- Accueil

- Numéro 2

- Articles

- Public policies for audiovisual preservation in Brazil and the Cinemateca Brasileira crisis

Visualisation(s): 40382 (4 ULiège)

Téléchargement(s): 88 (0 ULiège)

Public policies for audiovisual preservation in Brazil and the Cinemateca Brasileira crisis

Document(s) associé(s)

Version PDF originaleRésumé

Considérant les politiques publiques brésiliennes pour la culture, nous avons passé en revue les lois des années 1940 à 2019 pour comprendre les politiques publiques de préservation de l'audiovisuel. Les très rares découvertes faites dans les lois et la littérature académique ont confirmé notre argument principal : il existe des politiques pour le secteur du patrimoine mais pas une intersection entre l'audiovisuel et le patrimoine pour aboutir à une politique publique de préservation de l'audiovisuel. Gardant cela à l'esprit, nous avons également étudié la Cinemateca Brasileira en tant qu'institution centrale du domaine audiovisuel. Elle est devenue une institution fédérale en 1984 et a traversé diverses crises, jusqu'à sa fermeture en janvier 2020.

Abstract

Considering the Brazilian public policies for culture, we reviewed laws from 1940’s until 2019 to understand public policies for audiovisual preservation. The very few findings in laws and academic literature have confirmed our main argument that there are policies for the heritage sector but what does not exist is an intersection between audiovisual and heritage to result in an audiovisual preservation public policy. Bearing that in mind, we also studied the Cinemateca Brasileira as a core institution to the audiovisual field. It became a federal institution in 1984 and went through various crisis, until its shut down in January 2020.

Table des matières

Introduction

1In order to understand why there are no specific federal public policies for audiovisual preservation in Brazil, we have highlighted some elements as well as some institutions that deal with audiovisual collections such as Arquivo Nacional (The National Archives), Cinemateca Brasileira (Brazilian Cinemateque), Museu Nacional (National Museum) and Museu de Arte Moderna do Rio de Janeiro (The Museum of Modern Art of Rio de Janeiro).

2

3Our main argument is that, without the participation of the heritage sector, the audiovisual preservation domain will likely stay out of public policies for culture and heritage, even though there is an urgency to address audiovisual as heritage in the country’s cultural scenario. To name a couple of reasons for this pressing theme, most institutions maintain audiovisual pieces either as part of collections or part of their reference documents; also, besides that, audiovisual production have become a democratic tool to express artistic views and register social events that will unavoidably reflect on how public policies, countries and society look at themselves in the future.

4

5As our main references, we have read and analysed legal documents and more specifically federal laws that would mention cinema, film and audiovisual in search of specifics on preservation. We have also read and analysed public policies for culture and heritage, crossing references that would lead to audiovisual preservation. The very few findings in legal documentation from 1940’s to 2019 confirmed the relevance of our argument to bring the subject to the museum studies perspectives in the hopes to shed light on overlooked collections both in and out of museums and memory institutions. For specific contents on the history of Cinemateca Brasileira, the works of Calil (1981) and Souza (2009), as well as the institutions reports as primary documents, were essential for creating a timeline of events. We have also conducted two interviews with key professionals closely related to the cinemateque’s existence: Antonio Carlos Calil, Professor at the University of São Paulo (USP) and member of the Sociedade Amigos da Cinemateca, a non-profit organization (NPO) institution that has just signed the contract to manage the Cinemateca Brasileira starting in January 2022; and Fernanda Coelho, teacher at the Fundação Escola de Sociologia e Política de São Paulo (FESPSP) and preservationist at the Cinemateca Brasileira for over 20 years.

6

7Our literature review also included academic works in the fields of Public Policy, Social Memory, History, Visual Arts, Cinema, Communication, Museum Studies, and Information Science to conclude that very few studies have been done so far to discuss the lack of public policies for audiovisual preservation and even less within the heritage and museum field studies. Our opinion is that the subject has been well studied under an art form in Cinema Studies and as historical document under History, for example. Apparently, unfortunately, museum studies have not been concerned about audiovisual collections and its preservation under a more political perspective.

8

9The scope of our readings has extended our research to international organizations such as The International Federation for Archive Film (Fiaf), International Museum Council, (Icom) and Unesco (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization), to bring what happens in Brazil into an international context (Correa, 2009), as well as to demonstrate that international documents and standards do exist, but they are not easily applied, even considering the fact that Brazil is an active member of renowned institutions as Unesco, the Brazilian Institute of Museums (Ibram), Icom, the Cinemateca Brasileira, and Fiaf.

10

11During our master’s research, from 2018 to 2020, it was also possible to review Bourdieu’s (2007) field theory: for the author, the maintenance and perpetuation of political power would occur through the consecration field, which is distinct from the production field; here, in this case, cinema production. Certeau’s discussions (1984) on tactics and strategies was helpful to point out agents who played a part into the cinemateque’s history and public policies for audiovisual preservation.

12

Federal institutions and their audiovisual archives: an overview

13Brazilian federal entities have been involved with audiovisual production and archives since the first film productions, in 1898. Museums, archives, and other heritage and collection institutions have developed few and isolated policies for audiovisual preservation while producing and safeguarding audiovisual documents for needs related to their core activities, for example, educational purposes. However, unfortunately, that has not been enough to create specific federal public policies for audiovisual preservation. We would like to demonstrate that, in Brazil, throughout the decades, audiovisual documents have not been included into discussions of preservation and restoration as part of relevant collections for heritage and memories. Besides that, audiovisual preservation has not been addressed in public policies for audiovisual either. As a result, there is a lack of policies to protect and preserve what we understand as an important cultural representation of the 20th century societies.

14

15In Brazil, the first institution created to guard heritage collections is the National Museum, in 1818. Between the years of 1900 to 1913, the Rondon Commission traveled throughout the interior of Brazil and, from 1907 to 1915 and Edgard Roquette-Pinto1 registered the Nambiquara ethnic group, from 1912 to 1913, bringing to the Museum 2.156 objects, including “many meters of ethnographic films” (Santos, 2020).

16

17For Souza (2009), however, the film collection was a personal one. If this was the case, Roquette-Pinto's personal collection went to Embrafilme's Direction of Non-Commercial Operations. In 1980, this collection migrated to the Museum of Cinema at Funarte (The National Foundation of the Arts, an agency attached to the Ministry of Tourism nowadays). The Funarte collection went to the Museum of Modern Art of Rio de Janeiro (MAM-RJ), a private museum that has a cinemateque found in 1951.

18

19In 1946, the National Museum was transferred to the Rio de Janeiro Federal University. On September 2nd, 2016, the main building and most of its collections burned down in a fire hazard that last over 4 hours.

20

21The National Archive was founded in 1838 and in 1893 it became part of the Ministry of Justice and Internal Affairs. Over the decades, it gathered the Department of Audiovisual Documents (1975); the Technical Chamber of Audiovisual, Iconographic, Sound and Music Documents (2010); and it has produced international film festivals, the Recine festival in 2002 and the Arquivo em Cartaz since 2015. In 2019, the collection contains 50 thousand cans of film, including 8mm, Super-8, 16mm, 35mm, videotapes and digital formats, being the second largest moving images collection in Brazil, after the Cinemateca Brasileira with 250 thousand rolls of films (Ministério da Justiça, 2019).

22

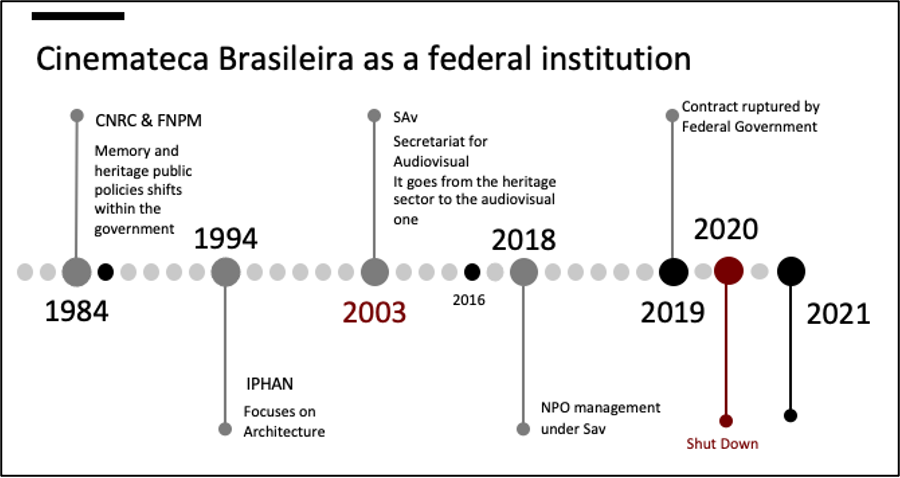

23The Cinemateca Brasileira was created in 1949 as a private institution and went through numerous institutional configurations until it became part of the federal organization in 1984, attached to the National Pro-Memory Foundation (FNPM) of the Ministry of Education and Culture (MEC). In 1992, with the recreation of the Ministry of Culture (MinC), the Cinemateca Brasileira joined the Institute of National Historical and Artistic Heritage, Iphan. In 2003, still under the Federal Government, it was joined to the Audiovisual Secretariat (SAv). In 2018, MinC signed a management contract with the Roquette Pinto Educational Communication Association (Acerp)2, a non-profit organization specialized in culture management. In 2019, the contract with Acerp was not renewed and in 2020, amid the covid-19 pandemic, the Cinemateca Brasileira's activities were paralyzed, workers were laid off with wage arrears. In June 2021, a fire took one of its deposit holding the film copies and paper documents.

24

25Amongst all its turmoils, the institution was able to become the most important cinemateque in South America, developing creative processes for film preservation, exchanging collections, and working with other institutions and professionals for its almost 50 years of existence. Nowadays, it holds around 250 thousand film rolls and close to one million documents of films, its directors, film critiques and so on. Since 1993 up to this date, it is the only legal depository for films produced with federal foment and subsidies. Before the Legal Depository Law, movies were archived by their producers, some at the MAM-RJ. Most of Brazil’s public policy for audiovisual preservation goes with the history of the Cinemateca Brasileira, as we point out in the next lines.

26

27In 1985, the Technical Audiovisual Center (CTAv) was created linked to Embrafilme3. CTAv had responsibilities for audiovisual conservation and preservation, besides film production. We believe CTAv was as an attempt to bridge the gap between the State and experimental and non-commercial production, since the production and distribution of commercial films were already responsibilities of Embrafilme. By doing so, it would compensate the decrease on film productions by Embrafilme in the mid 1980’s due to the United States’ market imposition on better quality. Embrafilme was becoming noncompetitive in the market thanks to the technical progress of United States cinema and its aggressiveness in conquering markets in Latin America. The Sarney Law, in 1982, is also another factor, since it forces Embrafilme to supplement its budget with external funds, competing with other areas related to the arts for the financing of its productions (Silveira; Carvalho, 2016). The CTAv archives have films produced by several institutes and agents attached to the federal government that no longer exist, such as Embrafilme, and they also have archived custody films deposited by producers and directors. Most of the collection is composed of 16 and 35mm film. There are also films in other supports, such as U-Matic and Betacam.

28

Attempts of public policies for audiovisual preservation: endless restarts

29Federal policies regarding culture have barely included audiovisual preservation even though Brazil has had cultural policies since the 1940’s. Bezerra (2013) believes there are three main factors for the situation of audiovisual preservation in the country as: the status of culture in public policies; then, the space for heritage within the policy for culture and, finally, the privileged matters within film policies such as production foment, for example (Bezerra 2013, p. 3).

30

31Calabre (2009) brings the Vargas Era (1930-1945 to show that a set of actions became cultural policies. The Department of Culture of the city of São Paulo, with Mario de Andrade, in 1935, creates the first audiovisual preservation city law, regulating the deposit of São Paulo’s film production to the City Department of Culture. This specific city law did not have continuity in time, as most laws in the sector. Getúlio Vargas Era divides film policies into three groups: educational, regulatory (with stimulus to private initiative production) and indoctrination (cine-journals of the Department of Propaganda and Cultural Dissemination). As for the heritage sector, in 1934, it creates the National Historical and Artistic Heritage Service, Sphan, that will become the Iphan of today.

32

33The Military Governments (1964-1985) culture policies aim for public policies that would have a uniform view of the Brazilian culture. Cinema policies were for educational and propaganda purposes. Cinema production was regulated primarily aiming to control and censor. There were also policies for the heritage sector, specifically the historical archaeological, ethnographic, bibliographic, and artistic value. What did not exist and still does not is an intersection of these two fields for film preservation.

34

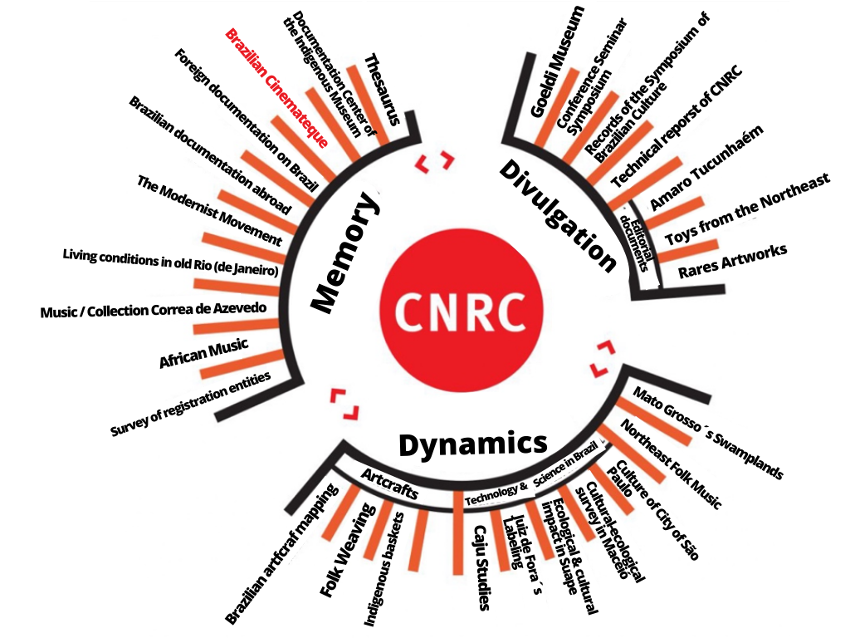

35The idealization of a convergence of both the audiovisual and the heritage sector took place in 1975, in Aloísio Magalhães' draft for the National Center of Cultural Reference (CNRC). The Center was maintained by an agreement between the Ministries of Industry and Commerce, Education and Culture with the Interior and Foreign Affairs – among other federal institutions – and the Federal District Government. Magalhães thought of designing the CNRC with 3 axes: memory (research, registration, and archiving of cultural practices), dynamics (studies and analysis of activities), and divulgation (insertions that encouraged reflections and improvements in each cultural context composing the stages or phases of each project) (Figure 1). The Cinemateca Brasileira would be under the field of memory showing that Magalhães suggested a different design of cultural policy from the existing laws of the time. The idea, however, did not get off the drawing board, leaving film preservation out of the heritage public policies up to this date and the Cinemateca Brasileira out of the federal sphere for another ten years.

36

Figure 1 – Diagram of CNRC by Aloísio Magalhães.4

37

38Following that, the New Federal Constitution of 1988 replaced the concept of Historical and Artistic Heritage to Brazilian Cultural Heritage. Iphan reformed its management practices for this new understanding of cultural heritage, but the audiovisual heritage was not included in the Institute’s practices even though the Cinemateca Brasileira was under its coordination from 1995 until 2003.

39

40Then, Fernando Collor becomes Brazil’s president in 1990 and shuts down MinC, establishing the National Program of Cultural Support (Pronac) and the standardization for the National Culture Fund (FNC). The Pronac’s objective was to capture and channel resources for culture, preserve material and immaterial assets of cultural and historical heritage through the FNC. However, unfortunately, none of these creations achieved the preservation of audiovisual collections in their ways of promoting or managing cultural heritage.

41

42In 1992, under the government of President Itamar Franco, the Ministry of Culture resurfaces, and with it, the Audiovisual Secretariat (SAv) was created. The new Secretariat was based on a proposition of national policies for cinema and audiovisual, including the preservation and dissemination of content.

43

44The 1993 Audiovisual Law had created the legal deposit obligation for the Cinemateca Brasileira. As we have already mentioned, to this day, the Cinemateca Brasileira is the only institution accredited to receive audiovisual productions made with federal funding. All productions that received money from federal institutions (including federal banks, federal companies such as Petrobras) must present final accounts proving that a copy from the final production is deposited at the Cinemateca Brasileira.

45

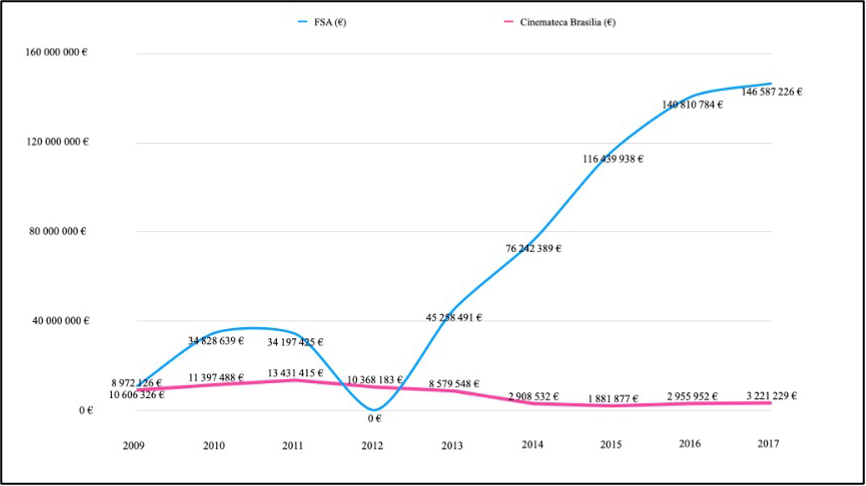

46Bearing that in mind, the absence of public policies for preservation became clearer with the advent of the Audiovisual Sector Fund (FSA), a fund created in 2006 by tax collection and collected from all audiovisual windows5. As showed in the graphic6 (Fig. 2), there is a visible investment gap between the production and the preservation of these same films. The numbers confirm that investment should also come from the heritage sector, just as State museums receive.

47

Figure 2 – Graph comparing Cinemateca Brasileira and Fundo Setorial Audiovisual budgets between 2009 to 2017 (Menezes 2019, p. 99). Euro conversion done by the author.

48

49In 2000, the federal government created the National Film Agency (Ancine), linked to the Ministry of Industry and Commerce while SAv articulated the National Plan for Film Conservation, whose goal was to create the Brazilian policy for the preservation of the moving image collection. One of its actions was to prepare the Diagnosis of the Brazilian Cinematographic Collection in the Cinemateca Brasileira and the Cinemateca do Museu de Arte Moderna do Rio de Janeiro, MAM-RJ. That could point to the intentions of taking the Cinemateca Brasileira from the Heritage Institute to the Audiovisual Secretary. And so it was done. In the following year, Iphan launched the National Museum Policy (PNM), which establishes the conceptual guidelines for the role of museums and the right to heritage, built with the participation of the museological sector from all over the country. As part of this Iphan, it would be reasonable to think that the Cinemateca Brasileira would be included into the new museum policies. Instead, in 2003, Cinemateca Brasileira was integrated into SAv with the promise of bringing modernization and investments to the field. Gustavo Dahl, president of the Ancine, defended the participation of the Cinemateca Brasileira in this new structure because he believed that preservation is a link in the audiovisual production chain. This opinion, by the way, still consists audiovisual producer’s arguments to defend the Cinemateca under the Audiovisual policies. However, generally, there is no film budget that includes its own preservation in its own financial sheets: aside from making the Legal Deposit copy that is demanded by law to films with federal money. Film production in Brazil do not split its budget with film preservation, as they should not in the current context since film preservation demands budget and policies under the heritage policies.

50

51The Cinemateca Brasileira has been an active member of the International Federation of Film Archives, Fiaf, since 1949 (Correa, 2009). As one of the first cinemateques associated in Latin America, it has established long lasting relationships with European cinemateques sharing best practices, exchanging collections, and executing preservation services, such as copy duplicates. To seal the long relationship and show support, Fiaf held its International Congress at the headquarters of the Cinemateca Brasileira, in 2006. The event was sponsored partly by the Federal Government which made possible to finish the building that the Cinemateca headquarter’s in São Paulo is placed nowadays. New building, acquiring equipments and becoming the legal deposit for Brazilian films: the first decade of 2000 brought some financial release and projects such as The Brazilian Cinema: Prospecting and Memory, a project including Brazilian Audiovisual Information System (SiBIA). Yet, due to lack of a more structural policy, the project did not finish its objectives. Still, in 2010, Cinemateca Brasileira and CTAv gave access to what they had as the Brazilian Filmography database, initiated with the SiBIA project.

52

Saving the day: two initiatives from the organized civil society

53Amid a Military Government, in 1962, the Society Friends of the Cinemateque (SAC) was founded, by Dante Ancona Lopez, the owner of a cinema theater in the city of São Paulo. SAC helped diffusing national cinema and from 600 members in 1962, to 3 thousand in 1966, it has a long-lasting partnership with the Cinemateca Brasileira, as part as the Executive Council, and it is very important in the process of re-hiring staff in 1990. In 2021, SAC has won the Federal public call to manage Cinemateca Brasileira to start in 2022.

54

55We understand SAC as an organized civil society that was fundamental in the construction of actions and projects that guaranteed the survival of the Cinemateca Brasileira.

56

57In 2008, during The Ouro Preto Film Festival, in the city of Ouro Preto, Minas Gerais state, the Brazilian Association for Audiovisual Preservation (ABPA) was created as a civil society entity with the mission to contributing to the development and improvement of audiovisual preservation professionals. These professionals meet yearly, create debates, capacity building and exchange knowledge on audiovisual preservation in Brazil and abroad. In 2016, they approved the National Plan for Audiovisual Preservation. Divided into diagnosis, objectives, actions, and goals, the plan proposed ten years for its implementation and is reviewed every three years. The 19 goals proposed include the creation of legislation, articulation among memory equipment, the presence of civil society in decision-making, events, promotion, and publication for audiovisual heritage institutions, and a specific national technical school for audiovisual preservation. ABPA was not successful into discussing the Plan with federal authorities to this day. Gathering more members every year, the Association has over 300 paying members and has gained political importance particularly after the Cinemateca’s flood and fires (2019, 2020, 2021) being called to speak, write, and dialogue about the crisis.

58

The heritage sector: Iphan and Ibram divide tasks

59As already mentioned, in 2003, the Department of Museums and Cultural Centers at Iphan inaugurates the National Museum Plan, a national law specific for museum public policies that contemplates yearly forums, creating a system database to list Brazilian museums and the foundation of a Federal Agency, Ibram. Therefore, in 2009, the federal government created Ibram, that will inherit the responsibilities of the National Museum Plan and the administration of 30 federal museums. In 2010, The fourth edition of the National Museum Forum was held by Ibram with 1,922 attendees from the areas of museology, civil society, public authorities, and representatives from Austria, Cuba, France, the Netherlands, Mexico, and Portugal. Despite carrying out museum processes within its practices, the Cinemateca Brasileira did not participate in these events nor in the discussions about public policies for audiovisual collections and preservation which clearly shows a lack of dialogue and intersections within the Ministry of Culture and its entities.

60

61The Fifth National Museums Forum in 2012 celebrated the 40th anniversary of the Santiago Table Event, originally held in Santiago, Chile. The Forum was held in Petrópolis, Rio de Janeiro, with 1,200 participants both national and international ones, from museums, universities, government, and civil society. In its third year of existence, the Ibram has established itself as the focus point for museum public policies and launched Brazil as a protagonist in multilateral spaces such as UNESCO. Brazil was the leader country to discuss and build the 2015 Recommendation for the promotion and protection of museums and collections. Adversely, while the museum public policies flourish, the Cinemateca Brasileira struggles in search for a political space in the audiovisual production field.

62

Cinemateca Brasileira: 50 years

63As we have described, the Cinemateca Brasileira is the main institution in Brazil regarding public policies for audiovisual preservation due to its attachment to the Federal Government in 1984, but also because it reunites expertise, best practices, equipment and world-renowned films from Brazil and other countries. From its beginning until 1984, it held important status as a film library, collecting and preserving films while gaining experience in film preservation techniques. During its stay in the Iphan, Federal Government budget was enough to pay professionals, but it was not an active policy maker, even though it was part of international forums and a valuable member in debates around technical and standard preservation practices. The reason to transfer the Cinemateca Brasileira to the Secretariat of Audiovisual was that it was part of the chain of production. Once that happened in 2003, the budget increased considerably but it did not resolve management and professional issues already existing such as shortage of professionals, low salaries, and equipment maintenance.

64

Figure 3 – Produced by the author, 2021. The black dots represent the fires the Cinemateque suffered; there were two previous ones: 1954 and 1969. In 2020, while closed, a flood hit part of paper documents and DVD collections.

65

66In 2013, a succession of political decisions coming from the Ministry of Culture directly affected the future of the Cinemateca Brasileira: Carlos Magalhães, director of the Cinemateca Brasileira, was fired by the then Minister of Culture, Marta Suplicy, without consulting the Cinemateca Council, that included Antonio Carlos Calil, from the Sociedade Amigos da Cinemateca. The labor force was reduced and, therefore, the activities diminished. The situation escalated until, in 2016, the Cinemateca Brasileira released a public note stating that MinC has accepted to transfer the Cinemateca from SAv to Ibram. What happened, however, was almost the opposite: between 2016 and 2017, MinC signed contracts with Acerp to carry out a preservation project.

67

68On 4 May 2018, after the Federal Coup that took President Dilma out of office in 2016, a new Advisory Board for the Cinemateca Brasileira was introduced, replacing the previous group. This new council was composed of 16 members, 8 of whom were public authority representatives and 8 from civil society and the audiovisual sector, one from Acerp among the latter. The Government also suppressed commissioned positions at the Cinemateca. Members of the previous Advisory Council sent an extrajudicial notification requesting the publication of Cinemateca’s Internal Regulations to MinC without any response to date.

69

70Upon taking up office, in January 2019, Bolsonaro suppressed MinC and gathered the Culture, Social Development, Sports, and Labour ministries into one large Ministry of Citizenship. In May, the recently created Special Culture Secretariat was transferred to the Ministry of Tourism with SAv subordinated to it.

71

72In 2020, the Government did not renew the contract with Acerp and triggered the Cinemateca’s worst crisis, exposing this management model’s problems. In general, the Non-Profit Organization receives financial transfers funds from the Government. The Federal Government, however, adopts funding constraints: the money is released monthly and according to availability on the National Treasury investment calendar, not necessarily responding to the signed contract, according to contingencies, regardless of the demands of approved projects and schedules. In addition, the precarious nature of the relationship between the employer and the institution creates a gap between the need for trained professionals and the number of people capable of specialized audiovisual preservation work. Since 1984, as a Federal institution, the Cinemateca Brasileira has never had job openings to replace retirement or shortage of technicians. The professionals are hired to complete projects and are let go once that is delivered.

73

74On June 29th, 2021, another fire hit part of the collection of the Cinemateca Brasileira at an out-of-town deposit warehouse. Since the institution did not have professionals at work, there will not be an official report. Volunteer ex-workers have gathered an unofficial list of losses which includes Glauber Rocha’s film copies, four tons of paper documents from agencies and federal entities such as Federal Government Embrafilme and collection of the film school of the University of São Paulo. The Secretary of Culture, Mario Frias, has answered the accident blaming previous governments and informing the Federal Police will be in the case to arrest the guilty ones. As of today, the only official reports are from the Fire Department and the volunteers. One year before the fire, a sewage flood had hit the same building, destroying DVD copies of films and several other documents. No official report has been done of the flood. No legal action has been moved from the Federal Government against any parties. The tragedy was an obvious one: with no professionals on site, the Federal Government had been warned by SAC, ABPA, professionals and politicians about the urgency of a contract to re-hire professionals to monitor and prevent hazards in collections. It took the Secretary of Culture one year and a half to create an open call to contract a manager to the Cinemateque.

75

Conclusions

76The multiplicity of national institutions that deal with audiovisual preservation at the federal level – Cinemateca Brasileira, The National Archive, CTAv – and the fragility of isolated initiatives that suffer at each change of government lead to the conclusion that there is no audiovisual preservation policy in Brazil. The dispersion of the attributions and responsibilities of each one causes isolation of actions and contributes to shading of activities, on one hand, and an absence of action for certain issues, on the other.

77

78We were able to apply the concept of Bourdieu's field (2007), in which social relations occur in a space of dispute in the search for legitimization of ideas and values, to demonstrate that, while public policies do not value memory and heritage, capitalist values of profit, of salable intellectual production, of art as an element of the cultural industry impose themselves in the cultural sector. Thus, the symbolic good of memory has an inferior value to the symbolic good of a feature film shown in shopping mall theaters. This status quo is maintained with the help of the cultural policies in place in Brazil to date.

79

80Michel de Certeau (1984) brings the relations between strategies and tactics of social agents. For those who already belong to the field, the strategies are for its permanence and maintenance; for those who want to belong, the newcomers, the absence of capital, of any nature, makes negotiations impossible and leaves two possibilities: to insert themselves in the field by accepting the maintenance of strategies or to subvert it by establishing tactics.

81

82In the field of cultural policies in Brazil, we scored several relevant agents for the construction of public policies for audiovisual preservation. We understand that there were strategies created for a possible segmentation of the preservation sector, isolating audiovisual preservation, evidencing a clear competition between heritage and production. In some periods, new agents brought attempts to maintain this segmentation but, in other moments, there was the establishment of tactics for the reformulation of the field. The latter, represented mostly by civil society organizations, politicians, and academics, has created spaces with the perspective of impacting the status quo until there was some change.

83

84There is also the significant issue of the loss of institutional memory of the processes with the privatization of management. The hiring of specialists exclusively for approved projects takes with them the practices and flows developed during the execution of the activities as soon as the contracts end, with no chance of a professional bond in which the technician himself is able to create solutions and respond to more perennial problems in the field. The precariousness of the bond of the employee with the institution creates a gap between the need for trained professionals and the number of people ready for such specific technical work that is audiovisual preservation.

85

86Management by Non-Profit Organizations, the solution put forward by the Government, with the justification of greater freedom and possibility of private fundraising, finds in Brazil a practical dilemma. As we have mentioned earlier, the release of funds to fulfill contracts with NPO obey contingencies according to the National Treasury budget availability. As a consequence, monthly transfer from the Government to the NPO do not match the real expenses, leaving the management always short on the execution of the proposal plan. Therefore, management by the NPO does not effectively solve the budget issue since it depends on transfers from the Government in addition to be forced to search for other sources of income even when that is not part of the management contract.

87

88At the turn of the century, initiatives were disguised as neoliberal policy, in which sustainable management was the main discussion topic for managing cultural facilities. The result of this vision is that, in practice, the Cinemateca Brasileira is deliberately left aside since its production does not bring profit. For us, the cinemateques as any other museum are entities of the heritage field, responsible for guarding collections and documents to preserve them to make them public. That makes the Cinemateca Brasileira an institution with museum processes and, therefore, close to federal entities permeating the same purposes, such as Ibram and Iphan, which discuss public policies on heritage and memory.

89

90At a time with an extremely serious sanitary crisis more than 670 thousand deaths by covid-19 in Brazil – and the extinction of cultural policies, the construction of a new Brazilian cinemateque will only be possible if organized civil society, universities, and heritage institutions are joined together to create proposals to present to the coming government to be elected in 2022.

91

Bibliographie

Bezerra Laura 2013: Políticas para a preservação audiovisual no Brasil (1995-2010) ou: para que eles continuem vivos através de novos modos de vê-los, Doctorate Thesis in Culture and Society, Universidade Federal da Bahia.

Bourdieu Pierre, 2007: A economia das trocas simbólicas. São Paulo, Perspectiva.

Calabre Lia, 2009: Políticas culturais no Brasil: dos anos 1930 ao século XXI, Rio de Janeiro, FGV.

Calil Carlos Augsuto & XAVIER Ismael (org.), 1981: Cinemateca imaginária: cinema e memória, Rio de Janeiro, Embrafilme.

Certeau Michel, 1984: The Practice of Everyday Life. Berkeley, University of California Press.

Correa Junior Fausto, 2007: Cinematecas e cineclubes: cinema e política no projeto da Cinemateca Brasileira, Master dissertation in History, UNESP.

Ibram, 2018: Caderno da Política Nacional de Educação Museal. Brasília.

Menezes Ines 2019: « O profissional atuante na preservação audiovisual », Museologia & Interdisciplinaridade, vol. 8, n° 15, Brasília: Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciência da Informação da Universidade de Brasília.

Ministério da Justiça e da Segurança Pública – Arquivo Nacional, 2019: As imagens em movimento no Arquivo Nacional. Rio de Janeiro. Available on: https://www.gov.br/casacivil/pt-br/assuntos/conselho-superior-de-cinema/2-apresentacao-arquivo-nacional_as-imagens-em-movimento-do-arquivo-nacional (accessed: 24 October 2021).

Ramos Ferñao, 2021: Nova História do Cinema Brasileiro Parte 1. São Paulo, SESC.

Rangel Jorge, 2010: Edgard Roquette-Pinto. Recife: Editora Massangana.

Santos Rita, 2020: No Coração do Brasil: a expedição de Edgar Roquette-Pinto à Serra do Norte. (M. Nacional, Ed.). Rio de Janeiro: Museu Nacional. Available on: https://www.museunacional.ufrj.br/see/docs/publicacoes/no_coracao_do_brasil.pdf (accessed: 24 October 2021).

Senna Orlando, 2015: « Novo modelo de distribuição », Revista de Cinema. Available on: http://revistadecinema.com.br/2015/10/novo-modelo-de-distribuicao/ (accessed: 23 November 2021).

Silveira Rafael & Carvalho Francione, 2016: Embrafilme X Boca do Lixo: as relações entre financiamento e liberdade no Cinema Brasileiro nos anos 70 e 80, Aurora, Revista de Arte, Mídia e Política, vol. 8, n° 24, p. 73-93. Available on: https://revistas.pucsp.br/aurora/article/view/24616 (accessed: 14 October 2019).

Souza Carlos Roberto, 2009: A Cinemateca Brasileira e a preservação de filmes no Brasil, Doctoral thesis in Computer Science, Universidade de São Paulo.

Annexes

Abbreviations in Portuguese translated to English

ABPA : Associação Brasileira de Preservação Audiovisual – Association of Brazilian Audiovisual Preservation

Acerp : Associação de Comunicação Educativa Roquette Pinto – Roquette Pinto Educational Communication Association

Ancine : Agência Nacional de Cinema – Nacional Cinema Agency

CNRC : Centro Nacional de Referência Cultural – National Center of Cultural Reference

CTAv : Centro Técnico de Audiovisual – Technical Audiovisual Center

Embrafilme : Empresa Brasileira de Filme – Brazilian Film Company

FNPM : Fundação Nacional Pró Memória – Pro-Memory National Foundation

FSA : Fundo Setoria Audiovisual – Audiovisual National Fund

Iphan : Instituto do Patrimônio Histórico e Artístico Nacional – Institute of the National Historical and Artistic Heritage

Ibram : Instituto Brasileiro de Museus – Brazilian Institute of Museums

INCE : Instituto Nacional de Cinema Educativo – National Institute for Educational Films

MAM-RJ : Museum de Arte Moderna - RJ – Museum of Modern Art of Rio de Janeiro

MEC : Ministério da Educação e Cultura – Ministry of Education and Culture

MinC : Ministério da Cultura – Ministry of Culture

PNM : Plano Nacional de Museus – National Museums Plan

Pronac : Programa Nacional de Apoio à Cultura – National Program of Culture Support

SAC : Sociedade dos Amigos da Cinemateca – Society Friends of the Cinemateque

SaV : Secretaria do Audiovisual – Audiovisual Secretary

SiBIA : Sistema Brasileiro de Informações Audiovisual – Brazilian Audiovisual Information System

Sphan : Secretaria do Patrimônio Histórico e Artístico Nacional – National Historical and Artistic Heritage Service

Abbreviations in English

NPO : Non-Profit Organization

UNESCO : United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization

Abbreviations in French translated to English

FIAF : Fédération Internationale des Archives du Film – International Federation of Film Archives

Notes

1 Edgard Roquette-Pinto (1884-1954) In 1906, he became assistant professor of Anthropology and Ethnography at the National Museum, in Rio de Janeiro and in 1926, he became his director, managing to build the largest collection of scientific films in Brazil. He remained in this position until 1935. In 1932, he founded the Revista Nacional de Educação/National Education Magazine and the Serviço de Censura Cinematográfica/Cinematographic Censorship Service. In 1937, he founded the National Institute of Educational Cinema (INCE), which he would direct until 1947. During this period, with the filmmaker Humberto Mauro, he produced about 300 documentaries. Roquette-Pinto was also one of the founders of the Brazilian Socialist Party (PSB), in 1947.

2 Acerp is a nonprofit organization that managed radio and tv stations from early 1940’s. In 1995, signed a contract with the Federal Government to manage the TV Escola channel. In 2016, the contract is signed as an annex within the contract, starting a maze of complex judicial and management issues that will directly affect the Cinemateca Brasileira.

3 Empresa Brasileira de Filmes S.A. (1969-1990) was a Brazilian state-owned mixed economy company linked to MEC to foster production and distribution of films. In the late 1980s, there was a strong campaign of opposition to the company, accused of money waste and mismanagement. It was extinguished on March 16th 1990, by the National Privatization Program of Fernando Collor de Mello's government.

4 Available on: http://www.itaucultural.org.br/ocupacao/aloisio-magalhaes/o-gestor-cultural/?content_link=2 (accessed: 19 December 2020). Translated English version by the author (October 2021).

5 In the media technical lingo, “a window is a period of exclusivity of a content in a certain media. For example, the first window for films made for theatrical release is the movie theater.” Once this first distribution pipeline is complete, the film will be exploited in other windows, as video on demand platform, for example (Senna 2015).

6 Note from the graph’s author from the original with correction: The Cinemateca Brasileira is the only institution that receives materials in Legal Deposit and, according to Bezerra (2015), its budget represents almost the totality of investments in audiovisual preservation, in the period, in the country. Thus, Menezes consider the graph a direct illustration of the unevenness of investments in audiovisual production and preservation. The graph only reaches up to 2017, because from then on, the Cinemateca Brasileira no longer published institutional reports. In 2019, under the new government, the FSA transfers were interrupted.