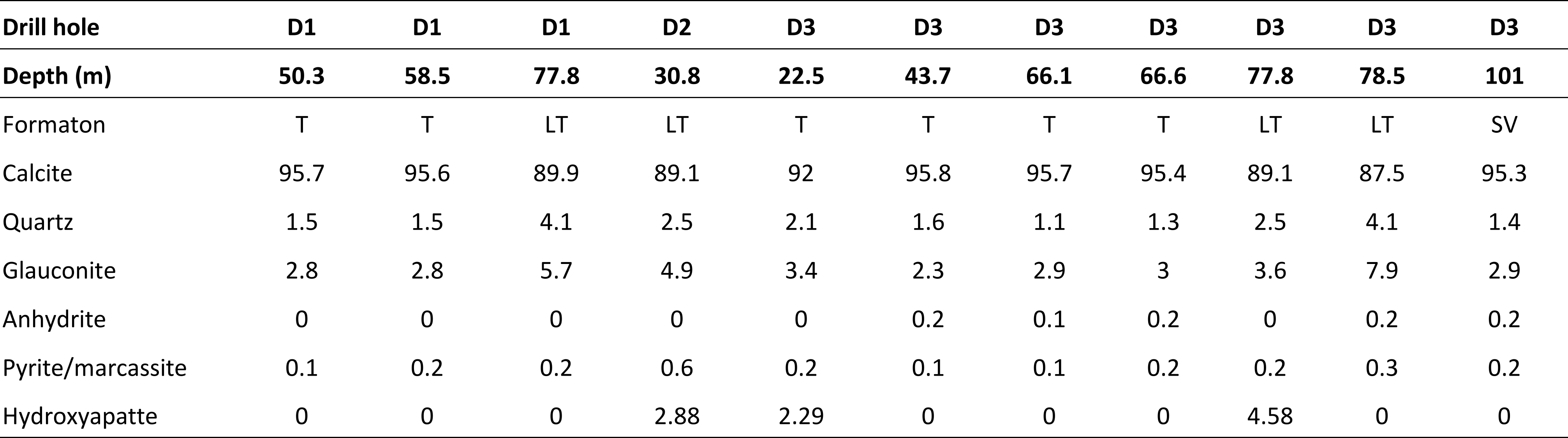

34Mineralogical XRD analyses were conducted on a total of 11 samples, from three different formations: 6 from the upper and middle Trivières Chalk Formation (which included one layer of conglomeratic chalk), 4 from the lower part of the Trivières Chalk Formation, and 1 from the Saint-Vaast Chalk Formation. The results (Table 3) reveal that the lower Trivières Chalk Formation has the highest non-carbonate fraction with 11.1%, compared to about 5% in the rest of the Trivières Chalk and Saint-Vaast Chalk formations. Despite its very clayey appearance, even marly in places, the Trivières Chalk Formation has a relatively low non-carbonate content. All samples contain quartz, phyllosilicate (specifically glauconite), and pyrite. The lower part of the Trivières Chalk Formation is notable for its glauconite content, which reaches up to 7.9%, and its quartz content, which varies between 2% and 5%. This is significantly higher than the less than 2% found in the other formations. Hydroxyapatite is also detected in three samples from the lower part of the Trivières Chalk Formation and one conglomeratic layer in D3, ranging from 2% to 5%.

Table 3. Results of the XRD measurements in %. Abbreviations: LT, Lower Trivières; SV, Saint-Vaast; T, Trivières.

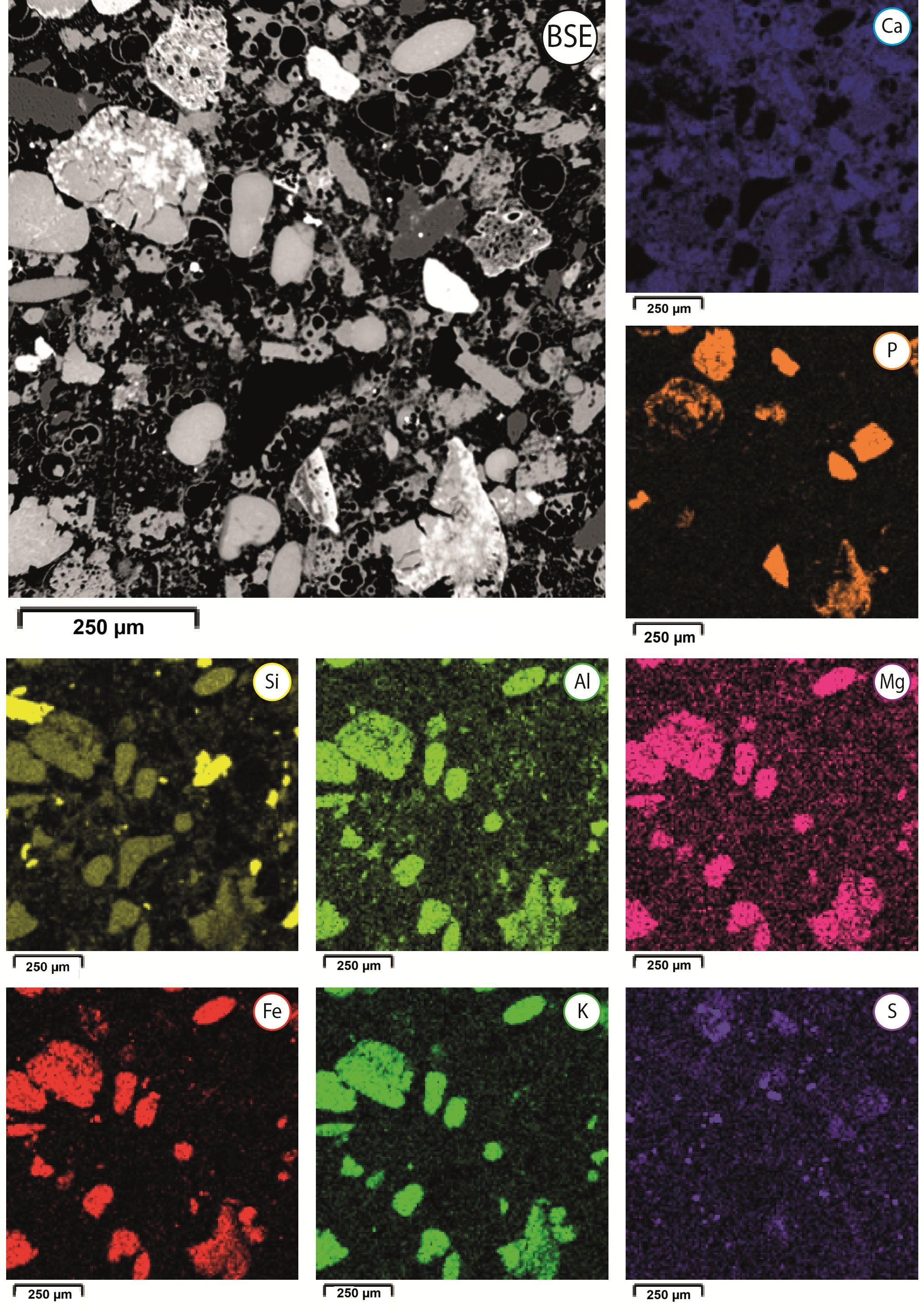

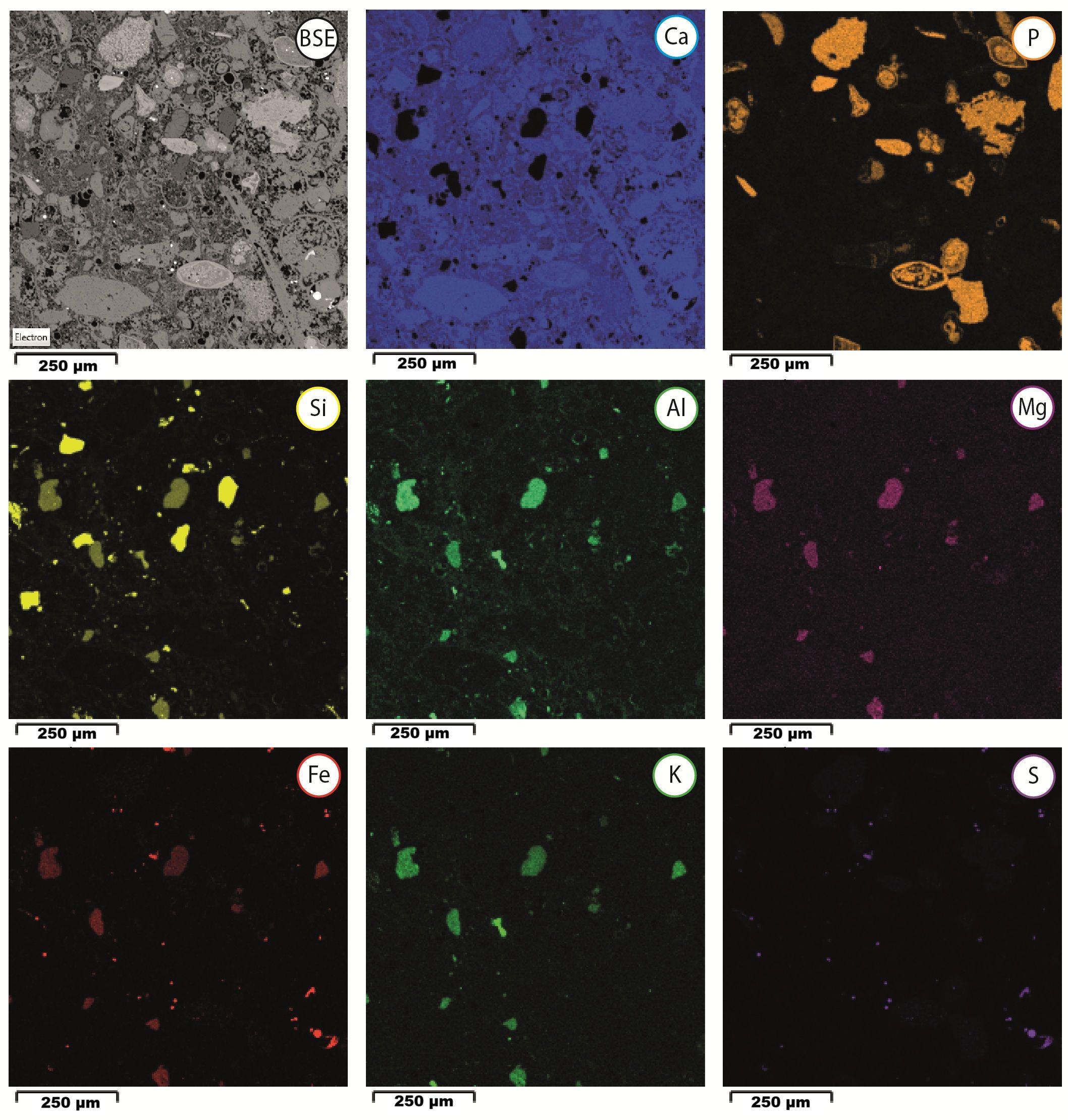

35Element mapping was conducted using Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDX) on two distinct samples: a glauconitic chalk from the Maisières Chalk Formation (Fig. 10) and a conglomeratic chalk layer from the lower part of the Trivières Chalk Formation (Fig. 11). In both samples, the micritic matrix is identified as calcite. Quartz grains are also identified within the matrix. Elements containing both calcium and phosphorus are observed. Their honeycomb structures and chemical composition suggest they correspond to fishbone fragments.

36Backscattered electron images of the glauconitic chalk enabled the identification of glaucony grains, recognizable by their shape and characteristic cracks. Element mapping confirmed the composition of these grains, which contain potassium (K), iron (Fe), aluminium (Al), magnesium (Mg), and silicon (Si). These elements constitute the chemical formula of glauconite, which is (K,Na)(Fe,Al,Mg)2(Si,Al)4O10(OH)2. Phosphorus is also detected in certain glaucony grains, suggesting its integration into their composition. Notably, some glauconite grains exhibit some zonation, with phosphorus only partially integrated into the composition of the elements, indicating a partial phosphatization process. Phosphorus is densely concentrated within the cracks of glaucony. The progression of phosphatization appears to occur through these cracks within the grains. In the conglomeratic chalk, element mapping highlights the calcite nature of the micritic matrix, which is primarily made up of coccolith fragments. Large bioclasts of 200–300 µm (Ca), quartz (Si) and framboidal pyrites (Fe, S) are also highlighted. Many grains are also rich in phosphorus, including what appears to be fishbones, but not only. Marine organisms whose tests are normally made of low-Mg calcite, likely ostracods, regularly show a high concentration of phosphorus. The tests of these organisms thus have undergone phosphatization. Similarly, as with the glauconitic chalk, glauconite grains are identifiable, and some show a high concentration of phosphorus, partially or within the entire grain.

Figure 10. EDX element mapping of a glauconitic chalk sample (OB11) from the Maisières Chalk Formation. Phosphate associated with the glauconitic chalk shows a clear elevation with regard to P content. Glaucony grains contain increased contents of Fe, Al, K and Mg. Quartz grains contain increased contents of Si. Pyrite shows high content of Fe and sulfides (S).

Figure 11. EDX element mapping of a conglomeratic chalk (OB 22) from the lower part of the Trivières Chalk Formation. The micritic matrix and the calcite cementation are observed (Ca). Phosphate shows a clear elevation with regard to P content. Glaucony grains contain increased contents of Fe, Al, K and Mg. Quartz grains contain increased contents of Si. Pyrite shows high content of Fe and sulfides (S).

5. Discussion

5.1. Depositional setting

37The discussion will focus on the depositional setting and the evolution of the depositional environment throughout the succession. For this purpose, the origins of the glauconitic chalk and the conglomerates will first be addressed.

5.1.1. Origin of the glauconitic chalk intervals

38The two glauconitic chalk intervals are located at the lower part of the Trivières Chalk and the Maisières Chalk formations at the beginning of the chalk sequence. These two intervals are marked by the presence of glauconite, pyrite, calcite cementation, silicification and phosphatization. They are referred to as hardgrounds in literature (Robaszynski et al., 2001). Highly cemented and burrowed layers were identified. In both intervals, phosphatization is evident through petrography and EDX chemical analyses. Phosphatization affects both the glaucony grains and biogenic components. According to Muscente et al. (2015), the phosphatization of fossils likely takes place in shallow, subtidal sediments near the boundary between suboxic and anoxic conditions in sediments beneath oxic bottom waters. The association of glauconite and phosphate in hardgrounds has been documented on a sub-microscopic scale from the Cenomanian of Devon, Southwest England (Carson & Crowley, 1993). These authors also located the formation of glauconite and phosphate in a suboxic zone. Most models for marine sedimentary phosphate generation require upwelling/advection of deep nutrient-rich seawater onto a shelf area where water mass mixing generates high organic activity, inducing phosphate precipitation (e.g. Flexer et al., 1989; Jarvis, 2006; Mortimore et al., 2017). According to Banerjee et al. (2019), the association of phosphorite and glauconite in both modern and ancient sediments is observed within a narrow zone that lies between the upper slope and outer shelf, closely associated with the oxygen minimum zone. The warm and humid climatic conditions during the Late Cretaceous likely enhanced the rate of continental weathering. Consequently, an increased supply of K, Fe, Si, Al, and Mg ions into the shallow marine environment via rivers, likely raised the alkalinity of oceans, promoting the formation of glauconite (Bansal et al., 2019).

39The glauconitic chalk intervals of the Maisières Chalk Formation and the lower part of the Trivières Chalk Formation are two reference levels in the chalks of the Mons Basin, which are both situated at the base of major transgressive episodes. The omnipresence in these two levels of (1) glauconite deposition, (2) early calcite cementation, creating hardgrounds, (3) silicification, (4) phosphatization, and (5) framboidal pyrite formation allows a better understanding of the depositional settings. During these low sea-level intervals, precursor to major marine transgressions (see Section 5.3.), ocean water circulation likely changed in the “Chalk Sea”, entering the Mons Basin at that time. In the Late Cretaceous, there were major changes in ocean circulation between the Cenomanian (100.5–93.9 Ma) and Maastrichtian (72.1–66.1 Ma) stages. The paleogeographic transformation and ocean openings likely had a considerable impact on oceanic water circulation (Ladant et al., 2020). While there was continuous deep-water production in the southwestern Pacific, the opening of the Atlantic and Southern Ocean led to a more global oceanic circulation and enhanced meridional exchange. Upwelling currents were therefore present during the majority of the Late Cretaceous, resulting in abundant marine life dominated by coccolithophorids, planktonic foraminifera, radiolarian, ammonites, clupeoid fish, and mosasaurs. The proliferation of siliceous organisms, such as radiolarian, provided the silica necessary for the cryptocrystalline silicifications observed in the samples. While surface waters teem with life due to an abundant import of nutrients, the deep waters carried by upwelling currents are depleted in oxygen. The hypoxic to anoxic nature of the seabed provided the ideal conditions for the formation of glaucony grains. The chemical elements necessary for the formation of glauconite may be provided either by the increase in terrigenous input, as well as the nutrients from the upwellings, or both. The alteration of the glaucony grains, ranging from slightly evolved to evolved, is likely to be associated with remobilization of parautochthonous glaucony grains by the currents. López-Quirós et al. (2019) showed that altered glauconite grains may have been transported from nearby areas and do not necessarily require long transportation to present an evolved texture with alteration rims and cracks. The latter authors suggested that when the glaucony is immature, any transport experienced by the soft, clayey pellets can result in their disaggregation. That phenomenon may explain the origin of the small clay sheets and fibers dispersed in the matrix of Trivières and Maisières Chalk. The bottom sea currents generated by the upwellings also resulted in the winnowing of fine-grained particles, and the formation of hardgrounds, with eogenetic calcite precipitation. The decrease in the sedimentation rate prolongs chemical exchanges at the seawater–sediment interface, a prerequisite for the formation of glauconite (Odin & Matter, 1981) and the phosphatization of deposits. The presence of phosphatization preferentially within the cracks of the glauconite grains suggests that glauconite formed first, which was then altered before phosphatization took place. The euxinic conditions of the bottom waters are also suitable for the precipitation of framboidal pyrite, forming during early authigenesis in reducing microenvironments within dysoxic sediments (Tribovillard et al., 2008).

5.1.2. Origin of the conglomerates

40The lack of organization, the chaotic fabric and the mud-grade matrix of the identified conglomerates are all indicative of mass flow processes according to Pickering et al. (1986). The conglomerate fabric corresponds to the matrix-supported structureless gravelly muds with 50–95% mud-clay grade sediment described by the former authors. They are believed to result from cohesive debris flows, as shear stress at the base of the flow becomes less than the cohesive strength. Such conglomerate beds are typically laterally discontinuous and very irregular in geometry, which is coherent with the fact that some conglomeratic layers are identified in D3 but not in the other nearby drill holes. These conglomerates also typically display variations in the degree of internal organization, matrix content and bed shape over very short lateral distances.

41The conglomerate layers are polymictic, containing large bioclasts, fishbone fragments, well-preserved benthic foraminifera, quartz, feldspar, chert fragments and chalk intraclasts. The intraclasts are sometimes silicified and/or lithified by calcite cement. Based on the conglomerate composition, it appears that the material is being sourced from within the same depositional basin. The conglomeratic layers are under- and overlain by undisturbed cyclic chalk/marl couplets in the Trivières Chalk Formation, which were deposited in a deep-water environment, likely below storm wave base, in a lower offshore setting. In contrast, the numerous benthic foraminifera that constitute the conglomerate, however, attest to a more proximal origin. The intrabasinal origin of the conglomerate implies that the material comes from a slightly more proximal position along the carbonate platform. This is confirmed by the presence of benthic foraminifera, which are typically associated with upper offshore deposits on the Chalk Sea platform (Lasseur et al., 2009). The rapid tectonic subsidence of the Mons Basin during the early Campanian, which coincided with the deposition of Trivières Chalk Formation, could have triggered sediment instability and initiated local movements of gravity flow from the proximal part of the basin towards deeper water. Therefore, the diachronous and thin conglomerates rather reflect local destabilization and minor gravity flow, rather than large-scale sediment mass flow movements.

5.1.3. Reconstitution of the depositional environment

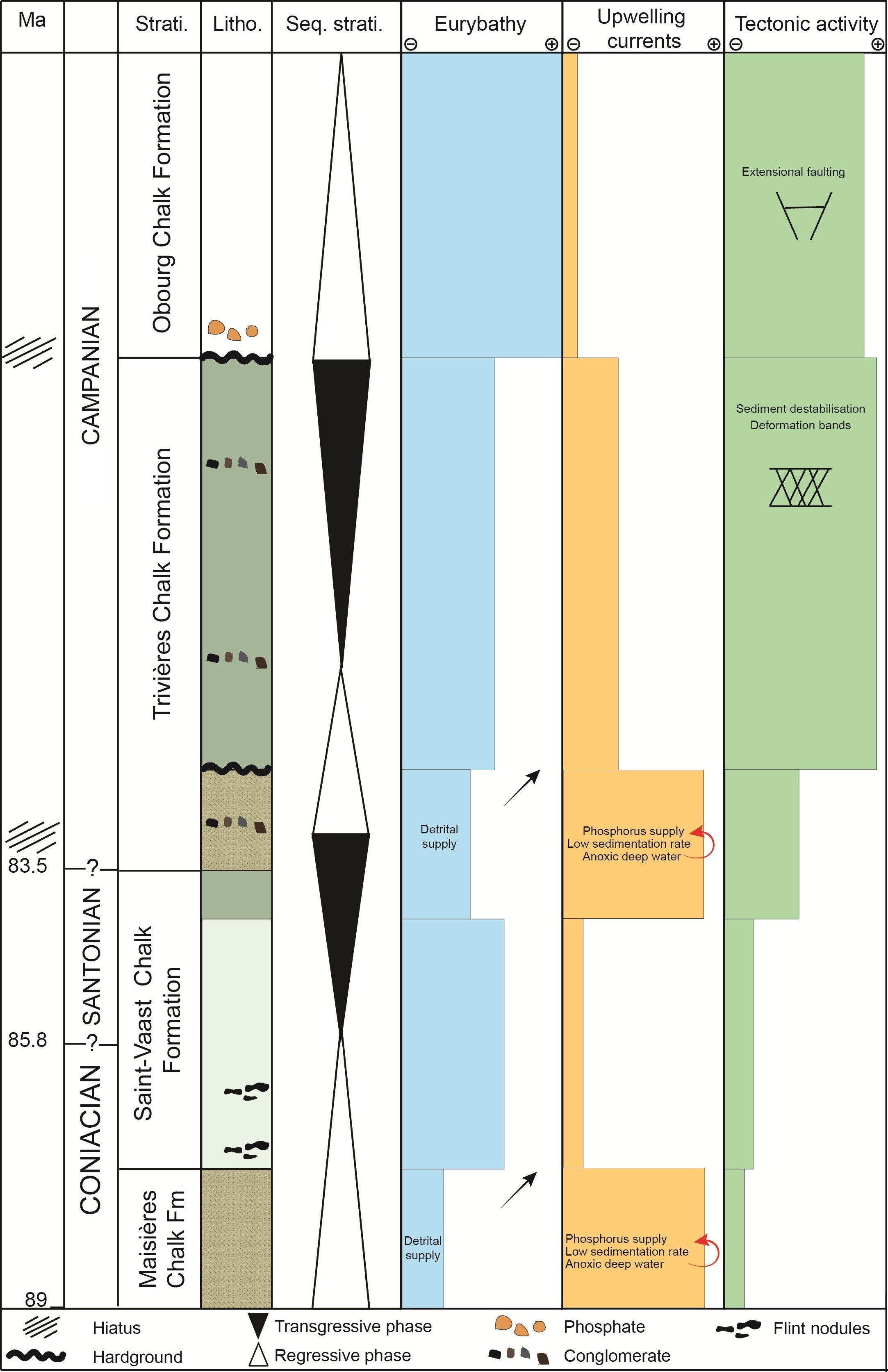

42Changes in the depositional environment throughout the studied Coniacian–Santonian chalk succession appear to be influenced by three main parameters in the Mons Basin (Fig. 12): (1) Eurybatic variations, which refer to local or relative sea-level changes (Haq, 2014), as opposed to eustatic changes that imply global sea-level variations; (2) Variations in marine currents and the resulting stratification of water masses; (3) Active tectonism causing the basin to subside.

43The confined paleogeography and rapid subsidence of the Mons Basin at the time facilitated a swift overall facies transition from a very proximal (Maisières Chalk Formation) to a distal environment (Obourg Chalk Formation) in chalk deposition. Facies changes in the Mons Basin at the Coniacian–Santonian limit align well with the large-scale observations of the chalk succession in northwestern Europe. The Chalk succession thins eastward towards the margins of the Anglo-Paris Basin (Gale, 2024). The Mons Basin chalk succession offers a unique, condensed sequence of chalk facies observed throughout the entire Anglo-Paris Basin (Robaszynski et al., 2001).

Figure 12. Simplified log of the stratigraphic succession from Maisières Chalk Formation to Obourg Chalk Formation in the Mons Basin. Highly schematic summary of the main processes (eurybathy, upwellings, and tectonics) that affect chalk deposition from the Coniacian to the Lower Campanian. The very relative importance of each process is represented by each stratigraphic formation. Abbreviations: Fm, Formation; Litho., lithology; Seq. strati., sequence stratigraphy; Strati., stratigraphy.

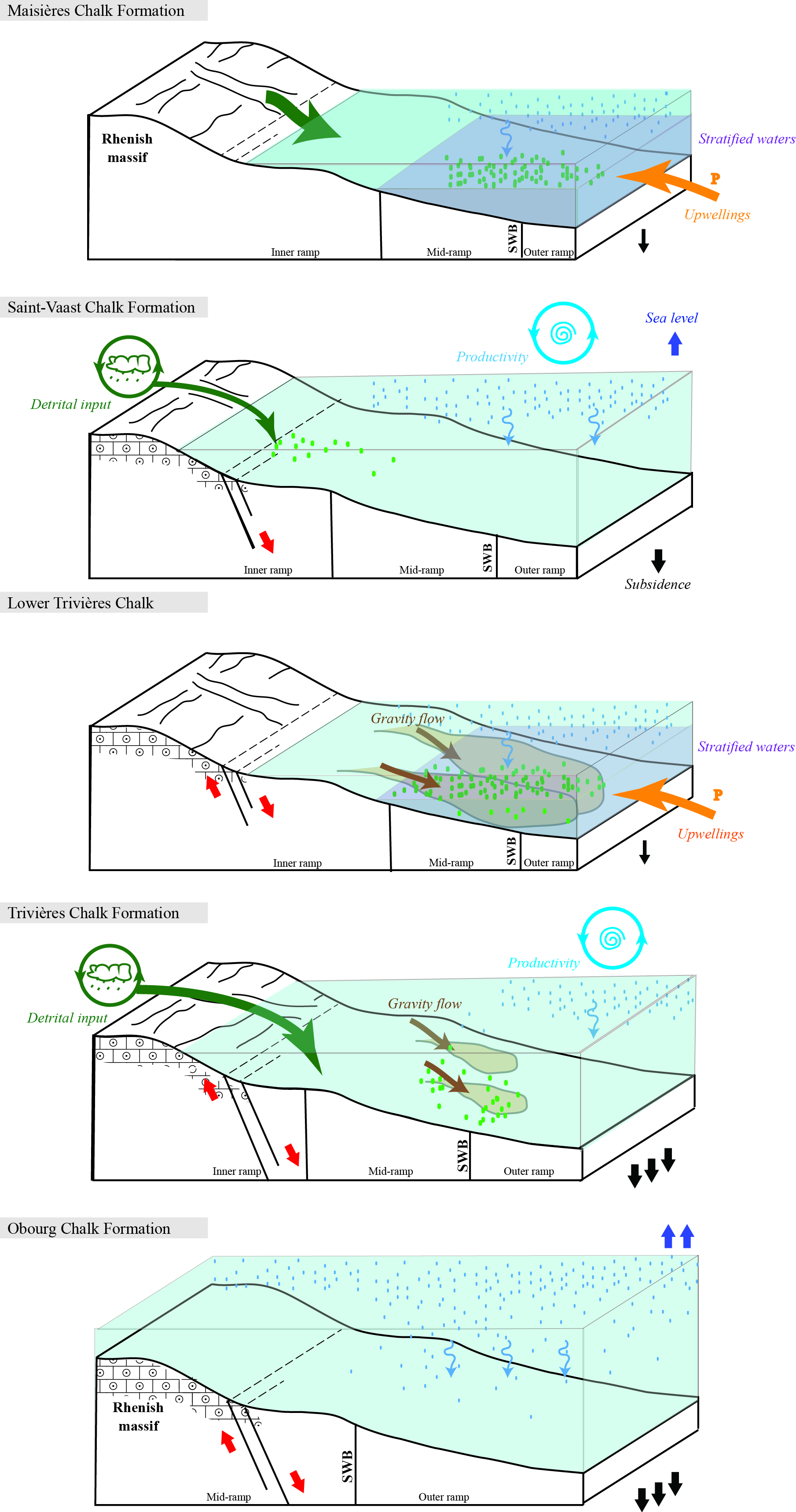

44A schematic paleoenvironmental reconstruction is proposed for each of the formations in Figure 13.

-

Maisières Chalk Formation

45At the base of the studied deposits, the Maisières Chalk Formation represents the beginning of a major transgressive sequence starting with a condensed interval, as discussed in Section 5.1.1. Glauconite deposits often correlate with lowstand systems and/or the early stages of transgressive sequences in geological records (e.g. Banerjee et al., 2019; Bansal et al., 2019). The Maisières Chalk Formation deposits likely formed in a relatively shallow environment, probably in a lower offshore mid-ramp environment according to Lasseur et al. (2009). Stratified water and oxygen depletion in deeper waters are also typical characteristics of the onset of transgressive trends. The Maisières Chalk Formation was deposited during the early Coniacian. Facies of glauconitic chalk, referred to as the Lezennes Chalk, have been identified in northern France at the same stratigraphic level by Amédro et al. (2023). This lithostratigraphic interval is recognized as a condensed interval throughout the entire Anglo-Paris Basin (Gale, 2024; Amédro et al., 2025).

-

Saint-Vaast Chalk Formation

46The rise in sea level led to an increase in accommodation space, which probably altered the patterns of water circulation and reduced the impact of upwellings on the deposits under study. This major transgression likely transformed the paleogeography of the coastline and the shape of the Mons Basin. While the basin may have remained isolated during the deposition of the Maisières Chalk Formation, it eventually became widely connected to the chalk sea towards the Paris Basin during deposition of the Saint-Vaast Chalk Formation from 87 to 84.65 Ma (Robaszynski et al., 2001). The Formation is composed of stacked sedimentary layers. DF6 or DF7 associated with poorly expressed hiatal surfaces correspond to upper offshore deposits that accumulated below storm wave base according to Lasseur et al. (2009). The origin of these sedimentary cycles can be traced back to the paleoclimatic Milankovitch cyclicity, a phenomenon previously described in chalk (e.g. Lauridsen & Surlyk, 2008; Lasseur et al., 2009; Naujokaitytė et al., 2021). In D1, 92 sedimentary cycles have been counted over this period of 2.35 million years. A rough estimate then suggests that the average cycle duration is approximately 25,500 years, aligning with the equinox precession cycle of 26,000 years. Milankovitch cycles appear to influence the ratio between terrigenous input and biogenic fraction, which has an impact on both the weathering of the land and plankton productivity (Gräfe, 1999). In the upper part of the Saint-Vaast Chalk Formation, the non-carbonate content is higher and the sedimentary cycles are thinner and more distinct. The global eustatic level, as defined by Haq (2014), seems to align with local sea-level variations in the Mons Basin. The changes in facies appear to be primarily controlled by sea-level variations in the lower part of the sequence (Fig. 12).

-

Lower part of the Trivières Formation

47The lower part of the Trivières Chalk Formation, extensively discussed in Section 5.1.1., bears a resemblance to the Maisières Chalk Formation and is associated with a stratigraphic hiatus at the limit Santonian–Campanian (Fig. 1). However, they differ in that the biogenic fraction is more prevalent and there are fewer glauconite grains in the former deposits. The impact of upwelling currents is significant, leading to phosphatization, silicification, and the winnowing of fine particles. These deposits indicate facies that are more proximal than those encountered in the underlying Saint-Vaast Chalk Formation. The global eustatic level, as defined by Haq (2014), reveals a low stand interval in the early Santonian, which aligns well with the depositional facies observed in the lower part of the Trivières Chalk Formation and the stratigraphic hiatus revealed by stratigraphic studies in the Mons Basin (Robaszynski et al., 2001), northern France and southern England (Gale, 2024). Within the upper Santonian of the Anglo-Paris Basin, hardgrounds are locally developed in the condensed successions found in phosphate basins in the chalk. Surfaces of condensation, such as in the interval corresponding to the lower part of the Trivières Chalk Formation, often mark sequence limits in terms of sequence stratigraphy in chalk (Godet et al., 2023). The base of the lower part of the Trivières Chalk Formation is marked by a decimeter to pluri-decimeter thick conglomerate that spans the entire Mons Basin. From the Aptian to the Late Cretaceous, the subsidence in the Mons Basin was primarily linked to karstic phenomena and the dissolution of Viséan anhydrite layers, which were oriented east-west (Quinif et al., 1997; Vandycke & Spagna, 2012). Following this initial phase of karstic subsidence, the subsidence of the Mons Basin intensified from the Santonian onwards, mainly due to extensional crustal tectonics (Vandycke et al., 1991). The gravity flow at the base of the Trivières Chalk Formation may have been affected by this increase in tectonic activity, potentially causing local earthquakes and destabilizing the sediments on the platform and within the whole basin.

-

Upper part of the Trivières Chalk Formation

48Within the Trivières Chalk Formation, depositional facies and hiatal surfaces form sedimentary cycles such as those described by Lasseur et al. (2009). The water depth profile provided by these authors suggests that the Trivières Chalk Formation was deposited in an offshore environment, around the storm wave base limit. The storm wave base, defined as the water depth below which storm-induced deposition is absent, was identified at the transition from DF5 to DF6 by Lasseur et al. (2009). In terms of sequence stratigraphy, in the Trivières Chalk Formation, the DF6 defines a maximum flooding surface at the limit Santonian–Campanian. The deposits then show no signs of current activity, and primarily consist of mudstone facies, where shell accumulations are no longer evident. These facies are associated with deep-ramp / lower offshore environments.

49The presence of deformation bands suggests the occurrence of synsedimentary tectonic activity during the deposition of Trivières Chalk Formation (see Section 5.2.). The ramp slope may also have become steeper due to the increasing basin subsidence during the Santonian (Vandycke et al., 1991), which likely promoted gravity flows resulting in conglomerate deposition. The gravity flow processes may also explain the significant thickness difference of the Trivières Chalk Formation between D2 and D3. Indeed, one can imagine that D2, being located further north, is located slightly higher on the platform and that the debris flow takes material from that area to redeposit it lower, around the D3 area, where numerous conglomeratic episodes are identified. Notably, in the Trivières Chalk Formation of D2, no gravitational deposits are identified, but deformation bands attest to early destabilization of the sediments. However, the variations in thickness could also come from channelized structures or differential deposits related to paleotopography and bottom currents. Core observations alone are not sufficient to support one hypothesis over the other. Access to the outcrop field or the acquisition of seismic data would be necessary.

-

Obourg Chalk Formation

50The base of the Obourg Chalk Formation is marked by a phosphatic conglomerate layer and a stratigraphic hiatus (Robaszynski et al., 2001 and Fig. 1). Extensive petrographic and geochemical observations by Richard et al. (2005) indicate that lithification is a seafloor process occurring at and near the sediment-seawater interface. This hardground marks the base of a major transgressive sequence that reflects a change in the face of the Mons Basin and the emerging Rhenish Massif. The marine transgression that begins at the start of the Campanian will result in the deposition of white chalk formations, starting with the Obourg Chalk Formation, and followed by the Nouvelles Chalk and Spiennes Chalk formations (Robaszynski et al., 2001). Until then, the Mons Basin likely remained a microenvironment, with ecological niches linked to its peculiar paleogeography and its proximity to the landmass of the Rhenish Massif. The sea-level variations during the Late Cretaceous period have been the subject of numerous reconstructions (Ruban, 2015). However, a significant transgression at the beginning of the Campanian is widely recognized in first-order eustatic cycles (Kominz et al., 2008; Müller et al., 2008; Haq, 2014). The Campanian transgression flooded all the remaining emerged lands in Northwestern Europe and reflects the culmination of the Chalk Sea with deposits of white chalks, as defined sensu stricto, almost entirely made up of coccolith fragments and nanofossils, across the entire northern Europe (Thibault et al., 2016).

Figure 13. Depositional environment reconstruction for each formation. Abbreviations: SWB, storm wave base; P, phosphorus.

5.2. Deformation bands

51The presence of deformation bands can be correlated with the fracture intensity computed for each borehole, as reported by Descamps et al. (2020). The fracture intensity is quantified as 0.5 fractures/m in D1, 1.36 fractures/m in D3, and 1.74 fractures/m in D2. Notably, D2, which is characterized by a higher number of fractures, particularly faults, exhibits a greater number of deformation bands. In contrast, D1, which is less impacted by natural fractures, shows no evidence of deformation bands. D3, with an intermediate fracture intensity, displays a corresponding intermediate occurrence of deformation bands. D2 is located 300 m north of the other two drill holes, closer to the margin of the basin, near a major fault network that delineates the northern boundary of the Mons Basin. This normal fault system was active and extensional at the time of chalk deposition. It can be postulated that the proximity of this fault network increased the likelihood of deformation band development. Indeed, Gaviglio et al. (2009) demonstrated that these features were present in the fault damage zone, in the white chalk of the Mons Basin. A recent study on sandstones also suggested that normal faults and steeply dipping deformation bands with similar orientation are caused by the same extensional stress regime (Swanger et al., 2023). The latter authors suggested that the rock shows two different yet potentially simultaneous strain responses: plastic yielding (reflected by the deformation bands) and brittle failure (inducing normal faulting). Furthermore, some studies suggested that deformation bands represent local pore space collapse and do not classify as natural fractures. They are considered structural discontinuities that formed early as the sediment underwent compaction (Wennberg et al., 2013; Minde & Hiorth, 2020). In the context of our study, deformation bands are primarily concentrated in D2 (and to a lesser extent in D3) and only affect the Trivières Chalk Formation. The features are likely linked to a more active synsedimentary tectonic activity during Trivières Chalk Formation deposition. However, they might also develop later, but tend to form preferentially in this Formation, due to its specific mechanical properties that remain to be defined. To understand the intricate interplay of synsedimentary extensive tectonics and compaction in the formation of the deformation bands within the Trivières Chalk Formation, further research is necessary. It is therefore recommended that an in-depth investigation of deformation bands should be performed across all chalk formations throughout the entire Mons Basin.

6. Conclusion

52This study offers an in-depth examination of Coniacian to Campanian chalk from three adjacent cored drill holes in the Mons Basin, transecting the lower part of Obourg Chalk, Trivières Chalk, Saint-Vaast Chalk, and Maisières Chalk formations. Three unique sedimentary logs, totaling 350 m of chalk, were examined using petrographic analysis and microtextural observations, leading to the following conclusions:

-

Evidence of phosphatization, silicification, glaucony and pyrite formation was found in two key stratigraphic levels, namely the Maisières Chalk Formation and the lower part of the Trivières Formation, suggesting hypo- to anoxic conditions.

-

Upwelling currents were identified as the probable source of phosphatization and the cause for condensed chalk intervals by winnowing of fine particles.

-

Deformation bands and conglomeratic chalk layers were identified in the Trivières Chalk Formation, which were linked to synsedimentary tectonic activity within the basin during the early Campanian.

-

Depositional environments along the carbonate platform were reconstructed based on depositional facies. The transgressive and regressive cycles, as well as depositional hiatus, were identified in terms of sequence stratigraphy.

53In summary, the research addresses various phenomena, including marine currents, sea-level changes, and tectonic activity, that influenced chalk deposition in the Mons Basin. These insights enhance our understanding of the geological and sedimentological characteristics of the Mons Basin and the factors influencing chalk deposition during the Late Cretaceous.

Acknowledgment

54The authors would like to thank SMETS for their excellent work in producing quality chalk cores. The project was part of a research studies consortium between Holcim, Jan de Nul, and UMONS. We thank A. Gale,F. Amédro and an anonymous reviewer for their constructive reviews. We are deeply appreciative of Holcim for granting us access to the cores. Special thanks to our technician, Damien Bury, for his invaluable assistance throughout this project. We would also like to acknowledge that authors Ophélie Faÿ and Sara Vandycke are respectively a postdoctoral researcher and a research associate of the FNRS (Belgium).

Author contributions

55SV organized the project, supervised the coring and sampling. FD participated in the coring investigation. OF and SV conducted the sedimentological logging and description of the cores. OF, HC and RS performed the sedimentological analysis from microfacies and contributed to the scientific discussion. FD supervised the mechanical and petrophysical analysis. OF wrote the manuscript, while OF and RS prepared the figures. SV contributed their long-standing expertise on the Mons Basin geological context and significantly improved the manuscript.

Data availability

56The three cores are the property of the local cement industry. The studied samples are stored at the University of Mons (UMONS). The detailed sedimentological logs at a 1:10 scale are available upon request from the corresponding author.

References

57Abdallah, Y., Sulem, J., Bornert, M., Ghabezloo, S. & Stefanou, I., 2021. Compaction banding in high‐porosity carbonate rocks: 1. Experimental observations. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 126/1, e2020JB020538. https://doi.org/10.1029/2020JB020538

58Amédro, F., Graveleau, F., Hofmann, A., Trentesaux, A. & Tribovillard, N., 2023. La craie glauconieuse de Lezennes et ses « Tuns » dans le forage de la Cité Scientifique de Villeneuve d’Ascq (Nord) : interprétation d’une succession ultra condensée à la limite Turonien-Coniacien. Annales de la Société Géologique du Nord, 30, 49–78.

59Amédro, F., Deconinck, J.-F. & Robaszynski, F., 2025. The Cretaceous deposits of the Paris Basin. Geological Society, London, Special Publications, 545, 13–34. https://doi.org/10.1144/SP545-2023-90

60Aydin, A. & Johnson, A.M., 1978. Development of faults as zones of deformation bands and as slip surfaces in sandstone. Pure and applied Geophysics, 116, 931–942.

61Baele, J.-M., Godefroit, P., Spagna, P. & Dupuis, C., 2012. A short introduction to the geology of the Mons Basin and the Iguanodon Sinkhole, Belgium. In Godefroit, P. (ed.), Bernissart Dinosaurs and Early Cretaceous Terrestrial Ecosystems. Indiana University Press, Bloomington, Life of the Past, 35–42.

62Banerjee, S., Farouk, S., Nagm, E., Choudhury, T.R. & Meena, S.S., 2019. High Mg-glauconite in the Campanian Duwi Formation of Abu Tartur plateau, Egypt and its implications. Journal of African Earth Sciences, 156, 12–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jafrearsci.2019.05.001

63Bansal, U., Pande, K., Banerjee, S., Nagendra, R. & Jagadeesan, K.C., 2019. The timing of oceanic anoxic events in the Cretaceous succession of Cauvery Basin: Constraints from 40Ar/39Ar ages of glauconite in the Karai Shale Formation. Geological Journal, 54/1, 308–315. https://doi.org/10.1002/gj.3177

64Briart, A. & Cornet, F.-L., 1880. Descriptions des fossiles du calcaire grossier de Mons. Troisième partie. Supplément aux deux premières parties. Mémoires de l’Académie royale des Sciences, des Lettres et des Beaux-Arts de Belgique, 43/1, 1–80.

65Carson, G.A. & Crowley, S.F., 1993. The glauconite-phosphate association in hardgrounds: examples from the Cenomanian of Devon, southwest England. Cretaceous Research, 14/1, 69–89. https://doi.org/10.1006/cres.1993.1006

66Christensen, W.K., 1999. Upper Campanian and Lower Maastrichtian belemnites from the Mons Basin, Belgium. Bulletin de l’Institut royal des Sciences naturelles de Belgique, Sciences de la Terre, 69, 97–131.

67Colbeaux, J. P., 1974. Mise en évidence d’une zone de cisaillement nord-artois. Comptes Rendus hebdomadaires des séances de l’Académie des Sciences, Série D : Sciences naturelles, Paris, 278, 1159–1161.

68Cornet, F.-L. & Briart, A., 1866. Description minéralogique, paléontologique et géologique du terrain crétacé de la province de Hainaut : Mémoire couronné par la Société des Sciences, des Arts et des Lettres du Hainaut (concours de 1863-1864). Dequesne-Masquillier, Mons, 199 p.

69Cornet, J., 1922. V. The Cretaceous and Tertiary formations of the Mons District. Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association, 33/1, 26–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-7878(22)80016-X

70Descamps, F., Faÿ-Gomord, O., Vandycke, S., Gonze, N. & Tshibangu, J.-P., 2020. Connecting engineering properties of chalk to geological logging. In ISRM International Symposium - EUROCK 2020. p. ISRM-EUROCK-2020-039.

71Dunham, R.J., 1962. Classification of carbonate rocks according to depositional texture. Memoir of American Association of Petroleum Geology, 1, 108–121

72Dupuis, C. & Robaszynski, F., 1986. Tertiary and Quaternary deposits in and around the Mons Basin, documents for a field trip. Mededelingen van de Werkgroep voor Tertiaire en Kwartaire Geologie, 23/1, 3–19.

73Dupuis, C. & Vandycke, S., 1989. Tectonique et karstification profonde : un modèle de subsidence original pour le Bassin de Mons. Annales de la Société géologique de Belgique, 112/2, 479–487.

74Faÿ-Gomord, O., Soete, J., Katika, K., Galaup, S., Caline, B., Descamps, F., Lasseur, E., Fabricius, I.L., Saiag, J., Swennen, R. & Vandycke, S., 2016. New insight into the microtexture of chalks from NMR analysis. Marine and Petroleum Geology, 75, 252–271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2016.04.019

75Faÿ-Gomord, O., Verbiest, M., Lasseur, E., Caline, B., Allanic, C., Descamps, F., Vandycke, S. & Swennen R., 2018. Geological and mechanical study of argillaceous North Sea chalk: Implications for the characterisation of fractured reservoirs. Marine and Petroleum Geology, 92, 962–978. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2018.03.037

76Flexer, A. & Reyment, R.A., 1989. Note on Cretaceous transgressive peaks and their relation to geodynamic events for the Arabo-Nubian and the Northern African shields. Journal of African Earth Sciences, 8, 65–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0899-5362(89)80010-7

77Gale, A.S., 2024. Correlation of the Coniacian and Santonian stages of the Upper Cretaceous in the Anglo-Paris Basin. Acta Geologica Polonica, 74/2, e8. https://doi.org/10.24425/agp.2024.150001

78Gaviglio, P., Bekri, S., Vandycke, S., Adler, P. M., Schroeder, C., Bergerat, F. & Coulon, M., 2009. Faulting and deformation in chalk. Journal of Structural Geology, 31/2, 194–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsg.2008.11.011

79Georgieva, T., Descamps, F., Gonze, N., Vandycke, S., Ajdanlijsky, G. & Tshibangu, J.-P., 2023. Stability assessment of a shallow abandoned chalk mine of Malogne (Belgium). European Journal of Environmental and Civil Engineering, 27/6, 2358–2372. https://doi.org/10.1080/19648189.2020.1762752

80Godet, A., Suarez, M.B., Price, D., Lehrmann, D.J. & Adams, T., 2023. Paleoenvironmental constraints on shallow-marine carbonate production in central and West Texas during the Albian (Early Cretaceous). Cretaceous Research, 144, 105462. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cretres.2022.105462

81Godfriaux, I. & Sigal, J., 1969. Les foraminifères de la craie de Maisières et de la craie de Saint-Vaast (bassin Crétacé de Mons). Bulletin de la Société belge de Géologie, de Paléontologie et d’Hydrologie, 78/3-4, 187–190.

82Gräfe, K.-U., 1999. Foraminiferal evidence for Cenomanian sequence stratigraphy and palaeoceanography of the Boulonnais (Paris Basin, northern France). Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 153/1-4, 41–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0031-0182(99)00080-2

83Haq, B.U., 2014. Cretaceous eustasy revisited. Global and Planetary change, 113, 44–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloplacha.2013.12.007

84Ineson, J.R., Lauridsen, B.W., Lode, S., Sheldon, E., Sørensen, H.O., Wisshak, M. & Anderskouv, K., 2022. A condensed chalk–marl succession on an Early Cretaceous intrabasinal structural high, Danish Central Graben: Implications for the sequence stratigraphic interpretation of the Munk Marl Bed. Sedimentary Geology, 440, 106234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sedgeo.2022.106234

85Ineson, J.R., Stemmerik, L. & Surlyk, F., 2005. Chalk. In Selley, R.C, Cocks L.R.M. & Plimer, I.R. (eds), Encyclopedia of Geology, Volume 5. Elsevier, Oxford, 42–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/B0-12-369396-9/00307-5

86Jarvis, I., 1980. The initiation of phosphatic chalk sedimentation – The Senonian (Cretaceous) of the Anglo-Paris Basin. The Society of Economic Paleontologists and Mineralogists, Special Publications, 29, 167–192. https://doi.org/10.2110/pec.80.29.0167

87Jarvis, I., 1992. Sedimentology, geochemistry and origin of phosphatic chalks: the Upper Cretaceous deposits of NW Europe. Sedimentology, 39, 55–97. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3091.1992.tb01023.x

88Jarvis, I., 2006. The Santonian–Campanian phosphatic chalks of England and France. Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association, 117/2, 219–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-7878(06)80011-8

89Jørgensen, L.N., 1992. Dan Field – Denmark, Central Graben, Danish North Sea. In Foster, N.H. & Beaumont, E.A. (eds), Atlas of Oil and Gas Fields. Structural Traps VI. American Association of Petroleum Geologists, Tulsa, 199–218.

90Kennedy, W.J., 1987. Late Cretaceous and early Palaeocene Chalk Group sedimentation in the Greater Ekofisk area, North Sea central graben. Bulletin des Centres de Recherches Exploration-Production Elf- Aquitaine, 11/1, 91–126.

91Kominz, M.A., Browning, J.V., Miller, K.G., Sugarman, P.J., Mizintseva, S. & Scotese, C.R., 2008. Late Cretaceous to Miocene sea‐level estimates from the New Jersey and Delaware coastal plain coreholes: An error analysis. Basin Research, 20/2, 211–226. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2117.2008.00354.x

92Ladant, J.B., Poulsen, C.J., Fluteau, F., Tabor, C.R., MacLeod, K.G., Martin, E.E. & Rostami, M.A., 2020. Paleogeographic controls on the evolution of Late Cretaceous ocean circulation. Climate of the Past, 16/3, 973–1006. https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-16-973-2020

93Lasseur, E., Guillocheau, F., Robin, C., Hanot, F., Vaslet, D., Coueffe, R. & Neraudeau, D., 2009. A relative water-depth model for the Normandy Chalk (Cenomanian–Middle Coniacian, Paris Basin, France) based on facies patterns of metre-scale cycles. Sedimentary Geology, 213, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sedgeo.2008.10.007

94Lauridsen, B.W. & Surlyk, F., 2008. Benthic faunal response to late Maastrichtian chalk–marl cyclicity at Rørdal, Denmark. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 269/1-2, 38–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2008.07.001

95López-Quirós, A., Escutia, C., Sánchez-Navas, A., Nieto, F., Garcia-Casco, A., Martín-Algarra, A. & Salabarnada, A., 2019. Glaucony authigenesis, maturity and alteration in the Weddell Sea: An indicator of paleoenvironmental conditions before the onset of Antarctic glaciation. Scientific reports, 9, 13580. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-50107-1

96Marlière, R., 1967. Carte géologique de la Belgique à l’échelle 1/25 000. Texte explicatif de la feuille Mons-Givry, n° 151. Hayez, Bruxelles, 71 p.

97Marlière, R., 1970. Géologie du bassin de Mons et du Hainaut : Un siècle d’histoire. Annales de la Société géologique du Nord, 4, 171–189.

98Mendenhall, M.H., Henins, A., Hudson, L.T., Szabo, C.I., Windover, D. & Cline, J P., 2017. High-precision measurement of the x-ray Cu Kα spectrum. Journal of Physics B: Atomic, Molecular and Optical Physics, 50/11, 115004. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6455/aa6c4a

99Minde, M.W. & Hiorth, A., 2020. Compaction and fluid—rock interaction in chalk insight from modelling and data at pore-, core-, and field-scale. Geosciences, 10, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences10010006

100Moorkens, T.L., 1969. Quelques Globotruncanidae et Rotaliporidae du Cénomanien, Turonien et Coniacien de la Belgique. In Brönnimann, P. & Renz, H.H. (eds), Proceedings of the First International Conference on Planktonic Microfossils, Geneva 1967, Vol. 2. E.J. Brill, Leiden, 435–459.

101Mortimore, R.N., Gallagher, L.T., Gelder, J.T., Moore, I.R., Brooks, R. & Farrant, A.R., 2017. Stonehenge–a unique Late Cretaceous phosphatic Chalk geology: implications for sea-level, climate and tectonics and impact on engineering and archaeology. Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association, 128/4, 564–598. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pgeola.2017.02.003

102Müller, R.D., Sdrolias, M., Gaina, C., Steinberger, B. & Heine, C., 2008. Long-term sea-level fluctuations driven by ocean basin dynamics. Science, 319/5868, 1357–1362. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1151540

103Muscente, A.D., Michel, F.M., Dale, J.G. & Xiao, S., 2015. Assessing the veracity of Precambrian ‘sponge’ fossils using in situ nanoscale analytical techniques. Precambrian Research, 263, 142–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.precamres.2015.03.010