Analysis of rare and endemic flora in northeastern Algeria: the case of the wilaya of Souk Ahras

Abstract

Scarcity and endemism are considered the most important concepts of a region’s biodiversity and conservation. Nevertheless, our understanding of the models of scarcity and endemism is limited to high biodiversity regions as, for example, the wilaya of Souk Ahras, northeastern Algeria. In this study, we have compiled a list of all heritage species, their taxonomic composition, and geographic distribution. A total of 119 species was documented, and their distribution was as analyzed in the biological environments of two distinct phytogeographic sectors — C1 and H2. The rate of scarcity and endemism increased alongside the organic matter richness and, as a result, the forest and pre-forest area supported an over-representation of these species. The preservation of this biodiversity, exceptional and threatened, urgently requires appropriate scientific studies and environmental protection as short term measures.

1. Introduction

1The distribution and abundance of species are key in ecology and biogeography (Huang et al., 2016). The concept of endemism states that a taxon is limited in its distribution to a distinct area, which is the heart of biogeography (Anderson, 1994), and an important criterion for the conservation of biodiversity on a global, national, and local scales (Myers et al., 2000; Riemann & Ezcurra, 2005). Rare plants have great conservation value, either for their heritage or their risk of extinction (Gaston, 1991; Pimm et al., 1998).

2The identification of the vital areas for preserving biodiversity, with high concentration of closely related species (Myers et al., 2000; Médail and Diadema, 2006), becomes a fundamental task for the biogeography conservation (Cañadas et al., 2014; Morrone, 2018). With a richness of 25000 vascular plant species, half of which are endemic and are well adapted to dry periods (Quézel, 1995; Véla and Benhouhou, 2007), among the 34 hotspots in plant diversity on the planet (Myers, 2003), the Mediterranean basin is ranked as the third richest hotspot (Mittermeier et al., 2004), with additional complex geological, biological and cultural character (Blondel et al., 2010).

3Algeria, due to its geographical position, is part of this hotspot with 4449 taxa, 6.5 % of which are endemic (Dobignard and Chatelain, 2010-2013), with a high rarity index. More than three quarters (77.9 %) of the strict endemic taxa of Algeria are rare plants, representing less than a quarter of the total number of plants (Véla and Benhouhou, 2007). Despite being classified as a biodiversity hotspot, several regions of this country are yet to be explored (Benhouhou et al., 2018).

4In order to safeguard the plant biodiversity of these threatened regions, it is imperative to establish benchmarks that describes their biodiversity (Primack et al., 2012), by updating the taxonomic nomenclature of the Algerian flora (Amirouche and Misset, 2009). This can be carried out with collaboration between scientists and amateurs, active field work, and taxonomic problem solving (Domina et al., 2015).

5Work on rare and endemic flora in Algeria has been excessively confined to its geography (Hamel et al., 2013; Zedam, 2015; Miara et al., 2017, 2018; Mansouri et al., 2018; Djebbouri and Terras, 2019; Gordo and Hadjadj-Aoul, 2019). Furthermore, the touchstone study on endemic and/or rare plants in Algeria by Véla and Benhouhou (2007) was based on old data from the flora of Quézel and Santa (1962–1963).

It is in this context that the current work is rooted, proposing an inventory and an update on the rare and endemic flora present in the wilaya (or department) of Souk Ahras. Thereby, here we suggest a starting point for new conservation projects and research on local flora.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Study area

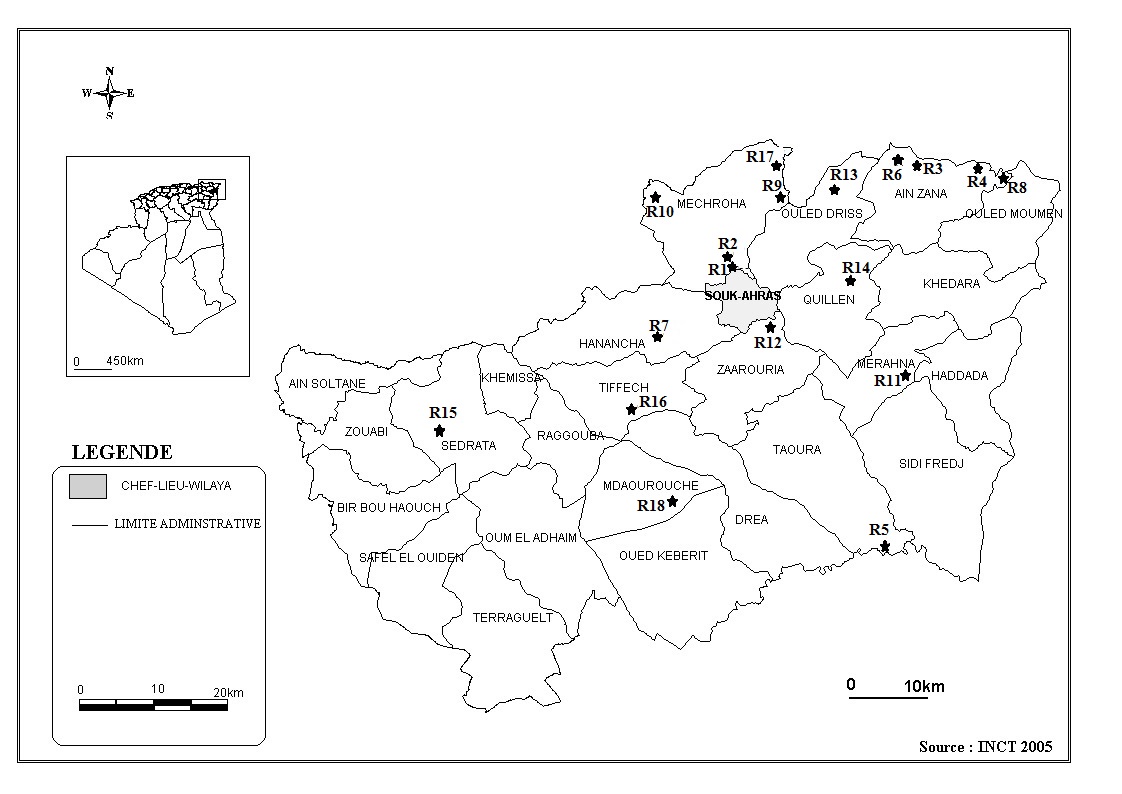

6The wilaya of Souk Ahras, located in the extreme northeast of Algeria, is limited in the north and west by the wilayas of El Tarf and Guelma, southwest by the wilaya of Oum el Bouaghi,

7southeast by the wilaya of Tebessa, and in the east by Tunisia (Figure. 1). This region is part of the 11th regional biodiversity hotspot in the Mediterranean, called “Kabylias–Numidia–Kroumiria” (Véla and Benhouhou, 2007), and covers the Important Plant Area (IPA) called “El Kala 2” (Yahi et al., 2012; Benhouhou et al., 2018).

Figure 1: Geographical location of the study sites

8Two heterogeneous sets determined the geomorphological configuration of this wilaya: the north (C1) was represented by mountains and forests and made up of 12 municipalities, with a total area of 1880 km2, characterized by a humid and subhumid bioclimates, with an average rainfall of 730 mm/year; the south (H2) made up of high plains and pastures encompassing 14 municipalities, covering an area of 2480 km2, and characterized by a semi-arid bioclimate, with an average rainfall of 350 mm/year (Hamaidia and Berchi, 2018).

9The average daily temperature varied according to the seasons (from 10 °C in January to

47 °C in August). Average monthly temperatures were 15 °C in January and 35 °C in July (CONM, 1990-2020). In this wilaya, the wooded area amounted to 82,375 ha. It comprised of two definite parts separated by the Medjerda wadi: to the north the cork oak (Quercus suber L.) and zeen oak (Quercus canariensis Willd.), and to the south the Pinus halepensis Mill. (Boudy, 1955). The ecosystems were similar as those of the rest of Numidia (forests, maquis, humid environments, and lawns), except for the coast and the dune compounds (see de Bélair et al., 2005).

2.2 Methodology

2.2.1 Floristic study

10The list of rare and endemic species was established according to a systematic sampling, from 2017 to 2020, from floristic surveys. This data collection was carried out at the level of forests of zeen oak (Quercus canariensis Willd.), cork oak (Quercus suber L.), matorrals of Pistacia lentiscus L., Olea europaea L., rocky areas, water bodies, neighboring lawns, and steppes (Macrochloa tenacissima (L.) Kunth and Artemisia herba-alba Asso), according to the phytosociological method of Braun-Blanquet et al. (1952).

11At the level of each site, ecological parameters were studied, namely the specific richness of rare and endemic species, altitude, and precipitation (see Table 1).

Table 1: The coordinates of the sampled stations

|

Code |

Sites |

GPS coordinates |

Biogeographic sector (Quézel and Santa) (1962-1963) |

Type of vegetation |

Precipitation (mm/year) (CONM, 1990-2020) |

Altitude (m) |

Bioclimate (CONM, 1990-2020) |

|

R1 |

Ain senour |

36°19'25"N ; 7°52'30"E |

C1 |

Lawn |

945 |

843 |

Humid |

|

R2 |

Ain Talhi |

36°20'22"N ; 7°51'40"E |

C1 |

Matorral |

945 |

853 |

Humid |

|

R3 |

Ain Trab |

36°21'53"N ; 8° 7'59"E |

C1 |

Humid environment |

884 |

902 |

Humid |

|

R4 |

Ain Zena |

36°24'02"N ; 8°11'28"E |

C1 |

Matorral |

842 |

1155 |

Humid |

|

R5 |

Ben Attia |

36°01’31"N ; 8°06’38"E |

H2 |

Steppe |

266 |

517 |

Semi-arid |

|

R6 |

Djebel Mcid |

36°23'56"N ; 8°3'28" E |

C1 |

Matorral |

972 |

1383 |

Humid |

|

R7 |

Hannecha |

36°13′1″N ; 7°49′60″ E |

C1 |

Matorral |

712 |

847 |

Sub-humid |

|

R8 |

Pool of Ain Zena |

36°24′2″N ; 8°11′28″E |

C1 |

Humid environment |

837 |

839 |

Humid |

|

R9 |

Mazeraa |

36°23'7"N ; 7°53'13"E |

C1 |

Zeen oak forest |

1124 |

925 |

Humid |

|

R10 |

Machroha |

36°21′26″N ; 7°50′8″ E |

C1 |

Cork oak forest |

935 |

733 |

Humid |

|

R11 |

Merahna |

36°12'8"N ; 8°9'31" E |

H2 |

Steppe |

280 |

551 |

Semi-arid |

|

R12 |

Oued Medjarda |

37°07′12"N ; 10°3′27"E |

H2 |

Humid environment |

730 |

570 |

Sub-humid |

|

R13 |

Ouled Bechih |

36°20'21"N ; 7°52'19"E |

C1 |

Cork oak forest |

955 |

822 |

Humid |

|

R14 |

Tarja |

36°17'25"N ; 8°03'01"E |

H2 |

Matorral |

782 |

1150 |

Sub-humid |

|

R15 |

Sedrata |

36°7'51"N ; 7°31'57"E |

H2 |

Steppe |

370 |

797 |

Semi-arid |

|

R16 |

Tiffech |

36°11'30"N ; 7°47'10"E |

H2 |

Lawn |

416 |

972 |

Sub-humid |

|

R17 |

Majen Matlag |

36°25'40"N ; 7°55'45"E |

C1 |

Humid environment |

701 |

692 |

Humid |

|

R18 |

M'daourouche |

36°04'29"N ; 7°49'11"E |

H2 |

Steppe |

330 |

753 |

Semi-arid |

12The taxa were identified according to the flora of Battandier (1888–1890), Battandier and Trabut (1895), Maire (1952–1987), Quézel and Santa (1962–1963), Pignatti (1982), and ; Blanca et al. (2009). The nomenclature has been updated according to the synonymic index of North Africa (Dobignard and Chatelain, 2010–2013) and the African Plant Database (APD, 2020). The rarity of taxa was in referrence to the flora of Quézel and Santa (1962–1963) and according to our observations in the field, namely the following statuses: rare (R) and very rare (RR) for non-endemic taxa. For endemic taxa, the classification was as follows: common (C), fairly common (FC), and fairly rare (FR).

13The biological types (Raunkiaer, 1934) of the different taxa has been assigned based on Pignatti (1982), Blanca et al. (2009) and, for some endemics, according to Quézel and Santa (1962-1963).

14Chorological characterization was carried out based in the flora of Andalusia (Blanca et al., 2009), whereas the eight endemic sub-elements followed the flora of Italia (Pignatti, 1982) and the synonymic index of Dobignard and Chatelain (2010–2013).

15Threats and protection status

16The characterization of the on-site threatened species was carried out based on the criteria of rarity by Quézel & Santa (1962-1963), criteria of vulnerability on a global scale by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature in 1997 (Walter & Gillett, 1998), and according to the current red list available (IUCN, 2021). The red list makes it possible to highlight the taxa at the highest risk of extinction and defines the priorities in policies to safeguard and conserve the plant biodiversity. We also considered species with heritage interest protected by Decree No. 03–12 / 12–28, in addition to the non-cultivated plant species protected in Algeria (JORA, 2012) and the synonymic index of North Africa (Dobignard and Chatelain, 2010–2013).

3.1 Scarcity

17Of the 119 species recorded in the study region, nine taxa were quite rare, 55 taxa were rare, 13 taxa were very rare (Table 2), and 14 taxa were rather rare endemics. Indeed, the species observed in the study region seldom had the same heritage value. Additionally, 33 taxa were both endemic and rare (e.g. Bunium crassifolium, Convolvulus durandoi, Dactylorhiza elata, Ophrys subfusca subsp. battandieri). Such relationship between scarcity and endemism was noticeable in our studied flora. Our list includes 28 taxa widely distributed in the national territory (e.g., Anarrhinum pedatum, Stachys duriaei, Bellevalia mauritanica, Rupicapnos numidica), 40 rare to very rare Mediterranean taxa (sensu lato), three rare paleotemperate taxa, and one rare Eurasian taxon.

18Table 2: List of heritage species with their features in the wilaya of Souk Ahras

|

Taxa |

Family |

Biological types |

Chorological types |

Locality |

Habitat |

Scarcity |

|

Achillea ligustica All. |

Asteraceae |

Hem |

Mediterranean |

Mazeraa |

Zeen oak forest |

VR |

|

Allium porrum subsp. polyanthum (Schult. & Schult. f.) Jauzein & J.-M. Tison |

Amaryllidaceae |

Geo |

Eury-Mediterranean |

Ben Attia, Tiffech |

Steppe, lawn |

R* |

|

Althaea hirsuta L. |

Malvaceae |

Th |

Eury-Mediterranean |

Ain senour |

lawn |

R |

|

Ambrosina bassii L. |

Araceae |

Geo |

Subend. Tyrrhenian |

Mazeraa, Ouled Bechih |

Zeen oak forest, cork oak forest |

C |

|

Anacamptis pyramidalis (L.) Rich. |

Orchidaceae |

Geo |

Mediterranean |

Ain Talhi |

Matorral |

R* |

|

Anarrhinum pedatum Desf. |

Plantaginaceae |

Hem |

End. Alg-Tun-Mor |

Ain Zena |

Cliff |

C |

|

Antirrhinum tortuosum Bo ex Vent. |

Plantaginaceae |

Ch |

Mediterranean |

Ain Zena, Hannecha |

Cliff, matorral |

R |

|

Brassicaceae |

Hem |

End Alg-Tun-Mor |

Ain Zena |

Zeen oak forest |

FC |

|

|

Caryophyllaceae |

Th |

End Alg-Tun-Mor |

Ain Zena |

Zeen oak forest |

FC |

|

|

Argyrolobium saharae Pomel |

Fabaceae |

Ch |

End Alg-Mor-Egy |

Ben Attia |

Steppe |

R |

|

Aristolochia paucinervis Pomel |

Aristolochiaceae |

Geo |

Subend. Tyrrhenian |

Ain Trab |

Humid environment |

R |

|

Hem |

End Alg-Tun-Mor |

Ain Talhi |

Matorral |

FR |

||

|

Barnardia numidica (Poir.) Speta |

Asparagaceae |

Geo |

End Alg-Tun-Lib |

Mazeraa, Ouled Bechih, Ain Zena |

Zeen oak forest, cork oak forest, cliff |

C |

|

Bellevalia mauritanica Pomel |

Asparagaceae |

Geo |

End Alg-Tun-Mor-Lib-Egy |

Tarja |

Matorral |

FC |

|

Brassicaceae |

Hem |

End Alg-Tun-Itl |

Ain Talhi, Tiffech |

Matorral, lawn |

FR |

|

|

Brassica procumbens (Poir.) O.E. Schulz |

Brassicaceae |

Th |

End Alg-Tun |

Ain Talhi, Ain Zena, Ben Attia, Ouled Bechih, Mazeraa |

Matorral, cliff, steppe, cork oak forest, zeen oak forest |

C |

|

Bunium crassifolium (Batt.) Batt. |

Apiaceae |

Geo |

End Alg-Tun |

Machrouha, Ain Zena |

Cork oak forest, cliff |

R |

|

Cachrys libanotis L. |

Apiaceae |

Hem |

Mediterranean |

Hannecha |

Matorral |

R |

|

Calamintha menthifolia Host. |

Lamiaceae |

Hem |

Mediterranean |

Mazeraa |

Humid environment |

R |

|

Calendula suffruticosa subsp. boissieri Lanza |

Asteraceae |

Hem |

End Alg-Tun-Mor |

Hannecha, Ain Zena |

Matorral, cliff |

R |

|

Cardopatium amethystinum Spach |

Asteraceae |

Hem |

End Alg-Tun |

Merahna |

Steppe |

FR |

|

Castanea sativa Mill. |

Fagaceae |

Ph |

Mediterranean |

Mazeraa |

Zeen oak forest |

VR |

|

Pinaceae |

Ph |

End Alg-Mor |

Djebel Mcid |

Matorral |

FC |

|

|

Asteraceae |

Th |

End Alg-Mor |

Ben Attia |

Steppe |

FR* |

|

|

Asteraceae |

Hem |

End Alg-Tun-Itl |

Tiffech |

Lawn |

VR |

|

|

Chaerophyllum temulum L. |

Apiaceae |

Hem |

Eurasian |

Majen Matlag |

Humid environment |

R |

|

Convolvulus durandoi Pomel |

Convolvulaceae |

Geo |

End Alg-Tun |

Ain Talhi, Ain zena |

Matorral, cliff |

R |

|

Cosentinia vellea (Aiton) Tod. subsp. vellea |

Sinopteridaceae |

Hem |

Eury-Mediterranean |

Ain Zena |

Cliff |

R* |

|

Cyclamen africanum Boiss. & Reut. |

Primulaceae |

Geo |

End Alg-Tun-Mor |

Mazeraa, Mechrouha, Ouled Bechih, Ain Zena |

Zeen oak forest, cork oak forest, cliff |

C |

|

Cynosurus polybracteatus Poir. |

Poaceae |

Th |

End Alg-Tun |

Mazeraa |

Zeen oak forest |

C |

|

Dactylorhiza elata (Poir.) Soó |

Orchidaceae |

Geo |

End Alg-Tun |

Ain Trab |

Humid environment |

R |

|

Daucus gracilis Steinh. |

Apiaceae |

Th |

End Alg-Tun-Mor |

Mechrouha, Ain Zena |

Cork oak forest, cliff |

FR |

|

Daucus virgatus (Poir.) Maire |

Apiaceae |

Hem |

End Alg-Tun |

Ain senour, Ain Zena |

Matorral, cliff |

R |

|

Apiaceae |

Hem |

End Alg-Tun-Mor-Lib-Mau |

Ben Attia, Merahna |

Steppe |

C |

|

|

Diatelia tuberaria (L.) Demoly |

Cistaceae |

Ch |

Mediterranean |

Mechrouha |

Cork oak forest |

R |

|

Drimia anthericoides (Poir.) Véla & De Bélair |

Asparagaceae |

Geo |

End Alg |

Ain Talhi |

Matorral |

R* |

|

Drimia numidica (Jord. & Fourr.) J.C. Manning & Goldblatt |

Asparagaceae |

Geo |

End Alg-Tun-Spa |

Ain Talhi, Ain senour, Mechroha, Mazeraa, Mare Ain Zena, Ain Zena, Tarja, Djebel Mcid, Ouled Bechih, Ain Trab, Majen Matlag |

Matorral, lawn, Zeen oak forest, cliff, humid environment, cork oak forest |

C |

|

Fabaceae |

Hem |

End-Alg-Tun-Mor-Lib |

Tarja, Tiffech, Ben Attia, Sedrata, M'daourouche |

Matorral, steppe |

C |

|

|

Echinops bovei Boiss. |

Asteraceae |

Hem |

End Alg-Tun-Mor |

Ain Talhi, Ain Zena, Tiffech |

Matorral, cliff, lawn |

C |

|

Eryngium pusillum L. |

Apiaceae |

Hem |

Mediterranean |

Mare Ain Zena, Majen Matlag |

Humid environment |

R |

|

Euphorbiaceae |

Th |

End Alg-Tun-Itl |

Majen Matlag |

Humid environment |

FR |

|

|

Galactites mutabilis Durieu |

Asteraceae |

Th |

End Alg-Tun |

Ain senour, Ain Talhi, Mechroha, Ain zena, Tarja, Ouled Bechih, Tiffech |

Matorral, lawn, cliff, cork oak forest, Zeen oak forest |

FR |

|

Genista ferox (Poir.) Dum. Cours. subsp. ferox |

Fabaceae |

Ph |

End Alg-Tun-Itl |

Ain Talhi, Mechroha, Tarja, Ain Zena, Ouled Bechih, Mazeraa |

Matorral, cork oak forest, cliff, Zeen oak forest |

C |

|

Genista tricuspidata Desf. subsp. tricuspidata |

Fabaceae |

Ph |

End Alg-Tun-Mor |

Mechrouha |

Cork oak forest |

C |

|

Genista ulicina Spach |

Fabaceae |

Ph |

End Alg-Tun |

Ain Talhi, Mechrouha, Ouled Bechih, Ain Zena, Djebel Mcid |

Matorral, cork oak forest, cliff |

FR |

|

Geranium atlanticum Boiss. |

Geraniaceae |

Hem |

End Alg-Tun-Mor |

Djebel Mcid |

Matorral |

C |

|

Geraniaceae |

Th |

Paleotemperate |

Majen Matlag |

Humid environment |

R |

|

|

Geranium dissectum L. |

Geraniaceae |

Th |

Paleotemperate |

Majen Matlag, Ain Trab |

Humid environment |

R |

|

Hedera algeriensis Hibberd |

Araliaceae |

Ph |

End Alg-Tun |

Mazeraa |

Zeen oak forest |

C |

|

Helosciadium crassipes W.J. Koch |

Apiaceae |

Hydr |

Mediterranean |

Mare Ain Zena, Ain Trab, Majen Matlag |

Humid environment |

VR |

|

Hertia cheirifolia (L.) Kuntze |

Asteraceae |

Ph |

End Alg-Tun |

Ben Attia, Merahna, Sedrata, M'daourouche |

Steppe |

C |

|

Fabaceae |

Hem |

End Alg-Tun-Mor |

Ain Zena |

Cliff |

C |

|

|

Hyacinthoides lingulata (Poir.) Rothm. |

Asparagaceae |

Geo |

End Alg-Tun-Mor |

Mechrouha, Mazeraa |

Cork oak forest, Zeen oak forest |

C |

|

Hypericum androsaemum L. |

Hypericaceae |

Ch |

Paleotemperate |

Mazeraa, Ouled Bechih |

Zeen oak forest, cork oak forest |

R |

|

Hypericum montanum L. |

Hypericaceae |

Hem |

Eury-Mediterranean |

Djebel Mcid, Ouled Bechih |

Matorral, cork oak forest |

R |

|

Illecebrum verticillatum L. |

Caryophyllaceae |

Th |

Mediterranean |

Mare Ain Zena |

Humid environment |

VR |

|

Iris unguicularis Poir. |

Iridaceae |

Geo |

End Alg-Tun |

Mechrouha, Mazeraa |

Cork oak forest, zeen oak forest |

C |

|

Brassicaceae |

Th |

End Alg-Tun-Itl |

Djebel Mcid, Tarja |

Matorral |

R |

|

|

Juncus heterophyllus Dufour |

Juncaceae |

Hydr |

Mediterranean |

Mare Ain Zena, Majen Matlag |

Humid environment |

R |

|

Lathyrus latifolius subsp. algericus (Ginzb.) Dobignard |

Fabaceae |

Hem |

End Alg-Tun-Mor |

Ain Talhi |

Matorral |

R* |

|

Lepidium rigidum Pomel |

Brassicaceae |

Hem |

End Alg-Tun |

Ain senour |

Lawn |

FC |

|

Plantaginaceae |

Ch |

End Alg-Tun |

Sedrata |

Steppe |

C |

|

|

Linaceae |

Hem |

End Alg-Tun |

Mechrouha |

Cork oak forest |

C |

|

|

Linaceae |

Th |

End. Alg-Mar-Spa |

Mechrouha |

Cork oak forest |

R |

|

|

Boraginaceae |

Ch |

Mediterranean |

Tarja |

Matorral |

R |

|

|

Brassicaceae |

Th |

End Alg-Tun-Lib |

Sedrata |

Steppe |

FC |

|

|

Mandragora officinarum L. |

Solanaceae |

Hem |

Mediterranean |

Ben Attia |

Steppe |

R |

|

Brassicaceae |

Hem |

End Alg-Tun-Mor |

Ben Attia |

Steppe |

C |

|

|

Hydr |

Mediterranean-Atlantic |

Majen Matlag |

Humid environment |

R |

||

|

Neotinea maculata (Desf.) Stearn |

Orchidaceae |

Geo |

Mediterranean -Atlantic |

Mechrouha |

Cork oak forest |

R |

|

Oenanthe virgata Poir. |

Apiaceae |

Hem |

End Alg-Tun-Mor |

Mare Ain Zena, Oued Medjarda, Majen Matlag |

Humid environment |

C |

|

Ononis angustissima subsp. polyclada Murb. |

Fabaceae |

Ch |

End Alg-Tun-Mar |

Ben Attia |

Steppe |

FC |

|

Ononis aragonensis Asso |

Fabaceae |

Ph |

Ibero-maghrebian |

Sedrata |

Steppe |

VR |

|

Ophioglossum lusitanicum L. |

Ophioglossaceae |

Geo |

Mediterranean |

Mechrouha, Djebel Mcid |

Cork oak forest, matorral |

R |

|

Ophrys ×joannae Maire |

Orchidaceae |

Geo |

End Alg-Tun |

Ain Talhi |

Matorral |

VR* |

|

Ophrys atlantica Munby subsp. atlantica |

Orchidaceae |

Geo |

Ibero-maghrebian |

Sedrata |

Steppe |

FR |

|

Ophrys atlantica subsp. hayekii (H. Fleischm. ex Soó) Soó |

Orchidaceae |

Geo |

Mediterranean |

Sedrata |

Steppe |

R |

|

Ophrys iricolor Desf. subsp. iricolor |

Orchidaceae |

Geo |

Mediterranean |

Ain Talhi, Mechrouha |

Matorral, cork oak forest |

R* |

|

Ophrys marmorata subsp. caesiella (P. Delforge) Véla |

Orchidaceae |

Geo |

Mediterranean |

Hannecha, Mechrouha |

Matorral, cork oak forest |

R* |

|

Ophrys numida Devillers-Tersch. & Devillers |

Orchidaceae |

Geo |

End Alg-Tun |

Ain Talhi, Hannecha, Ain senour |

Matorral, lawn |

R* |

|

Ophrys subfusca subsp. battandieri (E.G. Camus) Kreutz |

Orchidaceae |

Geo |

End Alg-Tun-Mor |

Hannecha, Ain senour |

Lawn, matorral |

R |

|

Orchis anthropophora (L.) All. |

Orchidaceae |

Geo |

Mediterranean-Atlantic |

Tarja |

Matorral |

R* |

|

Orchis laeta Steinh. |

Orchidaceae |

Geo |

End Alg-Tun |

Ain Talhi |

Matorral |

VR* |

|

Orchis patens Desf. subsp. patens |

Orchidaceae |

Geo |

End Alg-Tun-Itl |

Ain Talhi |

Matorral |

VR* |

|

Origanum vulgare subsp. glandulosum (Desf.) Ietsw. |

Lamiaceae |

Ch |

End Alg-Tun |

Djebel Mcid, Hannecha, Ain Zena |

Matorral, cliff |

C |

|

Orobanchaceae |

Geo |

Eury-Mediterranean |

Mazeraa |

Zeen oak forest |

VR |

|

|

Phlomis bovei de Noé |

Lamiaceae |

Hem |

End Alg-Tun-Mar |

Hannecha |

Matorral |

R |

|

Phlomis herba-venti subsp. pungens (Willd.) Maire ex De Filipps |

Lamiaceae |

Hem |

Mediterranean |

Hannecha, Ain Zena |

Matorral, cliff |

R |

|

Hydr |

Mediterranean |

Majen Matlag |

Humid environment |

VR |

||

|

Pistacia atlantica Desf. |

Anacardiaceae |

Ph |

End Alg-Tun-Mor |

Ben Attia, Sedrata |

Steppe |

FC |

|

Plagius grandis (L.) Alavi & Heywood |

Asteraceae |

Ch |

End Alg-Tun |

Ain senour, Tiffech, Ain Zena |

Lawn, cliff |

C |

|

Plagius maghrebinus Vogt & Greuter |

Asteraceae |

Ch |

End Alg-Tun-Mor |

Mazeraa, Mechrouha, Oued Medjarda, Majen Matlag |

Zeen oak forest, cork oak forest, humid environment |

C |

|

Psychine stylosa Desf. |

Brassicaceae |

Th |

End Alg-Tun-Mor |

Ben Attia, Sedrata |

Steppe |

FC |

|

Ranunculaceae |

Th |

Mediterranean |

Majen Matlag |

Humid environment |

R |

|

|

Reichardia tingitana subsp. discolor (Pomel) Jahand. & Maire |

Asteraceae |

Th |

Mediterranean |

Ben Attia |

Steppe |

R |

|

Rhaponticum acaule (L.) DC. |

Asteraceae |

Hem |

Subend. Tyrrhenian |

Ain senour, Tiffech |

Lawn |

C |

|

Romulea ligustica Parl. |

Iridaceae |

Geo |

Mediterranean |

Ain Talhi, Mare Ain Zena, Ain Zena, Ouled Bechih, Djebel Mcid |

Matorral, humid environment, cliff, cork oak forest |

R |

|

Rosmarinus eriocalyx Jord. & Fourr. subsp. eriocalyx |

Lamiaceae |

Ch |

End Alg-Tun |

Hannecha |

Matorral |

R |

|

Rupicapnos numidica (Coss. & Durieu) Pomel |

Papaveraceae |

Hem |

End Alg-Tun |

Ain Zena |

Cliff |

FC |

|

Sambucus ebulus L. |

Adoxaceae |

Hem |

Eury-Mediterranean |

Ain Trab, Oued Medjarda |

Humid environment |

R |

|

Sambucus nigra L. |

Adoxaceae |

Ph |

Eury-Mediterranean |

Oued Medjarda |

Humid environment |

R |

|

Santolina africana Jord. & Fourr. |

Asteraceae |

Ch |

End Alg-Tun-Mor |

Ben Attia, Merahna, M'daourouche |

Steppe |

FC |

|

Scrophularia tenuipes Coss. & Durieu ex Coss. |

Scrophulariaceae |

Hem |

End Alg-Tun |

Mazeraa |

Zeen oak forest |

R |

|

Scutellaria columnae All. subsp. columnae |

Lamiaceae |

Hem |

Mediterranean |

Mazeraa |

Zeen oak forest |

R |

|

Sedum cepaea L. |

Crassulaceae |

Th |

Mediterranean-Atlantic |

Mazeraa, Ouled Bechih |

Zeen oak forest, cork oak forest |

R |

|

Sedum pubescens Vahl |

Crassulaceae |

Th |

End Alg-Tun |

Tarja |

Matorral |

FC |

|

Serapias lingua L. subsp. lingua |

Orchidaceae |

Geo |

Mediterranean |

Ain Talhi, Mare Ain Zena |

Humid environment |

R* |

|

Serapias stenopetala Maire & T. Stephenson |

Orchidaceae |

Geo |

End Alg-Tun |

Mare Ain Zena |

Humid environment |

VR* |

|

Sideritis incana L. subsp. incana |

Lamiaceae |

Ch |

Mediterranean |

Ben Attia, M'daourouche |

Steppe |

R* |

|

Sinapis pubescens subsp. indurata (Coss.) Batt. |

Brassicaceae |

Hem |

End Alg |

Ain Zena, Hannecha, Djebel Mcid |

Cliff, matorral |

R |

|

Smyrnium perfoliatum L. |

Apiaceae |

Hem |

Eury-Mediterranean |

Mazeraa |

Zeen oak forest |

R |

|

Lamiaceae |

Th |

End Alg-Tun |

Hannecha, Ain Zena |

Matorral, cliff |

FC |

|

|

Teucrium atratum Pomel |

Lamiaceae |

Ch |

End Alg-Tun |

Mechrouha |

Cork oak forest |

R |

|

Thymus algeriensis Boiss. & Reut. |

Lamiaceae |

Ch |

End Alg-Tun-Mor |

Hannecha, Ain Zena, Ben Attia, Djebel Mcid, M'daourouche, Ain senour, Tiffech |

Matorral, cliff, lawn, steppe |

C |

|

Thymus munbyanus subsp. coloratus (Boiss. & Reut.) Greuter & Burdet |

Lamiaceae |

Ch |

End Alg-Tun-Mor |

Mecherouha, Ouled Bechih, Ain Zena |

Cork oak forest, cliff |

C |

|

Veronica montana L. |

Plantaginaceae |

Hem |

European |

Pool of Ain Zena |

Humid environment |

VR |

|

Apocynaceae |

Ch |

Mediterranean |

Mechrouha |

Cork oak forest |

R* |

|

|

Viola munbyana Boiss. & Reut. |

Violaceae |

Hem |

End Alg-Tun-Mor |

Djebel Mcid |

Matorral |

FC |

|

Viola riviniana Reich. |

Violaceae |

Hem |

Mediterranean |

Mezeraa, Mechrouha |

Zeen oak forest, cork oak forest |

R |

19End: Endemic, Subend: Subendemic Alg: Algeria; Tun: Tunisia; Mor: Morocco; Lib: Libya; Egy: Egypt; Maur: Mauritania; Itl: Italy; Spa: Spain; Bio. T: biological type; Th: Therophyte; Hem: Hemicryptophyte; Ch: Chamaephyte; Geo: Geophyte; Ph: Phanerophyte; Hydr: Hydrophyte; C: common; F: fairly; R: rare; VR: very rare; (*) modified rarity.

20Of all the taxa studied, ten were threatened or near-threatened as registered on the IUCN Red List (IUCN, 2021), while 13 species were protected by Executive Decree No. 12-03 in Algeria (J.O.R.A, 2012) (see Table 3)

Table 3: List of species protected according to Executive Decree n° 12-03 (JORA, 2012) and/ or evaluated according to IUCN (2021)

|

Taxa |

JORA (2012) |

IUCN (2021) |

|

Argyrolobium saharae Pomel |

P |

|

|

Bunium crassifolium (Batt.) Batt. |

P |

|

|

Cedrus atlantica (Endl.) Carrière ex Manetti |

P |

EN |

|

Convolvulus durandoi Pomel |

P |

NT |

|

Cyclamen africanum Boiss. & Reut. |

P |

|

|

Dactylorhiza elata (Poir.) Soó |

NT |

|

|

Drimia anthericoides (Poir.) Véla & de Bélair |

EN |

|

|

Illecebrum verticillatum L. |

P |

|

|

Juncus heterophyllus Dufour |

NT |

|

|

Mandragora officinarum L. |

P |

|

|

Ononis aragonensis Asso |

P |

|

|

Orchis laeta Steinh. |

NT |

|

|

Orchis patens Desf. subsp. patens |

P |

|

|

Phlomis bovei de Noé |

P |

|

|

EN |

||

|

Pistacia atlantica Desf. |

P |

NT |

|

Scrophularia tenuipes Coss. & Durieu ex Coss. |

P |

NT |

|

Serapias stenopetala Maire & T. Stephenson |

CR |

|

|

Teucrium atratum Pomel |

P |

21P: protected, NT: near-threatened, EN: endangered, CR: critically endangered.

3.2 Biogeographic distribution

We have identified three biogeographic sets in the studied flora:

3.2.1 The Mediterranean set

This set included 39 species (32.77 %) of the flora listed, 27 for the Mediterranean element (sensu stricto), eight for the Eury-Mediterranean connecting element, and four for the Atlantic-Mediterranean connecting element. In this set, the richest families were the Orchidaceae family, with seven taxa, and the Apiaceae and Lamiaceae, with four taxa for each.

3.2.2 Nordic set

This set was represented by three paleotemperate taxa (Hypericum androsaemum, Geranium dissectum and Geranium columbinum), one Eurasian taxon (Chaerophyllum temulum) and one Europaen taxon (Veronica montana L.).

3.2.3 Endemic set

This set was the most important group of the studied flora, with 75 (63.02 %) species. The existent 26 families were of endemic taxa, including the Asteraceae (11 endemics), followed by the Fabaceae and Brassicaceae (nine endemics each). The genus Ophrys was the most diverse with four taxa, followed by the genus Genista with three taxa.

These species belonged to eight sub-elements of endemism:

-

Endemic to Algeria: Two taxa strictly endemic to Algeria were identified in our list (Drimia anthericoides and Sinapis pubescens subsp. indurata);

-

Algerian–Tunisian endemics: The number of Algerian–Tunisian endemic taxa was the highest among all the groups, with 27 species or 36 % of the endemic flora of the region. This number was noteworthy for a region situated at the Tunisian borders;

-

Algerian–Moroccan endemics: This element was composed of two taxa (Cedrus atlantica and Centaurea involucrata);

-

Endemic to Algeria, Tunisia and Italy: Six endemic taxa were noted in Algeria–Tunisia and extending to Italy (Biscutella raphanifolia, Jonopsidium albiflorum, Orchis patens subsp. patens, Euphorbia cuneifolia, Centaurea solstitialis subsp. schouwii, and Genista ferox subsp. ferox);

-

Ibero–Maghrebian: This group had two species (Ononis aragonensis and Ophrys atlantica subsp. atlantica);

-

Endemic to North Africa: The number of taxa in this group was appreciable, with 31 species or 41.33% of the endemic flora of the region. These taxa were often found in at least three countries of North Africa (Algeria, Tunisia, Morocco, and Libya) and sometimes extended to Egypt and Mauritania;

-

Tyrrhenian sub-endemics: Here, three taxa were shared between Numidia, Kroumiria, and the Corso-Sardinian block and/or the Tyrrhenian island group;

-

Betico-Maghrebian endemics (Algeria, Tunisia and Spain or Algeria, Morocco and Spain) were represented by a single taxon.

3.3 Biological distribution

22According to the global list of recorded species, the composition of the biological spectrum showed that the hemicryptophytes, with their 38 taxa (31.93 %), were predominant over other life forms. Geophytes were fairly well represented with 30 species (25.21 %), followed by therophytes, chamaephytes and phanerophytes, with 20 (16.8 %), 17 (14.28 %) and 10 (8.40 %) species respectively. Hydrophytes were poorly represented with only four species (3.36 %).

23The even biological distribution between species was also observed in the identified biogeographic elements, except for the four hydrophytic taxa which were typically Mediterranean.

3.4 Distribution of rare and endemic species according to habitat types

24Matorrals, humid environments, and cork oak forests were the richest in rare species (more than 15 species each), while lawns were the poorest with only seven species.

25Matorral showed most frequent endemism, including 31 taxa, followed closely by cliff ecosystems with 22 taxa. Zeen oak forests, steppes, and cork–oak forests were in an intermediate situation (respectively 14, 17, and 18 species). While, lawns and wetlands were the poorest in endemics (11 and seven species respectively).

26From a bioclimatic point of view, rare and endemic taxa were found in the three bioclimatic stages of the study region, from humid to semi-arid.

3.5 The influence of environmental and edaphic variables on the richness of rare and endemic plants

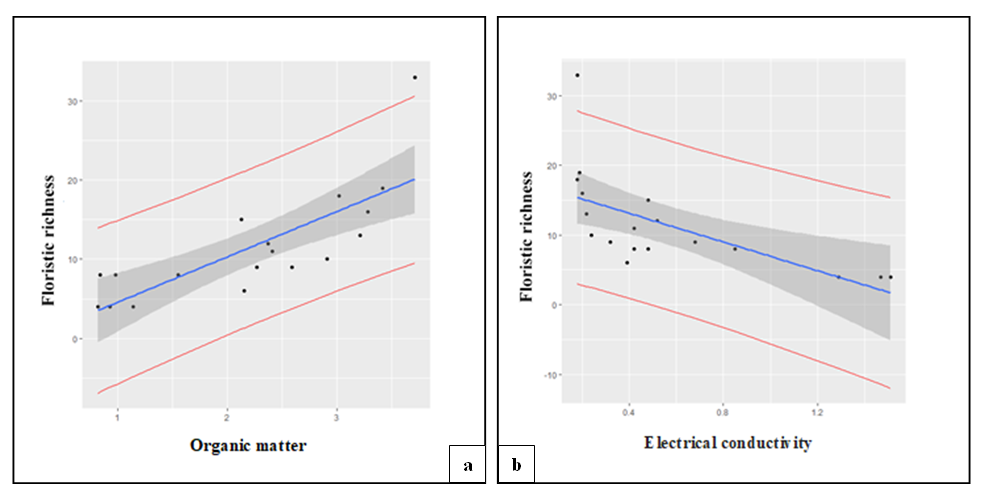

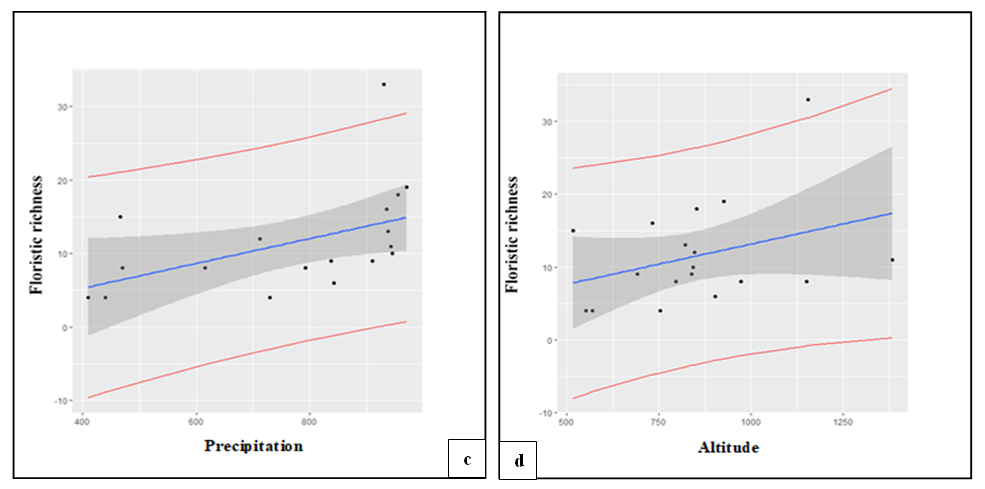

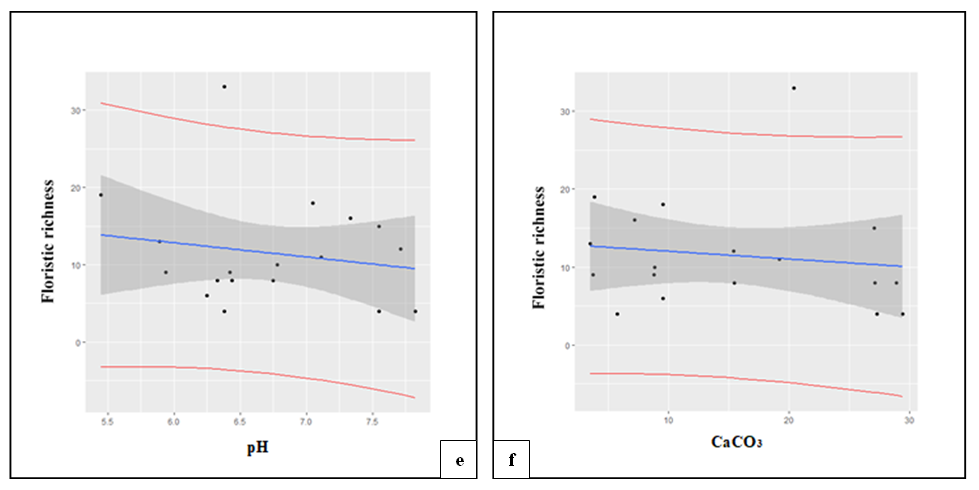

Figure 2: Correlations between the richness in rare and endemic species of the studied localities (black dots), (a) organic matter; (b) electrical conductivity; (c) precipitation; (d) altitude; (e) pH; (f) total limestone

27Among all the studied sites, no significant regressions were observed between specific richness and topographic (altitude), climatic (precipitation), and edaphic variables (pH, electrical conductivity, total limestone, and organic matter). Two variables were significant, namely organic matter (R² = 0.6101; p = 0.0001) and the electrical conductivity (R² = 0.4103; p = 0.0041) (Fig. 2 a & b). Other variables do not seem to influence the floristic composition hence the distribution of rare and endemic plants (Fig. 2 c, d, e & f).

4. Discussion

4.1 Characterization of the flora

The rare and very rare flora of the study area had 119 taxa, i.e. 16.03 % of the flora of the Souk Ahras region, based on 742 species according to the current state of our research (Hamel, Véla & de Bélair, unpublished).

This first inventory of rare and endemic plants in the region of Souk Ahras highlighted the main aspects of this flora (changes in nomenclature, distribution, and type of endemism). Local researchers sometimes tend to neglect these aspects, however they should be considered as a priority in scientific research (Rao, 2004), towards the conservation of the local flora (Véla and Benhouhou, 2007). We observed some introduced individuals of Cedrus atlantica, heighting between 10 to 15 m and particularly present in the humid belt (the summit of Djebel Mcid, altitude 1380 m), and its natural regeneration was ensured by the presence of small plants. The palynological work of Benslama et al. (2010) in the El Kala region (northeast of Algeria) hypothesizes the existence of cedar regional refugium in a relatively mild climate during the last glaciation, collateral to the hypotheses formulated by Terrab et al. (2006). Its presence would have benefited the glacial refugia, further east of its current range in Algeria and Tunisia, from which it disappeared following the contraction during the Holocene (Ben Tiba and Reille, 1982).

The large number of rare and endemic species recorded in the study region have been particularly identified in forest and pre-forest formations (matorrals, cork oak, and zeen oak forests). This richness in taxa accounts for the variability of biogeographical and ecological situations in connection with anthropogenic actions (Barbéro et al., 2001; Yahi et al., 2008).

Quézel (2000) confirmed the richness in endemic species or taxa, which grew on cliffs and rocks, with its disjunct area. Our observations, at an ecological level, concerning the site conditions involving rare and endemic species, were overall in agreement with Quézel and Santa (1962–1963).

The observed plants were very unevenly distributed in the two biogeographical sectors (Quézel and Santa, 1962) of the study region. The Constantine sector (C1) had the highest number of rare and endemic plants (99 species), while the subsector of the highlands of Constantine (H2) was home to 27 high–value taxa. In fact, fluctuations in ecological conditions and the heterogeneity of habitats are determining factors of flora richness of these biogeographical zones (Touati et al., 2020).

Some species of C1 and H2 were not reported previously in “The flora of Algeria”, e.g., Antirrhinum tortuosum, Argyrolobium saharae, Aristolochia paucinervis, Bunium crassifolium, Calamintha menthifolia, Castanea sativa, Chaerophyllum temulum, Daucus virgatus, Galactites mutabilis, Genista ulicina, Heliosciadium crassipes, Mandragora officinarum, Ononis angustissima subsp. polyclada, Ophrys atlantica subsp. hayekii, Orchis laeta, Orchis patens subsp. patens, Phlomis bovei, Pilularia minuta, Reichardia tingitana subsp. discolor, Scrophularia tenuipes, Smyrnium perfoliatum, Teucrium atratum, Veronica montana and Viola riviniana. All these new observations in the two biogeographical sectors of the region encouraged us to carry out a meticulous search for taxa, which might have escaped in previous investigations, as in the case of the 16 taxa illustrated by Edough Peninsula of Boulemtafes et al. (2018) and the study of Pteris vittata L. in February 2016 in Western Numidia (Hamel et al., 2020a). In a more global context, the presence of these plants in other biogeographical sectors suggested the requirement of a revision of the Algerian flora (cf. eflora Maghreb).

Other rare and endemic taxa, such as Euphorbia helioscopia subsp. helioscopioides (Loscos & C. Pardo) Nyman and Odontites discolor Pomel, were found in our region. They seem to have previously disappeared or declined in the same habitat (Battandier and Trabut, 1890; Maire, 1928; Quézel and Santa, 1963). In some cases, natural environments have been so disrupted by other elements, such as fires, overgrazing, and urban development, that some sites were destroyed Considering the established uncertainity, additional surveys could be carried out in the future.

Mandragora officinarum, defined as rare and endangered in Quézel and Santa (1962), has been exclusive to the Kabylias-Numidia sector (K) and the Algerian coastal sub-sector (A1) (site not found until now) (see Hanifi et al., 2007). We have observed it on the steppes of Ben Attia, which seems very rare and new for the subsector H2 of the Constantine highlands (Touati et al., 2020).

We have noticed that endemism status of some taxa had been changing, such as for Genista ferox subsp. ferox, previously mentioned as strictly endemic to the Maghreb by Quézel and Santa (1962) and recently retained as endemic in Algeria, Tunisia, Morocco, and Sardinia by CJB (2020). This is the case of Aristolochia paucinervis, previously mentioned in the flora of Quézel and Santa (1962-1963) as Mediterranean, while APD (2020) considers this as a Tyrrhenian subendemic. The changes in the chorological type of these species can be explained by the increased botanical investigations, either in the Mediterranean or in North Africa. Such investigations aim at listing biodiversity and monitor its evolution, either expanding the floristic lists by adding taxa or narrowing them by removing others (Gordo and Hadjadj-Aoul, 2019).

4.2 Taxonomic, biological and biogeographic diversity

28A total of 119 remarkable taxa (endemic, rare, threatened, or protected) of angiosperms and pteridophytes were reported in our study sites. All these listed species are factors of a great conservation value, either for heritage reasons or for their risk of extinction (Pimm et al., 1988; Gaston et al., 1998).

29The highest degree of endemicity corresponds to Asteraceae (11 taxa), Brassicaceae (nine taxa), Fabaceae (nine taxa), Orchidaceae (eight taxa) and Lamiaceae (seven taxa). These results corroborate the conclusions by Le Houérou (1995), who stated that the Asteraceae, Fabaceae, and Lamiaceae are the richest families in endemics in North Africa, and by Quézel (1978) regarding the Lamiaceae family. The richness of the local flora in Orchids in the study area confirmed the observations made by Boukehili et al. (2018). This resemblance is the result of their common history from which resulted a very homogeneous biogeographical unit (Quézel, 1964).

30The relative number of endemic taxa sensu lato presented in this work was 63.05%. However, it is comparably very high to that stated by Hamel et al. (2013) for the Edough peninsula (47%), Djebbouri and Terras (2019) for the forest formations of Saïda (North-West Algeria) (08.81%), Medjahdi et al. (2009) for the Traras mountains (19.71%) and Miara et al. (2017) for the Tiaret region (38%). This richness was the result of climate diversity, exposures, substrates, and orography with a mountain range, which culminates at 1405 m (Djebel Mcid), 1230m (Saïda),1008m (Edough) and875m (Tarras). As stated by Verlaque et al. (1997), the Mediterranean endemism is mainly concentrated in mountain ranges and islands.

31We have identified two restricted endemic species (endemic to Algeria). These taxa were both rare and endemic “taxa classified as of high heritage value”, Drimia anthericoides was on the red list of the IUCN (Véla and de Bélair, 2017), as “endangered”. These are:

32- Drimia anthericoides: endemic to northeastern Algeria seemed to be a new species rank to the national flora (Véla et al., 2016). It is a critical taxon considered as a variety of Urginea maritima (L.) Baker (Maire, 1958; Quézel and Santa, 1962). Nevertheless, it differs from other aggregate species/varieties of Charybdis maritima (L.) Speta [= Urginea maritima] in terms of characters of flowers, fruits, bulbs, leaves, and by ploidy level (Véla et al., 2016). A review of the sites on the Tunisian side would still be beneficial in order to verify any past confusion. However, the observation site is on private land, thus potentially threatened by agriculture and/or grazing.

33- Sinapis pubescens subsp. indurata: the diversity of the genus Sinapis in Algeria is remarkable with eight species and subspecies, of which two are endemics (S. pubescens subsp. aristidis and subsp. indurata) (Dobignard and Chatelain, 2011). This taxon has been previously reported in Souk Ahras in three different localities: Mont Mahrouf by H. de Perraudière (without specifying a date?) and by Reboud (without date?) in Sgao and Djebel Mcid (Maire, 1965). We have consulted all the plates of APD (2020) labeled “Sinapis pubescens subsp. indurata” of which three plates “MPU009015, MPU009016 and S-G-9038” collected by H. de Perraudière (7/16/1861) related to our species.

34The Algerian–Tunisian endemism represented the majority of endemic taxa recorded with 27 species. However, these border endemics correspond less to specialized areas with highly endemic species, than to the vast biogeographical zones, where endemic species are locally less rare and even abundant (Véla and Benhouhou, 2007; Hamel et al., 2013).

35Our study area had 26 endemic species from Northwest Africa, with at least three countries (Algeria, Morocco, Tunisia and/or Libya).

36The presence of Tyrrhenian endemics in the flora studied (three taxa) could explain the past terrestrial connections of the Algerian Tellian and Tunisian coast with Tyrrhenia (Quézel, 1964; Hamel and Boulemtafes, 2017; Hamel et al., 2020b). The importance of the Mediterranean (sensu lato) element of the rare flora in the study area (40 species, or 31.61 %) was in agreement with Quézel (1983), who found a greater number of Mediterranean-type species (40.13 %) in the North African flora.

37Two plants were classified as flagship species in the Algerian (IPA), called "El Kala 2": Scrophularia tenuipes and Scutellaria columnae. These two plants, along with Convolvulus durandoi, Orchis laeta, Phlomis bovei, and Drimia anthericoides, are found in a restricted area (occurrence between 100 and 5,000 km²). Additionally, Dactylorhiza elata and Serapias stenopetala, two restricted endemic species were found in less than 100 km² (Yahi et al., 2012).

38Some plants, including the strict endemic Sinapis pubescens subsp. indurata, which are rare nationally but locally common, exist in the study area. In general, this rarity is due to the limited extent of the subhumid climate in Algeria.

39The studied flora was dominated by hemicryptophytes (31.09 %), which prefer fairly stable environments and soil rich in organic matter (Kazi Tani et al., 2010). This suggested that the rainfall, the weakness of the light, and the pastures of the undergrowth favored the development of hemicryptophytes. Barbéro et al. (2001) reported that their abundance in Maghreb countries is due to the presence of organic matter and moisture. In addition, the dominance of hemicryptophytes has also been confirmed in the rare and endemic flora of the Edough Peninsula (Hamel et al., 2013). Geophytes were also well represented with 30 species. Their rate is relatively higher in a forest environment than in lawns and steppe areas where they tend to fade (Barbéro et al., 1981). Chamaephytes were represented by 20 species or 16.8 % of the studied flora. They would be well adapted to the phenomenon of soil aridification as they can develop variants to drought (Floret et al., 1990). On the other hand, in certain regions, the encrusted soils are thin and the continuous calcareous crust which covers them does not allow any plant rooting (Boudjadja et al., 2010). Gamoun et al. (2011) claim that sandy soil is more productive due to increased water impermeability than limestone soil, which reduces water penetration.

4.3. Threats and conservation measures

40Due to insufficient documentation and studies, 109 of the rare and endemic plants in our study area and elsewhere in Algeria have not been yet assessed, according to the criteria established by IUCN (2021). Protection is urgent to a total of 106 rare and endemic species. Without it, they are threatened with extinction, especially since they are not placed on the list of protected plant species in Algeria (JORA, 2012).

41The rare and endemic flora of the Souk Ahras region is undergoing an alarming degradation. Additionally, anthropogenic activities, especially fires, overgrazing, and uncontrolled exploitation of species known for their therapeutic virtues (e.g. Origanum vulgare subsp. glandulosum, Thymus algeriensis, Rosmarinus eriocalyx subsp. eriocalyx, Mandragora officinarum, Thymus munbyanus subsp. coloratus, Deverra scoparia subsp. scoparia, and Santolina africana) stand as threats to this flora. Other taxa are heavily consumed (Allium porrum subsp. polyanthum, Bunium crassifolium, Echinops bovei, Rhaponticum acaule, and Romulea ligustica) or used as ornamentals (e.g. Hedera algeriensis, Sambucus nigra, Iris inguicularis, and Cyclamen africanum) (see Sakhraoui, 2021).

Based on our study we propose the main short-term conservation solutions below:

- Habitat protection, including populations of threatened species where conservation problems are most critical (Cedrus atlantica, Drimia anthericoides, Pilularia minuta, and Serapias stenopetala) by creating “micro-reserves”, thus providing sustainable conservation and leading to a representative natural habitat (Laguna et al., 2004).

- Modeling the distribution of each species for its reintroduction into its natural habitat or into new suitable areas, according to the species distribution models.

- Revise and update the list of protected plant species in Algeria according to the criteria of endemism, rarity, and threats, as both rare and endemic species have high conservation value.

5. Conclusion

Our analysis based on the current knowledge of the rare and endemic flora of the wilaya of Souk Ahras revealed a significant specific richness (119 species), characterized by 75 endemic species and 77 rare species. This regional endemic flora is hardly known as a large area of the study region and remains very poorly explored. The entire area located at the Algerian–Tunisian border, the steppes of Macrochloa tenacissima (L.) Kunth, and Artemisia herba-alba Asso, located in the south of the region, deserve to be thoroughly explored. Likewise, the relationship between scarcity and endemism was remarkable. Half endemic taxa in a broad sense were rare and listed on the protected plant species in Algeria, while the majority (more than a hundred) are not protected. Hence, it is necessary to protect these species in accordance to endemicity and rarity.

6. References

42AFNOR, 1999, Qualité des sols – vocabulaire. Partie 2. Termes et définitions relatifs à l’échantillonnage. Paris.

43Allem, M., Hamel, T., Tahraoui, C., Boulemtafes, A. and Bouslama, Z., 2017, Diversité floristique des mares temporaires de la région d’Annaba (Nord-Est Algérien). International Journal of Environmental Studies, 75(3), 405-424.

44Amirouche, R. and Misset, M. T., 2009, Flore spontanée de l’Algérie: différenciation éco-géographique des espèces et polyploïdie. Cahier d’Agriculture, 18, 474-480.

45Anderson, S., 1994, Area and endemism. The Quarterly Review of Biology, 69, 451–471.

46APD: African Plants Database, 2020, Geneve: Conservatoire et Jardin botaniques de la Ville de Genève; Pretoria (SA): South African National Biodiversity Institute. http:// www.ville-ge.ch/musinfo/bd/cjb/africa.

47Barbéro, M., Loisel, R., Médail, F. and Quézel, P., 2001, Signification biogéographique et biodiversité des forêts du bassin méditerranéen. Bocconea, 13, 11-25.

48Barbéro, M., Quézel, P. and Rivas-Martinez, S., 1981, Contribution à l’étude des groupements forestiers et pré-forestiers du Maroc. Phytoceonologia, 9, 311-412.

49Battandier, J.A., 1888-1890, Flore de l’Algérie: dicotylédones. A. Jourdan (ed.), Alger.

50Battandier, J.A. and Trabut, L., 1895, Flore d’Algérie, contenant la description de toutes les plantes signalées jusqu'à ce jour comme spontanées en Algérie et catalogue des plantes du Maroc: Monocotylédones. A. Jourdan (ed.), Alger.

51Ben Tiba, B. and Reille, M., 1982, Recherches pollenanalytiques dans les montagnes de Kroumirie (Tunisie septentrionale) : Premiers résultats. Ecologia Mediterranea, Marseille, VII(4), p. 75-86.

52Benhouhou, S., Yahi, N. and Véla, E., 2018, Algeria (chapter 3 "Key Biodiversity Areas (KBAs) for plants in the Mediterranean region"), UICN 53-60.

53Benslama, M., Andrieu-Ponel, V., Guiter, F., Reille, M., de Beaulieu, J-L., Migliore, J. and Djamali, M., 2010, Pollen analysis from two littoral marshes (Bourdim and Garaat El-Ouez) in the El-Kala wet complex (North-East Algeria). Lateglacial and Holocene history of Algerian vegetation. Comptes Rendus Biologies, 333(10), 744-754.

54Blanca, G., Cabezudo, B., Cueto, M., Lopez, C. F. and Torres, C. M., 2009, Flora Vasculair de Andalucía Oriental, 1-4. – Seville.

55Blondel, J., Aronson, J., Bodiou, J.Y., and Boeuf, G., 2010, The Mediterranean Region: Biological Diversity in Space and Time (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

56Boudjadja, A., Kaddour, B.H. and Pauc, H., 2010, Increasing the value of surface water storage for protected wildlife, particularly the emblematic Cuvier’s Gazelle, in Mergueb Reserve (M’sila, Algeria). Revue d’Ecologie la Terre et la Vie, 65(3), 243−253.

57Boudy, P., 1955, Economie forestière nord-africaine. Tome IV, Description forestière de l'Algérie et de la Tunisie. Ed. Larose, Paris.

58Boukehili, K., Boutabia, L., Telailia, S., Menaa, M., Tlidjane, A., Maazi, M.C., Chefrour, A., Saheb, M. and Véla, E., 2018, Les orchidées de la wilaya de Souk Ahras (Nord-est Algerien): inventaire, écologie, répartition et enjeux de conservation. Revue d’Ecologie (Terre et Vie), 73 (2), 167-179.

59Boulemtafes, A., Hamel, T., de Bélair, G. and Véla, E. 2018, Nouvelles données sur la distribution et l’écologie de seize taxons végétaux du littoral de la péninsule de l’Edough (Nord–Est algérien). Bulletin de la Société linnéenne de Provence, 69, 59-76.

60Braun-Blanquet, J., Roussine, N. and Nègre, R., 1952, Les groupements végétaux de la France méditerranéenne. Dir. Carte Group. Vég. Afr. Nord, CNRS.

61Cañadas, E. M., Giuseppe, F., Peñas, J., Lorite, J., Mattana, E. and Bacchetta, G., 2014, Hotspots within hotspots: Endemic plant richness, environmental drivers, and implications for conservation. Biological Conservation, 170, 282–291.

62Communication de l'Office National de la Météorologie (CONM), station: Souk Ahras, période (1990- 2020).

63de Bélair G., Véla, E. and Boussouak, R., 2005, Inventaire des orchidées de la Numidie (NE Algérie) sur vingt années. Journal Europaischer Orchideen, 37, 291-401.

64Djebbouri, M. and Terras, M., 2019, Floristic diversity with particular reference to endemic, rare, or endangered flora in forest formations of Saida (Algeria). International journal of Environment Studies, 1, 1–8.

65Dobignard, A. and Chatelain, C., 2010-2013, Index synonymique de la flore d’Afrique du Nord 5. [Eds des Conservatoire et jardin botaniques de Genève].

66Domina, G., Bazan, G., Campisi, P. and Greuter, W., 2015, Taxonomy and conservation in higher plants and bryophytes in the Mediterranean area. Biodiversity Journal, 6, 197- 204.

67Floret, C.H., Galan, M.J., Le Floc H., Orshan, G. and Romane, F., 1990, Growth forms and phenomorphology traits along an environmental gradient: tools for studying vegetation. Journal of Vegetation Science, 1, 71-80.

68Gamoun, M., Tarhouni, M., Ouled Belgacem, A., Hanchi, B. and Neffati, M., 2010, Effects of grazing and trampling on primary production and soil surface in North African rangelands. Ekológia (Bratislava), 29(2), 219−226.

69Gaston, K.J., 1991, How large is a species geographic range? Oikos, 61(3), 434–438.

70Gaston, K. J., Blackburn, T. M. and Spicer, J. I., 1998, Rapoport’s rule: time for an epitaph? Trends Ecology Evolution, 13, 70-74.

71Ghrabi-Gammar, Z., Daoud-Bouattour, A., Ferchichi, H., Gammar, AM., Muller, SD., Rhazi, L. and Ben Saad-Limam, S., 2009, Flore vasculaire rare, endémique et menacée des zones humides de Tunisie. Revue d’Ecologie (Terre Vie), 64, 19-40.

72Gordo, B. and Hadjadj-Aoul, S., 2019, L’endémisme floristique algéro-marocain dans les monts des Ksour (Naâma, Algérie). Flora Mediterranea, 29, 129-142.

73Hamaidia H. et Berchi S. 2018, Etude systématique et écologique des Moustiques (Diptera: Culicidae) dans la région de Souk-Ahras (Algérie). Entomologie faunistique, 71, 13-27.

74Hamel, T., Seridi, R., de Bélair, G., Slimani, A. R. and Babali, B., 2013, Flore vasculaire rare et endémique de la péninsule de l’Edough (Nord–Est algérien). Revue Synthèse des Sciences et de la Technologie, 26, 65–74.

75Hamel, T. and Boulemtafes, A., 2017, Découverte d’une endémique tyrrhénienne Soleirolia soleirolii (Urticaceae) en Algérie (Afrique du Nord). Flora Mediteranea, 27, 185–193.

76Hamel, T., de Bélair, G., Slimani, AR., Boutabia, L. and Telailia, S., 2020a, Nouvelle station de Pteris vittata L. (Pteridaceae) en Numidie (Algérie orientale). Acta Botanica Malacitana, 45, 1-3.

77Hamel, T., Saci, A. and de Bélair, G., 2020b, Redécouverte d’un subendémique tyrrhénien, Tuberaria acuminata (Viv.) Grosser, en Numidie (Nord – Est algérien), Bull. Soc. linn. Provence, 71, 243-247.

78Hanifi N., Kadik L. et Gittonneau G.G. 2007, Analyse de la végétation des dunes littorales de Zemmouri (Boumerdes, Algérie). Acta Bot. Gallica, 154, 235-249.

79Huang, J., Huang, J., Liu, C., Zhang, J., Lu, X. and Ma, K., 2016, Diversity hotspots and conservation gaps for the Chinese endemic seed flora. Biological Conservation, 198, 104–112.

80IUCN, 2021, IUCN Red List of Threatened Plants. Version 2021-1. http://www.iucnredlist.org

81J.O.R.A., 2012, Décret exécutif du 18 janvier 2012, complétant la liste des espèces végétales non cultivées et protégées. Journal officiel de la république algérienne. 3-12/12 du 18-01-2012. 12–38.

82Kazi Tani, Ch., Le Bourgeois, T. and Munoz, F., 2010, Aspects floristiques des adventices du domaine phytogéographique oranais (Nord-Ouest algérien) et persistance d’espèces rares et endémiques. Flora Mediterranea, 20, 29-46.

83Laguna, E., Deltoro, V.I., Pérez-Botella, J., Pérez-Rovira, P., Serra, L., Olivares, A. and Fabregat, C., 2004, The role of small reserves in plant conservation in a region of high diversity in eastern Spain. Biological Conservation, 119(3), 421–426.

84Le Houérou, H.N., 1995, Considérations biogéographiques sur les steppes arides du Nord de l’Afrique. Sécheresse, 6, 167-182.

85Maire R., 1928, Origine de la flore des montagnes de l'Afrique du Nord. Mém. Soc. Biogéog., 2, 187-194.

86Maire, R., 1952-1987, Flore de l’Afrique du Nord (Maroc, Algérie, Tunisie, Tripolitaine, Cyrénaïque et Sahara). 16 vols, Lechevalier, Paris.

87Mansouri, S., Miara M.D. and Hadjadj-Aoul, S., 2018, Etat des connaissances et conservation de flore endémique dans la région d’Oran (Algérie occidentale). Acta Botanica Malacitana, 43, 23-30.

88Mathieu, C and Pieltain, F., 2003, Analyse chimique des sols. Ed. Tec et doc. Lavoisier, Paris, 292 p.

89Médail, F. and Diadema, K., 2006, Biodiversité végétale méditerranéenne et anthropisation: approches macro et micro-régionales. Annales de Géographie, 651, 618–640.

90Medjahdi, B., Ibn Tattou, M., Barkat, D. and Benabedli, K., 2009, La flore vasculaire des Monts des Traras. Acta Botanica Malacitana, 34, 57-75.

91Miara, M.D., Ait Hammou, M., Rebbas, K. and Bendif, H., 2017, Flore endémique, rare et menacées de l’Atlas tellien occidental de Tiaret (Algérie). Acta Botanica Malacitana, 42 (2), 271-285.

92Miara, M.D., Ait Hammou, M., Dahmani, W., Negadi, M. and Djellaoui, A., 2018, Nouvelles données sur la flore endémique du sous-secteur de l’Atlas tellien Oranais “O3” (Algérie occidentale). Acta Botanica Malacitana, 43, 63-69.

93Mittermeier, R.A., Gil, P.R., Hoffmann, M., Pilgrim, J., Brooks, T., Mittermeier, C.G., Lamoreux, J. and Da Fonseca, G.A.B., 2004, Hotspots Revisited: Earth’s Biologically Richest and Most Endangered Terrestrial Ecoregions. Chicago.

94Morrone, J.J., 2018, The spectre of biogeographical regionalization. Journal of Biogeography, 45, 282–288,

95Myers, N., Mittermeier, R.A., Mittermeier, C.G., da Fonseca, G.A.B. and Kent, J., 2000, Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature, 403, 853–858. https://doi.org/10.1038/35002501

96Myers, N., 2003, Biodiversity hotspots revisited. BioScience, 53(10), 916–917.

97Pignatti, S., 1982, Flora d’Italia, 3 Vol. Bologna.

98Pimm, S.L., Jones, H.L., and Diamond, J., 1988, On the risk of extinction. The American Naturalist, 132(6), 757–785.

99Primack, R.B., Sarrazin, F. and Lecomte, J., 2012, Biologie de la conservation. Dunod, Paris.

100Quézel, P., 1964, L’endémisme dans la flore de l’Algérie. Comptes Rendus de la Société de biogéographie, 361, 137-149.

101Quézel, P., 1978, Analysis of the flora of Mediterranean and Saharan Africa. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden, 65, 479-537.

102Quézel, P., 1983, Flore et végétation de l’Afrique du Nord, leur signification en fonction de l’origine, de l’évolution et des migrations des flores et structures de végétation passées. Bothalia, 14, 411–416.

103Quézel, P., 1995, La flore du bassin méditerranéen, origine, mise en place, endémisme. Ecologia Mediterranea, 22(1-2), 19-39.

104Quézel, P., 1998, La végétation des mares transitoires à Isoetes en région méditerranéenne, intérêt patrimonial et conservation. Ecologia Mediterranea, 24, 111-117.

105Quézel, P., 2000, Réflexions sur l’évolution de la flore et de la végétation au Maghreb méditerranéen. Ibis Press, Paris, 117 ppQuézel, P. and Santa, S., 1962-1963, Nouvelle flore de l’Algérie et des régions désertiques méridionales. CNRS (Ed). Paris, 2 vols.

106R Development Core Team, 2013, R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for statistical computing, Vienna, Austria. [http://www.R-project.org.]

107Rao, M.K., 2004, The importance of botanical nomenclature and synonymy in taxonomy and biodiversity M. K. Current Science, 87, 602–606.

108Raunkiaer, C., 1934, The life forms of plants and statistical plant geography. Oxford University Press, London.

109Riemann, H. and Ezcurra, E., 2005, Plant endemism and natural protected areas in the peninsula of Baja California, Mexico. Biological Conservation, 122, 141–150.

110Sakhraoui, N., 2021. La flore horticole cultivée dans l’Est algérien : état des lieux et stratégies de gestion durable. Thèse de Doctorat en Physiologie Végétale. Thèse de Doctorat, Université Mohamed El Cherif Messaadia, Algérie.

111Terrab, A., Paun, O., Talavera, S., Tremetsberger, K., Arista, M. and Stuessy, T.F., 2006, Genetic diversity and population structure in natural populations of Maroccan cedar (Cedrus atlantica; Pinaceae) determined with cpSSR markers. American Journal of Botany, 93(9), 1274–1280.

112Touati, L., Hamel, T. and Meddad-Hamza, A., 2020, Sur la présence d’Atriplex canescens (Amaranthaceae) en Algérie: écologie, taxonomie et biogéographie. Flora Mediterranea, 30, 33-38.

113Véla, E. and Benhouhou, S. 2007, Évaluation d’un nouveau point chaud de biodiversité végétale dans le bassin méditerranéen (Afrique du Nord). Comptes Rendus Biologies, 330, 589-605.

114Véla, E., de Bélair, G., Rosato, M. and Rosselló, J., 2016, Taxonomic remarks on Scilla anthericoides Poir. (Asparagaceae, Scilloideae), a neglected species from Algeria. Phytotaxa, 288 (2), 154–160.

115Véla, E. and de Bélair, G., 2017, Charybdis anthericoides. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2017:e.T111272454A111273406. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017

116Verlaque, R., Médail, F., Quézel, P. and Babinot, J.F., 1997, Endémisme végétal et paléogéographie dans le bassin méditerranéen. Geobios, 21, 159-166.

117Yahi, N., Djellouli, Y and de Foucault, B., 2008, Diversités floristique et biogéographique des cédraies d’Algérie. Acta Botanica Gallica, 155(3), 389-402.

118Walter, K.S. and Gillett, H.J. 1998, 1997 IUCN red list of threatened plants. Compiled by the World Conservation Monitoring Centre. IUCN – the World Conservation Union. Gland, Switzerland & Cambridge, UK.

119Yahi, N., Véla, E., Benhouhou, S., de Bélair, G. and Gharzouli, R., 2012, Identifying Important Plants Areas (Key Biodiversity Areas for Plants) in northern Algeria. Journal of Threatened Taxa, 4, 2453-2765.

120Zedam, A., 2015, Etude de la flore endémique de la zone humide du Chott El Hodna, inventaire et préservation. Thèse de Doctorat en écologie, Université de Sétif, Algérie.

121Declaration of Competing Interest

122No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

123ORCID : https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9770-6805

Appendix A

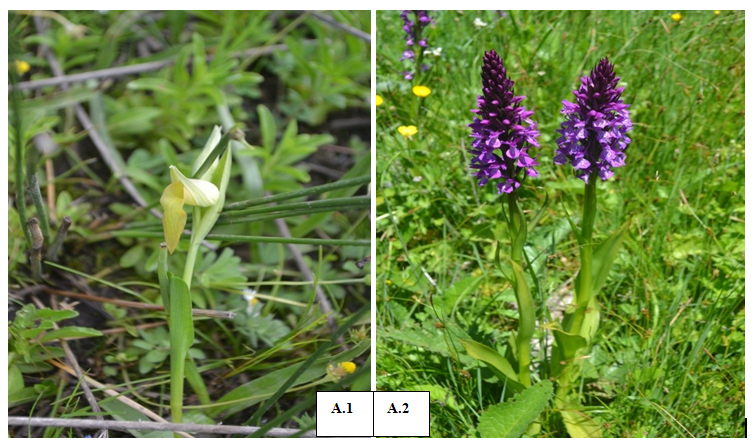

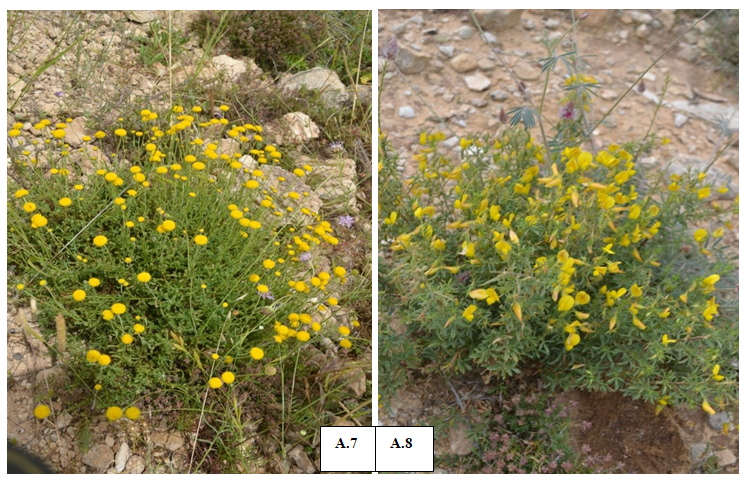

Some rare and endemic species from the wilaya of Souk Ahras

(All the photos: Hamel T., except the photo A.5: de Bélair G.).

|

A.1. Serapias stenopetala Maire & T. Stephenson |

A.9. Sideritis incana L. subsp. incana |

|

A.2. Dactylorhiza elata (Poir.) Soo |

A.10. Argyrolobium saharae Pomel |

|

A.3. Mandragora officinarum L. |

A.11. Orchis laeta Steinh |

|

A.4. Sinapis pubescens L. subsp. indurata (Coss.) Batt |

A.12. Calendula suffruticosa subsp. boissieri Lanza |

|

A.5. Drimia anthericoides (Poir.) Véla & De Bélair |

A.13. Scutellaria columnae All. subsp. columnae |

|

A.6. Aristolochia paucinervis Pomel. |

A.14. Convolvulus durandoi Pome |

|

A.7. Santolina africana Jord. & Fourr. |

A.15. Chaerophyllum temulum L. |

|

A.8. Ononis angustissima subsp. polyclada Murb. |

A.16. Orobanche rapum-genistae Thuill. |