- Accueil

- Numéro 1

- Articles

- The SoMus Project: Close-up on Innovative Participatory Management Models in European Museums

Visualisation(s): 2548 (19 ULiège)

Téléchargement(s): 78 (0 ULiège)

The SoMus Project: Close-up on Innovative Participatory Management Models in European Museums

Document(s) associé(s)

Version PDF originaleRésumé

Society in the Museum (SoMus) est un projet de recherche dans le domaine de la Sociomuséologie. Son objectif est de définir les modèles de gestion participative de quatre musées placés dans différents pays européens. Choisis pour leurs formes innovantes et transformatrices de participation culturelle de la société, ces musées représentent un large éventail de contextes, de cultures et de défis qui nous aident à réfléchir sur le rôle des musées dans la construction de nouveaux modèles de démocratie culturelle. Cet article trouve son origine dans la conférence faite au Comité INTERCOM-FIHRM (XXIVème Conférence Générale de l'ICOM ), où les modèles créés avec les partenaires portugais et finlandais du projet ont été présentés. Que pouvons-nous apprendre des expériences audacieuses des musées SoMus ? Comment ces modèles peuvent-ils être utiles aux musées qui cherchent à améliorer leur intensité participative ?

Abstract

Society in the Museum (SoMus) is a research project in the area of Sociomuseology. Its objective is to define the participatory management models of four museums placed in different European countries. Chosen for the innovative and transforming forms of society´s cultural participation, these museums represent a wide range of contexts, cultures and challenges that help us to reflect on the role of museums in the construction of new models of cultural democracy. This article has its roots in the conference made at the INTERCOM-FIHRM Committee (XXIV ICOM General Conference ), where the models created with the Portuguese and the Finnish partners of the project were presented. What can we learn from the bold experiences of SoMus museums? How can these models be useful for museums seeking to improve their participatory intensities?

Table des matières

Introduction

In 2014, I started my post-doc project “Society in the Museum: study on cultural participation in local museums in Europe”, most known by its acronym: SoMus[1].1

2SoMus is a participatory action-research project in the area of Sociomuseology (Moutinho 2010; Sancho Querol 2013; Sancho Querol & Sancho 2015), that combines Social Sciences and Humanities with Responsible Research and Innovation (RRI) [2] and is conducted with the support of Portuguese Ministry of Science, Technology and Higher Education due to its sociocultural usefulness. The main objectives of SoMus are: to study the most transformative practices of cultural participation of society in museums, so to systematize them into new participatory management models; to define the epistemological framework, methods and practices associated to cultural participation, which at the moment, seems to us a vital function in Museology.

3

4With this objective in mind, a small team made up of one researcher, two universities (Coimbra, in Portugal, and Jyväskylä in Finland) and four local museums representing Nordic Museology (situated in Finland and Sweden) and the Mediterranean (Spain and Portugal), have been mapping their museological practices since 2014. Their focus was on the cultural participation of society in the museum, so as to define a participatory management model that is tailor-made to each case and represents the essence of their sociomuseological work and anatomy. Chosen according to a set of seven previously defined criteria[3] to represent a diverse museum sample of local and community nature, SoMus museums are mainly characterized by their diverse heritage typologies and cultural contexts, by their innovative practices of societal-cultural participation and by their interest in defining a useful management model that focuses their participatory behavior. The resulting models allow them to understand strengths and weaknesses of their daily relationship with society, but also, help explain how their innovative work takes place together with society and to evaluate the evolution of ongoing participatory processes.

5

6After four years of work generously seasoned with sparse resources and great geographical distances, but also with a great desire to pave new ways and a large dose of collective reflection between each team, the results have emerged. At stake is the capability of the museum to succeed as a citizenship and cultural democratization tool in a time when European societies need to rethink themselves in depth in order to build wholly participatory development models that are deeply useful to the management of the cultural diversity that shapes our societies.

7In this article we present the project’s structure, objectives and work methods, as well as the participatory management models that have resulted from the research made until 2018 with the Portuguese and the Finish partners. We used transformative practices to create new tools that allowed us to theorize about the possibility and potential to fade out the society-museum dichotomy. Along the way we realized that, notwithstanding the diversity of contexts, cultures, projects and own challenges of each of these museums, the models that were so far designed may be useful for other museums that wish to assess and improve their participatory quality. We note that Museology, when co-produced with the Society, has a revealing impact.

8

1. The theoretical body: three fields connected by the verb “to participate”

9The SoMus project bases its theoretical-methodological body in a concept of participation, which emerges from the exchange of ideas, principles and experiences between three lines of cultural action of collective approach, to define its work structure, its methods and objectives.

10

11These are:

-

The museology line of thought of Sociomuseology, a social science (Moutinho 2010) that derives from the maturation of the New Museology and from its adaptation to the attributes and needs of contemporary societies, aiming towards the integrated development through the museum and with society’s participation in the definition, management and socialization of local cultural and natural goods;

-

The sociologic theory of activist nature known as Ecology of Knowledges, a line of thought that answers the challenges of an alternative globalization, having as a starting point: a) the conception of a post-abyssal thought (inspired by “learning with the south”; b) the co-presence of agents and the possibility of building a global social justice, from a global cognitive justice that recognizes the existence of a plurality of ways of knowledge beyond the scientific; c) the idea of inter-knowledge (Santos 2009);

-

The line of valorization of Cultural Diversity as created by UNESCO and, above all, its impact on recognizing the intangible dimension of our cultures which results in disrupting the hierarchic vision of Heritage, in the definition of collective, dynamic, and polysemic notions of the concept, and in the inclusion of local cultural knowledge, creativities and expressions in the developmental process (unesco 1989, 2001, 2003 and 2005).

12

13To this theoretical base one should add a set of convictions that not only motivated the creation of the project, but also led us to different discoveries and to the creation of products with a unique anatomy over the last four years (Sancho Querol 2016). Among these convictions are:

-

The need to take a step further in the path of overcoming the hegemonic management models that have been predominant until today in most museums, disseminating ways of operation that transform horizontality, decentralization, citizen empowerment and cultural democracy in an expanding museological ethic.

-

The certainty that the verb to participate (or the noun “participation”) is in every (museum) place and (nearly) nowhere, having become a crutch term in policies, speeches or museum projects, despite that in practice it is seldom connected with the exercise of a museum democratization committed to society’s cultural development.

-

The objective of focusing attention in projects that work on the basis of what Sherry Arnstein (1969) and Juan Bordenave (1983) call “citizen power”, to analyze them, systematize their practices and disseminate its management models, as more and more museums are searching for useful tools to improve its participative natures and intensities or, in other words, its societal ties. Because of this, we opted to delimit the territory of study by defining a set of selection criteria that would allow us to develop our work in local museums of small and medium dimensions, with a strong relationship with its population and territory, but also directly or indirectly linked with the sociomuseological practices[4].

-

The will to define Cultural Participation as an essential museum function with its own codes, metrics and values, thus strengthening the paradigm of direct participation in each daily activity of the museum.

14

15From here, and taking into account that none of SoMus museums had conducted a complete exercise of systemization of its participatory practices in order to define its working model with the society, we opted to introduce this objective as the research was taking form, with the aim to create and disseminate each partner’s own model of participatory management.

16

17Consequently, at the end of 2016 we had set the working models of the Portuguese (Sancho Querol & Sancho 2015) and the Finish partners (Sancho Querol, Kallio & Heinonen 2017). They bring to light two completely different formulas of making a museum with the society – or to build the society in the museum – with a common bridge: regular, growing, diverse and conscious participation of society in the building of (its) museum life.

18

19Our first concept of Cultural Participation emerged as a result of this first stage of research and the reflections made by each team during the process. In fact, when the project was created in 2013 we realized that the great challenge would be to replace the idea of “social participation”[5] by `cultural participation´, placing the concept on the basis of every museum actions, and culture in the center of the current development processes (Dessein et al. 2015) through the museum-tool.

20

21Thus, inspired by the work of Arnstein (1969), Bordenave (1983) or Carpentier (2013), among others, and based on the experiences and results obtained until now in the SoMus museums, we chose to define Cultural Participation as “a set of sociocultural dynamics of co-creative nature, that combines processes of micro and macro-participation with the museum as facilitator, with the aim to promote power equity between agents in the processes of decision-action, respecting the particularities of the territory and the values, needs and aspirations of the local society”.

22

2. The Objectives

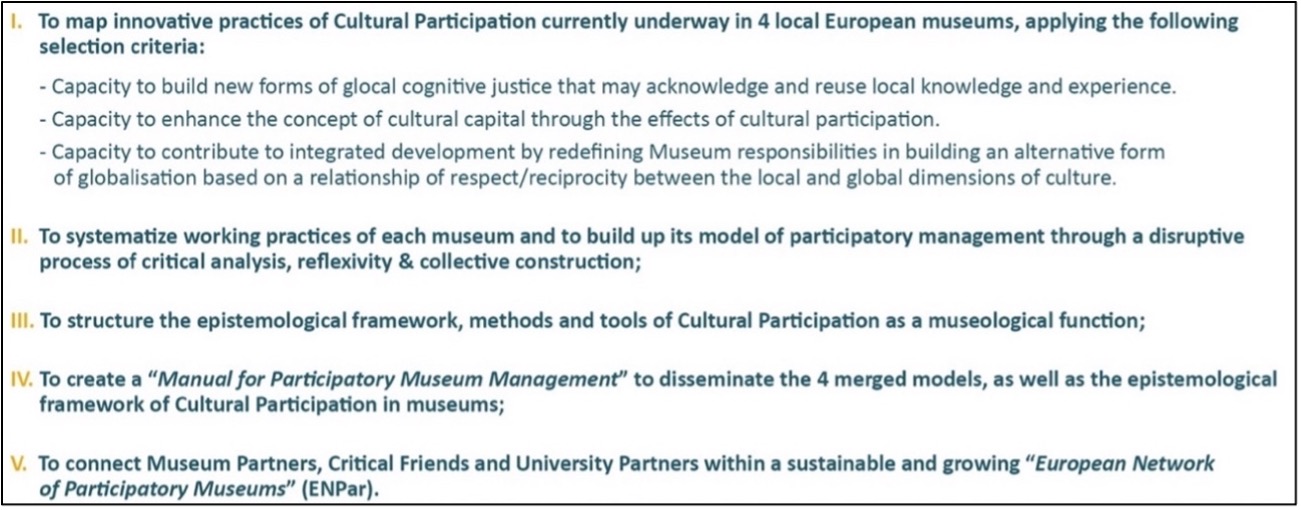

23From this corpus, SoMus structures its action-research process around the five objectives presented in TABLE 1. Departing from the deeper knowledge of the participatory practices that characterize the day-to-day of each of the museums, we aim to define a set of useful concepts and tools, as well as a network of specialists and institutions interested in sharing best practices of cultural participation and participatory management in museums, whose first members constitute those who currently integrate the SoMus Network.

24

Table 1 – SoMus objectives, 2017. Design: André Queda.

3. The SoMus team

25The architecture of the SoMus Network is formed by five segments organically articulated[6] and potentially equitative (Martinho 2001), generated from Segment 0 (S0). This segment is constituted by a researcher in the area of Sociomuseology, who leads the creation of the basic structure of the project along with the institutional partners and who assumes the role of facilitator of the processes of analysis, diagnosis, reflection and collective systematization in each museum, and promotes the communication between the network’s partners.

26

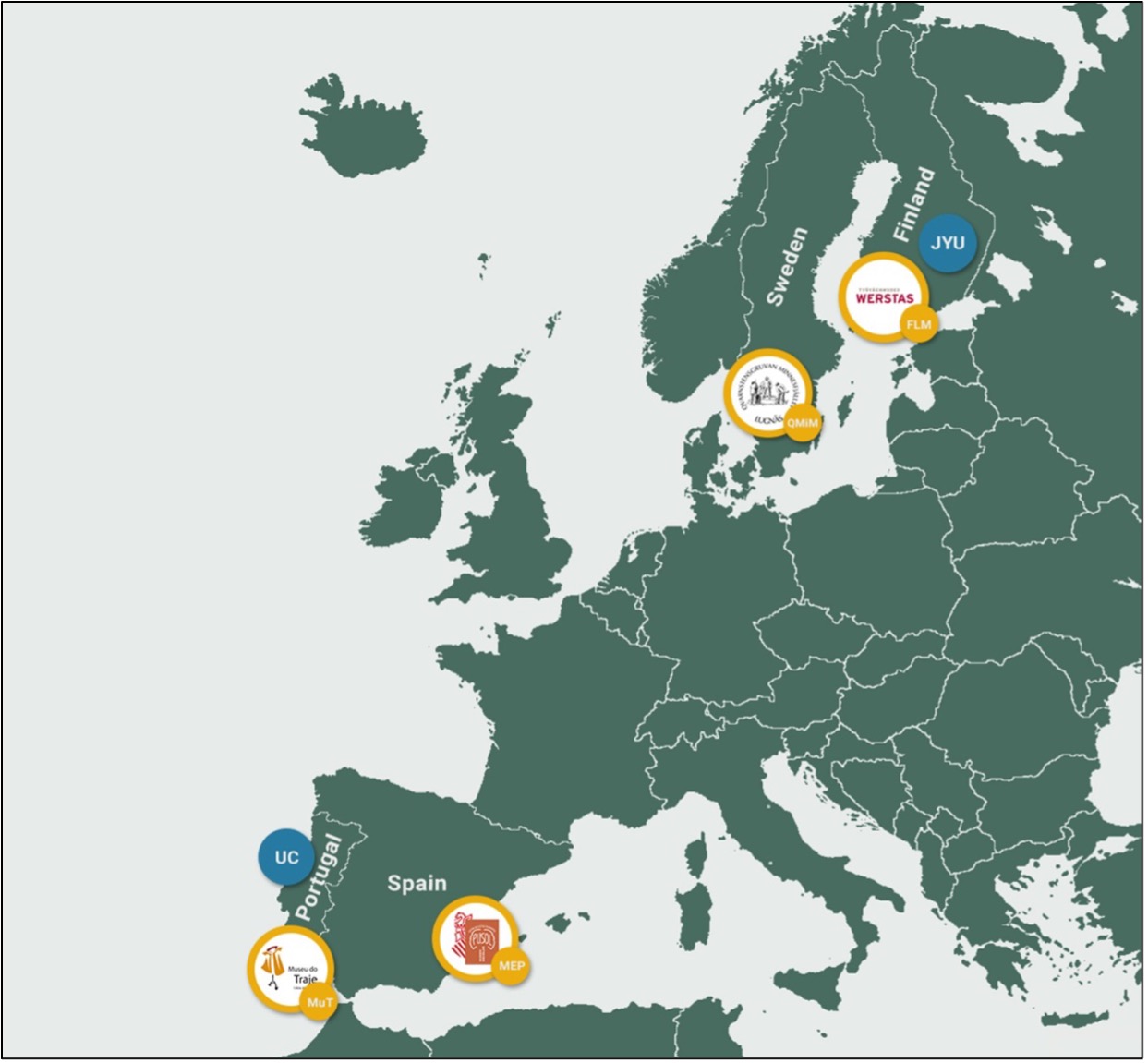

27From the S0 emerges the first level of the network, which includes the segments formed by the institutional partners of the project (fig. 1) as follows:

28

29S1. Two European universities that reflect Nordic and Mediterranean museologies, represented by professionals in the area of study and supportive of the need to work on the project’s objectives:

-

The one hosting and supervising the research process in Portugal: University of Coimbra through its Center for Social Studies (CES-UC).

-

The one sharing the supervision in a Nordic country: University of Jyväskylä, through its Department for Art and Culture (JYU).

30

31S2. Four museums located respectively in Portugal, Spain, Sweden and Finland, representing equally both types of Museology.

32

33At a second level, one can find the remaining segments, formed by those people that, being specialists, members of the public, users or simple inhabitants, help building the action-research process through their experience and knowledge, fading out the once clear borders between Museum and Society with their way of understanding and building the sociomuseological relationship. We can thus find the following segments:

34

35S3. Formed by a group of Critical Friends of different backgrounds (geographical and educational) that integrate the SoMus Network by sharing their experiences, ideas, points of view and suggestions, giving food for thought along the way.

36

37S4. Formed by the public, users (Victor 2005), researchers and populations directly linked to each museum.

38

39S5. A small team of specialized collaborators that have been helping SoMus in the making of specific tasks related to design, edition or translation, based on an exchange system tailor-made for the project.

40

41Finally, at a third level of the network one can find the SoMus´ Echoes, that is the segment made of the projects that arise from our experience (S6) that, by the hand of young researchers, are developing other dimensions of participatory museology complementary to the ones we work at SoMus.

42

Figure 1 – SoMus Museums and University partners in the map, 2017. Design: André Queda.

3.1. Museums and the challenges of a societal anatomy

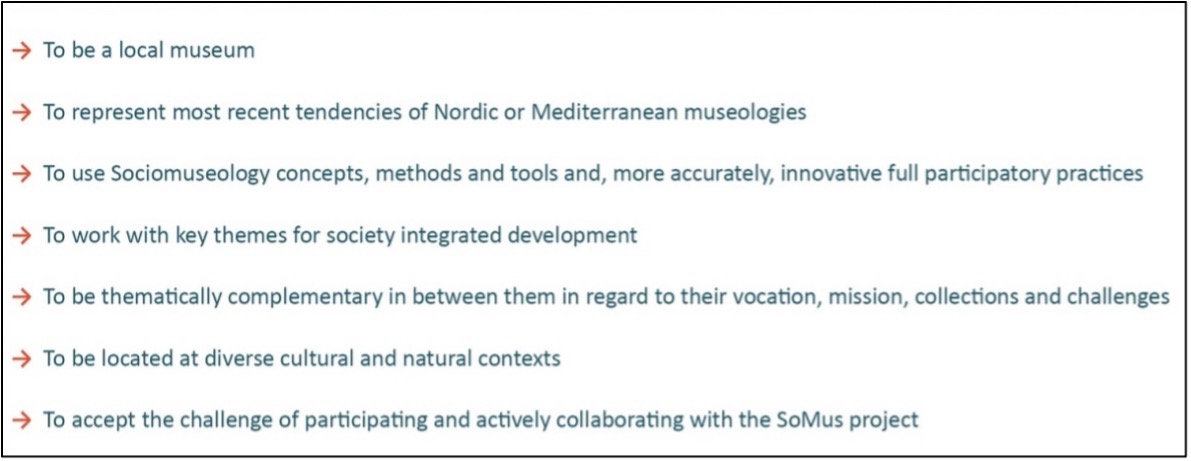

43The museums that shape the SoMus Network were selected according to a set of criteria that we present in TABLE 2. The objective was to form a representative sample of the most relevant museological lines of thought and the most innovative participatory practices in the European context. This museological structure allows the sustainability of the project from a practical point of view, taking into account its post-doctoral character and the type of support that allow its achievement.

44

Table 2 – Selection criteria of SoMus museums, 2017. Design: André Queda.

45Beyond this, each museum’s most innovative project in course was selected, taking into account not only its participatory nature and intensity but also the local impacts, with the aim of analyzing it thoroughly. This project defines the thematic represented by the museum in the context of the SoMus Network, where each partner brings a set of challenges connected with an essential theme for the cultural development of our societies.

46

47As a consequence, in order to disseminate the management model created in each museum, one collaborative article is published in a scientific journal, presenting the museum´s history and project, and describing the logics, methods and tools characterizing the daily work.

48In table 3, we present a brief technical sheet of each of the museums that complements this information[7].

49

50In this context and after a first stage of study that took place between 2014 and 2015, we were able to identify a set of museum practices that are common to the four partners and that allow us to better understand what we consider to be a shared sociomuseologic anatomy.

51

Table 3 – SoMus Museums: profiles, challenges and initiatives under study, 2016. Design: André Queda.

52In fact, SoMus museums have a strong local impact that is particularly evident at the level of integrated development, non-formal educational processes or cultural empowerment of the population (fig. 2 and 3) which is a consequence of the following measures:

53

-

A practice of an inclusive and horizontal management based on the daily interaction between professionals and local inhabitants (from equal to equal), that is, on the shared construction of projects and initiatives;

-

Development of an internal network that becomes vital for the daily achievement of the project and where organizations, collaborators, collectives and users enjoy an autonomy based on free initiative and the co-accountability of the museum.

-

Creation of unique sustainability formulas based on ecological values, social justice and appreciation of culture on its global dimension;

-

Setting up new rhythms and museum forms in harmony with the objectives, desires and needs of those sharing with them the territory, the history and the present.

54

Figure 2 – SoMus Museums, 2016. Design: André Queda.

Figure 3 – Daily life at the SoMus Museums, 2016. Design: André Queda.

4. The Method

55From the Greek meta hodos, the word method means “way to follow”. The way to know each of the museums, its projects and practices in depth, as well as to rethink the present management models and bring new contributions for this field, was that of the Participatory Action-Research (PAR). PAR is a methodological and ideological alternative that is based on full participation practices[8] and on networking characterized by its transforming and decolonized features (Gabarron & Landa 2006). In the case of SoMus, it implies a set of actions done by hand in hand by people of the academia, museums and of the societies in connection.

56

57In this type of context, and using PAR methodologies, we also proposed:

-

To think the museum in an organic and evolutive relationship with society, putting at stake the unicity of the managements models that have been used in Museology;

-

To contribute to the overcoming of the dichotomies subject-object and society-museum and, at the same time, to the emergence of a full participatory Museology;

-

To bring to the academia the shared production of new tools in equal parts by the museum and the society, acknowledging the importance of both as partners in the process of research and transformation and as protagonists of the RRI process.

58

59It would become necessary to build the path adapted to each museum’s team and to the challenges and objectives that would show more useful for each case and for each step along the path.

60

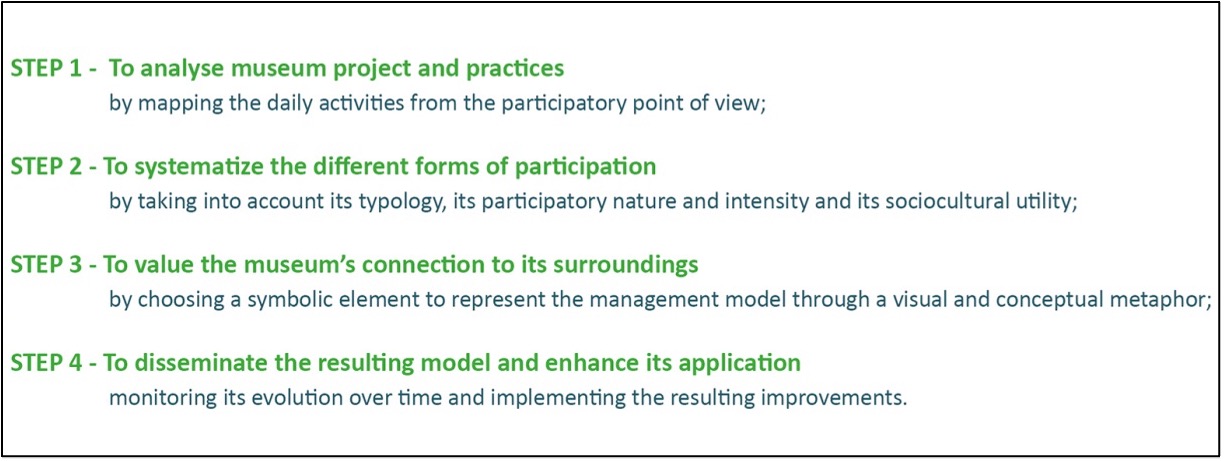

61Under this perspective, and after knowing the backstages of each museum and identifying the potentials of their work experience, we started to realize that the best way to achieve the desired results would be to put into practice the four steps that are presented in table 4. They result from the PAR process, are based on the principles of community-based research[9] developed in RRI and are somewhat similar to the model used in the “Workshops for the Self-diagnosis and Proposal Writing”[10] (Talleres de Autodiagnostico y Elaboración de Propuestas) in Mexico (Hurtado 2006). Nonetheless, what makes us different is the nature of the projects, the diversity of worlds involved in each museum and the slow pace of the way forward caused by the fact that we are dealing with four different partners. At the same time, we are also inverting the normal order of the processes used in Museology by departing from the practice to build new working tools so as to theorize on museum management.

62These four steps consist of:

63

64STEP 1: Get to know in depth the project and the participatory practices through the use of:

-

Documental research (about local history and of the museum’s, national museum policies, the project under study….)

-

Semi-structured interviews done to four different groups: the museum’s team (in these museums the interviews included all the groups above mentioned: permanent team, collaborators, users…), project team selected in each museum (also including different types of agents), visiting public and local inhabitants[11].

-

Participatory observation in the museum’s area and surroundings;

-

Research and collective reflection tools such as Self-Diagnosis Workshops, Roundtable Discussions (in each and in between museums) or Cultural Maps.

65

66STEP 2: Systematize the collected information through cross-linking the data with each team, organizing activities according to three different criteria that emerged over the course of the work: typology and objectives, participatory nature and intensity, sociocultural value. From here the various worlds that bring life to each management model and that allow the understanding of each partner’s museum mechanism were defined.

67

68STEP 3: Represent in a symbolic and in-context form the management models, linking them to the place of origin, by:

-

Choosing a symbolic element of local culture for the people and for the museum, but also for the understanding of the context where the models emerges from, creating a visual metaphor that allows us to represent each of the systematized models with its own semantic;

-

Defining a common chromatic code to the four models, allowing the representation of the various elements according to its museum nature and value. With this objective we used blue for the organizational questions and museum functions[12], green for the actions symbolizing society participation in the everyday life of the museum, orange for working tools defining a museum participatory ethic in the long term (projects, strategies, manuals…) and red for the various effects and impacts of the sociomuseological co-production process.

69

70STEP 4: Disseminate the created models while monitoring their evolution in time, identifying the resulting improvements and incorporating them in the respective models.

71

Table 4 – SoMus Steps for the definition of a Participatory Management Model, 2017. Design: André Queda.

5. Management models created until now

72Following this methodology, by the end of 2016 we had implemented the first three steps with the partners with whom we developed the work between 2014-2016 with: Portugal and Finland. As a consequence, two different models emerged: one the “Management Model of Museum in Layers”, in the case of the Portuguese partner, and another model with a completely different approach that brings us closer to the Nordic experiences in applying corporative management to the cultural sector: the “OPTI Participatory Management Model”. In both cases we are currently following closely the actual application of the model and its evolution in time, so as to monitor its usefulness and apply necessary refinements. Thus, we hereby present the last version of each model[13].

73

74In the meantime, along 2017 we could conclude stages 1 and 2 in with our Spanish partner, and in 2019 we could disseminate the results[14].

75

5.1. The management model of the Portuguese partner

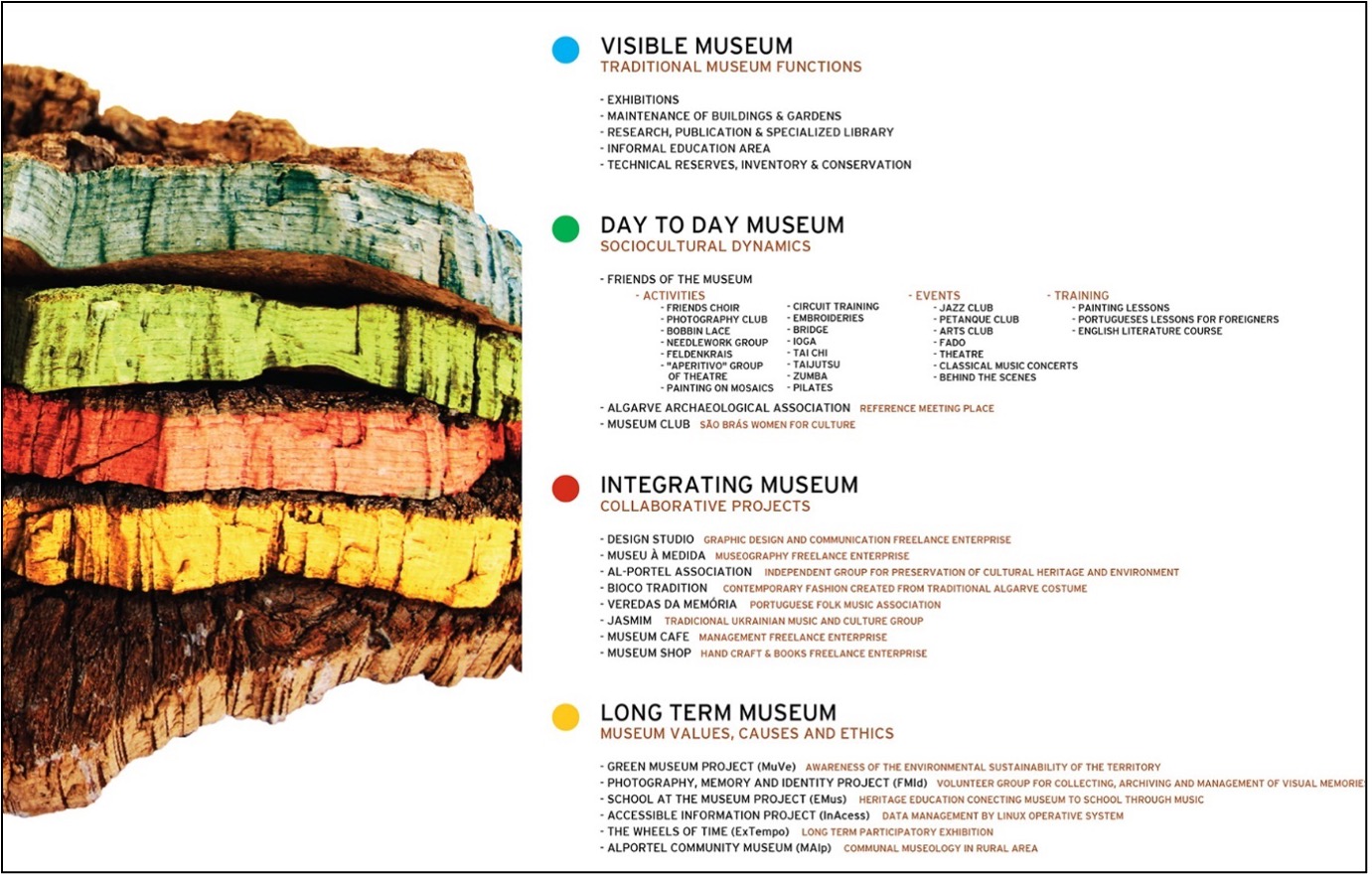

76The Costume Museum of São Brás de Alportel (MuT)[15] is located in the interior of the Algarve, in a rural context that grew around the cork industry (fig. 4).

77A founding and dedicated member of the Algarve’s Museum Network (RMA)[16], MuT has the mission to “Preserve and link local and regional identities, promoting crossings and representing a place of integration and development of its community”. It is, therefore, a museum whose strength comes from networking (Castells 2011) that is the center of its creation and that has been carried over in close relationship with local society since its origins in 1983.

78

Figure 4 – Piece of Cork with 6 years (approximately 54 years), 2014. Photo: MuT.

79This museum has a permanent team of three people to which adds on collectives, associations, collaborators, volunteers and users to develop a set of activities that are deeply inspired by the principles of Sociomuseology.

80

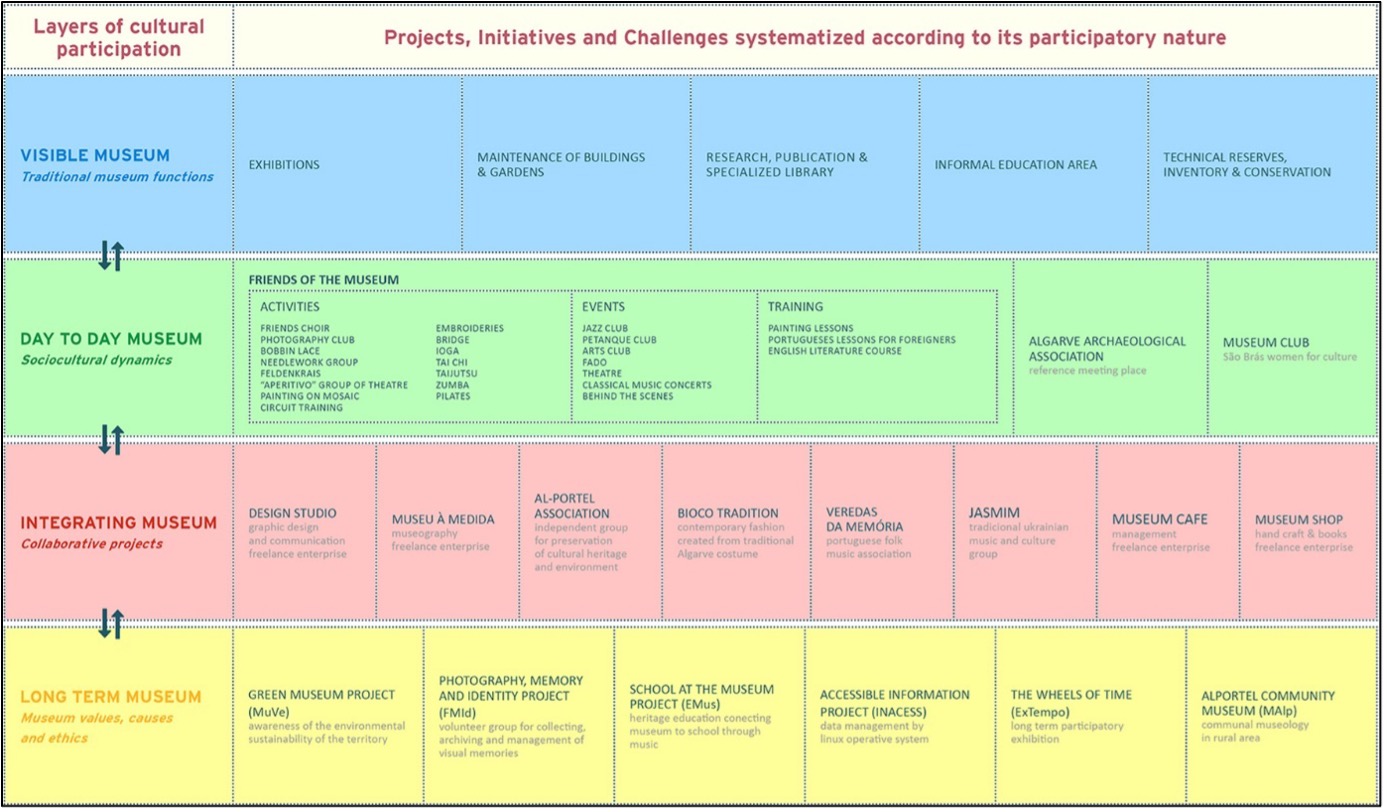

81In this case, the application of the SoMus methodology together with a diverse and committed team with its own dynamics resulted in the emergence of four different layers of cultural participation closely interconnected. Beyond shaping the museum project in network with society, these layers allowed to define the name of the management model (table 5).

82

83In this model, the layer of the Visible Museum (blue) takes as its starting point the museum practices which are currently recognized globally as related to exhibitions and catalogues, research and publication, collections and heritage educational activities. This layer is especially directed towards the visiting public who are looking for more information on local culture, thus exchanging points of view with other realities.

84

85In this “visible museum” inhabits a second layer of participation that brings to life the Day to Day Museum (green). It is in this layer that the “Friends of the Museum”, thanks to the autonomy provided by the management, as well as its meaningful relationship with local inhabitants, is able to provide training, socialization and a diverse set of cultural activities. The building of the Day to Day Museum demands the presence, attention and constant listening of the needs and aspirations of those sharing the MuT’s territory. It requires living with people, identifying synergies that allow to follow the rhythms and to take advantage of the local knowledge, time and spaces, turning the Museum useful to society. This process has been resulting in a growing affluence of public and users, through a diversified daily use of spaces and, consequently, has been generating increasing revenue that results in a stable functioning of the Friends organization. In the same layer, one can also find other initiatives of local cultural creativity that come into life at the museum.

86

Table 5 – Participatory Management Model of “Museum in Layers”. (Step 2: Systematization). Costume Museum of São Bras de Alportel, Alarve, Portugal.

87At a deeper level where less visibility combines with a growing local value, another layer emerges. It integrates within its spaces long term projects, services, new businesses, ideas, dreams and local associations taking on the role of an Integrating Museum (red). Within this framework, MuT performs yet another social function: that of supporting people and organizations in pursuing its individual and collective objectives, building through proximity and complicity a collaborative community of interests, which complement and intersect each other on a daily basis. This interaction also allows for the consolidation of a sociocultural facet of the museological project through new collaborations, diversity of experiences, cultures and skills, the creation of innovative services, in short, the social renovation based on local cultural development.

88

89At last we find the base layer, that is, the least visible layer but nonetheless the most structural in the construction of a long term sociomuseological balance of MuT. Such is due to both its ethical implications and its capacity to make the museological project sustainable, but also to the way it contributes to the recognition of the role of the Museum within the scope of local development. We are referring to the Long Term Museum (orange), a layer of MuT where we find the initiatives and projects which, in the long term, define the essence of the museum.

90As in a cork tree, these layers of museum action coexist in deep interconnection in space and in the day-to-day timing of MuT. Therefore, to take the third step of our methodology, we chose to establish a conceptual and visual metaphor between the cork´s culture and the MuT’s management model[17].

91

92The participatory management model of MuT is represented in table 6:

93

Table 6 – Participatory Management Model of “Museum in Layers”. (After Step 3: Valuing the surroundings). Costume Museum of São Bras de Alportel, Algarve, Portugal.

94This, as well as the following, are living models with unique rhythms and paths and, consequently, in constant evolution. In the case of the MuT each of its layers brings its cultural dynamics, its daily challenges, its ups and downs, its vital connections with the other layers, its ideological relations with the museum’s project that integrates them. Here, the “whole” is made of the creative and transformative strength of each of the parts and vice-versa, each part needing the others to materialize, being itself an essential link of the museum’s whole.

95

5.2. The management model of the Finnish partner

96Finnish Labour Museum (FLM)[18] is located at the old industrial area of Tampere, Finland’s largest industrial town since the early years of the XIX century and practically until the end of the XX century, mostly due to the rapids of River Tammerkosky (Kallio 2010).

97Consequently, industries such as metals, textiles or footwear experienced several golden eras throughout the nearly two centuries of Tampere’s existence. Of these memories, only a cardboard factory at the service of the tobacco industry is left, as well as a museum placed at the old textile factory Finlayson, the Työväenmuseo Werstas or Finish Labour Museum (FLM).

98

99Member of the Finnish Museum Association (FMA)[19], the FLM was created in 1993 when the industrial development period finished as the result of the emergence of new outside producers that took over the production of the referred industries.

100

101Guided by the objectives of contributing towards the knowledge of the labour and social history of Finland, deepening the concept of labour heritage – its values, uses and social appropriations – and bringing life to a model characterized by shared management and critical pedagogy, FLM has been following a Museology that is strongly committed to the cultural development of present societies.

102

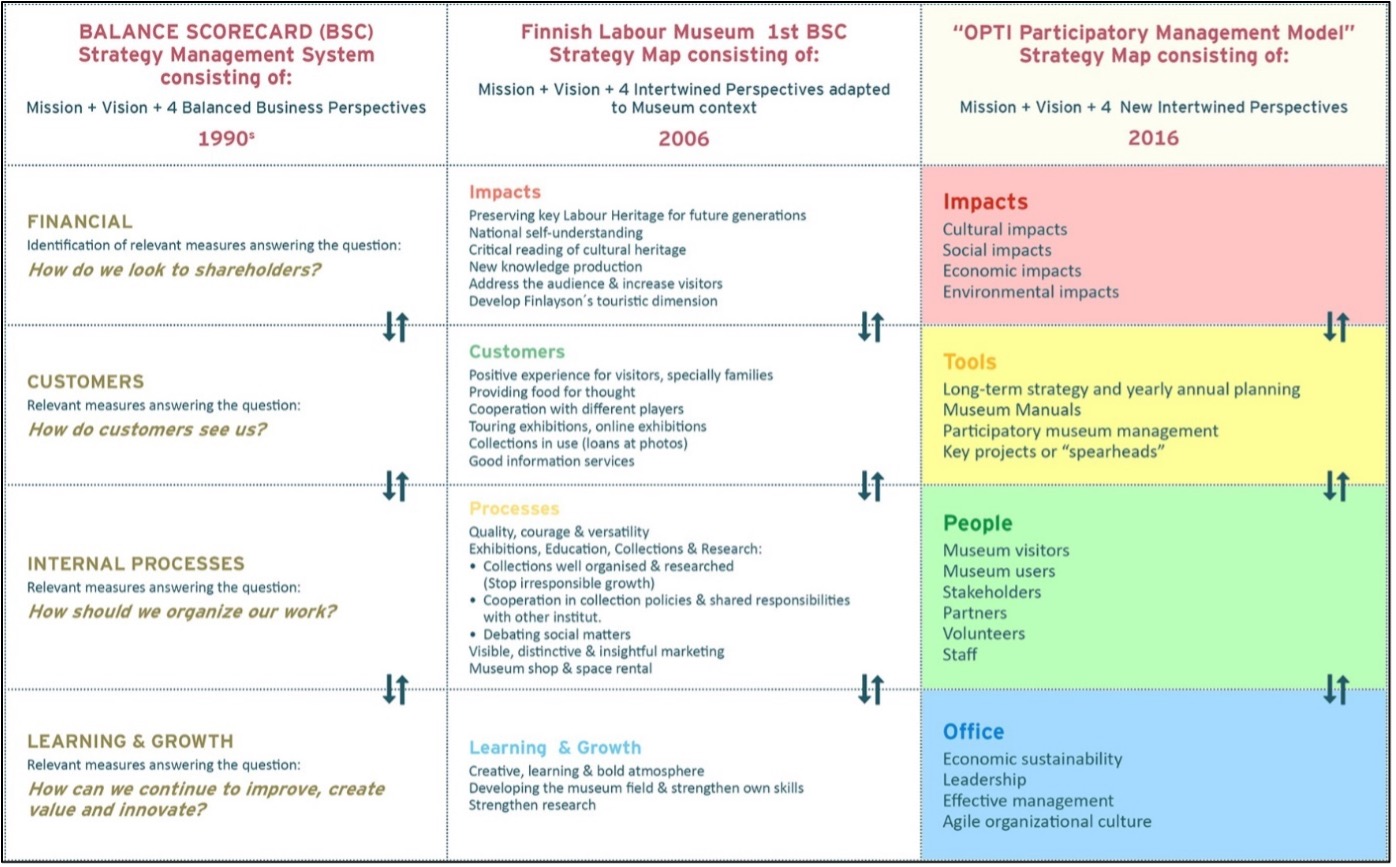

103In this context and considering that its most recent management model was created in 2006 based on the Balance Scorecard[20] system, or BSC (Kaplan & Norton 1996), we chose to start our work by analyzing this interesting experience and consequent results.

104

105We thus studied the adaptation of the four perspectives of BSC (Financial, Customer, Internal Business Processes, Learning and Growth) to the uses and challenges of a museum project as open and evolving as the FLM, in order to understand the advantages and disadvantages of BSC when applied to a museum context. As a consequence, we discovered that the most relevant measures consisted of:

-

Defining the FLM’s Mission in harmony with the building of a better society by taking the challenge of bringing to life a “Fair History”, whether looking into the past or into the chapters that we witness and of which our generation is part of;

-

Adapting the four perspectives of BSC to the characteristics and needs of the FLM, giving rise to the new strategic map of the museum formed by four areas where:

-

Cultural Impact replaces the Financial Perspective, taking into account that Labour Heritage becomes the central target of the project;

-

Customers and Internal Business Processes are dealt with under a broad and inclusive perspective of the concepts and practices of the museum;

-

Learning and Growth focuses on an internal management that is sustainable, creative and bold, and also deeply inspired by the sharing of power;

-

-

Improving the a) planning and management of processes, resources and short, medium and long-term objectives; b) assessment of on-going initiatives; c) identification and correction of detected management failures.

106

107Considering the relevance of the results obtained in this experience, the 10 years after the first adaptation and the challenges posed by SoMus, we opted to review this first step of the BSC and to rethink this strategic tool from the point of view of cultural participation. As we had concluded through our study that it still is a very useful tool for the museum’s management, the challenge consisted of doing an in-depth analysis of the democratic character of the project and possible improvements, but also in updating the management model implemented in 2006. With this objective in mind, along 2015 we analyzed the concepts, logics and practices in use and reorganized and updated them taking into account the evolution of the FLM project, bearing in mind the above mentioned SoMus methodology (Sancho Querol, Kallio & Heinonen 2017).

108

109Under the name “OPTI Participatory Management Model”, the new map of strategic management is integrated by four areas that start from the mission of the museum. These areas co-exist in deep interconnection according to a logic of a meta-combination that gives preference to the human dimension on the daily management.

110

111According to the new logic, OPTI is based on the institutional dimension of the project: Office (blue). From such dimension and by applying the sociomuseological principles, the museum develops its day-to-day with People (green), so they become essential in the daily management of the museum (that is, they are not mere customers any more, as in BSC or in 2006’s adaptation, when the museum began to reshape this border). From here, useful Tools (orange) for the evolution of the project and its protagonists are defined. Finally, as a result of this living structure we can obtain the desired Impacts (red). Under this perspective and considering the language used throughout the research process, by joining the initials of the four dimensions we obtained the acronym of the new model[21]: Office, People, Tools, Impacts.

112

113In table 7, we present the adaptation process of BSC to the FLM’s museum’s context until reaching the last results obtained with the SoMus project in 2016[22].

114

Table 7 – From Balance Scorecard to “OPTI Participatory Management Model”. (Step 2: Systematization). Finish Labour Museum, Tampere, Finland.

115Finally, during the third step of the SoMus’s methodology, we decided to use an object-metaphor that could symbolize the connection between the museum and the territory, thus we chose the steam engine flywheel that powered the textile factory during XX century and that currently integrates the FLM (fig 5).

116

Figure 5 – Steam Engine of the old FINALYSON Factory, 2014. Photo: FLM.

117On table 8, we present the result of this symbiosis where the strategic map of the new management model merges with the wheel that once fed the steam engine of the old Finlayson factory.

118

119We hope that this symbiosis of shapes and strengths allows the optimization of the contemporary uses of one of the objects that better symbolizes the productive capacity of Finnish society and of its Labour Museum in the 21st century.

120

Table 8 – OPTI Participatory Management Model. (After Step 3: Valuing the surroundings). Finish Labour Museum, Tampere, Finland.

Final thoughts

121Between 2014 and 2017 we began to realize that the evaluation of a museum project through the perspective of its participatory quality – and its impacts on society – allows us to X-Ray the museum’s anatomy, mapping each of the muscles and analyzing the ways they articulate themselves, interact and relate to the world.

122

123It was not by chance that several museums rejected our challenge during the process of selecting partners for the creation of the SoMus structure, when they realized that we would X-Ray their participatory practices and this would show the fragilities of the museum project from the participatory point of view.

124

125It was not by chance that by applying the “Management Model of the Museum in Layers” (MuT) to other local museums in Portugal, different situations were discovered allowing us to realize, for example, that the Long Term Museum´s layer lacked consistency and own strength. Such is due to the fact that the projects did not have a current mission and their own ethical values defined in line with the sociocultural challenges that our societies are currently living.

126

127It was not by chance that during the 10 years of work since the first adaptation of the BSC, the FLM team realized that in order to reverse the traditional museology logic, it was necessary to focus on the human side of the project – not objects, as it is typical of the latter, or processes, as it is characteristic of the BSC: they are both useful tools that allow materializing the objectives and needs of the people who bring the project to life. At the same time, the FLM has broadened its concept of customer by integrating society in its various forms in the regular tasks of the museum, thus developing its sociomuseological dynamic. Since then, this museum has been working in an open and flexible network system with society, giving shape to a project that is culturally useful, productive and transformative.

128

129In fact, we chose these partners not only because we wanted to work on the small scale and in the context of a local Museology connected to society, but also because among the museums that met our criteria they were the first to accept SoMus challenges and to understand the value of a participatory research committed to create new formulas of cultural democratization through museums. They were also the first to realize that the exercise we were proposing would bring reflexivity, would help to develop critical spirit and improve working methods, would reinforce the emancipatory character of the daily processes and the museum-society relation.

130

131Faced with the need to overcome the formulas that we see exhausting around us, we dared to dive into other contexts to draw up an inventory of forms of cultural participation that could decolonize the museum, to reverse the dominant paradigms, to give voice to those who had not yet (been recognized) the ability to make museum.

132

133Two different working models have been created and their existential logics allow us to think over the key issues of a shared management. One comes from Nordic Europe and brings with its business precision, methodological systematization, regular assessment, open network organizational culture and critical pedagogy. The other comes from Mediterranean Europe and brings with its new forms of multicultural cohesion, dynamics that emerge from the progressive empowerment of local society, and also the exercise of unique and evolutionary rhythms defined by local needs and desires.

134

135Both accepted the challenge of a plural and integrated leadership where each decision results from a multiple consensus negotiated between diverse worlds, thus contradicting the dichotomous management based on the museum-society and object-subject division.

136

137Both have their own ethics and a long-term strategy of which the mission that moves them is at the base, as well as the need to be selfsustainable. They remain vigilant to change, to ongoing cultural processes, to the untold and the unseen.

138

139Both are learning to weave their societal networks into a shared and everyday interweaving of threads of different natures, intensities, meanings and values.

140

141Both practice a pedagogy of otherness, nurture micronarrative and collect a more culturally equitable present.

142

143Both have four members in its corpus of management, a corpus that matures through daily exercise, self-knowledge, looking outside and within at the same time… a corpus that inspires in plural and expires experience.

144

145In fact, we wanted to work with museums that have their own participatory dynamism because they exercise it in its most diverse forms. For this reason, we escaped what we call a sedentary museology; a museology that tends to be culturally static, that uses hegemonic discourses and that is less interested on the in between spaces, narratives, memories or presents, i.e. those that make the difference in understanding our current society.

146

147To be a SoMus museum means to have an open-door policy to the present, to accept the challenge of growing each day along with people, their longings, dreams, needs, frustrations and conflicts. It also means questioning museum practice from a democratic perspective, moving beyond static models where there is only a single truth, a unique history or a predefined narrative.

148

149The path is neither easy nor straightforward, but it can contribute to the reformulation of current management models – condemned in large part by the erosion of State support – while providing them with greater management autonomy, an increasingly essential need for sustainability and the possibility of helping museums to be useful tools of cultural democracy building, hand-in-hand with society.

Notes

150[1] This article is a scientific product of the postdoctoral project “Society in the Museum: A Study on Cultural Participation in European Local Museums” (SoMus). SoMus is co-financed by the European Social Fund through the Human Potential Operational Program, and by the National Portuguese Funds through Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT), Portugal, within the SFRH / BPD /95214/2013 post-doctoral fellowship. More information on the SoMus page at: http://www.ces.uc.pt/projectos/somus/.

151[2] “Responsible Research and Innovation” (RRI) is the name used by the European Commission in its programs on “Science and Society” to refer to the innovative research that engages society in an inclusive and sustainable manner, which translates in a larger and more adequate set of positive impacts for each project. More information on RRI in: https://www.rri-tools.eu/.

152[3] SoMus museum´s selection criteria are available at: https://www.ces.uc.pt/projectos/somus/index.php?id=12417&id_lingua=1&pag=12433.

153[4] Three of the selected museums develop their practice according to Sociomuseology logics, values and principles, although not being aware of this current in theoretical terms. We thus opted to mention them as Indirect Sociomuseology projects.

154[5] Developed by several authors, we highlight the definition of Juan Bordenave, for whom social participation is “the process through which all social layers take part in the management and enjoyment of goods in a historically determined society” 1983, p. 25.

155[6] More information about SoMus Network is found at the project’s web page (in construction) in: http://www.ces.uc.pt/projectos/somus/index.php?id=12429&id_lingua=1&pag=12430.

156[7] For more information on the SoMus museums, please consult the respective section of the project webpage at: http://www.ces.uc.pt/projectos/somus/index.php?id=12417&id_lingua=1&pag=12433.

157[8] These concerns to the practices that fully include society in every part of a process or project, from the definition of the structure and decision making to the implementation of the resulting measures, the assessment or evolution of the process. Carole Pateman (1992/1970) calls them “full participatory” practices – as opposed to practices of “pseudo-participation” or “partial participation” –, Juan Bordenave (1983) as practices of “active participation” – as opposed to “passive participation” – and Nico Carpentier as practices that, in reason of their participation intensity, may be classified as maximalists as opposed to the ones of minimalist intensity (Carpentier and Jenkins 2013).

158[9] Commonly known as “Community-Based Participatory Research” (CBPR), this is one of the options of work with civil society organizations in the scope of RRI. More information in: https://www.rri-tools.eu/how-to-stk-csos-co-create-community-based-participatory-research.

159[10] In Talleres de Autodiagnóstico y Elaboración de Propuestas (also known as TADEPs) the process used is formed by five steps: start from practice, systematize practice, theorize practice, deepen practice and return again to practice (Hurtado, 2006, p 203-204).

160[11] Other information on SoMus’s teams: http://www.ces.uc.pt/projectos/somus/index.php?id=12417&id_lingua=1&pag=12433.

161[12] Their definition is found on ICOM’s Code of Ethics: http://icom.museum/the-vision/code-of-ethics/.

162[13] These upgrades are most evident in the case of MuT where, in 2016, we followed closely the evolution of the model. Therefore, it is possible now to compare the draft version published in Sancho Querol and Sancho, 2015, with the current one.

163[14] Entitled “On ruralities and resistances: The new management model of Pusol School Museum (Spain) and the challenges of reciprocal participation between museum and society”, the scientific article was published in 2020 at the Museum Management and Curatorship Journal, and can be accessed at: https://doi.org/10.1080/09647775.2020.1803116.

164[15] More information on MuT in: http://www.museu-sbras.com/.

165[16] More information on RMA in: https://museusdoalgarve.wordpress.com/.

166[17] For a closer understanding of MuT’s participatory management model, we suggest the following SoMus publication: How can museums contribute to social and cultural change? (Sancho Querol & Sancho 2015).

167[18] More information on FLM in: http://www.werstas.fi/?lang=en.

168[19] More information on the Finish Museum Association (FMA) in: http://www.museoliitto.fi/en.php?k=9064.

169[20] Balance Scorecard Strategic Management System is one of the most used strategic management systems in the corporate world. To become aware of how BSC works, please see: https://hbr.org/2007/07/using-the-balanced-scorecard-as-a-strategic-management-system.

170[21] Taking into account that the work with FLM was made using the English language, the name of the model was thought of from the name of the areas in English.

171[22] We included the table that results from the OPTI application during 2016 in the article that has been published in the vol. 2 (2017) of the Nordisk Museologi Journal [author(s)].

Bibliographie

Arnstein Sherry, 1969: « A Ladder of Citizen Participation », JAIP, vol. 35, n° 4, p. 216-224.

Bordenave Juan, 1983: O que é participação?, São Paulo, Brasiliense.

Carpentier Nico & Jenkins Henry, 2013: « Theorizing participatory intensities: A conversation about participation and politics », Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, vol. 19, n° 3, p. 265-286. Available on: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1354856513482090.

Castells Manuel, 2011: « A Network Theory of Power », International Journal of Communication, n° 5, p. 773-787.

Dessein Joost, Soini Katriina, Fairclough Graham & Horlings Lummina, 2015: Culture in, for and as Sustainable Development. Conclusions from the Cost Action IS1007 Investigating Cultural Sustainability, Jyväskylä, Jyväskylä University Press and European Cooperation in Science and Technology.

Gabarron Luis R. & Landa Libertad H. 2006: « O que é a pesquisa participante? » in Brandão Carlos R. & Streck Danilo R. (coord.), Pesquisa Participante. O Saber da Partilha, São Paulo, Ideias & Letras, p. 93-121.

Kallio Kalle, 2010: « Labour Heritage and Identities in Tampere », in Rantanen Keijo (ed.), Living Industrial Past. Perspetives to industrial history in the Tampere region, Tampere, Museum Centre Vapriikki and Finnish Labour Museum, p. 110-135.

Kaplan Robert S. & Norton David P., 1996: « Using the Balance Scorecard as a Strategic Management System », Harvard Business Review, January-February 1996, p. 75-85.

Martinho Cassio, 2001: « Algumas Palavras sobre Red », in Márcio Silveira Caio & Da Costa Reis Liliane (org.), Desenvolvimento Local, Dinâmicas e Estratégias, Rede DLIS/RITS, p. 24-30.

Moutinho Mário, 2010: « Evolving Definition of Sociomuseology: Proposal for reflection », Cadernos de Sociomuseologia, n° 38, p. 27-31. Available on: http://revistas.ulusofona.pt/index.php/cadernosociomuseologia/article/view/510

Parteman Carole, 1992 (1970): Participação e teoria democrática. Rio de Janeiro, Paz e Terra.

Sancho Querol Lorena, 2013: « Para uma gramática museológica do (re)conhecimento: ideias e conceitos em torno do inventário participado », Sociologia, Revista da Faculdade de Letras da Universidade do Porto 25, p. 165-188. Available on: http://ler.letras.up.pt/site/default.aspx?qry=id04id111id2623&sum=sim

Sancho Querol Lorena, & Sancho Emanuel, 2015: « How can museums contribute to social and cultural change? », in Jensen Jacob T. & Lundgaard Ida B. (coord), Museums: Citizens and Sustainable Solutions, Danish Agency of Culture, Denmark, p. 212-231. Available on: https://www.academia.edu/9641273/How_can_museums_contribute_to_social_and_cultural_change

Sancho Querol Lorena, Kallio Kalle & Heinonen Linda, 2017: « OPTI: a new model for participatory museum management », Nordisk Museologi, n° 2, p. 105-123. Available on: https://journals.uio.no/museolog/article/view/6350

Sancho Querol Lorena, 2016: « PARTeCIPAR. Ensaio formal sobre o conceito, as práticas e os desafios da Participação Cultural em museus », Etnicex. Revista de Estudios Etnográficos, n° 8, p. 83-100. Available on: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=6331955

Santos Boaventura S. 2009: « Para além do pensamento abissal: das linhas globais a uma economia de saberes », in Santos Boaventura S. & Menezes Maria P. (org.), Epistemologias do Sul, Coimbra, Almedina-CES, p. 23-71.

UNESCO, 1989: Recommendation for the Safeguarding of Traditional Culture and Folklore.

UNESCO, 2001: Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity.

UNESCO, 2003: Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage.

UNESCO, 2005: Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions.

Victor Isabel, 2005: « Do conceito de públicos ao de cidadãos-clientes », Cadernos de Sociomuseologia, n° 23, p. 163-220. Available on: http://revistas.ulusofona.pt/index.php/cadernosociomuseologia/article/view/403