- Accueil

- Volume 19 : 2019

- Exploring Self-determination Referenda in Europe

- Referendums in Greenland - From Home Rule to Self-Government

Visualisation(s): 12306 (13 ULiège)

Téléchargement(s): 0 (0 ULiège)

Referendums in Greenland - From Home Rule to Self-Government

Abstract

Greenland is a case of a delegation model, where powers from the state have been delegated in a step-wise manner from time to time. The model used by Denmark and Greenland in their relationship is based on negotiations between the two governments. Usually commissions are established with an equal number of representatives from each side. This is illustrated by the two autonomy referendums, which this article focuses on. In a time of a political awakening period from the 1960s through the 1970s voices for more autonomy was on the agenda, which led to the first autonomy referendum back in 1979. After 20 years of Home Rule, while Greenland had fulfilled the Home Rule Act new negotiations were taken place in order to enhance the self-government. This led to the second autonomy referendum in 2008 with the implementation of the Self-Government Act in 2009. Greenland is now in a process towards further autonomy or even outright independence.

Table des matières

Introduction

1Greenland has developed politically and economically from a trading colony back in 1721 to 1953. In 1953, Greenland became an integral part of the Danish Kingdom due to the decolonization period. At this time the island became a county amongst other counties in Denmark. Several modernization programs started during the 1950s-1960s in order to develop the infrastructure and improve the living standards and the housing area in Greenland. These programs were influenced by Danish entrepreneurs, who were working in Greenland and the elite was still led by Danes at the time. An awakening period started in the 1960s due to Greenlanders, who had taken their higher education in Denmark and could see the island's development from an outside perspective. They became frustrated over the Danish dominance within the society and the discrimination policy that was outlined against the local population. The so-called birth criterion was one of the triggering issues, which led to protests from the educated Greenlanders. The birth criterion gave Danes better salaries and living conditions in Greenland, while the local population was given lower salaries and worse conditions in their own region, even though they performed the same work. A protest party called the Inuit Party was established in 1964. This party was nationalistic in its outlook and focused on viewing Greenlanders as a distinct people with their own culture, traditions and language. However, the party became no success and the only representative that was elected was on an added mandate in the county council in 1967 and a few years later the party ceased to exist.1

2 During the 1970s a movement called "new politics" became apparent and Greenlandic politicians were now organizing themselves into factual political parties. The first real political party was Siumut, meaning forward and was established around 1975-76. The first party program had two main dimensions: the relationship with Denmark on the one hand and the internal conditions in Greenland on the other hand. The relationship with Denmark was seen as an opportunity to develop into Home Rule within the Danish Realm. The internal conditions were seen with socialistic eyes, where fellowship, social safety and equality regarding salary were the focus points.2

3 As a counterbalance a more conservative group formed another party called Atassut, meaning solidarity in 1978. This group of politicians was more eager to keep Greenland within the Kingdom of Denmark. According to this party the best way for Greenland was to stay within the Union.3 A third political movement started to appear in the end of the 1970s. This was a more radical nationalistic and socialistic movement called Inuit Ataqatigiit, meaning Inuit community. Their goal was national self-determination and to acknowledge the people of Greenland as a distinct people.4

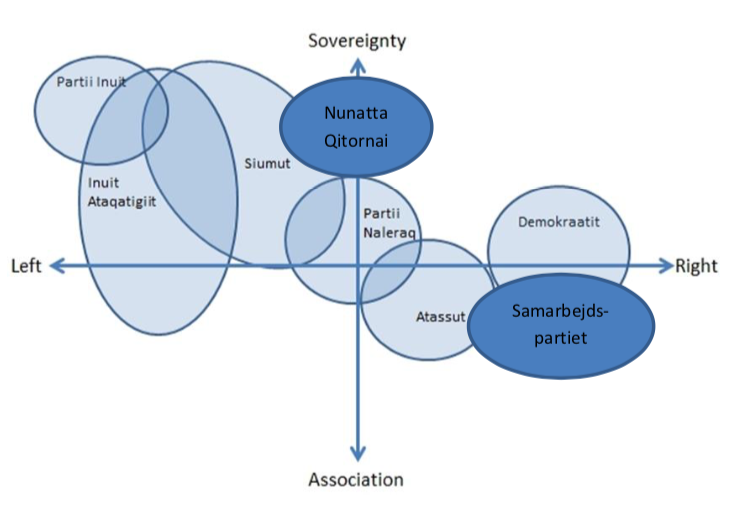

4 The three traditional parties still exist in Greenlandic politics today but new parties have also entered the scene. The political parties' aims have shifted somewhat during the decades and now a majority of the Greenlandic political parties are actually aiming for independence. There is, however, still a division between unionists on the one hand and separatists on the other hand. Sometimes this is coined as “the paradox of federalism”, where we have various groups with different aims. Some ‘groups’ would be aiming for staying within the union or federal state, while others would be working towards secession and these fractions amongst the population might cause tensions on the political scene5. This can be illustrated by figure 1 below.

Figure 1: Party Positions in Greenland

Source: Ulrik Pram Gad: 'Ahead of snap elections, Greenland's independence ambitions could open a window for closer co-operation with EU', http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/2014/10/31/ahead-of-snap-elections-greenlands-independence-ambitions-could-open-a-window-for-closer-co-operation-with-the-eu/ (consulted 05/10/2018). This figure shows the inter-party relations, however, Partii Naleraq should be higher on the sovereignty dimension. Two recent established parties have been included in the figure: Nunatta Qitornai and Samarbejdspartiet. Nunatta Qitornai could be placed on the sovereignty dimension together with Partii Naleraq in the middle of the continuum, while Samarbejdspartiet is a right-unionist party below Atassut.

5 As can be seen in the figure it is hard to detect exactly where on the left-right spectrum of politics the Greenlandic political parties stand. They usually have both dimensions within their political programs. On another note they also share some values with each other. What is clear is that six out of eight parties are in favor of independence or sovereignty, while only two parties can be considered unionists.

6 This article will look at the Greenlandic autonomy referendums, which has led to new status for the island within the Danish jurisdiction. First a short description of referendums in Denmark and Greenland will give some background information of how referendums can take place and then the Home Rule referendum of 1979 will be described and after that the referendum of 2008 will be highlighted. In the end the political and social consequences of the two autonomy referendums will be outlined followed by a conclusion to sum up the article and give some future perspective on the matter.

1. Referendums in Denmark and Greenland

7In Denmark, both binding and advisory referendums are common. Binding referendums are mandatory, when the Danish Constitution should be amended or if one wants to change the voting age. Other circumstances are when Denmark is transferring its sovereignty in one way or another, as for example, has been done in relation to the EU. If there is support of 1/3 of the Danish Parliamentarians (i.e. 60 members) who wish that the population should participate in a referendum of a legal act or bill it is also possible to arrange a referendum for that. A last possibility of having a referendum is when the country is entering into international treaties.6

8 Advisory referendums can be held when politicians on the state, regional and municipal level like to ask the people's advice. These referendums are only advisory and there is no obligation to follow the result, however, research has shown that the results of advisory referendums usually are followed by the entities. The Danish Parliament has used this in 1986, when the electorate was voting on the European Community package. Regions and municipalities have also the possibility to use advisory referendums on local matters. Some municipalities used this opportunity when there was the reform of fusing municipalities together in 2007.7

9 Denmark has used a mandatory constitutional referendum back in 1915 as a compensation for the abolition of the requirement that constitutional changes should be passed in two subsequent parliaments. In 1953, various forms of law controlling referendums were adopted in conjunction with the abolition of the upper chamber of the parliament.8

10 Referendums are required when transferring sovereignty especially in relation to EU matters in Denmark. According to §20 of the Danish Constitution measures of transferring sovereignty to the EU level have to be ratified either by the Parliament with a 5/6 majority or by voters in a binding referendum.9

11 In Greenland only advisory, ad hoc referendums are possible. The subject is decided beforehand by the Government, Parliament or the municipality on what the people should take a stand on. There have only been five referendums in Greenland so far. Apart from the two autonomy referendums, which are analyzed in more detail in this article, a referendum on ban on alcohol was introduced in 1978 and the referendum of leaving the EEC (European Economic Community) was held in 1982. Apart from that Greenland had a referendum already back in 1972 about joining the EEC with a negative outcome, but that was not acknowledged by Denmark at the time due to Greenland's status as an amt (county). After three years of negotiations after the referendum in 1982 Greenland left the EEC in 1985.10 Greenland then became an OCT-country and has bilateral agreements with the EU, which give the island direct access to several EU-programs.

2. The Referendum of 1979

12Greenland had been a county since 1953 as an integral part of Denmark. This status was merely of administrative character and Greenland was therefore under the power of the Danish Kingdom. The introduction of Home Rule in May 1979 ended this status and a new era began. Until 1979 members of the Greenlandic council were mostly elected as independent persons without any party affiliation. In the 1960s and 1970s political parties started to emerge as previously mentioned in the introduction. With the new Home Rule Act in 1979 a legislative assembly was established and for the first time elections were held with candidates representing various political parties.11

13 The background for the change of status can be drawn from the Danish government (Anker-Jørgensen-Government), which in January 1973 was putting down a committee with only Greenlandic representatives to discuss the Home Rule question. Amongst the Greenlandic politicians a discussion was to go for a similar model as the Faroe Islands had already implemented back in 1948. This discussion was done amongst the political elite in Greenland. The mandate for the committee was quite broad and the idea was to come up with a proposal of how the Greenlandic council could receive more influence and responsibility over the future development and administration within the Danish Realm.12 The initiative was from the Danish side to investigate the question of association between Denmark and Greenland.13

14 The committee came with its proposal and interim report in the beginning of 1975. As a result the new Danish government with Jørgen Peder Hansen as Minister of Greenland was then establishing a joint Danish-Greenlandic Home Rule Commission. Negotiations followed between representatives from both the Danish Government and Greenland and the result was a proposal for a new Home Rule arrangement. The arrangement as such was not based on an international treaty or amendment of the Danish Constitution, but established by the passing of an ordinary statute by the Danish Parliament, the Home Rule Act 1979, and further endorsed in a referendum held in Greenland.14

15 The referendum in Greenland was only advisory and established to view the public opinion in the nation in January 1979. The Home Rule Act was supported by 70 per cent, while 26 per cent was voting against the law. Four per cent of the votes were invalid or blank votes. The voter turnout was lying at 63 per cent due to bad weather conditions at the time. Both the larger parties: Atassut and Siumut were in favor of Home Rule, while the smaller party at the time, Inuit Ataqatigiit, was against the proposal. Inuit Ataqatigiit was in favor of independence and the party considered that Home Rule was not enough. With the new Home Rule Act, Greenland was considered as a special community within the Danish Kingdom.15

16 In accordance with the Home Rule Act, the Danish governor in Nuuk was replaced by a commissioner appointed by the Danish government. The so called rigsombudsmand (commissioner) was and still is responsible for matters not transferred to Greenlandic authorities. The rigsombundsmand is supervising that Greenland is following the Danish constitution. In accordance with the Home Rule Act several matters were transferred to the newly established legislative and executive authorities in Greenland. It was now possible for the Greenlanders to vote for own representatives to the Greenlandic parliament (Landstinget). The electoral system accepted all Danish citizens who had lived permanently in Greenland for six months prior to the election. The voting age became the universal one of 18 years of age. With the voting rights also the right to stand as a candidate was included.16

17 With the Home Rule Act Greenland was acting as an administrative region with some legal responsibilities, but it was the Danish Parliament which allocated the powers to the Greenlandic authorities. The Danish state was in charge of foreign and security matters, police, court system and monetary issues and also a lot of tasks within the social and health area. The field of natural resources was jointly administrated between Denmark and Greenland according to a 50/50 system. Economically Greenland was and still is dependent on the Danish block grant.17 The block grant is an economic support for running the Home Rule/Self-Government. It is covering the overall administrative and legal authorities.

18 The Home Rule arrangement gave Greenland and Greenlanders more confidence in how to run the region and to be in charge of its own internal affairs. Prior to the Home Rule, everything had been steered through Copenhagen.

3. The Referendum of 2008

19In 1999, the Home Rule Government established a Commission on Self-Government to investigate the possibility of achieving a higher degree of independence. The Commission on Self-Government 1999-2000 was based on the political coalition between Siumut and Inuit Ataqatigiit. Various working groups with politicians, experts and other stakeholders began to work on the issues of competences that already had been taken over, issues where the state had control and issues where joint administration prevailed in order to detect possibilities for a new partnership agreement with Denmark in order to enhance self-government. The Commission was working with six models: independence, union with another state, free association, federation, enhanced self-government for indigenous peoples and full integration. The result of the Commission's work was to go for enhanced self-government with elements to self-determination for future prospects.18

20 In early 2004, representatives of the Greenland Home Rule Government met with the Danish Prime Minister to present their views for the work ahead. Following the negotiations between the Danish and Greenlandic Governments, a Greenlandic-Danish Commission was installed. The Commission was presenting its work and recommendations in April 2008 on which the referendum was based, supported by the Danish Parliament.19

21 The referendum regarding the new self-government in Greenland was held on 25 November 2008. The people voted in favor of the new status with about 75 per cent support (63 per cent in Nuuk) and the overall turnout reached 72 per cent. Prior to the referendum, the then Greenlandic Premier, Hans Enoksen, had clarified that the event would not entail a withdrawal from the Danish Realm and he further announced a launch of an information campaign on the issue of self-government. This campaign included town hall meetings throughout the nation.20

Table 1: The results of the referendum 2008

|

Votes |

Total |

Percentage |

|

Yes |

21,355 |

75.54% |

|

No |

6,663 |

23.57% |

|

Invalid or blank votes |

250 |

0.89% |

|

Voter turnout |

28,268 |

71.96% |

Source: 'Greenland's Referendum on Home Rule, https://www.danishnet.com/government/greenlands-referendum-home-rule/ (consulted 10/8/2018); Göcke (K.), 'The 2008 Referendum on Greenland's Autonomy and What It Means for Greenland's Future', Heidelberg Journal of International Law, Vol. 69, n°1, 2009, 103.

22 The referendum was non-binding, however, the Danish parliament promised to honor the results and new negotiations between the Government of Greenland and the Danish Government followed. The Self-Government Act included new areas of competences expanding the Greenlandic power in fields that had been in Danish hands or jointly administrated before. A specific area of importance was the transfer of the natural resources that had been jointly administrated between Greenland and Denmark prior to the referendum. Another field of importance where Greenland also received more power was within foreign policy. It was now possible for Greenland to enter into bilateral agreements with other countries and to become a full member in international organizations of vital importance for Greenlandic affairs, where non-state actors are allowed, such as, the Arctic Council and the Nordic Council (member since 1984). Representatives of the Government of Greenland can also be appointed to diplomatic missions of the Kingdom of Denmark for particular matters that relates to the Self-Government authorities.21 Greenland has its own diplomatic missions in Copenhagen, Brussels, and Washington D.C. There are also proposals to open diplomatic representations in Reykjavik (October 2018) and Beijing in the near future.22

23 The status of Greenland was also changed somewhat to be illustrated by the preamble in the Self-Government Act as Greenlanders became recognized as a people according to international law with the right to self-determination. This means that the Greenlanders can secede from the Danish Realm in the future if the population so desires.23 This would then be done through a referendum and thereafter new negotiations with Denmark would probably be the result of the endeavor.

4. Political and Social Consequences of the Referendums of 1979 and 2008

24From 1979 to the late 1990s almost all 17 major areas listed in the Home Rule Act had been taken over by the Greenlandic authorities. Among these areas we find: education, the health system, social affairs, housing, infrastructure, the economy, taxation, fisheries, hunting and agriculture, the labor market, commerce and industry, the environment, the municipalities, culture, the church etc. The Home Rule system was a significant process in formulating Greenland's own competences and authority over its own internal affairs.24

25 However, the transferring of powers has not been without problems. It is still valid that the economy is very one-sided towards fisheries, which account for over 80 per cent of total exports. The block grant from Denmark constitutes about 30 per cent of Greenland's GDP. The Home Rule system, which was introduced in 1979, was a Nordic-style cabinet parliamentarian system and a lot of employees working within the Greenlandic government are coming from Denmark. The Greenlandic society is still facing a lot of social problems due to a colonial past, such as, alcoholism, high rates of suicide, domestic violence, child abuse, etc. Another problem is the lack of trained and educated people in respect of the numerous areas of society in need of attention.25

26 The current Self-Government Act of 2009 contains 29 sections, excluding the preamble. In the appendices, the Act has two lists including 33 areas of responsibility that can be taken over by Greenland from the Danish state one by one whenever Greenland feels ready for it. In List I five areas are mentioned (i.e. industrial injury compensation, remaining areas of health care, the road traffic, the law of property and obligations, the commercial diving area), which can be taken over immediately by the Greenlandic authorities, while List II needs further negotiations with Denmark.26 When such areas are taken over, the legislative and executive power, the financing and the administration over the field in question becomes Greenland's responsibility.27

27 Under Self-Government Act of 2009, Denmark retains the control of the Constitution, citizenship, Supreme Court, foreign affairs, defense and currency. However, Denmark is expected to involve Greenland in foreign affairs and security matters that affect Greenland or are of vital importance for Greenland.28

28 As mentioned earlier one of the largest changes between the Home Rule Act of 1979 and the Self-Government Act of 2009 relates to economic matters. The block grant is now fixed at about DKK 3.4 billion (about EUR 456 million) according to 2009 prices. There is an annual adjustment in relation to inflation.29 Furthermore, there is a legal mechanism regarding the field of natural resources, where the level of the block grant will be reduced by an amount corresponding 50 per cent of the earnings from minerals and energy extraction once they exceed DKK 75 million (about EUR 10 million). Future revenues from eventual oil and mineral extraction will then be divided between Greenland and Denmark, while the block grant is reduced further and in the end it eventually will be phased out.30

29 Regarding the language issue, the Greenlandic language is now stated as the official language in the Self-Government Act of 2009, while in the Home Rule Act of 1979; the Greenlandic language was seen as the main language where also Danish have to be taught in the schools.31 Now the politicians have been discussing to replace Danish with English as the first foreign language to be taught in the elementary schools. This is part of the new Government's aim. Another matter to mention is that the Greenlandic names for both parliament and government have been introduced in the Act as Inatsisartut and Naalakkersuisut are mentioned respectively to give a sign that the Act has become more Greenlandic.32 During the Home Rule era a "danization" period was present, while the Self-Government process is a clear "greenlandization" period.

30 In relation to the Danish Constitution there is no obstacle for Greenland to become independent. The Danish Constitution will not have to be amended, since neither Greenland nor the Faroe Islands are entrenched in the Constitution. §19 of the Constitution envisages the possibility that the government can conclude treaties diminishing the territory of the Realm, and such treaties only require the acceptance of the Parliament to be ratified. Constitutionally it would be a fairly simple process to grant Greenland or the Faroe Islands independence. The §§ where Greenland and the Faroe Islands are mentioned will simply cease to exist if this would happen.33

31 The introduction of Self-Government has changed the legal platform and has given Greenlanders the ability to more easily address the new challenges facing a modern Greenlandic society. However, Greenland faces challenges when it comes to the fields of education, social policy, health, industrial development, the labor market and foremost the economy.34 The largest dilemma is to find a balance between the pressing need for new revenues, for diversifying the economy and to engage in extractive industries, while at the same time meet the high environmental and societal standards so that the Inuit traditional subsistence economy with hunting and fisheries can sustain.35

32 Politically there has been a dispute regarding the Constitutional Commission, which was established in 2017. The political members have been replaced and there have been controversies of how to frame a Greenlandic Constitution for the future. The idea is to come up with a Greenlandic Constitution, but the question has been if this should be in accordance with the Danish Constitution as a "free association model" or if the Constitution should be for a total break away from Denmark.36 Some politicians are in favor of a two-step solution, where free association would be the first step and then full independence would follow, while others are more in favor of a direct state Constitution. "The paradox of federalism" is evidently at play within the Greenlandic society.37 Some politicians are in favor of unionism and others of secession. The autonomy referendums have so far led to further self-government, but the next step towards independence seems to cast doubt amongst both politicians and ordinary people.

33 Regarding the support for an independent Greenland some opinion polls from 2002 and 2017 show that the support has declined. In 2002, 61 per cent was in favor of independence, while in 2017 it had dropped to 44 per cent. However, these opinion polls should be taken with a pinch of salt since only 700 people have been taken into consideration as a random sample of persons over 18 years of age. The persons have also been answering questions where the alternatives have been very close to each other, so it is hard to detect if the population actually is leaning more towards independence than not.38 The decline can be interpreted as the population has realized that independence lies far away at the moment and if Greenland is not getting its economy running the aim for independence would be an impossible objective to reach. A small population size is another factor to bring into the mix, especially in a large island region as Greenland, where people are widely scattered across the nation.

Conclusion

34Greenland's transition from a colony back in 1721-1953, then county status from 1953-1979, Home Rule from 1979-2009 and now the process of Self-Government has changed the Greenlandic society from a traditional hunting and gathering society into a fishery nation with huge potential to become a mining nation in the future. There are large mining projects awaiting for the green light to become realized when prices for raw materials are at a stage they were back in 2013. The political debate has been focused around sovereignty and independence, especially in the latest election campaign from 2018. There is certainly a political will to become independent in the future; however, there are still many challenges to overcome and to get Greenland on the right track specifically within the economic sphere. A lot of work is being done, but many matters prevail to be solved, especially within the social and structural field. There are huge distances along the coast of the country with no roads connecting the towns or settlements. The only way to get around is by air plane or boat. This means, of course, that there are still huge differences between the communities in the whole nation. Some are more modern, Scandinavian like, while others are still living in the past where time has stand still for a long period. However, urbanization is a phenomenon also in the Greenlandic context, where people are on the move from the settlements into the towns. This has led to a shortage of housing in the towns, were a lot of construction works are underway.

35 Greenland is strategically developing to take more matters in its hand as the Self-Government Act of 2009 allows. Some politicians have recently debated that it is taking too long for Greenland to really get all things done necessary to fulfill the aims of the Act. Others are criticizing that the Greenlandic Government is not doing its job to enhance the economic possibilities in the country, which would establish new companies and new work places for the population. Whatever view anyone has, the development that has shaped the Greenlandic society of today is extraordinary. It is seldom a former colony has developed in such a rapid pace to become a functional and in most cases modern society on par with any other Nordic society.

36 Only time will tell if a new referendum will come into place. The next referendum will probably be about independence. If autonomies, such as, the Faroe Islands, Scotland and Catalonia also try to pursue for independence once again and make it successful, then Greenland would probably follow suit. Greenland could also be the first region to succeed in such an event, but there is no doubt that every autonomous region is still in the waiting room for what the future will bring. It is hard to predict the future, since island politics can shift very quickly from pro-independence to pro-unionism. "The paradox of federalism" is therefore always present.

Notes

1 Skydsbjerg (H.), Grønland 20 år med hjemmestyre. Nuuk: Atuagkat, 1999.

2 Ackrén (M.), 'Greenland's Electoral Results 1979-2013 - an overview', p. 168 in Grønlandsk Kultur- og Samfundsforskning 2013-14, Bind 1. Nuuk: Ilisimatusarfik/Forlaget Atuagkat, 2014.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 Erk (J.) and Anderson (L.), 'The Paradox of Federalism: Does Self-Rule Accommodate or Exacerbate Ethnic Divisions?', Regional & Federal Studies, vol. 19, n°2, 2009, pp. 191-202. Here “paradox of federalism” is used in a more general manner than was originally stated or thought of by the authors. It could equally be seen as “the paradox of union” in this particular context.

6 'Folkeafstemninger/Folketinget', https://www.ft.dk/da/Folketsyret/Valg og afstemninger/Folkeafstemninger (consulted 21/8/2018).

7 Ibid.

8 Setälä (M.), 'Referendums in Western Europe - A Wave of Direct Democracy?', Scandinavian Political Studies, vol. 22, n°4, 1999, p. 330. During a period from 1940 to 1998 Denmark has had 15 referendums in total.

9 Beach (D.), 'Referendums in the European Union', Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics, 2016, http://politics.oxfordre.com/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.503 (consulted 10/8/2018). DOI: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.503.

10 For more information on that topic, see e.g. Gad (U.P.), 'Greenland projecting sovereignty - Denmark protecting sovereignty away' in Adler-Nissen (R.) and Gad (U.P.) (eds.), European Integration and Postcolonial Sovereignty Games, London and New York, Routledge, 2013, pp. 217-234.

11 Lyck (L.) and Taagholt (J.), 'Greenland - Its Economy and Resources', Arctic, vol. 40, n°1, 1987, p. 52.

12 Villaume (P.), 'Fra amt til hjemmestyre' i Gyldendals og Politikens Danmarkshistorie, Olaf Olsen (red.), 2002-2005, http://denstoredanske.dk/index.php?sideId=306552 (consulted 12/8/2018).

13 Grønlandsk-dansk selvstyrekommissions betænkning om selvstyre i Grønland, april 2008, p. 9.

14 Göcke (K.), 'The 2008 Referendum on Greenland's Autonomy and What It Means for Greenland's Future', Heidelberg Journal of International Law, vol. 69, n°1, 2009, p. 106.

15 Villaume (P.), op.cit.

16 Ackrén (M.), 'Grönlands politiska utveckling efter andra världskriget till våra dagar', p. 93 i Sia Spiliopoulou Åkermark och Gunilla Herolf (red.), 'Självstyrelser i Norden i ett fredsperspektiv - Färöarna, Grönland och Åland', Mariehamn: Nordiska Rådet och Ålands fredsinstitut, 2015.

17 Jónsson (I.), 'From Home Rule to Independence - New Opportunities for a New Generation in Greenland' in Petersen (H.) and Poppel (B.) (eds.), Dependency, Autonomy, Sustainability in the Arctic, Aldershot-Brookfield, Ashgate, 1999, pp. 171-192.

18 Betænkning afgivet af Selvstyrekommissionen, marts 2003, Nuuk: Grønlands hjemmestyre.

19 Göcke (K.), op.cit., p. 110.

20 'Greenland's Referendum on Home Rule', https://www.danishnet.com/government/greenlands-referendum-home-rule/ (consulted 10/8/2018).

21 Göcke (K.), op.cit., pp. 107-109.

22 Ackrén (M.), 'Diplomacy and Paradiplomacy in the North Atlantic and the Arctic - A Comparative Approach' in Finger (M.) and Heininen (L.) (eds.), The Global Arctic Handbook, Switzerland, Springer, 2018, p. 241.

23 Ackrén (M.), 'Island Autonomies - Constitutional and Political Developments' in Karlhofer (F.) and Pallaver (G.) (eds.), Federal Power-Sharing in Europe, Baden-Baden, Nomos, 2017, p. 237.

24 Kleist (M.), 'Greenland's Self-Government' in Loukacheva (N.) (ed.), Polar Law Textbook, TemaNord 2010, Copenhagen: Nordic Council of Ministers, 2010, pp. 171-174.

25 Ibid., pp. 174-175; Kuokkanen (R.), 'To See What State We Are In': First Years of the Greenlandic Self-Government Act and the Pursuit of Inuit Sovereignty, Ethnopolitics, vol. 16, n°2, 2017, pp. 180-185.

26 Act on Greenland Self-Government, Act no. 473 of 12 June 2009. Available at: https://naalakkersuisut.gl//~/media/Nanoq/Files/Attached%20Files/Engelske-tekster/Act%20on%20Greenland.pdf

27 Kleist (M.), op.cit., p. 179; see also Kuokkanen (R.), op.cit., p. 183.

28 Kuokkanen (R.), op.cit., p. 183.

29 Ackrén (M.), op.cit. (2017), p. 238.

30 Nuttall (M.), ' Self-Rule in Greenland - Towards the World's First Independent Inuit State?', Indigenous Affairs, N° 3-4, 2008, p. 65.

31 Kleist (M.), op.cit., p. 191.

32 Ibid., p. 184.

33 Albæk Jensen (J.), 'The Position of Greenland and the Faroe Islands Within the Danish Realm', European Public Law, vol. 9, n°2, 2003, p. 178.

34 Kleist (M.), op.cit., p. 195-196.

35 Kuokkanen (R.), op.cit., p. 188.

36 Hovgaard (G.) and Ackrén (M.), 'Autonomy in Denmark: Greenland and the Faroe Islands', in Muro (D.) and Woertz (E.) (eds.), Secession and Counter-Secession: An International Relations Perspective, Barcelona, CIDOB, 2018, p. 74; Ackrén, (M.), 'Greenland', Online Compendium Autonomy Arrangements in the World, November 2017, at www.world-autonomies.info.

37 For a more detailed description of "the paradox of federalism", see Erk (J.) and Anderson (L.), 'The Paradox of Federalism: Does Self-Rule Accommodate or Exacerbate Ethnic Divisions?', Regional & Federal Studies, vol. 19, n°2, 2009, pp. 191-202.

38 See Sermitsiaq (newspaper), lørdag 1. april 2017. 'Selvstændighed kun uden forringelse'. (Sermitsiaq, Saturday 1 April 2017. 'Independence only without worse conditions'). Available: http://sermitsiaq.ag/selvstændighed-kun-uden-forringelser (consulted 30/10-2017).