- Accueil

- 5/2024 - Resilience of global regionalism in times...

- Fissure in South Asian regionalism in the age of great powers rivalry: a small state’s perspective

Visualisation(s): 2237 (20 ULiège)

Téléchargement(s): 0 (0 ULiège)

Fissure in South Asian regionalism in the age of great powers rivalry: a small state’s perspective

Document(s) associé(s)

Version PDF originaleRésumé

Homogeneity and geographical proximity alone are not sufficient in yielding effective regional cooperation. South Asian regionalism is an apt example. While the continuous and emerging inter-state conflicts, internal domestic challenges, and increasing footsteps of China into South Asia had already affected the geopolitical scenario and the process of regionalism in South Asia, the US-China rivalry has further complicated South Asian regionalism. Against this backdrop, the hopes and aspirations of landlocked countries like Nepal to draw benefits from the regional and sub-regional forums have been severely paralyzed amidst the foreign policy securitization of great powers and regional powers. India’s response to regionalism in South Asia is driven by two factors: isolating Pakistan and containing China. At the same time, Beijing, and Washington intend to lure the South Asian countries through aid and assistance. As such, the strategic interests of great powers in the region have incapacitated regionalism in South Asia. Despite being the incumbent chair of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC), Nepal is not in a position to propel the organization ahead. It is not only because of Nepal’s small state syndrome but more because of varying degrees of great power contestations in the region.

Table des matières

Introduction

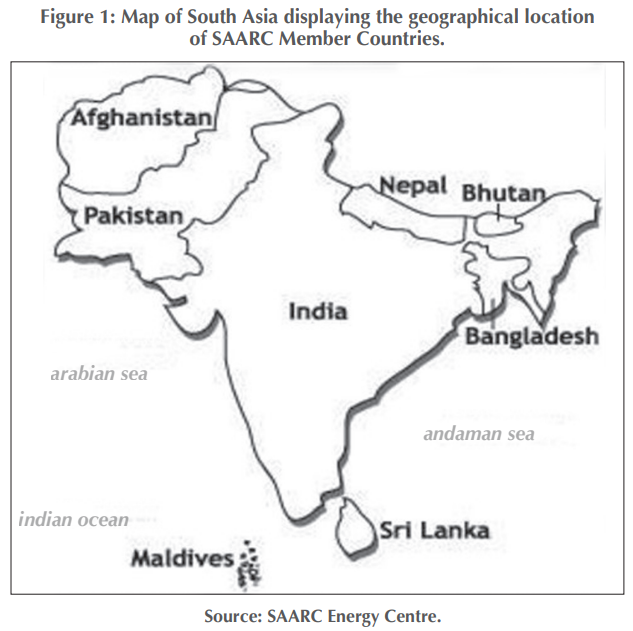

1India is older than South Asia. The Indus Valley civilization, from which India got its name is definitely more ancient than the idea of South Asia, which was strategically invented by the colonial powers to fulfil their military requirements through the compartmentalization of physical geographies. Still, the term “South Asia” became quite popular among the leaders of the post-colonial and never-colonized countries in the vicinity of India. After the United Nations (UN) realized the importance of regional organization and with the establishment and success of the European Union (EU), different regions across the globe were inspired and encouraged by the spirit of regionalism. India’s neighbours felt the same. It was the president of Bangladesh Ziaur Rahman who floated a concrete proposal for establishing a framework for regional cooperation in South Asia on May 2, 1980. Before Ziaur Rahman’s proposal, the need for South Asian regional cooperation was also discussed at the Asian Relations Conference in New Delhi in 1947, the Baguio Conference in the Philippines in May 1950, and the Colombo Powers Conference in April 1954. The establishment and evolution of the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) further motivated South Asian leaders. During his visit to India in 1977, Ziaur Rahman proposed a South Asian regional cooperation framework with India’s Prime Minister Morarji Desai. In the same year, King Birendra Bir Bikram Shah Dev called for regional cooperation among the South Asian countries, while delivering an inaugural speech at the meeting of the Colombo Plan Consultative Committee in Kathmandu. After welcoming King Birendra’s call, President Ziaur Rahman also held informal discussions with the South Asian leaders during the Commonwealth Summit in Lusaka in 1979 and the Non-aligned Summit in Havana in 1979. The Bangladeshi president gave a concrete shape to the proposal following his visit to Sri Lanka and meeting the Sri Lankan President J.R. Jayawardene in 1979. Besides the lobbies and parleys, several other factors also influenced the interest and zeal to establish the South Asian regional organization. While the balance of payment crisis faced by the South Asian countries was further worsened by the oil crisis of 1979, the failure of the North-South dialogue impelled them to constitute a regional entity. Ziaur Rahman himself was eyeing Indian backup to legitimize his coup. The visit of United States (US) President Jimmy Carter and British Prime Minister James Callaghan to India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh in 1978 and assured of economic assistance for the multilateral project on water sharing of the Ganges and Brahmaputra also came as the moments of motivation.

2While the proposal from Bangladesh was instantly endorsed by Nepal, Bhutan, Sri Lanka, and Maldives, the two archrivals – India and Pakistan – appeared sceptical. Indian policymakers feared that Bangladesh’s proposal may offer an opportunity for the small countries in India’s backyard to gang up against India by regionalizing all the bilateral issues. Pakistan, too, deemed the proposal as the Indian ploy uniting all the South Asian countries against Pakistan and consolidating Indian dominance in the region, both strategically and economically. In the draft paper prepared by Bangladesh after a series of diplomatic consultations at the UN headquarters in 1980, the issues sensitive to India and Pakistan were dropped and prioritized only on non-political issues and noncontroversial areas for cooperation. From August 1-3, 1983, the first South Asian foreign minister’s conference was held in New Delhi that discussed an Integrated Program of Action (IPA) on mutually agreed areas of cooperation (i.e., agriculture, rural development, telecommunication, metrology, health and population control, transport, sports, arts and culture, postal services, and scientific and technical cooperation). They also adopted a declaration on regional cooperation, formally beginning an organization known as South Asian Regional Cooperation (SAARC). The main objectives of the Association, as defined in the charter, are: to promote the welfare of the people of South Asia and to improve their quality of life, to accelerate economic growth, social progress, and cultural development in the region, to provide all individuals the opportunity to live in dignity and to realize their full potential, to promote and strengthen collective self-reliance among the countries of South Asia, to contribute mutual trust, understanding, and appreciation of one another problem, and to promote active collaboration and mutual assistance in the economic social cultural, technical and scientific fields.

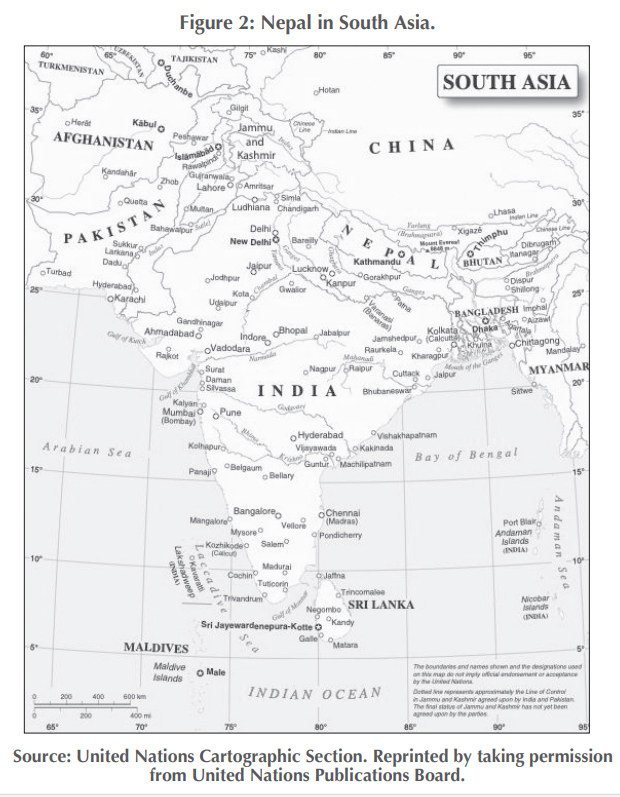

3As one of the founding members of SAARC, Nepal – landlocked between China and India – played an important role in establishing and evolving the organization. Not only during its inception but also at different summits. In 1977, Nepal’s King Birendra addressed the 26th Colombo Plan Consultative Meeting in Kathmandu and emphasized the importance of drawing the mutual benefits from the South Asian water resources. His role was also instrumental in establishing SAARC Secretariat in Kathmandu in 1987. SAARC Tuberculosis Center and SAARC Information Center were also established in Nepal. Nepal also lobbied to make China an observer state in SAARC in 2005, not only to draw reap the economic benefits from the rise of China but also to balance Indian influence in SAARC. Although King Gyanendra formally called for China’s membership, the proposal couldn’t be materialized due to a lack of required consensus. Even after the fall of the monarchy, Nepal continued with the idea of bringing China on board. While Nepal was making preparations for the 18th SAARC Summit which was scheduled to be held in Kathmandu in 2014, Nepal’s Foreign Minister Mahendra Bahadur Pandey and Finance Minister Ram Sharan Mahat were heard of making China a full-fledged member of SAARC. Nepal has been raising this issue in several official negotiations as the Chair of SAARC since 2014. Although India’s priority has shifted from SAARC to the Bay of Bengal Initiatives for Multisectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation (BIMSTEC), Kathmandu has denuded the revival of SAARC and intends to draw benefits from both forums.

4Still, the hope and aspirations of the landlocked countries in regard to connectivity and interdependence have been jeopardized amidst the foreign policy securitization of the regional powers and great powers. After all, India’s response to South Asian regionalism is driven by two factors: isolating Pakistan and containing China. Concurrently, Beijing and Washington intend to lure the South Asian countries through aid and assistance. Consequently, the strategic interest of the great powers in the region has impacted the objectives, structure, and activities of the regional entity.

5Upon the same realization, this study intends to highlight the small state’s perspective towards South Asian regionalism by situating the case of Nepal’s approach to the same. Despite being the incumbent chair of the regional organization, Nepal does not have the capability to propel SAARC ahead. For that, however, not only Nepal’s small state syndrome is to be blamed but a varying degree of great power contestations in the region should also be analysed. As Nepal’s small states syndrome emanates predominantly from its geostrategic location.

SAARC: Evolution, Structure, and Activities

6On March 15, 2020, SAARC leaders participated in a video conference proposed by the Prime Minister of India Narendra Modi to contain the spread of the COVID-19 Pandemic. While Modi and other South Asian leaders emphasized the need for coordinated efforts to prevent the spread of COVID in the region, the need for coordinated and collective efforts in resolving the common problems of the region was realized decades before this specific event that once again brought South Asian leaders together digitally during the first wave of the global pandemic. Like all the regions around the world, South Asia was also heavily impacted by the pandemic. No unified and coordinated moves could be made to prevent the spread of the pandemic. SAARC Charter’s commitment to promoting stability and peace, social justice, and economic prosperity had to compromise against the pandemic and the need for joint action and enhanced cooperation, as envisioned in the charter, could not be materialized. Yet, the lack of a coordinated approach in SAARC was not exceptional only during the pandemic.

7Historically, tensions between India and Pakistan have impacted SAARC’s objectives, charter, and principles. The rise of China and its entry into SAARC has increased India’s anxiety towards the regional body, dissuading the probability of revitalizing the organization. The advancement of Indo-US strategic partnerships in the context of containing the rise of China has paralyzed and polarized the entire project of South Asian regionalism.

8South Asian regionalism has endured the narratives built on statements as Asian Regionalism has failed: SAARC is in “coma”; BIMSTEC is promising and hopeful; ASEAN is comparatively successful; BIMSTEC bridges SAARC and ASEAN; Resurgent Asia is possible through regionalism and Connectivity; Post-Brexit has evolved Asian regionalism under the purview of Sino-US contestations. While the traditional approach to regionalism concentrated on how the participating states share geographicaproximity and sociocultural homogeneity shaped by the shared linguistic, civilizational, and historical heritages and a certain degree of reciprocity.

9The constructivist approach to regionalism reckons region as a socio-political construction through the use of numerous concepts and metaphors. To Amitav Acharya, a region is always constructed, whose norms, identity, and meaning may change over time. While talking about South Asian regionalism, we also need to heed that regions are varied in terms of their identity, membership, institutional values, and scope. The pronounced differences between regionalism in Europe and Asia are an apt example. While regionalism in Europe has evolved under the purview of formal bureaucratic-legalistic institutions, Asian regionalism appears more informal, less legalistic, and consensus-driven. Informal agreements and strong adherence to the spirit of non-interference characterize Asian regionalism. Despite having an extensive set of institutions, they are not robust and resilient owing to the limited resources of the Member States and their unending reluctance in accepting the usurpation of sovereignty.

10The traditional approach to regionalism assumes that states have a degree of mutual interdependence in multidimensional aspects including development and security, as well as on the cultural, linguistic, and historical fronts. Countries located in a particular geographical region find themselves closer owing to their connected history, civilizational affinities, shared development patterns, and security issues. Still, there are several other factors influencing the process of regionalism and integration. Although post-war regionalism – specifically from the 1940s to the 1970s – was replaced by the European model of market-centric regionalism, the security conundrum brought on by internal and external threats remained the key driving force behind regionalism. The desire for collective security and economic aspirations to combat underdevelopment and poverty remained at the heart of Asian and African regionalism.

11While the Bandung Conference, held in Indonesia in 1955, brought together 29 Afro-Asian countries to plan collective resistance against the Cold War bipolarity (Wasi, 2013), the current SAARC members namely India, Pakistan, Nepal, and Afghanistan also took part in the conference and raised their voice for Asian unity. These countries echoed their desire to maintain their national security and advance their socioeconomic status through mutual collaboration and cooperation (Haider, 2001). They acknowledged the process of regional integration as unavoidable firstly for the promotion of stability, prosperity, and cooperation among the countries, and secondly, for collectively resisting the influence of external power and bloc politics. Consequently, the establishment of SAARC became a necessity demonstrating not only “growing interdependence among developing nations” (Haider, 2001), but most importantly, inspired by the EU and the ASEAN.

Path Dependency in SAARC

12Path dependence in SAARC commenced with its conception from 1977- 1980, which was followed by meetings of the SAARC countries’ Foreign Secretaries from 1981 to 1983 and 1983 to 1985, and summits. In other words, they are the four stages enouncing the evolution of SAARC (Iqbal, 2006). While the roles of the leaders of the Member States were instrumental in the establishment of SAARC, the inception of the organization is largely attributed to the efforts of Zia-Ur-Rehman who called for a summit of seven countries (Nepal, India, Bhutan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Maldives, and Pakistan) in 1980 to promote a functioning regional organization. India and Pakistan held initial reservations (Haider, 2001), but the negotiation bore some fruit as the organization came into practice five years later in 1985.

13The establishment of SAARC in December 1985 was seen as a crucial turning juncture in South Asia’s history. It set the ground for upcoming initiatives to support regional economic development and collaboration and signalled the start of a new era of cooperation and integration. Leaders of the seven countries adopted the SAARC charter at the Dhaka summit in 1985, namely Hussain Muhammad Ershad from Bangladesh, Jigme Singye Wangchuck from Bhutan, Rajiv Gandhi of India, Maumoon Abdul Gayoom of Maldives, Birendra Bir Bikram Shah Dev of Nepal, Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq of Pakistan, and J. R. Jayewardene from Sri Lanka. In April 2007, Afghanistan joined the organization. Afghanistan had submitted a proposal to join the group in 2005, and it was accepted during the 14th SAARC summit, which took place in New Delhi, India, in April 2007. Today, SAARC comprises eight independent sovereign nation-states, namely Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Nepal, Sri Lanka, and Maldives.

14Despite its Cold War legacy and its Member States’ commitments on the papers, South Asia has traditionally been one of the world’s least economically integrated regions, with low levels of trade and investment amongst its members. Although the primary motivation for the establishment of SAARC was its Member States’ desire to accelerate regional economic development by attaining enhanced prosperity and development, the teleological approach to regional organizations (which compares the objectives of the regional entity with its achievements and accomplishment) attests the convergence between what is in the papers, plans, and principles, and what is being practiced. Two landlocked countries – Nepal and Bhutan – are unprecedently dependent on India. Sri Lanka and Bangladesh also find it easier to trade with India owing to their geographical proximity. Pakistan desires to satisfy its ego by not trading with India. The respective economy of Afghanistan and Maldives has been impacted by terrorism and climate change. And when China had accumulated the will and energy to substantially replace the dominance of the Indian market and investment in the region, New Delhi found refuge in the strategic partnership with the US.

15Notwithstanding the geopolitical tensions riveting SAARC, numerous endeavours and agreements have been made with attempts to promote regional interactions. Following the adoption of the ‘Dhaka Declaration’ at the inaugural summit meeting of South Asian leaders (SAARC, 1985), the organization took measures to tackle regional problems by establishing a permanent secretariat in Kathmandu (SAARC, 1986) and a regional food reserve to abolish poverty and hunger (SAARC, 1987). Several agreements and initiatives were proposed and adopted at subsequent summits, such as the SAARC Regional Convention on the Suppression of Terrorism, the SAARC Regional Fund (SAARC, 1990), and the SAARC Preferential Trading Arrangement (SAPTA), which exchanges tariff concessions, was proposed in Colombo with the aim of fostering and preserving reciprocal trade and economic cooperation within the region (Department of Commerce, 2023). SAARC Development Fund (SAARC, 1995) SAARC Documentation Center in New Delhi, and SAARC Meteorological Research Center in Dhaka (SAARC, 1995) were established. The agreement to establish the SAARC Food Bank was signed by its members at the 14th SAARC Summit. The Food Bank aimed to support regional populations’ access to food through national initiatives (Department of Food and Public Distribution, 2023).

16Moreover, when India’s Prime Minister Manmohan Singh mooted the idea of establishing a regional university in 2005, the regional intergovernmental agreement was finally signed at the 14th SAARC summit (SAARC, 2006). At the 15th SAARC Summit on August 3, 2008, the leaders signed a charter for the SAARC Development Fund (SDF) (SAARC, 2008). Sri Lanka had proposed the SAARC Preferential Trading Arrangement (SAPTA) at the sixth SAARC summit in Colombo in December 1991, with the objective of enhancing and preserving mutual trade and economic cooperation within the SAARC area through the exchange of tariff concessions (Department of Commerce, 2023). At the seventh SAARC summit, the SAPTA framework was finalized (SAARC, 1993). Though SAPTA was officially signed on April 11, 1993, and the agreement came into force on December 7, 1995 (Chander, 2005). The agreement initially provided for the exchange of tariff concessions on a reciprocal basis among the seven member countries: Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka (SAARC, 1993).

17The most recent development in the evolution of SAPTA is the signing of the Free Trade Area Agreement, which aims to further liberalize trade in the region and increase economic integration (SAARC, 2004). The South Asian Free Trade Agreement (SAFTA) was signed during the 12th SAARC Summit in January 2004 with the intention of gradually lowering and ultimately eliminating away with tariffs on the majority of commodities (Ministry of Commerce and Industry, 2020). SAFTA, which sought to establish a free trade area among the countries of South Asia, was introduced after the Member States took the initial step towards increasing trade among themselves. The agreement also includes guidelines for collaboration in areas including intellectual property, investment, and trade-related technical constraints (Ministry of Commerce and Industry, 2020). Since the agreement came into effect in 2006, the Member States have committed to gradually decreasing tariffs on goods imported from other member countries to a range of 0-5% over a period of 10 years (Chander, 2005). Both SAPTA and SAFTA have played a significant role in the South Asian regional cooperation, nurturing trade, and economic integration.

Crisis in South Asian Regionalism

18Despite its set goal to enhance people’s quality of life in South Asia by accelerating economic, social, and cultural advancement, and by encouraging collective self-reliance among South Asian countries to advance people’s welfare primarily (SAARC, 2020), the 38-year-old regional organization has been impaired and dwarfed in its own doldrums as summits have been halted since 2014 (Lama, 2019). The impacts of not having regular summits are further realized with the incumbent SAARC Chair Nepal’s inability to propose the regular sessions of the SAARC Council of Ministers, which had been previously held on the sidelines of the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) (Giri, 2021). As a result, the programming committees remain uncertain regarding how to proceed ahead, further attesting that South Asia is the least integrated region of the world.

19While the SAARC has been long battling an internal crisis (Mahmood, 2000), the unending rivalry between India and Pakistan, Sino-Indian contestations, and Sino-US geopolitical conflict have polarized the agendas, issues, and interests of the Member States. If the India-Pakistan rivalry divulges the divergence of the decisive forces, the engagement of the US and China with the SAARC countries through aid and assistance is either interpreted from the perspectives of external actors or a “new cold war”.

20Many saw Narendra Modi’s visit to Bhutan and Nepal, shortly after he was elected prime minister in 2014, as a rebirth of the “Gujral Doctrine” (a set of five principles on India’s neighbourhood policy introduced by India’s Prime Minister I.K. Gujral), and there were many reasons for optimism when he addressed his country on August 15 from the Red Fort, emphasizing regional cooperation (Modi, 2014). He also invited all the heads of the Governments of South Asian countries to attend his first swearing-in ceremony as the Prime minister (Swami, 2014). When Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Shariff joined the oath-taking ceremony of the Indian Prime Minister, many perceived the event as an ice breaker in cooling down the situation in South Asia (Sardar and Malik, 2014). Speculations were rife on Modi’s leadership and hopes for the revitalization of the regional entity was generated, particularly after Modi’s visit to Pakistan in 2015 to meet Shariff, that laid grounds for the rejuvenation of the regional entity. But things started to go wrong after the Uri attack of 2016 (Sahoo, 2019).

21After the success of the 18th SAARC summit in Kathmandu, where both Modi and Shariff had signalled their efforts in reinvigorating SAARC by shaking hands with each other, the 19th Summit was scheduled to take place in Islamabad in 2016. But India unilaterally cancelled the event after the 2016 Uri incident. Later, Bhutan, Sri Lanka, and Afghanistan followed suit (Chaudhury, 2022). After India refused to take part blaming a Pakistan-based terrorist group for enticing violence and death, the scheduled SAARC summit has been indefinitely suspended. While the two nuclear-armed countries make up most of the area’s land mass and account for more than 75% of the region’s people, it should come as no surprise that the conflict between India and Pakistan is the main factor impeding regional integration.

22The India-Pakistan divergence in South Asian regionalism is not a new phenomenon, however, which all began with the scar of partition in 1947 and the emergence of Bangladesh in 1971. Episodes of wars and Kashmir issues have always halted any attempts towards rapprochement (Hiro, 2015). The situation became worse after the border skirmishes of 2019, which were followed by the exchange of a series of airstrikes into one another’s territory. Pakistan was disillusioned after India revoked Article 370 abolishing the special status of Jammu and Kashmir. To Pakistan, it was an ‘illegal act’ of India (Choudhury, 2019).

23While a country’s foreign policy is an extension of its domestic politics, India’s approach to South Asian regionalism under the leadership of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) offers an apt example. After BJP came to power in 2014, only one SAARC summit has taken place. Even more intriguing is BJP’s 2019 election manifesto, which explicitly mentioned promoting regional cooperation by isolating Pakistan through the Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, and Nepal (BBIN) Initiative and BIMSTEC instead of continuing with SAARC or even considering it a regional integration forum (Bharatiya Janata Party, 2019). Since none of the summits and other usual meetings are being conducted, SAARC has been in “coma”.

Two Aspects of South Asia

24In the past, links between peoples, traditional state systems, and other political communities were limited to the regional level. But the advancement of technological growth, which has helped countries to project their relationships beyond small geographical borders, has also helped countries to expand beyond limited geographical boundaries. The ontological approach to defining a region is based on identifying regions, where countries discover some form of linkages between governments and peoples in regard to the spheres of economics, security, religion, or culture. Regionalism is a phenomenon that emerged basically after two types of waves.

25irstly, the establishment of regional organizations, such as the EU after World War II, became possible only once European states began to feel more comfortable and privileged cooperating rather than competing. Secondly, the need for market integration aimed at distributing economic gains inspired regional organizations to try their luck, but most of them except the EU have not succeeded. A preferential approach was also initiated to serve the interest of the regions. Still, the most important characteristic of a region is based on its civilizational affinity and geographical proximity, which connects the dots of cultural chemistry (Karns et. al., 2015). However, that may not always suffice for a region to stand together. Strengthening the institutional values, enhancing the organizational structure, and routinely sustaining the activities for path dependency is of utmost importance, which is still missing in South Asian regionalism which reduces it to the least intergraded region of the world. In South East Asia, regional trade among the countries accounts for 50% percent, while it stands only at five percent in the South Asian region (World Bank, 2022), which is largely caused by trust deficit between the member countries, lack of political consensus, and high transportation cost,

26Primarily, the focus of South Asian regionalism centred on addressing regional issues including poverty, poor health, and underdevelopment (SAARC, 2020). Although the regional body’s scope expanded to address new and intricate issues including emerging health issues like the COVID-19 pandemic, climate urgency, terrorism threats, and illegal immigration, which demand a serious commitment from all members of the group, the trust deficit between the Member States have offered fewer opportunities for cooperation. Despite the member countries’ readiness, both on the papers and policies, in implementing numerous bilateral and multilateral free trade agreements (FTAs), there exists a gap in the implementation through the foreign policy behavior that has made the South Asian region appear so close to the perspective of geographical proximity and homogeneity, yet so far from the viewpoint of institutional values and organizational strength.

27While SAARC’s existing institutional values and organizational behavior have not been able to effectively implement the objectives of the organization, two aspects of South Asia are often unfolded by scholars while examining the geopolitical variables of South Asian regionalism. To them, there are two aspects of South Asia:

-

South Asia with India and Pakistan,

-

South Asia without India and Pakistan.

28The region is already dealing with intra-regional conflicts of religious and political nature, and border issues of India with its immediate neighbors. Small states like Nepal, however, are not in a position to direct the regional entity. Despite being an incumbent chair of the SAARC, policymakers in Kathmandu are as helpless as their South Asian counterparts.

29In such a context, Beijing and the US want to entice the South Asian nations with aid and support, whereas India’s response to regionalism in South Asia is motivated by two factors previously mentioned – isolating Pakistan and containing China. As a result, regionalism in South Asia has been rendered ineffective due to the strategic interests of the great powers that oblige the small countries and the regional powers to serve the interest of the great powers. With this background, this study aims to find out how big power competition in South Asia has incapacitated the region as a whole and its impact on small states of South Asia.

The Sino-Indian Conflict and Global Power Rivalry

30SAARC, as prescribed in its external relations, intends to engage with the nine observer states – Australia, China, the EU, Iran, Japan, Korea, Mauritius, Myanmar, and the US – in the areas of connectivity, communication, agriculture, health, energy, environment, and economic cooperation. While two SAARC archrivals – India and Pakistan – are also the members of Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), the other SAARC countries including Sri Lanka, Nepal, and the Maldives are dialogue partners, and Afghanistan an observer in SCO that is steered by China and Russia. India and Pakistan got membership in SCO in 2017. Although India is riled by the increasing presence of China in South Asia, both of them are together in the association of five regional economies, i.e., Brazil Russia India China, and South Africa (BRICS). As the present article already delved into India’s relations with Pakistan and its impact on SAARC, India-China relations and their impacts on the South Asian region will be now discussed and analyzed.

31In a speech commemorating the first anniversary of India’s constitution, Mao Zedong said that Sino-Indian relations have been characterized by “great friendship” for thousands of years (Government of India, 1962). Before the border Skirmishes of 1962, the popular rhetoric of ‘Hindi-Chini Bhai Bhai’ (Indians and Chinese are brothers) was admired by many. Since then, Sino-Indian relations have passed mostly through different layers of conflicts and at times traversed through the spirit of cooperation as well (Khanal, 2022). Neither geographically nor politically, China does belong to South Asia. Still, South Asian affairs cannot be well comprehended without taking China into account. It is not just because it has borders with five of the eight South Asian nations – Afghanistan, Bhutan, India, Pakistan, and Nepal – but also due to its contemporary position and significance in international affairs. Most significantly, it shares borders with Pakistan and India, two powerful and diametrically opposed forces in South Asian politics (Kumar, 2015). While China’s aspirations, interests, and ambitions to enter South Asia are widely perceptible, New Delhi has reckoned China’s entry into the region as a threat to its traditional sphere of influence on the economic, political, and cultural fronts.

32Since the Dhaka Summit in 2005, China has been an observer state in SAARC (Gancheng, 2012). While Pakistan, Nepal, and Bangladesh welcomed China’s presence in the region, India, Bhutan, Afghanistan, and the Maldives opposed it from the very start (Ganapathy, 2007). China has been collaborating with SAARC countries in several ways. In fact, it has moved closer to its South Asian neighbours because of its determination to establish the China-South Asia Business Forum, which was set up in 2004, and which focuses on communication, cooperation, development, and mutual advantages. To connect Chinese businesses with SAARC Chambers of Commerce and Industry, the China-South Asia Business Council was founded in 2006 (Panda, 2010). China has managed to escort its strategies through cooperation with South Asian countries in recent times too, for example, through the Belt and Road (BRI) Initiative. When Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi proposed the China-South Asia Emergency Supplies Reserve and Poverty Alleviation and Cooperative Development Center in 2021, it garnered wider attention and was participated by Foreign Ministers from Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka (Giri, 2021).

33While pressure for spheres of influence is pushing India and China to the toughest times of history, India seems concerned mainly due to a few reasons that might spill out due to Chinese presence in the region. First, although the “Chennai Connect” raised expectations for friendly relations between these two Asian superpowers, the border clash that immediately followed in the Galwan Valley raised doubts about their compatibility. Second, China’s admission into SAARC will undoubtedly lessen India’s strong position in the area, further undermining its interests and complicating SAARC. Third, India has historically perceived Pakistan and China’s “all-weather friend” as a perpetual threat, which could have terrible effects on India’s security concerns. With China is flexing its muscles to engage with South Asian nations, India is increasingly turning away from SAARC in favour of organizations like BIMSTEC and BBIN, which do not include Pakistan. The conflictual relations between them is certainly a worrisome indication of South Asian regionalism which has made the future of SAARC more uncertain.

34In addition to the Sino-Indian contestations and their repercussions on South Asian regionalism, the SAARC region has also endured the implications of the global power rivalry. Strategic regions in the vicinity of Chinese borderlands have turned into the geopolitical radar of the global power race (Manon, 2022). Nepal’s Himalayan borders with China’s Tibetan Autonomous Region (TAR) are extremely securitized in order to prevent the influx of Tibetan refugees from Tibet to Nepal. When the US Army’s Pacific Command Commanding Senior Colonel Charles A. Flynn came to Nepal in March 2023, he expressed his desire to have breakfast in Everest, which was viewed as an act of signalling against China. Thus, his visit to Everest was politely withdrawn at the last moment. In Nepal, a US-sponsored US$ 500 million grant agreement is perceived as an American ploy against China-led Belt and Road Initiatives, of which Nepal is a member and is presently drawing BRI implementation plans.

35Foreign policy analysts and security analysts perceive the boycott of the 2021 Winter Olympics in China by a US-led group of countries as the start of a “new cold war” that is prompted primarily by the rise of China and its expanding influence throughout the world (Guzman, 2021). The security of the entire region bordering China has been threatened by a major power rivalry because of the US’s divisive conflicts. Earlier in the August of 2022 Nancy Pelosi landed in Taiwan amidst possible retaliation by China (Reuters, 2022). The teasing footprints across Chinese pressure points causing diplomatic embarrassment is being tried by the US frequently, which has led to a trust deficit between the two great powers of the world. Where China seeks to advance into the warm waters of India’s ocean crossing the Himalayas, the US sees this as an opportunity to engage in South Asia as a part of its strategy to block possible routes and gateways of China into the region which has brought triangular competition into the region,

36Under its “One Belt One Road” (OBOR) initiative, China has envisioned a network of logistic corridors for regional economic integration in the region. It has initiated a key project with Pakistan under the OBOR, the so-called China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), which is expected to provide China access to the Indian Ocean via the Gwadar port. The Global Security Initiative (GSI), an idea for security architecture, was developed by the Chinese President and Secretary General of the Chinese Communist Party (CPC) Xi Jinping during the Boao Forum in 2021. Soon after, during the UNGA session, Xi Jinping also proposed the Global Development Initiative (GDI), which aims to implement the 2030 global agenda (The Annapurna Express, 2023). Recently, China has also proposed Global Civilizational Initiatives (GCI) with the intention to lure more states in South Asia and beyond, particularly those with which China shares a connected history.

37Concurrently, alliances are being created to restrain China in the Asia Pacific region as both China and the US seek to persuade other countries to work with them. The G7 leaders have envisioned a Build Back Better World (B3W) plan to oppose China’s BRI. The Quad countries including US, India, Japan, and Australia intend to contain the rise of China. The Basic Exchange Cooperation Agreement (BECA) between India and the US has identical goals, although different tactics may be used for geospatial intelligence in the Himalayan region. While the US considers India to be an important strategic partner of the Indo-Pacific region to contain China, despite the US’s perception of China-India rivalry as a destabilizing factor, such an equation has geopolitically polarized the South Asian region. Policymakers in India find the alliance advantageous since the power equation is expected to prevent Chinese advancement into the region. However, tensions between China and the US and China and India have opened the vistas of opportunities to revitalize and strengthen Sino-Pakistan relations. As such, South Asia has become a geopolitical flashpoint because of two important South Asian countries playing a geopolitical game with global competitors derailing possibilities of regional integration in South Asia,

38More than its economic potentialities, the geopolitical component of the region has made it discernible in global politics from the end of the 20th century to today’s 21st century (Lewis, 2006). Despite early doubts and dilemmas of going for integration, the basis of the inception of SAARC was solely for mutual assistance among South Asian Countries (SAARC Charter, 1985). For every country, regional cooperation entails collaboration across governments in the same region to accomplish objectives that are beyond the scope of individual national attainment (Karns et. al., 2015). According to Keohane, the World System Theory method of examining state actions in foreign policy has found four fundamental characteristics of the states, namely the system determining, system influencing, system affecting, and system ineffectual states (Keohane, 1969). States with little influence face structural scarcity mainly on the institutional level which ultimately hampers in their ability to effectively manoeuvre decisions regarding foreign policy for tangible results (Neumann and Gstohl, 2006). Therefore, for small countries to navigate international affairs and build collective self-reliance, multilateral and regional forums are essential. Today’s multilateral system suggests that it provides a platform for small states to act internationally and wield influence. Small states have accommodated themselves in several regional and international contexts and, at present, participate in many multilateral forums on a global scale. It is said that being a member of these organizations boosts foreign policy confidence and assertion on the part of small states (Sens, 1993). While the summits and sideline meetings have been halted for years, there is now a definite question of how much the small states in South Asia have managed to garner the benefits of South Asian regionalism, mainly the SAARC, or have they fallen in the grave of trilateral geopolitical contestation. This seeks serious scrutiny. Understanding Nepal’s endeavours and approaches in SAARC may be methodologically advantageous in drawing answers to that enquiry.

Neighbourhood and Regional Cooperation in Nepal’s Foreign Policy

39As a founding member and current Chair of SAARC, Nepal staunchly advocates for regional cooperation as a means to advance the collective welfare of South Asia. It represents the hope of over 1.7 billion people for this region for accelerated economic growth, social progress, and cultural development (SAARC, 2020). As such, Nepal “eagerly look[s] forward to handing over the Chairmanship… and SAARC Member States will come up with a consensus to convene the Nineteenth SAARC Summit at an early date” (SAARC, 2020).

40As a country that has consistently supported strong South Asian ties among its neighbouring states, Nepal confronts double-edged pressure on both fronts, domestic and international affairs. On the one hand, structural scarcity makes it difficult for a country to internationalize its foreign policy but on the other hand, the state and its sovereignty are vulnerable to external pressure, particularly from its two powerful neighbours, China and India (Dixit, 2014).

41The Doklam standoff of 2017 between India and China had nearly tested Nepal’s conventional survival strategy while almost compelling to take either side of her immediate neighbours. In 2015, when India imposed an unofficial blockade on Nepal, China exhibited the gesture of rescue to the landlocked Nepal by sending oil via the serpentine and hostile route. The Chinese oil stopped coming to Nepal once the blockade came to an end (Deutsche Welle, 2015). Nepal also went on to sign the Trade and Transit Agreement with China in 2016 (The Himalayan Times, 2016). While India has always expressed its disagreement over CPEC, the trade and transit agreement between Nepal and China haunted Indian decision-makers. While Indian security analysts branded Nepal as the satellite state of China, Chinese foreign policy experts branded the China-led BRI as the strategic gateway to enter South Asia. New Delhi saw it as a breach of its conventional sphere of influence (Upadhyaya, 2022).

42To India, South Asia is its traditional sphere of influence. To China, South Asia is a new market created by immense demography. It is where the threat to Indian economic nationalism lies. Chinese investment in Nepal’s hydropower was perceived by Indian policymakers as harm to India’s strategic and economic concerns. India’s bordering regions with Nepal, including Uttar-Pradesh, Bihar, Uttarakhand, and West Bengal have been facing problems of power outages and are eager to buy electricity from Nepal. Despite the power deficiency, Indian policymakers made a reactive statement that New Delhi will not buy electricity built with the investment of the Chinese companies in Nepal’s hydro. Some Indian officials allegedly stated that “We cannot afford to buy power from a Chinese firm while our troops are dying on the frontiers” (Shrestha, 2022). With the change of government in Nepal, New Delhi managed to replace Chinese firms from the major hydropower stations and expressed its readiness to buy electricity from Nepal.

43Although SAARC has identified energy infrastructure as of fundamental importance in regional development, Nepal’s helplessness divulges how the impact of geopolitical contestations has not only paralyzed the country’s search for prosperity through transit diplomacy but also jeopardized the dream of freeing entire South Asia from the problem of the power outage and boost up its industrialization through the use of clean energy.

44Nepal’s impuissance was also noticeable in the recent visit of Nepal’s Prime Minister Pushpa Kamal Dahal to India. Dahal focused more on the discourses, statements, and speeches related to connectivity, infrastructure, and energy development cooperation between Nepal, India, and Bangladesh rather than the long-standing political issues between Nepal and India. The 25-year-old energy agreement demanded by Nepal, the aerial route from Mahendranagar at an altitude of more than 30,000 feet, and exporting of electricity to Bangladesh were not agreed upon or signed. However, Indian Prime Minister Modi, as reported, has made a verbal announcement to import 10,000 megawatts of electricity from Nepal in 10 years, which is more of a compromise in Nepal’s hydro sector.

45Nepali water resources being handed over to an Indian company without competition is risky. While Indian companies will make the project and earn the main profit, Nepalis will only run the profit. With the Indian monopoly over Nepal’s hydropower, Nepal will become more dependent instead of being self-reliant. Moreover, India has not made a declared policy for electricity projects built on third-country companies’ investments in Nepal. Instead, India’s undeclared policy of prohibiting electricity from such projects has baffled Nepali policymakers and development planners, which is also not healthy and beneficial from the perspective of South Asian regionalism. Precisely, it is against the spirit of regionalism. It should be understood in the context of the Adani-Modi ties that have influenced the fate of India’s ports, power plants, electricity, airports, solar panels, cement, coal mines, and TV news channel. Representatives of Adani groups have been visiting Nepal since 2022 and meeting high-level officials from the office of the PM, the National Planning Commission, the Investment Board Nepal, the Ministry of Energy, and the Nepal Electricity Authority. Adani Group has expressed its interest in the 10,000-Megawatt Karnali Chisapani project. While India emphasized the continuation of what was agreed in the past, PM Dahal appeared more submissive. While PM’s visit was not well planned and agendas were not systematically presented, it manifested Nepal’s small state syndrome.

46Although Nepal has been demanding the air route to operate the Bhairahawa airport, PM could not persuade the Indian side, citing Nepal’s rights and international aviation laws. After all, Bhairahawa airport helps a lot in boosting the tourism sector that has been paralyzed by the COVID-19 pandemic. As much as Nepal is excited to sell electricity, Bangladesh is willing, while India is progressing on facilitation. But no decisive dialogue between these three countries has taken place. This visit was also limited to discourse and statements. On the issue of connectivity too, instead of providing additional air routes to Nepal, India has pledged Nepal to offer its inland waterways for transportation. It cannot be considered natural for an emerging power like India, whose rise needs to be more responsible and accommodative to the legitimate interests and rights of the neighbouring countries. It also tests Nepal’s diplomatic skills and Indian spirit.

47Although the agreements on cross-border digital payments may sound convenient for the people of both countries and definitely an inspiration at the regional level, what cannot be still dismissed is the importance of literacy and privacy issues attached to the mechanism. While Nepal Clearing House Limited and the National Payment Corporation of India have been given the responsibility, banking, and telecommunication hurdles are yet to be removed to materialize the entire process. While inching the agreement, the two sides paid no heed to the concerns of Nepali banks, individuals, and financial institutions which have been holding INR 7 billion of the banned notes following the demonetization policy of India. On the issue of borders, no directives were issued by the PM-level talks to the existing foreign secretary-level mechanisms and committees on resolving the existing border problems between Nepal and India in Susta and Lipulekh-Kalapani areas. In 2014, the foreign secretary-level system was given responsibility for resolving the border problems, but no progress has been made. Also, the PM was not able to gather confidence and assertion in discussing the EPG which has recommended the revision of the 1950 treaty between Nepal and India. Nevertheless, Dahal managed to share with the Nepali media on June 2, 2023 (the third day of his visit) in New Delhi that when he raised the issue of Kalapani with Modi, the latter pledged him to find a resolution soon through negotiations.

48The rationale for situating the case of the recent visit of Nepal’s PM to India is to depict how bilateral issues have surpassed the regional issues and even the agendas of energy, connectivity, and transportation have to undergo bureaucratization and securitization of bilateral relations. Dialogue at the PM level is a rare case. In those moments, they should express their ability to materialize this political opportunity and shape the agendas accordingly for the benefit of regional development and regional connectivity. But what will be the future of South Asian regionalism if one neighbour restricts the air route of the other? How will regionalism thrive if one neighbour prioritizes only its own investors and markets? Until when a country has to be submissive to the interest of the great and emerging powers?

49While China reckons that the US misquoted its BRI as a debt trap, Beijing believes that the US engaged in “coercive diplomacy” when Nepali political parties were split into two sides in regard to whether US-funded Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) projects should be endorsed from the parliament or not. While both BRI and MCC projects are expected to ease Nepal’s landlocked misery via connectivity and construction of energy infrastructure, the global power rivalry existing between these countries has put Nepal in a situation of catch-22. Neumann and Gstohl (2006) argue that the institutional laggard usually operational in the small states contributes to big powers contesting against each other. China and the US intending to lure Nepal with their aid pledges and assistance has manifested Nepal as the hotspot of global power rivalry. Nepal’s case represents how a state entrapped between the Sino-Indian, Indo-Pakistan, and Sino-US contestations has to endure policy limitations upon its desire to grow and expand its multifaceted links within and beyond South Asian regionalism.

Conclusion

50This exploratory study has realized that SAARC as a regional forum has failed to attain its objectives. Teleologically speaking, despite the numerous agreements signed and institutional mechanisms envisioned, they have not been sufficiently and effectively implemented. While the lack of trust between the two archrival states – India and Pakistan – have made the regional entity helpless, the idea of replacing SAARC with BIMSTEC has gained momentum among Indian policymakers. This assertion’s sole basis is driven by the 38-year-old regional forum’s slow growth, which has been further impeded by the geopolitical rivalry between major powers in and outside the region. While it is proven that geographical proximity alone is not sufficient but is only a necessary condition for regionalism, it also faces some other laggards, and addressing them could prove as an ice breaker in the revival of snail-paced South Asian regional organization. Still, efforts geared by the region’s small states are either swiftly ignored or never receive enough attention until backed up by the policymakers in New Delhi. India’s decisive clout over SAARC has been magnified owing to its centrality in South Asian affairs, the diminishing influence of Pakistan, and above all the Indo-US strategic partnership to contain the rise of China.

51Additionally, exaggerations of geo-political conflicts have regularly disrupted regional integration in South Asia, yet there are either no or very few proposals for resurrecting the SAARC and identifying niches of its rebirth from the perspective of existing agencies and funds. For instance, geopolitical hyperbole has never kept the people of this region at its core and has completely eclipsed the non-state actors and civil societies. While India is connected to all the South Asian countries in terms of people-to-people contact, market, finance, culture, food, and language, other South Asian countries are relatively separated. As such, SAARC is jailed to the values of Old Regionalism, characterized alone by geographical proximity and cultural homogeneity. The operational and pragmatic hallmarks of New Regionalism – people, culture, market, civil societies, International Non-Governmental Organizations (INGOs), and finance – are noticeably absent in South Asian regionalism. As a result, South Asian regionalism is a top-down regionalism, not a bottom-up one. Still, who is benefitting from South Asian disenchantment deserves serious scrutiny. While it seems that the handful of business elites – handpicked by political leaders – do find ‘New Regionalism’ an advantageous affair in their nexus with politicians, the political elites find ‘Old Regionalism’ a lucrative business. As such, the idea of New Regionalism’ appears more extractive in the South Asian context. Modi- Adani nexus is an apt example. Such nexus pays more heed to the profits made by the energy infrastructures and connectivity projects than to the climate urgency of South Asia triggered by escalating flooding occurrences, melting of glaciers, rising sea level, and depleting water and natural resources.

52Therefore, in the wake of shifting geopolitical radar under the purview of the ‘new cold war’, hurdling blames on the state actors more at the geopolitical fronts may relinquish the tragic realities people have lived every day under the shadows of climate urgency, the threat of terrorism and other transnational crimes, hunger, poverty, and underdevelopment. Hence, while mapping the successes and failures of SAARC, the geopolitical lens alone is not sufficient, pertinent, and convincing while the everyday lived experiences of South Asians appear very different.

Bibliographie

Chander Rajiv K., ‘Regional Economic Co-operation in SAARC’, Kathmandu, Nepal Rastra Bank, 2005, pp. 1-41.

Chaudhury Dipanjan R., ‘No Consensus on holding the SAARC Summit: India’, India Times, 7 January 2022. https://economictimes.indiatimes. com/news/india/no-consensus-on-holding-saarc-summit-india/ articleshow/88747272.cms (accessed 20 January 2023).

Choudhury Saheli R., ‘Pakistan reacts to India’s revoking of Kashmir’s special status amid rising tensions’, CNBC, 6 August 2019. https://www. cnbc.com/2019/08/06/pakistan-says-india-move-to-revoke-kashmirsspecial-status-illegal.html (accessed 14 January 2023),

Department of Food and Public Distribution, ‘SAARC Food Bank’, 2023. https://dfpd.gov.in/saarc-food-bank.htm (accessed 11 January 2023).

Deutsche Welle, ‘China to supply fuel to Nepal after India row’, 2015. https://www.dw.com/en/china-to-supply-fuel-to-nepal-after-protesters-block-deliveries-from-india/a18805016#:~:text=Beijing%20is%20 set%20to%20send,key%20border%20crossing%20with%20India (accessed on 25 December 2022),

Dixit Kanak M., ‘Nepal, SAARC, and South Asia’, India International Centre Quarterly, 2014, vol. 41, n° 3/4, pp. 174-182.

Ganapathy Nirmala, ‘Pak, Nepal and B’desh want China in SAARC’, India Times, 6 April 2007. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/ news/politics-and-nation/pak-nepal-and-bdesh-want-china-in-saarc/ articleshow/1863546.cms?from=mdr (accessed 4 January 2023).

Gancheng Zhao, ‘China India Relations and SAARC’, Policy Perspectives, 2012, vol. 9, n° 1, pp. 57-63.

Giri Anil, ‘SAARC meet on UN Assembly sidelines uncertain after Afghan regime change’, Kathmandu Post, 14 September 2021. https://kathmandupost.com/national/2021/09/14/saarc-meet-on-unassembly-sidelines-uncertain-after-afghan-regime-change (accessed 20 December 2022).

Giri Anil, ‘China aims to create an alternative regional bloc in South Asia’, Kathmandu Post, 11 July 2022. https://kathmandupost.com/national/2021/07/11/china-aims-to-create-an-alternative-regional-blocin-south-asia (accessed 15 December 2022).

Government of India, ‘Chinese Aggression in War and Peace: Letters of the Prime Minister of India’, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India, New Delhi, 1962.

Guzman Chad D, ‘How the U.S. Boycott of the Beijing Olympics Is Splitting the World’, Time, 16 December 2021. https://time.com/6129154/ beijing-olympics-boycott/ (accessed on 10 January 2023).

Haider Zaglul, ‘Crises of Regional Cooperation in South Asia’, Security Dialogue, 2001, vol. 32, n° 4, pp. 423-437.

Hiro Deep, The Longest August: The Unflinching Rivalry Between India and Pakistan, New York, Nation Books, 2014.

Iqbal Muhammad J., ‘SAARC: Origin, Growth, Potential and Achievements’, Pakistan Journal of History and Culture, 2006, vol. 17, n° 2, pp. 127-140.

Karns Margaret P., Mingset Karen A., and Stiles Kendall W., International Organizations: The politics and processes of global governance, London, Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2015.

Keohane Robert O., ‘Lilliputians’ Dilemmas: Small States in International Politics’, International Organization, 1969, vol. 23, n° 2, pp. 291-310.

Khanal Gopal, ‘Blending Foreign Policy with Nepal’s Geostrategic Location’, Journal of Foreign Affairs, 2022, vol. 2, n° 1, pp. 121-131.

Kumar Surendra, ‘China’s SAARC Membership: The debate’, International Journal of China Studies, 2015, vol. 6, n° 3, pp. 299-311.

Lama Mahendra P., ‘Lessons to be learnt from SAARC’s Stagnation’, Kathmandu Post, 2 July 2019. https://kathmandupost.com/ columns/2019/06/26/lessons-to-be-learnt-from-saarcs-stagnation (accessed December 08, 2022).

Lewis Jeffrey, ‘Regions Make the World go Around’, International Studies Review, 2006, vol. 8, n° 2, pp. 281-284.

Menon Shivshankar, ‘Keynote Speakers, Prof. Shivshankar Menon, Kantipur Conclave’, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WKKYpy3812E (accessed 8 January 2023).

Ministry of Commerce and Industry, ‘South Asian Free Trade Area’, 2020.

Modi Narendra, ‘PM’s address to the Nation on 68th Independence Day’, 2014. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o1cxHe9TeD8 (accessed 1 January 2022).

Neumann Iver B. and Gstöhl Sieglinde, ‘Introduction: Lilliputians in Gulliver’s world?’, in Ingebritsen Christine, Neumann Iver B., Gstöhl Sieglinde, and Beyer Jessica (eds.), Small States in International Relations, Seattle, University of Washington Press, 2006, pp. 3-36.

Panda Jagannath P., ‘China in SAARC: Evaluating the PRC’s Institutional Engagement and Regional Designs’, China Report, 2010, vol. 46, n° 3, pp. 299-310.

Reuters, ‘Pelosi arrives in Taiwan vowing U.S. commitment; China enraged’, 2 August 2022. https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/ pelosi-expected-arrive-taiwan-tuesday-sources-say-2022-08-02/ (accessed January 13, 2023).

Sahoo Prasanta, ‘India’s Balochistan Tactic: Has it Shattered Pakistan’s Kashmir Dream?’, World Affairs: The Journal of International Issues, 2019, vol. 23, n° 2, pp. 98-115.

Sanjay Kathuria, A Glass Half Full: The Promise of Regional Trade in South Asia, Washington, World Bank, 2018.

Sardar Sheree and Mehreen Zahra-Malik, ‘Nawaz Sharif to attend inauguration of Narendra Modi’, Reuters, 25 May 2014. https://www.reuters. com/article/us-pakistan-india-diplomacy-idINKBN0E402T20140525 (accessed December 12, 2022).

Sens Allen, ‘The Security of Small States in Post-Cold War Europe’, in Haglund David G. (ed.), From Euphoria to Hysteria Western European Security After the Cold War, New York, Routledge, 1993, pp. 134-149.

Shrestha Prithivi M., ‘No China involvement is India’s caveat for buying power from Nepali plants’, Kathmandu Post, 20 January 2022. https:// kathmandupost.com/money/2022/01/20/no-china-involvement-is-india-s-caveat-for-buying-power-from-nepali-plants (accessed 18 December 2023).

South Asian Association for regional Cooperation, ‘Dhaka Declaration’, 1985.

South Asian Association for regional Cooperation, ‘Second SAARC Summit Bangalore Declaration’, 1986.

South Asian Association for regional Cooperation, ‘Kathmandu Declaration’, 1987.

South Asian Association for regional Cooperation, ‘Islamabad Declaration’, 1988.

South Asian Association for regional Cooperation, ‘Male Declaration’, 1990.

South Asian Association for regional Cooperation, ‘Seventh SAARC Summit Dhaka Declaration’, 1993.

South Asian Association for regional Cooperation, ‘Delhi Declaration’, 1995.

South Asian Association for regional Cooperation, ‘Twelfth SAARC Summit Islamabad Declaration’, 2004.

South Asian Association for regional Cooperation, ‘Declaration of the Fourteenth SAARC Summit’, 2006.

South Asian Association for regional Cooperation, ‘Charter of the SAARC Development Fund’, 2008.

South Asian Association for regional Cooperation, ‘About SAARC’, 2020. https://www.saarc-sec.org/index.php/about-saarc/about-saarc (accessed December 28, 2022).

South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation, ‘Visit of the Rt. Hon’ble Mr. K.P. Sharma Oli, Prime Minister of Nepal and Chair of SAARC’, Press release, 3 February 2020. https://www.saarc-sec.org/index.php/ press-release/280-press-release-visit-of-the-rt-hon-ble-mr-k-p-sharmaoli-prime-minister-of-nepal-and-chair-of-saarc (accessed 27 December 2022).

Swami Praveen, ‘In a first, Modi invites SAARC leaders for his swearing-in’, The Indu, 21 May 2014. https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/in-a-first-modi-invites-saarc-leaders-for-his-swearingin/article6033710. ece (accessed 20 December 2022).

The Annapurna Express, ‘China holds first Indian Ocean Region meet with 19 countries without India’, 28 November 2022. https://theannapurnaexpress.com/news/china-holds-first-indian-ocean-region-meet-with19-countries-without-india-34788 (accessed 22 December 2022).

The Annapurna Express, ‘China Seeks Nepal’s Support to promote GSI’, 2 January 2023. https://theannapurnaexpress.com/news/china-seeksnepals-support-to-promote-gsi-36467 (accessed August 16 2023).

The Himalayan Times, ‘Protocol on TTA signed between Nepal and China’, 29 April 2019. https://thehimalayantimes.com/nepal/protocol-on-ttasigned-between-nepal-and-china (accessed 15 January 2023).

Upadhyay Sanjay, ‘Sphere pressure: When Politics Contends with Geopolitics’, Journal of Foreign Affairs, 2022, vol. 2, n° 2, pp. 53-68.

Wasi Nausheen, ‘External Powers and Regional Cooperation’, Pakistan Horizon, 2013, vol. 66, n° 3, pp. 51-61.

White Joshua T., ‘China’s Indian Ocean Ambitions: Investment, Influence and Military Advantage’, 15 June 2020. https://www.brookings.edu/ wp-content/uploads/2020/06/FP_20200615_chinas_indian_ocean_ ambitions_white-1.pdf (accessed 12 January 2023).

World Bank, ‘Regional Trade and Connectivity in South Asia Gets More than $ 1 Billion Boost from World Bank’, Press release, 28 June 2022. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2022/06/28/regional-trade-and-connectivity-in-south-asia-gets-more-than-1-billionboost-from-world-bank (accessed 15 January 2023).

Pour citer cet article

A propos de : Gaurav Bhattarai

Assistant Professor in the Department of International Relations and Diplomacy at Tribhuvan University, Kathmandu, Nepal.

A propos de : Prakash Bista

Master's in International Relations and Diplomacy at Tribhuvan University, Kathmandu, Nepal.