- Startpagina tijdschrift

- 2/2021 - Special issue Western Balkans, European U...

- Connectivity and international production networks in the Western Balkans: to what extent can China erode the economic dominant position of the EU?

Weergave(s): 5461 (15 ULiège)

Download(s): 0 (0 ULiège)

Connectivity and international production networks in the Western Balkans: to what extent can China erode the economic dominant position of the EU?

Abstract

The purpose of this article is to assess the impact of the Chinese economic penetration in the Western Balkans (Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Serbia) on the relation of this region with the European Union (EU) and on the role of this region in the international division of labour. Using international economics and international political economy theoretical concepts, this article outlines an interpretation of relevant quantitative data and a qualitative analysis of the Chinese economic flows in the Western Balkans. The results highlight that China is unlikely to challenge the economic hegemonic position of the EU in the region. The article also shows that the Chinese economic flows and development projects, notably the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), are not significantly transforming the peripherical role of the Western Balkans in the international division of labour. It explains why Chinese economic flows do not contribute substantially to the insertion of these economies in the international production networks set up by Chinese firms.

Inhoudstafel

Introduction

1The purpose of this article is to assess the impact of the Chinese economic penetration in the Western Balkans (Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Serbia) on the relation of this region with the European Union (EU). Using international economics and international political economy theoretical concepts, this article outlines an interpretation of relevant quantitative data and a qualitative analysis of the Chinese economic flows in the Western Balkans. It will analyse the rise of Chinese Outward Development Investment (ODI), trade and Official Development Aid (ODA) in the region and then attempt to show if the Chinese investments, infrastructure projects, notably since the implementation of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), can change substantially the traditional role of the Western Balkans in the international division of labour and challenge the EU hegemonic position in this region in terms of economic influence.

2All these elements highlight the rise of China’s influence in the region and raises important questions. What will be the impact of these economic flows coming from China on these domestic economies in terms of development? In terms of economic interdependency with China and with the other trading partners of the Western Balkans? Will it generate financial dependency vis-à-vis China? Will it significantly facilitate the integration of this region to the global economy? Will it generate a change for the Western Balkans in the international division of labour thanks to Chinese investment, technology transfers and ODA?

3To address these questions, this article will start with a first section that will outline what China’s motives behind the creation of a Balkan Silk Road. Then the second section will put China and EU economic penetration in the region in perspective, revealing that the EU remains by far the largest economic partner of the region. The third section will demonstrate that China’s BRI has not managed to move the Western Balkans out of the EU economic periphery. The fourth section will assess the level of Chinese influence in the regions and the limits of its attractiveness for the Western Balkans economies relatively to the EU. These different sections will enable to develop robust concluding remarks on our research questions.

China marches West…to Europe and builds a Balkan Silk Road

4China’s global commercial expansion accelerated in the early 2000s with its accession to the World Trade Organisation (WTO). At the run of the millennium, the government adopted a go-global strategy to encourage the internationalisation of China’s largest firms in key strategic industries (Economy and Levi, 2014; Kroeber, 2016). Despite four decades of economic reforms that moved away from central planning and state-controlled trade, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) continues to develop a global economic strategy inspired from Marxist theories on imperialism and similar to the approach taken by Friedrich List in his national system (Defraigne and De Meulemeester, 2009). Under this prism, the multinational enterprises (MNE) from the most advanced economies dominate the world economy through their control on international production networks (IPN) thanks to their innovation capacities and management know-how. To preserve national sovereignty from economic imperialism, the Chinese state is pursuing an active industrial policy to enable national champions in strategic industries to move up the value chain (Nolan, 2012). The state has rationalised production capacities by merging national firms to create Chinese global competitors aiming at setting up their own IPNs and challenge the Western and East Asian MNEs (Defraigne, 2020). A way to acquire faster technology for these Chinese champions was to engage into strategic-assets (Foreign Direct Investment (FDI)) and try to capture management and innovation know-how by taking over firms from more advanced economies (Clegg and Voss, 2014). Not all Chinese ODI in Europe are strategic-asset-seeking. Some are resource-seeking, notably in mining and energy, other are market-seeking to serve local markets better. Some Chinese investors are simply rent-seekers trying to diversify geographically and to secure their assets by investing out of China where property rights remain insecure and where the domestic economic slowdown has generated numerous manufacturing overcapacity and real estate instability (Magnus, 2018; Defraigne and Nouveau, 2017).

5The Chinese ODI flows began to accelerate after 2008 and reached a peak in 2016 (Huang et al., 2019), Europe becoming one of the most targeted regions by Chinese MNEs mergers and acquisitions (Sepulchre and Le Corre, 2018). However, the Western Balkans remained a marginal destination in the 2000s as China’s ODI in Europe (Hanemann and Huotari, 2018; Central Bank of Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2019; Bulgarian National Bank, 2019; Bank of Albania, 2019; Croatian National Bank, 2019; Holzner and Schwarzhappel, 2018). They did not constitute an important market and had barely any strategic assets in terms of technology and management know-how, the most important determinants for Chinese ODI in Europe (Defraigne and Nouveau, 2017).

6The Western Balkans gained in importance in the aftermath of the 2008 global crisis and of the slowdown of the Chinese economy after 2012. With outbursts of protectionism across the globe and rising trade frictions with the United States (US), securing the access to European markets became increasingly important in the eyes of Chinese authorities. In the early 2010s, the US under the Obama administration developed a commercial and security diplomacy that could be perceived as a strategy to keep its economic and geopolitical hegemonic position by isolating China (Wouters et al., 2020). From the “Pacific Century” concept development by the secretary of state Hillary Clinton and Obama’s “pivot to Asia” to the launching of the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) and the inclusion of Japan in the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TTP), the US were developing a strategy that would guarantee a privileged access to the most important markets compared to Chinese competitors while strengthening the US geopolitical position in Pacific Asia (Clinton, 2011; Defraigne, 2020). This development prompted reaction in Beijing, prominent scholars such as Beida’s Wang Jisi began to argue for a diplomatic and commercial to the Western (西进 or March West) to counter’s Obama’s pivot in Asia Pacific (Yu Sun, 2013).

7In 2011, the Chinese authorities developed the 16+1 framework to strengthen economic cooperation between China and the “European Community” (a China-made label) which included the new EU member states from Eastern Europe and most of the non-EU Balkans states1. In the spring of 2019, Greece formally joined the group re-labelled Cooperation between China and Central and Eastern European Countries (China-CEEC) (Xinhua, 2019).

8In 2013, Xi Jinping announced the One Belt, One Road (OBOR) project that was relabelled as the BRI or the New Silk Roads. This ambitious project aimed at fostering the economic integration of the Eurasian continent by improving transport and energy infrastructure across more than 60 countries, on the Eurasian continent and its neighbourhood (Southeast Asia islands and some close African countries) over a 36 years period (2013-2049) (Griffiths, 2017; Rolland, 2017). OBOR and BRI constitute a long-term strategy rather than a precise framework with clear budgets and targets. Different Chinese official sources have mentioned different amounts when they refer to the BRI-related funds to be spent and the list of recipient beneficiary countries has been evolving over time. However, relying on various Chinese and Western sources, the amount of BRI allocated funds is important. Relatively to the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of the recipient countries, there are below those spent by other important regional infrastructure projects such as the Marshall Plan (1947-1952) or the EU pre-accession to the new East European member states (2000-2007) (Defraigne, 2020).

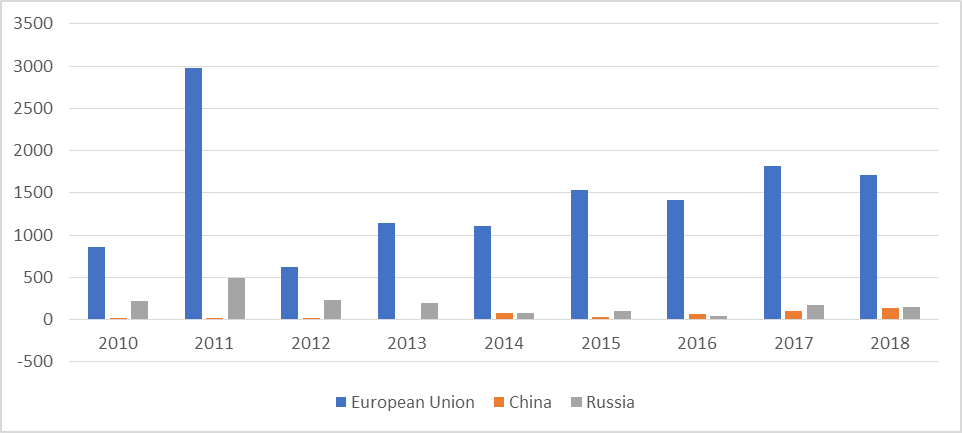

9The BRI focused on the development of seven corridors to facilitate trade. BRI had a range of various motives. Some motives were domestic driven like the better integration of China’s Western provinces (and particularly of the politically unstable province of Xinjiang) or creating outlets for industries burdened by overcapacity after the Chinese economic slowdown (Rolland, 2017; Clark, 2019). Some others were geopolitical like finding alternative routes (notably to the Strait of Malacca) to secure China’s access to markets and strategic raw materials in case of tensions with the US (Rolland, 2017). Some were part of a strategy to counter the US trade diplomacy and to provide a privileged access to markets across the Eurasian continent, including the EU (Wouters et al., 2020).

10Because of this last objective, there have been claims that the Western Balkans suddenly gained in importance for the Chinese state and the Chinese investors. Indeed, since China Ocean Shipping Company (COSCO) took over the Piraeus port in 2016, it has climbed up from behind the 20th to the 7th in the ranking of the most important ports of Europe as Greece has become a major entry point for Chinese exports to the EU. A BRI related scheme has started the building of a Piraeus-Skopje-Belgrade-Budapest corridor also called the “Balkan Silk Road” that would connect its Mediterranean access to central Europe and notably Germany (Bastian, 2017). In terms of ODA, China has become an important donor to develop transport and energy infrastructure projects in the Western Balkans, notably in Serbia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina (Holzner and Schwarzhappel, 2018; Beckmann-Dierkes, 2018; Le Corre and Vuksanovic, 2019; Sabbati et al., 2018).

Putting the Chinese and EU economic penetration in the Western Balkans in perspective

11The economic flows that assess the level of China’s and the EU’s economic penetration in the Western Balkans can be divided in four main categories: trade, FDI, remittance and labour, and ODA.

Trade flows2

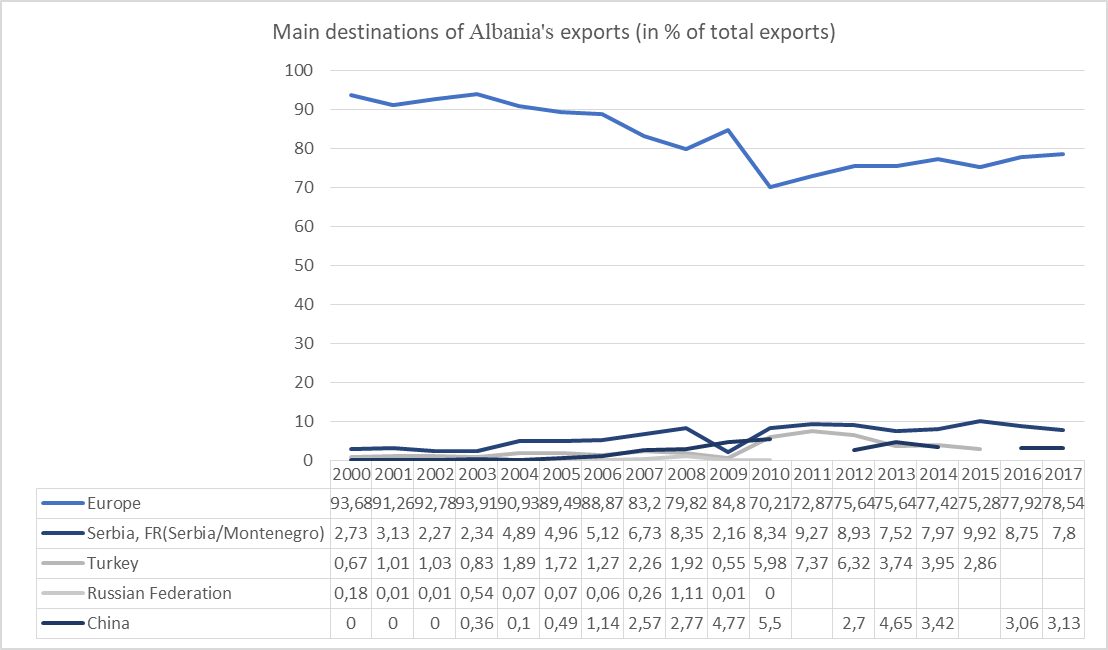

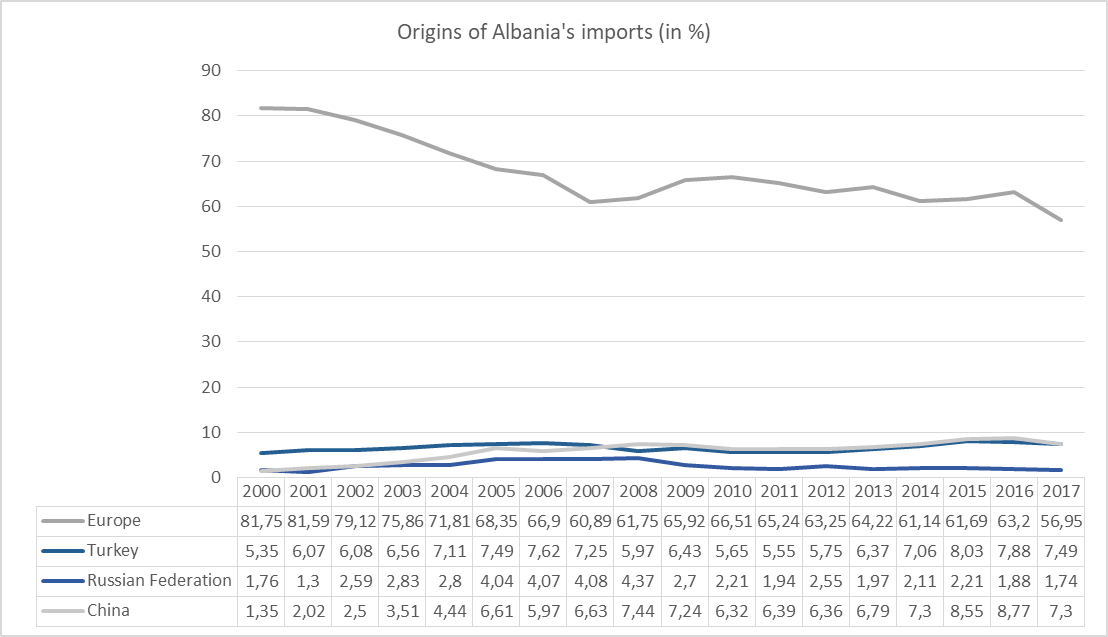

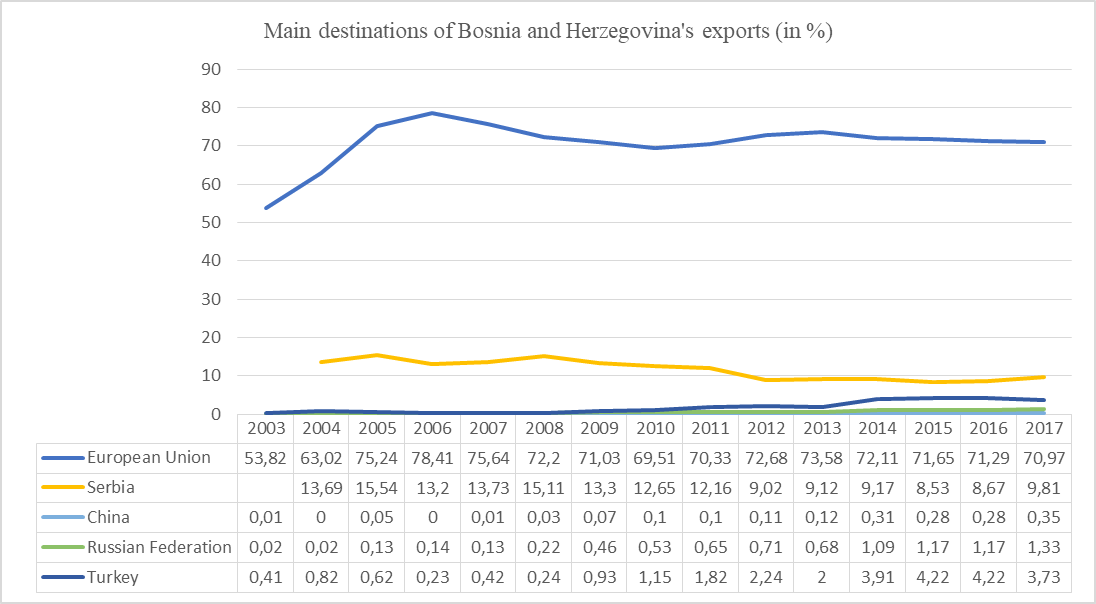

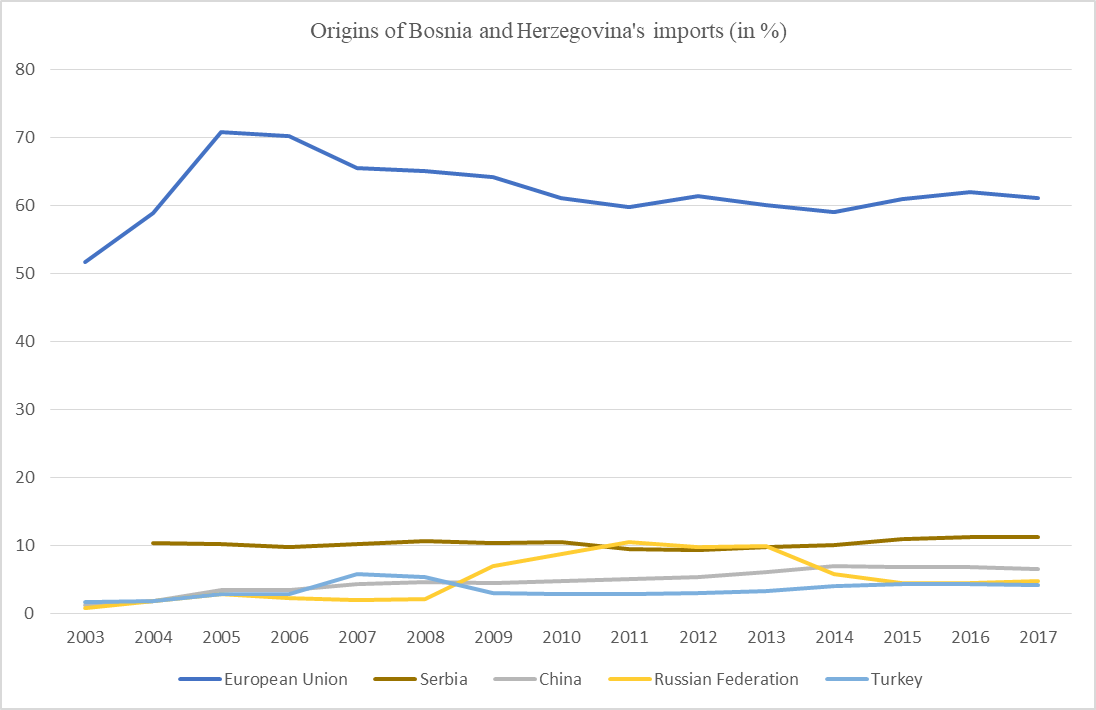

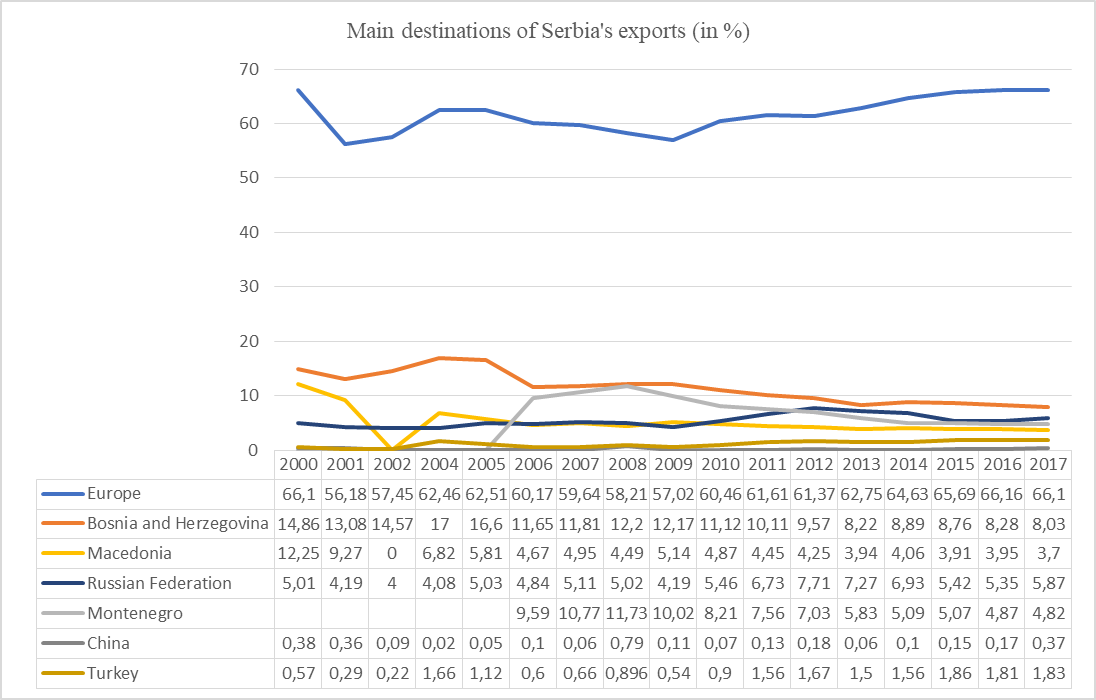

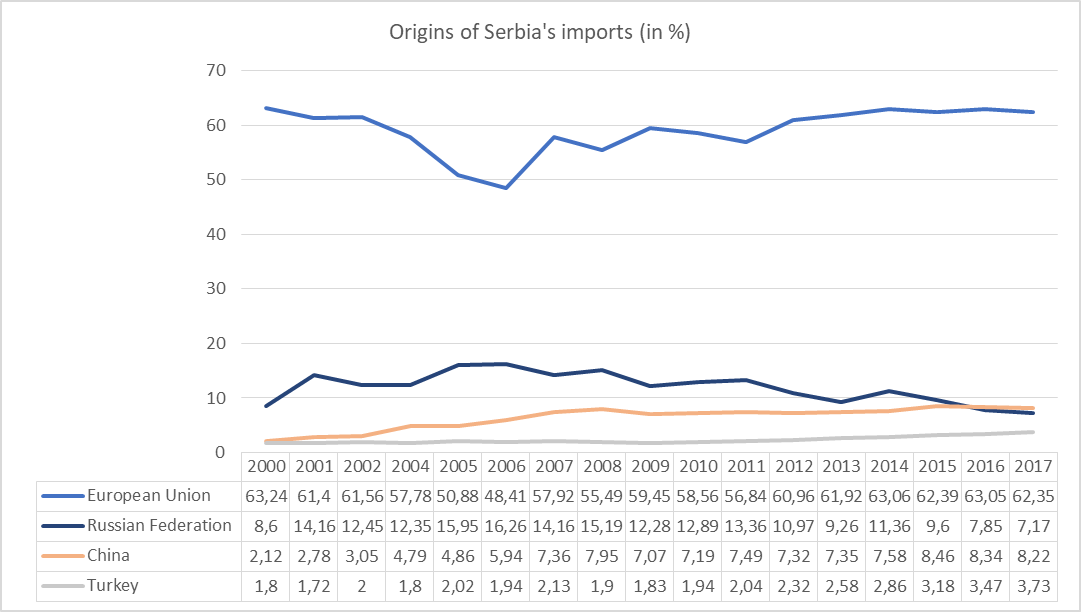

12The most obvious is trade and it clearly shows the rise of China’s share in the imports of the region at the expense of other trading partners, notably EU member states (OEC, 2019). This is a global phenomenon reflecting the competitiveness of Chinese manufactured exports. China is an increasingly important trade partner for the economies of the Western Balkans but still remains far behind the EU as a source of imports or as a destination for Western Balkans exports (OEC, 2019).

Table 1. Albania’s trading partners

13Source: OEC, 2019.

Table 2. Bosnia and Herzegovina’s trading partners

14Source: OEC, 2019.

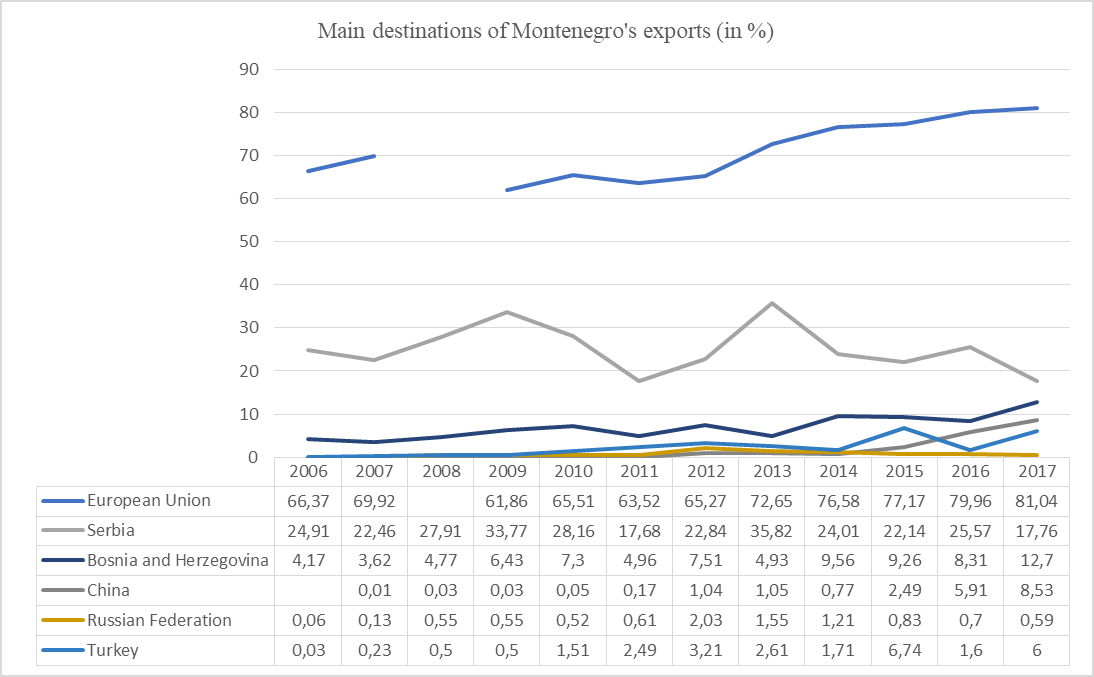

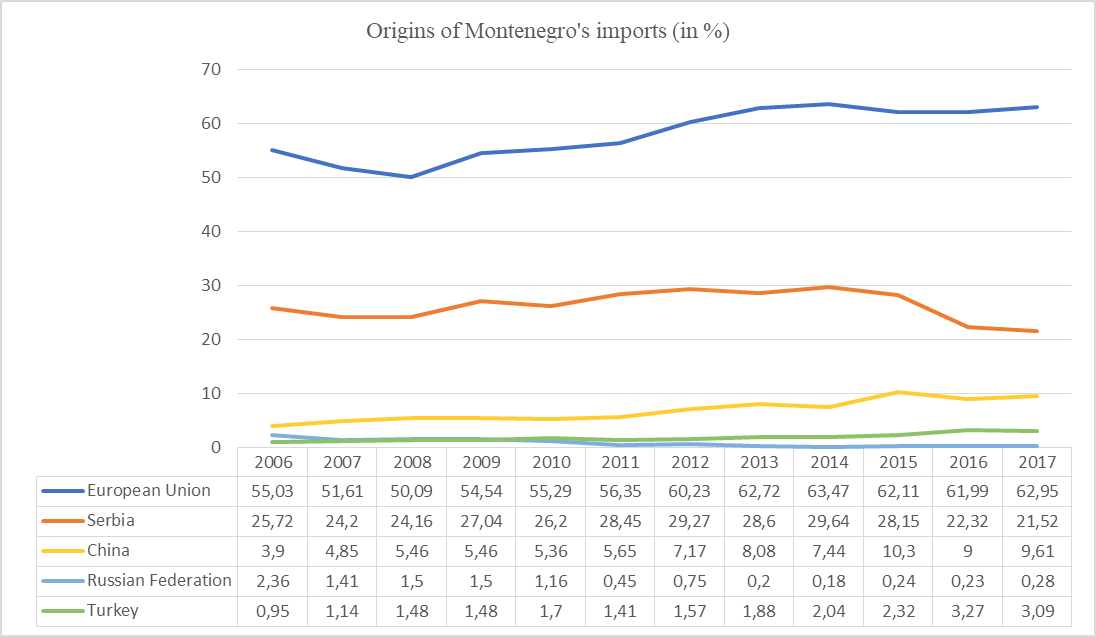

Table 3. Montenegro’s trading partners

15Source: OEC, 2019.

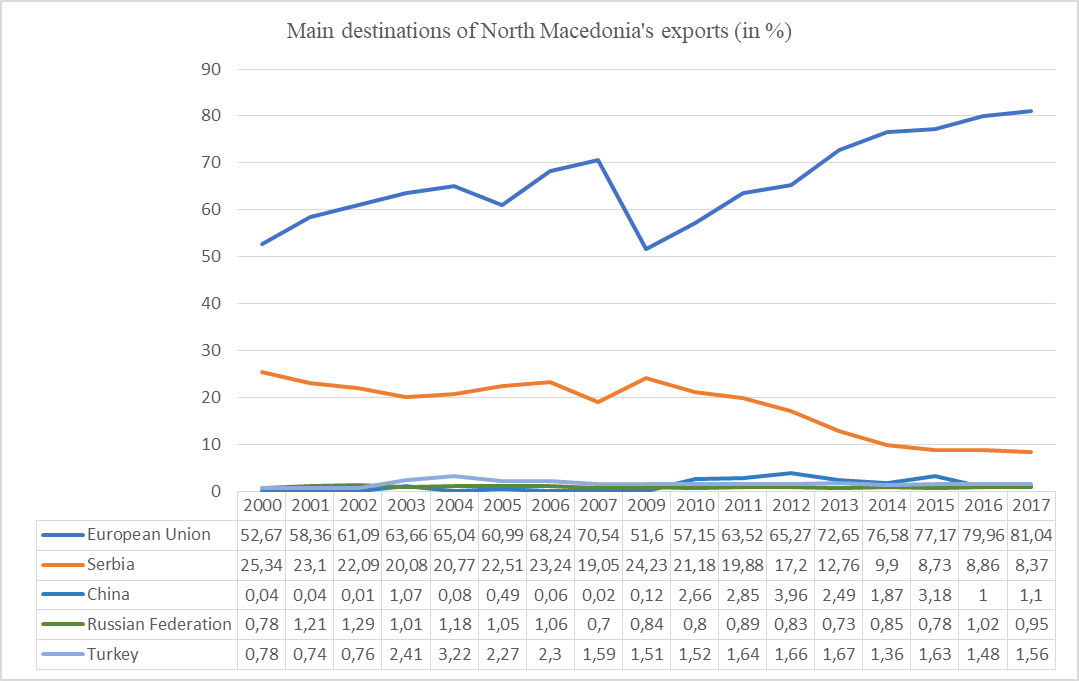

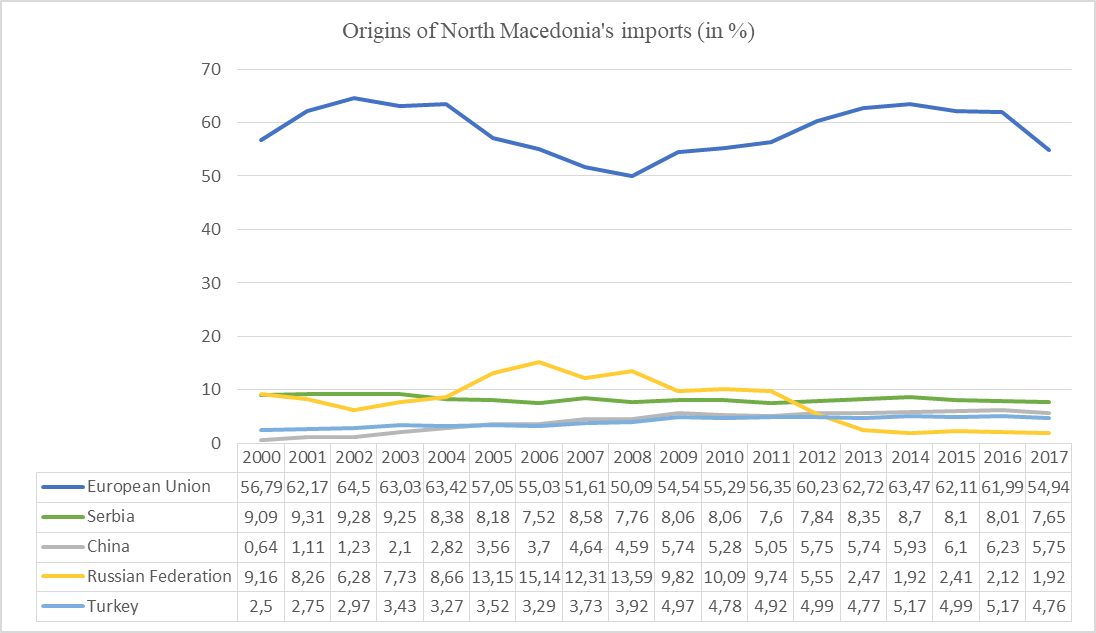

Table 4. North Macedonia’s trading partners

16Source: OEC, 2019.

Table 5. Serbia’s trading partners

17Source: OEC, 2019.

18The trade between the Western Balkans and China is characterized by Chinese basic manufactured products exchanged against Western Balkan raw materials, notably mineral products and tobacco. This reflects only a limited degree interdependency between these partners as most of this trade consist of relatively low-tech products widely offered on world markets. The Western Balkan trade with Western European countries includes more vertical intra-industrial trade due to the regionalization of the production process of Western MNEs. For example, the intrafirm trade organized by the Western European producers of cars (notably Fiat between Italy and Serbia), machine-tools, apparels and software that are relocating labour intensive activities to Serbia (OECD, 2018; Herasymchuk, 2019).

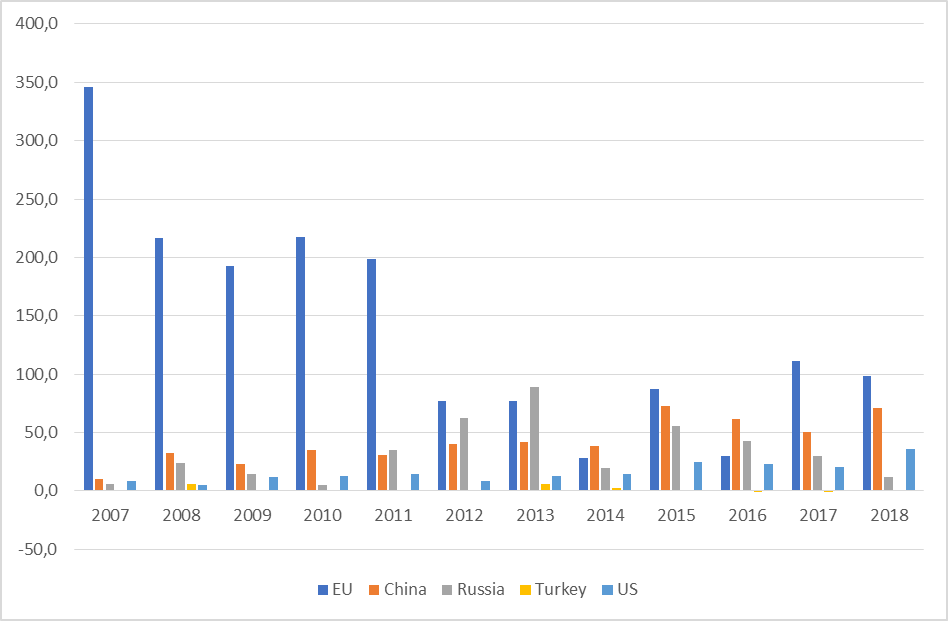

FDI

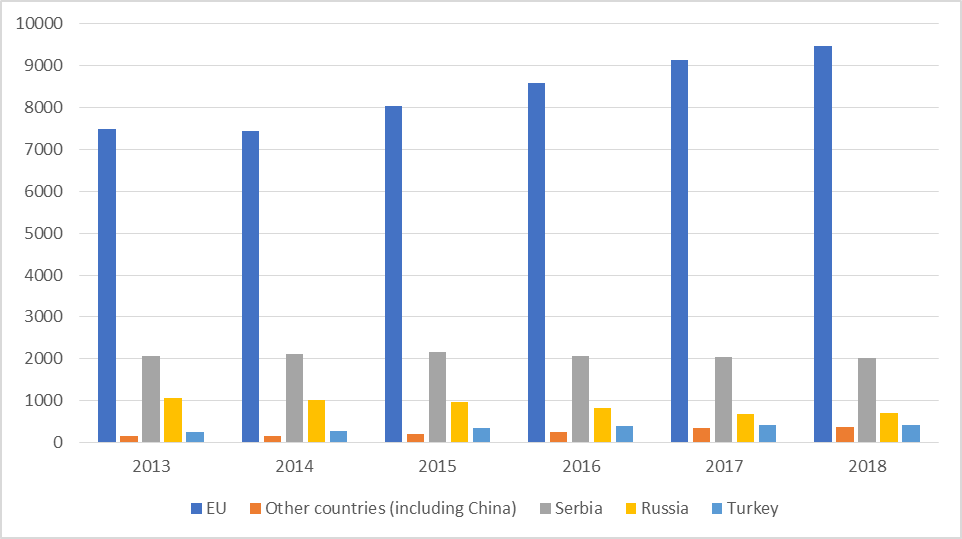

19In terms of FDI, some statistical sources are contradictory or incomplete. Despite significant discrepancies between standard sources on FDI (the national central banks of the Western Balkans, European Statistical Office (Eurostat), the Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies (wiiw), the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) world investment report), the main trends are very clear. Despite an increase in the 2010s for some countries, notably Serbia and Albania, China’s presence is very limited and not comparable to EU member states, Russia and Turkey (OECD, 2018; Central Bank of Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2019; Bulgarian National Bank, 2019; Bank of Albania, 2019; Croatian National Bank, 2019; Holzner and Schwarzhappel, 2018). The EU accounts for 82 % of the North Macedonia FDI stock in 2018 and was its largest investor in 2018 (European Commission, 2019). The EU was again the largest source of FDI for Montenegro between 2016 and 2019 before Russia, Serbia, Switzerland and Turkey; China not being present in the top ten investors (Mirkovic, 2019). China is therefore not even in the top five investors for any Western Balkan countries except possibly in Serbia if the recent promised investments materialize effectively (see tables 6 to 8 below).

Table 6. Origins of Serbia Inward FDI

20Source: National Bank of Serbia, 2019.

Table 7. Origins of Bosnia and Herzegovina Inward FDI

21Source: Central Bank of Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2019.

Table 8. Origins of Kosovo Inward FDI

22Source: Central Bank of the Republic of Kosovo, 2019.

23The EU dominance in terms of FDI should not be surprising. The size of the EU single market and its geographical proximity make it the natural economic centre of Eastern European and the Mediterranean regions. This economic importance of the EU comes from a flow of trade and investment that China cannot match. Firstly, there are the traditional medium-distance regional trade flows with EU member states neighbours. Secondly, EU Western member states, notably Germany, Italy and Austria have national firms that have outsourced some of their labour-intensive activities to the Western Balkans to benefit from their relatively cheap and more flexible labour force. MNEs but also many Small Multinational Enterprises (SME) have inserted the Western Balkans into the regionalization of their production process because of their geographical (and sometime cultural) proximity, their weaker labour and environmental standards and their relatively low wages (Defraigne and Nouveau, 2017). These Western European firms keep the activities that require a high level of Research and Development (R&D) and management know-how, and outsource to local subcontractors and subsidiaries the labour-intensive activities, generating a regional division of labour based on complementarity between North Western Europe and Eastern Europe, including the Western Balkans.

24Because it is still not as developed as the most advanced Western economies or Japan, the Chinese economy cannot offer a similar level of complementarity. Only a handful of large and experienced Chinese MNEs willing to organize a production network to serve the European market could also engage into efficiency-seeking FDI across the Western Balkans like some Western European MNEs. However, when compared to the Chinese economy, the small wage differential and the limited competitive advantages offered by the Western Balkan region does not encourage the Chinese firms that are exporting to the European markets (the EU and the European Free Trade Area (EFTA)) to insert the Western Balkans into their production networks and relocate labour-intensive activities in this region. In the future, as more very large Chinese firms will gain intangible assets in management know-how and in innovation such as Huawei, one should expect more Chinese efficiency-seeking investment across Europe as the large Chinese MNEs will follow their Western European, East Asian and US counterparts into regionalizing their production process across Europe to serve the European markets. Then, these Chinese MNEs might insert the Western Balkans into their international production network. However, only a handful of Chinese MNEs have reached this level of sophistication so far and they have chosen other European states than the Western Balkan economies to build their regional production networks across Europe. For these reasons Western Balkans’ intra-industrial vertical trade is mostly directed to Western European economies and remains insignificant with China in the 2010s.

25Chinese investments in the Western Balkans are mostly resource-seeking and market-seeking. Important resource-seeking ODIs have taken place in Albania and Serbia. In Albania in 2014, Jiangxi Copper Company has acquired a 50 % stake in Beralb Ltd specialized in copper mining for 65 million dollars. In 2016, for 575 million dollars, Geo Jade, specialized in oil, gas and property, has acquired a concession for the largest Albanian oil field, accounting for over 95 % of the national production of crude oil (Hackaj, 2019). In Serbia, the Zijin Mining Group acquired in 2018 63 % of RTB Bor, specialized in copper mining and smelting for 1.26 billion dollars (Jamasmie, 2018). Part of these raw materials are sent to fulfil the important needs of the Chinese economy. These Chinese ODIs have enabled to save some of these mining activities whose sustainability was threatened by the lack of investment to modernize their equipment and by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) demands for reduced government subsidies. However, this type of ODI has traditionally limited spill over effects on the domestic economy. It tends to reinforce the role of commodity provider played by Western Balkan economies towards China and therefore block it in a low-tech position in the international division of labour.

26Some significant Chinese ODI were also made in manufacturing activities in Serbia. In metallurgy, Zelezara Smederovo was bought by Hebei Iron and Steel (HBIS) that invested in the production sites over 150 million dollars between 2016 and 2018. The modernization enabled this company to become one the largest source of Serbia’s manufactured exports (Hackaj, 2019).

27Other investments have been made in car manufacturing, an industry for which some of the Western Balkans, notably Serbia and North Macedonia, have already developed an expertise and attracted numerous investors (UNCTAD, 2019). Shandong Linlong, a major Chinese tire producer has built a new production unit for 800 million euros (Bjelotomic, 2019a). The Chinese car parts supplier Meita has made modest but numerous investments in Serbia since 2004 (EBRD, 2018). It can take advantage of a relatively qualified and cheap labour force to supply the main EU automotive producers like Citroen, Peugeot, Volvo, BMW and Mercedes Benz (EBRD, 2018). This type of investments could facilitate the insertion of the Serbian economy into the International Production Networks (IPN) of the global carmakers operating in the EU. These Chinese ODI in the automotive sector should let one overlook that non-Chinese investors remain dominant in the car industry of the Western Balkans. Fiat already has been producing cars in Serbia for over a decade. The cable producers Essex Europe (owned by the Korean Chabol LS) and Yazaki (Japan) have invested in Serbia in 2018. The German tire marker Continental has built a R&D centre in Novi Sad (UNCTAD, 2019). Van Hool and Dräxlmaier are also present in North Macedonia (Macedonia free zones authority 2019). Kosovo steel group supplies car parts for Western EU firms (OECD, 2018). VW is considering Serbia as a choice for the relocation of some of its production capacities from Western Europe (Bjelotomic, 2019b). Despite the presence of major producers and car part suppliers, to what extent can the Western Balkans manage to host a major sustainable business cluster in the automotive industry remains uncertain at this stage. Fiat’s plant in Serbia has experienced severe overcapacities since 2018 and the merger with PSA (Peugeot Société Anonyme) Group could jeopardize this production site (Facchini, 2019). VW’s decision to build a new plant in Serbia is still uncertain. The initial choice for this new car plant was Turkey but it has been changed due to geopolitical considerations and Romania as Bulgaria are also competing with significant subsidies to attract VW. The US car parts manufacturer Dura Automotive Systems that had promised to build a new plant in North Macedonia’s Skopje 2 Free Zone has filed for bankruptcy in the fall of 2019 (Church, 2019).

28Chinese firms have also taken over some activities in services, notably in banking and transport. One of the largest has been the acquisition of a concession on Tirana International Airport SHPK in October 2016 by China Everbright Limited but the airport was eventually sold by the Chinese investors to the Albanian conglomerate Kastrati in December 2020 (Tonchev, 2017; Petrushevska, 2020). Again, EU firms are also very present in banking and Vinci Airport investing in Tesla Belgrade airport (UNCTAD, 2019; Mešić, 2018). These market-seeking FDI in services might generate the Chinese commercial penetration of the Western Balkans but are unlikely to transform their role in the international division of labour as it did not for other developing countries in the last two decades in Latin America, in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) or on the African continent (Defraigne, 2016).

29Overall, Chinese firms ODI flows remain modest across the Western Balkans except in Serbia and Albania. Only the investments made in the steel and car industries, with their spill-over and potential technological upgrading could modify significantly Serbia’s export structure and facilitate its insertions in IPNs.

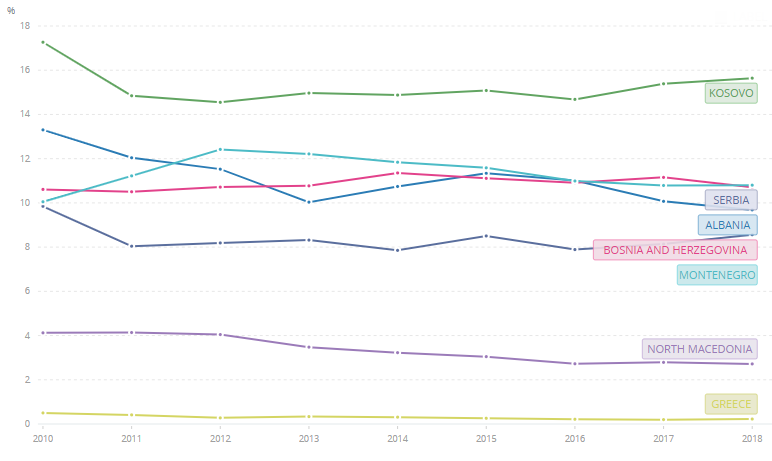

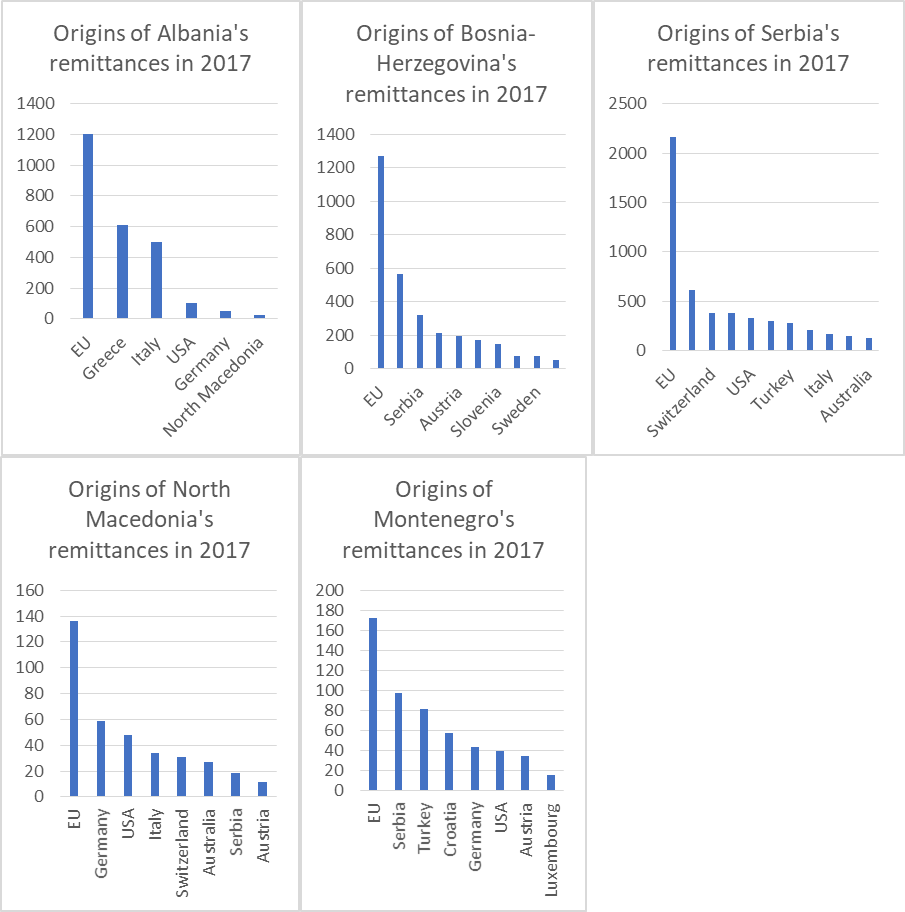

Remittances and labour flows

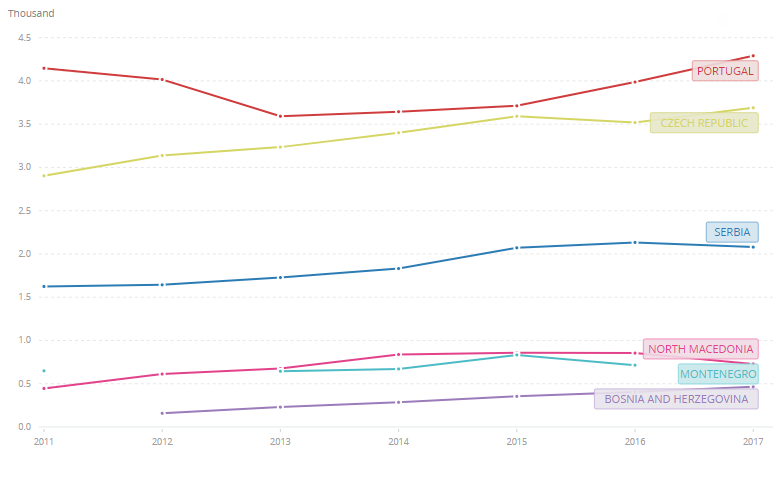

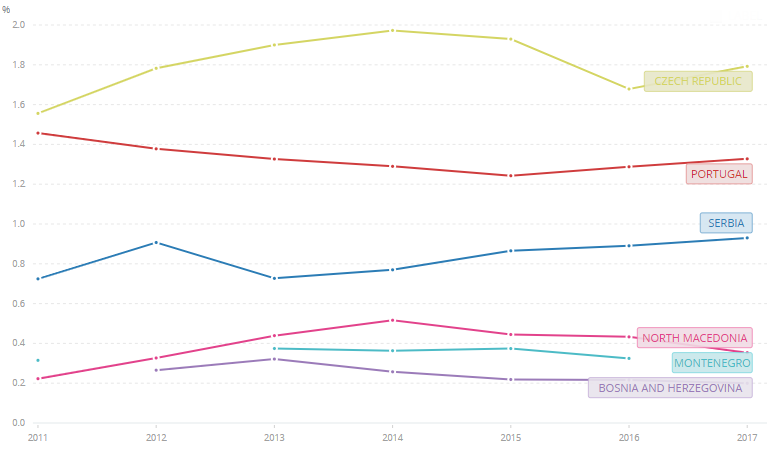

30In terms of remittances and labour flows, the EU remains the most important destination for the Western Balkans labour force and the most important source of remittance. China’s contribution is insignificant for all of the Western Balkan economies. Remittances are decisive as they constitute between 8 and 16 % of the GDP of these economies except for North Macedonia (see tables 9 and 10 below). This is much higher than Greece, a relatively poor EU member state. Geographical, linguistic and cultural proximity; the existence of the EU’s large immigrant communities originating from the Western Balkans; a better recognition of Western Balkans diplomas are factors that give again the dominant role to the EU and only a very marginal one for China. Labour emigration and remittances are essential for economies characterized by extremely high levels of unemployment and by structural trade deficits such as the Western Balkans.

Table 9. Contribution of remittances to the GDP of Western Balkans economies

31Source: World Bank Open Data, 2019.

Table 10. Origins of remittances3

32Source: World Bank Migration and Remittances Data, 2019.

ODA

33In terms of aid flows, the comparison is difficult as China does not abide by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development – Development Assistance Committee (OECD-DAC) methodology to assess ODA flows. The EU structural funds and various bilateral aid schemes between individual member states and Western Balkans economies are more important than the funds provided by China’s infrastructure projects backed by state-owned companies or China public financial institutions (Godement, 2016). The Western Balkan states benefit from Pre-Accession Assistance (IPA) and other EU aid schemes. Chinese amounts spent on infrastructure projects compare with EU aid flows only for Serbia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina (Holzner and Schwarzhappel, 2018; Beckmann-Dierkes, 2018; Le Corre and Vuksanovic, 2019; Sabbati et al., 2018).

34Regarding the degree of Chinese economic penetration, the Western Balkans are very heterogeneous (OEC, 2019; Holzner and Schwarzhappel, 2018). This is explained by economic and by geopolitical factors. From an economic standpoint, the region does not constitute a major and well-integrated market. For the Chinese authorities and even for other European actors, it is mostly seen as a transit route or as a pool of cheap labour by European standards. In the BRI, the Balkan Silk Road is one among others to reach the Western European market (one goes through Poland, another through Italy). Given the topography which makes connection costly and the limited size of local market, the Athens-Skopje-Belgrade-Budapest corridor is seen mostly as a mean to transit goods from the Piraeus Port to Central Europe. The linkages with the local economies of the Western Balkans are likely to be very limited except in the large industrial and populated area on the corridor itself (such as Athens, Belgrade or Budapest). Countries out of the axis and not well integrated such as Albania, Kosovo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Montenegro offer little interest in efficiency-seeking FDI and in logistics-related FDI, notably because of power shortages, weak infrastructure and unclear property rights (OECD, 2019). There are minor, by international standards, market-seeking investments in the less connected countries but these are unlikely to generate important spill-over in terms of innovation and management know-how. Geopolitically, Kosovo is not recognized by China4 who has chosen to privilege its relations with Serbia. Furthermore, Kosovo’s economy is fragile and is supported by international aid, specifically by the US and the EU. It has therefore not be seen as a priority for Chinese investors.

35Overall, the analysis of economic flows provided in this section clearly indicates that if China has become a significant economic partner of the Western Balkan economies mostly in terms of trade and ODA, the EU remains by far the most important economic partner of the region.

The BRI has not moved the Western Balkans out of the EU economic periphery

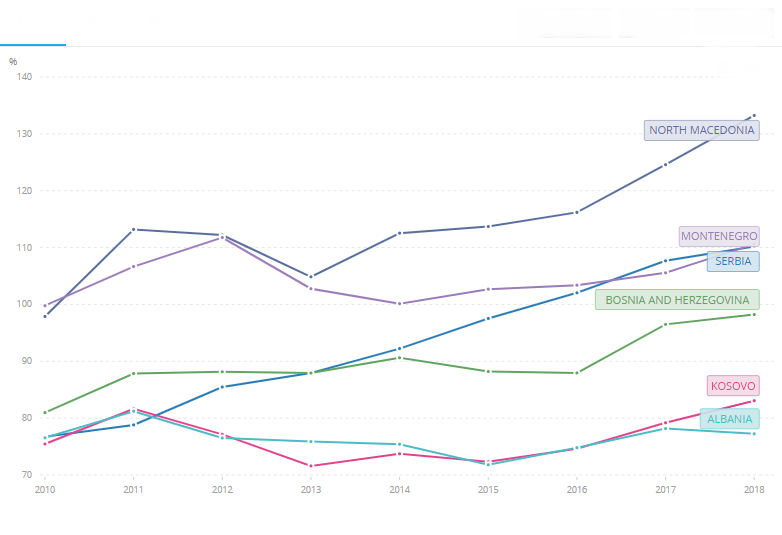

36Five years after the launching of the BRI in 2014 and their related infrastructure projects, it is too early to assess the final impact of the 36-year-long BRI and to what extent the improvement in terms of connectivity has facilitated the insertion of some Western Balkan economies into IPN. Nevertheless, it is possible to look at the evolution of key economic indicators of the most important beneficiaries of Chinese economic flows between 2014 and 2018 to see if they have experienced a major structural change that would upgrade their technological capacities, their level of income and substantially change their position in the international division of labour.

37Firstly, an analysis of the trade structure reveals few major changes. The opening of the economy (% of export to the GDP) does not seem to have accelerated after the BRI implementation in 2014. There is no obvious correlation between the opening of Western Balkans and the amount of Chinese ODI and BRI-related infrastructure projects. The opening trend started in Serbia, before Chinese investment became significant, and North Macedonia, where the opening has been the fastest, has not been a significant recipient of Chinese flows in the region (see table 11 below).

Table 11. Exports as % of GDP

38Source: World Bank Open Data, 2019.

39Western Balkans-China trade continues to be characterized by the exchange of raw materials versus manufactured products. The trade with Western Europe is somewhat more differentiated with significant levels of low-tech manufactured products exports from the Western Balkans, notably in garment and wires. This is consistent with qualitative studies highlighting the phenomenon of outsourcing of labour-intensive activities from Western European firms to the Western Balkan, as a periphery of EU. One important structural change in the exports of Serbia is the rise of automotive products but this is mostly explained by Italy’s Fiat greenfield FDI to build a new plant in the early 2010s (Harper, 2018). Some additional automotive equipment companies followed but remain predominantly European except for one recent Chinese firm of modest size by global standards (Ralev, 2019).

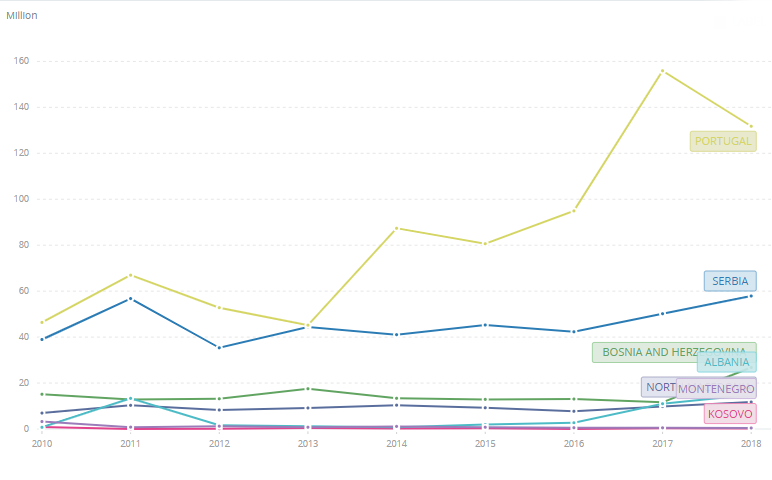

40Secondly, in terms of technological upgrading, the gap between the Western Balkans periphery and Western European firms has not been significantly reduced. On the contrary, for many of the Western Balkan countries, it has been widening after the 2008 crisis due to the economic slowdown; the public spending cuts in higher education; and the brain drain of the qualified labour forces attracted by the higher wages and better career’s prospects offered by the high-tech business cluster located in Western Europe and the US (Defraigne and Nouveau, 2017). Simple indicators such as the absolute amount of R&D spending, the share of GDP allocated to R&D and the number of top universities (not a single Western Balkan university make it to the Shanghai or Times Higher education rankings) all point out to an economic periphery status (see tables 12 to 14 below). Even though the recent progress in infrastructure like energy and transport should facilitate the insertion of the Western Balkan economies into Global Production Networks (GPN), their position in the international division of labour and therefore their standards of living have not increased significantly.

Table 12. Number of researchers per millions of people5

41Source: World Bank Open Data, 2019.

Table 13. R&D spending in % of GDP6

42Source: World Bank Open Data, 2019.

Table 14. Receipts for the use of intellectual property in millions of current dollars

43Source: World Bank Open Data, 2019.

44In the short and medium run, economic structural factors outlined earlier show why China is unlikely to replace the EU as the main economic centre for the Western Balkan periphery. The EU remains the largest and closest market, it hosts the largest recipient of the extra labour force from the Western Balkans, it provides most of the investments made in the region and insert some Western Balkan economies into IPNs better than Chinese firms and investments. This situation seriously reduces the room for manoeuvre of the Western Balkan governments vis-à-vis the EU and limits the extent of China’s economic and geopolitical influence.

China’s attraction and the limits of its influence

45Despite the central economic role of the EU, many governments in the Western Balkans have welcomed the BRI and have signed various economic agreements with China. This can be explained by various factors.

46Firstly, Eastern Europe and the Western Balkans have been particularly hit by the 2008 crisis. In 2009, it experienced a major credit crunch as a large part of their banking system was relying on Western European banks for credit access. Western European banks reduced the amount of loans in the region and their local subsidiaries in the South-Eastern Europe transferred liquidities to their headquarters in Western Europe. Faced with trade deficit that could not be financed, many of the South-Eastern Europe economies had to follow a painful adjustment characterized by austerity policies (Greece, Romania, Hungary) which explains the lack of investment that these countries experienced in the early 2010s. In this context, the Chinese project could fill an investment gap. Secondly, the EU aid is submitted to relatively strict conditionality and procedure imposed by the acquis communautaire. For some projects, the Chinese procedure is less demanding and therefore swifter. Thirdly, Western Balkan governments could also play the Chinese card to improve their bargaining position when negotiating economic agreements on EU market access, labour mobility, aid or even in renewing their case for an EU membership. Last but not least, many of the Western Balkans are characterized by weak states (Berend 2003). Historical path dependency explains the weakness of the civil society, of the labour movement and of the press. This situation has favoured the development of corruption, enabled a high degree of concentration of power and foster far right nationalist populism. These patterns have generated numerous tensions between the EU supranational institutions and many South-Eastern Europe governments, including EU member states like Romania and Hungary. Some Western Balkan governments challenged by EU institutions can use China’s aid and BRI-related projects as leverage in negotiations with the EU by showing that they can rely on an alternative source of funds. However, this deterrent has obvious limits as EU officials are aware of the EU central role. Nevertheless, it can increase the room for manoeuvre of some political elites. Corrupted governments might consider greater kickbacks by Chinese firms used to work in highly corrupted economies (Wedeman, 2012). One should not overstress the specificity of Chinese business in this domain as recent scandals in some Balkan economies have highlighted corruption practices in procurement involving Western EU member states or Russian firms and EU funds (Angelos, 2015; Rankin, 2017).

47These three factors explain why the Western Balkans, like some other Eastern European and Mediterranean economies, can be seen by the Chinese authorities as a vacuum to penetrate the EU markets in order to strengthen the economic integration between China and Europe and develop the BRI. Some Western officials, politicians and scholars have therefore highlighted the risk that China is increasing its geopolitical influence in the economic periphery of Europe (Hillman 2020; Prestowitz, 2021). Other examples of Chinese aid recipient countries have shown that it could well be the case (Goh, 2016) but two factors limit the rise of China’s influence in the region.

48Firstly, Eastern Europe, and the Western Balkans are seen as a natural export markets for the export-oriented economies, notably by Germany. Through their traditional lobbying, private firms from Western Europe are likely to pressure the EU and their member states governments to keep a privileged access to these markets and defend their market share versus Chinese competitors. For example, the German federation of industries (Bundesverband der Deutschen Industrie) has been very active in promoting the EU new connectivity strategy as a response to China’s BRI. The French state and the French business have a long tradition of diplomatic and commercial presence in Serbia that resumed after the collapse of the former Yugoslavia. These powerful member states will very likely limit the Chinese influence in the area.

49Secondly, some of the Western Balkan states have clearly opted for a strong alliance with the US. This has been the case of Albania, Kosovo and more recently Montenegro as it joined the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) (although Russian influence remains very significant in the latest case) (Feyerabend, 2018). Despite numerous tensions with the EU and important Chinese investments since 2008, Greece’s Tsipras government remains firmly in the West in the geopolitical field. The Tsipars government has confirmed the importance of its strategic ties with NATO and the US in 2017, committing to spend more than 2 billion dollars on US military equipment (Hope, 2017). The relatively small Western Balkan countries belonging to NATO and hosting US military bases have limited options in terms of foreign policy. The Chinese authorities are unlikely to confront the US directly in a fight for political influence. In this case, China tends to adopt a low-profile diplomacy focusing on strengthening economic ties to generate an increasing level of interdependency.

50Bosnia and Herzegovina and Serbia have been important recipient of Chinese aid (Holzner and Schwarzhappel, 2018) but are still seeking accession to the EU. Most Chinese projects in these two countries are made in energy and transport infrastructure. Some of these projects generate better infrastructure links between the Western Balkans and the EU. For this reason, Chinese authorities have an interest that these two countries reach the best possible economic agreements with the EU and possibly a full EU membership. This will maximize the efficiency of the Balkan Silk Road, starting from the Piraeus harbour in Greece to reach Central Europe. However, it will also mean that these countries will have to adopt an increasing part of the EU acquis communautaire, creating an EU controlled institutional framework on key issues such as local governance, state aid control, procurements access and competition law. These new standards and rules will be imposed on Chinese firms operating in these countries. This institutional transformation should increase the level of transparency, facilitate the Western European firms lobbying to shape local economic policies through European directives and regulations. On the one hand, the adoption of the EU acquis communautaire should contain China’s political leverage in these states. Yet, on the other hand, this phenomenon should increase the transit of trade from China to the EU Western member states through the Balkan Silk Road. These countries should experience an increasing economic interdependency with China but with the EU remaining the most influential power in the region.

Conclusion

51Given these elements, China is unlikely to become a major influential power in the region even if its trade will continue to grow. China remains a small investor and a less important donor than the EU, except maybe for Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina. Along with Greece, Serbia is the country of the South-Eastern Europe where Chinese economic penetration is the most important for geographical reasons (Serbia lays at the centre of the Balkan Silk Road) and economic reasons (Serbia is already more industrialized, better connected and with a large pool of qualified workers). However, China’s influence is likely to be stronger in Serbia than in Greece because of the geopolitical and historical context (Serbia adopts a neutrality strategy and refuses to join NATO and has strategic and economic ties with Russia) but it could be reduced in the future if Serbia joins the EU (Beckmann-Dierkes, 2018).

52The EU is still the economic regional centre for the Western Balkans that remains in its periphery. The EU economic magnet is so strong that it does not allow other powers such as China, Russia or Turkey to challenge substantially its hegemonic position. Economic dependency vis-à-vis the EU considerably restricts the diplomatic room for manoeuvre of local governments. As for Russia and Turkey, Chinese economic presence can be used as leverage to improve Western Balkan governments’ bargaining position when negotiating with the EU, but only marginally. It has not prevented in autumn 2019 the refusal of French president Emmanuel Macron to consider the launching of an EU enlargement towards Albania and North Macedonia. Due to long term structural historical and geographic factors, they remain in the periphery of the large and more advanced Western European economies and China’s magnet cannot yet challenge this situation in the short or medium run.

References

53Books

54Angelos James (2015), The Full Catastrophe, Inside the Greek Crisis, London: Head of Zeus.

55Berend Ivan (2003), History Derailed: Central and Eastern Europe in the Long 19th Century, Berkeley: University of California Press.

56Defraigne Jean-Christophe and Nouveau Patricia (2017), Introduction à l’économie européenne, Louvain-la-Neuve: De Boeck.

57Economy Elizabeth and Levy Michael (2014), By All Means Necessary, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

58Goh Evelyn (2016), Rising China’s Influence in Developing Asia, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

59Griffiths Richard (2017), Revitalizing the Silk Road, Leiden: Hipe.

60Hillman Johnatan (2020), The Emperor’s New Road, New Haven: Yale University Press.

61Kroeber Arthur (2016), China’s Economy, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

62Magnus George (2018), Red Flags: Why Xi’s China is in jeopardy, New-Haven: Yale University Press.

63Nolan Peter (2012), Is China buying the World?, Cambridge: Polity Press.

64Prestowitz Clyde (2021), The World Turned Upside Down, New-Haven: Yale University Press.

65Rolland Nadège (2017), China’s Eurasian Century, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

66Sepulchre Alain and Le Corre Philippe (2016), China’s offensive in Europe, Washington DC: Brookings Institution Press.

67Wedeman Andrew (2012), Double Paradox: Rapid Growth and Rising Corruption in China, Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

68Edited books

69Wouters Jan, Defraigne Jean-Christophe and Carai Maria Adele (eds.) (2020), The Belt and Road Initiative and Global Governance, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

70Chapters in an edited book

71Clegg Jeremy and Voss Hinrich (2014), “Chinese Overseas Direct Investment into the European Union”, in Brown Kerry (eds.), China and the EU in context, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 14-43.

72Defraigne Jean-Christophe (2020), “The BRI, the economic integration of the Eurasian continent and the international division of labour”, in Wouters Jan, Defraigne Jean-Christophe and Carai Maria Adele (eds.), The Belt and Road Initiative and Global Governance, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, pp. 34-75.

73Defraigne Jean-Christophe and De Meulemeester Jean-Luc (2009), “Le Système National de List. La fondation du réalisme pluridisciplinaire en économie politique internationale contre le libre-échangisme anglo-saxon”, in Diebolt Claude and Alcouffe Alain (eds.), La pensée économique allemande, Paris : Economica, pp. 227-243.

74Articles of scientific journals

75Mešić Dušan (2018), “Transformation of the Banking System in the Western Balkans”, Bankarstvo, vol. 47, Issue 4, pp. 86-107.

76Defraigne Jean-Christophe (2016), “La reconfiguration industrielle globale et la crise mondiale”, Outre-Terre : revue européenne de géopolitique, n° 46, Paris : édition l’Esprit du Temps, pp. 143-192.

77Research institutes

78Beckmann-Dierkes Norbet (2018), “Serbia and Montenegro”, in Feyerabend Florian C. (eds.), The influence of external actors in the Western Balkans: a map of geopolitical players, Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, Berlin, pp. 32-38, available at: https://www.kas.de/c/document_library/get_file?uuid=194afc48-b3be-e3bc-d1da-02771a223f73&groupId=252038 (accessed 27 February 2021).

79Hanemann Thilo and Huotari Mikko (2018), “EU-China FDI: Working towards more reciprocity in investment relations”, Report by Merics and Rhodium Group, Mercator Institute for China Studies, n° 3, Berlin, May 2018, pp. 1-39.

80Holzner Mario and Schwarzhappel Monika (2018), “Infrastructure Investment in the Western Balkans: A First Analysis”, European Investment Bank, The Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies (WIIW), Vienna, pp. 1-30.

81Huang Betty, Ortiz Alvaro, Rodrigo Tomasa and Xia Le (2019), “China: Five facts about outward direct investment and their implication for future trend”, BBVA Research, China Economic Watch, pp. 1-7, available at: http://www.iberchina.org/files/2019/china_odi_bbva.pdf (accessed 30 March 2021).

82Feyerabend Florian C. (eds.) (2018), The influence of external actors in the Western Balkans: a map of geopolitical players, Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, Berlin, pp. 1-40, available at: https://www.kas.de/c/document_library/get_file?uuid=194afc48-b3be-e3bc-d1da-02771a223f73&groupId=252038 (accessed 27 February 2021).

83Le Corre Philippe and Vuksanovic Vuk (2019), “Serbia: China’s Open Door to the Balkans”, Carnegie Endowment for Peace, January 1, available at: https://carnegieendowment.org/2019/01/01/serbia-china-s-open-door-to-balkans-pub-78054 (accessed 27 February 2021).

84Sabbati Giulo, Liliyanova Velina and Guidi Caterina Francesca (2018), Bosnia and Herzegovina: Economic indicators and trade with EU, European University Institute, Florence, pp. 1-2, available at:

85https://cadmus.eui.eu/bitstream/handle/1814/54204/EPRS_ATA%282018%29614775_EN.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed 30 March 2021).

86Tonchev Plamen (2017), “China’s Road: into the Western Balkans”, European Union Institute for Security Studies, 2017, pp. 1-4, available at: https://www.iss.europa.eu/sites/default/files/EUISSFiles/Brief%203%20China%27s%20Silk%20Road.pdf (accessed 30 March 2021).

87Reports

88Hackaj Ardian (2019), “Corporate China in the Western Balkans”, Cooperation and Development Institute – CDI, seminar report, Tirana, pp. 1-19, available at: https://cdinstitute.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Corporate-China-in-Western-Balkans-1.pdf (accessed 27 February 2021).

89Mirkovic Milika (2019), “Montenegro economy briefing: Overview of Foreign Direct Investment Trends in Montenegro”, China-CEE Institute, Budapest, pp. 1-4, at available: https://china-cee.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/2019e0778%EF%BC%889%EF%BC%89Montenegro.pdf (accessed 30 March 2021).

90UNCTAD (2019), “World Investment Report 2019”, New-York: United Nations Publications, pp. 1-222.

91Statistics and official documents

92Bank of Albania (2019), Statistics/External sector statistics/Foreign Direct Investments, available at: https://www.bankofalbania.org/?crd=0,8,1,8,0,18666&uni=20190729164619911768510741825722&ln=2&mode=alone (accessed 29 July 2019).

93Bulgarian National Bank (2019), Statistics, available at: http://www.bnb.bg/Statistics/StExternalSector/StDirectInvestments/StDIBulgaria/index.htm (accessed 29 July 2019).

94Central Bank of Bosnia and Herzegovina (2019), Statistics, available at: http://statistics.cbbh.ba/Panorama/novaview/SimpleLogin_en_html.aspx (accessed 29 July 2019).

95National Bank of Serbia (2019), Statistics, available at: https://www.nbs.rs/en/indeks/ (accessed 29 July 2019).

96Central Bank of the Republic of Kosovo (2019), Statistics, available at: https://bqk-kos.org/?lang=en (accessed 29 July 2019).

97Croatian National Bank (2019), Statistics, available at: https://www.hnb.hr/en/statistics/statistical-data/rest-of-the-world/foreign-direct-investments (accessed 29 July 2019).

98European Commission (2019), “North Macedonia 2019 Report”, Commission Staff Working Document, Accompanying the Document, Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions; 2019 Communication on EU Enlargement Policy, {COM(2019) 260 final}; Brussels, 29.5.2019, SWD(2019) 218 final, available at: https://ec.europa.eu/neighbourhood-enlargement/sites/near/files/20190529-north-macedonia-report.pdf (accessed 27 February 2021).

99OEC (2019), Observatory of Economic Complexity data, available at: https://oec.world/ (accessed 27 February 2021).

100OECD (2019), “Unleashing the Transformation Potential for Growth in the Western Balkans”, Global Relations, Policy Insights, pp. 1-234, available at: http://www.oecd.org/south-east-europe/programme/Unleashing_the_Transformation_potential_for_Growth_in_WB.pdf (accessed 27 February 2021).

101World Bank (2019), Open Data, available at: https://data.worldbank.org/ (accessed 27 February 2021).

102World Bank (2019), Worldwide Governance Indicators, available at: https://datacatalog.worldbank.org/dataset/worldwide-governance-indicators (accessed 27 February 2021).

103Press articles

104Bjelotomic Snezana (2019a), “China’s Linglong Tire allocated land for its factory in Zrenjanin”, Serbian Monitor, Belgrade, 28 March 2019.

105Bjelotomic Snezana (2019b), “Is Volkswagen going to pick Serbia for location of its new factory?”, Serbian Monitor, Belgrade, 21 October 2019.

106Clinton Hillary (2011), “America’s Pacific Century”, Foreign Policy, October 11, available at: https://foreignpolicy.com/2011/10/11/americas-pacific-century/ (accessed 27 February 2021).

107Facchini Duccio (2019), “La fusione FCA-Peugeot vista da Kragujevac, in Serbia, dove la Fiat sta scomparendo”, Altreconomia, available at: https://altreconomia.it/fusione-fca-peugeot-vista-da-kragujevac/ (accessed 27 February 2021).

108Harper Jo (2018), “Serbian automotive industry a rising star”, Financial Observer, October 20, available at: https://www.obserwatorfinansowy.pl/in-english/serbian-automotive-industry-a-rising-star/ (accessed 27 February 2021).

109Herasymchuk Olena (2019), “Where Do German and Dutch Companies Outsource Software Development?”, Daxx, available at: https://www.daxx.com/blog/development-trends/outsource-software-development-germany-netherlands-statistics (accessed 27 February 2021).

110Hope Kerin (2017), “Greek PM defends decision to buy US-made fighter jets”, Financial Times, London, October 27, available at: https://www.ft.com/content/b16bc236-bae6-11e7-9bfb-4a9c83ffa852 (accessed 30 March 2021).

111Jamasmie Cecilia (2018), “China’s Zijin wins race for Serbia’s largest copper mine”, Mining.com, August 31, available at: https://www.mining.com/chinas-zijin-wins-race-serbias-largest-copper-mine/ (accessed 27 February 2021).

112Macedonia Free Zones Authority (2019), “Macedonia automotive component sector”, Directorate for Technological Industrial Development Zones, Skopje, available at: http://fez.gov.mk/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/avtomobilska-brosura-komplet-za-web.pdf (accessed 27 February 2021).

113Petrushevska Dragana (2020), “Albania’s Kastrati Group acquires Tirana airport operator”, SeeNews, December 28, available at: https://seenews.com/news/update-1-albanias-kastrati-group-acquires-tirana-airport-operator-726150 (accessed 23 April 2021).

114Ralev Radomir (2019), “China’s Zhong Qiao, Turkey’s Feka Automotive to open factories in Serbia”, SeeNews, January 3, available at: https://seenews.com/news/chinas-zhong-qiao-turkeys-feka-automotive-to-open-factories-in-serbia-638357 (accessed 27 February 2021).

115Rankin Jennifer (2017), “Cloud of corruption hangs over Bulgaria as it takes up EU presidency”, The Guardian, December 28, available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/dec/28/bulgaria-corruption-eu-presidency-far-right-minority-parties-concerns (accessed 30 March 2021).

Voetnoten

1 Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, North Macedonia, Montenegro, Poland, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia and Slovenia.

2 Statistics on Kosovo’s trading partners are not available on the Observatory of Economic Complexity (OEC) and cannot be presented here with a similar methodology regarding data collection.

3 Origins of remittances for the Republic of Kosovo are not available on World Bank Data and cannot be presented here with a similar methodology regarding data collection.

4 Even though there are some commercial relations between the two countries.

5 Data for Albania and Kosovo are not available in the World Bank data set.

6 Data for Albania and Kosovo are not available in the World Bank data set.

Om dit artikel te citeren:

Over : Jean-Christophe Defraigne

Jean-Christophe Defraigne is professor in International and European Economics at the Institute for European Studies of Université Saint-Louis – Bruxelles and at the Louvain School of Management UCLouvain. He is also a research fellow at the Leuven Centre for Global Governance Studies of the KULeuven University. He has been visiting scholar and professor at UIBE Beijng (Jing Mao Da Xue) and Zhejiang Da Xue. As an academic expert, he has participated to numerous international research projects for various international and EU institutions. Among recent publications on related topics: “The Belt and Road Initiative and Global Governance”, Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, 2020; “Introduction à l’Economie Européenne”, 3ème édition, De Boeck, Louvain-La-Neuve, 2021.