- Accueil

- Hors-série n° 1

- Communications

- The Role of Exhibition Curators in Developing Inclusive University Museums: Imagined Audiences and Modes of Engagement in the Process of Creating the New Permanent Exhibition at the University of Tartu Natural History Museum

Visualisation(s): 1930 (3 ULiège)

Téléchargement(s): 149 (0 ULiège)

The Role of Exhibition Curators in Developing Inclusive University Museums: Imagined Audiences and Modes of Engagement in the Process of Creating the New Permanent Exhibition at the University of Tartu Natural History Museum

Document(s) associé(s)

Version PDF originaleRésumé

Cette présentation étudie la façon dont les musées universitaires peuvent contribuer à l’inclusion culturelle et sociale au moyen de leurs expositions, à partir de l’exemple de l’élaboration de la nouvelle exposition permanente du Musée d’histoire naturelle de l’Université de Tartu. Après avoir présenté les publics et les modes d’interaction imaginés, nous nous pencherons sur les facteurs ayant influencé les choix stratégiques des commissaires pour s’adresser à ces publics. La recherche qualitative se fonde sur des entretiens semi-directifs avec les commissaires de l’exposition. On utilise le concept des « publics imaginés » d’Eden Litt (2012), développé à l’origine pour étudier les médias sociaux dans des contextes traditionnels et cross-media et transféré ici au contexte des expositions. La présentation présente des propositions pour surmonter les limites et exploiter les possibilités créatives propres à l’élaboration d’une exposition afin d’atteindre l’objectif d’un environnement muséal inclusif.

Abstract

The presentation contributes to understanding how university museums can develop cultural and social inclusivity through exhibition-based activities, by taking as a case study the process of making the new permanent exhibition at the University of Tartu Natural history Museum. The paper first determines which audiences and modes of engagements were envisioned by exhibition curators, and then proceeds to investigate the factors influencing the curators in choosing strategies for engaging their envisioned audiences. Our qualitative research was based on semi-structured interviews with exhibition curators. We used the concept of « imagined audiences » from Eden Litt (2012), originally developed for studying social media, and previously applied in traditional and cross-media contexts. In examining engagement modes of museums, our research thus transfers a previously used conceptual framework to the new context of exhibition-based activities. Our presentation suggests how to overcome limitations and exploit the creative opportunities inherent in the creative process of making the exhibition, so as to attain the objective of an inclusive museum environment.

Table des matières

Introduction

1As inclusive institutions, university museums are finding it increasingly important to be able to engage various audiences in enhancing their own meaningfulness, as appraised both by their universities and by their overall societies. Among the tools for engaging a broad range of museum audiences are permanent exhibitions. We use the concept of imagined audiences (Litt 2012) to explore how, in the course of their exhibition-creating process, university museums are able to construct their audiences and shape audience engagement.

2

3We examine the creation of the new permanent exhibition at the University of Tartu Natural History Museum, using interviews with the curators, as the content creators. This museum has long had public audiences, beyond the university’s own internal research and education constituencies. However, this new permanent exhibition was for the first time exclusively targeted for audiences outside the university. The main goal of the new exhibition, created over the period 2010-2016, was to raise awareness of nature and environment. Our interviews were conducted during the first months after the exhibition opening.

4

1. Theoretical framework: the exhibition’s imagined audiences and modes of engagement

5We consider as museum audiences everyone with whom the museum communicates – visitors, clients, target groups, participants, and any other museum-related groups (Lotina 2016, p. 12). Following Litt, we treat imagined audiences as conceptualizations of the people with whom the museum communicates (Litt 2012, p. 331). We have found this approach useful since, as Litt shows, the composition of imagined audiences can affect how and what a museum communicates to its actual audiences (Litt 2012, p. 333). This approach has also helped us conceptualize factors that influence curators in their work. Proceeding from Anthony Giddens’s structuration theory (Giddens 1984), Litt finds audience construction to be affected on the one hand by external (structural) factors, typically environmental and institutional, and on the other hand by internal (agential) factors, in other words by the curators’ personal qualities (Litt 2012, p. 334).

6

7The concept of imagined audiences has been previously used to analyse social media (Marwick & Boyd 2010; Litt 2012; Murumaa-Mengel 2017) and cross-media processes (Nani 2018). A few analysts prior to Litt (2012) have already considered imagined museum audiences, proceeding as we do from the perspective of content producers (O’neil 2008; Smart 2008). A recent work, independent of Litt (2012), has proceeded from the perspective of visitors themselves (Coghlan 2018). We have decided to retain Litt’s (2012) concept, with its inclusion of factors influencing the imagining process, but for our part also examining what the curators envisaged as modes of audience engagement.

8

9To map the imagined audiences, we have used the identity-related visitor motivation model developed by Falk (2011) in our final stage of analysis, as we agree that one and the same individual can present a museum with multiple identities and engagements in the course of multiple successive visits (2011, p. 145). Further, we have found Falk’s concept valuable in linking our investigation, into the imagining of audiences during the exhibition-creation process, with studies of actual audiences.

10

11Supplementing Litt, we have considered how the curators envisaged the engagement of the various audiences they were imagining. To systematise our findings, we have drawn on the Lotina-Lepik museum-specific taxonomy of engagement modes, via related groups of museum activities (Lotina 2016; Lotina & Lepik 2015). In her taxonomy, Lotina has noted that in addition to engaging audiences through the obvious modes of « Informing » and « Marketing », engagement can involve « Consulting », « Collaborating », « Connecting with participants », « Connecting with stakeholders », and « Connecting professionals » (Lotina 2016, p. 59-61).

12

13In our case study, we have posed the following research questions:

-

Who were seen by the curators as the imagined audiences of the permanent exhibition?

-

According to the curators, which factors shaped and influenced their process of audience imagining?

-

How did the curators envisage their audiences as engaged when visiting the permanent exhibition?

14

2. The method: the constructivist grounded theory

15We base our case study on semi-structured interviews with twelve exhibition curators, conducted during the first quarter of 2016. At the first stage of our analysis, we applied the techniques of Charmaz’s constructivist grounded theory. Our analysis involved the coding of processes in interrelated levels – initial, focussed, and axial (Charmaz 2014) – while considering (a) the composition and engagement modes of the audiences as imagined by the curators, and (b) factors shaping and influencing this exercise of imagining. Adopting an iterative approach, we have elaborated our results in a second stage, systematising the visitor groups through a visitors-motivations typology (Falk 2011).

16

17Our twelve interviewees had different professional backgrounds. Five curators had teaching experiences at the previous permanent exhibition, while three others had only worked with scientific collections. Of the twelve, five were trained in various fields of biology, three in various fields of geology, two in semiotics, one in history, and one in information technology. Further, some among the twelve contributed to the entire exhibition, others only to parts. To protect the privacy of this small group, we keep their quotes anonymous.

18

19Since the first author of this case study had herself participated as project manager, we adopted an appropriately modulated insider-research strategy. Although an insider-research strategy has the advantages of intimate access to the given topic and an intimate appreciation of its context, extra attention must be paid to interpersonal ethics, safeguarding anonymity (Atkins & Wallace 2012). The first author accordingly contributed by preparing the interviews and carrying out the analyses, with the actual interviewing delegated to the second author. The designing of the study, the establishing of the process, the constructing of a framework for analysis, and the writing were the joint work of all three authors.

20

3. Results and discussion

21Having presented our research questions, we continue by examining firstly the audiences imagined by the curators, secondly the factors influencing the curators in their work of imagining, and thirdly the modes of engagement which the curators envisioned.

22

3.1. Imagined audiences

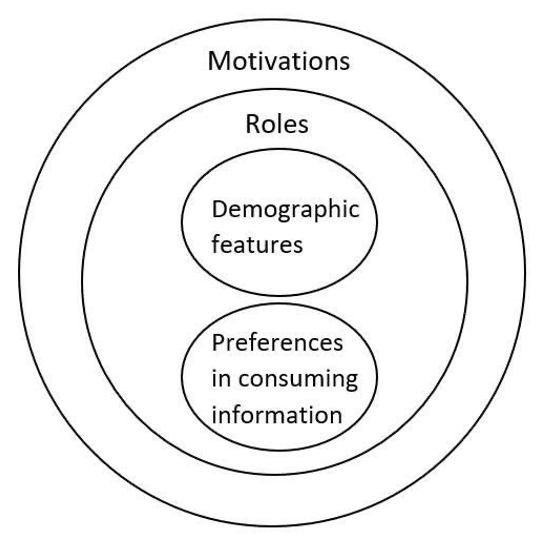

23We present the results about imagined audiences in overlapping layers, using three main categories: personal characteristics, including demographic features and preferences in consuming information; roles; and motivations for engaging with the museum (fig. 1).

24

Figure 1 – Structure of imagined audiences. The audiences present a combination of personal characteristics, including their demographic features and their preferences in consuming information (the two inner circles), their roles (the middle circle), and their framing identity-based motivations (the outer circle). Figure: authors.

25

26Among personal characteristics, demographic features such as age, geographical origin, and language preference dominated. Additionally, however, there were varying preferences for consuming information. The segmentation by demographics reflects the museum’s social inclusivity. The variation in preferred ways of consuming information (as texts, as objects, as audio, or as video) reflects its concerns for visitors with special needs.

27

28The role-based segmentation took school pupils as the principal audience, while recognizing also the potential presence of tourists, of parents with children, of specialists, and of university students. The latter appear in our segmentation with the qualification that the exhibition was not meant for them, even if they may happen to find some parts of it useful. University museums have traditionally been expected to address students. Since at present, however, permanent exhibitions of natural history have lost their role in university education, this exhibition was directed in the first instance to the public outside the university. As with university students, so also subject specialists were not emphasized. Nevertheless, the curators kept in mind that if specialists, whether from the University of Tartu itself or from other (notably from non-Estonian) institutions did happen to visit, the best of the collection would have to be presented to them, in a manner duly informed by high-quality current scientific understanding.

29

30The classification of audiences according to their motivations for visiting was consistent with the identity-based taxonomy of visitors presented in FALK 2011: the « Explorers », as those interested in the content; the « Facilitators », as those (for example, teachers and parents) who enable the museum visit for others; the « Professional/Hobbyists » (in our particular case including farmers, bird watchers, and collectors of natural specimens); the « Experience Seekers » (tourists); the « Rechargers », as those seeking contemplative experience (in our particular case, people seeking the systematicity of classical natural history); the « Respectful Pilgrims », as senior colleagues honoring the institutional memory; and the « Affinity Seekers », as those coming because of personal heritage (recalling their childhood or student years). The close alignment we have been able to achieve with Falk’s visitor identity concept points, we suggest, to the explanatory potential of a nuanced, inclusive approach to the full spectrum of audiences.

31

3.2. Factors influencing the imagining of audiences

32According to Litt (2012), two kinds of factors could influence curators: externally imposed norms and circumstances, and internal factors, involving the curators’ own qualities and decisions.

33

34For this case study, the salient external factors included the project rules that determined the exhibition goals and specified its target audiences. These rules determined our demographic and role-based audience characterizations, since the externally applied rules described the target audiences in these same categories. Also salient among the external influencing factors were resources, for the most part acknowledged at the University of Tartu Museum of Natural History as constrained. The curators’ citing a troubling paucity of subject specialists reflected the museum’s goal of setting high scientific standards, regardless of the popular nature of its new permanent exhibition. The lack of exhibition space was a second stressful resource constraint, leading one curator to say, « If it had been laid down on the ground twice as big as this, it would have been much better for a visitor to be there. » These perceived resource limitations lead us to emphasize the importance, for the curators in our chosen case, of planning their new permanent exhibition with a due regard for the needs and expectations of their imagined audiences.

35

36External influencing factors further included the university’s academic values. A curator explained: « It is a so-called integral part of the university’s research in natural history and a direct reflection of education that is related to it. In principle, this does not change now; only it becomes a bit more open to society. » This choice of language illustrates the salience, in this curator’s mind, of the educating-informative aspect of the envisaged exhibition.

37

38Internal factors involved the various curators’ skills, experiences, and motivations. Each individual curator’s background proved significant, yielding in some instances an emphasis on science, in others an emphasis on cultural layers, and elsewhere again an emphasis on visual qualities, or alternatively on the active-learning environment. Some curators were disappointed with the final compromises. We acknowledge that experts representing different fields and visions are necessary if a joint exhibition is to achieve richness and diversity. At the same time, it is important that such a team be challenged to keep its work enjoyable for everyone, controversial visions about the exhibition notwithstanding: their final challenge is the delivery of a homogeneous exhibition.

39

3.3. Imagined modes of engagement

40The dominating mode of engagement was in our case « Educating », as this was the mode associated with the widest variety of activities, including educational programmes, guided tours, events, the useful spending of free time, and the acquisition of information. A curator concluded: « A permanent exhibition is a certain type of thing. There are certain so-called regular ways to use it, mostly learning and perhaps less entertainment, but probably learning and getting to know is the most comprehensive term. » Previous research by Lotina has reached this same result regarding the dominance of the « Educating » mode (in her terminology, « Informing »: Lotina, 2016). The comprehensive nature of « Educating » does, however, now lead us to recommend further research into this mode, so that in future analyses finer detail may be discerned.

41

42The engagement mode of « Attracting the audiences » was defined by how the exhibition affects its audiences through its qualities. Among the requisite qualities, the curators mentioned visually stunning and meaningful objects, amazing details, enjoyable space, the activation of emotions, multiplicity in layers of meaning, and multiplicity in presentation modalities. Here is the key mode for engaging a broad range of audiences. We would point out that for an exhibition to be engaging, the curators must succeed in imagining audience needs and expectations with sufficient concreteness.

43

44The engagement mode of « Collaborating with audiences » involved opportunities for audiences to further the museum’s mission. The given exhibition could offer only limited possibilities for collaboration. Nevertheless, the curators did envision examples when interviewed: assistance from expert visitors, so as to correct mistakes; and additionally, the linking of the museum’s digital archives to its exhibition, in support of citizen science. We would stress the desirability of exploring such collaborations, as enhancing an exhibition’s inclusiveness and engagement intensity.

45

46The engagement mode of « Serving stakeholders » involved activities offered in the interest of stakeholders, such as the delivery of programmes to schools, and again the loaning of museum premisses to other institutions. Stakeholders may have the power to serve as facilitators for actual users, and therefore they were often addressed as cooperation partners.

47

48We thus found that analyzing imagined modes of engagement enhanced our understanding of the curators’ audience-construction process.

49

Conclusions

50Our case study has investigated the process of audience construction as a phase in the creation of a new permanent exhibition. Our results include an identification of the audiences imagined by the curators and an identification of envisaged modes of engagement. Additionally, our results include an identification of factors, both external and internal, influencing this curatorial exercise in imagining and envisioning.

51

52On the basis of our results, we offer the following suggestions:

-

Multiple approaches are available for identifying permanent-exhibit audiences (proceeding, for example, from personal characteristics, and again from role characteristics, and again from motivations). Such a diversity in approaches can usefully highlight the full range of engagement opportunities.

-

The exercise of mapping imagined audiences helps identify constituencies who may be marginalized, controversial, problematic, condemned, or even (as in the case of special-needs groups) forgotten. Developing an awareness of opportunities for engaging them contributes to developing an appropriately functional permanent exhibition. Identifying audiences who are insufficiently addressed provides an opportunity for adopting specific remedial measures, such as the preparation of supplementary printed or digital materials, or again the development of supplementary exhibition-based activities.

-

Permanent exhibitions are created by curators with diverse professional backgrounds and experiences. Sometimes, as with a natural history museum, professional backgrounds can prove highly specialized. Hence, curators are likely to differ in the ways they envisage audience engagement. Diversity in the curatorial team contributes to the creation of a rich and versatile exhibition. However, to keep the assignment motivating for them, and to secure the desired comprehensiveness for the exhibition, it is important to facilitate cooperation and feedback among the team members, the diversity in their curatorial roles notwithstanding. As team members strive for cooperation, it is helpful for each of them to be aware of the imagined audiences and the envisaged modes of engagement.

53

54Since permanent exhibitions continue to be significant in a natural history museum, we conclude that an understanding of how permanent-exhibition curators imagine audiences and envision engagement modes will help a museum increase its capacity for public outreach, thereby enhancing its contribution in society.

55

56

57Acknowledgements :

58We thank colleagues at the Institute of Social Studies of the University of Tartu and at the Estonian National Museum for helpful criticism; the Natural History Museum, for support; the curators, for consenting to our use of interviews; and our language editor.

59

60

Bibliographie

Atkins Liz & Wallace Susan, 2012: « Insider Research », in ATKINS Liz (ed.), Qualitative Research in Education, London, Sage Publications, p. 47-64.

Charmaz Kathy, 2014: Constructing Grounded Theory, Los Angeles, Sage Publications.

Coghlan Rachael, 2018: « “My voice counts because I’m handsome.” Democratising the museum: the power of museum participation », International Journal of Heritage Studies, n° 24 (7), p. 795-809.

Falk John Howard, 2011: « Contextualizing Falk's Identity-Related Visitor Motivation Model », Visitor Studies, n° 14 (2), p. 141-157.

Giddens Anthony, 1984: The constitution of society: Outline of the theory of structuration, Berkeley, University of California Press.

Litt Eden, 2012: « Knock, knock. Who's there? The imagined audience », Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, n° 56 (3), p. 330-345.

Lotina Linda, 2016: Conceptualizing Engagement Modes: Understanding Museum-Audience Relationships in Latvian Museums, [Doctoral Thesis], Tartu, University of Tartu Press.

Lotina Linda & LEPIK Krista, 2015: « Exploring Engagement Repertoires in Social Media: the Museum Perspective », Journal of Ethnology and Folkloristics, n° 9 (1), p. 123-142.

Marwick Alice & Boyd Danah, 2010: « I tweet honestly, I tweet passionately: Twitter users, context collapse, and the imagined audience », New media & society, n° 13 (1), p. 114-133.

Murumaa-Mengel Maria, 2017: Managing Imagined Audiences Online: Audience Awareness as a Part of Social Media Literacies, [Doctoral Thesis], Tartu, University of Tartu Press.

Nanì Alessandro, 2018: « “I Produce for myself”: Public Service Media, Cross-media and Producers in Today's Media Eco-system », Media Studies/Mediální Studia, n° 2, p. 28-47.

O’Neill Mark, 2008: « Museums, professionalism and democracy », Cultural Trends, n° 17(4), p. 289-307.

Smart Pamela, 2008: « Crafting Aura: Art Museums, Audiences and Engagement », Visual Anthropology Review, n° 16 (2), p. 2-24.