- Accueil

- Volume 28 (2025)

- number 3-4

- Taxonomic revision and new elasmobranch records from the Wemmel Sand and Asse Clay members, base of the Maldegem Formation (middle Lutetian, southern North Sea Basin)

Visualisation(s): 1054 (12 ULiège)

Téléchargement(s): 631 (4 ULiège)

Taxonomic revision and new elasmobranch records from the Wemmel Sand and Asse Clay members, base of the Maldegem Formation (middle Lutetian, southern North Sea Basin)

Document(s) associé(s)

Annexes

Abstract

The elasmobranch fauna of the middle Lutetian Asse Clay Member (the lower part of the Maldegem Formation) has been updated and complemented with new material from a temporary outcrop at Papenboskant (Wolvertem), about 20 km north of Brussels. This faunal assemblage, which exclusively comes from its coarse-grained glauconitic base, traditionally known as the bande noire, comprises 22 taxa. Fourteen are mentioned for the first time in this horizon, including Abdounia lapierrei, which has never been recorded in Belgium before, and Casierabatis spp. The latter comprises dental morphologies deviating from these of the two nominal Casierabatis species known to date, although it is currently unclear if these reflect intraspecific variability or represent taxonomic novelties. The new records from Papenboskant consist predominantly of small-toothed taxa, mainly batoids, which are absent from the historical handpicked museum collections of the Wemmel Sand and Asse Clay members reviewed in this study. The composition of the elasmobranch fauna indicates that during the middle Lutetian, the area north of Brussels was covered by a tropical to warm-temperate shallow sea with sandy to muddy bottoms and an open connection to deeper waters. The pronounced similarities between the assemblages of the Belgian, Hampshire, and Paris basins indicate that, during the middle and late Lutetian, these three subareas of the southern North Sea remained interconnected and maintained marine exchange with the Atlantic Ocean, not only through the northern seaway but also via the southwestern English Channel. Virtually all of the newly recovered elasmobranch taxa existed over a considerable period of time and were reported from several Ypresian and/or Lutetian deposits across the North Sea Basin. Abdounia lapierrei appears to possess biostratigraphic significance, being so far confined to Lutetian strata. This may also apply to certain representatives of the Casierabatis species group, although this remains to be confirmed. The single tooth of Notorynchus figured in Leriche (1905) and recovered from the Wemmel Sand Member at Neder-Over-Heembeek is re-examined and refigured. This specimen represents the first occurrence of Notorynchus kempi in Belgium.

Table des matières

1Dr Jacques Herman (former staff member of the Belgian Geological Survey, †2022) documented and sampled the temporary outcrop studied herein and preserved the recovered fossils, including the elasmobranch teeth. This paper is dedicated to his memory in recognition of his lifetime contributions to elasmobranch palaeontology and his enduring passion for the Belgian Palaeogene.

1. Introduction

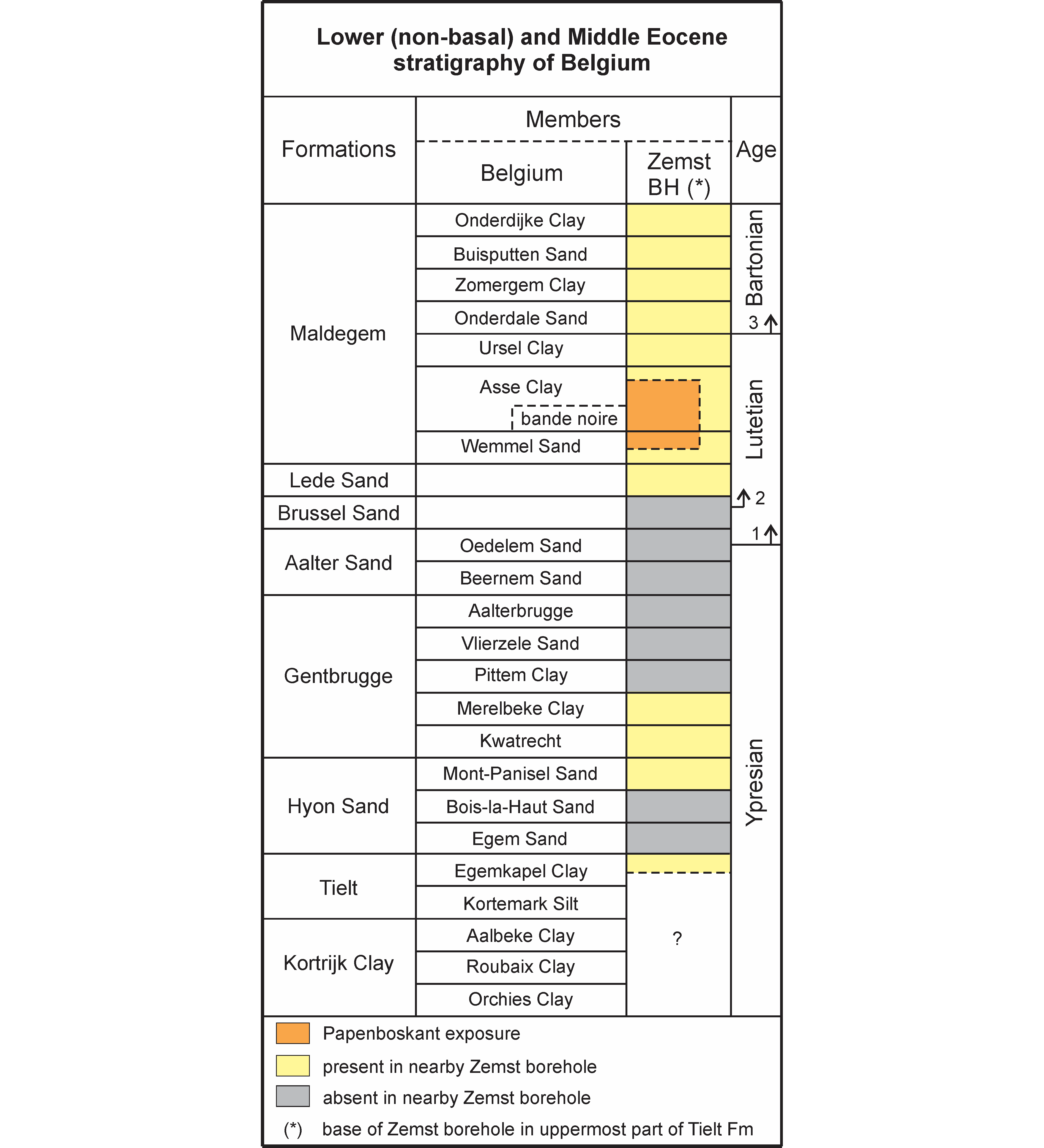

2The Belgian Basin is well suited for palaeobiodiversity and palaeoenvironmental studies of Eocene strata because of the numerous fairly complete sections with well-documented integrated sequence stratigraphy and often abundant fossil content (e.g. Steurbaut, 1998; Vandenberghe et al., 2004; Iserbyt & De Schutter, 2012; Steurbaut & Nolf, 2021). Many of these focused on the Ypresian (Dupuis et al., 1991; Steurbaut, 2006; Steurbaut & King, 1994, 2017), which is renowned for its rich and highly diversified elasmobranch fauna, resulting from extensive sampling over the last decades (e.g. Casier, 1946, 1950; Nolf, 1972; Herman, 1975, 1977, 1979, 1982a, 1982b, 1984, 1986; Smith et al., 1999; Iserbyt & De Schutter, 2012; Migom et al., 2021; Reinecke et al., 2024). Among the most thoroughly investigated localities for shark tooth collecting in the Ypresian are the Marke clay pit (several levels within the Roubaix Clay Member; Steurbaut & King, 2017, figs 6 a, b, c) and the Egem sandpit (base of the Egemkapel Clay Member and several levels in the overlying Egem Sand Member; Steurbaut, 1998, 2006, 2015) (Fig. 1).

3Elasmobranch faunas from overlying middle and upper Eocene strata of Belgium are less understood, except these from some exceptionally rich levels within the middle Lutetian. Steurbaut & Nolf (2021) recently recalibrated the onset of the Lutetian as the result of high-resolution correlations between the historical Lutetian stratotype in the Paris Basin and a series of well-dated sections across NW Europe. The Ypresian–Lutetian boundary sensu Steurbaut & Nolf (2021), dated at 49.11 Ma, predates the GSSP-defined base of the Lutetian Stage—initially dated at 47.84 Ma (Molina et al., 2011), but recently recalibrated to 48.07 Ma (Speijer et al., 2020; Cohen et al., 2024)—by approximately 1.1 to 1.3 Myr. As a consequence, Steurbaut & Nolf (2021) suggested redefining the Lutetian of Belgium to include the top of the Aalter Sand Formation, the Brussel Sand and Lede Sand formations, and the lower part of the Maldegem Formation (Fig. 1).

4The early Lutetian Brussel Sand Formation (calcareous nannofossil Zone NP14) and the middle Lutetian Lede Sand Formation (base Zone NP15) revealed to be exceptionally rich in selachian remains (e.g. Burtin, 1784; Winkler, 1873, 1874b; Leriche, 1905, 1906, 1951; Casier, 1949; de Meijer, 1973a, b; Nolf, 1973, 1988; Herman, 1975, 1982a; Taverne & Nolf, 1979; Cappetta & Nolf, 2005; Mollen, 2008; Van Den Eeckhaut & De Schutter, 2009). The younger Lutetian shark faunas, which are poorly represented in the historical museum collections of Belgium, and have received little attention to date (Leriche, 1905, 1906, 1939; Casier, 1966), are reviewed herein. However, the main focus of this paper lies on the exceptionally rich elasmobranch fauna of Papenboskant, recovered from the glauconitic base of the middle Lutetian Asse Clay Member, traditionally known as the bande noire (literally the black band).

Figure 1. Stratigraphic position of the Papenboskant exposure relative to the nearby Zemst borehole (after Steurbaut et al., 2015). (1) = Ypresian–Lutetian boundary sensu Steurbaut & Nolf (2021); (2) = GSSP-defined base of the Lutetian Stage according to Molina et al. (2011); (3) = base of the Bartonian according to De Coninck (1995). Basal Ypresian units omitted; Kortrijk Clay Formation grades laterally in central Belgium into a sandy succession, the upper part of which represents the Mons-en-Pévèle Sand Formation (Steurbaut et al., 2017). Abbreviations: BH, borehole; Fm, Formation.

2. Locality and material

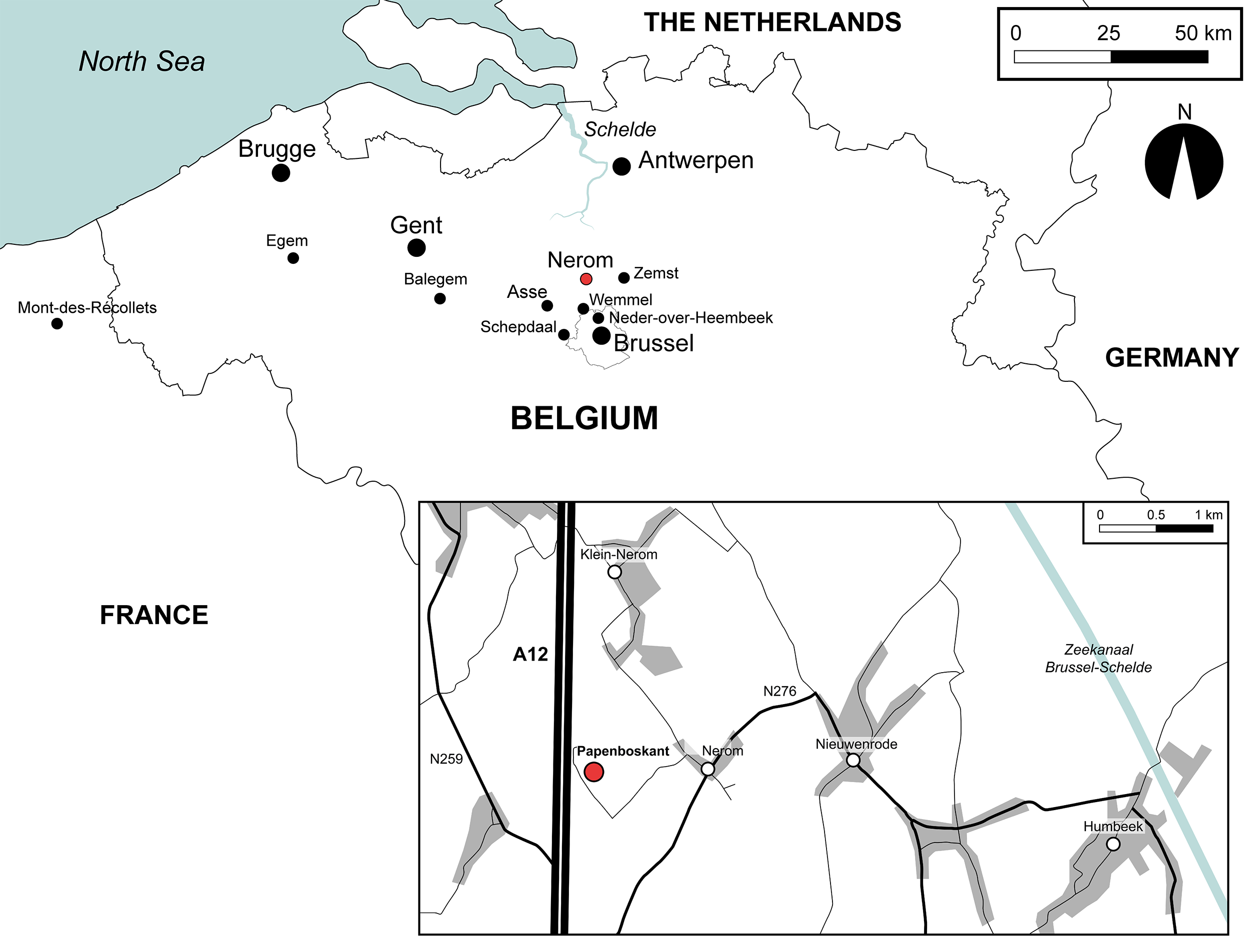

5The material studied in this paper was collected by the late Dr Jacques Herman in early 1998 in a temporary exposure dug out by Distrigas (now Eni Gas & Power NV/SA) at Papenboskant (see Supplementary material for an overview of the excavation activities). This site is located on the hamlet of Nerom (village of Wolvertem, now municipality of Meise, Vlaams-Brabant, northern Belgium), about 50 m from the highway A12 Brussel–Antwerpen and approximately 12 km NE of Asse (x = 146.350, y = 185.300; WGS84 coordinates 50°58’40.57” N, 4°19’0.41” E; Fig. 2). It is registered at the Belgian Geological Survey (BGS) as 73W324. The material figured was collected from the glauconitic base of the Asse Clay Member. Approximately 1200 kg of this horizon was screen-washed using a sieve with 0.5 mm mesh. It is deposited in the collections of the Institute of Natural Sciences (Brussels) under registration numbers IRSNB P 10774–10796. The remaining fossils (the non-figured elasmobranch teeth, teleost otoliths and molluscs) are registered under IG 34940.

3. Lithology and stratigraphy of the studied section

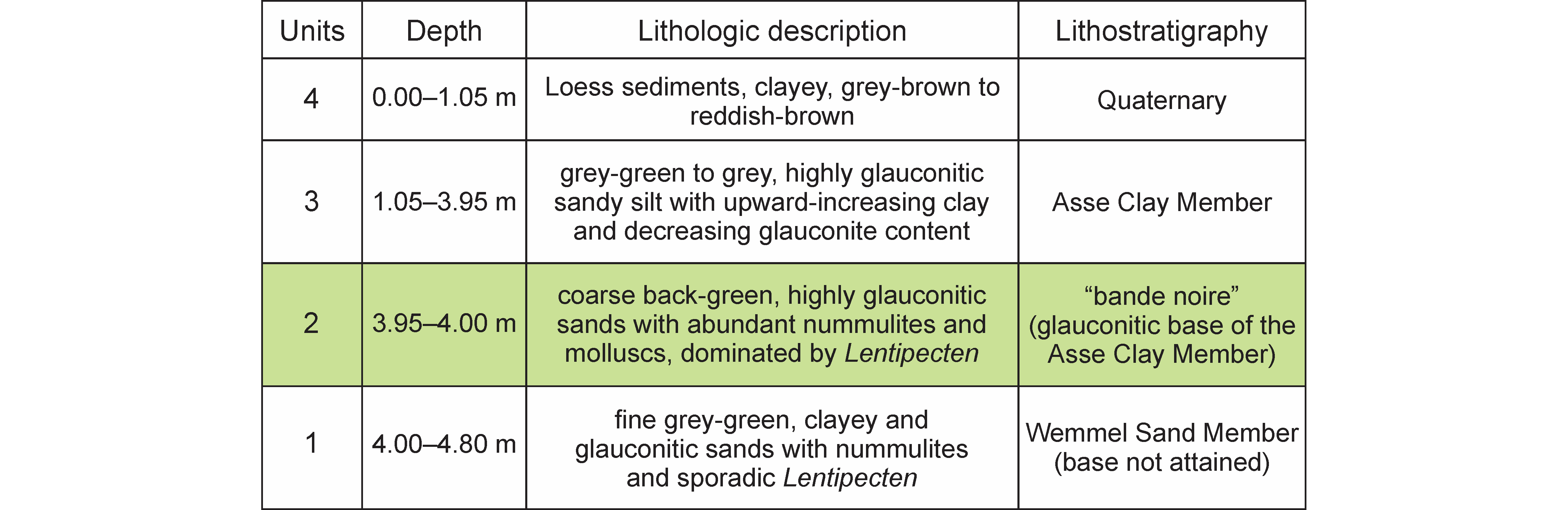

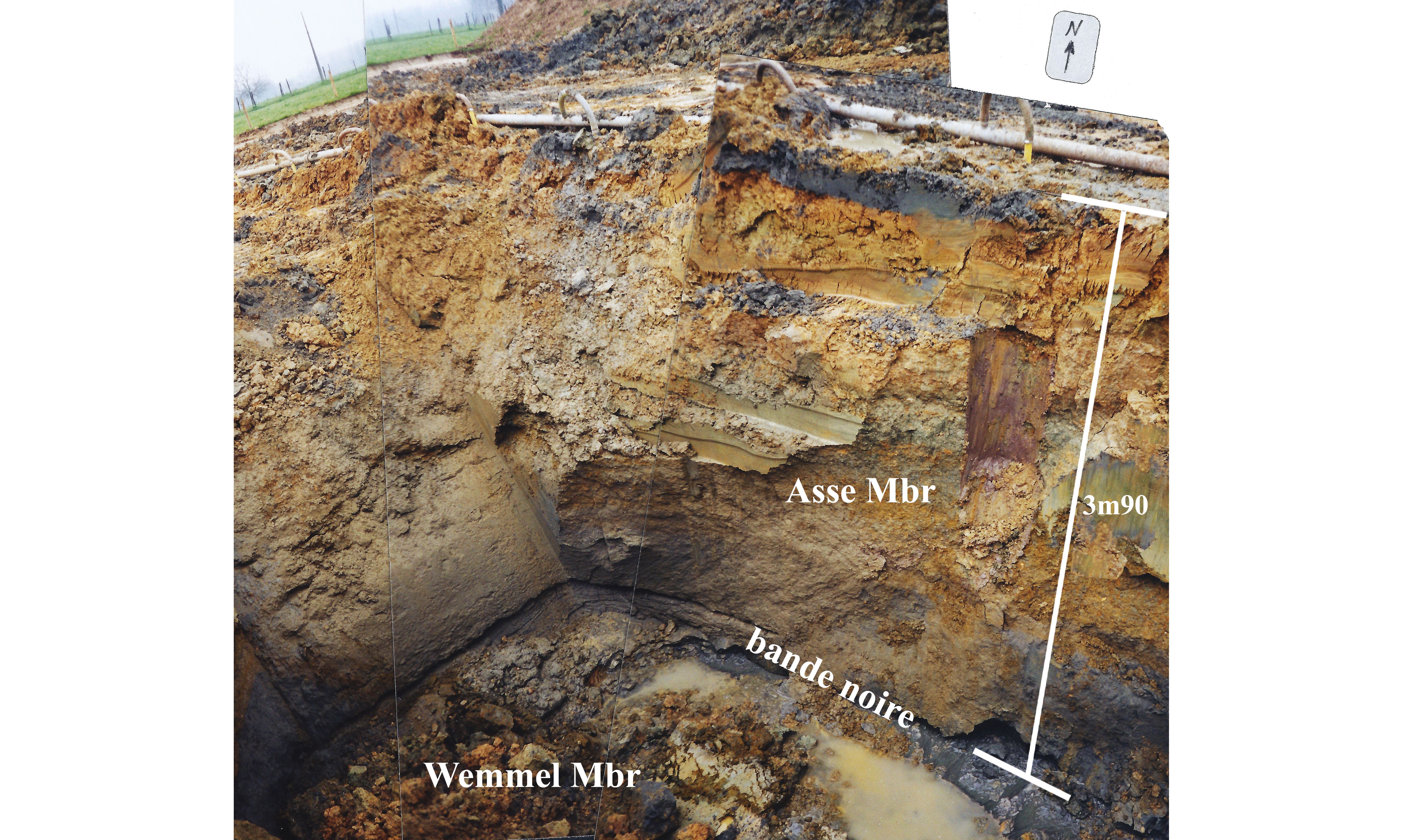

6Four units were recognised by J. Herman in the almost 5 m deep temporary excavation at the Papenboskant in Nerom (Wolvertem) (see Table 1), among which the Wemmel Sand Member (Vincent & Lefèvre, 1872) and the overlying Asse Clay Member (sensu Jacobs, 1978; before, the Asse Clay included the Ursel Clay, e.g. Conseil géologique, 1929) (Figs 2–3). Both represent the lower part of the Maldegem Formation (Jacobs & Sevens, 1993), a marine sandy-clayey succession of middle Lutetian to latest Bartonian age (e.g. Steurbaut, 2006; King, 2016) (Fig. 1).

Table 1. Lithology and stratigraphic interpretation of the Papenboskant section (extract of J. Herman’s field notebook dating back to 1998).

7The excavation at Papenboskant terminated in glauconitic clayey sand containing nummulites and rare Lentipecten, attributed to the Wemmel Sand Member (Table 1). A comparative analysis of coeval records (e.g. Kaasschieter, 1961; Jacobs, 1978; Steurbaut et al., 2015) shows that these clayey sands correlate with the upper part of the Wemmel Sand Member. Its presence at Papenboskant is not surprising as the highly fossiliferous Wemmel Sand Member has been systematically documented in the area between Asse and Zemst, north of Brussels, over the last 150 years (e.g. figuring in many publications from Vincent & Rutot, 1879 up to Steurbaut et al., 2015), yielding rich and highly diversified mollusc faunas (Glibert, 1936, 1938) and remarkable fish remains (Storms, 1896). It is presently interpreted as a single depositional sequence, assigned to the middle part of Zone NP15 and of middle Lutetian age (Steurbaut et al., 2015).

8At Papenboskant, as elsewhere between Asse and Zemst (Fig. 2), the Wemmel Sand Member is overlain by a 5 to 10 cm thick highly glauconitic coarse-grained sand (authigenic glauconite locally comprising up to 50% of the sand fraction; unit 2 of Table 1, Fig. 3). This horizon, which represents the base of the Asse Clay Member, has been identified throughout the Belgian Basin, from the Mont-des-Récollets in the SW (Lyell, 1852), through the area between Gent and Brugge (Delvaux, 1886; Hacquaert, 1936; Jacobs, 1978) to the Zemst area, north of Brussels (Steurbaut et al., 2015). The bande noire is exceptionally fossiliferous at Papenboskant (a wide variety of invertebrate taxa was recorded by J. Herman, commented on and illustrated in Supplementary material) and particularly rich in nummulites and molluscs, dominated by Lentipecten and Ostrea. Sixty-five identifiable elasmobranch teeth were retrieved through bulk sampling and screen-washing and are studied herein. The overlying interval, presenting a fining upward trend from silty glauconitic sands to silty clays with decreasing glauconite content, was attributed to the Asse Clay Member (unit 3 of Table 1). This interpretation is in line with earlier data from the type locality Asse (Jacobs, 1978; Steurbaut, 1986), the Balegem outcrop (Jacobs & Sevens, 1994), respectively about 12 km and 37 km west, and the recent investigation of the Zemst borehole, about 10 km east of the Papenboskant section (Steurbaut et al., 2015). According to Steurbaut et al. (2015), the Asse Clay Member, including the bande noire, and the overlying Ursel Clay Member (Steurbaut et al., 2015) form part of a single depositional sequence. Microfossil investigations (Steurbaut, 1986; De Coninck, 1995), especially the identification of Zone NP15 and the base of NP16, revealed that this sequence does not belong to the Bartonian, as thought up to the late 1970s (surprisingly maintained in Maréchal, 1994), but is of middle to late Lutetian age (Steurbaut, 2006; Steurbaut & Nolf, 2021) (Fig. 1).

Figure 2. Location of the temporary exposure of the Asse Clay Member at Papenboskant (hamlet Nerom, village of Wolvertem).

Figure 3. Photograph of the Papenboskant exposure taken in 1998 by J. Herman, showing stratigraphic details. Abbreviation: Mbr, Member.

4. Taxonomic notes on elasmobranchs of the Asse Member

4.1. Preliminary remarks

9As virtually all of the elasmobranch taxa from Papenboskant have been thoroughly described from many lower and middle Lutetian deposits in the southern North Sea Basin, only the most relevant information is given in the present paper. It includes technical data, such as the available material and collection numbers, and, obviously, a general discussion on the criteria used for species delimitation and assignment. When necessary, comments on taxonomic updates and distribution patterns are added.

10Systematics, morphological tooth terminology and tooth measurements follow Cappetta (2012) for the selachians and Reinecke et al. (2024) for the batomorph genera. The reader is referred to the latter for an extensive description and iconography of several batomorph species encountered in the present study. Author and publication dates of higher taxonomic levels up to species level are taken from Cappetta (2012). These data are not included in the reference list.

11Several species cited by Leriche (1905, 1906) do not figure in the species list compiled in the present paper (Table 2) as they are considered synonymous with other taxa. Physodon tertius (Winkler, 1874b) and Galeorhinus minor (Agassiz, 1843) are placed in synonymy with Physogaleus secundus (Winkler, 1874b) (e.g. Cappetta, 1980, 2012). Lamna (Odontaspis) hopei Agassiz, 1843 represents Hypotodus verticalis (Agassiz, 1843), following Cappetta & Nolf (2005) and Isurolamna inflata (Leriche, 1905) represents Isurolamna affinis (Casier, 1946), a species not yet recognised at the time of Leriche. The genus Jaekelotodus Menner, 1928 is assigned to the family Jaekelotodontidae as originally defined by Glückman (1964) and subsequently adopted by Iserbyt & De Schutter (2012) and Ebersole et al. (2024). The genus Striatolamia is assigned to the family Carchariidae, as first proposed by Cunningham (2000) and subsequently adopted by Adolfssen & Ward (2015). The use of quotation marks, before and after generic names, as proposed by Reinecke et al. (2024) (e.g. ‘Pseudobatos’ steurbauti and ‘Rhynchobatus’ vincenti) is adopted herein. Quotation marks (‘ ’) are used in taxonomy around a genus-group (or species-group) for specifying that the name is obsolete or for indicating that the species is thought to belong to a related genus or to a new genus, related to the named genus, but that the available material is insufficient for making formal decisions (Bengtson, 1988). Their use by Reinecke et al. (2024) refers to the latter. The single tooth, erroneously attributed to Notidanus primigenius Agassiz, 1843 by Leriche (1905), represents the first record of Notorynchus kempi Ward, 1979 in Belgium.

12Sixty-five teeth have been identified to at least genus level (Table 2), belonging to 17 taxa, including 14 nominal species, and two species and one species complex in open nomenclature. According to Herman’s report (‘Archives SGB 73W324’ in the file catalogue of the BGS, which is available as Supplementary material), around 20 not fully grown teeth were additionally collected from the sieve residue, but these seem to have been lost.

4.2. Order Carcharhiniformes

13Abdounia minutissima (Winkler, 1873)

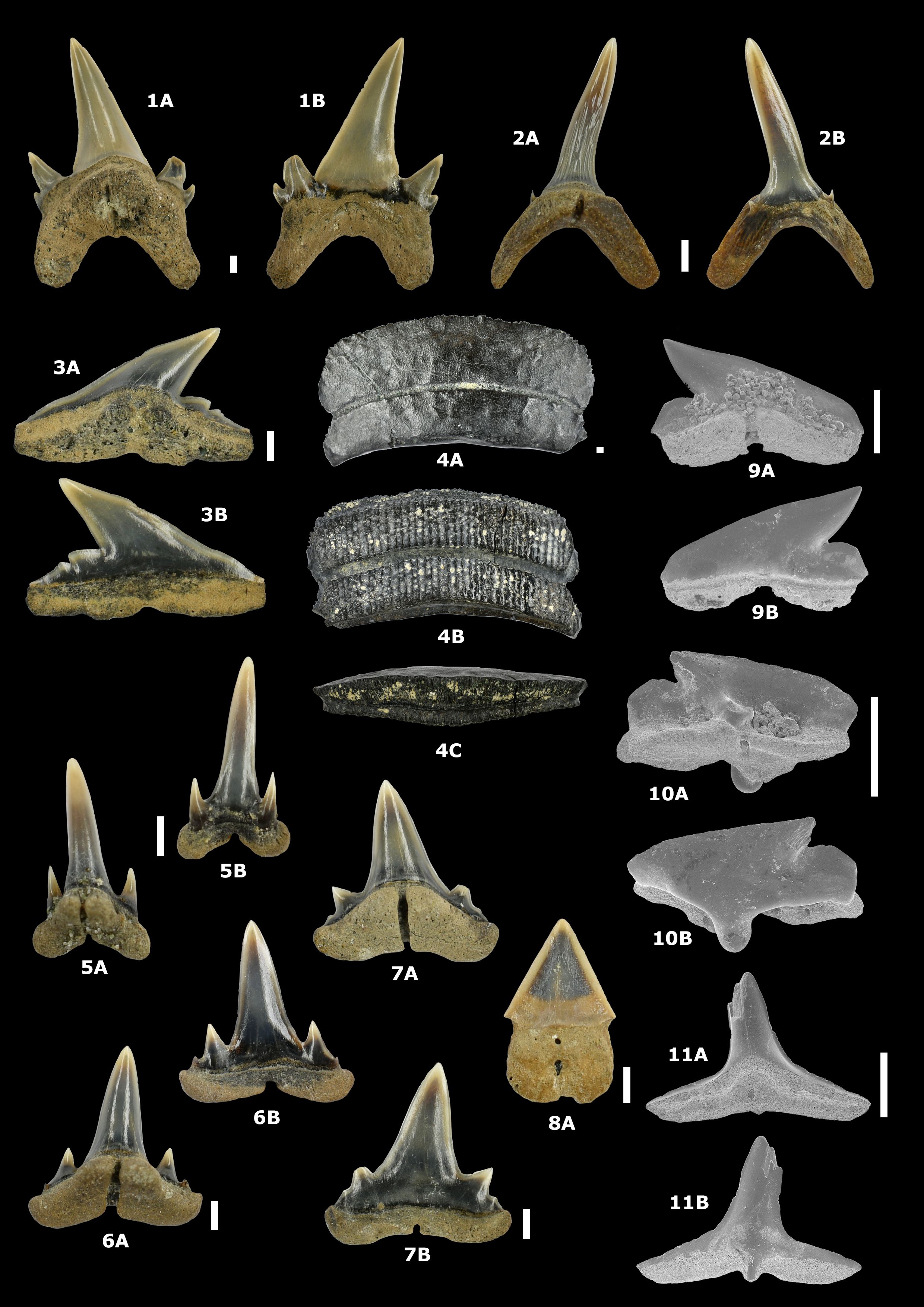

14(Pl. 1.6)

15Two teeth, including IRSNB P 10774, are attributed to Abdounia minutissima (Winkler, 1873) by the presence of a principal pair of cusplets, well separated from the main cusp, faint folds on the labial crown base and a vestigial secondary pair of cusplets, which may occur on these teeth (e.g. Leriche, 1905, pl. 5, fig. 40).

16Abdounia beaugei (Arambourg, 1935)

17(Pl. 1.7)

18A single tooth, IRSNB P 10775, is attributed to Abdounia beaugei (Arambourg, 1935) by its large size, smooth crown surface and less high crown. Among the additional characteristics are the presence of a principal pair of diverging cusplets, attached to the main cusp, and the presence of a marginal secondary pair.

19Abdounia lapierrei Cappetta & Nolf, 1981

20(Pl. 1.5)

21Two teeth, including IRSNB P 10776, are attributed to Abdounia lapierrei Cappetta & Nolf, 1981 by their tall and elongated crown marked by a single pair of sharp cusplets and by their mesio-distally compressed root. Teeth of A. lapierrei are similar to those of Abdounia enniskilleni (White, 1956), but they are smaller in size, have higher and sharper cusplets and a smooth crown surface (Cappetta & Nolf, 1981).

22Physogaleus secundus (Winkler, 1874b)

23(Pl. 1.3)

24A single tooth, IRSNB P 10777, is attributed to Physogaleus secundus (Winkler, 1874b) by the smooth mesial cutting edge and limited number of distal cusplets (Ebersole et al., 2019). As already mentioned above, Physogaleus tertius (Winkler, 1874b), listed by Leriche (1905, 1906), is regarded as junior synonym of P. secundus (e.g. Cappetta, 1980; Kent, 1999). As both morphologies are typically found together, they might well be the result of sexual dimorphism or ontogenetic change.

25Rhizoprionodon ganntourensis (Arambourg, 1952)

26(Pl. 1.9)

27Two teeth, including IRSNB P 10778, are attributed to Rhizoprionodon ganntourensis (Arambourg, 1952), the only valid Eocene member of the genus, showing a nearly circumglobal distribution in the middle Eocene (Ebersole et al., 2023). Iserbyt & De Schutter (2012) recognised the species from the lower Ypresian Roubaix Clay Member (Kortrijk Clay Formation) at Marke, representing the stratigraphically oldest R. ganntourensis find in the published record. The species is also present in the slightly younger middle Ypresian Egemkapel Clay Member (Tielt Formation) and Egem Sand Member (Hyon Sand Formation) at Egem (De Schutter, pers. obs.).

28Pachyscyllium gilberti (Casier, 1946)

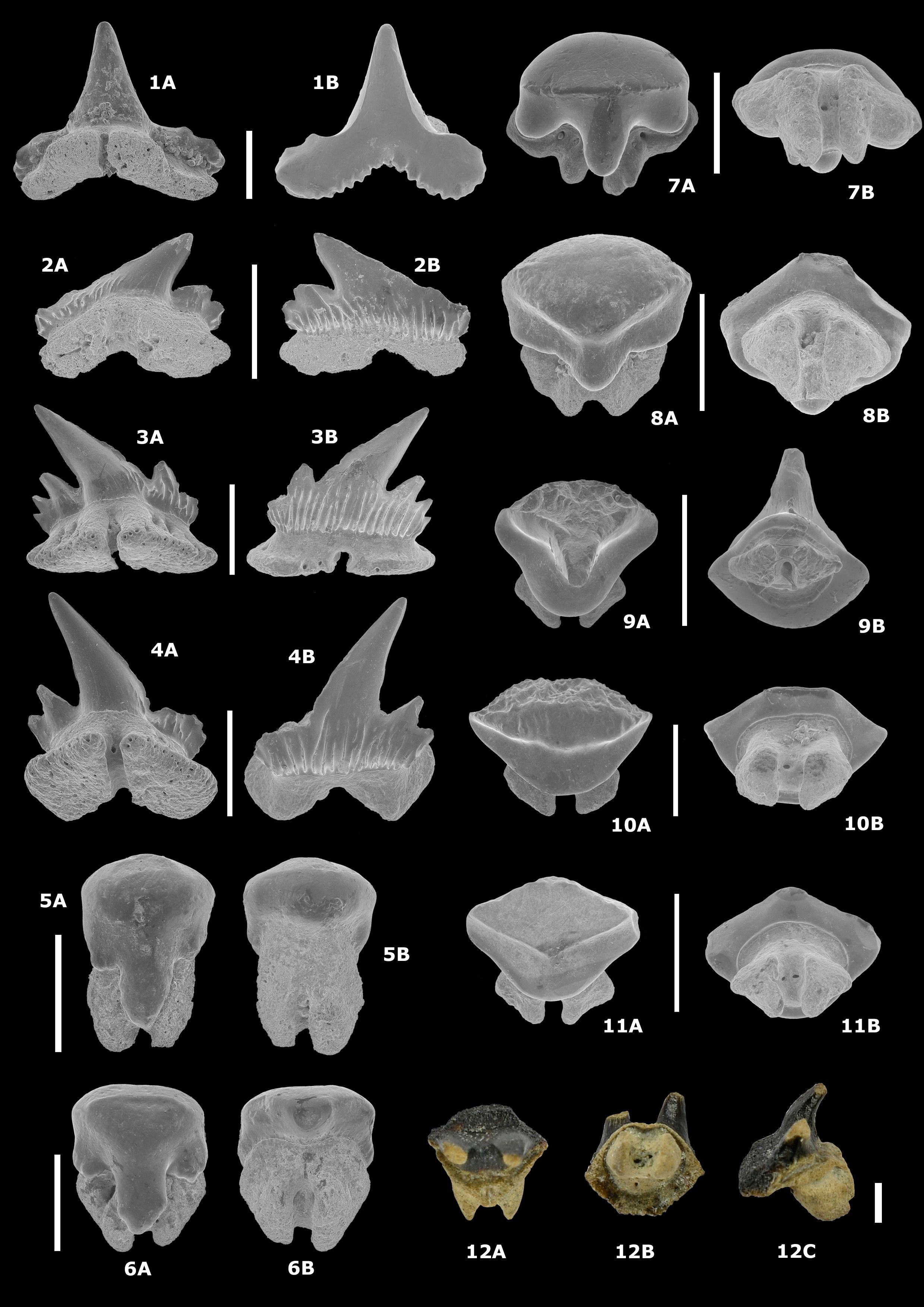

29(Pl. 2.2–4)

30Three teeth, IRSNB P 10779–10781, are confidently assigned to Pachyscyllium gilberti (Casier, 1946) (e.g. Cappetta & Nolf, 1981) because of the presence of a tall and sharp cusp, two pairs of well-developed cusplets (even a third marginal distal cusplet on one specimen) and vertical folds on the labial crown base and at the height of the cusplets on the lingual side. This species, which previously has been allocated to the genus Premontreia (e.g. Noubhani & Cappetta, 1997; Cappetta, 2006), was transferred to the genus Pachyscyllium (Cappetta, 2012, p. 267), mainly because of differences in root morphology.

31Foumtizia sp.

32(Pl. 2.1)

33One well preserved tooth (IRSNB P 10782) and two incomplete teeth can be attributed to the genus Foumtizia. The single complete specimen recovered from Papenboskant is mesio-distally elongated and measures 3 mm in width. It has a tall, erect but basally broad cusp, flanked by two pairs of low, rudimentary lateral cusplets, well separated from the main cusp. The crown’s cutting edge is complete, extending across the lateral cusplets. The labial crown base possesses coarse vertical folds on a prominent horizontal crest overhanging the root. The ornamentation does not extend to the crown face. The lingual crown face is equally smooth. The size of this specimen is fairly large for the genus, and markedly larger than the specimens of Foumtizia pattersoni (Cappetta, 1976) from the Ypresian of Egem (De Schutter, pers. obs.). This single well-preserved specimen is left in open nomenclature because the available material is insufficient for a confident species assignment, and certainly inappropriate for the formal erection of a new species.

4.3. Order Lamniformes

34Striatolamia macrota (Agassiz, 1843)

35(Pl. 1.2)

36A single (juvenile) tooth, IRSNB P 10783, is assigned to Striatolamia macrota (Agassiz, 1843) by the typical strong folds on the lingual crown surface. This shark is easily the most common larger species recorded in Eocene strata worldwide (e.g. Cappetta, 2012).

37Jaekelotodus trigonalis (Jaekel, 1895)

38(Pl. 1.1)

39A single tooth, IRSNB P 10784, is attributed to Jaekelotodus trigonalis (Jaekel, 1895). Its dentition consists of three upper anterior teeth followed by at least a single file of intermediate teeth, identical to that of its ancestor Jaekelotodus robustus (Leriche, 1921). The single J. trigonalis tooth recorded in the Asse Clay Member corresponds to an upper intermediate tooth position. This species is permanently occurring in the elasmobranch assemblages of the later part of the Eocene (e.g. Ward, 1980; Zhelezko & Kozlov, 1999; Trif et al., 2019, fig. 6 as Jaekelotodus robustus). Jaekelotodus robustus, which is still present in the Wemmel Sand Member (Leriche, 1905, 1921; Casier, 1966), seems to have disappeared in the overlying Asse Clay Member. Its successor, J. trigonalis occurs throughout both members.

4.4. Order Squaliformes

40Squalus minor (Daimeries, 1888)

41(Pl. 1.10)

42Two teeth, including IRSNB P 10785, correspond well with the type specimens of Squalus minor (Daimeries, 1888), figured in Leriche (1902) and originating from the Selandian Orp Sand Member (Heers Formation). According to Migom et al. (2021), this species is identical to Squalus smithi Herman, 1982a and a senior synonym of the latter. However, teeth of extant species of Squalus are very difficult to differentiate, even when complete sets are available. This demonstrates the difficulty in identifying fossil species, when only isolated teeth are available (Cappetta et al., 2016; Engelbrecht et al., 2017).

43Isistius trituratus (Winkler, 1874b)

44(Pl. 1.8)

45One complete tooth, IRSNB P 10786, and two incomplete teeth are attributed to Isistius trituratus (Winkler, 1874b), a species occurring throughout the entire Lutetian. It has been reported from the Brussel Sand Formation and Lede Sand Formation (e.g. Leriche, 1905; Van Den Eeckhaut & De Schutter, 2009; Hovestadt & Steurbaut, 2023) and, according to the present data, persists into the base of the Asse Clay Member. Isistius trituratus is common in the sand-dominated sediments of the Ypresian Mons-en-Pévèle Sand Formation (De Schutter, pers. obs.) and in the outer neritic London Clay Formation (Casier, 1966; Rayner et al., 2009), but seems to be very rare in the nearshore slightly younger Ypresian deposits from Egem (one specimen recorded to date, found in bed IV at the base of the Egemkapel Clay Member sensu Steurbaut, 1998, fig. 11) (Migom et al., 2021, p. 20) (Fig. 1).

4.5. Order Squatiniformes

46Squatina cf. prima (Winkler, 1874a)

47(Pl. 1.11)

48Eocene angel shark teeth have usually been assigned to Squatina prima (Winkler, 1874a), which type specimens came from the Selandian Orp Sand Member (Heers Formation) (e.g. Winkler, 1874a; Leriche, 1905, 1906; Casier, 1946, 1966; Nolf, 1988). Squatina crassa Daimeries, 1889, described from Ypresian and Lutetian strata, has smaller sized teeth than S. prima, and are more robust with a thick root. The single specimen in our sample, IRSNB P 10787, has a very slender and fragile morphology, leaning much more towards S. prima than S. crassa. However, as Squatinids present a very conservative (tooth) morphology and the taxonomy of extinct Squatinids is very problematic (e.g. Cappetta, 2012; Mollen et al., 2016), our specimen from Papenboskant is left in open nomenclature.

4.6. Order Rhinopristiformes

49‘Pseudobatos’ steurbauti (Cappetta & Nolf, 1981)

50(Pl. 2.5–6)

51These rhinobatoid teeth are easily recognisable by their small size, reaching a maximum height of 1 to 2 mm and by the presence of a globular crown with a well-developed central uvula. The anterior teeth possess barely marked lateral uvulae and their height is greater than their width. The two well-preserved teeth from the Asse Clay Member, IRSNB P 10788–10789, are similar to those of the upper Lutetian (Zone NP16) Sables d’Auvers in the Paris Basin, originally described as Rhinobatos steurbauti Cappetta & Nolf, 1981. They are also identical to the Ypresian teeth recently described from the Egem and Marke quarries, tentatively denoted as ‘Pseudobatos’ steurbauti (Cappetta & Nolf, 1981) (Reinecke et al., 2024). The Papenboskant find is only the second published record of the species in Belgium.

52‘Rhynchobatus’ vincenti Jaekel, 1894

53(Pl. 2.8)

54Six rhinid teeth, including IRSNB P 10790, are assigned to ‘Rhynchobatus’ vincenti Jaekel, 1894 because of their extreme width, which may exceed 3 mm and by the typical characteristics of the crown. The latter presents a large central uvula, but lacks lateral uvulae. Some irregular pitting occurs around the edges of the crown, which has a slightly globular or, when worn, flattened apical part.

55Glaucopristis bruxelliensis (Jaekel, 1894)

56(Pl. 2.7)

57Three complete teeth, including IRSNB P 10791, and ten incomplete specimens are attributed to Glaucopristis bruxelliensis (Jaekel, 1894). These teeth measure around 2 mm in height. They are smaller sized than those of ‘Rhynchobatus’ vincenti and often wider than high. They are furthermore characterised by a thick, rather long, central uvula and prominent, laterally diverging, lateral uvulae. Rhinobatos bruxelliensis Jaekel, 1894 was transferred to the recently created genus Glaucopristis (Reinecke et al., 2024). It is by far the most common rhinopristiform species in the Ypresian and Lutetian of Belgium (e.g. Leriche, 1905; Casier, 1946; Smith et al., 1999; Van Den Eeckhaut & De Schutter, 2009; Iserbyt & De Schutter, 2012).

4.7. Order Myliobatiformes

58Casierabatis spp.

59(Pl. 2.9–12)

60Reinecke et al. (2024) recently erected the genus Casierabatis to accommodate teeth of Casierabatis lambrechtsi Reinecke et al., 2024 from the Belgian Ypresian and those previously attributed to Dasyatis jaekeli (Leriche, 1905), originally described from the Lutetian (Hovestadt & Steurbaut, 2023, p. 94). Teeth of C. lambrechtsi have a labial crown surface covered with small and larger depressions and a very small secondary pitting. To the contrary, teeth of C. jaekeli lack the secondary pitting, and only possess a finely scarred surface with some irregular short folds and shallow pits. For an extensive description and iconography of both species the reader is referred to Reinecke et al. (2024).

61Sixteen specimens from the Asse Clay Member, including IRSNB P 10792–10795, present dental morphologies which match the general characteristics of Casierabatis, but cannot be reliably assigned to the two nominal species known to date and miss the necessary characteristics to serve as references for new species. Therefore, they are kept in open nomenclature and denoted as Casierabatis spp. Most of them (e.g. IRSNB P 10792–10793, Pl. 2.9–10) present a coarser labial crown ornamentation than that observed in C. lambrechtsi and miss the small-scaled secondary pitting typical of this species, but at the same time, do not show the finely scarred surface of C. jaekeli. These specimens are provisionally left in open nomenclature, because it is still unclear whether these differences fall within the intraspecific variability of the nominal Casierabatis species or if they justify the erection of a new taxon or not. One specimen (IRSNB P 10794, Pl. 2.11) has a flat, strongly abraded crown and is too poorly preserved to allow an identification to species level. One specimen (IRSNB P 10795, Pl. 2.12) is fairly atypical for the genus Casierabatis, being very large, measuring 3.5 mm in height, and having a split crown. Such teeth with a split crown are considered pathological (Reinecke et al., 2024, p. 72) and cannot be designated as a reference for a new species, new genus or some other taxon. Hence, this aberrant tooth from the Asse Clay Member is also left in open nomenclature.

62‘Myliobatis’ sp.

63(Pl. 1.4)

64Batoid dental plates, similar to IRSNB P 10796, have traditionally been identified as Myliobatis dixoni (Agassiz, 1843). Cappetta (2012), based on the labial and lingual crown ornamentation, suggested an affiliation with the extant genus Aetomylaeus Garman, 1908. However, Hovestadt & Hovestadt-Euler (2013) and Reinecke et al. (2024) noted the high variability within the dentition of extant Myliobatid species and the extreme difficulty of confidently identifying isolated fossil myliobatid teeth. This partial dental plate, IRSNB P 10796, and five isolated lateral teeth are, therefore, denoted as ‘Myliobatis’ sp. A major revision of the entire family is needed to resolve the problem.

5. First record of Notorynchus kempi Ward, 1979 in Belgium

65A single tooth of Notorynchus (IRSNB P 650), originating from the Wemmel Sand Member and figured by Leriche (1905, p. 207, text-fig. 62) as Notidanus primigenius Agassiz, 1843, was re-examined and refigured herein (Fig. 4). This specimen (IRSNB P 650), collected in the 19th century at Neder-Over-Heembeek (Fig. 2), represents the first published record of Notorynchus kempi Ward, 1979 in Belgium.

66Although the identification of Notorynchus species is primarily based on isolated lower antero-lateral teeth, and on somehow variable and rather subjective dental characters (Bor et al., 2012), the single upper antero-lateral tooth available, can be attributed to N. kempi by its large size (17.9 mm wide), fine mesial cusplets and curved, distally directed, distal cusplets. This species was originally described from the Bartonian of England (Highcliffe Member, NP 17, see King, 2016). Our specimen differs from the early and middle Eocene teeth of N. serratissimus (Agassiz, 1843) by its larger size, by an apico-basally deeper root with a larger lingual protuberance and by finer and evenly sized mesial cusplets on the principal cusp. The principal cusp and the three distal cusplets are all distally oriented. In addition, the distal cusplets diminish in size away from the principal cusp (Ward, 1979). The Oligocene–Miocene N. primigenius (Agassiz, 1843) has larger teeth, especially in the Oligocene (e.g. Leriche, 1910), and coarser mesial cusplets. The principal cusp and distal cusplets are relatively larger and more robust, more pointed and less distally directed (Ward, 1979).

Figure 4. An upper antero-lateral tooth of Notorynchus kempi Ward, 1979 (IRSNB P 650) collected from the Wemmel Sand Member at Neder-over-Heembeek, district of Brussels. Lingual (A) and labial (B) views. Scale bar = 5 mm.

6. Palaeobiodiversity and palaeoenvironmental considerations

6.1. Composition of the elasmobranch fauna of the Maldegem Formation

67The elasmobranch fauna of the Maldegem Formation currently consists of 26 taxa. It is exclusively originating from the Wemmel Sand Member and the base of the Asse Clay Member (traditionally known as the bande noire) and includes the historical collections studied by Leriche (1905,1906), additional material listed by Casier (1966) and the material collected by J. Herman at Papenboskant in 1998, first studied herein. The identified taxa are summarized in Table 2, taking into account the taxonomic updates commented on in Section 4.

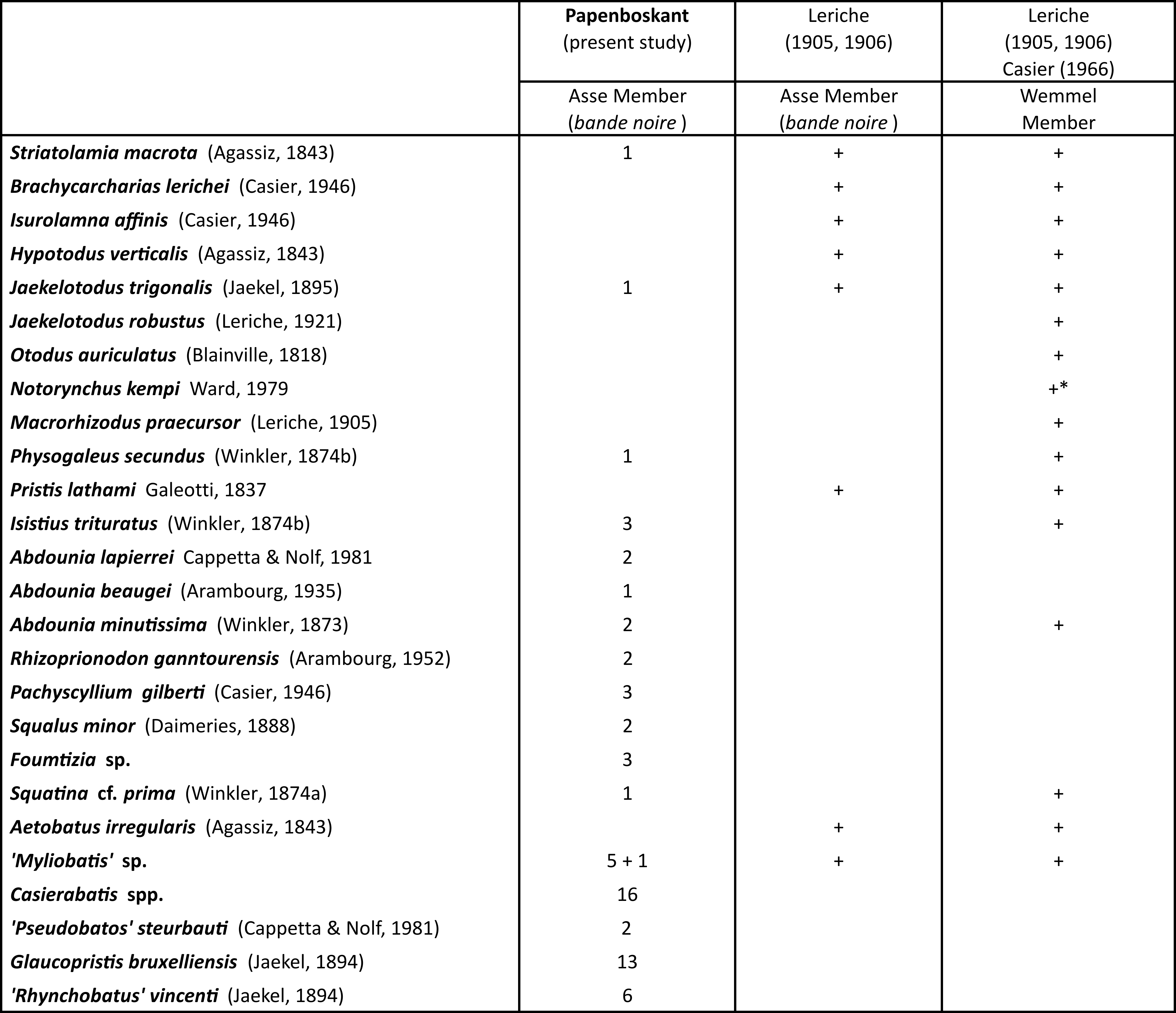

Table 2. Overview of the Elasmobranch assemblages from the Wemmel Sand Member and the base of the Asse Clay Member (lower part of the Maldegem Formation, middle Lutetian), based on Leriche (1905, 1906), Casier (1966) and the present paper (* see Section 5).

68The faunal assemblage of the Wemmel Sand Member yields 16 taxa, 11 of which were listed by Leriche (1905, 1906) and 5 were subsequently added by Casier in his monograph on the London Clay (1966, p. 273, table IV), although without any descriptions or figures. Five additional species (Eostegostoma angustum (Nolf & Taverne) in Herman, 1977; Nebrius thielensi (Winkler, 1873); Palaeorhincodon wardi Herman, 1975; Archaeomanta melenhorsti Herman, 1979; and Mustelus sp.) were described by Herman (1977, 1979, 1982b) from the base of the Wemmel Sand Member at Schepdaal. At the time of sampling in 1976, Herman, noting the exceptional preservation of the teeth and lacking awareness of comparable Ypresian faunas, considered the assemblage to be autochthonous. Subsequent study, however, led him to correctly interpret the material as reworked from underlying Lutetian and Ypresian strata (Herman, 2010, personal notes, file 87E8” of the Belgian Geological Survey). Consequently, this material is not included in Table 2.

69Twenty-two taxa are recorded from the base of the Asse Clay Member, 17 of which from the Papenboskant locality. Eight of these 22 taxa were already known by Leriche (1905, 1906) and 14 are listed here for the first time, among which the first published record of Abdounia lapierrei in Belgium (Table 2). All taxa from the base of the Asse Clay Member reported by Leriche have been recorded in the historical collections of the Wemmel Sand Member.

70The number of taxa in both the Wemmel Sand Member and the base of the Asse Clay Member is too limited for far-reaching conclusions. However, there are differences between the material taken from the base of the Asse Clay Member at Papenboskant and that from the historical collections from the Wemmel Sand and Asse Clay members. Taxa with small teeth (maximum tooth length <5 mm) are under-represented or nearly absent in the historical ‘Leriche – Casier’ material, which contains only one (Squatina cf. prima) of the nine small-toothed taxa recorded at Papenboskant. This discrepancy is essentially due to differences in sampling methodology. At Papenboskant, a 0.5 mm mesh sieve was used, allowing the recovery of very small specimens (74% of the total number of teeth are less than 5 mm long), whereas the material from historical collections was largely handpicked, favouring the collection of larger teeth. Interestingly, most taxa recovered from the Wemmel Sand Member, which are predominantly large-toothed taxa (main tooth length >1 cm), such as Hypotodus verticalis (Agassiz, 1843), Isurolamna affinis (Casier, 1946), Otodus auriculatus (Blainville, 1818) and others, are absent from the Papenboskant assemblage. This probably reflects the rarity of elasmobranch remains in the lower members of the Maldegem Formation (less than one specimen per 20 kg sediment at Papenboskant) where the recovery of each additional taxon requires the processing of a tremendous amount of sediment.

6.2. Taphonomic, palaeoenvironmental and palaeobiogeographic results

71The elasmobranch assemblage from Papenboskant exclusively consist of isolated teeth of benthic and neritic taxa, which apparently accumulated on the seafloor as the result of normal physiologic processes, essentially tooth shed. The presence of not fully grown shark teeth, however, shows that at least one, and probably more, dead animals contributed to the formation of this assemblage. The natural mix of small-sized and large-sized teeth, similar to the size distribution in the other fossil invertebrate groups (unpublished data by Herman, commented on in the Supplementary material), seems to exclude strong selective sediment transport and sorting, suggesting feeble wave action and little or no lateral displacement. This suggests that the bande noire at this locality is not a beach deposit, but formed slightly deeper, along the lower shoreface, just below fair-weather wave base. The reduced sand fraction, as well as the abundance of glauconite, much of which is coarse-grained, and the abundance of nummulites, corroborate with this depositional model, as medium- to coarse-grained glauconite and nummulites proliferate in areas with low sediment supply and few or no turbulence, conditions which are met with on the lower shoreface.

72Members of the families Pristidae, Myliobatidae, Dasyatidae, and small Carcharhiniformes, are well represented in the assemblage and are all indicative of tropical and warm-temperature areas with a preference for shallow waters (Compagno, 1984, 2001; Carpenter & Niem, 1999). The majority of the batoids of the assemblage belong to the myliobatiform Casierabatis, abundantly present in the inner neritic deposits at Egem, confirming their preference for shallow marine habitats (Reinecke et al., 2024). This also applies to ‘Pseudobatos’ steurbauti (Cappetta & Nolf, 1981), which is absent in the outer neritic London Clay Formation, but common at Egem (Reinecke et al., 2024). Most Myliobatiformes are also benthic predators that evolved a flattened morphology allowing them to cover themselves in soft-bottom environments (Ferry-Graham et al., 2002). Similarly, extant Squatina are often found hiding in muddy or sandy bottoms, feeding on a variety of small invertebrates and small bony fish, caught by ambush attack (e.g. Compagno, 1984; Mollen et al., 2016). Smaller shallow-water predatory sharks, represented by Physogaleus, Abdounia and Rhizoprionodon, are presumably somewhat generalist feeders on small active prey such as bony fishes (Underwood et al., 2011). As is typical for Eocene selachian assemblages, multiple species of the genus Abdounia (Cappetta, 1980) coexisted. Additionally, the presence of large open-water predators like Jaekelotodus, and some pelagic Squalidae and Dalatiidae, indicate a connection with the Atlantic Ocean. Supporting this view is Isistius, a tropical oceanic shark characterised by highly specialised foraging tactics and the necessity to migrate to greater depths during daytime (Papastamatiou et al., 2010). Squalus also needs to retreat into deeper water to stay within their optimal temperature range (Compagno, 1984).

73The Elasmobranch fauna of the lower part of the Maldegem Formation has many species in common with the fauna of the Sables d’Auvers in the Paris Basin (75% of the taxa in these sands are recorded at Papenboskant; Cappetta & Nolf, 1981) and with the fauna of the Selsey Formation in the Hampshire Basin (especially the many in common subtropical to warm-temperate large open water and oceanic taxa, such as Jaekelotodus trigonalis (Jaekel, 1895), Isistius trituratus (Winkler, 1874b), Macrorhizodus praecursor (Leriche, 1905), Notorynchus kempi Ward, 1979 and Otodus auriculatus (Blainville, 1818) (Kemp et al., 1990; Ward, 2016). This suggests that during the middle and late Lutetian (Biochron late NP15 to Biochron early NP16) these three subareas of the southern North Sea were still interconnected and opened to the Atlantic Ocean, not only through the north but also via the English Channel to the southwest.

6.3. Biostratigraphic remarks

74A close inspection of existing literature data reveals that most of the recorded taxa from the Papenboskant section are fairly common in middle Ypresian to upper Lutetian–lower Bartonian deposits of the North Sea Basin (e.g. Casier, 1946, 1966; Cappetta, 1976; Ward, 1980; Nolf, 1988; Smith et al., 1999; Cappetta & Nolf, 2005; Van Den Eeckhaut & De Schutter, 2009; Ward, 2016). Some of these existed over a very long period of time, dating back to the middle Paleocene (e.g. Smith et al., 1999, table III), while others (e.g. Striatolamia macrota (Agassiz, 1843), Jaekelotodus trigonalis (Jaekel, 1895), Isistius trituratus (Winkler, 1874b), etc.) persisted up in the earliest Bartonian (Ward, 2016). Abdounia lapierrei Cappetta & Nolf, 1981, which in Belgium is only known from the middle Lutetian Asse Clay Member, appears to be restricted to the Lutetian. It has been reported from the lower Lutetian Earnley Formation up to the uppermost Lutetian–basal Bartonian Elmore Member in the Hampshire Basin (Kemp et al., 1990; Ward, 2016) and from the upper Lutetian Sables d’Auvers in the Paris Basin (Cappetta & Nolf, 1981). Some representatives of the Casierabatis species group may also have biostratigraphic relevance, although this still needs further confirmation.

7. Conclusions

75The stratigraphic investigation and bulk sediment sampling of the bande noire at the base of the Asse Clay Member at Papenboskant (Wolvertem), 20 km north of Brussels, led to the following conclusions:

761. The Papenboskant excavation resulted in the discovery of the richest and most diversified invertebrate fauna ever recovered from the bande noire horizon and from the Asse Clay Member tout court. This is also true for the elasmobranch fauna studied herein, which consists of 22 taxa, 14 of which have never been recorded from this middle Lutetian horizon before.

772. The elasmobranch fauna of the bande noire horizon is dominated by benthic batoid taxa, several of which prefer hiding in the soft fine-grained sea bottom sediment. It also includes several neritic tropical to warm-temperate small predatory sharks, essentially feeding on small bony fish, and some large open-water predators and pelagic taxa. Some of the open-water taxa undertake daily migrations to deeper waters, like Isistius, the sole oceanic taxon recorded.

783. The elasmobranch data reveal that, during middle Lutetian times, the area north of Brussels was covered by a tropical to warm-temperate shallow sea, with sandy to muddy bottoms and an open connection to deeper waters. The palaeontological and sedimentological context suggests that sedimentation took place along the lower shoreface, just below main wave base, in an area with very low sediment supply, initiating the formation and accumulation of coarse-grained glauconite, fossil shell beds and nummulite-rich layers.

794. The strong similarities between the elasmobranch assemblages of the Belgian, Hampshire and Paris basins suggest that during the middle and late Lutetian, these three subareas of the southern North Sea were still interconnected and opened to the Atlantic Ocean, not only through the north but also via the southwestern English Channel.

805. Virtually all of the recovered elasmobranch taxa existed over a considerable period of time and were reported from other Ypresian and/or Lutetian deposits across the North Sea Basin. Abdounia lapierrei Cappetta & Nolf, 1981 appears to possess biostratigraphic significance, being so far restricted to Lutetian strata. Certain representatives of the Casierabatis species group may likewise be limited to the basal part of the Asse Clay Member, pending confirmation.

816. The re-examination of Leriche’s historical museum collections, which was carried out within the scope of the present paper, revealed that the single tooth of Notorynchus recovered from the Wemmel Sand Member (Leriche, 1905) represents the first occurrence of Notorynchus kempi in Belgium.

827. This study highlights the need for caution when interpreting historical elasmobranch museum collections, as they were largely handpicked and under-represent small-toothed taxa that dominate recent sieved assemblages.

Acknowledgements

83The authors wish to express their gratitude to the Palaeontological Collection Service of the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences (Brussels) for providing access to its extensive elasmobranch collection. They are also grateful to Taco Bor, Jean-Marie Canevet, Jef Deckers and Thomas Reinecke, for sharing their valuable thoughts, increasing the quality of this work. Gunther Cleemput is thanked for his technical support and Jürgen Pollerspöck and the “Shark-references” web-project (Pollerspöck & Straube, 2024) for easy access to their exhaustive list of references on fossil chondrichthyans. We are also indebted to Noël Vandenberghe and David Ward for the critical reading of the manuscript and helpful suggestions.

Author contribution

84PDS performed the taxonomic analysis of the elasmobranch material, collected by Jacques Herman in 1998, and designed the figures and plates. PDS and ES wrote the manuscript.

Data availability

85All studied specimens are housed in official repositories guaranteeing their long-term safekeeping and availability to other researchers for future studies.

References

86Adolfssen, J.S. & Ward, D.J., 2015. Neoselachians from the Danian (early Paleocene) of Denmark. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica, 60/2, 313–338. http://dx.doi.org/10.4202/app.2012.0123

87Bengtson, P., 1988. Open Nomenclature. Palaeontology, 31/1, 223–227.

88Bor, T., Verschuere, S. & Reinecke, T., 2012. Miocene Chondrichthyes from Winterswijk-Miste, the Netherlands. Palaeontos, 21, 1–136.

89Burtin, F.-X., 1784. Oryctographie de Bruxelles ou description des fossiles tant naturels qu’accidentels découverts jusqu’à ce jour dans les environs de cette ville. L’Imprimerie de le Maire, Bruxelles, 152 p. https://doi.org/10.5962/bhl.title.145344

90Cappetta, H., 1976. Sélaciens nouveaux du London Clay de l’Essex (Yprésien du Bassin de Londres). Geobios, 9/5, 551–575. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-6995(76)80024-1

91Cappetta, H., 1980. Modification du statut générique de quelques espèces de sélaciens crétacés et tertiaires. Palaeovertebrata, 10, 29–42.

92Cappetta, H., 2006. Elasmobranchii Post-Triadici (index specierum et generum). In Riegraf, W. (ed.), Fossilium Catalogus I, Animalia pars 142. Leiden, Backhuys Publishers, 472 p.

93Cappetta, H., 2012. Chondrichthyes. Mesozoic and Cenozoic Elasmobranchii: Teeth. In Schultze, H.P. (ed.), Handbook of Paleoichthyology, 3E. Verlag Dr. Friedrich Pfeil, München, 512 p.

94Cappetta, H. & Nolf, D., 1981. Les sélaciens de l’Auversien de Ronquerolles (Eocène supérieur du Bassin de Paris). Mededelingen van de Werkgroep voor Tertiaire en Kwartaire Geologie, 18/3, 87–107.

95Cappetta, H. & Nolf, D., 2005. Révision de quelques Odontaspididae (Neoselachii: Lamniformes) du Paléocène et de l’Eocène du Bassin de la mer du Nord. Bulletin de l’Institut royal des Sciences naturelles de Belgique, Sciences de la Terre, 75, 237–266.

96Cappetta, H., Gregorová, R. & Adnet, S., 2016. New selachian assemblages from the Oligocene of Moravia (Czech Republic). Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie, Abhandlungen, 280/3, 259–284. https://doi.org/10.1127/njgpa/2016/0579

97Carpenter, K.E. & Niem, V.H. (eds), 1999. The Living Marine Resources of the Western Central Pacific. Volume 3: Batoid fishes, chimaeras and bony fishes part 1 (Elopidae to Linophrynidae). FAO species identification guide for fishery purposes. Rome, FAO, 1397–2068.

98Casier, E., 1946. La faune ichthyologique de l’Yprésien de la Belgique. Mémoires du Musée royal d’Histoire naturelle de Belgique, 104, 267 p.

99Casier, E., 1949. Contributions à l’étude des poissons fossiles de la Belgique. VIII. Les Pristidés éocènes. Bulletin de l’Institut royal des Sciences naturelles de Belgique, 25/10, 52 p.

100Casier, E., 1950. Contributions à l’étude des poissons fossiles de la Belgique. IX. La faune des formations dites “Paniséliennes”. Bulletin de l’Institut royal des Sciences naturelles de Belgique/Mededelingen van het Koninklijk Belgisch Instituut voor Natuurwetenschappen, 26/42, 53 p.

101Casier, E., 1966. Faune ichthyologique du London Clay. Trustees of the British Museum (Natural History), London, 496 p.

102Cohen, K.M., Finney, S.C., Gibbard, P.L. & Fan, J.-X., 2024. The ICS International Chronostratigraphic Chart, v. 2024/12. Update of 2013. Episodes, 36, 199–204. https://stratigraphy.org/ICSchart/ChronostratChart2024-12.pdf

103Compagno, L.J.V., 1984. FAO Species Catalogue. Vol. 4. Sharks of the world. An annotated and illustrated catalogue of shark species known to date. Part 1. Hexanchiformes to Lamniformes. FAO, Rome, FAO Fisheries Synopsis, 125, 249 p.

104Compagno, L.J.V., 2001. Sharks of the World. An annotated and illustrated catalogue of shark species known to date. Vol. 2. Bullhead, mackerel and carpet sharks (Heterodontiformes, Lamniformes and Orectolobiformes). FAO, Rome, FAO Species Catalogue for Fishery Purposes, 1, 269 p.

105[Conseil géologique], 1929. Légende générale de la Carte géologique détaillée de la Belgique. Annales des Mines de Belgique, 30/1, 39–80.

106Cunningham, S., 2000. A comparison of isolated teeth of early Eocene Striatolamia macrota (Chondrichthyes, Lamniformes), with those of a Recent sand shark, Carcharias taurus. Tertiary Research, 20/1-4, 17–31.

107De Coninck J., 1995. Corrélations entre les dépôts du Lutétien au Rupélien du Bassin belge, et des Bassins de Hamsphire et de Paris. Mededelingen Rijks Geologische Dienst, 53, 107–118.

108Delvaux, E, 1886. Visite aux gites fossilifères d’Aeltre et exploration des travaux en cours d’exécution à la colline de Saint-Pierre à Gand. Annales de la Société royale malacologique de Belgique, 21, 274–296.

109de Meijer, P., 1973a. Haaietanden en andere fossielen uit de transgressielaag aan de basis van het Ledien bij Aalst. Gea, 6/1, 31–37.

110de Meijer, P., 1973b. Haaietanden en andere fossielen uit de transgressielaag aan de basis van het Ledien bij Aalst. Gea 6/2, 51–53.

111Dupuis, C., De Coninck, J. & Steurbaut, E. (eds), 1991. The Ypresian stratotype. Bulletin de la Société belge de Géologie/Bulletin van de Belgische Vereniging voor Geologie, 97/3-4 (pro 1988), 225–479.

112Ebersole, J.A., Cicimurri, D.J. & Stringer, G.L., 2019. Taxonomy and biostratigraphy of the elasmobranchs and bony fishes (Chondrichthyes and Osteichthyes) of the lower-to-middle Eocene (Ypresian to Bartonian) Claiborne Group in Alabama, USA, including an analysis of otoliths. European Journal of Taxonomy, 585, 1–274. https://doi.org/10.5852/ejt.2019.585

113Ebersole, J.A., Kelosky, A.T., Huerta-Beltrán, B.L., Cicimurri, D.J. & Drymon, J.M., 2023. Observations on heterodonty within the dentition of the Atlantic Sharpnose Shark, Rhizoprionodon terraenovae (Richardson, 1836), from the north-central Gulf of Mexico, USA, with implications on the fossil record. PeerJ, 11, e15142. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.15142

114Ebersole, J.A., Cicimurri, D.J. & Harrell, L., 2024. A new species of Palaeohypotodus Glückman, 1964 (Chondrichthyes, Lamniformes) from the lower Paleocene (Danian) Porters Creek Formation, Wilcox County, Alabama, USA. Fossil Record, 27/1, 111–134. https://doi.org/10.3897/fr.27.112800

115Engelbrecht, A., Mörs, T., Reguero, M.A. & Kriwet, J., 2017. Eocene squalomorph sharks (Chondrichthyes, Elasmobranchii) from Antarctica. Journal of South American Earth Sciences, 78, 175–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsames.2017.07.006

116Ferry-Graham, L.A., Bolnick, D.I. & Wainwright, P.C., 2002. Using functional morphology to examine the ecology and evolution of specialization. Integrative and Comparative Biology, 42, 265–277. https://doi.org/10.1093/icb/42.2.265

117Glibert, M., 1936. Faune malacologique des Sables de Wemmel. I. Pélécypodes. Mémoires du Musée royal d’histoire naturelle de Belgique, 78, 1–242.

118Glibert, M., 1938. Faune malacologique des Sables de Wemmel. II. Gastropodes, Scaphopodes, Céphalopodes. Mémoires du Musée royal d’histoire naturelle de Belgique, 85, 1–191.

119Glückman, L.S., 1964. [Sharks of the Paleogene and their Stratigraphic Significance]. Nauka Press, Moscow, 229 p. [In Russian].

120Hacquaert, A., 1936. Compte rendu de l’excursion du 28 mai 1936 aux chantiers des nouveaux bâtiments universitaires, à Gand. Bulletin de la Société belge de Géologie, Paléontologie et d’Hydrologie, 46, 273–276.

121Herman, J., 1975. Compléments palaeoichtyologiques à la faune éocène de la Belgique. 1. Palaeorhincodon, genre nouveau de l’Eocène belge. Bulletin de la Société belge de Géologie, 83/1 (pro 1974), 7–13.

122Herman, J. (with Crochard, M.), 1977. Additions to the Eocene fish fauna of Belgium. 3. Revision of the Orectolobiforms. Tertiary Research, 1/4, 127–138.

123Herman, J. (with Crochard, M.), 1979. Additions to the Eocene fish fauna of Belgium. 4. Archaeomanta, a new genus from the Belgian and North African Palaeogene. Tertiary Research, 2/2, 61–67.

124Herman, J., 1982a. Additions to the fauna of Belgium. 6. The Belgian Eocene Squalidae. Tertiary Research, 4/1, 1–6.

125Herman, J., 1982b. Additions to the Eocene fish fauna of Belgium. 5. The discovery of Mustelus teeth in Ypresian, Paniselian and Wemmelian strata. Tertiary Research, 3/4, 189–193.

126Herman, J., 1984. Additions to the Eocene (and Oligocene) fauna of Belgium. 7. Discovery of Gymnura teeth in Ypresian, Paniselian and Rupelian strata. Tertiary Research, 6/2, 47–54.

127Herman, J., 1986. Additions to the Eocene fish fauna of Belgium. 8. A new rajiform from the Ypresian-Paniselian. Tertiary Research, 8, 33–42.

128Hovestadt, D.C. & Hovestadt-Euler, M., 2013. Generic assessment and reallocation of Cenozoic Myliobatins based on new information of tooth, tooth plate and caudal spine morphology of extant taxa. Palaeontos, 24, 1–66.

129Hovestadt, D. & Steurbaut, E., 2023. Annotated iconography of the type specimens of fossil chondrichthyan fishes in the collection of the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences, Brussels. Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences, Brussels, Monographs in Natural Sciences, 1, 122 p.

130Iserbyt, A. & De Schutter, P.J., 2012. Quantitative analysis of Elasmobranch assemblages from two successive Ypresian (early Eocene) facies at Marke, western Belgium. Geologica Belgica, 15/3, 146–153.

131Jacobs, P., 1978. Litostratigrafie van het Boven-Eoceen en van het Onder-Oligoceen in Noordwest België. Belgische Geologische Dienst, Professional Papers, 1978/3, 151, 92 p.

132Jacobs, P. & Sevens, E., 1993. Eocene siliciclastic continental shelf sedimentation in the Southern Bight North Sea, Belgium. In Progress in Belgian Oceanographic Research (Brussels, January 21-22, 1993). Royal Academy of Belgium, National Committee of Oceanology, Brussels, 95–118.

133Jacobs, P. & Sevens, E. 1994. Middle Eocene sequence stratigraphy in the Balegem quarry (Western Belgium, Southern Bight North Sea). Bulletin de la Société belge de Géologie/Bulletin van de Belgische Vereniging voor Geologie, 102 (pro 1993), 203–213.

134Kaasschieter, J., 1961. Foraminifera of the Eocene of Belgium. Mémoires du Musée royal d’Histoire naturelle de Belgique, 147, 1–271

135Kemp, D., Kemp, L. & Ward, D., 1990. An Illustrated Guide to the British Middle Eocene Vertebrates. Published by D. Ward, London, 59 p.

136Kent, B.W., 1999. Sharks from the Fisher/Sullivan Site. In Weems, R.E. & Grimsley, G.J. (eds), Early Eocene Vertebrates and Plants from the Fisher/Sullivan Site (Nanjemoy Formation) Stafford County, Virginia. Virginia Division of Mineral Resources, Publications, 152, 11–37.

137King, C., 2016. A Revised Correlation of Tertiary Rocks of the British Isles and Adjacent Areas of NW Europe. Geological Society, London, Special Reports, 27, 719 p. https://doi.org/10.1144/SR27

138Leriche, M., 1902. Les poissons paléocènes de la Belgique. Mémoires du Musée royal d’Histoire naturelle de Belgique, 2, 1–48.

139Leriche, M., 1905. Les poissons éocènes de la Belgique. Mémoires du Musée royal d’Histoire naturelle de Belgique, 3, 49–228.

140Leriche, M., 1906. Contribution à l’étude des poissons fossiles du Nord de la France et des régions voisines. Mémoires de la Société géologique du Nord, 5, 1–430.

141Leriche, M., 1910. Les poissons oligocènes de la Belgique. Mémoires du Musée royal d’Histoire naturelle de Belgique, 5, 231–363.

142Leriche, M., 1921. Sur les restes de poissons remaniés dans le Néogène de la Belgique. Leur signification au point de vue de l’histoire géologique de la Belgique pendant le Tertiaire supérieur. Bulletin de la Société belge de Géologie, de Paléontologie et d’Hydrologie, 30, 115–120.

143Leriche, M., 1939. Un gîte fossilifère dans le Bartonien du Meetjesland (Pays d’Eecloo) et sur le sens à donner au nom de Bartonien. Annales de la Société géologique de Belgique, 62, 552–559.

144Leriche, M., 1951. Les poissons tertiaires de la Belgique (supplément). Mémoires de l’Institut royal des Sciences naturelles de Belgique, 118, 473–600.

145Lyell, C., 1852. On the Tertiary strata of Belgium and French Flanders. Part II. The Lower Tertiaries of Belgium. Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London, 8/31, 277–370. https://doi.org/10.1144/GSL.JGS.1852.008.01-02.34

146Maréchal, R., 1994. A new lithostratigraphic scale for the Palaeogene of Belgium. Bulletin de la Société belge de Géologie, 102 (pro 1993), 215–229.

147Migom, F., Christiaens, Y. & Deceuckeleire, M., 2021. The Lower Eocene (Ypresian) Chondrichthyes from Egem, Belgium. Part 1, Orders: Hexanchiformes, Squaliformes, Squatiniformes, Heterodontiformes and Orectolobiformes. Palaeo Ichthyologica, 15, 1–55.

148Molina, E., Alegret, L., Apellaniz, E., Bernaola, G., Caballero, F., Dinarès-Turell, J., Hardenbol, J., Heilmann-Clausen, C., Larrasoaña, J.C., Luterbacher, H., Monechi, S., Ortiz, S., Orue-Etxebarria, X., Payros, A., Pujalte, V., Rodríguez-Tovar, F.J., Tori, F., Tosquella, J. & Uchman, A., 2011. The Global Standard Stratotype Section and Point (GSSP) for the base of the Lutetian Stage at the Gorrondatxe section, Spain. Episodes, 34/2, 86–108. https://doi.org/10.18814/epiiugs/2011/v34i2/006

149Mollen, F., 2008. A new Middle Eocene species of Premontreia (Elasmobranchii, Scyliorhinidae) from Vlaams-Brabant, Belgium. Geologica Belgica, 11, 123–131.

150Mollen, F.H., van Bakel, B.W.M. & Jagt, J.W.M., 2016. A partial braincase and other skeletal remains of Oligocene angel sharks (Chondrichthyes, Squatiniformes) from northwest Belgium, with comments on squatinoid taxonomy. Contributions to Zoology, 85/2, 147–171. https://doi.org/10.1163/18759866-08502002

151Nolf, D., 1972. Sur la faune ichthyologique des formations du Panisel et de Den Hoorn (Eocène belge). Bulletin de la Société belge de Géologie, de Paléontologie et d’Hydrologie, 81, 111–138.

152Nolf, D., 1973. Deuxième note sur les Téléostéens des Sables de Lede (Eocène belge). Bulletin de la Société belge de Géologie, de Paléontologie et d’Hydrologie, 81/1-2 (pro 1972), 95–109.

153Nolf, D., 1988. Fossielen van België. Haaie- en roggetanden uit het Tertiair van België. Koninklijk Belgisch Instituut voor Natuurwetenschappen, Brussel, 180 p.

154Noubhani, A. & Cappetta, H., 1997. Les Orectolobiformes, Carcharhiniformes et Myliobatiformes (Elasmobranchii, Neoselachii) des Bassins à phosphates du Maroc (Maastrichtien-Lutétien basal). Systématique, biostratigraphie, évolution et dynamique des faunes. Palaeo Ichthyologica, 8, 1–327.

155Papastamatiou, Y.P., Wetherbee, B.M., O’Sullivan, J., Goodmanlowe, G.D. & Lowe, C.G., 2010. Foraging ecology of Cookiecutter Sharks (Isistius brasiliensis) on pelagic fishes in Hawaii, inferred from prey bite wounds. Environmental Biology of Fishes, 88, 361–368. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10641-010-9649-2

156Pollerspöck, J. & Straube, N., 2024. Bibliography Database of Living/fossil Sharks, Rays and Chimaeras (Chondrichthyes: Elasmobranchii, Holocephali). Shark References.com. www.shark-references.com, accessed 18/01/2025.

157Rayner, D., Mitchell, T., Rayner, M. & Clouter, F., 2009. London Clay Fossils of Kent and Essex. Medway Fossil and Mineral Society, Rochester (Kent), 228 p.

158Reinecke, T., Mollen, F.H., Gijsen, B., D’haeze, B. & Hoedemakers, K. 2024. Batomorphs (Elasmobranchii: Rhinopristiformes, Rajiformes, Torpediniformes, Myliobatiformes) of the middle to late Ypresian, early Eocene, in the Anglo-Belgian Basin (south-western North Sea Basin) – a review and description of new taxa. Palaeontos, 35, 1–171.

159Smith, R., Smith, T. & Steurbaut, E., 1999. Les élasmobranches de la transition Paléocène-Eocène de Dormaal (Belgique) : implications biostratigraphiques et paléobiogéographiques. Bulletin de la Société géologique de France, 170, 327–334.

160Speijer, R.P., Pälike, H., Hollis, C.J., Hooker, J.J. & Ogg, J.G., 2020. The Paleogene period. In Gradstein, F.M., Ogg, J.G., Schmitz, M.D. & Ogg, G.M. (eds), Geologic Time Scale 2020. Elsevier, Amsterdam, 1087–1140. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-824360-2.00028-0

161Steurbaut, E., 1986. Late Middle Eocene to Middle Oligocene calcareous nannoplankton from the Kallo well, some boreholes and exposures in Belgium, and a description of the Ruisbroek Sand Member. Mededelingen van de Werkgroep voor Tertiaire en Kwartaire Geologie, 23/2, 49–83.

162Steurbaut, E., 1998. High-resolution holostratigraphy of Middle Paleocene to Early Eocene strata in Belgium and adjacent areas. Palaeontographica, Abt. A, 247, 91–156. https://doi.org/10.1127/pala/247/1998/91

163Steurbaut, E., 2006. Ypresian. In Dejonghe, L. (ed.), Current status of chronostratigraphic units named from Belgium and adjacent areas. Geologica Belgica, 9/1-2, 73–93.

164Steurbaut, E., 2015. Het vroeg-Eoceen. In Borremans, M. (ed.), Geologie van Vlaanderen. Academia Press, Gent, 125–135.

165Steurbaut, E. & King, C., 1994. Integrated stratigraphy of the Mont-Panisel borehole section (151E340), Ypresian (Early Eocene) of the Mons Basin, SW Belgium. Bulletin de la Société belge de Géologie, 102, 175–202.

166Steurbaut, E. & King, C., 2017. The composite Kortrijk section (W Belgium): a key reference for mid-Ypresian (Early Eocene) stratigraphy in the southern North Sea Basin. Geologica Belgica, 20/3-4, 125–159. http://dx.doi.org/10.20341/gb.2017.008

167Steurbaut, E. & Nolf, D., 2021. The Mont-des-Récollets section (N France): a key site for the Ypresian-Lutetian transition at mid-latitudes – reassessment of the boundary criterion for the base-Lutetian GSSP. Geodiversitas, 43/11, 311–363. https://doi.org/10.5252/geodiversitas2021v43a11

168Steurbaut, E., King, C., Matthijs, J., Noiret, C., Yans, J. & Van Simaeys, S., 2015. The Zemst borehole, first record of the EECO in the North Sea Basin and implications for Belgian Ypresian - Lutetian stratigraphy. Geologica Belgica, 18/2-4, 147–159.

169Steurbaut, E., De Ceukelaire, M., Lanckacker, T., Matthijs, J., Stassen, P., Van Baelen, H. & Vandenberghe, N., 2017. The Mons-en-Pévèle Formation, 09/01/2017. National Commission for Stratigraphy Belgium. http://ncs.naturalsciences.be/lithostratigraphy/Mons-en-Pevele-Formation, accessed 18/01/2025.

170Storms, R., 1896. Première note sur les poissons wemmeliens (Eocène supérieur) de la Belgique. Bulletin de la Société belge de Géologie, de Paléontologie et d’Hydrologie, 10, Mémoires, 198–240.

171Taverne, L. & Nolf, D., 1979. Troisième note sur les poissons des Sables de Lede (Eocène belge) : les fossiles autres que les otolithes. Bulletin de la Société belge de Géologie/Bulletin van de Belgische Vereniging voor Geologie, 87/3 (pro 1978), 125–152.

172Trif, N., Codrea, V. & Arghius, V., 2019. A fish fauna from the lowermost Bartonian of the Transylvanian Basin, Romania. Palaeontologia Electronica, 22.3.56, 1–29. https://doi.org/10.26879/909

173Underwood, C.J., Ward, D.J., King, C., Antar, S.M., Zalmout, I.S. & Gingerich, P.D., 2011. Shark and ray faunas in the Middle and Late Eocene of the Fayum Area, Egypt. Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association, 122, 47–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pgeola.2010.09.004

174Vandenberghe, N., Van Simaeys, S., Steurbaut, E., Jagt, J.W.M. & Felder, P.J., 2004. Stratigraphic architecture of the Upper Cretaceous and Cenozoic along the southern border of the North Sea Basin in Belgium. Netherlands Journal of Geosciences / Geologie en Mijnbouw, 83, 155–171. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0016774600020229

175Van Den Eeckhaut, G. & De Schutter, P., 2009. The elasmobranch fauna of the Lede Sand Formation at Oosterzele (Lutetian, Middle Eocene of Belgium). Palaeofocus, 1, 1–57.

176Vincent, E. & Lefèvre, T., 1872. Note sur la faune laekenienne de Laeken, de Jette et de Wemmel. Annales de la Société royale malacologique de Belgique, 7, 49–79.

177Vincent, G. & Rutot, A., 1879. Coup d’œil sur l’état actuel de l’avancement des connaissances géologiques relatives aux terrains tertiaires de la Belgique. Annales de la Société géologique de Belgique, 6, 69–155.

178Ward, D.J., 1979. Additions to the fish fauna of the English Palaeogene. 3. A review of the Hexanchid sharks with a description of four new species. Tertiary Research, 2/3, 111–129.

179Ward, D.J., 1980. The distribution of sharks, rays & chimaeroids in the English Palaeogene. In Hooker, J.J., Insole, A.N., Moody, R.T.J., Walker, C.A. & Ward, D.J. (eds), The Distribution of Cartilaginous Fish, Turtles, Birds and Mammals in the British Palaeogene. Tertiary Research, 3/1, 13–19.

180Ward, D., 2016. An Illustrated Guide to the British Middle Eocene Vertebrates. 2nd ed., Open-access pdf edition, 59 p.

181Winkler, T.C., 1873. Mémoire sur des dents de poissons du terrain bruxellien [issued as a separate by the Archives du Musée Teyler in 1873]. Archives du Musée Teyler, 3/4, 295–304. [The volume 3 was published in 1874].

182Winkler, T.C., 1874a. Mémoire sur quelques restes de poissons du système heersien [issued as a separate by the Archives du Musée Teyler in 1874]. Archives du Musée Teyler, 4/1, 1–15. [The fascicule 1 of the volume 4 was published in 1876].

183Winkler, T.C., 1874b. Deuxième mémoire sur des dents de poissons du terrain bruxellien [issued as a separate by the Archives du Musée Teyler in 1874]. Archives du Musée Teyler, 4/1, 16–48. [The fascicule 1 of the volume 4 was published in 1876].

184Zhelezko, V.I. & Kozlov, V.A., 1999. [Elasmobranchii and Palaeogene biostratigraphy of Transural and Central Asia]. Materialy po stratigrafii i paleontologii Urala, 3, 1–324. [In Russian].

185Manuscript received 14.04.2025, accepted in revised form 20.10.2025, available online 18.12.2025.

186Supplementary material for this paper is available online at https://doi.org/10.20341/gb.2025.007. This Supplementary material reproduces in full the report prepared by Dr Jacques Herman: Herman, J., 1998. Papenboskant excavation, archived at the Belgian Geological Survey (BGS) as 73W324.

Plate 1. Elasmobranch teeth, base of the Asse Clay Member, Papenboskant (Wolvertem). Scale bar = 1 mm. 1–3, 5–11: Lingual (A) and labial (B) views. 4: Occlusal (A), basal (B) and profile (C) views. 1A–B. Jaekelotodus trigonalis (Jaekel, 1895), IRSNB P 10784. 2A–B. Striatolamia macrota (Agassiz, 1843), IRSNB P 10783. 3A–B. Physogaleus secundus (Winkler, 1874b), IRSNB P 10777. 4A–C. ‘Myliobatis’ sp., IRSNB P 10796. 5A–B. Abdounia lapierrei Cappetta & Nolf, 1981, IRSNB P 10776. 6A–B. Abdounia minutissima (Winkler, 1873), IRSNB P 10774. 7A–B. Abdounia beaugei (Arambourg, 1935), IRSNB P 10775. 8A. Isistius trituratus (Winkler, 1874b), IRSNB P 10786. 9A–B. Rhizoprionodon ganntourensis (Arambourg, 1952), IRSNB P 10778. 10A–B. Squalus minor (Daimeries, 1888), IRSNB P 10785. 11A–B. Squatina cf. prima (Winkler, 1874a), IRSNB P 10787.

Plate 2. Elasmobranch teeth, base of the Asse Clay Member, Papenboskant (Wolvertem). Scale bar = 1 mm. 1–4: Lingual (A) and labial (B) views. 5–12: Occlusal (A), basal (B) and profile (C) views. 1A–B. Foumtizia sp., IRSNB P 10782. 2A–B to 4A–B. Pachyscyllium gilberti (Casier, 1946), IRSNB P 10779-10781. 5A–B, 6A–B. ‘Pseudobatos’ steurbauti (Cappetta & Nolf, 1981), IRSNB P 10788-10789. 7A–B. Glaucopristis bruxelliensis (Jaekel, 1894), IRSNB P 10791. 8A–B. ‘Rhynchobatus’ vincenti (Jaekel, 1894), IRSNB P 10790. 9A–B to 12A–C. Casierabatis spp., IRSNB P 10792-10795.