- Accueil

- 2/2021 - Special issue Western Balkans, European U...

- Role of Political Actors in the EU Integration Process: Cases of Kosovo, North Macedonia and Albania

Visualisation(s): 1962 (34 ULiège)

Téléchargement(s): 0 (0 ULiège)

Role of Political Actors in the EU Integration Process: Cases of Kosovo, North Macedonia and Albania

Abstract

Political actors bear a pivotal importance in advancing/hindering the European Union (EU) integration process in the Western Balkans (Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Serbia). All countries of the Western Balkans have marked similarities but also significant differences in relation to their dynamics and developmental outlook. In order to make the article more concrete, we focus the attention on Kosovo, North Macedonia and Albania. The article uses a comparative method to pit against each other indicators pointing to similarities and differences among these countries, in the context of finding the factors of progressing and hindering towards the EU integration for the three countries. The factors in focus are: ruling majority-opposition and political parties, international actors, civil society, the media, public perceptions, and ethnic and nationalistic divisions (a specific factor in North Macedonia and Kosovo). The analyze show that there has been improvement is some aspects. The political parties, the ruling majority and opposition, give both tendencies towards the more inclusive political situation and pragmatist one of their interests fulfilling. International actors, civil society and the media show contribution to the EU integration. For the last factor, results indicate that in North Macedonia ethnicity is a major cause behind political conflicts, with a clear impact on the EU integration process. Kosovo is to be located somewhere in the middle, as interethnic relations play a role, but also internal strife is significant in terms of defining the forcefield between the different political and ethnic actors.

Table des matières

Introduction

1The three neighbor countries, Kosovo, North Macedonia and Albania, as part of the Western Balkans, since the fall of communism cope with explicit challenges from centralized to democratic political process. In order to enter the European Union (EU), they also need to fulfill politically and technically the EU Copenhagen criterions (political, economic, and acquis communautaire). The stages process is dependent on each of the country’s own progress (De Munter, 2020). The progress of country consolidation and recommendations for factors to be corrected are every year delivered by the European Commission on its progress reports. Meanwhile, the EU’s relations with the Western Balkan countries take place within a special framework known as the Stabilization and Association Process (SAP). The SAP has three aims: stabilizing the countries politically and encouraging their swift transition to a market economy, promoting regional cooperation and eventual membership of the EU (European Commission, 2020). If we consider the EU integration stages of the three states on focus, it is noticed that they have different timetable of the EU integration process. Albania and North Macedonia are candidate countries (respectively since 2014 and 2005), sharing a nine-year period difference between them from the starting point of this status. Kosovo began the integration process in 2014, eleven and fourteen years after the latest two. Thus for, Kosovo, as an independent state since 2008, could be considered to have a separate tendency of development compared to the other two. Although, in this article we will see that there are many similarities in the way the main political actors act, especially how the political parties act in their internal country politics.

2Some specific characteristics of the Western Balkans are their communist past, border conflicts, post-war period of state-building process, leadership with an authoritarian tendency, the government disputes between the ruling majority-opposition relations, bilateral disagreement between the neighbor states, ethnic divisions and nationalistic accounts. Considering these variables, the Western Balkan countries confront a new European reality of state-building in terms of democratic development. Concentrating the comparison of the main affecting political indicators in only three Western Balkan states that share some common outlines, helps in a specific oriented analyze and qualitative results. Therefore, the focus of this article is the analyze and comparison of the main political actors’ contribution in the EU accession progress for Kosovo, North Macedonia and Albania, in the period from 2009 to 2019.

3From the methodological point of view, this article is an attempt to map the contribution to the European integration process of the main political actors. More precisely, the research question is: what is the role of the political actors in the EU integration process, in the cases of Kosovo, North Macedonia and Albania? To answer the research question is applied a comparative perspective due to their peculiarities. This method is used to confront similar indicators, pointing to similarities and differences among these countries. The dependent variable is therefore the EU integration process. The analyze has the dimension of a case study, where the independent factors are cross-compared in their impact on enlargement. Our independent variables in this research are the political parties, civil society actors, international actors, the ruling majority-opposition relations, the media, ethnic divisions and nationalistic narratives. Furthermore, for each of the actors the analyze is divided in two main lines, in the way of positive and negative influence towards the EU integration. This article’s goal is to single out success stories, achievements, and to describe the motives and drivers of progress and causes behind failures. More specifically, each of our target countries presents a highly specific context in relation to the actors involved in the EU integration process. Firstly, the data used for this article are mainly of two forms: the official data, official reports, countries analyze, etc. Secondly, a crucial role in the comparison is the usage of statistical data from surveys, Balkan Public Barometer mapping the public perception of political actors and also data from the CHESdata survey focusing on statistical data of the three countries’ political parties’ attitude over the European integration.

4The three states present interesting elements in terms of political parties and other political actors. Since political parties are the bases of government and opposition of a country, their nature, as also their leaders, are related to the government behavior towards the EU progress. In this regard, the first part of this article examines in detail the political parties’ role in this process. Specifically, their attitude compatibility towards the progress in the checks and balances reforms and governance, central and local administration, legislation reforms, fighting against corruption and getting better neighborhood relationships, are factors that will be analyzed in this section. In order to complete the framework of the research question, the article further analyzes other actors, such as international actors, the media, civil society, ethnic and nationalistic divisions (a specific factor in North Macedonia and Kosovo), and the citizen, as part of a fundamental role in the integration process, is going to be considered in analyses.

The ruling majority-opposition political parties’1 role

5The first actor to be analyzed is the role of the countries’ main political parties. Primary, we have to remark that in all three states there have been positive progress on making the political atmosphere more inclusive for the opposition. Furthermore, data will show the progression on the check and balance situation of the governance. Therefore, from this point of view, the political arena results to be more open on fulfilling the EU criterion of integration.

6Specifically, since 2001 in North Macedonia the most important development is the deep political crisis overcome. The application of the “urgent reform priorities”, “in the fields of rule of law and fundamental rights, depoliticization of the public administration, freedom of expression and electoral reform” (European Commission, 2015) gave the government a positive motivation for the parliament and government functioning. In the last period, particularly from 2017, opposition parties took important leading positions. This positive factor led consequently to a better practically application of independence from the juridical institutions and controlling bodies. A good example in this context is solutioning the Wiretapping Affair of 2015. The committee of inquiry, based on the June 2, 2015, agreement for the solution of the political crisis, worked in order to identify political responsibility by looking into the conversations that have been taped (Pajaziti, 2015). Likewise, in Albania and Kosovo there have been a progress in terms of political parties’ attitudes and central government. In Albania, the Public Administration Reform Strategy was adopted, resulting in a better depoliticization of the state professional officials from the political parties and political majority. As per the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE) rapporteurs “The political environment, the cooperation between ruling majority and opposition, as well as electoral reform in line with OSCE/ODIHR2 and Venice Commission recommendations, were main topics during the discussions with all political forces” (Council of Europe Office in Tirana, 2018). One of the most important action of the Albanian Assembly is the unanimous approval and adoption of the legal reform and the constitutional amendments. Furthermore, Albania has made progress on launching the vetting process procedure of magistrates in 2014, fighting organized crime as also the cultivation and traffic of cannabis (in the line of fulfilling the priority 2 and 4 of the European Commission).

7On the other hand, in Kosovo, the government is devoted and promised to accomplish the European Reform Agenda (ERA) (Republic of Kosovo, 2016). Even though the slow progress, likewise in Albania, there have been good efforts on the “fight against corruption, pointing specifically towards the lack of transparency and accountability of political parties, an issue civil society groups frequently denounced” (Martínez et al., 2018, p. 13). Apart from the own country governance and political actors, the EU has a decisive role in this development, by pressuring the Kosovar institutions. An illustrative example was on March 2018 with the ratification of the border demarcation with Montenegro. The ratification took place, but there was strong resistance from opposition parties such as Self-determination Movement (LVV) and a significant number of the citizens of Kosovo (Bytyçi, 2018).

8Another key element of positive similarities is the tendency of election administration, both municipal and parliamentary. All three countries have made positive development on that regard. Consequently, the election process and results show signs of development towards the European criterions of inclusions and transparency. Differently from the former period of elections in Albania, the European Commission reports that “the 2017 parliamentary elections were held in an orderly manner and its results were accepted by all parties. The May 2017 cross-party political agreement resulted in the opposition’s participation in the election and a less aggressive electoral campaign” (European Commission, 2018a, p. 7). Meanwhile in “North Macedonia significant improvements had been made to the electoral legislation and more confidence in the voter’s list, addressing most of the OSCE/ODIHR and Venice Commission recommendations” (European Commission, 2018b, p. 5). Likewise, Kosovo has also made some progress on both local and central election by better administrating them. Thus, in all three countries progressive development is shown in the election point of view towards the EU integration criterions fulfillment.

9A final positive argument is the ending of parliament boycott. North Macedonia and Albania have experienced this situation in 2016 and 2017. In Albania (2017), the opposition parties hindered the political life by blocking the parliament activities, while political parties also prolonged the crisis in North Macedonia (2001-2016). Political parties’ agreements were ensured in both states from the EU interventions. In Albania, the Prime Minister Edi Rama and the leader of the Democratic Party of Albania (PD) Lulzim Basha overcome the parliament boycott and release the normal political and government activities. In North Macedonia with the Pržino Agreement, the opposition party Social Democratic Union of North Macedonia (SDSM) return the parliament. In both countries, the arrangements also included that some of the key position of the government or committees to be chaired by the political opposition parties. Such positions were ministers and parliament chair. In Albanian case the political parties went beyond this step, by establishing a technical government composed by ten ministries from the position party (Socialist Party of Albania (PS)) and eleven ministries from the opposition parties of PD and Social Movement for Integration (LSI). This was the first time in Albanian politics that a government is composed more from opposition parties than the actual government political party (Krasniqi, pp. 7-8).

10Hence, all three countries have made good progress in the checks and balances reforms and governance, from central, local, administration, legislation, fighting against corruption and getting better neighborhood relationships.

11Apart from the above positive role of the political parties and government/opposition in the EU integration, next are analyzed the delaying ones. The most two obvious factors for Kosovo, North Macedonia and Albania are the tendency for strong control of the majority leader and the strong polarization of political parties. Nevertheless, there is a difference between North Macedonia and the other two countries. In Kosovo and Albania, the leader control is more moderate than in North Macedonia, where the former Prime Minister Nikola Gruevski, showed mostly an authoritarian control (Bieber, 2018). This results in a difficult process of governance and further democratization of the countries, hence hindering the EU integration. The situation is deep-rooted in a long time period for these parties in power. For example, in Albania, the PS is in power from 2013, with Edi Rama as Prime Minister. Similarly, in North Macedonia, the leader of the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization-Democratic Party for Macedonian National Unity (VMRO-DPMNE) Nikola Gruevski governed for ten years from 2006 to 2016. In North Macedonia’s politics there is a strong rhetoric aiming against the ethnic Albanians. Linked to this problematic of the governance, we also notice other challenging factors such as corruption, asylum seeker (especially in Albania) and government approach to control the parliament. The polarization of political parties reflects and contributes in a difficult work for the governments of the countries, difficulties in the government formation (North Macedonia in 2017) and problematic tendency of internal parties’ fragmentation (mainly in Albania and Kosovo). Consequently, these hampering aspects somehow brought difficulties to the governments functioning, executing improvements and problems solving. For example, in 2017, in Kosovo this situation brought a weak political coalition that was dependent on the minority’s parties (Martínez et al., 2018, p. 3). Kosovo reflects an interesting case, where the political party LVV performs in some interior politics critics on the EU integration, due to its nationalistic tendency politics (Bieber, 2015, p. 311), and the desire to be politically unified with Albania in one state. Nonetheless, this party is in favor of the European integration, as the best road to the Kosovo’s development (Feilcke, 2019). These arguments of internal political polarization and power centralization tendency from the party’s leadership also convey in the obstructive behaviors of the political parliamentary opposition. Additionally, this political situation impacts the citizen3 to suffer from the overpowering control of the party’s leadership. In overall, these arguments point to a slowdown progress of the EU integration process.

12Since political parties and their leaders result to be the most decisive political actors in the EU integration process, as also in the domestic politics of the country, this section analyzes statistically three factors that are considered politically determinant: the relative salience of European integration in the parties public stance in 2014; the position of the parties leadership in 2014 on fulfilling the good governance requirements of EU membership (administrative transparency, accountability, civil service reform and judicial reform); the overall orientation of the party leadership towards membership of the EU in 2014. The statistics are part of the CHES candidate survey of 2014 (Table 1).

13The descriptive data confirm the above tendency of the political parties and leaders of the three Western Balkan countries. Therefore, it is not a surprise that political parties of North Macedonia show the highest level out of these three Western Balkan states of opposing the overall orientation of the party leadership towards membership of the EU: VMRO-DPMNE 50.10 % (opposes and somewhat opposes). Almost half of the party leadership has a tendency to actually obstruct the EU politics. The other parties in North Macedonia also show opposition but in moderate levels, between 20-25 %: the Democratic Party of Albanians (PDSH) 22.7 %, the Democratic Union for Integration (BDI) 25 % and the Citizen Option for Macedonia (GROM) 22.6 %. As expected, in Kosovo only two parties have moderate levels of opposition, the LVV 21.4 % and Serb List (SL) 25 % (mostly opposition in some politics). The other significant parties tend to 100 % of favoring the EU, such as the Alliance for the Future of Kosovo (AAK), Democratic League of Kosovo (LDK), New Kosovo Alliance (AKR), Democratic Party of Kosovo (PDK). Albania tends mostly to have a leader that supports the EU integration. The actual government party of PS, shows the tendency of 100 % pro-EU integration from its leader. There are a few small parties, mostly minority parties and national politics program parties, that lightly oppose the EU integration support, such as the Unity for Human Rights Party (PBDNJ) 13.40 % and the Republican Party of Albania (PR) 15.40 %. The results also show a 20 % of the today main opposition PD party leadership orientation in opposing the EU integration. This result could probably be explained with this time polarization and opposition status, by minimal chances in contributing to the Albanian governance.

14According to salience of the political parties in the European integration public stance in North Macedonia, Albanians and North Macedonians show more evidence of positive trend. The position of the party leadership in 2014 on fulfilling the good governance requirements of EU membership is generally in line with the position of their party towards EU integration. The most notable case is VMRO-DPMNE party, which in all three variables opposes with 67 % the fulfilling of good governance requirements of EU membership (administrative transparency, accountability, civil service reform and judicial reform). The other parties show a constant trend on what they declare and actually act. In Albania, the political parties and leaders of PS, PR, Christian Democratic Party of Albania (PKDSH) and LSI and mostly are stable in their position to the EU via their public salience, fulfilling the good governance requirements of EU membership. The only party that somehow contradicts in this set of data is PD. Publicly its salience is declared to be of great importance to the EU integration at the level of 94 %, while at the level of 20 % it opposes the fulfilling the good governance requirements of EU membership (administrative transparency, accountability, civil service reform and judicial reform as also the overall party leadership oriented towards the EU). Meanwhile in the Kosovo’s data, we observe another issue. Generally, in the majority of the political parties in Kosovo the public stance is more opposing than the leadership of that party towards membership. The exception in this case is made from the LDK, which shows a stability in its EU integration importance of fully in favor. Parties like AAK, AKR and Social Democratic Initiative (NSD), moderately show public posture towards the non-importance of EU integration. Like in North Macedonia, in Kosovo there is also a political party, SL, that demonstrates an almost extreme public stance against the EU integration of 70 % compared to that of 25 % of the leadership and 43 % of the EU requirement of good governance fulfillment.

15In conclusion, generally political parties and their leadership do show positive public attitude towards the EU integration. Whereas if we go deeper in the analyze, we find different behaviors between each country and between the countries at the comparison level. Political parties tend to be pragmatic and fulfill their own interest, rather than the country and citizen interest.

Table 1. Political parties’ attitude toward the EU integration

|

Indicator |

Relative salience of European integration in the party’s public stance in 2014 |

Position of the party leadership in 2014 on fulfilling the good governance requirements of EU membership (administrative transparency, accountability, civil service reform and judicial reform) |

Overall orientation of the party leadership towards membership of the EU in 2014 |

||||

|

Country |

Party name |

European integration is of no importance |

European integration is of importance |

Opposes |

In Favor |

Opposes |

In Favor |

|

Kosovo |

AAK |

7.70 % |

84.70 % |

15.40 % |

77.00 % |

0.00 % |

92.90 % |

|

AKR |

15.40 % |

69.30 % |

0.00 % |

100.10 % |

0.00 % |

100.00 % |

|

|

LDK |

0.00 % |

92.40 % |

15.40 % |

77.00 % |

0.00 % |

100.10 % |

|

|

LVV |

23.10 % |

46.20 % |

8.30 % |

91.70 % |

21.40 % |

71.50 % |

|

|

NSD |

15.40 % |

46.20 % |

9.10 % |

90.90 % |

0.00 % |

100.00 % |

|

|

PDK |

0.00 % |

92.30 % |

30.80 % |

69.30 % |

0.00 % |

100.00 % |

|

|

SL |

69.30 % |

7.70 % |

42.90 % |

28.60 % |

25.00 % |

24.90 % |

|

|

North Macedonia4 |

PDSH |

37.50 % |

45.90 % |

36.30 % |

49.90 % |

22.70 % |

45.50 % |

|

BDI |

20.90 % |

58.30 % |

54.20 % |

37.50 % |

25.00 % |

62.50 % |

|

|

GROM |

25.10 % |

41.60 % |

19.00 % |

52.40 % |

22.60 % |

59.00 % |

|

|

RDK |

20.90 % |

58.30 % |

15.80 % |

73.70 % |

20.00 % |

65.00 % |

|

|

SDSM |

4.20 % |

79.20 % |

12.50 % |

79.20 % |

8.70 % |

86.90 % |

|

|

VMRO-DPMNE |

54.20 % |

37.50 % |

66.70 % |

24.90 % |

50.10 % |

50.10 % |

|

|

Albania |

LSI |

6.70 % |

93.40 % |

6.70 % |

93.40 % |

6.70 % |

93.40 % |

|

PBDNJ |

6.70 % |

73.40 % |

7.10 % |

92.90 % |

13.40 % |

73.40 % |

|

|

PD |

0.00 % |

93.30 % |

20.00 % |

80.00 % |

20.00 % |

80.00 % |

|

|

PDIU |

20.00 % |

66.70 % |

7.70 % |

84.60 % |

0.00 % |

100.00 % |

|

|

PKDSH |

14.20 % |

57.10 % |

9.10 % |

81.90 % |

9.10 % |

72.80 % |

|

|

PR |

13.40 % |

80.00 % |

15.40 % |

69.30 % |

15.40 % |

84.70 % |

|

|

PS |

6.70 % |

93.40 % |

6.70 % |

93.30 % |

6.70 % |

93.30 % |

|

16Source: CHESDATA, 2014.

The civil society

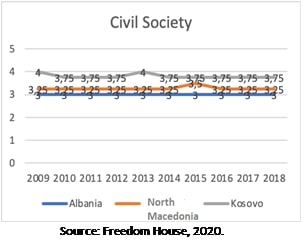

17The second factor to be analyzed is the role of the civil society. The Freedom House indicator’s measurement5 shows that in each of the three countries the tendency stays in almost the same figures in nine years (Freedom House, 2020). More specifically, Albania has the best result, at the rate of 3 points, North Macedonia 3.25 points and Kosovo 3.75 points. We should note that compared to the media, civil society plays a more important role towards EU integration, thus deducting that the media is politicized because of the political parties.

18The civil society, compared to the other actors, shows almost more similarities in its action. Therefore, in Albania, the 2014 Law on public consultation lading down the procedural norms for transparency and public participation in decision-making is in line with European standards (European Commission, 2018a, p. 11). A very good example of public participation is the student protest, by the end of 2018-beginning of 2019 (Top Channel, 2018). This fact proved the functioning of the civil society.

19As per Kosovo, Freedom House states for progress in the cooperation between government and civil society. The government showed a higher disposition to engage with civil society and involve it in political processes. On the other way, the regulation on minimum standards for civil society consultation, approved in 2016, has been implemented in a proper manner, and an environment of communication akin to that existing at the Assembly is starting to develop. Civil society organizations have been increasingly active this year in a number of fields, including European integration (Martínez et al., 2018, p. 8). Similarly, in North Macedonia some progress towards the integration of the civil society dialoguing with the government is noticed, contributing therefore to the democratization of the country. An example is the adoption of “the Strategy for cooperation with and development of the civil society, as well as the Action Plan 2018-2020” (Balkan Civil Society Development Network, 2018). The European Commission confirms the above by stating that the “Civil society and other stakeholders are increasingly being involved in the policy-making and legislative processes and continued to play a constructive role in supporting democratic processes and ensuring greater checks and balances” (European Commission, 2018b, pp. 4-5).

20Even though in all three states this progress of civil society is hindered in some stance by different factors. In Albania, the organization of the civil society is mostly not institutionalized and the “foreign donor support constitutes the main source of financial income” (Partners Albania for Change and Development, 2017, p. 14). In Kosovo and North Macedonia, the ethnocentric groups prevent more inclusion and the democratic development of the country, therefore hindering the EU integration. From the point of view of this factor, Albania stands in a better place than the other two in the road towards the EU. We can thus also confirm that till the present analyze, mostly the same hindering factors rotate in the delaying issues of these countries.

The international actors

21The third factor to be analyzed is the role of the international actors. These actors play a significant role in stabilizing the democratic, economic and juridical area of the three countries, as also stabilizing the intern area of the political parties and between the parties themselves. The United States (US) and the EU are both actors that positively contribute towards the EU integration of the three states. It consists on contributing to a more democratic society by consulting the legal and political countries’ topics. In Albania, for example, the main two parties’ leaders Lulzim Basha (PD) and Edi Rama (PS) reached an agreement in May 2017 (Bota Sot, 2019). Meanwhile in Kosovo, an obvious actor influencing the country politics is the US. An example: “the United States has in the past engineered coalitions to prevent the Self-Determination Movement from taking office” (BiEPAG, 2017, p. 7). However, the US also serves as a national protector of the Republic of Kosovo. Furthermore, the EU assisted Kosovo to reach agreements with Serbia to normalize their bilateral relations (Technical and Political Dialogue Agreements). Apart from the positive achievements in these years, yet there is a “dialogues lack of transparency, and this might jeopardize the achievements reached through this process” (Beha, 2015, p. 102), impacting thus on delaying the EU integration process. North Macedonia, on the other way, differs slightly from Albania and Kosovo, because of less influence from the US into the intern politics than the other two. Nevertheless, the EU and the US did mediate in some areas of the political parties and politics in general. The best example is the Pržino Agreement in North Macedonia, with the intervention and direction of the EU. This pact stabilized the prolonged conflicts with Bulgaria and Greece, by reaching an agreement in June 2018 to rename the country the Republic of North Macedonia (Harris, 2019). In overall, this is the most obvious positive progress in North Macedonia.

22As per the hindering factors of EU integration in the three states, they are generally linked to the same positive ones analyzed in the preceding paragraph. The most negative influences towards the hindering to the EU integration do concern North Macedonia and Kosovo, while Albania stands in a more sustainable and calm position. As it is mentioned already in this article, North Macedonia faced for a long time its name dispute with Greece, which was a constant obstruction for its integration. Kosovo faces continuous tensions mostly in the north of its territory, with the Serbian political parties, like the LS. This last one in 2016 “proclaimed it would boycott the work of parliament and government. These political and social problems demonstrate how difficult the road still is toward developing a functioning civil society, reconciliation between Kosovo’s different ethnic groups and the country’s full integration into international political structures” (Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2018, p. 4).

23EU accession consists on complex long-term administrative and bureaucratic procedures, favoring the projection of influence of the emerging powers like Russia, Turkey and China in the Western Balkans. Generally, these emerging powers stand the point of view that these countries have other alternatives rather than the EU and NATO (Hänsel and Feyerabend, 2018). Turkey acts in a soft power base, such as investments in economy, culture, TV series, opening of Turkish colleges, restoration of mosques, etc. Russia, on the other hand, is not in favor of NATO and EU enlargement by promoting its political, economic and traditional ties with certain countries (like Serbia) in the region, presenting itself to them as a closer ally than the EU. Meanwhile, China “tries to compete with the EU through its autocratic model and its non-democratic principles” (Lika, 2020). However, there are a lot of critics about the Russian, Turkish, and Chinese influence in the Western Balkans (Lika, 2020; Rrustemi et al., 2019). Despite the long-term procedure of European integration and the increasing tendency of influences from the emerging powers, the EU remains a key political and economic partner for Kosovo, North Macedonia and Albania.

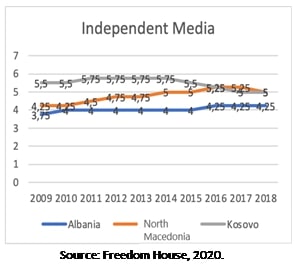

The media

24The fourth factor to be analyzed is the media. “Media freedom represents without any doubt one of the most difficult challenges as the country aspires to be democratic and transparent, as well as to respect human rights and fundamental freedoms” (Hoti and Gërguri 2015, p. 29). As in the case of civil society, also for the media, there are basically similarities between the three countries. All three states show a more progressive environment towards the media freedom. In this context, online media has its own importance, considering its large spread into the society. Nevertheless, Albania and North Macedonia are moderately prepared in the field of electronic communications and the information society (European Commission, 2018a; European Commission, 2018b) whereas Kosovo has a lower level of preparation in this area (European Commission, 2018c, p. 73). Although, in general the media in Kosovo is getting more independent than the previous period (5.5 in 2009 to 5 point in 2018) (Freedom House, 2020). Differently, Albania and North Macedonia between 2015-2018 have been slightly deteriorating in the media independence, 4.25 point and the second in the margin of 5-5.25 points. In overall, if we reflect on the media indicators, such as freedom of expression, critical media and media reporting, we can assert that the three countries are in a somewhat good position in being a linkage between the citizens and the EU integraton. In this regard, each country has made legislative media change. For example, in Albania, the Audio Visive Media Authority (AMA) approved the strategic action plan 2017-2019. Furthermore, “the condition of North Macedonia’s independent media improved slightly in 2017, reflecting positive developments in the credibility of media reporting as a result of the change in power at the central level” (Bliznakovski, 2018). In Kosovo, the journalists have grown their professional abilities to inspect proofs and actualities. Having this in mind, the Kosovar government is trying to accelerate the integration process by supporting the idea of free and transparent media as a precondition to EU membership. Such an objective has become an obligatory part of many documents deriving from the Kosovar Constitution as well as other plans and strategies like the National Strategy for European integration ‘Kosovo 2020’ (Hoti and Gërguri 2015, p. 29). This last argument could be one of the explanations of a better performance of the media in Kosovo than in Albania and North Macedonia, which are already candidate countries.

25Besides the positive factors of the media, this sector also challenges delaying ones. The media of North Macedonia and Albania show some characteristics of dependency from the political parties. In North Macedonia, Alfa and Nova TV are more in favor of VMRO-DPMNE; the TV such as ALSAT-M and 24 TV are less polarized (Bliznakovski, 2018). Also, in Albania, some private media show tendency of dependency in their news towards the political parties and mainly for the most important ones, PD and PS. Furthermore, these Albanian media has the tendency towards the ground creation of an opinion-based journalism and fake news (Zguri, 2017, p. 58). In Kosovo, the European Commission invite the state authorities to take further steps “on the regulation of media ownership and transparency” (European Commission, 2018c, p. 22). In Kosovo and North Macedonia differently from Albania, the media problematics are also connected to the ethnic, linguistic and nationalist conflicts, thus reflecting these issues in the media sector. The European Commission often advice that the government should take further political and legal provisions in this direction (European Commission, 2018a, p. 7).

The ethnic divisions and nationalistic narratives

26The fifth actors to be analyzed are the ethnic divisions and nationalistic narratives. In two out of three countries, ethnic divisions and nationalistic narratives effect the political stability of countries. In the case of Albania this variable is not an influencer for the political actions. Albania is best known for ethnic and religion tolerance (UNDP, 2018, p. 25). Therefore, political parties do not take into consideration in their political actions neither of them. Furthermore, there has been progress towards human rights, policies of anti-discrimination, Roma rights (priority 5): the legal framework for the protection of human rights is broadly in line with European standards, national strategy on social protection for 2015-2020 is under implementation (European Commission, 2018a). Albania has ratified most international human rights conventions. “The overall legislative environment is conducive to the exercise of freedom of religion and progress was made in strengthening the independence of the regulatory authority and public broadcaster” (European Commission, 2018a, p. 78). Despite this positive situation, further enforcement for human rights have to continue (European Commission, 2018b) and also “the government should step up its efforts to ensure there is a comprehensive plan for building up the capacity of all line ministries and local governments to implement the actions in the document” (European Commission, 2018b, p. 78).

27Differently to Albania, Kosovo and North Macedonia have still problems that concern interethnic relations (Demjaha and Peci, 2014, p. 4), However, there has been some progress in this area in Kosovo, “such as the application of the ethnic quotas in the relevant administrative jurisdiction, at the local level, at the government level, twenty seats in the Parliament (one sixth of the Assembly), as well as a minimum of ministerial positions” (Martínez et al., 2018, pp. 5-6). Otherwise, since 2011, the EU has been facilitating the dialogue on the normalization of bilateral relations between Kosovo and Serbia (Visoka and Doyle, 2016). “Still, the dialogue has delivered far less than expected. Conflicting interpretations and contradictory narratives of Kosovo and Serbia exacerbated differences” (Demjaha, 2018, p. 22). But, official reciprocal recognition between these two states is important in order to move forward on the path of European integration (Hajrullahu, 2019).

28The adoption of the double linguistic law on 11 January 2018 (Marusic, 2018) and the improvement of the interethnic relations are the most important developments in North Macedonia. According to 2002 census, the Albanians in this country make one fourth of the population (The State Statistical Office, 2002, p. 34). This population does not feel represented in the North Macedonia’s institutions. On this purpose, the Ohrid Framework Agreement implementation (Ohrid Framework Agreement, 2001) “paved the way for major political reforms that improved the rights of the Albanians in North Macedonia” (Krasniqi, 2011, p. 22). However, “the Ohrid Agreement has only been partly successful in addressing the root causes of the conflict” (Bieber, 2005, pp. 89-107).

29Apart from the positive actions, these two countries still have challenges that hinder the EU integration process. Political actors themselves utilize these problems on their pragmatist interest. Specifically, the main challenge of Kosovo is the integration of the Serbian minority in the Kosovar politics. North Macedonia is the country that has the most serious consequences on this point of view, because of the long-time tensions between ethnic Albanians and North Macedonians. This inside hindering conflict is extended in time. One of the culminations of this conflict was in 2016, when the government did not form because one of the main political party in North Macedonia VMRO-DPMNE did not accept officially the Albanian language.

30Given the importance of these indicators in Kosovo and North Macedonia, in Table 2, we illustrate the political parties’ attitudes on ethnicity and nationalism. As already deliberated, these two states have a common variable that plays an active/important hindering role in EU integration process. North Macedonia, as is mentioned earlier in the analyze of this article, brings up in its political parties the problems of ethnicity and nationalism. The empiric data confirm this point of view. PDSH, BDI are almost (+90 %) compatible and fully in support of more rights for ethnic groups and nationalistic view of the society. Whereas, VMRO-DPMNE support nationalism (+90 %), and has a low rate of support for ethnic rights (14.3 %). In Kosovo’s data the only party that does oppose the ethnic rights for ethnic minorities at a high level is LVV 67 % (CHESDATA, 2014). The other parties result more moderate, for example NSD follows with 25 %. AKR, LDK and PDK are parties that mostly support cosmopolitan views of the society (linking political party’s politicization and inside political interest); these parties also support ethnic rights of minorities in Kosovo, while SL’s result in this area is 100 % of support (CHESDATA, 2014).

Table 2. Kosovo and North Macedonia political parties’ ethnic minorities and nationalism position

|

Indicator |

Position towards nationalism |

Position towards ethnic minorities |

|||

|

Country |

Party name |

Promotes cosmopolitan rather than nationalist conceptions of society |

Promotes nationalist rather than cosmopolitan conceptions of society |

Opposes more rights for ethnic minorities |

Supports more rights for ethnic minorities |

|

North Macedonia |

PDSH |

4.30 % |

95.60 % |

4.80 % |

95.30 % |

|

BDI |

4.30 % |

95.70 % |

4.80 % |

95.30 % |

|

|

GROM |

38.90 % |

27.90 % |

13.40 % |

46.70 % |

|

|

RDK |

11.20 % |

72.30 % |

0.00 % |

100.00 % |

|

|

SDSM |

52.10 % |

13.00 % |

23.80 % |

47.70 % |

|

|

VMRO-DPMNE |

0.00 % |

91.20 % |

57.10 % |

14.30 % |

|

|

Kosovo |

AAK |

25.00 % |

0.00 % |

16.60 % |

41.70 % |

|

AKR |

81.90 % |

0.00 % |

9.10 % |

63.70 % |

|

|

LDK |

46.20 % |

0.00 % |

7.70 % |

53.90 % |

|

|

LVV |

7.70 % |

92.40 % |

66.80 % |

25.00 % |

|

|

NSD |

11.10 % |

11.10 % |

25.00 % |

41.60 % |

|

|

PDK |

46.20 % |

0.00 % |

7.70 % |

69.30 % |

|

|

SL |

0.00 % |

91.60 % |

0.00 % |

100.00 % |

|

31Source: CHESDATA, 2014.

32An additional statistical correlation test was pursued onto Kosovo, Albania and North Macedonia data of CHES 2014, to confirm the so far results (Table 3). Basically, the correlations search for the relationship between four variables: “Overall orientation of the party leadership towards membership of the EU in 2014” with “relative salience of European integration in the party’s public stance in 2014” with “position towards ethnic minorities” and with “position towards nationalism” (CHESDATA, 2014). Results show that the parties (leaders) in North Macedonia who, in overall, orient the party leadership towards membership of the EU, have the tendency to support more rights for ethnic minorities (44 %) and promote cosmopolitan rather than nationalist conceptions of the society (28 %). This cosmopolitan promotion also results to be part of the Kosovo’s parties (except LVV and SL). We could thus confirm that ethnicity and nationalism is of great importance in the political parties’ agendas, discussions, and problems occurring mainly in North Macedonia. We can assert that these variables indirectly constitute a hindering component of the EU integration delay for North Macedonia and Kosovo. Regarding to Albania, the CHES data statistical analyze confirms the results of the political parties-opposition section. Political parties and the government in Albania affirm the orientation towards the EU integration, although the public stance (56 %) is a bit lower than in Kosovo (70 %) and North Macedonia (73.5 %). This average percentage result for Albania could be linked with just a momentary factor of governance transition 2013-2014, from PD to PS, since the overall analyses of Albanian leadership presents a high level of public stance in entering the EU.

Table 3. Correlations: overall orientation of the party leadership towards membership of the EU in 2014

* relative salience of European integration in the party’s public stance in 2014

* position towards ethnic minorities

* position towards nationalism

|

|

|

Membership Kosovo |

Membership Albania |

Membership North Macedonia |

|

EU salience |

Pearson Correlation |

.700** |

.559** |

.735** |

|

Sig. (2-tailed) |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

|

N * |

87 |

97 |

135 |

|

|

Ethnic minorities |

Pearson Correlation |

-0.154 |

-0.155 |

-.280** |

|

Sig. (2-tailed) |

0.173 |

0.159 |

0.003 |

|

|

N* |

80 |

84 |

110 |

|

|

Nationalism |

Pearson Correlation |

-.446** |

0.016 |

-.439** |

|

Sig. (2-tailed) |

0 |

0.883 |

0 |

|

|

N* |

82 |

86 |

123 |

|

|

** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed). * Number of respondents cross-tabulated. Source: CHESDATA, 2014. |

|

|||

The citizen role

33The last factor in analyze is the citizen. Citizens are a vital base for the EU integration process. In terms of political actors, they set the ground from which emerge the political parties, civil society, and the media. Hence, their perceptions of desiring the EU integration must considered. The below analyzed data is taken from the Balkan Public Barometer for the period 2015-2018. The most central problems facing the entire South East Europe (SEE) as per the Balkan Barometer are the economic situation, political disputes, unemployment and corruption (Balkan Public Barometer 2014, 2020). Consequently, these issues converge in the EU priorities and restriction for the three countries to the integration process. Specifically, the economic situation in North Macedonia and Albania from the citizens’ perception is in decline from 2015 to 2018. For North Macedonia is -14 % decline, while for Albania is -25 % decline. These results could be possibly linked with reforms and intervention in the economic sector from the EU. Kosovar perception instead shows an increase of economic problems at the rate of +14 %. This could be explained by its not yet getting candidate status. On the other hand, surprisingly, regarding the corruption level and political dispute, Kosovo shows a decline of -6 % and -5 % on its perception from 2017 to 2018. These factors result to be positive for this country. In the data below (Table 4) we will notice that probably they are not so much linked with the public perception of better relationship in the SEE region. Consequently, these two variables do confirm the hindering factors analyzed in the section of negative influences.

34Accordingly, in the Balkan Public Barometer data (Table 4), the citizens of Kosovo are the most skeptical regarding the improvement of the relationship in SEE with 48 % who agree and 34 % who disagree. In contrast, the citizens of Albania have the highest level of better relationship in SEE at the level of 62 % who agree and 26 % who disagree. In between the latter two are the perceptions of the citizens of North Macedonia at the level of 57 % who agree and 30 % who disagree. In overall, from 2015 to 2018, the public perception data in Albania and Kosovo show a slight reduction of better relations in SEE, respectively in Albania of -3 % and in Kosovo of -4 %. Differently, in North Macedonia, the public shows an increasing perception of better relationship in SEE, at the rate of +8 %. The last result could be linked with the political stabilization of the government and better political relationship with the SEE.

Table 4. Do you agree that the relations in SEE are better than 12 months ago?

|

Disagree |

Agree |

|

|

Albania |

-9 |

-3 |

|

Kosovo |

-3 |

-4 |

|

North Macedonia |

-13 |

8 |

35Source: Balkan Public Barometer for the period 2015-2018.

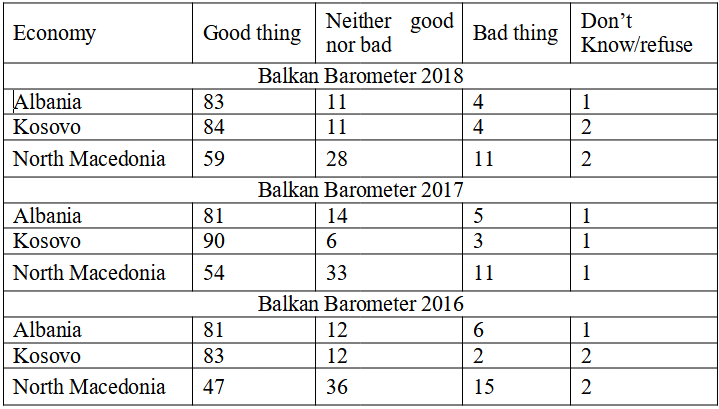

36These results are also confirmed from the public of the three countries, regarding the possibility of contribution from the regional cooperation to the political, economic or security situation of the society. Albania and Kosovo tend to agree over 80 %, and North Macedonia is in the marge of 71-82 %. North Macedonia’s public in this time period does also perceive between 11-15 % that EU membership is a bad thing, and 28-36 % is skeptic of either good or bad (Table 5). The opposite happens to Albania’s and Kosovo’s publics, showing high levels of believing in EU membership over the rate of 80 %. Therefore, the citizens of the three states have a different tendency of thinking about the EU membership. The result could be linked to the long period of candidate status. Likewise, they could also be connected to the government tendency not to apply and realize the EU directive of cooperation and problems solving.

Table 5. Do you think that EU membership would be a good thing, a bad thing, or neither good nor bad?

37Source: Balkan Public Barometer for the period 2016-2018.

38A concluding point regarding the citizens’ perception in the period 2015-2018, is their overview for the time when they expect to enter the EU. In North Macedonia 22-28 % of them confirm that will never enter the EU. The long time period of sixteen years from granting the candidate status and political and economic problems, may cause this reasoning of high-level skepticism. Otherwise, Kosovo’s public had the highest-level perception of EU accession shortly in 2020 (43 %), which is probably linked to the high level of public belief that consequently to entering the EU, problems will be solved. Seen from this angle, also the citizens of Albanian, in 2016, have the same positive perception for entering the EU, at the rate of 51 %, whereas in 2018 they show a perception of postponing the accession in 2025. Involving all the factors analyzed up to here for this country, the results are likely allied to the latest political decision, the inside unstable political climate and the party leader’s political attitude. In summary, the citizens’ perception on EU integration is affirmed to be an important factor for the political actors of Kosovo, North Macedonia and Albania to considerate in their political behavior.

Conclusion

39Despite the dissimilar length of the EU integration process of Kosovo, North Macedonia, and Albania, from the perspective of the political actors’ role, this comparative analyze emphasises their importance towards the European integration of these countries. Qualitative and quantitative data, show a significant improvement of these political factors during the integration process, even though some of them have not yet fully met the EU criterion, therefore delaying the conclusion of the integration process.

40In the three countries, international actors, civil society and the media have the most positive impact on the progress of the EU integration process. Despite the influence projection policies of emerging powers such as Russia, Turkey and China in the Western Balkans, the EU remains the crucial international actor contributing in the three countries development. Even though some critics advice that the EU needs to relief the political pressure on these Western Balkans countries in order to integrate them as soon as possible into its project, the latter is continuing its enlargement strategy based on its merit criterion. As well, there is still room for improvement in the institutionalization of civil society, the depoliticization of the media (mostly in North Macedonia and Albania) and the settlement of bilateral disputes with neighbouring countries (mostly regarding the North Macedonia and Kosovo). Despite the long duration of the process (mainly in North Macedonia), the public perception still remains positive in terms of the significance and desire for the country to be part of the EU.

41Kosovo, North Macedonia and Albania have shown a positive attitude towards implementing in their central and local governments progressive reforms such as: depoliticization of state administration employees, the fight against corruption, the improvement of relations with neighbouring countries and the justice system. A factor that has intervened in hindering this politics is the somehow strong political leadership attitude of the main political parties, hence delaying the fulfilling of the EU integration criteria.

42A specific similar factor in North Macedonia and Kosovo is the nationalistic and ethnic divisions. Among the other factors analyzed in this article, disputes based on ethnicity and nationalism can be considered as one of the factors of delaying the EU integration process for these two states. Nevertheless, considering the positive attitude of the main political actors in Kosovo and North Macedonia and the pro-EU integration desire of their citizens, we can assert that this issue is today not an obstacle for the them to join the EU.

43As a conclusion, despite the delaying issues, this article asserts that the role of the political actors, in overall towards the EU integration process is positive for Kosovo, North Macedonia and Albania.

References

44Books

45Hänsel Lars and Feyerabend Florian C. (2018), The influence of external actors in the Western Balkans. A map of geopolitical players, Sankt Augustin/Berlin: Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e. V.

46Zguri Rrapo (2017), Marrëdhëniet mes Medias dhe Politikës në Shqipёri, Tiranë: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Office.

47Chapters in edited books

48Bieber Florian (2005), “Partial Implementation, Partial Success: The Case of Macedonia”, in O’Flynn Ian and Russel David (eds.), New Challenges to Powersharing. Institutional and Social Reform in Divided Societies, London: Pluto Press, pp. 89-107.

49Demjaha Agon (2018), “The Impact of Brussels Dialogue on Kosovo’s Sovereignty”, in Phillips David L. and Peci Lulzim (eds.), Threats and challenges to Kosovo’s sovereignty, Prishtina-New York: Institute for the Study of Human Rights at Columbia University in co-operation with the Kosovar Institute for Policy Research and Development (KIPRED), pp. 11-24.

50Articles of scientific journals

51Beha Adem (2015), “Disputes over the 15-point agreement on normalization of relations between Kosovo and Serbia”, Nationalities Papers: The Journal of Nationalism and Ethnicity, vol. 43, Issue 1, pp. 102-121.

52Bieber Florian (2015), “The Serbia-Kosovo Agreements: An EU Success Story?”, Review of Central and East European Law, 40, pp. 285-319.

53Bieber Florian (2018), “The Rise (and Fall) of Balkan Stabilitocracies”, Horizons: Journal of International Relations and Sustainable Development, n° 10, pp. 176-185.

54Hajrullahu Arben (2019), “The Serbia Kosovo Dispute and the European Integration Perspective”, European Foreign Affairs Review, vol. 24, Issue 1, pp. 101-120.

55Hoti Afrim and Gërguri Dren (2015), “Media freedom – a challenge in Kosovo’s European integration process”, Uropolity, vol. 9, n° 2, pp. 29-46.

56Visoka Gёzim and Doyle John (2016), “Neo‐Functional Peace: The European Union Way of Resolving Conflicts”, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, vol. 54, n° 4, pp. 862-877.

57Reports

58Balkan Civil Society Development Network (2018), Macedonia: Government Strategy for Cooperation with and Development of Civil Society Adopted, available at: https://www.balkancsd.net/macedonia-government-strategy-for-cooperation-with-and-development-of-civil-society-adopted/ (accessed 10 December 2018).

59Balkan Public Barometer (2020), Regional Cooperation Council, Data for the period 2015-2018, available at: https://www.rcc.int/seeds/results/2/balkan-public-barometer (accessed 22 February 2021).

60BiEPAG (Balkans in Europe Policy Advisory Group) (2017), “The Crisis of Democracy in the Western Balkans. Authoritarianism and EU Stabilitocracy”, Policy Paper, available at: http://www.biepag.eu/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/BIEPAG-The-Crisis-of-Democracy-in-the-Western-Balkans.-Authoritarianism-and-EU-Stabilitocracy-web.pdf (accessed 10 February 2018).

61Bliznakovski Jovan (2018), “North Macedonia: Nations in Transit 2018”, Freedom House, available at: https://freedomhouse.org/country/north-macedonia/nations-transit/2018 (accessed 2 April 2019).

62Council of Europe Office in Tirana (2018), PACE rapporteurs: satisfaction with vetting of judges and prosecutors; further steps needed to fight high-level corruption, Strasbourg, available at: https://www.coe.int/en/web/tirana/-/pace-rapporteurs-satisfaction-with-vetting-of-judges-and-prosecutors-further-steps-needed-to-fight-high-level-corruption (accessed 12 January 2019).

63De Munter André (2020), “The Western Balkans”, Fact Sheets on the European Union, European Parliament, available at: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/factsheets/en/sheet/168/the-western-balkans (accessed 11 December 2020).

64Demjaha Agon and Peci Lulzim (2014), “Interethnic Relations in the Western Balkans: Implications for Kosovo”, Policy paper, Kosovar Institute for Policy Research and Development (KIPRED), n° 6/14, pp. 1-51.

65European Commission (2015), “Urgent Reform Priorities for the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia”, available at: https://ec.europa.eu/neighbourhood-enlargement/sites/near/files/news_corner/news/news-files/20150619_urgent_reform_priorities.pdf (accessed 6 May 2021).

66European Commission (2018a), “Commission Staff Working Document”, 2018 Communication on EU Enlargement Policy, Albania 2018 Report, Strasbourg, 17.4.2018 SWD (2018) 154 final, pp. 1-107, available at: https://ec.europa.eu/neighbourhood-enlargement/sites/near/files/20180417-albania-report.pdf (accessed 28 April 2021).

67European Commission (2018b), “Commission Staff Working Document”, 2018 Communication on EU Enlargement Policy, The former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia 2018 Report, Strasbourg, 17.4.2018 SWD (2018) 154 final, pp. 1-95, available at: https://ec.europa.eu/neighbourhood-enlargement/sites/default/files/20180417-the-former-yugoslav-republic-of-macedonia-report.pdf (accessed 28 April 2021).

68European Commission (2018c), “Commission Staff Working Document”, 2018 Communication on EU Enlargement Policy, Kosovo 2018 Report, Strasbourg, 17.4.2018 SWD (2018) 154 final, pp. 1-107, available at: 20180417-kosovo-report.pdf (europa.eu) (accessed 28 April 2021).

69European Commission (2020), Steps towards joining, available at: https://ec.europa.eu/neighbourhood-enlargement/policy/steps-towards-joining_en (accessed 26 January 2020).

70Freedom House (2019), “Freedom in the World Research Methodology”, Report, available at: https://freedomhouse.org/reports/freedom-world/freedom-world-research-methodology (accessed 23 February 2020).

71Freedom House (2020), “All Data: Nations in Transit 2005-2020, Comparative and Historical Data Files”, Freedom House, available at: https://freedomhouse.org/report/nations-transit (accessed 2 May 2021).

72Krasniqi Afrim (2018), “Impakti i praktikës eksperimentale me ministra teknikë gjatë zgjedhjeve parlamentare 2017: Monitorimi dhe rekomandime përmirësuese të problematikave të rolit të ekzekutivit në zgjedhje në të ardhmen”, Institute for Political Studies, Tiranë, pp. 1-18, available at: http://isp.com.al/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/ISP-STUDIM-MBI-EKSPERIMENTIN-ME-MINISTRA-TEKNIKE-NE-ZGJEDHJET-2017.pdf (accessed 2 February 2019).

73Martínez J. G. Francisco et al. (2018), “Kosovo, World Development Indicators”, Freedom House, available at: https://freedomhouse.org/sites/default/files/NiT2018_Kosovo.pdf (accessed 11 March 2019).

74Rrustemi Arlinda et al. (2019), “Geopolitical Influences of External Powers in the Western Balkans”, Report, The Hague Center for Strategic Studies (HCSS), September 30th, pp. 1-208.

75United Nations Development Programme Albania (UNDP) (2018), “Religious tolerance in Albania”, Report, Tirana, Albania, pp. 1-94.

76Official documents

77Ohrid Framework Agreement (2001), Framework Agreement, pp. 1-14, available at: https://www.osce.org/files/f/documents/2/8/100622.pdf (accessed 10 January 2019).

78Partners Albania for Change and Development (2017), “Monitoring Matrix on Enabling Environment for Civil Society Development”, Country Report for Albania 2016, pp. 1-69, available at: https://partnersalbania.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/Monitoring_Matrix_Albania_Country_Report_2016.pdf (accessed 10 February 2018).

79Republic of Kosovo (2016), Kosovo – EU High Level Dialogue on Key Priorities, European Reform Agenda (ERA), Prishtina, available at: http://www.mei-ks.net/repository/docs/era_final.pdf (accessed 15 January 2019).

80Stiftung Bertelsmann (2018), “Kosovo: Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index (BTI)”, Country Report, (Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung), pp. 1-40, available at: https://www.bti-project.org/content/en/downloads/reports/country_report_2018_RKS.pdf (accessed 10 February 2018).

81The State Statistical Office (2002), Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in the Republic of North Macedonia, Book Xiii, The State Statistical Office, “Dame Gruev” – 4, Skopje/Shkup.

82Research data

83Chesdata (2014), 2014 CHES Candidate Survey, available at: https://www.chesdata.eu/2014-ches-candidate-survey (accessed 10 February 2019).

84Press articles

85Bota Sot (2019), “Marrëveshja PD-PS, 2 vite pas qeverisë teknike politika përsëri në krizë”, 18 Maj, available at: https://www.botasot.info/shqiperia/1087524/marreveshja-pd-ps-2-vite-pas-qeverise-teknike-politika-perseri-ne-krize/ (accessed 11 February 2019).

86Bytyçi Fatos (2018), “Kosovo parliament ratifies border deal with Montenegro after stormy session”, Reuters, available at: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-kosovo-parliament-teargas-idUSKBN1GX1GB (accessed 12 April 2018).

87Feilcke Adelheid (2019), “Albin Kurti: Nuk mund të ketë ndryshim të kufijve të Kosovës”, Deutsche Welle, available at: https://www.dw.com/sq/albin-kurti-nuk-mund-t%C3%AB-ket%C3%AB-ndryshim-t%C3%AB-kufijve-t%C3%AB-kosov%C3%ABs/a-51637941 (accessed 2 May 2021).

88Harris Chris (2019), “Greece and FYR Macedonia name dispute: the controversial feud explained”, Euronews, available at: https://www.euronews.com/2019/01/24/explained-the-controversial-name-dispute-between-greece-and-fyr-macedonia (accessed 9 January 2018).

89Lika Liridon (2020), “Ballkani Perëndimor mes integrimit europian dhe shtrirjes së ndikimit të fuqive në ngritje e sipër”, Gazeta Express, available at: https://www.gazetaexpress.com/ballkani-perendimor-mes-integrimit-europian-dhe-shtrirjes-se-ndikimit-te-fuqive-ne-ngritje-e-siper/ (accessed 3 May 2020).

90Marusic Sinisa (2018), “North Macedonia Passes Albanian Language Law”, BIRN, Skopje/Shkup, available at: https://balkaninsight.com/2018/01/11/macedonia-passes-albanian-language-law-01-11-2018/ (accessed 23 February 2018).

91Pajaziti Naser (2015), “Debates on the wiretapping inquiry committee”, Independent Balkan News Agency, Skopje/Shkup, available at: https://balkaneu.com/debates-wiretapping-inquiry-committee/ (accessed 15 February 2019).

92Top Channel (2018), “Protesta, studentët përpilojnë kërkesat e panegociueshme”, Top Channel, available at: https://top-channel.tv/2018/12/09/protesta-studentet-perpilojne-kerkesat-e-panegociueshme/ (accessed 10 January 2019).

Annexes

Annex 1: List of abbreviations of political parties

|

Country |

Party Abbrev |

Party name |

Party Name (English) |

|

Kosovo |

AAK |

Aleanca për Ardhmërinë e Kosovës |

Alliance for the Future of Kosovo |

|

AKR |

Aleanca Kosova e Re |

New Kosovo Alliance |

|

|

LDK |

Lidhja Demokratike e Kosovës |

Democratic League of Kosovo |

|

|

LVV |

Lëvizja Vetëvendosje! |

Self-Determination Movement! |

|

|

NSD |

Nisma Social-Demokrate |

Social Democratic Initiative |

|

|

PDK |

Partia Demokratike e Kosovës |

Democratic Party of Kosovo |

|

|

SL |

Srpska Lista |

Serb List |

|

|

North Macedonia |

PDSH |

Partia Demokratike Shqiptare |

Democratic Party of Albanians |

|

BDI |

Bashkimi Demokratik për Integrim |

Democratic Union for Integration |

|

|

GROM |

Gragjanska opcija za Makedonija-koalicija |

Citizen Option for Macedonia-led coalition |

|

|

RDK |

Rilindja Demokratike Kombëtare |

National Democratic Revival |

|

|

SDSM |

Socijaldemokratski Sojuz na Makedonija |

Social Democratic Union of Macedonia |

|

|

VMRO-DPMNE |

Vnatrešna makedonska revolucionerna organizacija-Demokratska partija za makedonsko nacionalno edinstvo |

Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization-Democratic Party for Macedonian National Unity |

|

|

Albania |

LSI |

Lëvizja Socialiste për Integrim |

Socialist Movement for Integration |

|

PBDNJ |

Partia Bashkimi për të Drejtat e Njeriut |

Unity for Human Rights Party |

|

|

PD |

Partia Demokratike e Shqipërisë |

Democratic Party of Albania |

|

|

PDIU |

Partia Drejtësi, Integrim dhe Unitet |

Justice, Integration and Unity Party |

|

|

PKDSH |

Partia Kristian Demokrate e Shqipërisë |

Christian Democratic Party of Albania |

|

|

PR |

Partia Republikane Shqiptare |

Albanian Republican Party |

|

|

PS |

Partia Socialiste e Shqipërisë |

Socialist Party of Albania |

Notes

1 Refer to annex 1 for the list of abbreviations of political parties.

2 Organisation for Security and Coopération in Europe/Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights.

3 The argument of the citizens’ perceptions is analyzed in detail in the last section of this article.

4 In North Macedonia there are some other Albanian ethnic political parties, such as Alliance for Albanians (AA) founded in 2015, Alternativa (A) founded in 2018 and Movement Besa (BESA) founded in 2014. Their main goal is to achieve full national equality between Albanians and North Macedonians in all areas. These parties are not included in the statistical analyze of this article because they are established after the data from CHES 2014 is gathered. In overall, these parties favor the EU integration, and do not constitute a factor of hindering this process.

5 The reading procedure is the same in all figures and tables that presents this institution data for civil society and media, in all years included in the analyze, for all the three countries: a rating of 1 indicates the highest degree of freedom and 7 the lowest level of freedom (Freedom House, 2019).

Pour citer cet article

A propos de : Dorina Bërdufi

Dorina Bërdufi, PhD in Political Science, is a lecturer at Political Science Department of the Aleksandër Moisiu University, Albania. She is also a political research expert. Her expertise is in political parties, governance and political research methods. She is the author of several research articles in her field of expertise. Her academic work is parallel to national and international research projects with main emphasis in social and political challenges of the Albanian citizens, such as: political party finance, Balkan comparative electoral study, administrative territorial division of 2015 in Albania, transparency monitoring of administrative juridical behavior and Albanian voting behavior. E-mail: berdufidorina@gmail.com