- Accueil

- Volume 94 - Année 2025

- No 1

- Further Considerations of the Provenance of the Rocourt Tephra: Volcanic Mafic Minerals and Age

Visualisation(s): 891 (8 ULiège)

Téléchargement(s): 469 (2 ULiège)

Further Considerations of the Provenance of the Rocourt Tephra: Volcanic Mafic Minerals and Age

Document(s) associé(s)

Version PDF originaleRésumé

Le Téphra de Rocourt est une retombée de cendre volcanique qui a été découverte en Belgique, il y a trois quarts de siècle. Depuis lors, toutes les recherches destinées à découvrir son volcan émetteur ont été vaines. Deux volcans de l’Eifel occidental ont été cités, à savoir le Dreiser Weiher et le Pulvermaar, mais il a été démontré par la composition chimique des pyroxènes qu’ils sont incompatibles avec le Téphra de Rocourt (Juvigné et al., 2024, DOI: 10.1007/s00445-024-01756-2). Le présent travail présente des arguments supplémentaires qui supportent cette conclusion ; ils relèvent de la comparaison des associations de minéraux mafiques volcaniques des trois parties impliquées. Par ailleurs, les détails de l’étude stratigraphique qui ont conduit à estimer l’âge du Téphra de Rocourt entre 70 et 80 ka sont rapportés, de façon à élargir la tolérance avec d’éventuelles datations de volcans de l’Eifel ou d’ailleurs.

Abstract

The Rocourt Tephra (RT) is a pyroclastic fallout deposit that was discovered in Belgium three-quarters of a century ago. Since then, the search for its source volcano has been in vain. Recently, however, two volcanoes of the West Eifel Volcanic Field have been put forward, namely the Dreiser Weiher and the Pulvermaar, but it has been shown by the geochemical fingerprints of associated pyroxenes that neither of them is compatible with the RT (Juvigné et al., 2024, DOI: 10.1007/s00445-024-01756-2). We present here additional arguments that support this conclusion. They arise from the comparison of volcanic mafic mineral associations of the RT and the Dreiser Weiher and Pulvermaar tephras. Furthermore, details of the stratigraphic study that led to the age estimate of between 70 and 80 ka for RT are reported, in order to widen the scope for determining the ages of volcanoes or tephras in the Eifel Volcanic Field (or elsewhere).

Table des matières

Received: 24 December 2024 – Accepted 20 March 2025

This work is distributed under the Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 Licence.

1. Introduction

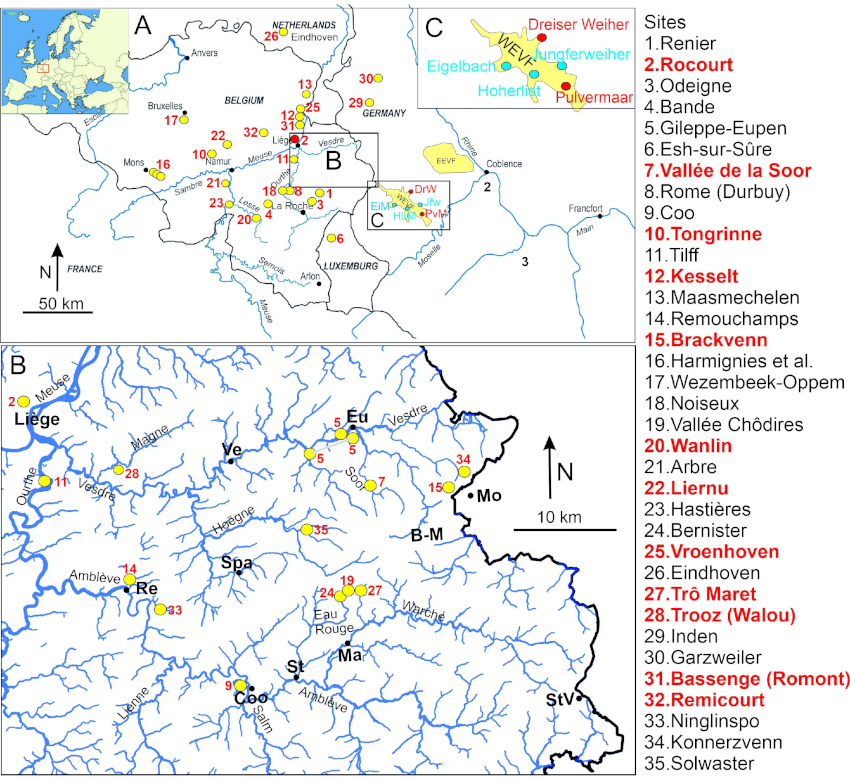

1The enstatite bearing volcanic ash deposit (now known as Rocourt Tephra, RT, see below) was discovered in a dispersed state (i.e., as a cryptotephra) in reworked deposits of Upper Belgium (Gullentops, 1952; Tavernier and Laruelle, 1952), then in a paleosol of the Eemian–Weichselian transition of the Rocourt loess stratotype (Gullentops, 1954). Since then, it has been found in about 35 sites in Belgium, the Grand-Duchy of Luxembourg, the Netherlands and the Lower Rhine Bay/Germany (Fig. 1; Table 1).

Figure 1: Location of sites where the volcanic mafic minerals (vmm) of the Rocourt Tephra (RT) have been identified as well as some localities where enstatite has been recognized as traces in various associations. Explanation: the numbers referring to localities correspond to the relevant literature references listed in Table 1 ; sites in bold and red font are of major interest, providing mineralogical and/or chemical and/or stratigraphical data. Abbreviations: WEVF = West Eifel Volcanic Field; PvM = Pulvermaar; DrW = Dreiser Weiher; Jfw = Jungferweiher; HlM = Hoherlist Maar; EiM = Eigelbach Maar; EEVF = East Eifel Volcanic Field; B-M = Baraque Michel; Eu = Eupen; Lg = Liège; Ma = Malmedy; Mo = Monjoie; Re = Remouchamps; St = Stavelot; StV = Saint-Vith; Ve = Verviers.

Table 1: For the Rocourt Tephra, articles reporting the presence of the RT in deposits at the sites shown in Fig. 1.

|

Authors |

Year |

Site # |

Host sediment |

|

|

n/a |

Alluvial plain |

|||

|

1 |

Soil |

|||

|

2 |

Loess section |

|||

|

|

|

3 & 4 |

Slope deposits |

|

|

|

|

5 |

Slope deposits & terrace |

|

|

1 |

Soil |

|||

|

6 |

Slope deposits |

|||

|

7 |

Valley bottom: periglacial deposits |

|||

|

8 |

Loess section |

|||

|

9 |

Terrace |

|||

|

10 |

Loess section |

|||

|

|

|

11 |

Terrace |

|

|

12 |

Loes section |

|||

|

13 |

Terrace |

|||

|

14 |

Cave deposits |

|||

|

15 |

Rampart of lithalsa |

|||

|

7 |

Valley bottom: periglacial deposits |

|||

|

2 |

Loess section |

|||

|

|

|

12 |

Loess section |

|

|

|

|

10 |

Loess section |

|

|

|

|

16 |

Loess section |

|

|

|

|

16 |

Loess section |

|

|

|

|

16 |

Short term excavation |

|

|

|

|

17 |

Short term excavation |

|

|

n/a |

Varia |

|||

|

18 |

Loess & eolian sand |

|||

|

19 |

Valley bottom: periglacial deposits |

|||

|

20 |

Loess section |

|||

|

s.o. |

Terrace |

|||

|

15 |

Slope deposits |

|||

|

21 |

Cave deposits |

|||

|

22 |

Loess section |

|||

|

15 |

Rampart of lithalsa |

|||

|

23 |

Cave deposits |

|||

|

n/a |

Loess section |

|||

|

24 |

Valley bottom: periglacial deposits |

|||

|

25 |

Loess section |

|||

|

|

|

26 |

Loess section |

|

|

25 |

Loess section |

|||

|

n/a |

Palaeolake |

|||

|

27 |

Terrace |

|||

|

n/a |

Varia |

|||

|

27 |

Loess section |

|||

|

28 |

Cave deposits |

|||

|

n/a |

Varia |

|||

|

12 |

Loess section |

|||

|

29 & 30 |

Loess section |

|||

|

12 |

Loess section |

|||

|

n/a |

Loess section |

|||

|

28 |

Cave deposits |

|||

|

12 & 25 |

Loess section |

|||

|

28 |

Cave deposits |

|||

|

31 |

Loess section |

|||

|

2, 12, 32 |

Loess section |

|||

|

|

|

28 |

Cave deposits |

|

|

|

|

27 |

Terrace |

|

|

33 |

Valley bottom: periglacial deposits |

|||

|

10 |

Loess section |

|||

|

28 |

Cave deposits |

|||

|

32 |

Loess section |

|||

|

34 |

Rampart of lithalsa |

|||

|

2 |

Loess section |

|||

|

16 |

Loess section |

|||

|

35 |

Valley bottom: periglacial deposits |

|||

2In all cases, its identification is based on the volcanic mafic mineral (vmm) assemblage as determined using a polarizing microscope, and more particularly by a high frequency of enstatite and brown amphibole. It became the Tuf de Rocourt (Juvigné, 1977b) then the Rocourt Tephra (Juvigné, 1991). The optical determination of the enstatite was confirmed by microprobe analyses by Bustamante-Santa Cruz (1973) and that of the clinopyroxenes and the amphibole by Juvigné (1990).

3When the volcanic ash was first discovered by Gullentops (1952), its origin from the West Eifel Volcanic Field (WEVF) was suspected by the author, but, to date, the emitting volcano has never been identified. Following the identification of the RT in a loess section of the Lower Rhine Bay, Gullentops and von der Hocht (1998) pointed out that the Dreiser Weiher volcano was a possible source on the sole basis of its large size and its relative proximity in the northern part of the WEVF. This hypothesis has not received any further attention. Lenaz et al. (2010) identified a tephra containing traces of enstatite in the Jungferweiher lake core (WEVF), and they clearly correlated it with the RT. Förster et al. (2020) took up the above correlation by integrating a tephra also containing traces of enstatite in two other lacustrine sequences of the WEVF, namely Eigelbach and Hoherlist maare. By designating the Pulvermaar as the source volcano for the RT occurrences in these three maare (Jungferweiher, Eigelbach, Hoherlist), the authors provoked a comparative study of the RT with the proximal tephra of Pulvermaar (Juvigné et al., 2024) This study also included the Dreiser Weiher. Juvigné et al. (2024) demonstrated by the study of the chemical composition of the pyroxenes that neither the Pulvermaar nor the Dreiser Weiher could be the source of the RT. In their paper, the optical determinations of the vmm had little weight because of the variations inherent in the complexity of the factors that can modify, at least quantitatively, the mineralogical association of the same tephra. Those factors can include the heterogeneity of the magma chamber, the alteration in the host terrains, as well as air transport and laboratory practices. Nevertheless, the results obtained by Juvigné et al. (2024) support the conclusion obtained from the chemical composition of the pyroxenes. Furthermore, in tephra correlation research, the age of a deposit constitutes a valued guide, and it has been used by Lenaz et al. (2010) and Förster et al. (2020) for the RT. However, the RT has never been found in a primary position. Despite the progress of loess stratigraphy in Belgium (Haesaerts et al., 2016), the vertical distribution of its vmm in the Lower Weichselian loess sequences weakens the narrowness of the estimate currently proposed between 78 and 80 ka. Detailed data on this subject will be provided below to illustrate this reservation.

2. Analytical Procedure

4Dense minerals (δ > 2.8) were separated as follows: boiling in HCl10%vol; sieving by 355/75 µm; extraction of dense minerals with bromoform (δ = 2.8) in a separating funnel by repeating agitation–decantation–harvest cycles, until no more harvest was obtained (generally three to five cycles). Aliquots were examined under the binocular magnifier, and smear slides were prepared in Canada balsam for identification with a petrological microscope.

3. Volcanogenic Mafic Minerals of the Rocourt Tephra

5The association consists of orthopyroxenes, clinopyroxenes, brown amphiboles, titaniferous magnetite and Cr-spinel. Due to several factors including the zonation of magma and the fallout (natural factors), as well as from sampling to optical determination (technical factors), the frequency ranges of the individual minerals are somewhat large. In the sites with high frequencies of vmm, a characteristic mineral suite was calculated (Table 2 ).

6Table 2: Percentage ranges of the vmm of the Rocourt Tephra. Explanation: Cpx = clinopyroxene; Ens = enstatite; Amp = amphibole; n = the number of grains counted; n.a. = not available.

|

Locality |

Determinator |

Ref. |

Cpx |

Ens |

Amp |

Spinel |

n |

|

Eupen, Soor valley, |

Juvigné |

[1] |

53 |

27 |

20 |

|

n.a. |

|

Eupen, Soor valley, |

Juvigné |

[2] |

50 |

25 |

25 |

|

n.a. |

|

Rocourt, loess section |

Juvigné |

[3] |

58.7 |

9.4 |

31.8 |

|

388 |

|

Kesselt, loess section |

Juvigné |

[3] |

65.5 |

13.4 |

21.1 |

|

739 |

|

Tongrinne, loess section |

Juvigné |

[3] |

49.7 |

25.6 |

24.6 |

|

107 |

|

Wanlin, loess section |

Juvigné |

[4] |

28.9 |

43.1 |

28 |

|

2888 |

|

Liernu, loess section |

Juvigné |

[5] |

22.9 |

34.9 |

42.9 |

|

73 |

|

Hautes Fagnes, |

Juvigné |

[5] |

46.8 |

22 |

31.2 |

|

n.a. |

|

Vroenhoven, loess section |

Meijs |

[6] |

76.7 |

8.7 |

13.8 |

0.8 |

n.a. |

|

Hautes Fagnes, |

Juvigné |

[7] |

45.3 |

25.5 |

29.1 |

|

1300 |

|

Trooz, Walou, cave |

Pirson & Juvigné |

[8] |

45.4 |

40.1 |

14.3 |

|

1279 |

|

Bassenge, Romont, |

Juvigné |

[9] |

90.9 |

3.8 |

5.2 |

|

10550 |

|

Remicourt, loess section |

Juvigné |

[10] |

67.2 |

10 |

22.7 |

|

3735 |

|

Min. |

|

|

22.9 |

3.8 |

5.2 |

|

|

|

Max. |

|

|

90.9 |

43.1 |

42.9 |

|

|

|

References: [1] – Bastin et al. (1972); [2] – Pissart et al. (1975); [3] – Juvigné (1976); [4] – Juvigné (1979a); [5] – Bolline et al. (1980); [6] – Meijs and de Lang (1983); [7] – Juvigné (1985); [8] – Pirson and Juvigné (2011); [9] – Juvigné et al. (2008); [10] – Juvigné et al. (2013). |

|||||||

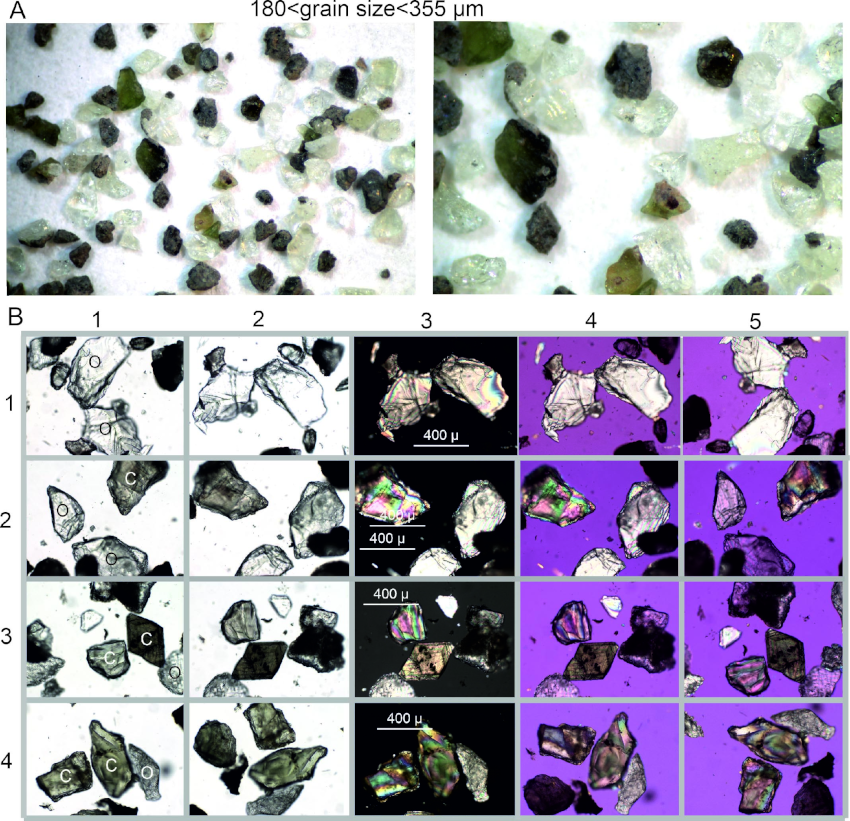

7Photographs of the three most common volcanogenic mafic minerals of the Rocourt Tephra are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Photographs of the three most common volcanogenic mafic minerals of the Rocourt Tephra. Rows: E = enstatite; A = amphibole; C = clinopyroxene. Columns: (1) and (2) orthogonal positions in plane-polarized light to highlight pleochroism; (3), (4), (5) maximum illumination between cross-polarized light to highlight birefringence with intercalated gypsum (4) and (5).

4. The Dreiser Weiher Tephra

8The location of the volcano and the detailed positions of the samples stratigraphically are available in Juvigné et al. (2024, Fig. 3). Two populations share some 90% of the entire population: very dark green to black euhedral minerals coated with dark magmatic glass and colorless to greenish grains which are not coated with magmatic glass. The magmatic coating impairs the transparency during microscope examination. Nevertheless, numerous dark green euhedral minerals could be identified as clinopyroxene as well as agglomerates of small euhedral clinopyroxenes. The colorless crystals consist of olivine. Traces of another two minerals were found: anhedral lawn-green crystals with serrated edges (clinopyroxene) and prismatic brown minerals (amphiboles). No significant stratigraphic variation was observed in the sequence (Table 3). Photographs of the three most common volcanogenic mafic minerals of the Dreiser Weiher Tephra are presented in Figure 3.

Table 3: Frequency (%) of the volcanogenic mafic mineral suite of the Dreiser Weiher Tephra after optical determinations (magnifier and microscope). Explanation: n = number of mineral grains counted.

|

Label |

Clinopyroxene |

Enstatite +amphibole |

Olivine |

n |

|

Dreiser Weiher 2 |

38.5 |

0 |

61.5 |

117 |

|

Dreiser Weiher 3 |

40.0 |

2.9 |

57.1 |

105 |

|

Dreiser Weiher 4 |

46.7 |

0 |

53.3 |

112 |

Figure 3: Photographs of the two most common volcanogenic mafic minerals of the Dreiser Weiher Tephra. C = cpx; O = olivine.

(A) Under magnifier: dark grains are clinopyroxenes; colorless to pale greenish grains are olivines.

(B) Rows: C = clinopyroxene; O = olivine. Columns: (1) and (2) orthogonal positions in plane-polarized light to highlight pleochroism; (3), (4), (5) maximum illumination between cross-polarized light to highlight birefringence with intercalated gypsum in (4) and (5).

5. The Pulvermaar Tephra

9The location of the volcano and the detailed position of the samples are given in Juvigné et al. (2024, Fig. 4).

10Two populations make up most of the mass: very dark green to black grains mainly coated with magmatic glass are largely dominant over transparent colorless grains. Under the microscope, magmatic glass coating impairs the transparency of the former minerals. Nevertheless, several of them could be identified as subhedral to euhedral clinopyroxene as well as agglomerates of small euhedral clinopyroxenes. The transparent colorless minerals are likely to be olivine. Otherwise, a few anhedral lawn-green minerals with serrated edges are present (clinopyroxene) as well as traces of prismatic brown grains (amphibole). The latter two minerals and the olivines are not coated with magmatic glass and so are grains of coarser crystals. Qualitative examination of the eighteen samples has been done and no significant stratigraphical variation was observed (Table 4 ).

Table 4: Frequency (%) of the volcanogenic mafic mineral suite of the Pulvermaar Tephra after optical determinations (magnifier and microscope). Explanation: n = number of mineral grains counted.

|

Label |

Clinopyroxene |

Enstatite + amphibole |

Olivine |

n |

|

Pulvermaar 1 |

88.7 |

0 |

11.3 |

106 |

|

Pulvermaar 2 |

76.1 |

2.2 |

21.7 |

105 |

|

Pulvermaar 3 |

92.7 |

0 |

7.3 |

123 |

|

Pulvermaar 4 |

95.3 |

0 |

4.7 |

128 |

|

Pulvermaar 5 |

96.2 |

1.9 |

1.9 |

106 |

|

Pulvermaar 6 |

97.1 |

0 |

2.9 |

134 |

|

Pulvermaar 7 |

98.3 |

0 |

1.7 |

116 |

|

Pulvermaar 8 |

93.4 |

1.6 |

4.9 |

122 |

|

Pulvermaar 9 |

91.8 |

2 |

6.1 |

105 |

|

Pulvermaar 10 |

88.4 |

11.6 |

0 |

109 |

|

Pulvermaar 11 |

81.8 |

18.2 |

0 |

110 |

|

Pulvermaar 12 |

94.8 |

5.2 |

0 |

144 |

|

Pulvermaar 13 |

88.6 |

8.5 |

2.9 |

105 |

|

Pulvermaar 14 |

87.5 |

12.5 |

0 |

112 |

|

Pulvermaar 15 |

96.8 |

13.2 |

0 |

126 |

|

Pulvermaar 16 |

94.9 |

5.1 |

0 |

118 |

|

Pulvermaar 17 |

89.6 |

10.4 |

0 |

134 |

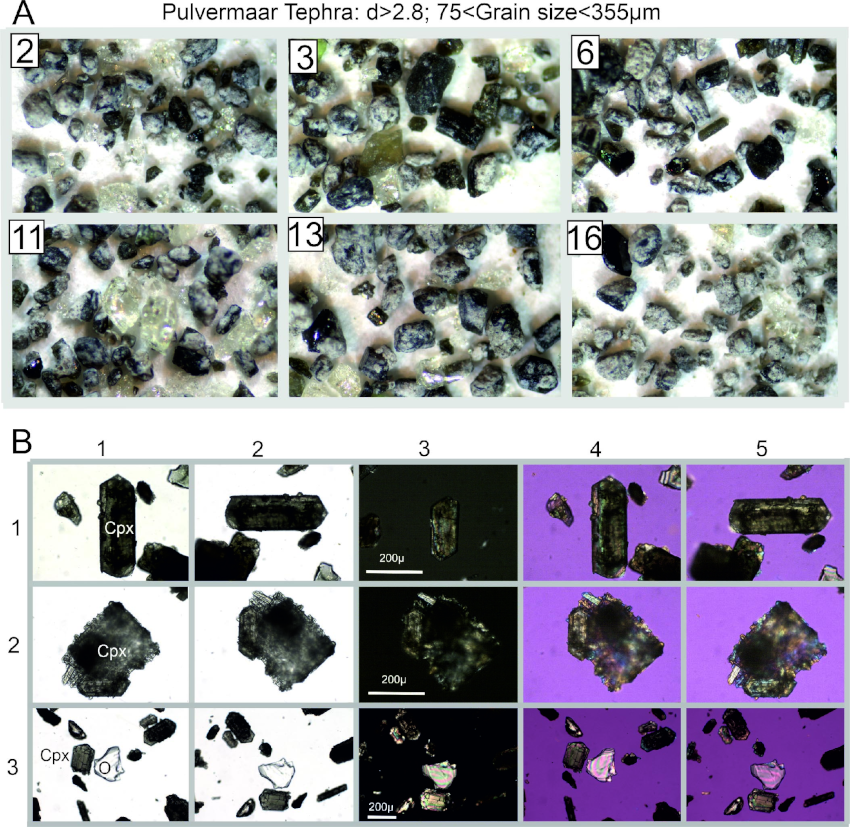

11Photographs of the two most common volcanogenic mafic minerals of the Pulvermaar Tephra are presented in Fig. 4

Figure 4: Photographs of the two most common volcanogenic mafic minerals of the Pulvermaar Tephra. (A) Under magnifier: dark grains are clinopyroxenes; colorless to pale greenish grains are olivines. (B) Rows: (1) Cpx = euhedral clinopyroxene (single mineral or agglomerate); O = olivine. Columns: (1) and (2) orthogonal positions in plane polarized light to highlight pleochroism; (3), (4), (5) maximum illumination between cross polarized light to highlight birefringence with intercalated gypsum in (4) and (5).

6. Stratigraphical Distribution of the Rocourt Tephra

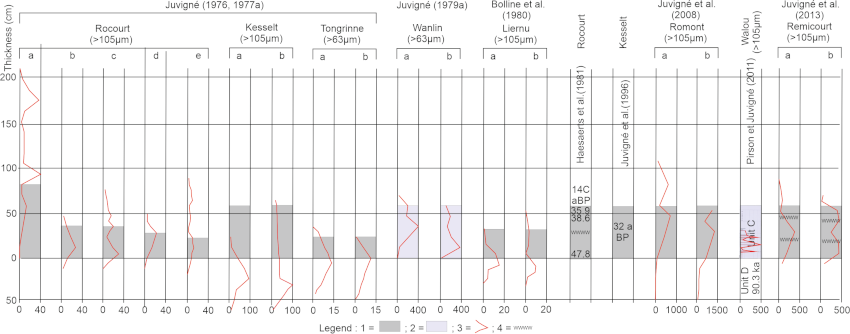

12In sites where the Upper Pleistocene lithostratigraphic units are sufficiently developed, the vertical distribution of the vmm was investigated, with the aim of finding the RT layer visible to the naked eye at a peak of concentration. However, the objective of identifying the RT in its primary position has never been achieved. In some cases, secondary concentration peaks have been highlighted (Fig. 5). The part above the main peak comes from sedimentary reworking and the lower part from bioturbation (Juvigné, 1977b).

Figure 5: Vertical distribution of vmm of the RT in Upper Pleistocene sequences in Belgium. Legend: 1 = Humiferous Complex of Remicourt (HCR); 2 = palaeosol; 3 = frequency of vmm of the RT; 4 = unconformity. Horizontal scale = quantity of vmm for varying weights of sediment from one site to another (see the original publications).

13In the loess region of Middle Belgium (Rocourt, Kesselt, Romont, Veldwezelt, Remicourt, Tongrinne – Fig. 5), the tephra is systematically associated with a humiferous pedocomplex known as the Humiferous Complex of Remicourt (HCR; Haesaerts et al., 1997, 2016). In High Belgium, two sites yielded detailed data for the RT stratigraphic distribution. In the Walou Cave, the distribution peak is located on top of a humiferous horizon (unit CV-1), overlying a complex sequence including palaeosols (units DI-BT, CV-3 and CV-2; Pirson and Juvigné, 2011). In the Wanlin brickyard, the peak of the RT was observed at the boundary between two palaeosols separated by a stony layer (Juvigné, 1979a).

14Hence, it seems that the fallout of the RT has occurred during a period of (relatively strong) soil formation, with sufficiently intense biological activity to disseminate the RT into the underlying units. In all the cases, the peak is situated above the Rocourt Pedocomplex or its equivalent. In the most complete loessic sequences, the vmm concentration peak is generally in the Humiferous Complex of Remicourt (see Juvigné et al., 2013; Haesaerts et al., 2016) There are a few exceptions, however. In one of the sequences studied at Rocourt, the RT peak was found above the HCR, but in other sequences, it was observed inside the HCR. In two sequences from Kesselt, the peak is below the HCR, but on other sequences from the same site, the highest concentration of RT-vmm was found inside the HCR. At Tongrinne, the peak is located at the contact between the Rocourt Pedocomplex and the overlying HCR.

15Regarding the age of the RT, according to Haesaerts et al. (2016), the Rocourt Pedocomplex is attributed to the Eemian interglacial and to the main part of the Weichselian Early Glacial (GS 25 to the lower half of GI 21, sensu Rasmussen et al., 2014). Therefore, again according to Haesaerts et al. (2016), the overlying Humiferous Complex of Remicourt bearing the RT is attributed to the end of GI 21 (ca. 78–80 ka; Juvigné et al., 2013). It is worth mentioning here that following Antoine et al. (2016), the equivalent of HCR is correlated with GI 20 and GI 19. Based on this viewpoint, the age of the RT would be slightly younger, 76.5–70 ka, following the Rasmussen et al. (2014) chronology. We therefore suggest here to consider the range 80–70 ka for the age of the fallout in order to widen the scope for determining the ages of volcanoes or tephras in the Eifel Volcanic Field.

7. About Correlations with the Rocourt Tephra

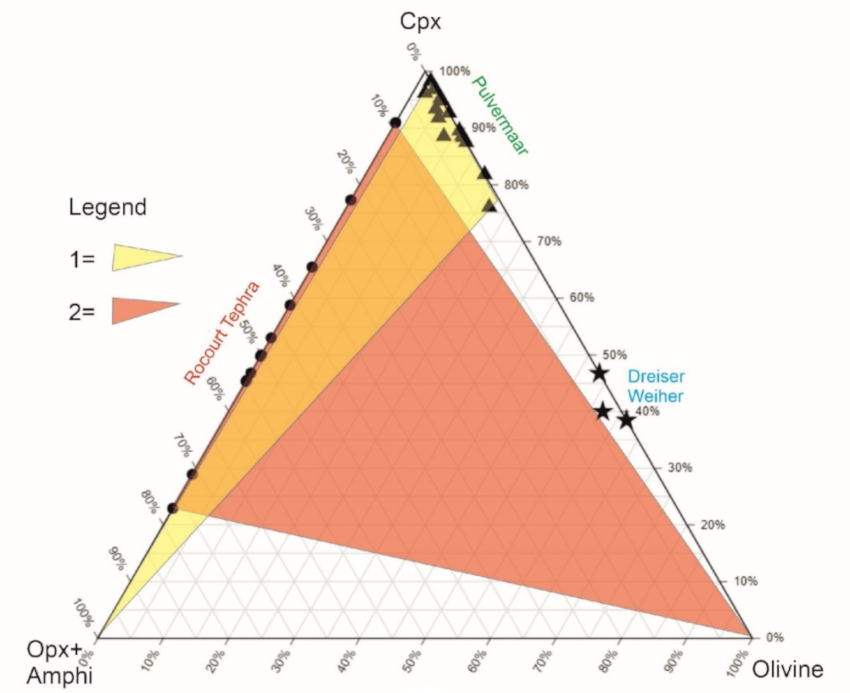

16The identification of RT in some 35 sites in Belgium and in the neighboring regions of the Netherlands and the Lower Bay Rhine was based solely on determinations of vmm made under the microscope, and more particularly on the presence of enstatite as a marker mineral. The correlation of RT with products of the Dreiser Weiher (Gullentops and von der Hocht, 1998) or of the Pulvermaar (Förster et al., 2020) was rejected mainly by the geochemical fingerprints of pyroxenes (Juvigné et al., 2024). The detailed optical mineralogy data added in this paper allows us to argue in the same way. The photographs show fragments of megacrysts (without glass coatings) in the RT and euhedral clinopyroxenes with glass coating at Pulvermaar. Moreover, in a ternary diagram, there is no overlapping of the fields of the mineralogical associations of the three tephras (Fig. 6 ). It is also difficult to accept that weathering could have caused the disappearance of the amphiboles and enstatites from the Pulvermaar T. and the Dreiser Weiher T. and/or the olivines from the RT. Even if their total alteration were accepted, one could not obtain overlapping of the respective fields.

Figure 6: Comparisons of vmm associations of RT (black circles), Pulvermaar (black triangles) and Dreiser Weiher (black stars). Legend: 1 = possible distribution of the vmm association assuming the disappearance by alteration of brown amphiboles and enstatites in the proximal tephra of the Pulvermaar T.; 2 = possible distribution of the vmm association of the RT assuming the disappearance by alteration of olivines in all types of host sediments.

8. About the Presence of the RT at Schwalbenberg

17Fischer et al. (2021) report the presumed presence of the RT in the Schwalbenberg loess section (Middle Rhine valley). It is a centimeter-thick, coarse-grained tephra resting on a paleosol which could be the equivalent of the HCR in Belgium (see above). Unfortunately, the authors do not report any mineralogical or geochemical data concerning the RT in the Schwalbenberg loess. Their hypothesis calls for further investigations, because: (1) the site is on the road to the Inden and Garzweiler mines (Lower Bay Rhine) where Gullentops and von der Hocht (1998) found the RT; (2) the source volcano could be in the nearby East Eifel Volcanic Field, an unexpected hypothesis.

9. Conclusion

18Thus far, the volcano that has erupted the RT has not yet been identified. However, both the Pulvermaar and the Dreiser Weiher volcanoes can be ruled out, even though they have been suggested (erroneously) as sources in the literature. To propose the correlation of tephras with the RT, it is essential to refer not only to the chemical composition of the pyroxenes, but also to the association of volcanic mafic minerals which is characterised by high frequencies of megacrystal fragments of enstatite and brown amphibole in the absence of olivine. The earlier age estimate for the RT of 78 to 80 ka (Juvigné et al., 2024)) is dependent on the stratigraphy of the loess compared to the INTIMATE curve, because the original stratigraphical position of the tephra is unknown. However, another stratigraphic-based suggestion for the age of RT is from 76.5 to 70 ka. Therefore, evidence of the presence of RT should not be sought only in the narrow age range of 78 to 80 ka but in the range 80-70 ka.

Acknowledgments

19We warmly thank Dr. Andreas Schüller, coordinator of scientific research in UNESCO Natur- und Geopark Vulkaneifel, who agreed that we could take samples from the old quarry opening in the rampart of the Pulvermaar. David J. Lowe (emeritus professor, University of Waikato) is warmly thanked for improving the text and revising the English. Constructive review and comment by Pierre Antoine also improved the manuscript and are greatly appreciated.

Further Information

Author contributions

20Etienne Juvigné: conceptualization, formal analysis, methodology, project administration, original draft writing, writing revision; André Pouclet, Jacques-Marie Bardintzeff, Stéphane Pirson: formal analysis, methodology, original draft writing, writing revision.

Conflicts of interest

21The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Bibliographie

Antoine, P., Coutard, S., Guerin, G., Deschodt, L., Goval, E., Locht, J.-L., and Paris, C. (2016) Upper Pleistocene loess–palaeosol records from Northern France in the European context: Environmental background and dating of the Middle Palaeolithic. Quaternary International, 411, 4–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2015.11.036.

Ballmann, P., De Coninck, J., de Heinzelin, J., Gautier, A., Geets, S., and Rage, J.-C. (1980) I. – Les dépôts quaternaires; inventaire paléontologique et archéologique. In La caverne Marie-Jeanne (Hastière-Lavaux, Belgique), edited by Gautier, J. A. and de Heinzelin, J., Mémoires de l’Institut royal des Sciences naturelles de Belgique, volume 177, pages 5–24. https://biblio.naturalsciences.be/rbins-publications/memoirs-of-the-royal-belgian-institute-of-natural-sciences-first-series/177-1980/vol-177-013cd0p-text-5-24.pdf.

Bastin, B. and Juvigné, E. (1978) L’âge des dépôts de la vallée morte des Chôdires (Malmedy). Annales de la Société géologique de Belgique, 101, 289–304. https://popups.uliege.be/0037-9395/index.php?id=4509.

Bastin, B., Juvigné, E., Pissart, A., and Thorez, J. (1972) La vallée de la Soor (Hautes Fagnes): compétence actuelle de la rivière: dépôts glaciaires ou périglaciaires. In Processus périglaciaires étudiés sur le terrain. Compte rendu de l’excursion du 3 juillet 1971, Les Congrès et Colloques de l’Université de Liège, volume 67, pages 295–321. Université de Liège.

Bastin, B., Juvigné, E., Pissart, A., and Thorez, J. (1974) Etude d’une coupe dégagée à travers un rempart d’une cicatrice de pingo de la Brackvenn. Annales de la Société géologique de Belgique, 97(2), 341–358. https://popups.uliege.be/0037-9395/index.php?id=5624.

Bolline, A., Pissart, A., Bastin, B., and Juvigné, E. (1980) Etude d’une dépression fermée près de Gembloux : vitesse de l’érosion des terres cultivées de Hesbaye. Annales de la Société géologique de Belgique, 103, 143–152. https://popups.uliege.be/0037-9395/index.php?id=4058.

Bourguignon, P. (1955) Minéraux volcaniques dans les limons gaumais. Annales de la Société géologique de Belgique, 78, 173–177.

Bringmans, P. M. M. A., Vermeersch, P. M., Gullentops, F., Groenendijk, A. J., Meijs, E. P. M., de Warrimont, J.-P., and Cordy, J.-M. (1999-2000) Preliminary excavation report on the Middle Palaeolithic valley settlements at Veldwezelt–Hezerwater (prov. of Limburg). Archeologie in Vlaanderen, VII, 9–30. https://doi.org/10.55465/DLVI6135.

Bustamante-Santa Cruz, L. (1973) Les minéraux lourds des alluvions sableuses du bassin de la Meuse. Ph.D. thesis, Katholieke Universiteit te Leuven, Leuven (BE).

Bustamante Santa Cruz, L. (1974) Les minéraux lourds des alluvions du bassin de la Meuse. Comptes rendus de l’Académie des Sciences de Paris, Série D, 278(Partie 1), 561–564. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k5810128m/f685.item.

Ek, C. (1974) Etude sédimentologique dans la grotte de Remouchamps. Bulletin de la Société royale Belge d’Anthropologie et de Préhistoire, 85, 16–41. https://biblio.naturalsciences.be/associated_publications/anthropologica-prehistorica/bulletin-de-la-societe-royale-belge-d-anthropologie-et-de-prehistoire/ap-085-1974/ap85_p16-41.pdf.

Fischer, P., Jöris, O., Fitzsimmons, K. E., Vinnepand, M., Prud’homme, C., Schulte, P., Hatté, C., Hambach, U., Lindauer, S., Zeeden, C., Peric, Z., Lehmkuhl, F., Wunderlich, T., Wilken, D., Schirmer, W., and Vött, A. (2021) Millennial-scale terrestrial ecosystem responses to Upper Pleistocene climatic changes: 4D-reconstruction of the Schwalbenberg Loess–Palaeosol–Sequence (Middle Rhine Valley, Germany). CATENA, 196, 104913. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2020.104913.

Förster, M. W., Zemlitskaya, A., Otter, L. M., Buhre, S., and Sirocko, F. (2020) Late Pleistocene Eifel eruptions: insights from clinopyroxene and glass geochemistry of tephra layers from Eifel Laminated Sediment Archive sediment cores. Journal of Quaternary Science, 35(1-2), 186–198. https://doi.org/10.1002/jqs.3134.

Gullentops, F. (1952) Découverte en Ardenne de minéraux d’origine volcanique de l’Eifel. Bulletins de l’Académie Royale de Belgique, 38(1), 736–740. https://doi.org/10.3406/barb.1952.69692.

Gullentops, F. (1954) Contributions à la chronologie du Pléistocène et des formes du relief en Belgique. Mémoires de l’Institut géologique de l’Université de Louvain, 18, 125–252.

Gullentops, F. and von der Hocht, F. (1998) Der Enstatit-Tuff am Niederrhein. In DEUQUA-Jubiläums-Hauptversammlung in Hannover, 13–20. September 1998, edited by Feldmann, L., Benda, L., and Look, E.-R., page 70. Hannover (DE).

Haesaerts, P., Damblon, F., Gerasimenko, N., Spagna, P., and Pirson, S. (2016) The Late Pleistocene loess-palaeosol sequence of Middle Belgium. Quaternary International, 411(Part A), 25–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2016.02.012.

Haesaerts, P., Juvigné, E., Kuyl, O., Mucher, H., and Roebroeks, W. (1981) Compte rendu de l’excursion du 13 juin 1981, en Hesbaye et au Limbourg néerlandais, consacrée à la chronostratigraphie des loess du Pléistocène supérieur. Annales de la Société géologique de Belgique, 104(2), 223–240. https://popups.uliege.be/0037-9395/index.php?id=4135.

Haesaerts, P., Mestdagh, H., and Bosquet, D. (1997) La séquence lœssique de Remicourt (Hesbaye, Belgique). Notae Praehistoricae, 17, 45–52. https://biblio.naturalsciences.be/associated_publications/notae-praehistoricae/NP17/np17_45-52.pdf.

Hermans, W. F. (1955) Description et genèse des dépôts meubles de surface et du relief de l’Oesling (Ardennes Luxembourgeoises), Publications du Service Géologique de Luxembourg, volume XI. Service géologique de Luxembourg, 94 pages. https://geologie.lu/index.php/telechargements/download/6-publications-sgl-volumes/497-v11.

Jouannic, G., Walter-Simonnet, A. V., Bossuet, G., Simonnet, J. P., and Jacotot, A. (2016) Evidence of tephra reworking in loess based on 2D magnetic susceptibility mapping: A case study from Rocourt, Belgium. Quaternary International, 394, 123–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2015.10.098.

Juvigné, E. (1973) Datation de sédiments quaternaires à Tongrinne et à Tilff par des minéraux volcaniques. Annales de la Société géologique de Belgique, 96(2), 411–412. https://popups.uliege.be/0037-9395/index.php?id=5883.

Juvigné, E. (1974) Découverte de minéraux volcaniques à Kesselt (Limbourg). Annales de la Société géologique de Belgique, 97(1), 287–288. https://popups.uliege.be/0037-9395/index.php?id=5590.

Juvigné, É. (1976) Contribution à la connaissance de la stratigraphie du Quaternaire par l’étude des minéraux denses transparents de l’Eifel au Massif Central français et plus particulièrement en Belgique. Ph.D. thesis, Université de Liège, Laboratoire de Géographie physique, Liège BE.

Juvigné, E. (1977a) Déflation éolienne sur les alluvions de l’Ourthe au Pléistocène. Revue belge de Géographie, 101, 175–185.

Juvigné, E. (1977b) Zone de dispersion et âge des poussières volcaniques du tuf de Rocourt. Annales de la Société géologique de Belgique, 100, 13–22. https://popups.uliege.be/0037-9395/index.php?id=4564.

Juvigné, E. (1979a) Etude stratigraphique des dépôts du méandre recoupé de la Lesse à Wanlin (Famenne). Bulletin de la Société géographique de Liège, 15, 65–75. https://popups.uliege.be/0770-7576/index.php?id=5148.

Juvigné, E. (1979b) L’encaissement des rivières ardennaises depuis le début de la dernière glaciation. Zeitschrift für Geomorphologie, 23, 291–300.

Juvigné, E. (1985) Données nouvelles sur l’âge de la capture de la Warche à Bévercé. Bulletin de la Société géographique de Liège, 21, 3–11. https://popups.uliege.be/0770-7576/index.php?id=5322.

Juvigné, E. (1990) About some widespread Late Pleistocene tephra horizons in Middle Europe. Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie – Monatshefte, 1990(4), 215–232. https://doi.org/10.1127/njgpm/1990/1990/215.

Juvigné, E. (1991) La téphrostratigraphie et sa nomenclature de base en langue fran caise : mises au point et suggestions. Annales de la Société géologique de Belgique, 113(2), 295–298. https://popups.uliege.be/0037-9395/index.php?id=1305.

Juvigné, E. (1993) Contribution à la téphrostratigraphie du Quaternaire et son application à la géomorphologie, Mémoires pour servir à l’Explication des Cartes Géologiques et Minières de la Belgique, volume 36. Geological Survey of Belgium, Brussels (BE), 66 pages. http://biblio.naturalsciences.be/rbins-publications/memoirs-of-the-geological-survey-of-belgium/pdfs/msgb-1993-36x.pdf.

Juvigné, E. (2016) Le vivier de référence de la Konnerzvenn, restauration du site. Hautes Fagnes, 2016(4), 25–27.

Juvigné, E., Haesaerts, P., Mestdagh, H., Pissart, A., and Balescu, S. (1996) Révision du stratotype loessique de Kesselt (Limbourg, Belgique). Comptes Rendus de l’Académie des Sciences de Paris, série IIa, 323(9), 801–807. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k6200604d?rk=450646;0.

Juvigné, E., Marion, J.-M., and Houbrechts, G. (2022) La Statte inférieure: reconnaissance pionnière de l’évolution de la vallée. Hautes Fagnes, 2022(1), 22–27. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/377530313.

Juvigné, E. and Mörner, N.-A. (1984) A volcanic ash-fall at the Early/Mid Weichselian-Würmian transition in the bog of the Grande Pile (Vosges, France). Eiszeitalter u. Gegenwart, 34(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.3285/eg.34.1.01.

Juvigné, E. and Mullenders, W. (1972) Compte rendu de l’excursion du 4 juillet 1971 en Famenne et à Treignes. In Processus périglaciaires étudiés sur le terrain, Les Congrès et Colloques de l’Université de Liège, volume 67, pages 323–333.

Juvigné, E. and Pissart, A. (1979) Un sondage sur le plateau des Hautes Fagnes au lieu-dit « La Brackvenn ». Annales de la Société géologique de Belgique, 102, 277–284. https://popups.uliege.be/0037-9395/index.php?id=4344.

Juvigné, E., Pouclet, A., Haesaerts, P., Bosquet, D., and Pirson, S. (2013) Le Téphra de Rocourt dans le site paléolithique moyen de Remicourt (province de Liège, Belgique) [The Rocourt Tephra in the middle paleolithic site of Remicourt (province of Liège, Belgium)]. Quaternaire, 24(3), 279–291. https://doi.org/10.4000/quaternaire.6738.

Juvigné, E., Pouclet, A., Pirson, S., and Bardintzeff, J.-M. (2024) Reappraisal of the volcanic source of the Rocourt Tephra, a widespread chronostratigraphic marker aged ca. 78–80 ka in Western Europe. Bulletin of Volcanology, 86(7), 66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00445-024-01756-2.

Juvigné, E., Tallier, E., Haesaerts, P., and Pirson, S. (2008) Un nouveau stratotype du téphra de Rocourt dans la carrière de Romont (Eben/ Bassenge, Belgique) [A new stratotype of the Rocourt tephra in the Romont quarry (Eben/ Bassenge, Belgium)]. Quaternaire, 19(2), 133–139. https://doi.org/10.4000/quaternaire.2742.

Lacroix, D. (1993) Les minéraux denses transparents des dépôts de la grotte Walou à Trooz (Province de Liège, Belgique). In Recherches à La Grotte Walou à Trooz (Province de Liège, Belgique) : Premier Rapport de Fouille, edited by Dewez, M., Collcutt, S. N., Cordy, J.-M., Gilot, E., Groessens-Van Dyck, M.-Cl., Heim, J., Kozlowski, S., Sachse-Kozlowska, E., Lacroix, D., and Simonet, P., number 7 in Mémoires, pages 25–31. Société Wallonne de Palethnologie.

Lenaz, D., Marciano, R., Veres, D., Dietrich, S., and Sirocko, F. (2010) Mineralogy of the Dehner and Jungferweiher maar tephras (Eifel, Germany). Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie – Abhandlungen, 257(1), 55–67. https://doi.org/10.1127/0077-7749/2010/0062.

Mees, R. P. R. and Meijs, E. P. M. (1984) Note on the presence of Pre-Weichselian Loess deposits along the Albert Canal near Kesselt and Vroenhoven (Belgian Limbourg). Geologie en Mijnbouw, 63(1), 7–11. https://drive.google.com/open?id=0B7j8bPm9Cse0Q3RWbllUZGlNam8.

Meijs, E. P. M. (2002) Loess stratigraphy in Dutch and Belgian Limburg. Eiszeitalter und Gegenwart, 51, 115–131. https://doi.org/10.3285/eg.51.1.08.

Meijs, E. P. M. (2011) The Veldwezelt site (province of Limburg, Belgium): environmental and stratigraphical interpretations. Netherlands Journal of Geosciences – Geologie en Mijnbouw, 90(2-3), 73–94. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0016774600001037.

Meijs, E. P. M. and de Lang, F. D. (1983) Eerste aanzet tot een nadere stratigrafische onderverdeling van de Nuenen Groep op grond van sonderingen en mineralisch onderzoek. Technical Report OP 5613, Rijks Geologische Dienst„ Afdeling Kartering, Distrikt Zuid, Haarlem (NL).

Meijs, E. P. M. and Groenendijk, A. J. (1999) Midden-Paleolithische vondst in een nieuwe geologische context. Archeologie in Limburg, 79, 1–5.

Pirson, S., Drailly, C., Court-Picon, M., Damblon, F., and Haesaerts, P. (2004) La nouvelle séquence stratigraphique de la grotte Walou (Belgique). Notae Praehistoricae, 24, 31–45. https://biblio.naturalsciences.be/associated_publications/notae-praehistoricae/NP24/np24_31-45.pdf.

Pirson, S. and Juvigné, E. (2011) Bilan sur l’étude des téphras à la grotte Walou. In La grotte Walou à Trooz (Belgique). Fouilles de 1996 à 2004 – Volume 1 : Les sciences de la terre, edited by Pirson, S., Draily, C., and Toussaint, M., Études et documents — Archéologie, volume 20, pages 134–167. Service public de Wallonie, Namur (BE).

Pissart, A. (1974) La Meuse en France et en Belgique : Formation du bassin hydrographique – Les terrasses et leurs enseignements. In L’évolution quaternaire des bassins fluviaux de la Mer du Nord méridionale, edited by Macar, P., Gullentops, F., Pissart, A., Tavernier, R., and Zonneveld, J. I. S., Annales de la Société géologique de Belgique Special Publica, pages 105–131. Société géologique de Belgique, Liège (BE). https://popups.uliege.be/0037-9395/index.php?id=3774.

Pissart, A., Bastin, B., Juvigné, E., and Thorez, J. (1975) Étude génétique, palynologique et minéralogique des dépôts périglaciaires de la vallée de la Soor (Hautes Fagnes, Belgique). Annales de la Société géologique de Belgique, 98(2), 415–439. https://popups.uliege.be/0037-9395/index.php?id=4982.

Pissart, A. and Juvigné, E. (1980) Genèse et âge d’une trace de butte périglaciaire (pingo ou palse) de la Konnerzvenn (Hautes Fagnes, Belgique). Annales de la Société géologique de Belgique, pages 73–86. https://popups.uliege.be/0037-9395/index.php?id=4049.

Pissart, A. and Juvigné, E. (1982) Un phénomène de capture près de Malmédy : la Warche s’écoulait autrefois par la vallée de l’Eau Rouge. Annales de la Société géologique de Belgique, 105(1), 73–86. https://popups.uliege.be/0037-9395/index.php?id=3280.

Pouclet, A. and Juvigné, E. (1993) La Téphra de Rocourt en Belgique : recherche de son origine d’après la composition des pyroxènes. Annales de la Société géologique de Belgique, 116(1), 137–145. https://popups.uliege.be/0037-9395/index.php?id=3042.

Pouclet, A., Juvigné, E., and Pirson, S. (2008) The Rocourt Tephra, a widespread 90–74 ka stratigraphic marker in Belgium. Quaternary Research, 70(1), 105–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yqres.2008.03.010.

Quinif, Y., Dupuis, C., Bastin, B., and Juvigné, E. (1979) Étude d’une coupe dans les sédiments quaternaires de la grotte de la Vilaine Source (Arbre, Belgique). Annales de la Société géologique de Belgique, 102(1), 229–241. https://popups.uliege.be/0037-9395/index.php?id=4335.

Rasmussen, S. O., Bigler, M., Blockley, S. P., Blunier, T., Buchardt, S. L., Clausen, H. B., Cvijanovic, I., Dahl-Jensen, D., Johnsen, S. J., Fischer, H., Gkinis, V., Guillevic, M., Hoek, W. Z., Lowe, J. J., Pedro, J. B., Popp, T., Seierstad, I. K., Steffensen, J. P., Svensson, A. M., Vallelonga, P., Vinther, B. M., Walker, M. J. C., Wheatley, J. J., and Winstrup, M. (2014) A stratigraphic framework for abrupt climatic changes during the Last Glacial period based on three synchronized Greenland ice-core records: refining and extending the INTIMATE event stratigraphy. Quaternary Science Reviews, 106, 14–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2014.09.007.

Renson, V., Juvigné, E., and C., D. (2002) Intérêt de la téphrostratigraphie dans le site archéologique et paléontologique du Pléistocène supérieur et de l’Holocène de la grotte Walou (Trooz, Belgique). Les dossiers de l’Archéo-Logis, 2, 23–30.

Rixhon, G. and Juvigné, E. (2010) Periglacial deposits and correlated processes in the Ninglinspo Valley (Ardenne massif, Belgium). Geologica Belgica, 13(1-2), 49–60. https://popups.uliege.be/1374-8505/index.php?id=2853.

Tavernier, R. and Laruelle, J. (1952) Bijdrage tot de petrologie van de recente afzettingen van het Ardeense Maasbekken. Natuurwetenschappelijk Tijdschrift, 34, 81–98.

Pour citer cet article

A propos de : Étienne Juvigné

ejuvigne@skynet.be

A propos de : André Pouclet

A propos de : Stéphane Pirson

Agence wallonne du Patrimoine, Direction scientifique et technique, 5100 Jambes