- Portada

- 6/2025 - Multilateral Challenges in an Era of Stra...

- Multilateralism and Liminal Governance: Regional Conflict in Eastern and Central Africa

Vista(s): 324 (5 ULiège)

Descargar(s): 42 (0 ULiège)

Multilateralism and Liminal Governance: Regional Conflict in Eastern and Central Africa

Documento adjunto(s)

Version PDF originaleAbstract

The eastern geographic corridor on both sides of Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) continues to be violent. The DRC, Ugandan, South Sudanese, and Rwandan governments have individually pledged to address this violence, and they have met with more failure than success as both the Allied Democratic Forces (ADF) and the March 23 Movement (M23) terrorize communities, especially in the North Kivu region of the DRC. Where states fail to create stability, multilateral organizations have stepped in. In the case of the DRC, states and other stakeholders, including the contentious participation of the United Nations Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUSCO), have coordinated to resolve the conflict, bringing peacekeepers, as well as financial and material support. Though MONUSCO has struggled to fulfil its mandate, its absence is almost certain to destabilize the region. Multilateral peacekeeping operations, especially those executed by the United Nations (UN), are often blamed for inaction, mandate drift, peacekeeper misconduct, mismanagement and insufficiently funded programs. However, these criticisms against MONUSCO are neither unique to UN missions nor unique to multilateral operations in Africa. While these shortcomings apply here, MONUSCO’s presence in the eastern DRC has generally benefited the region. Multilateral intervention in eastern Congo has brought more accountability, resources, and opportunity than there would be otherwise. Removing multilateral organizations from the DRC promises to cultivate the conditions for corruption, human rights abuses, and national government neglect that invited the violence which made the initial intervention necessary.

Tabla de contenidos

Introduction

1This article inspects criticism of multilateral peacekeeping by using United Nations Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUSCO)’s record in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) as a case study. Multilateralism can be understood as ‘the practice of coordinating national polices in groups of three or more states’ (Keohane, 1990, p. 731) Researchers and skeptics of international organizations, including the foundational work of Barnett and Finnemore (1999), identify a set of bureaucratic pathologies common to those institutions. The research question that this article addresses is: are the problems common to multilateral peacekeeping operations also applicable to the MONUSCO mission in the DRC? Multilateral peacekeeping operations, especially those executed by the United Nations (UN), are often blamed for inaction, mandate drift, peacekeeper misconduct, mismanagement and insufficiently funded programs. The first hypothesis that this article addresses is that each of the problems – described as bureaucratic pathologies - generally attributed to multilateral peacekeeping operations do, in fact, apply to the MONSUCO mission in the DRC. To explore this hypothesis, I employ a case study approach developed by George and Bennett (2005) to posit that MONUSCO is an example of an organization that exhibits these pathologies. However, these criticisms against MONUSCO are neither unique to UN missions nor unique to multilateral operations in Africa (Dijkzeul & Beigbeder 2004; Diel & Druckman, 2010; Dijkzeul & Salmons, 2021). Recognizing that these pathologies exist in MONUSCO aids administrators in improving the mission and does not just fuel reformers’ arguments against that mission. Though MONUSCO’s mission in eastern DRC has come to an end, an analysis of its influence remains important for the future of UN missions.

2 The second hypothesis is that while these bureaucratic pathologies apply here, MONUSCO’s presence in the eastern DRC has generally benefited the region. This assertion is contestable: there is no satisfactory test for a counterfactual situation where a UN mission did not exist in the DRC for the last 25 years. Instead, it is evident that increased instability (in terms of displaced people, neglected security infrastructure, corruption, and human rights abuse) followed MONUSCO’s departure. MONUSCO may have executed its mission with shortcomings – even hurting the people at times it is designed to help - but also provided services to people in eastern Congo provinces that the government has failed to provide historically and has failed to provide in the short period following the MONUSCO withdrawal. Multilateral intervention in eastern Congo has brought accountability and stability (Berkman & Holt, 2006). The methodology to explore this claim is only possible through a qualitative examination of contemporary reports, academic journal articles, and interviews. A systematic analysis of local reports is impossible: the 2021 state of siege declared by the DRC government significantly reduced journalists’ access to reporting on the region, and the national media regulator has restricted reporting on conflict in Eastern Congo (Human Rights Watch, 2024). Likewise, scholarly sources and local accounts cast doubt on statistics reported by government sources (Balingene 2020; Kahombo, Hengelela, & Mabwilo, 2024). Reports by displaced people about the difficulties that they experience lend evidence to support claims in international organization reports and scholarly sources. Anecdotal accounts with locals led the author explore scholarly sources, organizational publications, and local media reports to weigh MONUSCO’s faults against its benefits over its 25-year mandate.

3Populist politicians champion unilateralism, fragmentation, and statism, but MONUSCO provided an element of stability that the DRC government has not achieved. It is fashionable for politicians in less developed states to offer citizens a choice for their national governments’ protection where multilateral institutions operate, but that choice may only shift responsibility to under-resourced local governments and national actors who have failed in the past. The DRC, and other regional states, have a record of failing to provide security or services to rural and marginalized groups. Removing multilateral organizations from the DRC promises to cultivate the conditions for corruption, human rights abuses, and national government neglect that invited the violence which made the initial intervention necessary.

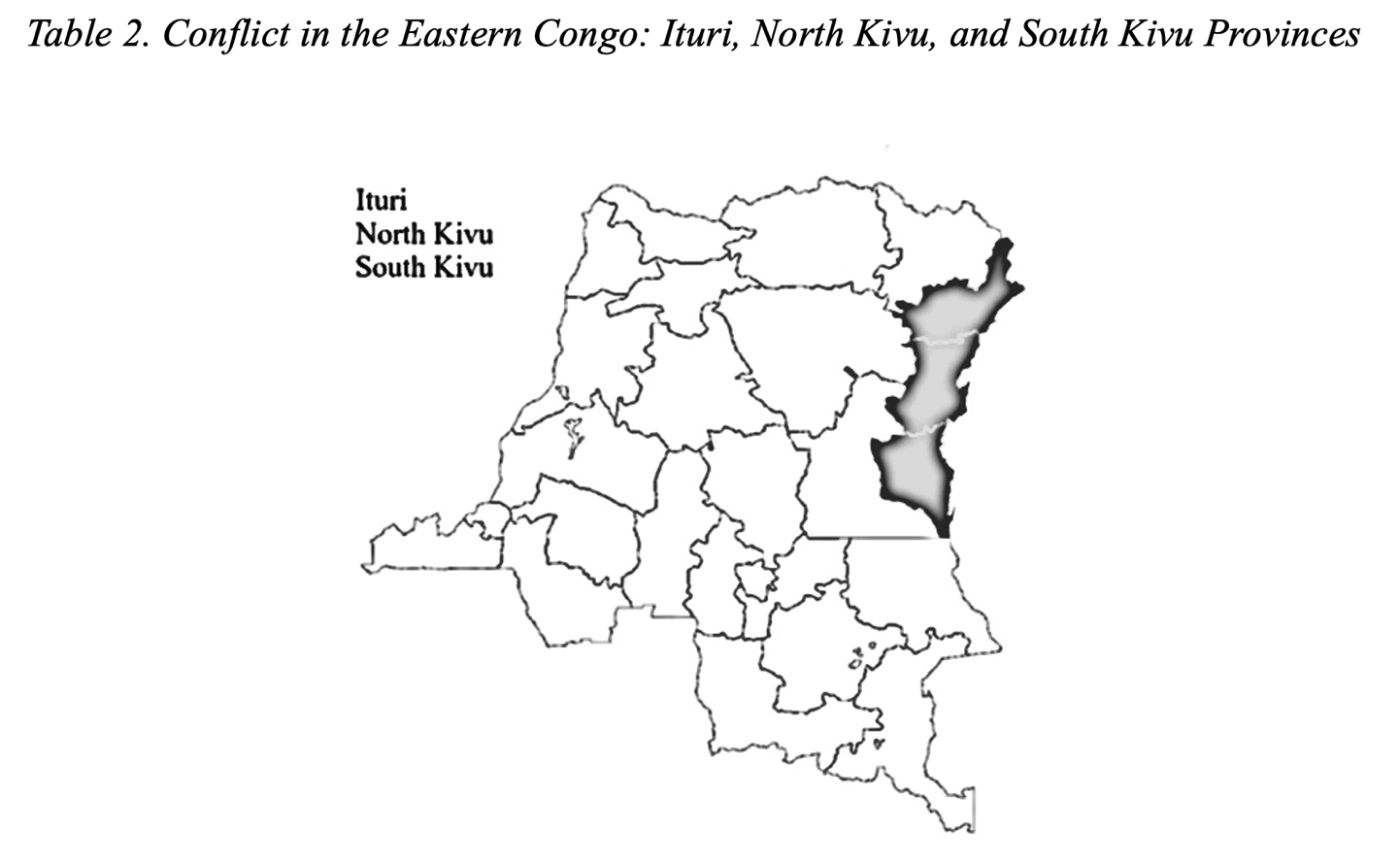

Situational Context

4The eastern geographic corridor of the DRC continues to be violent in modern times. Since the 1990s, the DRC, Ugandan, South Sudanese, and Rwandan governments have individually pledged to address this violence, and they have met with more failure than success as both the Allied Democratic Forces (ADF) and the March 23 Movement (M23) terrorize communities, especially in the North Kivu region of the DRC. Though these two militias are not the only ones controlling territory that borders Rwanda and Uganda, they will be the focus of this paper as they pose the most persistent threat to the three governments, and they also enjoy transnational support.

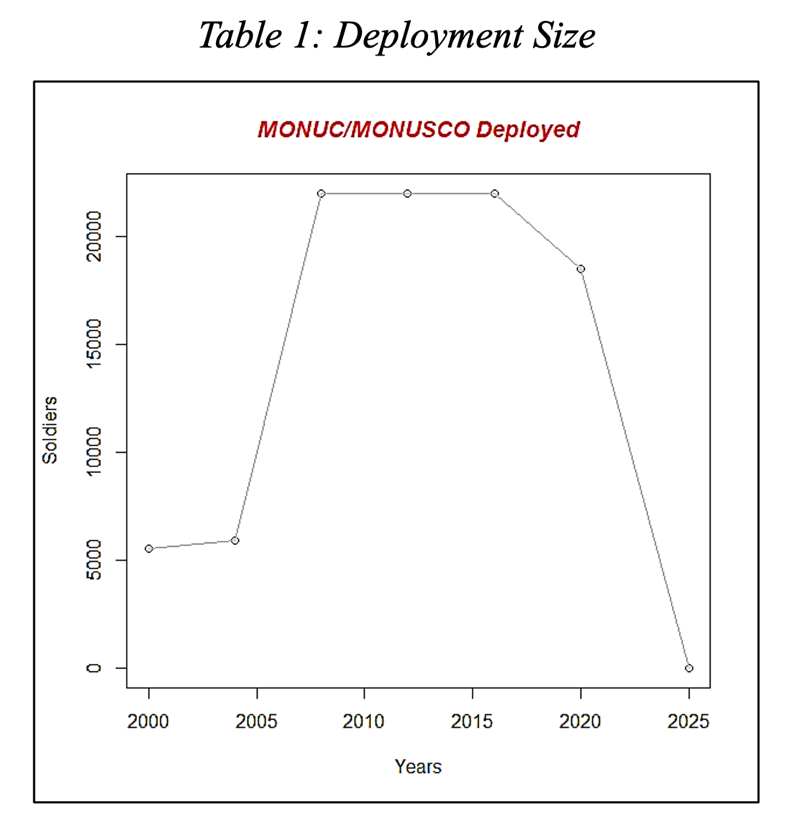

5 Though it enjoys support from the international community, the UN has been unable to guarantee stability in the DRC for the 25 years since it has deployed resources there. The UN is frequently unable to meet local need for security or humanitarian aid, and this shortfall is due to both the overwhelming conditions in the DRC and bureaucratic pathologies within the UN. For context, at its height, the UN has deployed nearly 20,000 soldiers in the region. However, deploying such strong forces into a region of nearly 20 million people is not enough to police or to establish peace in even the most established countries. For reference of scale, domestic police forces in New York City (population of 18.8 million), Tokyo, Delhi, Sao Paul, Mexico City, and Shanghai (UN 2018 estimates) all outnumber the UN security forces in the DRC; the areas within the MONUSCO mandate roughly contain as many people, occupy more space, and have a significant history of violence. According to the United States’ State Department, the DRC shares 6,835 miles of land lake, and river borders with nine countries but lacks the capacity to effectively patrol them (United States Department of State, 2022) – though the territory of North and South Kivu, as well as Ituri, encompasses over 190,000 kilometers and a population of roughly 19.5 million people. In its 25-year history, MONUSCO would never receive the resources it needed to stabilize and sustain a war-torn region.

6The eastern DRC has been characterized by instability and violence where the ADF and M23 are present. Transportation is unsure, and civilians know that the area is troubled by the potential threat. Where states fail to create stability, multilateral organizations have stepped in. Because the issue transcends borders, this analysis considers international cooperation between local states, international organizations, and other stakeholders.

7Though there are over one hundred rebel groups in the DRC vying for control of its resources, challenging the government and each other, two principal groups have posed a lasting and existential threat to both the government and multilateral efforts to maintain peace. The ADF and the M23 have challenged MONUSCO and will continue to harass the DRC government after MONUSCO departs. To best understand the challenges that MONUSCO faced in the DRC, it is necessary to explore the composition and interests of those two rebel groups. According to many sources, to keep its strength, Tshisekedi’s government will compromise with M23 and Rwanda’s government (Shepherd, 2025; McMakin & Mwanamilongo, 2025).

Continued Threats to Regional Security

8The ADF and M23 remain a threat in the eastern DRC. The violent history of the ADF and M23 indicate that these groups are generally unpopular, but that they also enjoy a lasting foothold in the region. Indeed, the history of these two organizations illustrates that they existed prior to the MONUSCO arrival, have persisted through DRC government turnovers, and have local support which is often untrue of both UN peacekeepers and the government in Kinshasa.

A. The ADF

9 The ADF came together in the mid-1990s under the leadership of three different militia: the Allied Democratic Movement, the National Army for the Liberation of Uganda, and the Tablighi Jamaat movement. While the Allied Democratic Movement was primarily composed of rebels who did not join Ugandan President Museveni’s National Resistance Movement in the 1990s, the National Army for the Liberation of Uganda and the Tablighi Jamaat movement are predominately Congolese Muslim organizations (Nantulya, 2019). According to Ugandan news outlets, it was under the leadership of Jamil Mukulu that disparate rebel groups came together in Uganda under the title of ADF and established itself in North Kivu in the late 1990s (Kasasira 2015). Amid the chaos of the Rwandan genocide and the Second Congo War, the ADF secured an international region of control on both sides of the Uganda/DRC border.

10 In 2014, the DRC and UN targeted and splintered the ADF with joint arrests and military action. Leaders of the ADF, including Mukulu was arrested in 2015 (Kasasira, 2015). New leadership took over, and Musa Baluku now heads the ADF. With new leadership and organization, the ADF rebounded in 2017 and began one of the deadliest assaults on a UN peacekeeping force operating a base in the Beni Territory near the banks of the Semliki River (Congressional Research Service, 2022). The ADF established ties with the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) in 2017, and ISIS recognized ADF as an affiliate in 2019. Because the ADF created formal ties with ISIS in 2019, the US State Department also formally recognized it as an international terrorist organization and began referring to the ADF as the ISIS-DRC. Since 2019, the ADF has gained territory in the DRC, and it has projected force into neighboring Uganda and Rwanda. According to the US State Department, roughly a third of the ADF is of Ugandan origin (2022), and as such it may be able to traverse the border and access resources in Uganda. The ADF continues to threaten peace in the region. In 2021, the ADF took credit for suicide bombings in Kampala that killed 3 people and wounded dozens more (Biryabarema, 2021). Also in 2021, the Rwandan government disrupted an attempt by the ADF to carryout IED attacks in urban spaces (Congressional Research Service, 2022). The ADF poses a logistical and existential threat to both the DRC government and UN efforts in the region because it controls pockets of territory, using violence against governments and multilateral organizations in the region.

B. The M23

11 M23 came together in the Eastern Congo between 2012 and 2013 and is composed mostly of ethnic Tutsi soldiers. The group is named after the date – 23 March 2009 – when the DRC government signed a peace treaty to end a predominately Tutsi rebellion in the eastern part of the country. Like the ADF, M23 also emerged from the chaos of the Second Congo war, though made up primarily of ethnic Tutsi forces. Established in the Eastern DRC following the 1994 Rwandan genocide, generations of ethnic Tutsi soldiers competed with government forces until the M23 coalesced around CNDP (National Council for the Defense of the People) soldiers who rebelled about the DNC government. Many former CNDP soldiers took control of Goma, the capital and largest city in the North Kivu province, on 20 November 2012. Already in control of other regional towns, M23’s success here presented a genuine threat to the Kinshasa government. However, under pressure, these soldiers negotiated with the DRC government and withdrew in December 2012. According to Reuters, the agreement “concludes the most serious rebellion in Congo in a decade but the region remains fragile, not least because the agreement does not address the status of other armed groups” (Lough, 2013). M23’s control of the provincial capital illustrated not only its logistical sophistication, but it also signaled to civilians that the central government was unable to protect them.

12In 2012, M23 was likely receiving support from Rwanda, according to the UN. Among other things, M 23 soldiers reported that they were trained by the Rwandan government before being sent to fight for M 23 in the DRC (BBC, 2012). Since then, M23 has reportedly routinely received support from the Rwandan and the Ugandan government, according to a UN Security Council report (Wood, 2024). Though both the Rwandan and Ugandan governments deny this claim, it is generally accepted by international observers (Al Jazeera, 2024). Unlike ADF, M23 represents a local threat to the Congolese government that enjoys support from regional governments.

13 Though there is fierce competition between groups to control mines and other forms of illicit revenue, it is clear that M23 has other advantages relative to other local rebel groups. M23 controls two of the five regions in North Kivu and has established its own administrative governments there (Nantulya, 2024). According to a MONUSCO report in 2022, M23 has “conducted itself increasingly as a conventional army rather than an armed group” (UN Briefing, 2022). In terms of funding and sophistication, M23 rivals the Congolese government’s commitment to the region of North Kivu.

14 These groups - the ADF and M23 - remain the most prominent threats to the DRC government and people in the region, though there are reportedly over one hundred nonstate armed groups (Center for Preventative Action, 2024). Since the First Congo War (1996-1997), an estimated 6 million people have died as a result of the conflict (Center for Preventative Action, 2024), and currently there are about 7.2 million internally displaced people, while 23.4 million suffer from food insecurity (UN World Food Programme, 2024). The principal locations of these state failures are in the provinces of North Kivu, South Kivu, and Ituri. From here, the Wazalendo (a force taking its name for local patriot) at times sides with the FARDC (the Armed Forces of the Democratic Republic of the Congo) and at times fights with M23 without support. However, relying on local militia, while cost effective and local, can also result in human rights abuses and instability. The success of the ADF and M23, and the ubiquity of rebel groups, pose security threats to Congolese civilians as well as an existential threat to the Congolese government.

15 The region remains insecure and anarchic following the Congo wars as part of the failure of the Congo state. The Lusaka Ceasefire Agreement, brokered by the United Nations and signed by five regional states, promised to improve the security sector. The UN would act as a peacekeeping body and participate in capacity building with local leaders, according to UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon (Voice of America, 2013). According to the agreement, the UN pledged a peace-keeping mission of around 17,000 soldiers to support its mission there. However, the UN found problems executing and upholding this initial mandate. These problems are understood using Barnett and Finnemore’s (1999) bureaucratic pathologies conceptual framework.

Bureaucratic Pathologies and the UN

16 The UN’s mission in the DRC has included both peacekeeping and peacemaking forces. However, the example of the DRC illustrates a first experience of the UN creating peace, not just keeping it. Along with this new behavior, the UN faced a variety of pathologies common in international organizations. Multilateral peacekeeping operations, especially those executed by the United Nations, are often blamed for 1) inaction, 2) a changing or unclear mandate, 3) peacekeeper misconduct, and 4) mismanagement and insufficiently funded programs.

17 Multilateral organizations can be slow to act due to their structure. According to Schöndorf (2011, p. 32), these organizations are subject to opposing pressures to respond quickly to complex situations with diverse stakeholders and concerns. As such, these organizations are relatively slow acting, compared to rebel groups or individual governments (Lounsbery, Pearson, & Talentino, 2011). Likewise, international organization’s missions can change through time, whether as a result of responding to challenges from their execution and/or as a result of interests of competing contributing stakeholders (Morse & Keohane, 2014). To many international and domestic actors, the multilateral organization’s changing mandate represents a failure of its mission (Rich & Newmann, 2004). Domestic and international agents tug for their interests, and the environment conditions the pull both agents have. Their respective internal structures influence their ability to act.

18To explore these pathologies, it is necessary to understand problems inherent in ‘group projects’ and multilateral efforts by governments with shifting leadership coalitions. The first hypothesis that this article addresses is that each of these problems generally attributed to multilateral peacekeeping operations apply to MONSUCO. International organizations often are 1) slow to execute their initiatives, b) dither and oscillate in their commitment because they rely diverse coalitions and alienate local governments. These criticisms against MONUSCO are generally applicable, and they apply here as discussed below.

19 Importantly, though, the shortcomings of international actors may not be as damning as the absence of those international actors. Despite their problems, the circumstances in the DRC especially may necessitate failure-prone-but-essential multilateral forces like MONUSCO. The organizational strength of this mission remains relatively transparent, responsive to failure, and committed to genuinely improving the people’s lives which it intends to serve. MONUSCO may execute its mission with failings, but it has provided services to people in eastern Congo provinces that the government has and will continue to fail in terms of safety and service provision given the history of all of the involved parties.

A. Bureaucratic pathology of multi-lateral responses- Barriers between People and Their Governments.

20 Though the DRC government has neglected the western part of the country, MONUSCO also has become unpopular and seen as ineffective. According to Duursma et al, non-state armed groups may not necessarily see the UN as an honest broker if it has engaged in stabilization actions against them (Duursma et al., 2023). As part of MONUSCO’s mandate has been to help rebels transition to civilian life, recidivism has caused the UN to eye this population with skepticism. MONUSCO has also sacrificed its relationship with locals at the expense of the central government (Spijkers, 2015). Bureaucratic characteristics such as being unresponsive to their environments and prioritizing their own objectives rather than fulfilling the needs of local stakeholders. For this reason, along with complications in the UN’s execution of the mission in the DRC, MONUSCO has lost credibility with local stakeholders and then found itself out of favor with the new Tshisekedi government. The mistrust then applies to both the UN and to the local population. Likewise, MONUSCO has met with allegations of corruption and nepotism. According to Beigbeder (2021), fraud and corruption are embedded within the culture of the UN. Corruption charges plagued MONUSCO, against efforts for internal monitoring and discipline.

B. MONUSCO and Continued Violence in the DRC

21MONUSCO has failed to bring or sustain peace to the DRC since it began its the late 1990s. Popular sentiment and political will against the UN continues to gain ground, and President Tshisekedi has pledged to remove UN forces at the end of 2024 because of this failure. However, early on the organization devoted unprecedented resources to not only keep peace, but in an unprecedented move, work to create peace.

22To address the challenges of overseeing the disarmament of rebel groups and protection of civilians, the UN devoted a record number of soldiers and peacekeepers. Beginning with the moniker MONUC, the UN authorized a force of 5,537 military personnel including 500 observers, according to the United Nations Security Council Resolution 1291 (2000). Among its objectives was to “supervise and verify the disengagement and redeployment of parties’ forces’ and monitor compliance with the provision of the Ceasefire Agreement on the supply of ammunition, weaponry, and other war-related material to the field” (UN, 2000). The Community Disarmament and Resettlement program (CDR) section of the MONUC began in the Ituri region of the DRC and focused on disarming militias and offering aid to resettle belligerents (MONUSCO.org, 2024). MONUC and partner organizations, including UNICEF and the FARDC helped to transition rebels into civilian life or enlist in the FARDC. Designed to disarm belligerents and deliver aid to an at-risk population, MONUC struggled to achieve both objectives.

23Noting the dire need and overwhelming obstacles, in 2003 the United Nations Security Council Resolution 1493 provided MONUSCO personnel the authority to use all necessary means to fulfill its mandate in the Ituri region of the DRC. This resolution broadened the rules of soldiers’ rules of engagement. The number of personnel also increased to 10,800, significantly amplifying the UN presence though still a small number, given the enormous population and physical geography in its jurisdiction. MONUC forces were clustered in the districts of Ituri, North, and South Kivu. Among other things, the UN Peacekeepers were authorized to cordon and search domiciles and businesses suspected of operating as logistical hubs for the militias. Predictably, the UN became the target of militia attacks, and UN collaborators met with militia reprisals.

24By 2004, the fragile stabilizing efforts had seriously eroded. The governance vacuum provided space for a militia under command of Laurent Nkunda of the Rally for Congolese Democracy (RCD-Goma) to retreat to North Kivu (Masisi and Rutshuru territories) and start a government. Nkunda named this government the National Congress for the Defense of the People (CNDP), and he challenged other militia, the MONUC, and the DRC government for control. Concurrently, MONUC gained the ability to “seize or collect arms and any related material whose prese in the territory of the DRC violates the measures imposed in Resolution 1493” – largely weapons of war. In both 2000 and 2004, the UN authorized “all necessary means within its capacity” to carry out its tasks. Seldom before had so many UN peacekeepers been asked to fulfill a mandate which was essentially peace-making.

25Nkunda’s forces opposed all pretenders, including the UN, the DRC government, and other militias, but his leadership was short lived. In 2009, Nkunda traveled to Rwanda and was arrested by the Rwandan military. While many of his soldiers dispersed, others continued under new leadership (Gettleman, 2009). His chief of staff, Bosco Ntaganda, became representative of the CNDP in the DRC. Ntaganda deepened his control in the Eastern DRC. The CNDP ruled over several lucrative mines in the region and continued to threaten the UN and the DRC government. In 2013, Ntaganda handed himself over to the U.S. embassy in Kigali. It is speculated that he did so to avoid conflict with M23 which was also gaining strength. Also in 2013, the UN adopted Resolution 2098, creating a specialized ‘intervention brigade’ with a troop ceiling of 19,815: it would consist of three infantry battalions, one artillery and one special force and reconnaissance company with headquarters in Goma and operate under direct command of the MONUSCO Force Commander, with the responsibility of neutralizing armed groups and the objective of contributing to reducing the threat posed by armed groups to state authority and civilian security in eastern DRC and to make space for stabilization activities. MONUSCO would reach the zenith of the size of its multilateral fighting force but would be unable to dislodge the militias.

26Protests to remove MONUSCO began to influence politics in 2022. In July 2022, Senator Bahati Lukwebo visited Goma and called for MONUSCO to withdraw from the DRC. In the ensuing days, crowds protested the UN base. Rioters attacked the base and the homes of UN personnel. The violence spread from Goma to Butembo and Uvira, with 19 killed (including three UN peacekeepers) and 86 Congolese injured (Wembi & Dahir, 2022).

27Following the protests, presidential candidate Felix Tshisekedi campaigned on removing the UN from the Congo upon election. With a large majority, Tshisekedi won election, and began the process of removing UN forces from eastern Congo. On 21 November, 2023, Congo’s Foreign Minister and the head of the United Nations stabilization mission in the Congo signed an agreement setting an end to the UN’s stabilization. In 2024, MONUSCO began drawing back its forces. On 19 April, MONUSCO transferred the Bunyakiri base in South Kivu to the Armed Forces of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUSCO, 2024). On 30 April, MONUSCO formally ceased operations in South Kivu.

28While MONUSCO is leaving the DRC, there is no clarity that violence will end. According to MONUSCO press releases, M23 continues to harass eastern Congolese populations. The Congolese government understands this challenge. The Deputy Prime Minister stated that “the withdrawal of MONUSCO does not mean the end of the war or the end of the security crisis…To all Congolese, we must continue to fight” (Radio Okapi, 2024). Though MONUSCO has struggled to achieve peace, its absence is almost certain to destabilize the region. Congolese President Felix Tshisekedi asked MONUSCO’s forces to leave by the end of 2024, and the UN peacekeeping organization phased out its soldiers. Likewise, the Congolese government has asked Uganda to remove its soldiers from the east, a force which has been patrolling since 2021. According to local human rights activists, though, there is little guarantee of peace when international forces leave. In an anonymous interview, an activist reports, “in the absence of a robust international presence, there is a growing risk that groups will engage in violent clashes for control of natural resources and territory, endangering the lives of civilians and the fragile peace that currently prevails in some areas. Accusations of war crimes and human rights violations by certain elements resistant to peace are fueling fears of an escalation of violence and instability if UN soldiers were to withdraw completely from the region” (cited in Kahombo, Hengelela, & Mabwilo, 2024, p. 39). Indeed, within the first few months of 2025, 700,000 people have been displaced by increased violence (UN, 2025). More police, not less, are asked for by locals in this violence-prone region.

29In general, international organizations can separate people from a responsive government. The DRC enjoyed its first peaceful transfer of power in Tshisekedi’s election, bringing some hope that the democratically elected president will be responsible to its citizens. The Tshisekedi administration has rotated partners in the east, bringing some hope for change in the troubled region (McMakin & Mwanamilongo, 2025). This conjecture though, that international organizations separate people from their governments, true of UN in general and MONUSCO in particular. According to Nantulya the idea of MONUSCO is fundamentally problematic. According to Nantulya (2024), “it distracts from and attempts to absolve the government of its cardinal responsibility to protect its own citizens”. According to a variety of sources, the UN has never provided an immediate or sufficient response to violence and crime. Even in the areas of the DRC where the organization has the most services and soldiers deployed, critics argue that MONUSCO has not prevented violence and cannot even protect itself.

30Whoever is to blame, it is clear that the Congolese government is seeking to change strategies. In December of 2023, the East African Community Regional Force (EACRF) was also asked to leave Congo. According to the government, the regional force did not complete its mandate. Among other things, the regional force was to enforce resolutions that rebel groups made with the DRC government to end the fighting. The Nairobi accords traded peace for prisoners, and it attempted to end the practice of child soldiers (Wambui, 2022).

31Though without multilateral support, it is not clear that the DRC government will secure the region (Golooba-Mutebi, 2023). For instance, South Kivu Province bases have fallen into disrepair since the UN withdrawal in April (Le Monde Afrique, 2024). According to the Agence France-Presse, the MONUSCO bases in South Kivu had been vandalized and looted immediately following the withdrawal, and roughly half of the 115 police officers assigned to the base had deserted (2024). There are other examples from both international and local sources reporting in the first few months of 2025. Newspaper reports and residents’ testimonies in February and March suggest a climate of fear and uncertainty in the DRC’s Kivu provinces (Kahombo, Hengelea, & Mabwilo, 2024). On 22 February, 12 young men were shot dead in Goma by M23 because they refused to join the group (Maludi, 2025). In South Kivu’s capital, Bukavu, on 27 February an explosion occurred killing 11 people and injuring dozens more (Barhahiga & Pronczuk 2025). In addition to individual incidents, more than 700,000 people have been displaced by the conflict since January 2025 (UN, 2025) and several thousand people have been killed (Livingstone, 2025). The governance vacuum is evident in logistical failures in the police force (Le Monde Afrique, 2024), mounting unemployment (Radio Okapi, 2024), and the increasing legitimacy of the rebel groups (Kahombo, Hengelea, & Mabwilo, 2024). Whether because of MONUSCO’s withdrawal or because of an emboldened M23, instability is increasing in the region.

C. Mandate Drift in the DRC

32Another bureaucratic pathology inherent in MONUSCO’s mission in the DRC has been the expansion of its mission, otherwise known in the literature as a mandate drift. Whereas in its first years, MONUC was firmly committed to cordon-and-search operations. These coercive operations, “fall in a gray area between traditional peacekeeping and ’peacemaking’, which is more closely related to warfighting” (Berkman & Holt, 2006, p. 157). Indeed, what this meant in practice was that the United Nations took the rare step of not only peacekeeping, but peacemaking in the DRC. Following the Lusaka Ceasefire Agreement in July 1999, the Security Council established the MONUC in Resolution 1279 on 29 November, 1999. The second Congo war ended in 2002, though the eastern most provinces continued to be violent. Rwanda and Uganda infrequently directly intervened, but the DRC government under Joseph Kabila found evidence that Rwanda was supporting rebel groups.

33On 1 July, 2010, the Security Council replaced MONUC with the MONUSCO which was authorized to protect civilians, humanitarian personnel and human rights groups in the DRC. Resolution 1925 established a maximum of 19,815 military personnel, and over two thousand other military observers, police, and support workers. The most significant difference between Resolution 1925 and Resolution 1279 was the new mission to defend international personnel providing aid and personnel responsible for delivering that aid. In its later years, the revised MONUSCO did everything from retraining rebels to providing humanitarian aid and creating safe zones. MONUSCO became a central administrative body to coordinate NGO aid, but it was also held in skepticism by NGOs due to its human rights record and its relationship with the DRC government.

34The mandate drift necessarily included stabilization and protection efforts in recognition of the continued violence. As discussed above, M23, the ADF, and up to a hundred other rebel groups continued to wreak violence in the eastern DRC. Reports suggested that this violence was supported by regional powers, including Uganda and Rwanda for different rebel groups. These rebel groups also sought control over the most important resources in the area, namely trade and the mines responsible for exporting rare metals (Rupert, 2024). These mines are a flashpoint of conflict. Chinese firms own the majority foreign-owned mines, and the Chinese government has asked the DRC government to deploy soldiers to protect these assets (Center for Preventive Action, 2024).

35In response to this concern of mandate drift, UN supporters advocate ‘complexity theory’ – the concept that uncertainty and unpredictability characterize complex systems (Cilliers, 1998), and that adapting to a dynamic environment is necessary so long as the organization abides by principled adaptation (Folke, 2006). While true, applying this theory to MONUSCO’s specific, DRC mission has attracted few supporters locally. Instead, critics argue that MONUSCO has insufficiently executed a mandate ignorantly devised.

D. Creates Own Problems in Executing Its Mission

36Perhaps the most damning fault of MONUSCO was its failure to control its own soldiers during its mission. MONUSCO soldiers faced allegations of sexual exploitation and attacks in its 25-year history in the DRC. According to Kovatch, MONUC and MONUSCO peacekeepers in the DRC were both protectors and perpetrators of violence (2016). From early on in its mission, the MONUSCO and MONUC peacekeepers were accused of sexual violence in the eastern DRC. Human Rights Watch reported on this crime in 2004, warning that women and children were being exploited and trafficked. In April 2008, the UN appointed a Senior Adviser and Coordinator on Sexual Violence in the DRC who helped to develop a Comprehensive Strategy on Combating Sexual Violence in the DRC.

37Again in 2016, UN Peacekeepers made headlines as critics elevated allegations against them for sexual abuse (Sengupta, 2016). Then Secretary Ban Ki-Moon, created a new precedent in response to the abuse by UN Peacekeepers, and removed an entire battalion of DRC soldiers (Sengupta, 2016; United Nations, 2016). United States Ambassador to the UN, Samantha Power, recognized the systemic gaps in reporting in the DRC and reasoned that the number of actual allegations against the peacekeepers ‘could be far worse’, indicating that the reported numbers likely represent a fraction of actual cases (Associated Press, 2015). In these regions, not only were rebel groups, the FARDC, and regional peacekeepers accused of human rights abuses, but also peacekeepers from the UN’s MONUSCO mission.

38The UN responded to sexual exploitation and abuse by mission personnel in a variety of ways. For example, in 2023 troops in the Malawi and South African contingents underwent training in women’s rights and the promotion of human rights. Alleged perpetrators from these same countries were recalled back to their respective countries (Rolley & Mahamba, 2023). And finally, MONUSCO’s website includes information for women who gave birth to children whose fathers are MONUSCO soldiers.

39Like other responses, the UN response to sexual abuse was characterized as slow (United States House Committee, 2004). Despite outrage at its highest level, the inability for UN forces to self-police against sexual violence has meant continued violence against women. With reference to sexual attacks in the DRC, Sec. Annan voiced his outrage in 2004 (UN Press Release, 2004) and Ban Ki-Moon called it a cancer in the system in 2015 (Associated Press, 2015). Secretary-General Antonio Guterres devoted new efforts in 2017 to combat the continued violence, implementing reporting measures, victim outreach, increased training for personnel and staff, and means by which victims could seek support for children who resulted from rape. Reports have been tracking upward though, with 758 allegations in 2023, 534 in 2022, and 265 in 2018 (United Nations News, 2024). As Powers noted earlier, and as the UN General Assembly report indicates, a significant number of victims fear retaliation for reporting their abuse (General Assembly, 2024). Roughly 90% of the cases reported to the UN in 2023 were in either the DRC or the UN mission in the CAR, illustrating that problem of sexual violence continues within UN operations.

40Women now hold the top positions at MONUSCO, though field operations are still governed by male military staff. Since 2021, MONUSCO has been led by Special Representative Bintou Keita, a woman from Guinea, with Deputy Special Representative for Protection and Operations Vivian van de Perre of the Netherlands replacing Mr. Khassim Diagne (Senegal) who held the position from 2021-2024. With women in leadership positions in the DRC, effort to curtain sexual violence is likely to remain steady (Stiehm, 2001), though misconduct in operations may require more women accompanying men in the field (Heinecken, 2015). Indeed, where the FARDC are known to prey on civilians, blending former rebels with regular army, MONUSCO has proved to be relatively more disciplined (Berkman & Holt, 2006). In both sexual assaults and soldier misconduct, MONUSCO has a track record of disciplining parties responsible. The FARDC has been relatively less transparent, and its unwillingness to self-discipline has engendered mistrust.

Conclusion

41 Multilateral security efforts are often fraught with logistical and strategic missteps given the complexity of the threats that they address, and the challenges involved in coordinating many diverse actors. International security threats in the DRC represent a recent example of a dire humanitarian crisis for which the multilateral strength of the UN is uniquely able to address. State failure in the DRC, Uganda, and Rwanda in the 1990s required international intervention to keep and – in some cases – establish peace where states’ legitimate use of force was insufficient. The transnational characteristics of the ADF, M23, and others invite a coordinate response by neighboring states, but given those states’ domestic instability and adversarial relationships with each other, intervention by a third party made sense logistically and politically.

42 MONUSCO has failed in many respects in the DRC. Multilateral intervention forces fundamentally stand between a people and their government, though advocates for such intervention argue that at least initially, this is necessary. According to this analysis, it is clear the MONUSCO suffered from the bureaucratic pathologies that Barnett and Finnemore (1999) identified, and that these pathologies contributed to the suffering of the Congolese people. MONUSCO has itself been responsible for attacking civilians, especially attacking women. It has expanded its initial mandate to include not only peacekeeping, but also humanitarian outreach. It is also true that MONUSCO’s withdrawal has contributed to the reconfiguration of local power dynamics. When Tshisekedi’s government is achieving peace, as seen through negotiations with M23, observers can intuit a position of strength where a government is delivering on its promises to resolve the conflict in the east. However, critiques can equally scorn Tshisekedi for compromising with rebels and inviting another Scramble for Africa.

43Despite these problems, MONUSCO has provided a stabilizing force in the Eastern DRC. Outmatched against rebels and the conflicting interests of the Ugandan and Rwandan governments, MONUSCO has delivered essential services to millions of people through the decades. It has partially demilitarized a region where formal state governments (the DRC, Uganda, and Rwanda) are unable to create security or provide public health resources. Where the FARDC blends former rebels with regular the army, MONUSCO has proved to be relatively more disciplined. Because MONUSCO has also lost trust of the Congolese, as is evident in the 2024 protests, it will be imperative that the FARDC disciplines its soldiers as it seeks to bring peace to eastern Congo.

44There are also broader lessons about multilateralism given MONUSCO’s history in the DRC. First, from this analysis of bureaucratic pathologies, we can see that multilateral efforts at peacekeeping continue to be fraught with problems entirely inherent in the organization intervening. MONUSCO, in the execution of its mission, committed human rights abuse and failed to deliver the security that the UN promised. The analysis above illustrates that multilateral organizations continue to exhibit the pathologies that Barnett and Finnemore (1999) theorized. Secondly, though multilateralism through the UN brought its own problems, MONUSCO has been a stabilizing force. Though it is impossible to compare MONUSCO’s decades of intervention against its non-intervention, the chaos in eastern Congo following MONUSCO’s departure provides at least some corollary logic to reason that it kept peace and provided resources – that without MONUSCO, there are problems. Finally, this analysis shows that multilateralism remains a complex option, especially in the case where international organizations are involved. In the DRC, MONUSCO’s mission was to stabilize a region when the international organization (the UN) conditioned its resources, the host government (the DRC) failed to reinforce its work, and regional states (Uganda and Rwanda) actively worked against it. In this instance, multilateralism provided another dimension for the domestic politics of the states involved while millions of people suffered at the hands of violent rebels.

45The DRC government under Tshisekedi’s government has asked the UN’s mission to leave the Congo in 2025, and forces are drawing down. MONUSCO’s problematic history and inability to deliver lasting peace to the people in eastern Congo led the Congolese to demand its removal. The departure of this long-time peacekeeping force promises to bring change to the war-torn region, but it is unclear that the change will bring more stability.

Bibliographie

Agence France-Presse, ‘DR Congo Police Fend For Themselves After Peacekeepers Quit UN Base’, 2024, https://www.thecitizen.co.tz/tanzania/news/africa/dr-congo-police-fend-for-themselves-after-peacekeepers-quit-un-base-4608554.

Al Jazeera, ‘Uganda Backed M23 in DRC, Rwanda’s ‘de facto control’ on group: UN Experts’, 2024, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/7/9/uganda-backed-m23-in-drc-rwandas-de-facto-control-on-group-un-experts.

Associated Press, ‘Ban Ki-moon says sexual abuse in UN peacekeeping is 'a cancer in our system'’, 2015, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/aug/14/ban-ki-moon-says-sexual-abuse-in-un-peacekeeping-is-a-cancer-in-our-system.

Balingene Kahombo B., ‘Corruption and its Impact on Constitutionalism and Respect for the Rule of Law in the Democratic Republic of the Congo’, in Fombad C. M. and Steytler N. (ed.), Corruption and Constitutionalism in Africa: Revisiting Control Measures and Strategies, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2020.

Barhahiga J. and Pronczuk M., ‘At Least 11 Dead and Scores Injured in Congo After Blasts at M23 Rebel Leaders’ Rally, Rebels Say’, Associated Press, 2025, https://apnews.com/article/congo-m23-rebels-explosion-meeting-40328c06af96d0a2728d9d5c20305595.

Barnett M. and Finnemore M., ‘The Politics, Power, and Pathologies of International Organizations’, International Organization, vol. 53, n° 4, 1999, pp. 699-732.

Bbc, ‘Rwanda ‘supporting the DR Congo mutineers’’, 2012, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-18231128.

Beigbeder Y., ‘Fraud, Corruption, and the United Nations’ Culture’, in Dijkzeul D. and Salmons D. (ed.), Rethinking International Organizations Revisited: Agency and Pathology in a Multipolar World, Berghahn Books, New York, 2021.

Berkman T. and HOLT V., The Impossible Mandate? Military Preparedness, The Responsibility to Protect, and Modern Peace Operations, The Henry L. Stimson Center, Washington DC, 2006.

Center For Preventative Action, Conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Global Conflict Tracker, 2024.

Cilliers P., Complexity and Post-modernism. Understanding complex systems, Routledge, 1998.

Congressional Research Service, The Allied Democratic Forces, an Islamic State Affiliate in the Democratic Republic of Congo, 2022.

Diel P. and Druckman D., Evaluating Peace Operations, Lynne Reiner, Boulder, Co, 2010.

Dijkzeul D. and Beigbeder Y., Rethinking International Organizations: Pathology and Promise, Berghahn Books, New York, 2004.

Dijkzeul D. and Salmons D., Rethinking International Organizations Revisited: Agency and Pathology in a Multipolar World, Berghahn Books, New York, 2021.

Duursma A., Bara C., Wilén N., Hellmüller S., Karlsrud J., Oksamytna K., Wenger A. et al., ‘UN Peacekeeping at 75: Achievements, Challenges, and Prospects’, International Peacekeeping, vol. 30, n° 4, 2023, pp. 415–476, https://doi.org/10.1080/13533312.2023.2263178.

Folke C., ‘Resilience: The emergence of a perspective for social-ecological systems analyses’, Global Environmental Change, vol. 16, n° 3, 2006, pp. 253-267.

George A. L. and Bennet G., Case Studies and Theory Development in the Social Sciences, MIT Press, Cambridge, 2005.

Gettleman J., ‘With Leader Captured, Congo Rebel Force is Dissolving’, New York Times, 2009, https://www.nytimes.com/2009/01/25/world/africa/25congo.html.

Golooba-Mutebi F., ‘Congo Crisis: The Responsibility of the DRC Government’, The Pan African Review, 2023, https://panafricanreview.com/congo-crisis-the-responsibility-of-the-drc-government.

Heinecken L., ‘Are Women ‘Really’ Making a Unique Contribution to Peacekeeping? The Rhetoric and the Reality’, Journal of International Peacekeeping, vol. 19, 2015, pp. 227-248.

Kahombo B., Hengelela J., and Mabwilo J. R., Planned withdrawal of MONUSCO from the Democratic Republic of Congo: Challenges and Prospects, Africa Security Sector Network, 2024.

Kasasira R., ‘Who is ADF’s Jamil Mukulu?’, The Daily Monitor, 2015, https://www.monitor.co.ug/uganda/lifestyle/reviews-profiles/who-is-adf-s-jamil-mukulu--1620396.

Keohane R. O., ‘Multilateralism: an agenda for research’, International Journal, vol. XLV, n° 4, 1990, pp. 731–764.

Kovatch B., ‘Sexual Exploitation and abuse in UN peacekeeping missions: A Case study of MONUC and MONUSCO’, Journal of Middle East and Africa, vol. 7, n° 2, 2016, pp. 157-174.

Le Monde Afrique, ‘RDC : après le départ des casques bleus du Sud-Kivu, des policiers congolais livrés à eux-mêmes’, 2024, https://www.lemonde.fr/afrique/article/2024/04/30/rdc-apres-le-depart-des-casques-bleus-du-sud-kivu-des-policiers-congolais-livres-a-eux-memes_6230745_3212.html.

Livingstone E., ‘Eastern DRC: The Impossible Death Toll of the Battle for Goma’, 2025, https://www.theafricareport.com/378768/eastern-drc-the-impossible-death-toll-of-the-battle-for-goma.

Lough R., ‘Congo Signs Peace Deal with M23 Rebels’, Reuters, 2013, https://www.reuters.com/article/world/congo-signs-peace-deal-with-m23-rebels-idUSBRE9BB0X0/.

Lounsberry M. O., Pearson F., and Talentino A. K., ‘Unilateral and Multilateral Military Intervention: Effects on Stability and Security’, vol. 7, n° 3, 2011, pp. 2270257, DOI: 10.1080/17419166.2011.600585.

Maludi H., ‘A Goma, un mois sous le joug de M23’, Afrique XXI, 2025, https://afriquexxi.info/A-Goma-un-mois-sous-le-joug-du-M23.

Mcmakin W. and Mwanamilongo S., ‘Congo’s Government and Rebels Say they Are Working Toward a Truce in the East’, Associated Press, 2025, https://apnews.com/article/congo-m23-ceasefire-7b50a019e45e08798c40e8192abbcfda.

Monusco.Org, Press Releases, 2024, https://monusco.unmissions.org/en/press-releases (accessed 17 October 2024).

Morse J. C. and Keohane R. O., ‘Contested Multilateralism’, Review of International Organizations, vol. 9, 2014, pp. 385-412.

Nantulya P., Escalating Tensions between Uganda and Rwanda Raise Fear of War, Spotlight, 2019, https://africacenter.org/spotlight/escalating-tensions-between-uganda-and-rwanda-raise-fear-of-war/(accessed 3 July 2019).

Nantulya P., Understanding the Democratic Republic of the Congo’s Push for MONUSCO’s Departure, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, 2024.

Radio Okapi, ‘Au moins 5000 personnes se retrouvent sans emploi après le départ de la MONUSCO du Sud-Kivu’, 2024, https://www.radiookapi.net/2024/06/01/actualite/societe/au-moins-5000-personnes-se-retrouvent-sans-emploi-apres-le-depart-de-la.

Rich R. and Newman E., ‘Introduction: Approaching Democratization Policy’, in Newman E. and Riche R. (ed.), The UN Role in Promoting Democracy. Between Ideals and Reality, United Nations University Press, New York, 2004.

Rolley S. and Mahamba F., ‘Eight UN Peacekeepers Detained in Congo over sexual abuse claims, sources say’, Reuters, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/un-suspends-some-peacekeepers-congo-denounces-sexual-abuse-2023-10-12/.

Rupert J., ‘In Congo, Peace Means a Halt to ‘Brutal, Illegal’ Mining’, United States Institute of Peace, 2024, https://www.usip.org/publications/2024/03/congo-peace-means-halt-brutal-illegal-mining.

Schöndorf E., Against the Odds: The Ill-Structured Conditions, Organizational Pathologies, and Coping Strategies of United Nations Transitional Administrations, University of Konstanz, 2009.

Sengupta S., ‘US Senators Threaten UN over Sex Abuse by Peacekeepers’, New York Times, 2016, http://www.nytimes.com/2016/04/14/world/africa/us-senators-threaten-un-over-sex-abuse-by-peacekeepers.html.

Shepherd B., ‘Events in the DRC Show a New Realpolitik is Emerging in Africa – One That is Fraught with Danger’, Chatham House, 2025, https://www.chathamhouse.org/2025/02/events-drc-show-new-realpolitik-emerging-africa-one-fraught-danger.

Spijkers O., ‘The evolution of United Nations peacekeeping in the Congo: from ONUC, to MONUC, to MONUSCO and its Force Intervention Brigade’, Journal of International Peacekeeping, vol. 19, n° 1-2, 2015.

Stiehm J. H., ‘Women, Peacekeeping and Peacemaking: Gender Balance and Mainstreaming’, International Peacekeeping, vol. 8, 2001, pp. 39-48.

Un Monuc, Mandate, 2025, https://peacekeeping.un.org/ru/mission/past/monuc/mandate.shtml.

Un Monusco, Background, 2025, https://monusco.unmissions.org/en/background.

Un News, ‘We’re afraid to return home’: Uprooted again, Congolese civilians face hunger and more insecurity, 2025, https://news.un.org/en/story/2025/02/1160486 (accessed 25 February 2025).

Un News, DR Congo: Ban condemns killing of UN peacekeeper, 2016, https://news.un.org/en/story/2016/12/548182 (accessed 19 December 2016).

Un Press Release, SG Kofi Annan, Secretary-General “Absolutely Outraged” by Gross Misconduct by Peacekeeping Personnel in Democratic Republic of Congo, UN Doc. SG/SM/9605, 2004, www.un.org/News/Press/docs/2004/sgsm9605.doc.htm.

Un Security Council, Res. 1279 (1999), S/RES/1279, 1999.

Un Security Council, Res. 1291 (2000), S/RES/1291, 2000.

Un Security Council, Res. 1493 (2003), S/RES/1493, 2003.

Un Security Council, Res. 1925 (2010), S/RES/1925, 2010.

Un Security Council, Res. 2098 (2013), S/RES/2098, 2013.

United Nations News, ‘Sexual Exploitation and Abuse: UN Intensifying Efforts to Uphold Victim’s Rights’, 2024, https://news.un.org/en/story/2024/03/1148016.

United Nations Surveys Of Crime Trends And Operations Of Criminal JUSTICE Systems Series (UN-CTS), 2018, https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/data-and-analysis/statistical-activities.html.

United Nations World Food Programme, Democratic Republic of the Congo, 2024, https://www.wfp.org/countries/democratic-republic-congo..

United States Department Of State, Country Reports on Terrorism 2022: Democratic Republic of Congo, 2022.

United States House Committee On International Relations, Testimony of Anneke Van Woudenberg, Human Rights Watch, 2004, https://www.hrw.org/news/2005/02/28/monuc-case-peacekeeping-reform.

Voice Of America, ‘African Leaders Sign DRC Peace Deal’, 2013, https://www.voanews.com/a/african-leaders-sign-deal-for-drc/1609673.html.

Wambui M., ‘53 Armed Groups in DR Congo Commit to end War’, The Daily Monitor, 2022, https://www.monitor.co.ug/uganda/news/53-armed-groups-in-dr-congo-commit-to-end-war-4046010.

Wembi S. and DAHIR A. L., ‘U.N. Peacekeepers Kill 2 and Would 15 in Congo’, New York Times, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/08/01/world/africa/congo-un-peacekeepers-kill-2.html.

Wood R., ‘Explanation of Vote Following the Adoption of a UN Security Council Resolution on the Democratic Republic of Congo’, 2024, https://usun.usmission.gov/explanation-of-vote-following-the-adoption-of-a-un-security-council-resolution-on-the-democratic-republic-of-the-congo/.

Para citar este artículo

Acerca de: Ryan Gibb

Ryan Gibb is an Associate Professor of International Studies at Baker University in Baldwin City, Kansas. Ryan conducted dissertation research in Uganda as Fulbright-Hays Doctoral Dissertation Research Abroad recipient and has published in Africa Spectrum, Electoral Studies, and Sage Research Methods along with contributing chapters to edited books including the recently published book, The Narrative of Africa Rising: Changing Perspectives. Along with these interests, Ryan researches pedagogy and citizen-scholar activism in modern America.