- Accueil

- N° 7 (2017) / Issue 7 (2017)

- Growing up in a changing world. A case study among Baka children (southeastern Cameroon)

Visualisation(s): 5194 (32 ULiège)

Téléchargement(s): 186 (0 ULiège)

Growing up in a changing world. A case study among Baka children (southeastern Cameroon)

Document(s) associé(s)

Version PDF originaleRésumé

Grandir dans un monde qui change. Les enfants Baka (sud-est Cameroun). Alors que de nombreuses études ont exploré les impacts des pressions multiples vécus par les sociétés de petite échelle sur les modes de vie des adultes et sur le maintien de leur savoir culturel, peu se sont concentrées sur la façon dont les enfants chasseurs-cueilleurs de ces sociétés vivent ce contexte changeant. Cette étude ambitionne de faire le bilan sur la façon dont les enfants sont touchés par ce processus de changement, et y sont impliqués, et comment il affecte leur vie quotidienne comme leur apprentissage culturel. En travaillant auprès des Baka, petite société du Bassin du Congo confrontée à de nombreux changements depuis plus de 50 ans, j'analyse la vie quotidienne des enfants Baka, ainsi que leurs perceptions de leur propre culture et leurs attentes vis-à-vis de leur avenir. Les résultats de ce travail montrent que leur quotidien et leurs perceptions sont intimement liés à leurs attenes vis-à-vis du monde des adultes. Ces résultats sont discutés à la lumière de la spécificité de l'enfance Baka et de l'influence des tendances générales véhiculées par les acteurs externes sur les perceptions Baka.

Abstract

While many studies have explored the impacts of the multiple pressures faced by small-scale societies on adult livelihoods and on the maintenance of their cultural knowledge, few have focused on the way hunter-gatherer children are living in this changing context. This study aims to assess how children are both affected by and involved in this process of change, and evaluate how the different changes might impact children's daily life and cultural learning. By working among the Baka, a small-scale society from the Congo Basin who have been facing several changes for more than 50 years, I analyze Baka children's daily life and perception toward their own culture and their expectation toward their future. The results of this work show that children's daily life and perceptions are intimately related to their expectations toward adulthood. These results are discussed on the light of the specificity of Baka childhood and the influence of general trends conveyed by external actors on Baka perceptions.

Abstracto

Crecer en un mundo que cambia. Los niños Baka (sureste de Camerún).Mientras que muchos estudios han explorado los impactos de las múltiples presiones vividas por las sociedades de pequeña escala sobre los modos de vida de los adultos y la conservación de su saber cultural, pocos se han centrado en cómo los niños cazadores-recolectores viven en este contexto de cambio. Este estudio explora cómo los niños están afectados por este proceso de cambio y cómo afecta su vida diaria y su aprendizaje cultural. Trabajando con los Baka, pequeña sociedad de la Cuenca del Congo viviendo muchos cambios en más de 50 años, analizo la vida cotidiana de los niños Baka y sus percepciones de su propia cultura y sus expectativas vis-à-vis de su futuro. Los resultados de este estudio muestran que su vida cotidiana y sus percepciones están estrechamente vinculadas a sus aspiraciones para el mundo adulto. Se discuten estos resultados a la luz de la especificidad de la infancia Baka y la influencia de las tendencias generales transmitidas por los actores externos en las percepciones de los Baka.

Table des matières

Introduction

1Worldwide, small-scale societies whose livelihoods are based on subsistence activities are facing the increasing pressure of external actors arriving in and acting upon their territories. In tropical regions where biodiversity is high, new economic activities, such as logging, large-scale farming, oil-palm plantations and oil and gas extraction are important drivers of change (Laurance 2015). In this sense, local societies are faced with several challenges, including the reduction of their land access and the restriction of natural resource use, which have led them to adapt their ways of life to these changing conditions. In these societies, whose livelihoods are intimately based on their relation with their environment, both ecological knowledge and practices are crucial for their subsistence. Because of the importance of the impacts of such changes on cultures and societies, many scholars have tried to assess how such changes are affecting cultural practices and knowledge (see for instance Gómez-Baggethun & Reyes-García 2013; Ohmagari & Berkes 1997; Zarger & Stepp 2004). Several studies revealed that the process of globalization has implied differential consequences on ecological knowledge (Reyes-García 2015). From the loss to the maintenance of ecological and cultural knowledge (Byg & Balslev 2004; Guest 2002), these studies highlighted that the impacts of changes vary largely according to their origins, to the social and ecological context, but also to the society affected by them. Therefore, it seems more than crucial to understand how a society and its corpus of knowledge might be affected by the drivers of change, by taking an exhaustive and local approach.

2Coherent with the reduced attention devoted to childhood in anthropology during several generations of researchers (Delalande 2009; Hirschfeld 2002), most of the studies that have assessed the impacts of changes among local societies have focused mostly on adulthood. However, as children are an integral part of their society and culture, they are facing the different changes occurring within their society (Thompson 2012). Moreover, as children are also “adults-to-be”, what children live today largely shapes what they would be in the coming years, and more specifically, how their knowledge and practices – their culture – might evolve through time (Lenclud 2003). This is especially the case among small-scale societies in which the learning of cultural and ecological knowledge is happening at an early stage of the lifespan. Indeed, a large amount of cultural knowledge is generally acquired before adolescence, and even before the age of 12 years old (Hewlett et al. 2011; Hunn 2002; Zarger 2002). In such societies, the acquisition of their cultural and ecological knowledge is embedded in their daily activities, thanks to an intimate relation with both their ecological and social environments, where the children use all their senses to observe, reproduce and embody what they are learning (Gaskins & Paradise 2010; Rogoff et al. 2007; Zarger 2010). In the specific case of small-scale societies – where children maintain a high autonomy and are respected in their decision-making – their curiosity, desires and expectations towards their own life lead their daily lives (Hewlett 2014a). In this sense, it seems crucial to approach local perceptions of their own daily life and culture, in order to better understand what are the main drivers of their daily activities and their process of learning.

3Thus, in order to bring new elements of understanding of the impacts of the drivers of changes among small-scale societies, I aimed to assess how such processes are affecting both children’s daily activities and perceptions. To do so, I have worked with the Baka, a hunter-gatherer society in the Congo Basin that has been facing several drastic changes for more than 60 years. I wondered how the impacts of changes faced by the Baka and the different actors entering in their territory might impact Baka children's daily life and perceptions towards their own livelihood and culture.

Case Study

4The Baka are one of several hunter-gatherer groups living in the tropical forests of the Congo Basin. Most Baka live in Cameroon, where their population is estimated between 30,000 and 70,000 individuals, while some groups are also found in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Central African Republic and Gabon (Leclerc 2012).

5As in other tropical regions, southeastern Cameroon has faced the arrival of several new economic activities, significantly affecting standards of living of previously autarkic populations (Ernst et al. 2013). For decades, the Cameroonian tropical forest has witnessed the opening of mining and logging concessions, first from European, then from American, and more recently from Asian companies (Ichikawa 2006). The improvement of the transport system offered by these companies, has also brought poachers, and bushmeat and ivory traders to the area, together having a large impact on the local ecological system (Bennett 2014; Taylor et al. 2015; Wilkie et al. 2011). In response to these changes, international institutions and policy-makers have promoted biodiversity conservation programs as well as the creation of natural parks, faunal reserves, and wildlife sanctuaries. Thus, local populations with a long history of interaction with the environment and dependent on natural resources for their subsistence now face considerable changes in terms of access and use of natural resources, and by consequence have to adapt their livelihood strategies (Ichikawa 2001).

6Highly nomadic until the beginning of the 1960s, the Baka traditionally used to follow a seasonal migration between different forest camps. Their livelihood was based on the use of forest resources and the exchange of products with farmer neighbors. With the development of new economic activities in the area, the Baka have witnessed the gradual reduction of access to forest resources, especially to game and edible wild plants. Consequently, they have gradually abandoned their forest camps for more permanent villages along logging roads. This shift has been reinforced both by missionaries and by national policies – such as the extensive sedentarization program instituted in Cameroon since the 1950s – which led many Baka to reduce their mobility (Althabe 1965; Bahuchet et al. 1991; Bailey et al. 1992; Leclerc 2012). Today most Baka live in villages close to neighboring Bantu-speaking villages. They have also progressively started to engage in agricultural activities by opening their own plots (Leclerc 2012) and many Baka children now have the opportunity to attend school (Kamei 2001). Thus, nowadays, albeit with many variations, most Baka live in permanent settlements, engage in agricultural work, both providing wage labor for their farming neighbors and in their own plots. They still remain highly dependent on forest resources, for both their diet and subsistence, but the different combinations of one or another activity has resulted in the Baka developing a range of different living strategies (Yasuoka 2012).

Methodological approach

Research setting

7This research took place among several Baka communities from southeastern Cameroon, in the districts of Lomié and Messok, in the Haut-Nyong Department. I conducted 18 months of fieldwork, from February 2012 to August 2013, in two communities with about 300 residents each (of which about half were children). Before starting data collection, I obtained free prior and informed consent in the two villages and from every individual participating in the study. As the study involved interviewing children, I obtained the consent of the parents of the children I worked with. This study adheres to the Code of Ethics of the International Society of Ethnobiology and received the approval of the ethics committee of the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (CEEAH-04102010).

Methods of data collection and analysis

8I used a mixed-methods approach collecting both qualitative and quantitative data. I collected qualitative data on adults’ and children’s daily life and perceptions using semi-structured interviews and participant observation by interacting with as many households as possible. While living in the villages, I followed local socio-cultural norms, e.g. on sharing, cooking and children caretaking; I also participated in the daily life of neighboring households sharing with them daily life activities, such as washing clothes or cooking, or accompanying them on fishing expeditions, to their forest camps, or to their agricultural plots. I alternately worked with Baka and Nzime (one of the Bantu-speaking ethnic groups from the area) translators who were both fluent in French and Baka languages. However, as fieldwork advanced and as I improved my competency in Baka language, I developed closer interactions that provided more intimate and accurate data on Baka adult's and children's daily life. Close interactions with people favored my acceptance and gained me the trust of Baka adults and children. My work with children was facilitated by children's own curiosity and desire to spend time with foreigners, a situation also reported in similar contexts (i.e., see the work of Bird-David 2005 among the Nayaka).

9First, I conducted a census to collect socio-demographic data of all the individuals in the village, gathering individuals’ age, sex, clan, the number of siblings by family, and their level of education. As most Baka cannot recall their date of birth or have birth records, I used kinship information (i.e., order of birth) to estimate the age of children in our sample.

10Second, I collected data on the Baka's general perception of childhood and adulthood and on their daily activities. To begin, I asked children to list the activities they prefer to undertake during the day. I then asked them to list the skills needed to become a competent adult. Data on preferred activities were collected through structured interviews with 47 children from 5 to 16 years old, including 24 girls and 23 boys. In order to assess the impacts of the drivers of changes among the Baka, I specifically focused on sedentarization, access to schooling and to electricity, and also to the news sources of income led by external actors. During the interviews with children, I systematically asked them to report the place they prefer to live (forest camp vs village) and the reasons why, their perceptions towards schooling, if they were performing a job (and if so, what kind) and what they spent money on.

11Then, in order to assess adults’ perceptions, I asked adults to list the skills they consider a child has to learn to become an adult. Given the important differences between girls’ and boys’ daily life, I asked these two questions separately in relation to boys and girls. I then completed the interview with open-ended questions about changes in knowledge and practices since their childhood. I interviewed a total of 25 adults, 11 women and 14 men, ranging from 20 to 70 years old.

12I analyzed answers to children’s preferred activities and expectations towards adulthood's competences using the free-listing procedure in Flame (Pennec et al. 2012). To do so, I subdivided the sample and compared the differences in the most salient answers given by boys and girls. Then, I then compared the percentage of answers reported according to their household profile. I ran similar analysis for adult's answers on their expectations towards what girls and boys should learn to be competent adults. I compared the most salient answers given by adults according to their household profiles. Finally, I compared children’s and adult’s answers related to their expectations in regards to which skills girls and boys should learn and master to be a competent adult.

13This extensive period of fieldwork allowed me to observe the different actors interacting with the Baka all across the seasons. Thanks to the collaboration of local teachers, I followed school attendance in both villages. Moreover, I could follow both children and adults when performing their subsistence activities but also their daily leisure, such as attending evening events in unofficial bars. Finally, I gathered complementary information among Nzime people, holding local stores and bars, employing Baka adults and children, and the foreigners coming to the villages in order to offer jobs to Nzime and Baka people (mostly unofficial loggers) or to buy bushmeat and Non Timber Forest Products (NTFP).

Baka childhood

Child development

14As the notion of childhood varies across cultures (Lancy 2008), I first describe some aspects of Baka childhood that help contextualizing our results, namely Baka emic description of child development and cultural patterns of child caring.

15Even before birth, Baka children-to-be receive attention and have a specific position in the household and the village. For example, to ensure the physical and spiritual health of the infant-to-be, both the pregnant woman and her partner have to respect several restrictions, including dietary prohibitions on the consumption of wild animals and plants. The first months of the infant, called dindɔ, are perceived as a critical period in Baka life. During this period, the Baka recognize a triangular relation between father/mother/infant that seems to shape many daily activities. For example, during infancy parents restrict some practices during the performance of hunting, gathering, and fishing expeditions, as prescribed by cultural prohibitions regulating diet and activities performance. Men are also warned against having sexual relations with other women. Failure to follow such restrictions is believed to cause abortion or an illness for the newborn. While most restrictions are limited to the pregnancy and the first months of an infant’s life, some are prolonged until weaning. Interestingly, weaning represents not only the onset of children’s autonomy, a condition that starts as soon as the child begins walking, but also the end of these children’s social norms that regulate parents’ behaviors. Once weaned, and concomitant with their first steps, children are called yandε.

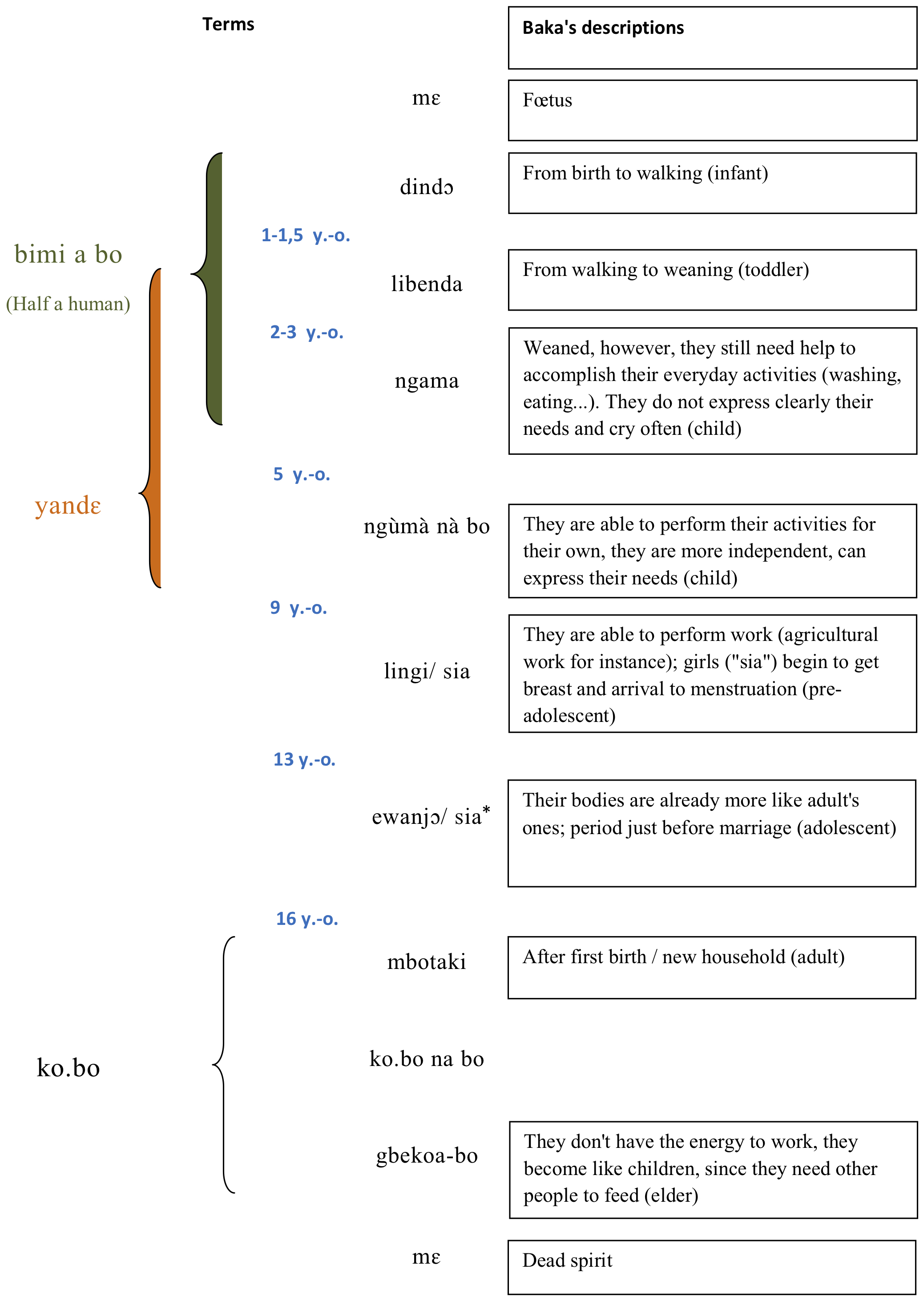

16Then, Baka differentiate several stages of child development: ngùmà nà bo, that relates to middle childhood, lìngìand sia (for boys and girls respectively), which corresponds to preadolescence and ?èwanjɔ for boys and sia for girls entering adolescence (cf. Figure 1 below). Once a person establishes his or her household, and especially after the arrival of the first child, young adults are then considered ko.bo nà bo, or adults. However, once children enter into yandε stage, they are also considered ko.bo, as they are supposed to be able to make their own decisions and to be responsible for their own actions. Common to several hunter-gatherer societies from the Congo Basin (Hewlett 2014b), Baka children hold a high level of autonomy and are seen as entire beings, and respected as such.

Figure 1: Terminology of the individual development during lifespan. Elaboration based on previous literature and focus group interviews with Baka adults

17NB: There were some differences between what Baka people reported us about lingi, sia and ewanjo and what Brisson (2010) and Joiris (1998) wrote. For these authors, adolescents boys and girls are called ewanjo, however, Baka told us ewanjo was only used for boys. Also, the term sia is used both for preadolescents and adolescents; however, the Baka that we interviewed told us that there is a first stage of sia, the youngest sia and then the oldest sia, without establishing a clear distinction between what Brisson and Joiris consider as preadolescence and adolescence.

18Few rituals exist uniquely for boys among the Baka. The first common ritual, originally performed by Bantu-speaking people, is the boys’ circumcision, bèkà(Joiris 2003). This ritual is generally performed around six years old, but might be also performed on boys until early adolescence. Once the boy is circumcised, Baka people say that he is then a “real adult”; however, this ritual is not needed for entering adulthood. The other young boy’s ritual embedded in Baka culture relates to their initiation to the jengi, the main and most powerful spirit of the forest. Considered to be apart of entering the social world of male adults, this initiation confers to the individual aptitudes intimately related to forest skills, especially in relation to hunting. For girls, the Baka generally consider that they become ‘real women’ after giving birth for the first time.

Children’s daily activities and knowledge

19In this context, Baka children are asked from early childhood to help their parents with small domestic tasks that allow them to interact with and discover their environment. In general, the youngest ones are asked to carry tools (such as a pot, a machete, etc.) or to take some food to be shared with other households in the village. It is very common to see young children walking around the village carrying pot with food or other diverse tools. By doing so, according to adults' insights, young children learn the name of the different elements of their surroundings, including for instance the cooking tools, the plants and food prepared, as well as the use of these items, by observing others using them.

20Then, once children enter middle childhood, they are usually asked to more participate in the household maintenance, such as by going to collect firewood or to fetch water from the closest river. During these times, children evolve singly or in pairs and learn from their environment. Baka adults always reported that these situations are key moments for the first acquisition of knowledge and practices related to their subsistence. Indeed, by going to fetch water, for example, children take also time to observe the river and banks in order to find little animals or fishes.

21Most of Baka children's time is devoted to subsistence related activities. From an early age, they are highly involved in hunting, gathering, fishing and performing agricultural tasks. Thanks to this high involvement, children actively learn both knowledge and practices related to subsistence (Gallois et al. 2015). As shown previously (Gallois et al. in press), Baka children acquire a large amount of traditional ecological knowledge from an early age, as they know a similar number of plants, animals, and other edible and medicinal plants than adults and show similar knowledge in relation to ecological uses and practices. Their knowledge is early differentiated according to sex, with boys who tend to hold more knowledge related to animal and hunting practices than girls, echoing adult's differentiation of knowledge (Gallois et al. in press).

22Behind the early acquisition of ecological knowledge also reported among other small-scale societies (Hewlett 2014a), Baka children seem to hold a specific set of knowledge and practices that are not shared with adults. Baka children are experts on small animals, especially rodents and birds, and hold knowledge Baka adults do not, especially in relation to hunting techniques; this allowed us to infer the presence of a Baka child culture related to ecological knowledge (Gallois et al. in press).

23Finally, this specificity of Baka childhood knowledge, almost detached from adults knowledge, echoes their daily life that also occurs far from the realm of adults, as Baka children mostly performed their daily activities without the presence of a parent, and very few times with other adults (Gallois et al., n.d.). As Baka adults respect children’s choices and allow them to be independent from an early age, children spent a large amount of time amongst themselves. They go hunting, gathering and fishing mostly in mixed age groups or with peers. This high autonomy in their daily life suggests the importance of the horizontal pathway of transmission (knowledge transmitted between individuals of the same generation) in Baka children’s learning processes (Gallois et al., n.d.).

Impacts of changes among Baka children’s daily life

24Coherent with the high level of autonomy and independence of Baka children, social and ecological changes faced by the Baka differ between adults and children. Baka adults present different strategies of livelihood, from the ones based principally on hunting and gathering to others depending mostly on agriculture and unskilled work performed for the Nzime. However, Baka children’s daily life does not seem to be affected by their parents’ livelihood strategies, as shown in a previous work (Gallois et al. 2016).

25For these reasons, it seemed relevant to further explore the main drivers of Baka children's daily activities and how current changes affect children’s daily lives, and to look at Baka’s perceptions related to their own livelihood and their expectations for the future.

Impact of sedentarization

26Almost all the families present in both communities have a house in the village, and generally have their own forest camps, a location that is used during the fructification of non-timber forest products (NTFPs). When asking children about the place they prefer to live, of the 47 interviewed, 40 reported preferring living in the village. Only 5 preferred the forest camp as a living place. The main reasons they reported for this preference to the village were because “in the village there is a lively atmosphere”, and in the forest “we don't have anything to do”. Only a handful (6) reported that they liked to live in the village because of the school.

27Even if children seem to prefer to live in the village, they reported they like to go to the forest during the main fructification of NTFPs, or to go hunting and fishing. In this sense, children appreciate going to forest camps mostly for what the forest might procure, for short-term expeditions.

28“I like going to the forest to collect màɓè [Baillonella toxisperma, Sapotaceae]and mbalaka [Pentaclethra macrophylla, Caesalpiniaceae] and staying there a few days. But not too long. Mam and Dad used to stay too long in the forest. I have nothing to do more; so I come back to the village”.

29Exception made of the moments where the families are moving to the forest, this implies that even if a child's family has left during several days in their forest camp, children tend to stay a short time there and to go back to the village quickly, without their parents. Indeed, it was common to see groups of children alone in the forest or along the logging road, walking on their way back to the village. There, they might stay several days, or up to several weeks, sleeping in extended family members’ houses. They stay in order to go to school (for a few), but mostly to be present when there are moments of music and dance at night in the local bars.

30More than illustrating the detachment of Baka children from parental livelihood, this is also intimately related to our second point, on the impact of electricity access into Nzime and Baka communities.

Access to electricity

31The arrival of new actors has also resulted in the coming of new products into the area, with the recent ingress of Chinese products. Among other items, cheap motorbikes have considerably increased the movements in the area and nowadays at least one motorbike is present in every Nzime village, allowing many Nzime men to work as mototaxi drivers. Easier transportation has also accelerated the spread of alcohol and audio equipment, which allowed the establishment of unofficial musical bars in almost all the Nzime’s villages – and also in some Baka villages.

32Moreover, in almost all the Nzime communities, and in an increasing number of Baka areas, at least one person, generally the main trader of the village has a generator. This helps him to feed a fridge or lights with energy, but also to be able to create events at night, by putting both the light and the radio, and sometimes even the television on. In both studied villages, there was at least one Nzime with his own store and audio equipment. Thus, depending on the economic resources of the owner of these small unofficial bars, who is the one providing the gasoline fuel needed for the generator to work, musical nights would occur from once a week to every night.

33Such events are highly attractive to Baka people, adults and children equally, as also reported previously (Oishi & Hayashi 2014; Townsend 2015; Weig 2015), and create a recreational space where both Nzime and Baka people dance, smoke and drink all kinds of alcohol.

34Once the night arrives, these places become neuralgic points. Regardless the distance they have to travel, be it a few meters or several kilometers, Baka adults go to these bars. Children do as well, but their parents are commonly unaware of these outings. During such moments, children dance, play and sometimes also drink small 40-50 ml plastic bags of strong alcohol. This occurs among children from an early age, as even children from five years old reported to us having drunk the previous day.

35Although attending adults are supposed to keep an eye on the children, most adults do not, especially when the influence of alcohol is felt stronger. During such evenings, children tended to hide by dancing and playing mostly in the shadow, keeping distance from the adults. It was frequent to see passing through their hands little bags of alcohol, bought by the oldest ones, and shared among all, including the youngest ones.

36For parents who stayed in the village, they feel somewhat helpless about this situation and even if they punish their children when they come back, few are the ones who really have an impact on them.

37A father with four children reports:

38“Even during the night children might leave the forest camp; and then, they go back to the village, they go there in order to dance and to attend music events at the bar. What can I do for that? Even if I say something and try to punish them, they just ignore me and answer that I can't understand, I do not know what is happening there”.

39More than a conflict between generations, there is also an inadequacy of the past way that Baka adults used to teach and educate their children, to the current situation. The traditional way of educating children, based on independence, autonomy and the need to adopt new methods is now quite challenging for Baka adults.

Schooling

40Two main kinds of school are accessible for the Baka: a public one, receiving both Nzime and Baka children; and a private one, reserved only for the Baka and mostly led by missionaries (in our studied case, by the NGO Frères des Écoles Chrétiennes). Among the public school, the NGO Plan Cameroon was working in some villages on programs specific for Baka children by promoting a bi/multilingual education, based on Baka's daily life, and on helping the Baka economically for supplies and fees.

41In both communities, Baka children's daily life was minimally impacted by schooling, as they were attending school very occasionally. For instance, for the schooling year 2012-13, only about 56% of the children of age to attend school were actually registered in the schools of the studied villages. The community with a public school presents the lowest attendance, with only 44% of the children of age doing so, in contrast with the other community with a private school, where almost 74% of the children attended school. However, even if children were registered at school at the beginning of the schooling year, school attendance decreased over the course of the year. Moreover, the attendance to school decreases drastically after the second year: very few children follow the schooling cycle more than one or two years. Therefore, in general, most Baka children and adults who attended school only reached the SIL level (Section d’Initiation au Langage), a pre-curricula level that aims to familiarize children with French language.

42Besides the high level of teachers’ absenteeism that equally affects all ethnic groups, two reasons might explain the specifically low attendance of the Baka children: the unsuitability of class content to Baka livelihood, and the unsuitability of the schooling schedule to Baka seasonal migration, among others. However, from Baka children's words, many reported they were not attending school because of a lack of supplies or clothes. In the case of public school, the fees of registration and school stationary were one of the hindrances to attend school, as Baka people do not generally save money, they typically do not have enough money to pay all the expenses related to school. Thus, the access to school for Baka children who do not have all the school stationery depends on the indulgence of the school director. However, most of the time, children who do not have enough money or material prefer not to go to school because they feel ashamed, a feeling that is generally enhanced by Nzime children’s taunts towards Baka children. Thus, many children quickly leave school. Because children generally don't eat breakfast in the morning, they go directly to their snares to look for prey or gather surrounding edibles before going to school, or during the morning break. In general, they do not return to school afterwards. Confronted with this situation, parents felt generally helpless, as they lately realized their children did not go to school at the end of the day, when they come back from work, and many parents reported to us they did not know what to do to make their children attending school.

Market economy

43Baka children’s access to the market economy is mostly through two different channels: the labor they offer to neighbors and/or the commercialization of forest products.

44The Baka have always performed agricultural work for their neighbors, and children also actively participate in this activity, by either accompanying adults or going for their own. When children are performing a job alone, or in groups of peers, they are paid directly by the Nzime, either in food or in cash. For this reason, when children are hanging around during the day, they frequently go to the Nzime village in order to look for small jobs. In general, middle childhood children perform domestic tasks such as fetching water or gathering firewood. Once this work is done, children then receive food or buy food with the money they have earned. Indeed, when asked, children between 6 and 12 years old reported to us that they buy sweets or local doughnuts mekala, but also rice and other edibles.

45Children also have access to money thanks to the different traders coming into their territories. Children participated to the gathering of NTFP, such as màɓè and mbalaka, either with their families for the youngest ones, or alone or in groups of peers for the oldest. In one of the villages, during the production of mbalaka, a group of five adolescent boys was the most efficient in the gathering of such NTFP.

46Moreover, it was also common to see adolescent boys being hired by unofficial loggers. Joining other Baka men, adolescent boys would carry wood timbered from far in the forest to the logging road, and charged into the truck. With the money they earn, adolescent boys and girls reported spending it first on clothes and then on food and alcohol.

Baka children’s perception on their own future

47In such context of changes, I then aimed to understand children's own perceptions towards their livelihood and their expectations for their individual future.

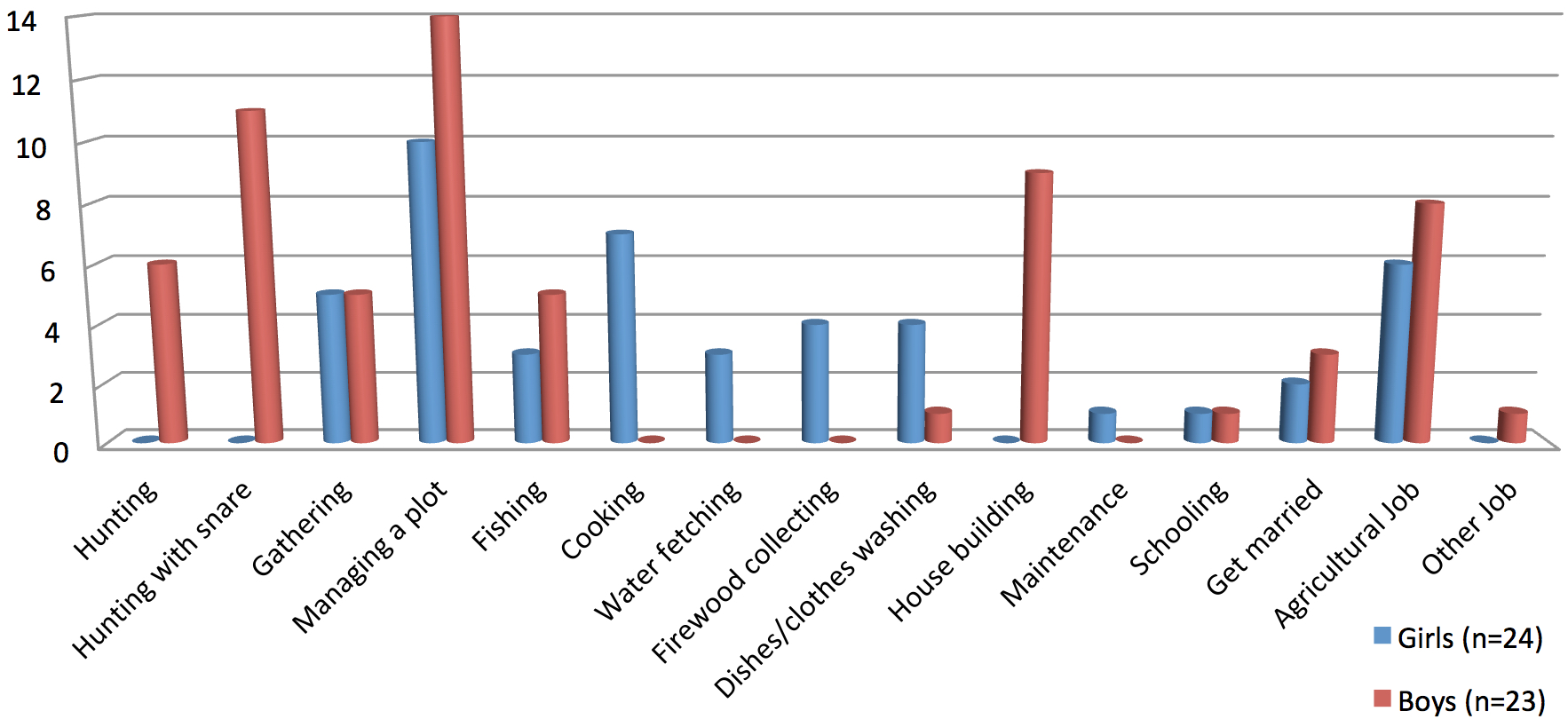

48When asking children about the future and the most important skills needed to become competent adults, both girls and boys mentioned getting and managing an agricultural plot (14 boys and 10 girls), gathering (5 boys and 5 girls), and working in Nzime’s agricultural plots (8 boys and 6 girls) (cf. Figure 2 below). For the rest of the activities, the number of children varied according to the sex of the respondent. Only boys reported hunting as an important activity to learn to become a competent Baka adult: six boys considered it important to know how to hunt in general and 11 to hunt with snares. Similarly, only boys (9 of them) reported building a house as an important activity to learn. In contrast, only girls listed activities related to household maintenance as important to become a competent Baka adult: seven girls listed cooking, 4 collecting firewood, and 13 fetching water.

Figure 2: Scores (in % of responses) of competences expressed by children of both sexes to be needed in adulthood

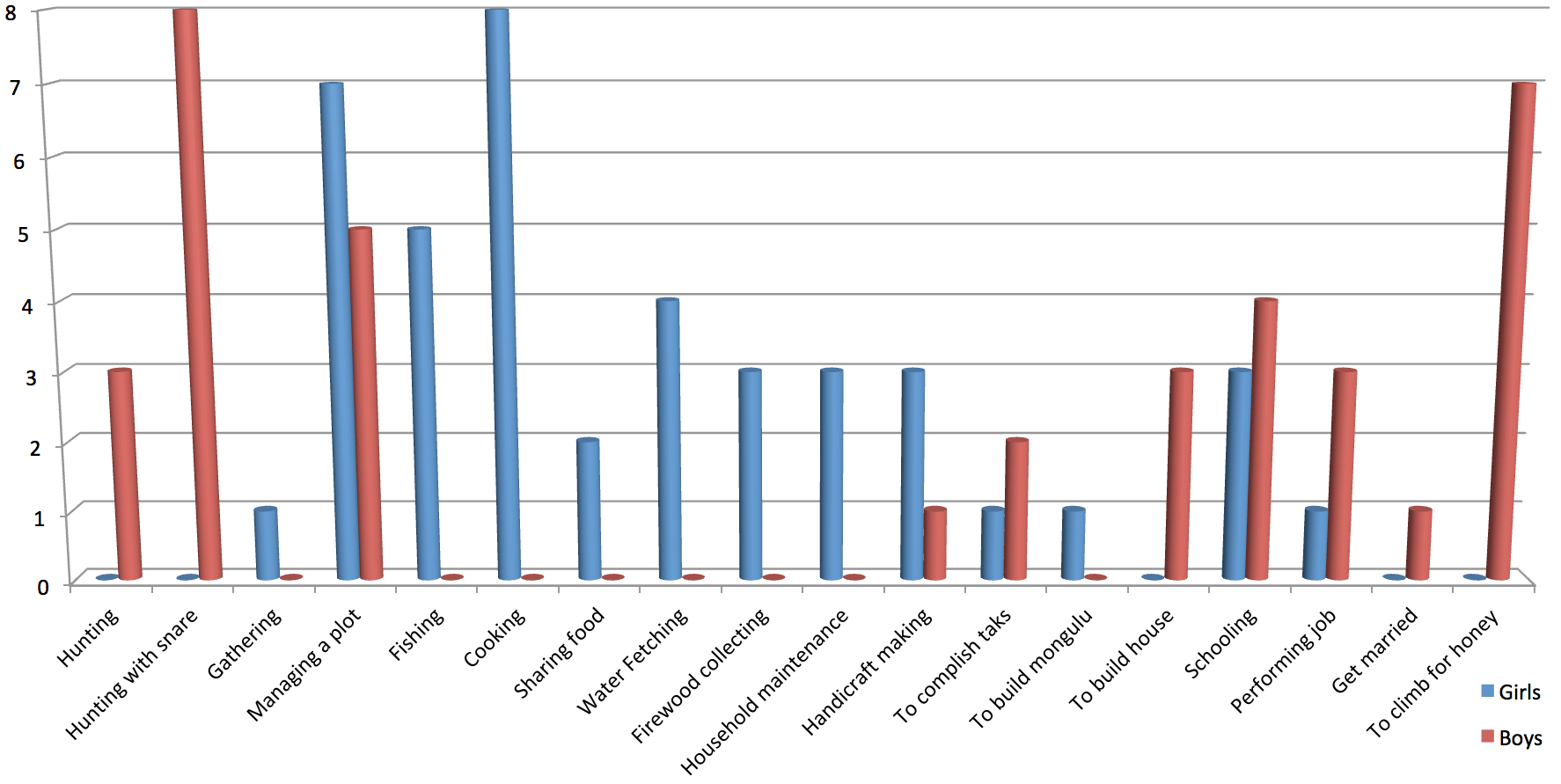

49In contrast with children’s expectations, interviewed adults considered that the essential competences boys need to learn before entering adulthood were setting snares, climbing trees, and managing a plot. They also mentioned attending school as an important childhood activity. Adults listed many more activities as essential for girls to learn, including attending household chores in general and cooking in particular, but also maintaining a plot and fishing (cf. Figure 3 below).

Figure 3: Scores (in number of adult respondents) of skill that boys and girls need to learn to become competent adults (n=25)

50Both adults and children highly ranked “getting and managing a plot” as a skill that has to be acquired before adulthood. Cooking for girls and hunting for boys were also skills highly ranked by both adults and children. The fact that both children and adults from a hunter-gatherer group consider managing a plot as a skill that needs to be acquired before becoming a competent adult shows the magnitude of the change operating among this group. We argue that the fact that this activity is so highly valued can be explained by how the development discourse conveyed by governmental and NGO programs has permeated Baka lives (Althabe 1965; Leclerc 2012). Such discourse promotes a lifestyle based on agriculture, sedentarization and schooling, activities that were separate from the realm of Baka activities until recently, but that – according to our results – seem to be highly valued now. By contrast, the importance of hunting for boys and household maintenance for girls seems to be more rooted in traditional Baka culture. As also reported in other hunter-gatherer societies (Noss & Hewlett 2001; Vonrueden et al. 2008), success in hunting continues to confer prestige to the Baka (Duda et al. unpublished). Similarly, women who are known to be excellent household keepers and good mothers are also highly appreciated among the Baka. In this sense, it is not surprising that these two activities continue to be highly valued.

51However, we also found some differences between adults and children's expectations. Children considered that conducting agricultural work for Nzime neighbors and gathering (specifically marketable NTFPs) were important skills to master during adulthood, whereas few adults mentioned them. Conversely, adults reported skills that were not reported by the children. Adults considered important that girls learn how to do handicrafts, especially basketry, but girls themselves did not mention this skill. Similarly, adults considered essential that boys learn how to climb a tree in order to gather honey, but neither boys nor girls mentioned this skill. Moreover, adults also reported that children have to know how to accomplish tasks that adults ask them to and that girls have to know how to share cooked food by learning, for example, the quantity to put according to the number of people in each household. Again, none of these skills were mentioned by the children. Furthermore, adults mentioned school attendance as an important activity to become a competent adult, but such activity was almost never listed by the children. These contrasts between children and adults' expectations are especially related to skills that refer to a more “traditional” and “modern” ways of living. For instance, although adults value schooling, handicraft making, and climbing trees, children do not report any of these activities as important for becoming competent adults, and furthermore, and they do not appear to perform them frequently (Gallois et al. 2015). While we have not analyzed whether there is a correspondence between the activities that children listed as important to become competent adults and the activities they actually perform, such analysis would provide important insights on the relation between perceptions and behavior.

52The lack of congruence between Baka children and adults’ expectations towards the needed skills to be competent adults might be largely explained by the large socio-ecological changes affecting Baka society nowadays. Indeed, the contrast between the skills that each of the two generations value might reflect influences of general trends conveyed by several external actors into the Baka communities, and the recent relevance that money has taken in Baka life. Indeed, as shown above and reported also in previous work (Kitanishi 2006), the arrival of traders, poachers and logging companies in Baka territories has led to a growing monetization of Baka life. Agriculture and hunting activities are thus highly valued because their derived products can be sold. At the same time, the ideas conveyed by the media, for example through video-clips and lyrics of new African hits, enhance this global trend of valuation of money and material possessions. For instance, recent studies reported that the performance of dances and the possession of audio material to play modern music brings the Baka a high feeling of pride and well-being (Townsend 2015; Weig 2015). This attraction to money and material goods, and therefore the preference for activities that might result in cash, is more present among adolescents and young adults. To some extent, it is not surprising that adolescents and young people tend to prefer activities from which they would obtain cash as, similar to what has been reported in other settings, “moving ‘beyond childhood’ and finally becoming a young adult is displayed, for example, by the possession of certain brands and type of clothes”(Buhler-Niederberger & van Krieken 2008: 152). Thus, we argue that children's choices of daily activities might be more influenced by general trends occurring in the communities rather than in their familiar nuclei.

53Therefore, as children's behaviors and expectations might not be approached by parental behaviors and expectations, it seems important to focus on children’s own behaviors and expectations in order to understand the potential impacts of changes on Baka childhood.

Conclusion

54In this study, we aimed to assess how the drivers of change faced by the Baka might affect not only their livelihood but also their perceptions towards their daily activities and culture. By doing so, we consider that we can assess not only how such changes impact a society but also how cultural practices and knowledge might evolve through time. In a society where childhood holds a high autonomy and where a large part of the learning process relies on children, what children from today might do, but also what they expect for their future give us accurate indicators of the kinds of knowledge and practices they would acquire.

55From generation to generation, groups of hunter-gatherers have maintained their cultural identities despite several cultural borrowings and their relation with non-pygmy groups. However, it is worth wondering, considering the rapid rate of changes, how the Baka will adapt. This is highly relevant considering that many aspects of their current livelihood show indicators of a society that is marginalized and that is losing its bearings (as it has been seen in many other small-scale societies). Previous scholars already reported the large impact of sedentarization on both health and well-being (Dounias & Froment 2006), with an alarming situation of alcoholism and an increasing atmosphere of jealousy and distrust (Leclerc 2006). Baka children's words and behaviors provide insights, or at least arouse questioning, on the potential future of their culture. Indeed, considering the increasing arrival of external actors in Baka territories and the Baka expectations towards a sedentary livelihood based on agriculture and cash providing activities, an important question emerges: How sustainable will it be for their ecological environment, their livelihood and their well being? This is especially alarming because most of their cash income activities rely on the exploitation of natural resources and, at the same time, few Baka deplore the impacts of deforestation on biodiversity as, for instance, on the population of animals in their area (Duda et al. 2017). In this sense, both perceptions towards their environment and their expectations towards their future, based on agriculture and cash providing activities, offer an opportune context for an increased exploitation of natural resources by local and external actors. It is then worth wondering how the development of such activities in the area would benefit the Baka. The Baka might have a short-term benefit from this exploitation, but it would come at the expense of the ecological environment that their subsistence relies on. Furthermore, it is highly probable that such a context of commoditization of natural resources would not allow the Baka to be better integrated as citizens, specifically because few Baka master the national language, have competences in numeracy or are involved in local leadership roles. Instead, it would rather maintain them in a situation of marginalization and exploitation of their labor force and ecological expertise.

56Therefore, it seems more than crucial to work on political and collaborative programs with local communities in order to identify with them how the Baka might adapt to this changing context. This has to be done by taking into consideration local perception and expectations of men and women, but also of adults and children.

Acknowledgements

The research leading to these results has received funding from the European Research Council under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Program (FP7/2007-2013) / ERC grant agreement No. FP7-261971-LEK. Ideeply thank Victoria Reyes-García, who led this project and allowed me to conduct this research among the Baka. I would like to share a special thanks to Romain Duda, who helped me with data collection and analysis, and also to Ernest Simpoh and Appolinaire Ambassa for their assistance with data collection. Thank you Morgan Jenatton for your useful comments. My deepest thanks go to all the Baka adults and children with whom I have lived and worked. This work contributes to the “María de Maeztu Unit of Excellence” (MDM-2015-0552).

Bibliographie

Althabe G. 1965 « Changements sociaux chez les Pygmées Baka de l’Est-Cameroun », Cahiers d’études africaines 5 : 561-592.

Bahuchet S., McKey D. & Garine I. 1991 « Wild yams revisited : Is independence from agriculture possible for rain forest hunter-gatherers? » Human Ecology 19(2) : 213-243.

Bailey R.C., Bahuchet S. & Hewlett B.S. 1992 « Development in the Central African rainforest : concern for forest peoples » (202-211), in K.M. Cleaver (ed.) Conservation of West and Central African Rainforest. Gland : International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resource.

Bennett E.L. 2014 « Legal ivory trade in a corrupt world and its impact on African elephant populations », Conservation Biology 29(1) : 54-60.

Bird-David N. 2005 « Studying children in ‘hunter-gatherer’ societies : Reflections from a Nayaka perspective » (92-102), in B.S. Hewlett & M.E. Lamb (eds.) Hunter-gatherer childhoods : Evolutionary, developmental, and cultural perspectives. New Brunswick : Routledge.

Brisson R. 2010 Petit dictionnaire Baka-Français. Sud Cameroun. Paris : L’Harmattan.

Buhler-Niederberger D. & Van Krieken R. 2008 « Persisting inequalities : Childhood between global influences and local traditions », Childhood 15(2) : 147-155.

Byg A. & Balslev H. 2004 « Factors affecting local knowledge of palms in Nangaritza Valley, Southeastern Ecuador », Journal of Ethnobiology 24(2) : 255-278.

Delalande J. 2009 « Pratiquer l’anthropologie de l’enfance en sciences de l’éducation : une aide à la réflexion » (103-112), in A. Vergnioux (ed.) 40 ans des sciences de l’éducation. Caen : Presses Universitaires de Caen.

Dounias E. & Froment A. 2006 « When forest-based hunter-gatherers become sedentary : Consequences for diet and health », Unasylva 57(224) : 26-33.

Duda R., Gallois S. & Reyes-García V. 2017 « Hunting techniques, wildlife offtake and market integration. A perspective from individual variations among the Baka (Cameroon) », African Study Monographs 38(2) : 1-30.

Ernst C., Mayaux P., Verhegghen A., Bodart C., Christophe M. & Defourny P. 2013 « National forest cover change in Congo Basin : Deforestation, reforestation, degradation and regeneration for the years 1990, 2000 and 2005 », Global Change Biology 19(4) : 1173-1187.

Gallois S., Duda R., Hewlett B. & Reyes-García V. 2015 « Children’s daily activities and knowledge acquisition : A case study among the Baka from southeastern Cameroon », Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 11(1) : 11-86.

Gallois S., Lubbers M., Hewlett B. & Reyes-García V. n.d. « Social networks and knowledge acquisition strategies among Baka children, southeastern Cameroon », submitted in October 2017 to Human Nature.

Gallois S., Duda R. & Reyes-García V. 2016 « ‘Like father, like son’ ? Baka children’s ethnoecological learning in a context of cultural change » (195-212), in A. Pyhälä & V. Reyes-García (eds) Hunter-gatherers in a changing world. New York : Springer.

Gallois S., Duda R. & Reyes-García V. in press « Local ecological knowledge among Baka children : a case of ‘children's culture’ ? » Journal of Ethnobiology 37(1).

Gaskins S. & Paradise R. 2010 « Learning through observation in daily life » (85-111), in D.F. Lancy, J.C. Bock & S. Gaskins (eds.) The anthropology of learning in child. Lanham : Rowman & Littlefield.

Gómez-Baggethun E. & Reyes-García V. 2013 « Reinterpreting change in traditional ecological knowledge », Human Ecology 41(4) : 643-647.

Guest G. 2002 « Market integration and the distribution of ecological knowledge within an Ecuadorian fishing community », Journal of Ecological Anthropology 6 : 38-49.

Hewlett B.S. 2014a « Hunter-gatherer childhoods in the Congo Basin » (245-275), in B.S. Hewlett (ed.) Hunter-gatherers of the Congo Basin : Cultures, histories and biology of African Pygmies. New Brunswick : Transaction Publishers.

Hewlett B.S. (ed.) 2014b Hunter-gatherer of the Congo Basin. Cultures, histories and biology on African Pygmies. New Brunswick : Transaction Publishers.

Hewlett B.S., Fouts H.N., Boyette A.H. & Hewlett B.L. 2011 « Social learning among Congo Basin hunter-gatherers », Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences 366(1567) : 1168-78.

Hirschfeld L.A. 2002 « Why don’t anthropologists like children ? », American Anthropologist 104(2) : 611-627.

Hunn E. 2002 « Evidence for the precocious acquisition of plant knowledge by Zapotec children » (604-613), in J.R. Wyndham, F.S. Zarger & R.K Stepp (eds.) Ethnobiology and cultural diversity. Athens : University of Georgia Press.

Ichikawa M. 2001 « Persisting cultures and contemporary problems among African hunter-gatherers », African Study Monographs, Supplementary Issue 26 : 1-8.

Ichikawa M. 2006 « Problems in the conservation of rainforests in Cameroon », African Study Monographs, Supplementary Issue 33 : 3-20.

Joiris D.V. 1998 La chasse, la chance, le chant : aspects du système rituel des Baka du Cameroun. Bruxelles : Université Libre de Bruxelles, PhD Dissertations.

Joiris D.V. 2003 « The framework of Central African hunter-gatherers and neighbouring societies », African Study Monographs, Supplementary Issue 28 : 57-79.

Kamei N. 2001 « An educational project in the forest : schooling for the Baka children in Cameroon », African Study Monographs, Supplementary Issue 26 : 185-195.

Kitanishi K. 2006 « The impact of cash and commoditization on the Baka hunter-gatherer society in southeastern Cameroon », African Study Monographs, Supplementary Issue 33 : 121-142.

Lancy D.F. 2008 The Anthropology of Childhood : Cherubs, Chattel, Changelings. Cambridge : Cambridge University Press.

Laurance W.F. 2015 « Emerging threats to tropical forest », Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden 100(3) : 159-169.

Leclerc C. 2006 « Le retour de chasse: avènement de la jalousie chez les Baka et dynamique sociale (Cameroun) » (121-132), in I. Siderza, E. Vila & P. Erikson (eds.) La chasse. Pratiques sociales et symboliques. Paris : De Boccard.

Leclerc C. 2012 L’adoption de l’agriculture chez les pygmées Baka du Cameroun, Dynamique sociale et continuité structurale. Versailles : MSH/Quae.

Lenclud G. 2003 « Apprentissage culturel et nature humaine », Terrain 40 : 5-20.

Noss A.J. & Hewlett B.S. 2001 « The contexts of female hunting in Central Africa », American Anthropologist 103(4) : 1024-1040.

Ohmagari K. & Berkes F. 1997 « Transmission of indigenous knowledge and bush skills among the Western James Bay Cree women of Subarctic Canada », Human Ecology 25(2) : 197-222.

Oishi T. & Hayashi K. 2014 « From ritual dance to disco : Change in habitual use of tobacco and alcohol among the Baka hunter-gatherers of southeastern Cameroon », African Study Monographs, Supplementary Issue 47 : 143-163.

Pennec F., Wencelius J., Garine E., Raimond C. & Bohbot H. 2012 FLAME. Free-List. Analysis under Microsoft Excel. Paris : CNRS.

Reyes-García V. 2015 « The values of traditional ecological knowledge » (283-306), in J. Martinez-Alier & R. Muradian (eds.) Handbook of ecological economics. Camberley : Edward Elgar Publishing.

Rogoff B., Moore L., Najafi B., Dexter A., Correa-Chávez M., & Solis J. 2007 « Children’s development of cultural repertoires through participation » (490-515), in J.E. Grusec & P.D. Hasting (eds.) Handbook of socialization. New York : Guilford Press.

Taylor G., Scharlemann J.P.W., Rowcliffe M., Kumpel N., Harfoot M.B.J., Fa J.E., Melisch R., Milner-Gulland E.J., Bhagwat S.A., Abernethy K., Ajonina A.S., Albrechtsen L., Allebone-Webb S., Brown E., Brugiere D., Clark C., Colell M., Cowlishaw G., Crookes D., De Merode E., Dupain J., East T., Edderai D., Elkan P., Gill D., Greengrass E., Hodgkinson C., Ilambu O., Jeanmart P., Juste J., Linder J.M., Macdonald D.W., Noss A.J., Okorie P.U., Okouyi V.J.J., Pailler S., Poulsen J.R., Riddell M., Schleicher J., Schulte-Herbrüggen B., Starkey M., Van Vliet N., Whitham C., Willcox A.S., Wilkie D.S., Wright J.H. & Coad L.M. 2015 « Synthesising bushmeat research effort in West and Central Africa: A new regional database », Biological Conservation 181 : 199-205.

Thompson R.A. 2012 « Changing societies, changing childhood : Studying the impact of globalization on child development », Child Development Perspectives 6(2) : 187-192.

Townsend C. 2015 « Baka ritual flow diverted », Hunter Gatherer Research 1(2) : 197-224.

Vonrueden C., Gurven M. & Kaplan H.S. 2008 « The multiple dimensions of male social status in an Amazonian society », Evolution and Human Behavior 29(6) : 402-415.

Weig D. 2015 « Social change mirrored in Baka dance and movement : Observations from the River Ivindo in Gabon in 2011 », Hunter Gatherer Research 1(1) : 61-83.

Wilkie D.S., Peres C.A. & Cunningham A.A. 2011 « The empty forest revisited », Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1223 : 120-128.

Yasuoka H. 2012 « Fledging agriculturalists ? Rethinking the adoption of cultivation by the Baka hunter-gatherers », African study monographs Supplementary issue 43 : 85-114.

Zarger R.K. 2002 Children’s ethnoecological knowledge : Situated learning and the cultural transmission of subsistence knowledge and skills among Q’eqchi’ Maya. Athens : Wake Forest University.

Zarger R.K. 2010 « Learning the environment » (341–369), in D. Lancy, J. Bock, & S. Gaskins (eds.) The anthropology of learning in childhood. Lanham : AltaMira Press.

Zarger R.K. & Stepp J.R. 2004 « Persistence of botanical knowledge among Tzeltal Maya children », Current Anthropology 45(3) : 413-418.