- Home

- 1/2020 - Special Issue - Eurasian regionalism: glo...

- Strategy Amidst Ambiguity: the Belt and Road and China’s Foreign Policy Approach to Eurasia

View(s): 4733 (14 ULiège)

Download(s): 0 (0 ULiège)

Strategy Amidst Ambiguity: the Belt and Road and China’s Foreign Policy Approach to Eurasia

Abstract

This article briefly discusses two fundamental questions on China’s growing presence in Eurasia. Eurasia is understood as Russia, Belarus, Ukraine, Moldova, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Armenia, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Afghanistan, and Pakistan. (1) What is China’s approach to foreign policy in Eurasia? (2) What role does the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) play in China’s foreign policy? The BRI is a Chinese-led infrastructure mega-project. The initiative’s aim is to coordinate maritime shipping lanes (the road) with overland transit infrastructure (the belt) from Asia to Europe. The authors conduct original research to provide the following answers. First, using a system of bilateral partnerships, China takes a hierarchical approach to foreign policy in Eurasia. That is, China ranks its relations with Eurasian counties according to a series of security concerns: protection of borders, securitisation of strategic resources, and access to markets and additional resources. The BRI has widened the scope of China’s security concerns; participation in BRI-related projects can increase a country’s importance for China. Second, the BRI is a tool of strategic ambiguity in China’s foreign policy. Ambiguity over the purpose of the BRI helps to generate collective support for the project, and gives Beijing flexibility in redefining aspects the BRI’s development to address changing circumstances, such as countries’ concerns over debt sustainability of BRI-related projects.

Table of content

Introduction

1This brief article discusses China’s current approach to foreign policy in Eurasia. Foreign policy is understood as a strategy or planned course of action to achieve specific goals according to elite and national interests. Eurasia consists of countries located on the continental land mass of Europe and Asia, but which are also considered to lie on the borderlands of Europe in the West and China in the East. These countries include Russia, Belarus, Ukraine, Moldova, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Armenia, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Afghanistan, and Pakistan. Eurasia is a heuristic unit of analysis at best. Nevertheless, the region is important to study, because of its gaining importance for Chinese foreign policy.

2China’s increasing presence in Eurasia is often framed as part of the Silk Road Economic Belt (SREB). Announced in 2013, the SREB is China’s effort to interlink with Central Asia, Russia, and Europe across the landmass of Eurasia – reminiscent of the ancient Silk Road (Witte, 2013). The word choice of “economic belt” is meant to imply “a densely occupied economic corridor for trade, industry, and people” (Maçães, 2018). Indeed, the SREB is central to the land-based element of China’s wider Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The BRI is a Chinese-led infrastructure mega-project. The initiative’s aim is to coordinate maritime shipping lanes (the road) with overland transit infrastructure (the belt) from Asia to Europe.

3Within the context of the BRI, this article poses two fundamental ques-tions: (1) What is China’s approach to foreign policy in Eurasia? (2) What role does the BRI play in China’s foreign policy? The sections below, en-titled, “Partnership Diplomacy as a Hierarchy of Eurasian Relations”, and “The BRI as Strategic Ambiguity”, provide responses to these questions.

4The first section argues China takes a hierarchical approach to its rela-tions in Eurasia. This hierarchy corresponds to a system of official bilat-eral partnerships. The partnerships are a symbolic indicator of the level of bilateral relations China has with a country. These partnerships form a system of partnership diplomacy.

5Understanding partnership diplomacy matters for analysts, China-watch-ers, and researchers, because by identifying the type of partnership China Strategy Amidst Ambiguity: The Belt and Road and China’s Foreign Policy Approach to Eurasia has with a Eurasian country, certain assumptions can be made about the importance of the bilateral relationship for China. Specifically, the higher the partnership a country has, the greater importance the country has for China. Therefore, China’s approach to foreign relations in Eurasia can be understood in a hierarchy of partnerships.

6For the most part, China’s partnership approach to foreign policy rein-forces past arguments by Zhu (2010) and Heath (2012) that China val-ues those countries that do most to address its security concerns. China’s security concerns are defence of Chinese borders, securitization of key resources (such as energy, metals, and agriculture), and access to markets and resources.

7The logic goes that China devotes most attention to those relationships that best serve these concerns. Therefore, the more security concerns a country addresses, the higher the partnership it has with China. However, this article argues the BRI has widened the scope of China’s security con-cerns. Together with traditional security concerns, the BRI has become an additional determinant of a closer partnership with China. Participation in BRI-related projects can increase a country’s importance for (and in-crease its level of partnership with) China.

8The BRI has been described as “breathtakingly ambiguous” (Hillman, 2018). One newspaper described the initiative as “One Belt, One Road – and many questions” (Financial Times, 2017). Analysts and researchers have provided multiple interpretations of the BRI’s purpose (Sidaway and Woon, 2017). The authors of this paper put forward : China’s failure to clarify the BRI’s exact purpose is deliberate. Indeed, ambiguity is central to the BRI’s current stage of development.

9The second section below argues the BRI (and by definition the SREB) is a tool of strategic ambiguity. Strategic ambiguity (explained in more detail below) means Chinese officials are deliberately vague about the purpose of the BRI. By doing so, participants provide their own justifica-tions for involvement in the project. This strategy is meant to encourage collective support for kick-starting BRI, and to give China the flexibility to adjust its approach when it deems necessary. At the same time, the BRI’s strategic ambiguity is alienating certain potential participants. The lack of clarity over the BRI’s purpose creates space for negative interpretations, which prevent wider support. Recent efforts by the Chinese government to address debt issues on certain BRI-connected projects has drawn inter-national criticism. Due to the BRI’s immense international scope, China’s experience of development sustainability in Africa offers limited insight into how it will continue to develop the BRI. Strategic ambiguity is useful in these situations, because it allows Chinese officials to react to criti-cisms quickly and to adjust the BRI during its implementation. Despite debt concerns and its China’s long-term designs for the project being unclear, Eurasian countries continue to be enthusiastic about the BRI.

Partnership Diplomacy as a Hierarchy of Eurasian Relations

10Scholars have argued China’s foreign policy is developed in accordance with its security concerns (Zhu, 2010, p. 6; Heath, 2012, p. 64). Security concerns is another name for the drivers of China’s diplomacy. “The main driver is concern about externally derived threats to China’s develop-ment and threats to China’s access to overseas resources and goods upon which its economy is increasingly dependent” (Heath, 2012, p. 64). To ensure China’s development and safeguard the economy, the Peaceful Development White Papers (which outlines the party’s guidance for for-eign relations) set out a series of core national interests to be protected. Heath (2012, pp. 64-66) interprets them as the following: (a) issues of sovereignty and territory, including “state sovereignty, national security, territorial integrity, national reunification”; (b) survival of the Communist Party of China (CPC), referred to as “China’s political system established by the Constitution and overall social stability”; and (c) those resources and goods necessary for economic development, “basic safeguards for ensuring sustainable economic and social development” (PDWP, 2011).

11In this paper, the core national interests (listed above) that drive China’s foreign policy are reduced to three security concerns. Issues of sovereign-ty and territory are shortened to defence of Chinese borders. Survival of the CPC is redundant, because its survival depends on protecting China’s national interests in the first place. Therefore, protection of the CPC does not form a security concern. Protection of resources and goods necessary for economic development makes up two concerns, securitisation of key resources and access to markets and resources (Zhu, 2010, p. 6). Thus, the drivers of China’s diplomacy can be reduced to three security con-cerns: defence of Chinese borders, securitisation of key resources, and access to markets and resources. China’s approach to foreign policy in Eurasia is to build partnerships that address these security concerns.

12Indeed, the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) has a system of bilateral “partnerships” (伙伴), which it applies to practically all bilateral relations with other countries. These partnerships symbolise the level of relations China has with a country. The authors of this article have found the level of partnership is influenced by factors, which impact the security concerns noted above. Influential factors include whether a country shares borders with China, the level of bilateral military interaction, if it trades in strategic resources (petroleum, metals production, or agricul-ture), or if it has bilateral infrastructure projects with China that facilitate trade. The higher volume of factors a country has, the higher the level of partnership with China it tends to receive.

13The different levels of MFA partnerships can be used to build a hierar-chy of bilateral partners. A hierarchy of Eurasian partnerships is useful for two reasons. First, it supports the argument that China’s foreign policy is defined by its security concerns. The existence of factors that address security concerns tend to correlate with high level partnerships, and their lack with low level partnerships. Second, the hierarchy indicates which Eurasian countries China chooses to devote the most attention to. By ranking Eurasian partnerships, China’s foreign policy approach itself be-comes more visible. China’s approach to foreign policy in Eurasia, there-fore, can be identified via the official partnerships it assigns to the region.

14The following demonstrates China’s partnership system is, indeed, linked to factors that address Chinese security concerns. The hierarchy these partnerships form is somewhat predictable, but also shows how the BRI is changing which bilateral relationships matter to China. Thus, while China has not altered its approach to foreign policy in Eurasia, new goals – like facilitating the BRI – have widened the range of strategic relationships.

15The MFA assigns six different levels of relations for all foreign regimes1.

16In order of least to most important, they are:

-

Non-strategic partnerships (非战略伙伴关系)

-

Strategic partnership (战略伙伴关系)

-

Strategic cooperative partnership (战略合作伙伴关系)

-

Comprehensive strategic partnership (全面战略伙伴关系)

-

Comprehensive strategic cooperative partnership (全面战略合作伙伴关系)

-

Special partnership and non-partnership relations (非伙伴关系)

17Hierarchical structure is essential in understanding China’s partnerships (Dai, 2016, p. 103; Cheng and Wankun, 2002; Yeliseyev, 2013). The different levels imply different expectations and significance to a bilater-al relationship (Wenwei Po, 2015). Among the various types of Chinese partnership relations, “strategic partners” (战略伙伴) are “‘closer friends’ than other countries, and among the strategic partners, there is also an implicit hierarchical structure” (Feng and Huang, 2014, p. 15). “Strate-gic” means there is some aspect of relations that have a strategic impact. Strategic concerns for China are defence of its borders, or supplies of strategic resources, or access to markets or additional resources.

18At first glance, it seems this hierarchy implies China is a unitary actor in its approach to foreign policy. It is as if there are a series of foreign policy conditions and relations with China depends on whether a country has met them or not. On the contrary, although China conducts a unified foreign policy, Chinese leadership exhibits different approaches and ide-as about various dimensions of countries’ international engagement. This is precisely what the various partnerships allow China to do – to have a flexible, dynamic approach that suits both China and its partner coun-try. This highlights the difference between “strategic” and “non-strategic” partnerships. When a partnership lacks the word “strategic”, this suggests the country has no special importance for political or security reasons, or as a source of strategic resources. This does not suggest the country is unimportant. Instead, it indicates the relationship is primarily economic (Wenwei Po, 2015). For example, Singapore has an all-round cooperative partnership with China – a non-strategic partnership (Wai, 2015). Trade with Singapore is very important to China. 1.4 percent of all China’s ex-ports and 2.4 per cent of its imports are linked to Singapore (OEC, 2018). But Singapore is not considered a “strategic” partner. Singapore does not impact China’s border defences or control access to strategic resources. Arguably, neither does Singapore facilitate access to important markets – other trade centres such as Hong Kong could perform this function. All the same, Singapore is important for Chinese business and trade. MFA partnerships indicate aspects of a partnership, but they are not prescriptive.

19More in-depth analysis on non-strategic partnerships is needed. How-ever, this is beyond the scope of this article. Due to their importance for China’s security concerns, this article focuses primarily on strategic partnerships.

20The practical implication of having a “strategic partnership” with China is that facilitation of trade deals, security cooperation, or large, bilateral investment projects becomes more likely (Strüver, 2017, p. 45). It should be noted the partnerships themselves tend to be accompanied by little action at first. “They are not about impact but rather a diplomatic attempt to see whether or not future collaboration might be feasible” (Ibid.). Part-nerships are more about the future potential of closer interaction. When they are signed, there is not an immediate uptick in exchange and co-operation. It simply indicates Beijing is ready to take relations further. Countries increasingly make requests to Chinese diplomats to raise rela-tions from non-strategic to strategic partnerships. More often than not, the MFA indulges these requests (Feng and Huang, 2014, p. 9). All the same, the different levels (numbered 2 to 6 above) among strategic partnerships prevent the system from becoming frivolous. While a country may have their partnership with China upgraded to a strategic partnership, there are five additional levels of strategic partnership, which rank those of most importance for China.

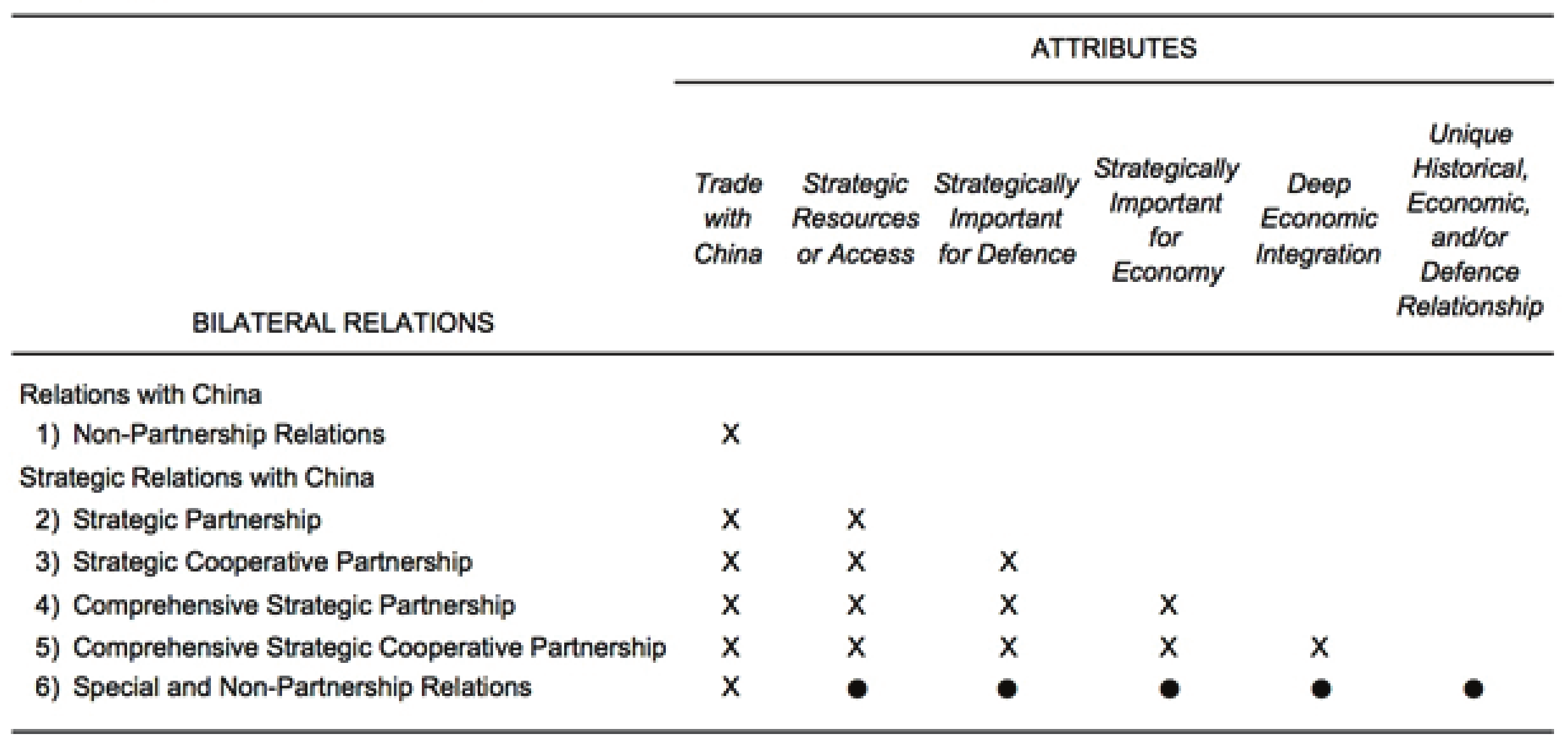

21In general, the level of partnership a country has with China reveals cer-tain attributes about the bilateral relationship. Non-strategic partnership countries have trade with China. Strategic partnerships tend to mean a country has a strategic resource or some form of access to resources or trade that China values. Strategic Cooperative Partnerships are important for reasons of defence. Comprehensive Strategic Partnerships are with countries that are important for the current functioning or future develop-ment of China’s economy. Comprehensive Strategic Cooperative Partner-ships feature countries that are deeply integrated with China’s economy. So far, only Southeast Asian countries (such as Cambodia, Thailand, and Vietnam) have this form of partnership. Finally, countries with Special and Non-Partnership relations with China – for historical, economic, or defence reasons – may have all or a mixture of these attributes (Wenwei Po, 2015; MFA, 2018).

22Table 1 below, “Typology of Chinese Partnership Relations”, arranges the six partnerships and their attributes from least to greatest importance. An “X” indicates the existence of an attribute in a partnership. Bullet points indicate the attribute may or may not be an aspect of the partner-ship, because of its unique status.

23In Eurasia, the highest-level strategic partnerships tend to have the fol-lowing four factors: (1) shared borders with China; (2) close military inter-action; (3) annual trade in strategic resources above USD$1 billion; and (4) the existence of BRI or energy supply projects with China. Non-stra-tegic partnerships do not have these four features2. In its foreign relations with the countries of Eurasia, the evidence suggests China prioritizes the protection of its borders, supplies of strategic resources, and access to new markets and new strategic resources in that order. Non-strategic part-nerships in Eurasia indicate these four features are lacking in the bilateral relationship. Thus, using Eurasia as evidence, there is a direct connection between security concerns and the level of partnership China has with a country.

Table 1 : Typology of Chinese Partnership Relations

24If the partnerships of Eurasian countries are compared against the exist-ence or lack of the four factors above, there are grounds for ranking the most important countries for China’s foreign policy in Eurasia.

25In the above table 2, “China’s Hierarchical Approach to Eurasian Relations”, the first column ranks a country’s importance for China’s foreign relations in Eurasia, 1 being the most important and 14 being the least. The “Country” column immediately to the right names the ranked coun-try. Under “Partnership” are the exact partnerships China has assigned each state. “Type of Partnership” is a simple numbering system to dis-tinguish the different partnerships, which corresponds to the numbered list of partnerships (1-6) above. The most important type of partnership is numbered 6. The five remaining partnership types decrease in importance from 5 down to 1. The final column, “Date of Strategic Partnership”, gives the date when the current form of strategic partnership was assigned to a country. Countries without strategic partnerships are listed as “n/a”.

Table 2 : China’s Hierarchical Approach to Eurasian Relations

|

Hierarchy |

Country |

Partnership |

Type of |

Date of Strategic |

|

of Relations |

Partnership |

Partnership |

||

|

1 |

Pakistan |

All-weather strategic cooperative |

6 |

2015 |

|

partnership relations |

||||

|

2 |

Russia |

Comprehensive strategic partnership |

6 |

2011 |

|

relations |

||||

|

3 |

Kazakhstan |

Comprehensive strategic partnership |

4 |

2011 |

|

4 |

Tajikistan |

Comprehensive strategic partnership |

4 |

2016 |

|

5 |

Kyrgyzstan |

Comprehensive strategic partnership |

4 |

2018 |

|

6 |

Uzbekistan |

Comprehensive strategic partnership |

4 |

2017 |

|

7 |

Belarus |

Comprehensive strategic partnership |

4 |

2013 |

|

8 |

Afghanistan |

Strategic cooperative partnership |

3 |

2012 |

|

9 |

Turkmenistan |

Strategic partnership |

2 |

2013 |

|

10 |

Ukraine |

Strategic partnership |

2 |

2011 |

|

11 |

Azerbaijan |

Non-strategic partnership (Friendly |

1 |

n/a |

|

Cooperation) |

||||

|

12 |

Georgia |

Non-strategic partnership (Friendly |

1 |

n/a |

|

Cooperation) |

||||

|

13 |

Armenia |

Non-strategic partnership (Friendly |

1 |

n/a |

|

and Cooperative) |

||||

|

14 |

Moldova |

Non-strategic partnership (Friendly |

1 |

n/a |

|

Cooperation) |

||||

Source: For titles and dates of partnerships, see MFA (2018).

26The top 1 and 2 spots in the hierarchy above, held by Pakistan and Russia, are essentially interchangeable. Both countries have type 6, “spe-cial partnership relations” with China. The China-Pakistan relationship is continuing to develop. Despite China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) infrastructure projects valuing USD$62 billion (Page and Shah, 2018), economic development is not yet the crux of the Pakistan bilateral relationship. Joint security and stability are the most established and en-during aspects of bilateral interaction (Small, 2015; Ye, 2009, p. 109). In mid-September 2018, deputy chairman of China’s Central Military Com-mission Zhang Youxia said military ties were the “backbone of relations between the two countries” (Reuters, 2018). Reliable supply of raw ma-terials is, perhaps, the biggest motivating factor Russia’s special partner-ship (Maçães, 2018). Pakistan has been given first place, because it more recently had “all-weather” (全天) added to its already special strategic cooperative partnership (Wenwei Po, 2015).

27Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, and Belarus all have type 4, comprehensive strategic partnerships. These countries are ar-ranged first by whether a border is shared with China, second by the value of their 2016 exports to China, and third by the number of bilateral, senior-level military meetings hosted by China from 2013-2016 (OEC, 2018; Allen et al., 2017). They take spots 3 to 7.

28Belarus is the best example of how the BRI has become a determinant of partnership relations. Belarus has no border with China and its trade in strategic resources is mostly irrelevant. Total exports to China in 2016 were slightly more than US$ 400 million (OEC, 2018). What sets Belarus apart is its location along the SREB. Belarus and China are jointly developing the Great Stone Industrial Park, lying south-east of the Belarusian capital, Minsk. It is officially part of the BRI (Li, 2018). This industrial park aims to function as a manufacturing and logistics hub for SREB trade (Republic of Belarus, 2018), which satisfies the security concern to enables access to markets for the BRI. Thus, the BRI and SREB have expanded China’s ambitions and in doing so have extended the scope of strategic locations, which are access points to markets. A month-and-a-half before China unveiled the SREB, Belarus received its Comprehensive Strategic Partnership (MFA, 2018).

29Afghanistan has its rank based on partnership type. It is a type 3, strate-gic cooperative partnership, which focuses more on security and strategic areas and less on the economy, trade, and investment. While it lacks the economic aspects of type 4, comprehensive strategic partnerships, it is more strategically important than the simpler type 2, strategic partner-ship. Afghanistan is placed just below Belarus in spot 7.

30Turkmenistan and Ukraine both have type 2, strategic partnerships. Turkmenistan exports more strategic resources to China than Ukraine does, so it is ranked higher. Turkmenistan gets spot 9 and Ukraine gets spot 10.

31The final four Eurasian countries, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Armenia, and Moldova have type 1, non-strategic partnerships. They have not received strategic partnerships, and thus have “n/a” in the date of strategic partnership column. They have none of the four factors that make for a strategic partnership with China – although China hosted one senior-level, bilateral military meeting with Armenia in December 2013 (Allen et al., 2017). If there any BRI related projects in these countries, they do not yet involve China. For example, the Baku-Tbilisi-Kars railway and Baku International Sea Trade Port in Azerbaijan are meant to complement the BRI, but they do not involve Chinese financing (Humbatov, 2017). The case is the same with Georgia’s Anaklia Black Sea Deep Water Port (Jardine, 2018). Armenia is still seeking Chinese funding for two BRI-related projects: the Armenian Southern Railway, linking to Iran in the South and linking with either Georgia or another state for a route to Europe, and a Georgia-Armenia-Iran Highway (three of the five sections are already built) (Financial Tribune, 2018; Wright, 2017). In Moldova, although China has shown some interest in some power station projects, negotiations are still in the early stages (Liu, 2017). There may be some trade in strategic resources with China, but the volumes are negligible. None of the countries represent strategic partners. These four countries are ordered by first type and then value of their exports to China. Strategic resources take precedence over non-strategic. Next, a greater value of exports is ranked higher. Thus, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Armenia, and Moldova take spots 11, 12, 13, and 14 respectively.

32The hierarchy of partnerships says several things about China’s approach to foreign policy in Eurasia. It reinforces the argument that China values those countries that do most to address its security concerns. It also shows how the BRI is impacting which bilateral relationships matter to China. In general, the hierarchy rankings are predictable. Belarus’s high level partnership with China reflects the gaining importance of the BRI. Thus, the BRI helps rationalise what at first appears to be an outlier in table 2 above. All other Eurasian holders of comprehensive strategic partnerships have shared borders or strategic trade with China; Belarus fits neither of these conditions. As China has increased its commitment to the BRI, so have its relations with Belarus deepened.

33The BRI has affected China’s approach to relations in Eurasia in two ways. First, it has added a new dimension to China’s factors for strategic partnerships – projects with China related to the BRI may help increase the level of partnership with a country. Second, countries not traditionally viewed as strategic have gained new significance, because they represent access to new markets, the prime example being Belarus.

The BRI as Strategic Ambiguity

34This section argues the BRI is a tool of strategic ambiguity. To explain strategic ambiguity, it is best to separate it into its constituent parts. Strat-egy is the management of the resources and methods available to meet objectives (Freedman, 2013, p. xi). Ambiguity is the failure to express a clear position among possible alternatives. Strategic ambiguity, then, is an intentional lack of clarity or deliberate uncertainty in the communi-cation of goals in order to reach an objective (Jarzabkowski et al., 2010).

35In political settings, strategic ambiguity can be highly useful. If there is ambiguity over goals, this means the purpose or aims of these goals can be interpreted in multiple ways. In a complex situation where collective action is needed – such as a large project with many partners – partici-pants can assign their own interpretations of a goal if that goal remains ambiguous. For influential actors, being ambiguous about goals can be used to encourage collective action, because participants involved may arrive at their own interpretations for acting, which do not contradict their own interests (Eisenberg, 1984; Eisenberg and Goodall, 1997). The continent-spanning, multi-country, infrastructure mega-project BRI can-not help but be political. It is exactly the kind of collective action project that strategic ambiguity is suited for.

36When strategic ambiguity and international relations are discussed, two examples tend to be mentioned (Zhang and Han, 2013; Cochran, 1996). The first is the US’s ambiguous stance on using nuclear weapons to man-age Taiwan Straight tensions between Taipei and Beijing. The second contemporary example of strategic ambiguity in international relations is Israel’s nuclear weapons programme. Both these examples involve the ambiguous communication of threat. The ambiguous statements and ac-tions of one actor concerning the use of force causes others to behave more cautiously.

37By contrast, the BRI involves the deliberate unclear communication of goals. Its purpose remains conspicuously unclear. Chinese President Xi Jinping proposed a new Silk Road in September 2013. No clear aim was put forward other than “to forge closer economic ties, deepen coopera-tion and expand development space in the Eurasian region” (Witte, 2013). China’s new Silk Road has expanded into the BRI, but this goal ambiguity persists. Chinese politicians describe the BRI’s purpose as a “community of common destiny” (Zhang, 2018). This description is “vague in mean-ing and loosely used by China” (Ibid.).

38The goal ambiguity of the BRI relates more closely to organisation theory and communication studies, rather than the ambiguity of threat covered in international relations literature. Strategic ambiguity was first presented by Eisenberg (1986) as a form of communication that accommodates a di-versity of goals, while facilitating change and preserving positions of lead-ership. Within the context of a large-scale project with many members, ambiguity can be both an asset and a liability. In certain ways, ambiguity can prevent collective action. Because goals are unclear, organisations might engage in planning processes that have little relevance to other organisational members (Middleton-Stone and Brush, 1996), or progress is incremental due to tension among members over the purpose of their actions (Vaara et al., 2003; Wallace and Hoyle, 2006). In ambiguous contexts, agreement among actors is difficult, because of the often var-ying aims different actors bring (Huxham and Vangen, 2000). However, another branch of literature argues ambiguity can be an asset (Eisenberg, 1984; Eisenberg and Goodall, 1997; Davenport and Leitch, 2005). When used strategically – for example, when it is skillfully managed, like a re-source – “ambiguity enables different constituents to attribute different meanings to the same goal, or for powerful actors to construct different meanings for any given goal according to the interests of their audience” (Jarzabkowski et al., 2010).

39The strategy behind this form of goal ambiguity has been compared to Deng Xiaoping’s “crossing rivers by feeling the stones” reform approach (Deng, 1983; Yu, 2018). A lack of clear aims and guidelines suits China’s pragmatic approach for the development of the BRI. It enables the par-ties involved to make adjustments during the implementation process. But “Deng used this tactic when China was isolated in the immediate aftermath of the Cultural Revolution, whereas Xi needs the involvement of over 60 countries for his vision” (Yu, 2018, pp. 7-8). That is, strategic ambiguity is useful for setting a large-scale project in motion, because it provides a mechanism to fine tune. But it is unlikely to be appropriate for the long-term development of the BRI as more participants join and require guidance toward a shared aim.

40In general, the BRI exemplifies China’s gaining ability to set the glob-al agenda. Since the BRI’s announcement, China has become Eurasia’s most attractive foreign development and investment partner (Olcott, 2013; Szczudlik-Tatar, 2013, 4; Gabuev, 2017. By May 2017, 58 state representatives (including 29 heads-of-state) attended the Belt and Road Forum in Beijing, which laid out President Xi’s USD$900 billion vision to build a modern-day version of the ancient Silk Road (Phillips, 2017; The Diplomat, 2017).

41The BRI is a tool of strategic ambiguity. Chinese officials repeatedly state the aim of the BRI is to increase “connectivity”: “political”, “trade”, “financial”, “infrastructure”, and “people-to-people connectivity” (Xi, 2017; Wang, 2018). In Eurasia, increased connectivity tends to mean the “promotion of new developmental projects designed to connect with [China’s] underdeveloped and restive province of Xinjiang” (Cooley, 2016, p. 4). But what form this increased connectivity takes and what use it is put to both remain unclear (Financial Times, 2017). Therefore, the BRI is a tool of strategic ambiguity, because its purpose remains vague. In this way, BRI becomes a platform for almost any kind of political, trade, financial, infrastructure, or people-to-people interaction with China.

42Using the BRI as a tool of strategic ambiguity is meant to provide China with flexibility and a wide range of options in defining its presence abroad. But it does have its problems. Outside of increased connectivity, China has yet to state what participation in the BRI means in practice and what China’s function within it will be. Certain influential international players, such as the US, India, and several EU members including Germany, are cautious over participation in the BRI, partly because they are unsure of Beijing’s intentions. In addition, this lack of a clear stance makes room for negative narratives to fill the void. For example, in a speech at the Rhode Island Naval War College in June 2018, Secretary of Defense James Mattis alerted listeners the BRI represents China’s “long-term designs to rewrite the existing global order… to replicate on the international stage their authoritarian domestic model… while using predatory economics of piling massive debt on others” (Mattis, 2018). In January 2018, French President Emmanuel Macron gave a similar warning that the BRI “cannot be the roads of a new hegemony that will make the countries they traverse into vassal states” (The Economist, 2018). In these cases, the BRI’s ambiguity is creating hesitancy for wider engagement.

43On the upside, the BRI remains an expansive concept, which holds real and potential benefits. The Chinese government continually emphasizes the “win-win” and cooperative nature of the BRI for all parties involved (Huangfu and Wang, 2015; Ren, 2015). China’s partners stand to poten-tially benefit from new infrastructure, increased cross-border trade, and deeper interaction with China. However, China does not define a clear vision of the BRI. This is deliberate and it is the BRI’s greatest strength. The time horizons for the completion of BRI are so great, and the goal is so unclear, that China will be able to adjust them according to its own needs. It is strategic ambiguity on a grand scale.

44Chinese Vice President Wang Qishan gave a speech on his 24-29 May, 2018, trip to Russia and Belarus, which shows the purpose of the BRI is still vague as ever. Addressing the Saint Petersburg Economic Forum, Wang stated the BRI “is a new platform of international cooperation ini-tiated by China. [China is] ready to connect with all-comers for joint-ne-gotiation, joint-construction and joint-use of benefits in order to add mo-mentum to the joint development of the planet” (The Kremlin, 2018). This statement implies that through connectivity, the BRI is all things to all stakeholders. His words maintain the lack of clarity surrounding the BRI.

45The authors of this paper assert this vague approach to outlining the BRI’s location and purpose is deliberate. The ambiguity over the BRI’s central purpose makes it a highly flexible tool for use in bilateral and multilateral dialogues. In practice, this means Chinese negotiators can position the BRI as a platform to put forward almost any form of bilateral agenda. For example, approximately 86 countries and international or-ganizations have signed BRI cooperation agreements with China, includ-ing countries as varied as Tonga, Panama, Belarus, and Pakistan (China Daily, 2017; Xinhua, 2018). Italy – an EU member country – is currently negotiating with China on its own BRI cooperation agreement (Reuters, 2019). In the words of one financial analyst, “BRI is progressing fast if you value the number of projects that China has financed, some of which are extremely relevant in terms of improving physical connectivity at a global level. So far there are around US$350 billion worth of projects financed” (Walker, 2018). All manner of projects in all manner of external locations can count as increasing connectivity.

46As Professor of Geography at the Chinese Academy of Sciences Liu Weidong stated in 2014, “one of the key ‘misconceptions of [the BRI]’… pertains to the conceptualisation of the project as comprising well defined, fixed, and predetermined (maritime and land) routes and transects… [T]he initiative should be seen as an ‘abstract and metaphorical concept’… to establish a platform for regional and global economic cooperation” (Sidaway and Woon, 2017, pp. 592-593). This thinking is how China’s new Silk Road can include countries and projects the world around.

47Thus, the very point of the BRI is ambiguity. The more possibilities for the BRI, the more flexible and versatile it becomes. An opinion piece by Forbes columnist Wade Shepard (2017) reaches the same conclusion:

If you’re looking for an official, correct map of where China’s Belt and Road actually goes, good luck. If you’re looking for an official explanation of what it really is… you’ve just jumped down into a very deep hole of misinformation, no information, and all out propaganda… The vagueness, lack of institutionalization, and very broad definition of the China’s Belt and Road is probably one of its greatest strengths… This initiative is flex-ible enough to evolve with the times, blow in the direction of contrasting political winds, and ride out the inevitable cycles of the global economy.

48One result of strategic ambiguity has been difficulty over how to de-fine the BRI. Sidaway and Woon (2017) have written an excellent article summarising the varying definitions of the BRI among Chinese scholars. Gabuev (2017) argues the “‘Belt and Road’ concept has become so in-flated, that it’s no longer helpful in understanding anything about China’s relationship with the outside world, but only further obscures an already complicated picture”. This confusion is the very point of strategic ambigu-ity; participants within the BRI will base their opinions and reactions on their own interpretations of China’s political obscurity.

49In early 2018, concerns over rising debt cast doubt on the BRI’s long-term viability. The ambitious size of certain BRI infrastructure projects can be costly for participant countries to take part in. The majority of countries that span the vast distances of the SREB have low or lower-mid-dle income economies (World Bank, 2017). There is growing uncertainty that participant countries will be able to repay Chinese loans for BRI pro-jects. For example, Pakistan – the country with the highest value of BRI projects at USD$62 billion – appears unable to repay China for capital goods (that is, goods intended for production and construction, rather than final consumption), much of which were loaned for BRI-related pro-jects (Page and Shah, 2018).

50The emerging economies of Eurasia appear at particular risk of debt non-repayment. The OECD Country Risk Classification system measures the likelihood of a country imposing capital and convertibility controls, or the chance force majeure (e.g. war, expropriation, revolution, civil dis-turbance, floods, or earthquakes) disrupts debt repayment for businesses. A grade of 7 is the greatest level of risk assigned by the OECD system. 3.5 is the average risk grade for world emerging markets. Pakistan, Tajikistan, Afghanistan, Kyrgyzstan, Ukraine, and Moldova all have risk grades of 7 (OECD, 2018). Of the 14 Eurasian countries studied here, the average risk grade among them is 6.2. So, there is a genuine risk of debt repayment crises for BRI participants in Eurasia.

51There is much debate whether working with China produces sustainable development. The experience of China’s engagement with developing African countries is central to this discussion. Supporters of Chinese development practices – which often concerns comprehensive packages of aid, trade, investments and loans (Alden, 2007) – argue China’s pragma-tism and win-win approach provides developing countries in Africa the “help to self-help” (Abeselom, 2018, p. 419). This contrasts with “West-ern” development assistance, which often attaches conditionality that can intrude on Westphalian state sovereignty norms (Ibid.). Skeptics ar-gue China’s pragmatic approach ignores best practices and global stand-ards. This can increase administrative burdens and transaction costs for African governments, because they must adhere to different obligations from multiple partners (Bracho and Grimm, 2016). Another argument is that China’s use of market interest rates for loans, instead of lower, con-cessional rates applied by established lenders, burdens recipients. On the plus side, the addition of Chinese financing provides African countries with extra bargaining power (Fraser and Whitfield, 2009; Mohan and Lampert, 2013). As the BRI evolves and expands, China’s management of international developments is being tested in new ways.

52As a rule, China pursues a policy of “value for money” for its aid and loans. Whether in the form of loan-for-resources, or tied aid (where aid must be used for Chinese goods and services), or tax breaks for projects related to concessional loans, Chinese finance aims to be development sustainable, not just debt sustainable (Brautigam, 2009, pp. 78-80, pp. 185-186). That is, China promotes development in hopes of repay-ment from the development itself, “rather than waiting a long time and paying year-by-year” (Ibid., p. 186). Thus, a guiding principle for the var-ious forms of Chinese finance and aid is to continue development in the short-term to ensure debt sustainability in the long-term.

53In the context of the BRI, some of China’s efforts to promote development sustainability in the short-term have drawn strong criticism. Sri Lanka recently conducted a debt-for-equity swap to handle BRI-related debts to China. In 2011, Tajikistan wrote off an unknown amount of debt by giving China 1,158 square kilometres of disputed territory (Hurley et al., 2018, p. 20). For foreign affairs hawks, these are signs of “debt-trap diplomacy”. This insinuates countries are mortgaging their resources, strategic assets, and sovereignty for Chinese financing. The expression arose after Indian strategic commentator Brahma Chellaney (2017) used it to criticise the BRI as a platform for bad investments that serve Chinese geopolitical aims.

54The BRI represents a new chapter in Chinese debt and development sustainability. If China’s past dealings with African debt problems are to serve as a guide, debt forgiveness may be part of Beijing’s initial BRI adjustments. China forgave a considerable amount African debt during the 2000s (Copper, 2016, p. 83, p. 148). But the Chinese government dealt with these issues in an ad hoc, case-by-case manner; China has no standard guide or practice for debt management (Hurley et al., 2018, pp. 19-20). In addition, China tends not to disclose the details of its relief arrangements to debtor countries (Lahtinen, 2018, p. 38; Copper, 2016, pp. 146-148). But the value of today’s BRI investments are much larger than African debts to China during the 2000s. The forgiven debts were in the tens and hundreds of millions of US dollars, and not billions like to-day’s BRI debts in Pakistan and Sri Lanka (Hurley et al., 2018, pp. 29-32). Debt-for-equity swaps (like in Sri Lanka and Tajikistan described above) so criticised by foreign observers are a recent feature of Chinese debt handling. So while BRI enthusiasts may claim China’s actions show efforts at development sustainability, it is too early to tell. Debt-trap diplomacy may come to define development of the BRI.

55However, worries over the BRI’s financial sustainability are unlikely to stop the initiative, only slow it. This is because strategic ambiguity ena-bles Beijing to adjust the BRI on the fly. The BRI is still in its early stages; and its shaping is still malleable. Officials in Beijing are said to be re-as-sessing investments to “ensure that the reputation of the BRI is safeguard-ed by making sure that BRI projects are high quality” (Kynge, 2018). In mid-September 2018, top Chinese think tank experts and government officials said China was open to adjustments to BRI projects according to countries’ needs (Shen, 2018). Indeed, there are rumours that a renego-tiation of CPEC is underway between China and Pakistan (Gupta, 2018).

56Eurasian nations in general remain enthusiastic about the SREB. Regardless of debt fears, analysts argue Eurasian countries see it as the biggest show in town. “Central Asian countries are in need of large-scale investments and the BRI intends to do just that” (Hashimova, 2018). Despite a lack of clarity over the purpose of the SREB, Eurasian governments tend to be very supportive of current and future Chinese investments (Pantucci and Lain, 2016, pp. 47-48; Chen, 2018). Indeed, its vagueness is part of the very nature of the BRI. As one high-level Kazakh official reflected, “The SREB is a platform, but not everything has been decided yet. Kazakhstan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs completely supports the project” (Pantucci and Lain, 2016, p. 47, p. 50). An inability to repay debts will likely represent a renegotiation of terms rather than the failure of BRI projects – which appears to be the case developing in Pakistan. So long as the aim of the BRI remains vague and the future gains seem big, China will have plenty of willing partners, regardless of the changes China may decide to make.

57Thus, in Eurasia and elsewhere, the BRI is a tool of strategic ambiguity to encourage collective action on Chinese terms. For the countries of Eurasia, despite the lack of clarity over the substance of the BRI, potential economic gains from BRI developments continue to attract. To this end, the vagueness of the BRI enables Chinese officials to adjust its devel-opment approach to react to changing circumstances within participant countries. However, strategic ambiguity is unlikely to be conducive to the long-term development of the BRI. As demonstrated above, certain influ-ential members of the international community, such as the US, India and EU member states, want to establish what China’s terms are before they engage with the project. For wider participation of in the BRI, ambiguity over China’s goals for the project must eventually be removed.

Conclusion

58This paper has provided brief responses to two fundamental questions surrounding China’s growing presence in Eurasia: (1) What is China’s approach to foreign policy in Eurasia? (2) What role does the BRI play in China’s foreign policy?

59Answering first question, the authors argued China’s approach to Eurasia is linked to factors that address Chinese security concerns. This approach is visible in the bilateral partnerships it forms with Eurasian countries. The hierarchy these partnerships form show two things. First, it supports ear-lier arguments that link China’s approach to foreign policy in Eurasia to satisfying security concerns. Second, the BRI is changing which bilateral relationships matter to China. While China has not altered its approach to foreign policy in Eurasia, new goals – like facilitating the BRI – have widened the range of strategic relationships.

60The response to the second question argues the BRI functions as a tool of strategic ambiguity within China’s foreign policy. Chinese officials are deliberately ambiguous about the nature and purpose of the BRI. The vagueness is a strategic. It helps to generate support for the BRI, which de-mands collective action among multiple partner states across continents. The potential gain by participation in the BRI justifies Eurasian countries’ involvement in a project whose aim is unclearly defined. In addition, a lack of clarity over the BRI enables Chinese officials to adjust the initia-tive in accordance to changing, global circumstances. Because the BRI’s purpose is unclear, it gives Chinese foreign policy makers a degree of freedom in adjusting what terms and conditions participants must meet for the success of the initiative.

61But ambiguity brings problems, too. Some potential participants are re-luctant to join the BRI, because the lack of clarity over its purpose. This lack of clarity has bred and fed criticism of the initiative. Detractors claim the BRI is Trojan Horse for Chinese debt-trap diplomacy. China’s man-agement of debt and development in Africa can only offer limited insight to how China will address the issue of the BRI’s long-term sustainability. For the time being, strategic ambiguity is useful, because the Chinese government can adjust its management of the project spontaneously. It is likely that strategic ambiguity is not a good approach for the long-term, however, because wider participation and more stable development will require joint agreement of shared aims.

References

62Abeselom, K. (2018), “The Impact of Foreign Aid in Sustainable Devel-opment in Africa: A Case Study of Ethiopia”, Open Journal of Political Science, 8, pp. 365-422.

63Agadjanian, V. and Gorina, E. (2018), “Economic Swings, Political In-stability and Migration in Kyrgyzstan”, European Journal of Popula-tion, [published 20 March 2018], pp. 1-20. Available at: https://doi. org/10.1007/s10680-018-9482-4 (accessed 30 September 2018).

64Alden, C. (2007), China in Africa, London: Zed Books.

65Allen, K., Saunders, P. C., and Chen, J. (2017), Chinese Military Diplo-macy, 2003-2016: Trends and Implications, Washington, DC: National Defense University Press.

66Bracho, G. and Grimm, S. (2016), “South-South Cooperation and Frag-mentation – a non-issue?” in Klingebiel, S., Mahn, T. and Negre, M. (eds), The Fragmentation of Aid: Concepts, measurements and implica-tions for development cooperation, London: Palgrave Macmillan.

67Brautigam, D. (2009), The Dragon’s Gift: The Real Story of China in Africa, New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

68Chellaney, B. (2017), “China’s Debt-Trap Diplomacy”, Project Syndicate, 23 January. Available at: https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/ china-one-belt-one-road-loans- debt-by-brahma -chellaney-2017-01?barrier=accesspaylog (accessed 13 March 2019).

69Chen, Y. Y. (2018), Caspian Region in the Silk Road Economic Belt (SREB): A Chinese Perspective. Washington DC: Caspian Policy Center. Available at: http://www.caspianpolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/ Caspian-Region-in-the-Silk-Road -Economic -Belt-SREB_-A-Chinese-Perspective-CPC.pdf (accessed 28 September 2018).

70Cheng, J. Y. S. and Wankun, Z. (2002), “Patterns and Dynamics of China’s International Strategic Behaviour”, Journal of Contemporary China, 11: 31, pp. 235-260.

71China Daily (2017), “China signs cooperation agreements with 86 en-tities under Belt and Road”, China Daily, 23 December. Available at: http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/201712/23/WS5a3dbf9da31008cf-16da306e.html (accessed 5 June 2018).

72Cochran, E. S. (1996), “Deliberate ambiguity: An analysis of Israel’s nuclear strategy”, The Journal of Strategic Studies, 19: 3, pp. 321-342.

73Copper, J. F. (2016), China’s Foreign Aid and Investment Diplomacy, Vol-ume III: Strategy Beyond Asia and Challenges to the United States and the International Order, New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

74Cooley, A. (2016), The Emerging Political Economy of OBOR. The Chal-lenges of Promoting Connectivity in Central Asia and Beyond, Avail-able at: https://csis-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/publica-tion/161021_Cooley_OBOR_Web.pdf (accessed 30 August 2018).

75Cowhig, D. (2017), “China’s Diplomacy: How Many Kinds of Major and Minor Partner ‘Relations’ 夥伴關係 Does China Have?”, 高大伟 David Cowhig’s Translation Blog, 4 July. Available at: https://gaodawei. wordpress.com/2017/04/07/chinas-diplomacy-how-many-kinds-of-major- and-minor-partner-relations-夥伴關係-does-china-have/ (accessed 28 June 2018).

76Dai, W. L. (2016), “China’s Strategic Partnership Diplomacy” (Du Weiwei, Trans.), Contemporary International Relations [现代国际关系], 26: 1, pp. 101-116.

77Davenport, S. and Leitch, S. (2005), “Circuits of power in practice: Stra-tegic ambiguity as delegation of authority”, Organization Studies, 26: 11, pp. 1603-1623.

78Deng, X. (1983), Selected Works Vol. 2 (1975-1982). People’s Publish-ing House: Beijing. Available at: https://dengxiaopingworks.wordpress. com/selected-works-vol-2-1975-1982/ (accessed 13 March 2019).

79Detsch, C. (2018), “China’s Belt and Road Initiative opens to Latin America”, Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, 15 February. Available at: https:// www.fes-connect.org/trending/chinas-belt-and-road-initiative-opens-to-latin-america/ (accessed 5 June 2018).

80Eisenberg, E. M. (1984), “Ambiguity as strategy in organizational com-munication”, Communication Monographs, 51: 3, pp. 227-242. Avail-able at: https://doi.org/10.1080/03637758409390197 (accessed 6 June 2018).

81Eisenberg, E. M. and Goodall, H. (1997), Organizational Communica-tion: Balancing Creativity and Constraint, New York: St Martin’s Press.

82Feng, Z. P. and Huang, J. (2014), “China’s strategic partnership diploma-cy: engaging with a changing world”, Fundación para las Relaciones Internacionales y el Diálogo Exterior (FRIDE), Working Paper 8, June 2014. Available at: http://fride.org/download/wp8_china_strategic_ partnership_diplomacy.pdf (accessed 9 July 2018).

83Financial Times (2017), “One Belt, One Road – and many questions”, Financial Times, 14 May. Available at: https://www.ft.com/content/ d5c54b8e-37d3-11e7-ac89-b01cc67cfeec (accessed 23 July 2018).

84Financial Tribune (2018), “China Interested in Iran-Armenia Rail Project”, Financial Tribune, 6 March. Available at: https://financialtribune.com/ articles/economy-business-and-markets/83024/china-interested-in-iran-armenia-rail-project (accessed 28 June 2018).

85Fraser, A. and Whitfield, L. (2009), “Understanding Contemporary Aid Re-lationships”, in Whitfield, L. (ed.), The Politics of Aid. African strategies for dealing with donors, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

86Freedman, L. (2013), Strategy: A History, New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

87Gabuev, A. (2017), “Belt and Road to Where?”, Moscow Carnegie Center, 8 December. Available at: http://carnegie.ru/2017/12/08/belt-and-road-to-where-pub-74957 (accessed 5 June 2018).

88Gupta, A. (2018), “Pakistan Confirms the Bugs in the Architecture of China’s ‘Belt and Road’”, World Politics Review, 27 September. Available at: https://www.worldpoliticsreview.com/articles/26123/ pakistan-confirms -the-bugs- in-the-architecture-of-china-s-belt-and-road (accessed 28 September 2018).

89Hashimova, U. (2018), “Why Central Asia Is Betting on China’s Belt and Road”, The Diplomat, 13 August. Available at: https://thediplomat. com/2018/08/why-central-asia-is-betting-on-chinas-belt-and-road/ (ac-cessed 15 September 2018).

90Heath, T. R. (2012), “What Does China Want? Discerning the PRC’s Na-tional Strategy”, Asian Security, 8: 1, pp. 54-72.

91Hillman, J. E. (2018), “China’s Belt and Road Is Full Of Holes”, Center for Strategic International Studies, 4 September. Available at: https://www. csis.org/analysis/chinas-belt-and-road-full-holes (accessed 13 March 2019).

92Huangfu, P. L. and Wang, J. J. (eds) (2015), “Ruhe zouhao yidaiyilu jiaoxiangyue” [How to play the One Belt, One Road symphony well], liaowang [瞭望], 18 March. Available at: http://news.swjtu.edu.cn/ shownews-9904-0-1.shtml (accessed 24 July 2018).

93Humbatov, M. (2018), “Azerbaijan within the Context of the Silk Road”, International Policy Digest, 5 April. Available at: https://intpolicydigest. org/2018/04/05/azerbaijan-within-the-context-of-the-silk-road/ (accessed 28 June 2018).

94Hurley, J., Morris, S. and Portelance, G. (2018), “Examining the Debt Implications of the Belt and Road Initiative from a Policy Perspective”, Center for Global Development Policy Paper 121, March 2018. Available at: https://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/examining-debt-implications-belt-and-road-initiative-policy-perspective.pdf (accessed 1 September 2018).

95Huxham, C. and Vangen, S. (2000), “Ambiguity, complexity and dy-namics in the membership of collaboration”, Human Relations, 53: 6, pp. 771-806.

96ICBC (2017), Belt and Road China Connectivity Index, ICBC Standard Bank, July 2017. Available at: https://www.oxfordeconomics.com/icbc-standard-bank-belt-and-road-economic-indices-oe (accessed 9 July 2018).

97Jardine, B. (2018), “With Port Project, Georgia Seeks Place on China’s Belt and Road”, Eurasianet, 21 February. Available at: https://eurasianet. org/s/with -port-project-georgia-seeks-place-on-chinas-belt-and-road (accessed 28 June 2018).

98Jarzabkowski, P., Sillince, J. and Shaw, D. (2010), “Strategic ambiguity as a rhetorical resource for enabling multiple strategic goals”, Human Relations, 63: 2, pp. 219-248.

99Kynge, J. (2018), “China’s Belt and Road projects drive overseas debt fears”, Financial Times, 7 August. Available at: http://: https://www. ft.com/content/e7a08b54-9554-11e8-b747-fb1e803ee64e (accessed 1 September 2018).

100Lahtinen, A. (2018), China’s Diplomacy and Economic Activities in Africa: Relations on the Move, Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.

101Li, J. (2018), ‘Spotlight: China-Belarus Industrial Park Sees Rapid Development’, Xinhua News Agency. 14 May. Available at: http://www.xinhuanet.com/ english/2018-05/14/c_137178753.htm (accessed 13 March 2019).

102Li, L. F. and Pantucci, R. (2013), “Decision time for Central Asia: Russia or China?”, Open Democracy, 24 January. Available at: https://www. opendemocracy.net/od-russia/li-lifan-raffaello-pantucci/decision-time-for-central-asia-russia-or-china (accessed 12 July 2018).

103Liu, Z. (2017), “Can a China-Moldova free-trade deal give Beijing a foothold in eastern Europe?”, South China Morning Post, 29 December. Available at: http://www.scmcom/news/china/diplomacy-defence/ article/2126179/can -china-moldova-free-trade-deal-give-beijing-foothold (accessed 28 June 2018).

104Maçães, B. (2018), Dawn of Eurasia: Following the New Silk Road, London, UK: Allen Lane.

105Mattis, J. N. (2018), “Remarks By Secretary Mattis at the U.S. Naval War College Commencement”, U.S. Department of Defense, 15 June. Available at: https://dod.defense.gov/News/Transcripts/Transcript-View/ Article/1551954/remarks-by-secretary-mattis-at-the-us-naval-war-college-commencement-newport-rh/ (accessed 11 November 2018).

106MFA (2014), Countries and Regions, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China. Available at: http://www.fmprc.gov.cn/ mfa_eng/gjhdq_665435/ (accessed 28 June 2018).

107Middleton-Stone, M. and Brush, C. (1996), “Planning in ambiguous contexts: The dilemma of meeting needs for commitment and demands for legitimacy”, Strategic Management Journal, 17: 8, pp. 633-652.

108Mohan, G. and Lampert, B. (2013), “Negotiating China: Reinserting African agency into China-Africa Relations”, African Affairs, 112: 446, pp. 92-110.

109OEC (2018), [Interactive “Tree Map” showing countries arranged by con-tinental regions and the percentages of the origins of Chinese imports and the destinations of Chinese exports] Countries: China, Observatory of Economic Complexity. Available at: https://atlas.media.mit.edu/en/ profile/country/chn/ (accessed 10 July 2018).

110OECD (2018), Country Risk Classifications of the Participants to the Ar-rangement on Officially Supported Export Credits, dataset, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Available at: http://www. oecd.org/trade/xcred/cre-crc-current-english.pdf (accessed 13 September 2018).

111Olcott, M. B. (2013), “China’s Unmatched Influence in Central Asia”, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 18 September. Available at: https://carnegieendowment.org/2013/09/18/china-s-unmatched-influence-in-central-asia-pub-53035 (accessed 5 June 2018).

112Pantucci, R. and Lain, S. (2016), ‘IV. Perception Problems of the Belt and Road Initiative from Central Asia, Whitehall Papers, 88: 1, pp. 47-55.

113PDWP [Peaceful Development White Papers] (2011), ‘China’s Peaceful Development’, PRC Information Office of the State Council, 6 Septem-ber. Available at: http://english.gov.cn/archive/white_paper/2014/09/09/ content_281474986284646.htm (accessed 24 July 2018).

114Phillips, T. (2017), “China’s Xi lays out $900bn Silk Road vision amid claims of empire-building”, The Guardian, 14 May. Available at: https:// www.theguardian.com/world/2017/may/14/china-xi-silk-road-vision-belt-and-road-claims-empire-building (accessed 8 June 2018).

115Putz, C. (2018), “Kyrgyzstan Navigates Domestic Political Firestorm, Hopes to Avoid Burning China”, The Diplomat, 7 June. Available at: https:// thediplomat.com/2018/06/kyrgyzstan-navigates -domestic-political-firestorm-hopes-to-avoid-burning-china/ (accessed 12 July 2018).

116Ren, Y. (2015), “Yidaiyilu shi jiaoxiangyue, bushi duzouqu” [One Belt, One Road is a symphony, not a solo piece], Renmin Ribao, 18 March. Avail-able at: http://world.people.com.cn/n/2015/0318/c1002-26714292.html (accessed 24 July 2018).

117Ring, P. S. and Perry, J. (1985), “Strategic management in public and pri-vate organizations: Implications of distinctive contexts and constraints”, Academy of Management Review, 10, pp. 276-286.

118Reuters (2018), “China says military ties ‘backbone’ to relations with Pakistan”, Reuters, 19 September, Available at: https://uk.reuters.com/ article/uk-china-pakistan-defence/china-says-military- ties -backbone-to-relations-with-pakistan-idUKKCN1LZ03V (accessed 25 September 2018).

119Reuters (2019), “Italy wants to sign Belt and Road deal to help exports deputy PM”, Reuters, 10 March. Available at: https://uk.reuters.com/ article/uk-china-italy-belt-and-road/italy-wants-to-sign-belt-and-road-deal-to-help-exports-deputy-pm-idUKKBN1QR0IZ (accessed 13 March 2019).

120Republic of Belarus (2018), “Industrial Park Great Stone”, Official Web-site of the Republic of Belarus. Available at: http://www.belarus.by/en/business/business-environment/industrial-park-great-stone (accessed 13 March 2019).

121Shen, W. D. (2018), “China open to adjustment of B&R projects based on countries’ needs: analysts”, Global Times, 13 September. Available at: http://www.globaltimes.cn/content/1119564.shtml (accessed 28 Sep-tember 2018).

122Shepard, W. (2017), “Why The Ambiguity Of China’s Belt And Road In-itiative Is Perhaps Its Biggest Strength”, Forbes Magazine, 19 October. Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/wadeshepard/2017/10/19/ what-chinas-belt-and-road-initiative-is-really-all-about/ - 2186423ee4de (accessed 12 June 2018).

123Sidaway, J. D. and Woon, C. Y. (2017), “Chinese Narratives on ‘One Belt, One Road’ (一带一路) in Geopolitical and Imperial Contexts”, The Pro-fessional Geographer, 69: 4, pp. 591-603.

124Small, A. (2015), The China-Pakistan axis: Asia’s new geopolitics, New York: Oxford University Press.

125Strüver, G. (2017), “The Chinese Journal of International Politics”, The Chinese Journal of International Politics, 10: 1, pp. 31-65.

126Szczudlik-Tatar, J. (2013), “China’s New Silk Road Diplomacy”, The Polish Institute of International Affairs, No 34 [82], December 2013. Available at: https://www.pism.pl/files/?id_plik=15818 (accessed 24 July 2018).

127The Diplomat (2017), “Belt and Road Attendees List”, The Diplomat, 12 May. Available at: https://thediplomat.com/2017/05/belt-and-road-attendees-list/ (accessed 10 July 2017).

128The Economist (2018), “China’s belt-and-road plans are to be welcomed– and worried about”, The Economist, 26 July. Available at: https:// www.economist.com/leaders/2018/07/26/chinas-belt-and-road-plans-are-to-be-welcomed-and-worried-about (accessed 13 March 2019).

129The Kremlin (2018), “‘Plenarnoe zasedanie Peterburgskogo mezhdunarodnogo ekonomicheskogo foruma’ [St Petersburg International Economic Forum plenary session]”, Prezident Rossii, 25 May. Available at: http://kremlin.ru/ events/president/news/57556 (accessed 5 June 2018).

130Vaara, T. J. and Santti, R. (2003), “The international match: Metaphors as vehicles of social identity-building in cross-border mergers”, Human Relations, 56: 4, pp. 419-451.

131Wai, A. (2015), “Singapore, China Establish All Round Cooperative Partnership”, TODAYonline, 7 Nov. Available at: https://www.todayonline. com/singapore/singapore-china-establish-all-round-cooperative-partnership (accessed 10 September 2018).

132Walker, R. (2018), “Is China’s ambitious Belt and Road Initiative a risk worth taking for foreign investors?”, South China Morning Post, 11 March. Available at: https://www.scmp.com/business/companies/ article/2136372/chinas-ambitious-belt-and-road-initiative-risk-worth-taking (accessed 13 March 2019).

133Wallace, M. and Hoyle, E. (2006), “An ironic perspective on public ser-vice change”, in Wallace M., Fertig M., and Schnellere E. (eds), Manag-ing Change in Public Services, Oxford: Blackwell, pp. 75-94.

134Wang, Yi (2018), “Wang Yi: Take Joint Construction of the ‘Belt and Road’ as Opportunity to Realize Transoceanic Handshake between China and LAC”, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, 23 January. Available at: http://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/zxxx_662805/ t1528760.shtml (accessed 23 July 2018).

135Wenwei Po (2015), “Zhōngguó yǔ dàxiǎo huǒbàn yǒu duōsh ǎo zhǒng guānxì” [China and Its Partners Have How Many Types of Rela-tions?], Wenwei Po, 22 April. Available at: http://news.wenweipo. com/2015/04/22/IN1504220007.htm (accessed 28 June 2018).

136Witte, M. (2013), “Xi Jinping Calls For Regional Cooperation Via New Silk Road”, The Astana Times, 11 September. Available at: https:// astanatimes.com/2013/09/xi-jinping-calls-for-regional-cooperation-via-new-silk-road/, 3 June 2018.

137Woodhouse, A. (2018), “China outlines plans for ‘Polar Silk Road’ in Arctic”, The Financial Times, 26 January. Available at: https://www. ft.com/content/a53ebabc-0268-11e8-9650-9c0ad2d7c5b5 (accessed 5 June 2018).

138World Bank (2017), World Bank Country and Lending Groups, World Bank. Available at: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/ articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups (accessed 27 September 2018).

139Wright, C. (2017), “Making sense of Belt and Road – The Belt and Road country: Armenia”, Euromoney, 26 September. Available at: https:// www.euromoney.com/article/b14t180fwf28pm/making-sense- of-belt-and-road-the-belt-and-road-country-armenia (accessed 28 June 2018).

140Xi, J. P. (2017), “Full text of President Xi’s speech at opening of Belt and Road forum”, Xinhua News Agency, 14 May. Available at: http://www.xinhuanet. com/english/2017-05/14/c_136282982.htm (accessed 23 July 2018).

141Xinhua (2017), “Commentary: China-Panama relations set to open new ho-rizons”, Xinhua News Agency, 17 November. Available at: http://www. xinhuanet.com/english/2017-11/17/c_136760992.htm (accessed 5 June 2018).

142Xinhua (2018), “China, Tonga agree to promote strategic partnership”, Xinhua News Agency, 2 March. Available at: http://www.xinhuanet. com/english/2018-03/02/c_137009307.htm (accessed 5 June 2018).

143Ye, H. L. (2009), “China-Pakistan Relationship: All-Weathers, But Maybe Not All-Dimensional”, in Zetterlund, K. (ed.), Pakistan – Consequences of Deteriorating Security in Afghanistan, Stockholm: Swedish Defence Research Agency, pp. 108-130.

144Yeliseyev, A. (2013), “Some Aspects of Belarusian-Chinese Relations in the Regional Dimension: Much Sound and Little Sense”, Belarusian Institute for Strategic Studies, Report No. SA #08/2013RU, 9 April, 2013. Available at: http://belinstitute.eu/sites/biss.newmediahost.info/ files/attached-files/BISS_SA08_2013en.pdf (accessed 9 July 2018).

145Yu, J. (2018), “The belt and road initiative: domestic interests, bureau-cratic politics and the EU-China relations”, Asia Europe Journal. DOI: 10.1007/s10308-018-0510-0

146Zetterlund, K. (ed.), Pakistan – Consequences of Deteriorating Security in Afghanistan, Stockholm: Swedish Defence Research Agency.

147Zhang, D. H. (2018), “The Concept of ‘Community of Common Destiny’ in China’s Diplomacy: Meaning, Motives and Implications”, Asia & the Pacific Policy Studies, 5: 2, pp. 196-207.

148Zhang, J. and Han, Y. (2013), “Testing the rhetoric of China’s soft power campaign: a case analysis of its strategic ambiguity in the Six Party Talks over North Korea’s nuclear program”, Asian Journal of Communication, 23: 2, pp. 191-208.

149Zhu, Z. Q. (2010), China’s New Diplomacy: Rationale, Strategies and Significance, Farnham: Ashgate.

Notes

1 The authors have used David Cowhig’s (2017) translations for the partnership types.

2 Several sources were used to compare the four factors described above with partnership levels. Data on military interaction originates from the dataset compiled by Allen et al. (2017). For trade data, this study uses the Obersvatory of Economic Complexity (OEC) at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (OEC, 2018) and the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China’s “Connectivity Index” (ICBC, 2017). Information on bilateral projects are from multiple sources, some of which are cited in this synopsis. Partnership information is from China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA, 2018) and the Hong Kong based newspaper Wenwei Po (2015).

To cite this article

About: Peter Braga

Peter Braga is a PhD Candidate at the UCL School of Slavonic and East European Studies. Peter’s publications have been featured in the Journal of Belarusian Studies and the forthcoming edited volume Socialism, Capitalism and Alternatives: Area Stud-ies and Global Theories published by UCL Press. His book, China’s New Silk Road, Central Asia, and the Gateway to Europe, co-authored with Dr Kaneshko Sangar, is forthcoming 2020 via Routledge (Taylor & Francis Group). Peter researches authori-tarian persistence, China-East Europe relations, and emerging powers. Contact him at peter.braga.15@ucl.ac.uk

About: Kaneshko Sangar

Dr Kaneshko Sangar is a Russia foreign policy specialist and a new Silk Road expert. Contact him at k.sangar.12@ucl.ac.uk