- Accueil

- N° 7 (2017) / Issue 7 (2017)

- Childhood in Pala’wan Highlands forest, the känakan (Philippines)

Visualisation(s): 14676 (30 ULiège)

Téléchargement(s): 496 (5 ULiège)

Childhood in Pala’wan Highlands forest, the känakan (Philippines)

Document(s) associé(s)

Version PDF originaleRésumé

L’enfance dans la forêt des Hautes-Terres Pala’wan, les känakan (Philippines). Cet article composé de trois parties principales met l’accent sur l’expérience vécue dans la forêt et les valeurs partagées des känakan, un groupe d’âge d’enfants entre 3 et 12 ans, vivant dans une société égalitaire du monde austronésien. Après avoir décrit les activités physiques et cognitives lors de la journée, aux environs des maisons, dans la nature sauvage, au bord de la rivière et dans le champ d’altitude, nous nous concentrons sur les activités cognitives auxquelles les enfants sont exposés durant la nuit. Des extraits de souvenirs d’enfance de trois collaborateurs pala’wan sont inclus. Cet article se termine sur la façon dont les enfants apprennnent de la forêt et de l’école, en langue maternelle.

Abstract

This paper consisting of three main parts, emphasizes the life experience in the forest and the shared values of the känakan, a children’ age group from 3 to 12 years old, in an equalitarian society of the Austronesian world. After describing their daytime physical and cognitive activities in the houses’ surroundings, the wilderness, by the river, and in the upland field, we focus on children’ exposures and cognitive activities at nighttime. Excerpts from the childhood memories of three Pala’wan collaborators are included. Learning from the forest and learning from the school in the mother tongue brings this paper to a close.

Abstracto

La niñez en la selva de las Altas-Tierras de Pala’wan, los känakan (Filipinas). Este artículo está compuesto de tres partes principales, focaliza la experiencia vivida y los valores compartidos de los känakan, un grupo de niños entre 3 y 12 años, que viven en una sociedad iqualitaria del mundo austronesio. Despuès de la descripción de las actividades físicas y cognitivas efectuadas durante el día, alrededor de las casas, en la selva salvaje, a orillas del río, en el campo de altura, nos focalizamos en las actividades cognitivas a las cuales los niños están expuestos durante la noche. Algunos extractos de recuerdos de infancia de tres colaboradores están incluídas. El artículo termina sobre la manera en que los niños aprenden de la selva y de la escuela, en lengua materna.

Table des matières

« Toutes les choses sont des concrétions du milieu et toute perception d’une chose vit d’une communication préalable avec une certaine atmosphère », Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Phénoménologie de la Perception, 1945.

« Dans un milieu humain, la réalité d’une forêt n’est pas seulement écologique, elle est éco-techno-symbolique. Cette réalité n’est ni seulement objective, ni seulement subjective, elle est trajective », Augustin Berque, « Existe-t-il un mode de pensée forestier? »,

Conférence EHESS, 28 janvier 2017.

Introduction

The life world of the känakan1

1In the sub-tropical forest of Nusantara – the Islands in between – we shall focus our attention on the Pala’wan children living in the Highlands of the southern part of Palawan Island, an oblique landbridge on the Sunda Shelf connecting Borneo to the septentrional Luzon (Macdonald 1977, 2007).

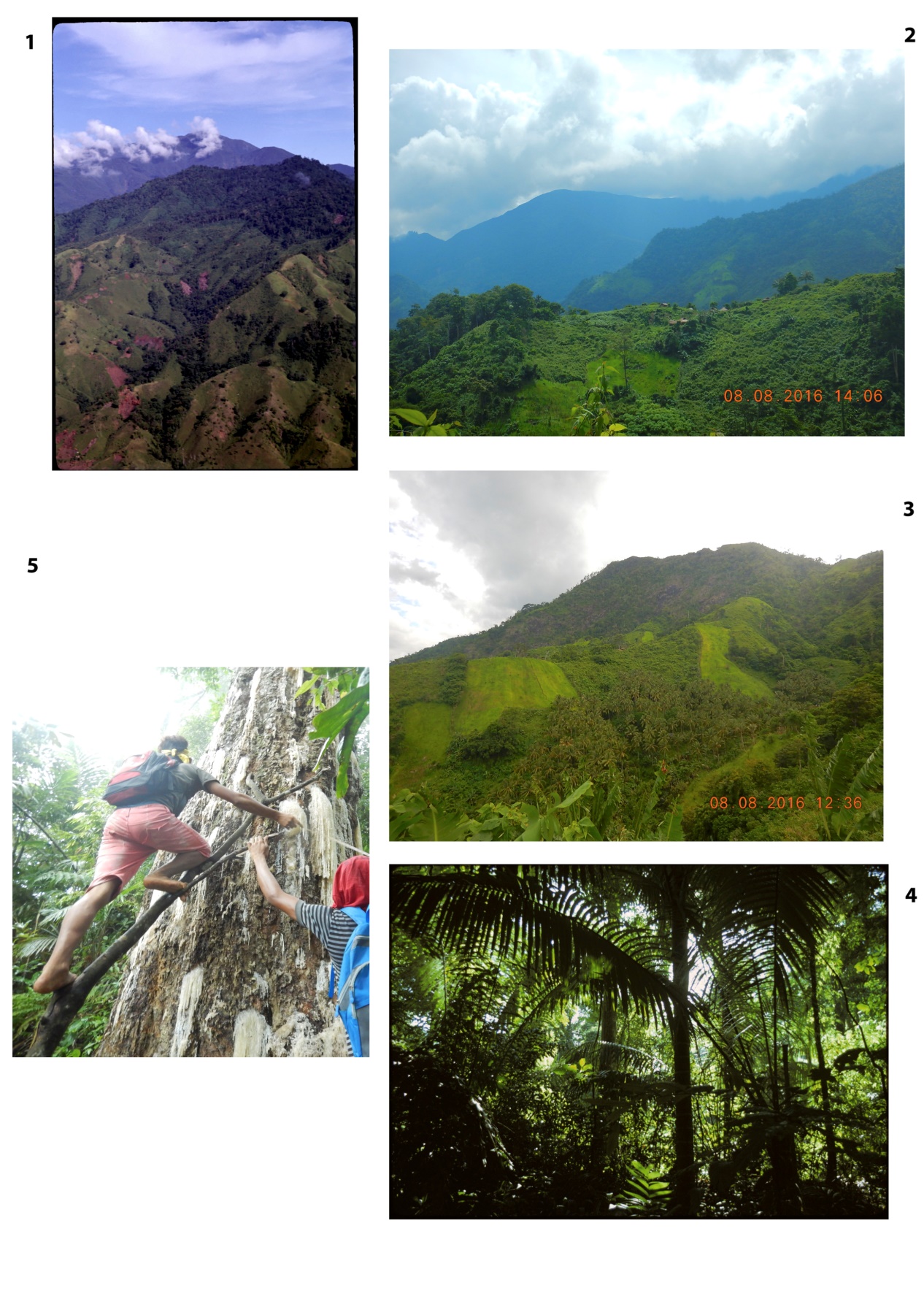

2Steep slopes of mountain ranges and peaks, cliffs, forests and fallows, abrupt trails, and rocky streams, a world of scattered hamlets with small homes made of wood, bamboo, palm leaves or kugun grass (Imperata cylindrica, Poaceae) and a single large meeting house, fragile far away field houses or protective caves and rockshelters of kartsic formations, the world that the känakan perceive and inhabit has physical peculiarities according to the season, dry or humid, altitude, vegetation and rocks formations (cf. Plate 1 below).

3Engulfed in the tiny music of things merging with the musicality of their mother tongue, Pala’wan children are very sensitive to the beauty of sounds and songs of the world they live in. As adults they will keep this playful aural/oral attitude, mimicking the songs of birds, the stridulations of insects and all the sounds of nature by the voice and musical instruments (Revel 2005a, 2005b, 2009).

4Birds and insects are omnipresent and vary from ecosystem to ecosystem. However, in the forest gäbaq everyone hunting with a blowpipe sapukan, is attentive to birds songs for the locating of an potential prey, or for seizing a charming pet ayam and bring it back home hidden in a basket tingkäp to be givento a little girl or a maiden. Enjoyed for a while as a playful toy, the pet will ultimately be roasted and eaten up as a tiny but succulent viand to accompany the staple food käkanän and please the appetite säbläk.

5Mimicking songs of birds, then transposing them into words and music on the mouth harp äruding on the tiny ring flute bäbäräk and on the small lute kusyapiq

Plate 1: Photos of landscape, © Nicole Revel (1972, 1988) and Norlita Colili (2016)

1. Southern Palawan Highlands and Mont Mantalingayan or Käbätangan “Tree trunks”, 1988.

2. The hamlet of Päwpanäw surrounded by fallows bangläy and forest gäbaq, 2016.

3. Large upland field umah, 2016.

4. Lush vegetation of the wilderness talun along the Mäkägwaq River, prior to the December 1975 deluge and landslides, 1972.

5. Gathering resin bägtik on the trunk of an agathis tree (Agathis philippinensis, Araucariaceae) in the high forest of almaciga käbägtikan, 2016.

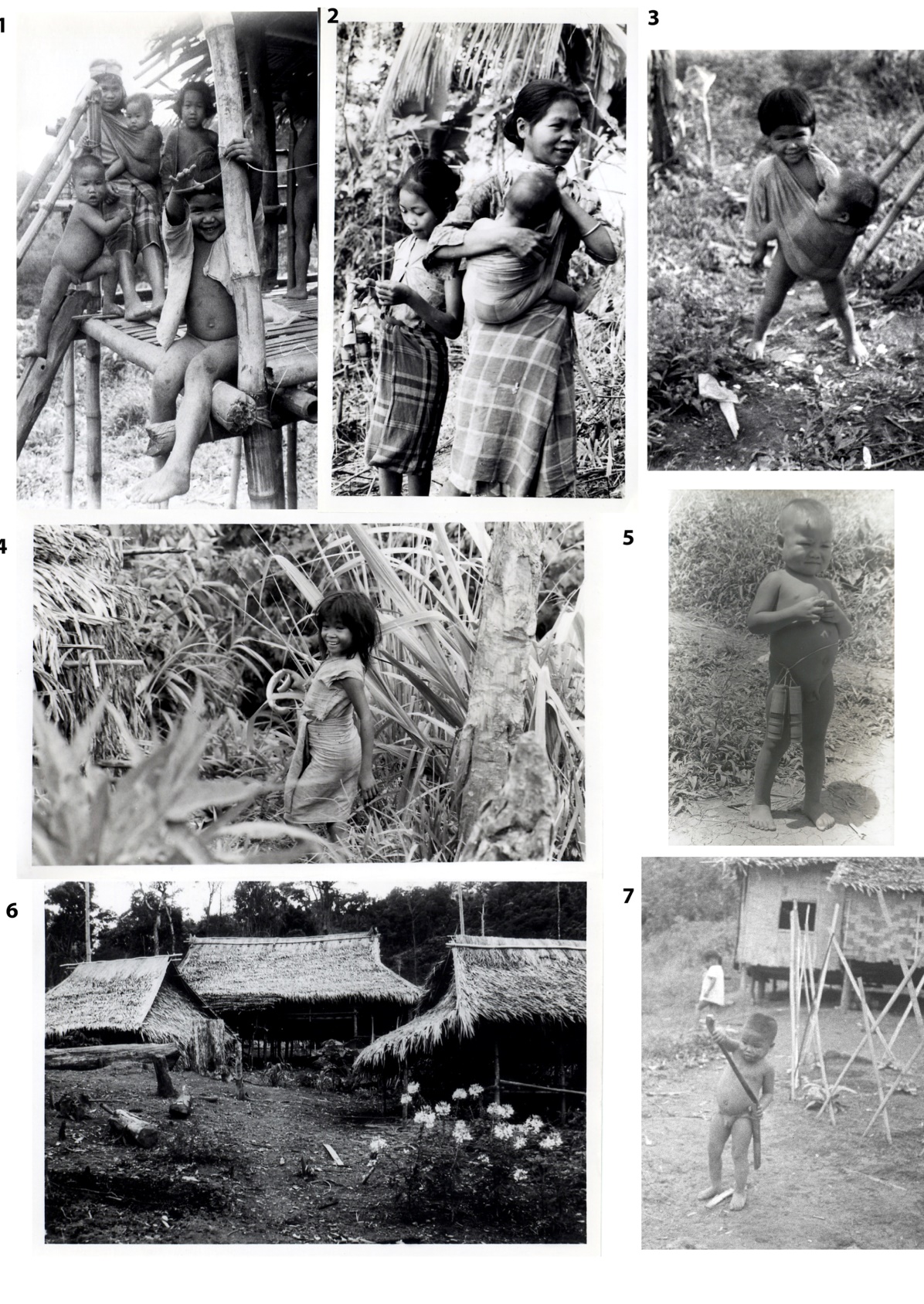

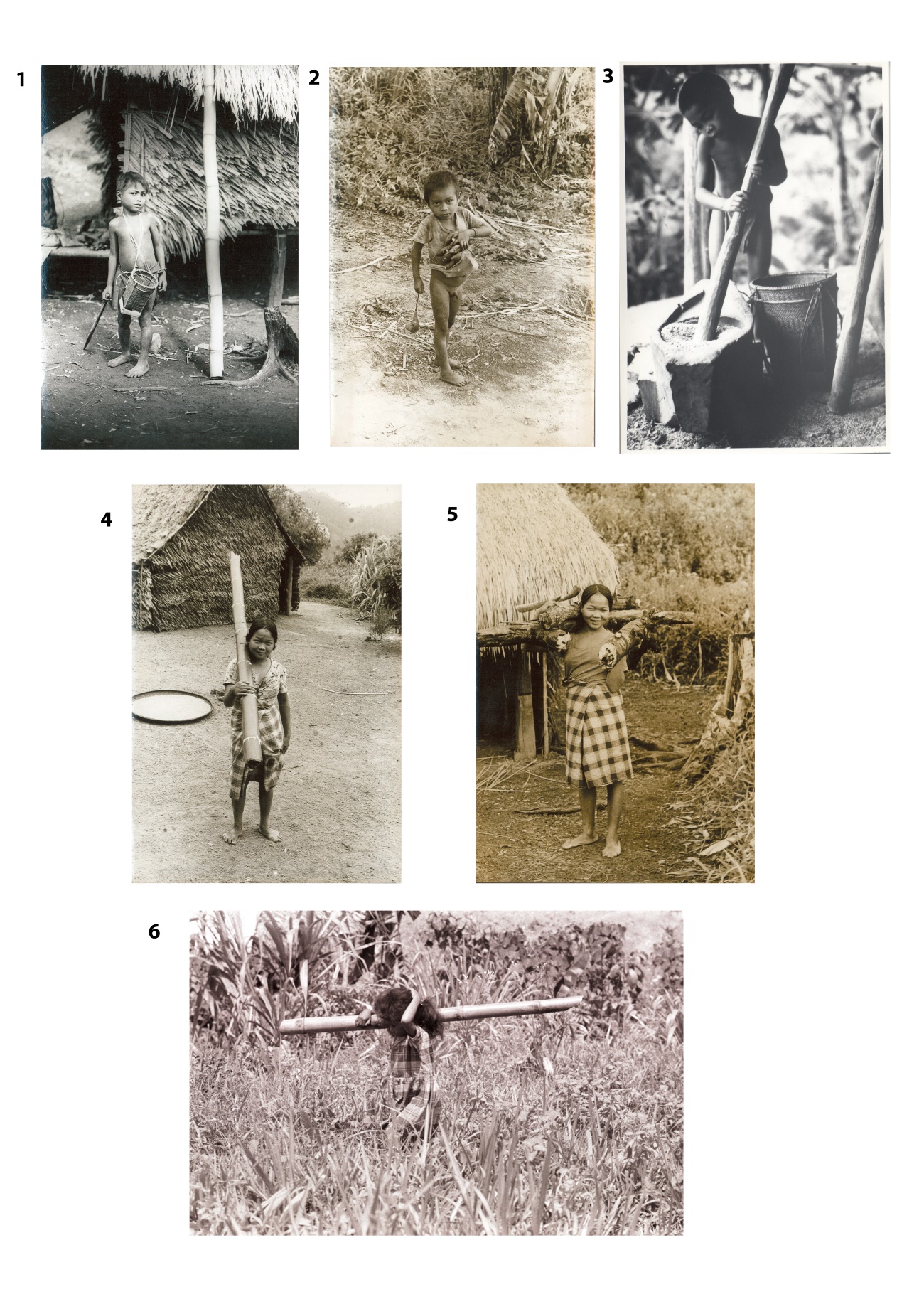

Plate 2: känakan in the house’ surroundings lägwas,

© Nicole Revel (1972) and Charles Macdonald (1972)

1. Luning, Suning, Miryun, children of Lambung and Ränting, 1972.

2. A young girl always accompanies her mother as she goes to visit another hamlet, 1972.

3. Little Luning takes care of her baby sister as the mother went to weed the upland field, 1972.

4. On the way to the river crossing the wilderness talun, 1972.

5. Miryung took his father’s tobacco container aläp and wears it, 1972.

6. Pinigisan, a hamlet with houses close to the large meeting house kälang bänwa, 1972.

7. Miryung, less than 3 years old, is handling his father’s machete tukäw, 1972.

6tuned to läpläp bägit2, part of every day’s entertainment. In the Highlands, this music brings luck and is considered a good omen for hunting. It can be played by men, with a tiny vignette teaching the känakan aboutthe bad biting centipede älupiyan, for instance, its fast way to move and aggress humans, provoking laughter and memorable teaching. The lute may be played as a contemplative moment in daytime or at night by a young maiden or by a young father lying in a restful posture with his wife and their newly born baby, close to her as they are on the verge of sleep on a platform in a cave of the Singnapan valley.

7The ostinati of insects accompany everyone’s sleep, and from daybreak following the intensity of the ascendance then descendance of the sun, function as a clock; meanwhile in daily life, the flights and songs of birds are omens ngasa, for adults and can prevent them from moving. But children do not care about this yet, they enjoy the tiny music of things and love to learn how to play mouth harps, flutes and lutes.

Daytime physical activities and cognitive activities in the houses’ surroundings lägwas, the wilderness talun, the fallow land bängläy and by the river danum

Playful children in the lägwas, the houses’ surroundings

8A hamlet rurungan is inhabited by a group of sisters and first cousins assimilated to classificatory sisters, around which men – following the rule of uxorilocality – come and aggregate mämikit as husbands. This local group is under the protection and control of a father who is also the local headman. So the children are in fact first cousins assimilated to brothers and sisters, a group of siblings känakan, making the age group 1.

9In a hamlet of five to ten homes, the houses’ surroundings lägwas together with the kälang bänwa the nearbylarge meeting house, are an extension of each family home bänwa (cf. Plate 2 above).This open sky, clear and cleaned space, is the children’s playground where kites taguriq can be made and flown, andtops kasing, can be thrown when the soil is dry as hot seasonlight winds blow.

10Everyday objects and tools are all accesible to all of the children:open basket tabig,basket with a covert tingkäp, winnower nigu, as well as men’s bolo knife tukäw, women’s curved knife paqis and palm leaves; left over gahid or buldung leaves and cleaned stems. Nothing is forbiddento the touch or to handling which allows children to develop dexterity and awareness of sharpness at quite an early age, as no one interferes to prevent them to discover (cf. Video 1 and 2 below).

Video 1: Children handling a machete tukäw or a short blade tibig (length 49”), © Hermine Xhauflair, 2017

11https://youtu.be/AFeT7hCw4ug

Video 2: A girl playing with a small curved knife (length 65”), © Hermine Xhauflair, 2017

12https://youtu.be/kIa0h44IJZI

13In this place, the little ones can play together in the shade of a large jackfruit tree, or the shaded place sirung, below the floor of the large meeting house. However in this place too, little girls of 3, 4 or 5 years old might have to take care of their younger brother or sister for half a day, while their mother is weeding or harvesting rice in a distant upland field. This is a long-lasting effort and responsibility for the little girls who have been abruptly separated from the mother’s tender contact by this newly born infant mämäläk who is never left alone. They have to behave as little guardians, silently swingging the baby from one leg to the other, a heavy load on their hips, mimicking the postures of the mothers and fathers (cf. Plate 3 below).

Children foraging in the wilderness päri ät talun and catching in the river päri ät danum

Danum, the river

14The river danum is a playful place of resources and activities (Revel 1990-92).Fishing with hook and line tiny river fishes – ägtaq, bäribi, mängangaluyäw, barubuk, usap, kämaq kälämuq (Gobiidae) and mätaqan, dämagan, pigak, lugusan, päqit, ulpis (Cyprinidae) – is a pleasant activity carried out by women along with the children.

15When they grow up and become more independent as känakan – from 6 or 7 to 12 years old –they go and fish together by the river side catching by hand land crabs – raramu käyängät, lämläm, tamuk, tingting suwat – and fresh water shrimps – urang, urang dängawan, sirsyar, ipun, päyärak, lampung, ämämsäy –as well as fresh water crabs– käyängät, käyängät mäqitäm, lämläm, tamuk, käräpäy, tingting, tingting suwatRevel 1990-92) — river snails– susu–uyäw, susuq balud, täkukang, tätangi, damisil. All this is a delight and shall be cooked and shared on the spot. But there are also bigger snails in the forest –patung balay, patung kälaq, patung buku, patung

Plate 3: känakan helping in daily life tasks,

© Anna Fer (1981) and Nicole Revel (1972)

1. Going to the field to gather tubers with mother and aunties.

2. Back from the field with a load of tubers.

3. A young boy helps his mother pounding rice with a heavy pestle lalu.

4. A young girl is back home carrying the bamboo container heavily loaded with water.

5. Back home from a fallow carrying wood for fire.

6. Going to a water well carrying an empty bamboo with double internode sagäb, 1972.

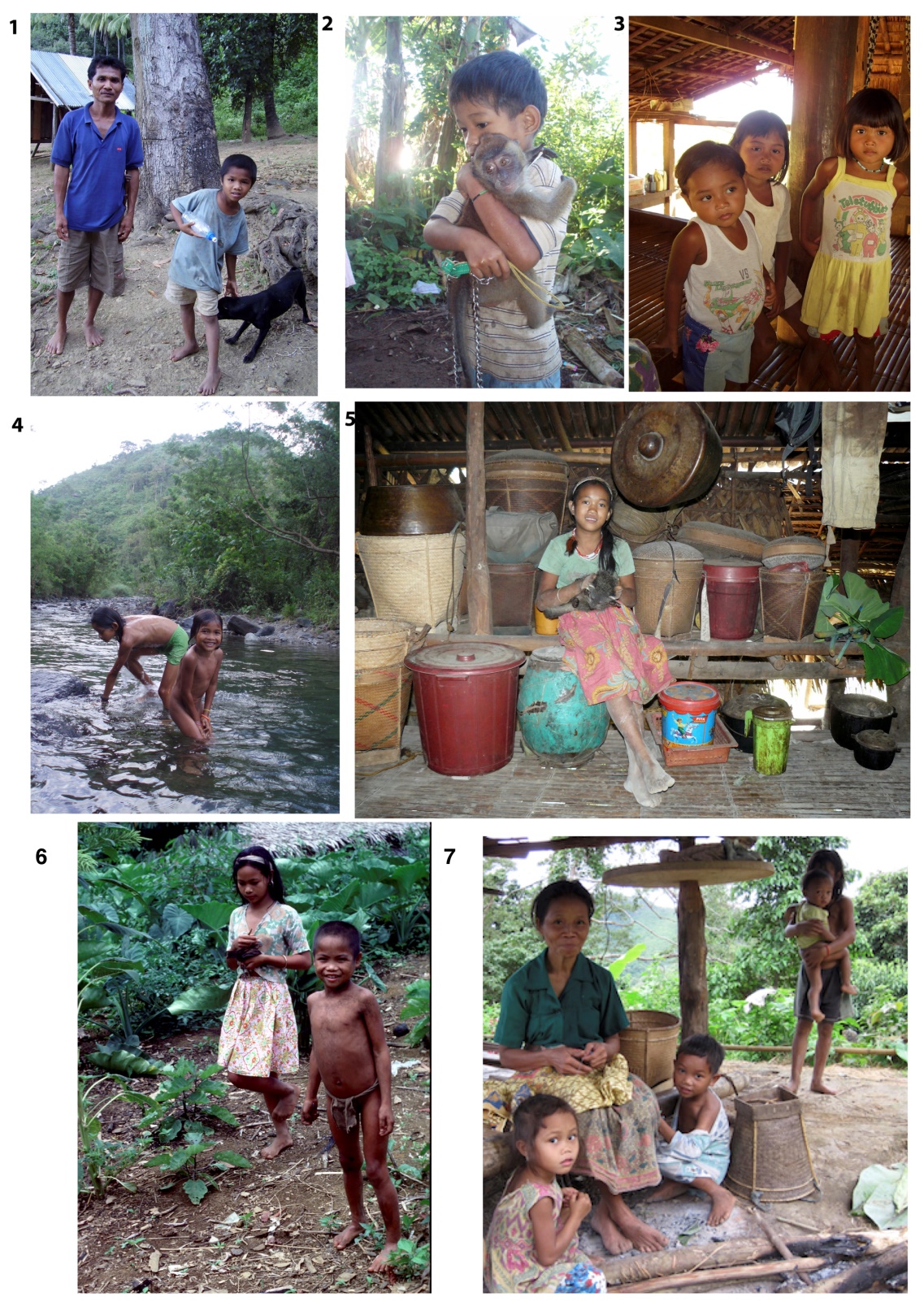

Plate 4: Känakan leisure and pets ayam,

© Nicole Revel, Charles Macdonald, Hermine Xhauflair, and Norlita Colili

1. Linggit and his son on their way from Tabud to Mäkägwaq, the dog comes along, 2011.

2. Abraham and his pet monkey amuq, Malia, 2011.

3. Three cousins in the kälang bänwa of Apäl, their grandfather, 2006.

4. Enjoying a bath and water games, Mäkägwaq River, 2011.

5. Burnay and her pet, a baby bear cat manturun, Tigaplan Hights, 2013.

6. As a young maiden already, Rusi is caressing her pet bird, Amräng, 1981.

7. At the shelter of a rice granary lagkäw, children and grandmother spend some leisure time, upland of Amas, 2016.

16lintang, patung ratrat, patung dändän, patung däbah –that arecollected by their mothers or fathers, to accompany a meal of the day.

17There are ten kinds of river frogs known. Nevertheless the Pala’wan avoid eating frogs, for they consider them disgusting as an accompaniement to the stapple. This food taboo could be a means of protecting the children – and later on the adults – from eating poisonous toads when they drink.

18As they grow and become stronger, children make dams in the riverbed, placing fishtraps bubu, snorkling, catching crabs, then cooking the preys they were able to catch on the river banks in a tiny can they have brought along. When older, they are able to catch eels – indäräg, amayu, säka-säka, rurung (Revel 1990-92).

19As they enjoy collecting these catches from the wilderness päri ät talun or from the river päri ät danum, they eat them on the spot, and then, they acquire a major complement in proteines to the daily food given by the adults at home, twice a day.

20A tale that serves as prelude to the epic of “Kudaman” reminds them of the story of the two girl cousinswho, at the request of the headman Pänglimaq, went to the river to gather water shrimps urang. Tuwang Putliq, seeing a golden shrimp, is irresistibly attracted to a water pool libtung and refuses to return home. As she takes risks and disobeys, she is captured by the Leader of Crocodiles Pägibutän ät Bwaya and finally will be saved and revived thanks to the mediation of the Young Man of Cumulus Clouds Känakan ät Inarak who will be able to retrieve her little finger nail from the last tooth of the Oldest Crocodile… (Revel 2017b: 15.10).

21There are many water games as children and maidens in circle splash rhythmically the water surface of a pool and the sound tuligbwäng isaccompanied by loud laughter, a moment of shared joy (cf. Plate 4 above).

22As days are spent playing together, they elect a friend and then they go two by two, hands in hands, arms around each other, picking fruits of vines and trees in the forest, gleaning and eating them, other delicious snacks to enjoy and share on the spot. This provides yet another great dietary intake of vegetal proteines and vitamines.

23Foraging mushrooms (Revel 1990-92) and land snails – patung balay, patung kälaq, patung linsa –along the way is also experienced as a playful catch päri patung by women and children. This is first a playful transmission of know-how from adults to small children, who quickly manage to catch them.

24When they reach the age of 7 or 8, they will be given various training by adults. Then girls will follow their mothers and boys their fathers. This is their first experience of the division of labor. As Antonita saw a plant on the trail, she told her daughter, “This is a female and it has a male sibling”. With these words, mothers are starting to teach their daughters, by observation and association, a fundamental binary principle organizing the plant world within a classification relating them also as males and female siblings mägtipusäd or as companions mägiba, a reflection of the social organisation actually lived by the children.

Bängläy, the secondary growth, the fallow

25After two years, the field is abandoned and the vegetation takes over. In a span of twelve years, the higlanders distinguish four types of fallows, places of foraging and gathering mushrooms, bamboo shoots, and useful plants for crafts. Various bamboos and all kinds of palms and vines gahid to weave baskets tingkäp, tabig, winnowers nigu are gathered.

26Boys can make bird traps litag, mouth harps äruding andlures pispis; kites taguriq and whirligids while young bachelors subu sculpt bracelets luyang made of mantalinäw wood, tiny birds bätbägit, and pigs bikbyäk, for offerings, handles of machete tukäw with elegant umbalad, quiver kärbang, and a tobacco sets aläp.

27Norlita Colili’s memories, in her own words (cf. Video 3 below):

28During summertime, the surroundings are a bit dry and good for an easy harvesting of mature raw materials used to weave baskets. Before midday, after working at the upland field uma, my mother would drop at a nearby place where bamboos sumbiling were abundant, to collect a bundle of around 5 to 10 poles, which she will use for weaving nigu, the large winnower.

29After eating lunch, she would split the sumbiling she had collected, with a machete tukäw, a truncated machete bäkuku and split the bamboo into small slats and shave it with her curved knife päqis. To do this, we need to sit comfortably and safely in a corner so the materials will be kept clean and intact until the winnower is made. The weaving place should be a stable platform or bamboo floor, with a good light, to facilitate the making of a quality woven nigu without stressing ourselves out for sitting long hours and our eyes keenly fixed on the weaving … (Norlita Colili, Mänkungän, 2016, see also Colili & Andaya 2008).

Video 3: Passive learning: trimming bamboo to make strips for basketry (length 69”),

© Hermine Xhauflair, 2017

30https://youtu.be/iQFzfhBrhGY

31Girls helping to fetch wood, helping to fetch water at the near by stream saqsapaq or shallow well, accompany their mother and aunties who will carry the single or double bamboo internode päyaqung, sagä on one shoulder and follow the happy call to join (cf. Plate 5 below).

Plate 5: känakan foraging,

© Hermine Xhauflair, (2011)

1. After following an adult man in the fallow bängläy, a 7-year old boy is gathering the remaining part of a palm cabbage to eat it raw, as a snack. The tree bätbat (Arenga undulatifolia, Arecaceae) had been previously opened by the man who took the main part of the cabbage to bring it back to the hamlet and cook it. Near Ämrang, 2011.

2. A boy of about 10 years old is cutting branches of binuwäq (Macaranga tanarius, Euphorbiaceae), whose sap is used as a glue. This has been requested by his mother who needs it to fix the sheath of a machete tukäw. Ämrang, 2011.

3. A 7-year old girl, Angeline, alias Layla, carries a bundle of rahaq leaves (Pandanus sp., Pandanaceae) with a string around her neck. She has been accompanying her father and one of his friends high in the forest to gather these leaves, used to roll cigarette. About 1 hour away from Malia, 2011.

4. The same girl is holding a crab that she caught in the river near the hamlet during the day, while adults are away from home working in the field or foraging in the forest. Malia, 2011.

5. and 6. A crab is being cooked by Abraham, 5 years old, in the hearth underneath the large meeting house. Malia, 2011.

7. Marisa, 4 years old, eating a snail she just caught and cooked in warm ashes. Malia, 2011.

8. A 11 to 12-year old girl, making a digging stick out of a stem of manioc kumbahan (Manihot esculenta, Euphorbiaceae). Ämrang, 2011.

9. Then she is using it to dig a wild tuber out of the ground. Ämrang, 2011.

Gäbaq, the secondary forest

32Gäbaq is composed of four types of secondary forest that are places of fun in hunting with small blowpipes sapukan, and foraging. Children are also fond of eating the larvas of bees, of palm weevil linggawung andthey love to eat raw, grilled or boiled insects, like winged termites anäy. Animal proteins of insects, larvas, fresh water crabs and shrimps as well as little birds are part of a healthy complementary diet.

33As young känakan, they do not venture too far by themselves. However when they reach the age of 7 or 8 their father can take them along in the forest to capture rodents and squirrels as described here by Jose Rilla.

34Jose Rilla’s memories, in his own words3:

35I was probably around 8, I think. As I was of age, my father started to make snares with various loops rabay. When my father was laying snares, he would take me along to the forest. We were able to catch wild cocks and hens and a rooster. Every three days we were going to look at the snare. We captured also a dove limukän, with the litag trap. I only look at the way the snare with loops is made. He was doing everything, I was just looking, I was observing how the snare was made. For a rooster, the height of the loop is different: it is a finger long, as we say. For a limukän, it is lower, one phalanx for the height of the loop. First, he taught me how to make the strings. He taught me more than four types of snares and how to attract the game to the trap.

36Then, one day he told me ‘Tomorrow, you will go and check by yourself, together with your two younger sisters, Luhan and Gibang, you will go together, they are still small’. It was not far away as there was a lot of forest before, the forest gäbaq was thick near by our home at Sukswak. As we went, 8 doves were trapped! I am quite happy and I twist their necks one after the other. When dead, I unfold the strings, I tie them up all together and give them to Luhan to carry. Once again I fix down the snare. On our way back home, I was bitten by a centipede alupyan, I cried and did not eat the doves, only they could eat the doves… during four days I did not eat any rice or dove as it was very painful and no one knew how to cure this bite… I had to bear the pain. After four days, I felt better and I knew how to lay traps.

37‘Let us go and lay two traps, one for a squirrel and another one for the civet so that you know how to fix baqang for the civet masäk and one for the bear cat manturun’.

38I just observe the fixing of the traps in the forest. ‘Here is a palm tree bätbat[Arenga undulatifolia, Arecaceae], its fruit is the food of the civet, let us fix the trap the two of us. Climb, remove the leaves, so that there is no way to escape by the top’. Once I had removed the leaves, he fixed the trap half way on the trunk of the palm tree ‘This is a trap for masäk’ and further we fixed another one, a trap for the bear cat… For it, another measurement is necessary and a long propeller. This is how I learnt how to make and lay snares and I started to lay snares by myself.

39After my father’s death, my mother, who was expecting Sianu, returned to her father’s home Uduk who helped to deliver her and I do all the work, up to the time Sianu was grown enough. I was 14 when my mother married again Galnu. After this, I considered him as my father and I was following him as we had someone to look for food, because our field was not big and my mother was searching for wild yams bagid in the ground, we had to bear with hunger urap. He knew how to hunt with blowpipe sapukan, he also knew how to forage all kinds of food in the wilderness talun. He was a Highlander, a Taw ät Dayaq, from the Tämlang River. As a wild boar was captured, they had to make an agreement on the catch: what is to be shared, what is not.

40Then, for the first time, I could listen to a discussion on how to share the preys captured in the forest bisara ät pägbagi, Panglimaq Dani said ‘If you happen to catch a boar, you shall not stay away, on the contrary, we shall continue to share. We are present or not, we shall share half and half, as we are nor yet really far away. That is an agreement. If you really move far away, we shall modify our agreement, we shall no longer share. But as you are not too far, let us not change our agreement, let us keep on sharing…’ (José Rilla, Tataran Island, 1995)

41Mäsinu Intaräy’s memories, in his own words (cf. Video 4 below):

42First, I did not know how to hunt. My father made a blowpipe for me. When the dry season arrived and I came of age (by 7-8 years old) my father said to me: ‘Come let’s go and hunt with the blowpipe’. He did not teach me anything else… Then I learnt how to hunt with it. They taught me hunting with the blowpipe as a game. I learnt nothing else except to set all kind of traps, snares, traps in trees for small rodents, and big traps in the ground bawäg for the boars. In the river, I also learnt to set fish trap bubung and to make dams by moving stones… (Mäsinu Intaräy, Tataran Island, 1995)

Video 4: A boy making a small blowpipe sapukan to play with (length 73”),

© Hermine Xhauflair, 2017

43https://youtu.be/rsm6pmrf2tc

44As they search for birds and small rodents, as well as insects, plants, and fishes and any other prey, the känakan accumulate many sensations, observations and memories about the natural objects. Being attentive and sensitive to the forest’s soundscapes, colors, smells, odors and fragrances, contacts and touch (lights, winds, rains, water, soils, barks, thorns, leaves, vines, ferns, flowers, feathers, furs, etc) they discover and internalize the living world.

45Their respective imagination is stimulated by their personally lived experiences and the intermingling of memories and imagination is going to vary according to each one of them.However as a group, they share the same world – the given empirical world they inhabit – but when according to their parents, they reached the age of reason at 7 or 8, they already have imaginative variations, a deep layer of their respective consciousness, their subjectivity.

46However, gäbaq is also a risky place. The danger of getting lost and being attracted by a female Demon Kukuk, or Oger Bungäw, living in cliffs and chasms, is there. These abrupt stones and lonely formations are scary places and short tales are warning the children to avoid the attractive Evil Doers, or bumping into a Malevolent Taw Märaqat. The fear of meeting the ghost of a dead relative Mämangut, as well as passing by a large ficus tree baliti, the denof Evil Doers Langgam or Saqitan, are conveyed to them by adults and have a strong impact on their imagination kira-kira. This is how some components of the adult worldview are instilled early on the känakan.

Rupaq, the primary forest

47The primary forest rupaq with, agathis trees käbägtikan – bägtik: Agathis damara or Agathis philippinensis, Araucariaceae – and huge trees ginuqu (Koompassia excelsa, Fabaceae)and dipanga (Pometia pinnata, Sapindaceae) is filled with tall trees, which aside from shade provide many resources to the ones who know how to use them:

48- änuling (Pisonia umbellifera, Nyctaginaceae), whose bark can cure centepede bites and whose fruits can be turned into sticky traps to catch birds;

49- kämilit (Alstonia scholaris, Apocynaceae), whose exhudate cures wounds;

50- kayayansäng (Albizia acle, Fabaceae), whose bark is a medicine for flu;

51- lipsä (Aglaia sp., Meliaceae), a tree whose beautiful red flowers grow from the trunk, hanging down with gravity like as many bead necklaces. In the dry season its acidic fruits are ripe, ready to be enjoyed during a trip in the forest;

52- mälaga (Wendlandia philippinensis, Rubiaceae), whose strong wood is the raw material of house posts and the flowers will be sucked by the bees a converted into a delicious honey;

53- saläng (Canarium asperum, Burseraceae), whose fragrant resin makes long lasting torches to enlighten a family or a meeting house during the night;

54- säramirig (Bischofia javanica, Phyllanthaceae), and täwläy (Cryptocarya sp., Lauraceae), which also have medicinal properties and can help to relieve a stomach-ache (Xhauflair et al. 2017).

55The canopy is much too high to reach, get the flowers and suck the nectar. But sometimes the känakan can enjoy this kind of kendi together with honey dägäs gathered by adults and young bachelors subur.

56Then by the age of 13, they start to go with adult men to gather almaciga resin bägtik and will discover the beauty of the old growth forest as the young strong adults will make a kibah to carry heavy loads of cristal resin (50kg) to the lowlands bodega. Since a long time, this raw material used to make lacquers is bringing back some cash money to the Highlanders.

57Monsoon breaks in June4, while in August winds and rains become quite strong and rice harvest starts.Caves and rockshelters singläd in the kartsic formations on the East coast of the Rangsang Valley and particularly the Singnapan Valley, have been selected by their great grandparents, a safer place for a family to take shelter, to live in and be protected from the loud and feared bursts of thunder duldug. For when Grandfather Thunder Upuq Kuyäw speaks, he expresses the ire of Ämpuq, the Master of all, and the genuine human beings taw banar are afraid.

58For the Pala’wan this is a seasonal variation of habitat during, the long lasting monsoon season barat that can last five months or more. However, these are pleasant times, “You can live protected from floods, winds and heavy rains, and by doing so you are protected from fevers”, said Isnig5. It is also a sort of holidays – for elders and youngsters – as they enjoy fishing and foraging a great variety of foods from the river bed and the surrounding forest, together with their respective mother, and mother’s sister’s family, their first cousins, together with their grandmother. Collective fishing by beating tuba (Derris elliptica, Fabaceae), a root gathered in the forest, making pools with stones in the river bed is used to put the fishes to sleep. Then the small group will enjoy collecting them with a small net syud. All this foraging is lived with a cheerful excitement and laughters, mainly at night with a torch, in the underground river: “In the caves, we can catch many kinds of viands – kurikit, bägit-bägit, käsiliq – and eels.”

59At dusk, in search for ripened fruits on the main land, bats kabä, used to fly out of the caves by the thousands and it was one of the abundant catch of the day. At the mouth of the cave, aman isstanding ona platform, sweeping the fruit batswith a long pole on top of which a bundle of thorny rattan had been tied up. He can sometimes alternate with his wife below to gather the preys and roast them with their fur. Another catch is by knocking down the swiflets sarang with a largeoblong racket kärikid as they fly out of the cave. Nowadays, after the temporary inhabitants had fixed fishing nets along the galeries in order to capture more bats and swallows, birds and mammals have abandonned various caves occupied by the Pala’wan (Vallombreuse 2017).

Uma, the upland field

60The upland field uma is a place of work and ressources for the känakan to protect from birdspests, monkeys and wild boars. As the paddy is ripening, two young cousins-friends are in charge of chasing away flocks of maya birds – dignäs, dignäs märägang, karawit, kandulung – with whirligigs and musical bows, while sparecrows have been made by adults and erected in the middle of the field.

61It is also a place of work and constraints as children are helping their mothers and aunties gathering tubers in the field of one of them, bringing back home this food in order to share it on the floor of the large meeting house, according to the custom of sharing food between sisters Adat ät pägbagi.

62When the season of felling trees pänambang starts, the men have to face strenuous physical labor according to the custom of mutual help and assistance Adat ät tabang. They walk in a row to open the new far away field, playing gongs basal on the blades of their machete while the handle close to their open mouth turns into a box of resonance. Then, to imitate the adults, the känakan are playing basal on machetes and cooking pots coverts basal ät takäp ät kandiru.This music sounds as a joyful reminiscence, transfiguring the hardships of the labor by alluding to the mythic time when life was light and pleasant, when tools did the work alone in the field and giving birth was not a painful labor. This leisure was jeopardized when a scatter brained girl transgressed a prohibition by peering at the tools as they were working alone, then the happy leisured life of human kind was for ever destroyed.

63Mäsinu Intaräy’s memories, in his own words:

64My father also taught me how to make the field uma to clear mängririk it. So that you won’t have a hard life, you must know how to plant cuttings and all the tubers You must know how to slash then burn the vegetation and grow rice in association with tubers. First, I planted cuttings of banana trees and sugar canes in a small field, I love bananas! Then later, when I was grown up, he taught me how to build a rice granary lagkäw. Without a granary you cannot store the paddy… (Mäsinu Intaräy, Tataran Island, 1995)

65Jose Rilla’s memories, in his own words:

66Then I am grown up, I am 10 years old. I was doing my field already but it was a small one, my seedlings were only 3 cans of Nestlé® condense milk… But I was weeding with application and my father used to say ‘It is necessary to weed so that your paddy rice shall grow bountiful’ and I was cleaning my field and my rice was beautiful. This was my sole work, year after year. As the slashing season pängririk was coming, I was the one to cut the vegetation, my father could not anymore. He had a strong back pain after he fell from the top of the house… (Jose Rilla, Tataran Island, 1995)

67As daylight fades out and shadows enter the night, mothers say: “Don’t be noisy!” kas käw kägibäk – This is one of the few injunctions, one can hear, to protect the children from Evil Doers who are roaming around in the forest and might come closer to the hamlet and to the lägwas at night, threatening the whole group of neighbours säng kärurungan.

Children’s exposures and cognitive activities at nighttime

68At dusk, by 6:15 pm, the känakan have an early frugal diner with their respective parents; then they are going to become active as an age group, in another way. Like birds, they become silent as the couple rests on the main floor of the large house to go to sleep, little boys lying down on their father’s side and little girls on their mother side.

Enjoying the sounds of the mother tongue, discovering meaning, playing with words

69As obscurity engulfs the fields, the forest, the river, hamlets, and houses, another type of cognitive activity tends to prevail. While lying down on the lateral plateforms särimbar, children are resting, but they keep on hearing, on listening to the adults’ speech sugid. This is the time when they develop their imagination kira-kira and memory randäm. Playing with words and storytelling complement their experiences and memories of the day. And so, before sleep takes over, adults and children can enjoy making riddles igum (Revel 2017a6).

70“The riddle of grandfather starts:

71They are five brothers

72of various lengths.

73What is it?

74 It’s the hand.”

75They enjoy listening to short stories and to their teachings. It is an informal and playful moment to be immersed in the language and the worldviews of adults, to internalize the sayings of the elders and their values.

76Storytelling does not occur every night in every home and so the little flock of children can decide to sleep in the house of their choice, near another close anty, wherever there is something happenening, something entertaining such as a visitor staying overnight.

77They enjoy listening to hilarious stories, such as “Water shrimp and Quail” Urang bäkäq Puguq about the manners of birds bägit, of insects räramu and agressive animals sätwaand the eventual encounter in the forest trails with the voracious Kukuk and Oger Bungäw. Also they love to listen to long tales sudsugid, teaching the Adat, the right behavior to follow, as it should be practised in the adults’ world, namely mutual help tabang, obligation to share bagi, compassion ingasiq, as well as parity in an Exchange, gantiq.

78However, one of the känakan can also suddenly take the unforeseen initiative to move them all to the house of the lonely anthropologist to keep her company and entertain her staying over night and telling her audacious stories.

79When a visitor passes by and is invited by the pänglimaq to spend over the night, if he happens to be a singer of tales mänunultul they all join the adults under the roof of the kälang bänwa and listen to an epic tultul. A long narrativecan be sung by someone in the hamletto welcome the visitor with courtesy, or the latter might be invited to sing a tultul from the far away valley he is coming from.

80All night long, the känakan will follow the story, falling asleep from time to time, and waking up as the plot keeps unfolding until the first rays of the sun demand that the singer of tales bring the story to a close. These beautiful nights are very exciting for the childrenas there is always an attack by Ilanän pirates, intense pursuit and fight, with lots of magic spells, a shamanic “voyage”, a self controlled hero and his calm lovely wives. These nights of a long sung narrative performance are a crucial moment for a silent attentive child, the very beginnings of a poetically inclined and dedicated life, the very first embodiement of a sung narrative by a young singer of tales (Revel 2017b).

81Memories of Mäsinu Intaräy – a singer of tales who became National Living Treasure – in his own words:

82I saw the capture of a wild boar, we were delighted because we had a good viand for our rice. Every time a boar was caught in the pig trap bawäg or by men with spears and dogs, someone sang a tultul while its haunch was being roasted on a bamboo shelf made at dusk. My grandfather used to sing a tultul and it lasted the whole night, until sunrise. The grown-ups did not sleep. Nor did I. I wanted to listen. I loved it for there were fights, and the story was beautiful. I thought it was a good story and deep inside, I knew everything. Until the next morning, I did not sleep. And from then on, little by little, I increased my knowledge of sung narratives. I could not yet sing the story myself, but we used to play games around the houses and all day long, the tultul was singing in my head. I imitated the tultul of the grown-ups deep within myself, I did not sing yet myself… (Mäsinu Intaräy, Tataran Island, 1995)

83A similar inclination to the beauty of the spoken words and argumentation can develop as the känakan listen to the long jural discussions bisara conducted by the eldest playing the judge ukum, in the kälang bänwa, listening to the rhetorical talks of the respective litigants and their spokemen mämimisara while the neighbourhood – men, followed by their dog, women carrying along babies and children – listen on as witnesses.

84One of the känakan might also develop an aptitude to remember the cases and the related fines and the offerings, as he followed silently but faithfully his father. Such is the case of Jose Rilla who became a famous judge in the Mäkägwaq and Tämlang Valleys (Revel 1980, 1990-92, 2017a7) as well as Mäsinu who, as a child, used to bring the betel quid box sälapaq to the spokemen and quietly listen to the long lasting debates conducted by his father and relatives. From childhood, a familiarity with this sophisticated verbal art is acquired, and an inclination for rhetorics may develop.

85Jose Rilla memories, in his own words:

86In Mägkabuk, there were jural discussion bisara and I always accompanied my father. He would take me along, wherever the bisara was taking place. Seated by his side, I was attentively listening how the discussion between the two parties was conducted.

87First, I attended the mariage discussion of Panu and my older sister. The present of engagement pakirim was discussed. I knew all the moves and deals for a procedure with päkirim. At this level, I am only listening, but I keep on memorizing how a discussion unfolds.

88For adultery, as well as robbery cases, I am still present, listening. However I do not speak yet. I only listen. If the jural discussion continues at night, although I am lying down, I do not sleep. I listen carefully to all their doings.

89When I was around 12, my father became very sick and could not walk anymore. This is when he died… (Jose Rilla, Tataran Island, 1995)

90At night time, as adolescents, young bachelors subur would play mimicking the elders, acting as mediators under the guidance of the Eldest Mägurang who would distribute them in two parties, so the simili bisara could be performed.

91As adults, in order to be recognized and appreciated in this verbal ritual, they would have to memorize the numerous cases of Adat, the system of fines bätang or murta, the system of offerings ungsud and to master the code of social values the law Saraq, of this oral traditon. Such a knowledge and mastery käpandayan are built up, little by little, from childhood.

Sentiments and emotions

92During the night, they might be awakened by a mother giving birth and all the noises related to this event. They are not prevented from being there; these events are part of life in the household and children are not cut off from them.

93When a baby boy emerges from the mother’s womb, one can hear “outside” liwan, and when it is a baby girl “inside” säläd. This is a way to contrast the two sexes by orienting the future of each one in the alliance of marriage: boys have to leave their parents’ home and aggregate to their new affines in another hamlet. Girls, together with all their classificatory sisters, have to stay in the hamlet and live close to their parents, under the custody and protection of their father or their uncle. This polarity is linked to the prohibition of incest: a young boy cannot marry a first cousin with whom he has played and shared all his childhoodin the hamlet. He has to respect the rule of uxorilocality, a principle upon which the society controls this separation between känakan reaching the age of 12 to 13 for girls and 14 to 16 for boys, the time for these young adolescents to get married. In an area of endogamy, usually between two close valleys, Mäkägwaq and Tämlang for instance, there is no courtship as marriage is prescribed by the parents. Hence divorce is frequent and codified by pala’wan law saraq.

94As sung in the opening of the epic Broken Branches, Käswakan, following raids conducted by the Ilanän enslaving the coastal people of Palawan as well as all the islands of the archipelago in the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, the hero discovers a baby girl still alive in a devastated hamlet. She is a fragile orphan. Full of compassion ingasiq, he decides to take good care of her, for many years mängipat before she will become his wife (Revel 2017b: 15.7).

95A pregnant woman can accept to give up her baby girl in marriage to a man who has affection for her as a mother. In this case of betrothal, the man is to take care of the little one up to puberty; then she will become his wife. The custom of taking a second wife duwäy can favor this second option.

96As for the young maidens and bachelors, they do have to obey the choices of their parents and relatives, a custom that may result in painful conflict. This was the case of Mäsinu who had to bend to the will of his kindred and marry Lamut quite young, instead of going to school inBrooke’s Point Bunbun as he wished.

Facing adversity, sickness, pain and death

97In the hamlet rurungan, small open houses made of bamboo, favor the proximity of parents and their children’s life. In this surroundings, sickness and death are daily events witnessed by the children and these experiences mold their sensitivity. They are capable of silently enduring a sudden outbreak of malaria without complaining. However there are many epidemics läwlabäw. Here N. Revel evokes the memory of the sickness of Pritinyu, the young orphan, brother of Manda, one of the strongest, cheerful and most charming känakan in “Ants Hill” Bungsud, where she shared their life during one year (1971-1972) and was confronted with many diseases.

98Excerpts from February 1972, Nicole Revel’s diary:

99Friday February 4-5… Little Pritinyu has chickenpox and malaria, I think. Doctor Elegado and his wife Becky will arrive tomorrow in the highlands for a brief visit. Wind is blowing… After a hard walk, they reached our place. In the afternoon the doctor was able to check several sick children and adults. He will send me medecines…

100Tuesday 8… Mägrägaq, arrives and announces us the death of Usuy’s daughter, last night. She was 20 and could no longer breathe. On this very morning, she was buried in the wilderness… Luno has measles and keeps on caughing. Lambung takes care of him and says me “You see, this is the flu täringkasu…

101Friday 11… The large meeting house of Lambung is the place where all the sick children are staying. Morning and late afternoon, I take care of them with the pills for malaria and penicillin sirop received from the lowlands. As all the children are sick, life in the kälang bänwa is quite sad…

102Tuesday 15… This morning Mäsinu has a cold sälät, and malaria. We cannot work. I am not feeling well either and I decide to go to Kangrian. I entrusted Mäsinu with all the pills and syrup for the children explaining him how to give them the medecines…

103Sunday 27… I returned to Bungsud and felt very weak on the trail. It took me 4 hours. ‘It is sabläw’, they said and on the spot they introduced me to the Ancestors, explaining them my presence in the Highlands. As I arrived, I went to see my little friend Pritinyu. He was dying. In the afternoon, I brought him a tiny piece of balud, he was so fond of pigeon, he tried, but was unable to eat since several days… At night, suddenly, he gave a howl, some sort of a jump of life. At five in the morning, it was the end. I went immediatly to Manda’s home. His body was still hot and left in the same position. His thin blanket kumut became his shroud. Manda had not given him any medecine since I left. All the adults joined, including the children. ‘Poor one’ sayang ät täw they said. Manda, his elder sister, did not want to live anymore mandiq ku mägbyag. Dangkug, her husband, had to control her. I think Pritinyu could have been saved, had I stayed in the hamlet or had I brought him to hospital. I have deep sorrow… (Nicole Revel’s diary, 1972)

Learning from the forest, learning from the school

104Time has passed… the känakan of the 1970’s are now living close to their children and grandchildren but many have passed away. At the beginning of the 20th century, with the coming of the Thomasites teachers and after World War II with the reconquered Independance, catholic and protestant schools as well as public schools have multiplied all over the provinces of the country. Filipino people highly praise education.

105Along the foothills, South of Brooke’s Point, as a young adolescent, Jose Rilla was able to go to school in Brooke’s Point. After he became Barrio Captain and was close to Mayor Ordinario in 1968, a school was built by the Pala’wan in Tadud.

106The father of Norlita Colili gave one hectar of land in Mangkungän to build an elementary school and gave to all his children the opportunity to be educated and able to integrate the main stream of the Filipino society, without forgetting the Pala’wan values and tradition Adat (cf. Plate 6 below).

107Norlita Colili’s comments on a recent development (cf. Plate 7 below):

108For several decades, the Department of Education has sent school teachers from other provinces to teach the native children in Tagalog and English. However, in 2015, the Philippine Government decided to modify the elementary schooling system emphasizing a multilingual education nationwide8. In the Highlands of Brooke’s Point and the vicinity of Amas, within the frame of the ‘Indigenous Peoples Education Program’, a Pala’wan school opened in two hamlets, Päwpanäw and Käluy, while in Tabud an attempt is undertaken too. A key concept of this program is that the teachers should adapt their lessons plan to the local sociocultural context and a school started modestly two years ago in Pala’wan language. Here is an example of how the counting is being taught in the Pala’wan school: As children went to collect wood for fire with their teacher, each one would count the number of pieces collected and a calculus lesson would follow.

109Flash sonic sentences in Pala’wan are used to teach orthography: in order to introduce the letters Y, A and D for instance, they would say: Aya daya. Yaya daya, meaning ‘Wow, the Highlands. The Highlands only!’

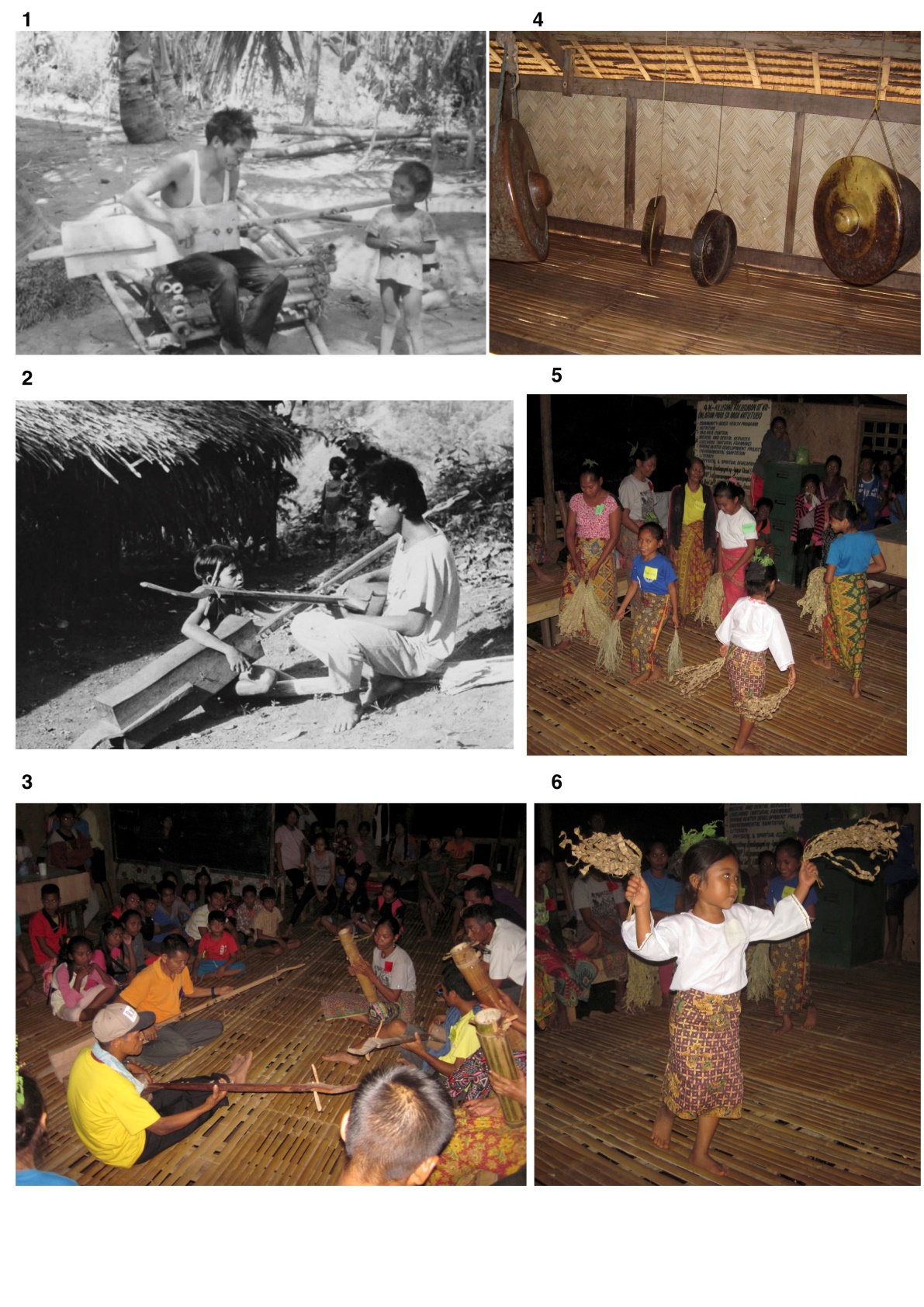

110In addition to learn how to count, read and write, the Pala’wan schooling wishes to transmit the local knowledge and know-how to the young generation, in order to root them in their culture via the school too. For this purpose music training is being convened. Children gather with adults in the large meeting house and girls learn how to dance mägtaräk and make ornaments silad, of folded kugun leaves, or other grasses, while boys are shown how to play the gongs ensemble basal– a drum gimbal, small rim gongs agung and sanang. Traditionally, gong music accompanies all festivities and celebrations.

111Later in the night, children learn how to play a quieter music with the long lute kusyapiq, the bamboo zither pagang, exclusively played by women, the mouth harp äruring or äruding and two distinct flutes bäbäräk and suling. In the school context, children are taught music by the elder explicitely and out of ritual or daily life context, while traditionally, they would silently observe and little by little they would play, as transmission is quite effective too by way of imitation and a non-verbal transmission. This is a great difference… (Norlita Colili, Mangkungnän, 2016)

Plate 6: känakan at school in the Highlands,

© Norlita Colili, 2015-2016

Modest shelter and the various ages attending school in the mother tongue, Päwpanäw, 2015-2016.

Plate 7: känakan and music,

© Nicole Revel, Anna Fer, and Norlita Colili

1. Rudis listen to “Dog” Iräng, as his father plays bird music bägit on the lute, 1971.

2. A känakan wishes to learn how to play kulilal music on the lute kusyapiq; Turkit, a bachelor subur facing him in a reverse position, shows him, 1988.

3. Känakan and schooling: they are shown how to play kulilal music, (2 lutes, 3 bamboo zithers pagang). Here they are separated from the performers and have to be attentive.

4. 1 drum gimbal, 2 agung, 2 sanang make a complete set to play gong music basal, 1988.

5. känakan girls are learning a percussion dance on the bamboo floor taräk in measure, with 12 different rhythms of the gongs ensemble, out of 14, Amas, 2016.

6. A young girl in full attire, handling ornaments of folded leaves silad, is performing the taräk, Amas, 2016.

Conclusion

112Pala’wan children are cheerful, free, resistant and peaceful. By playing and living together as siblings, känakan do practice fellowship and the related values organizing this society at an early age.

113Here hierarchy, strong leadership, and violence are absent but equality, sharing, compassion, modesty and an irresistible sense of humor are praised as values and personnal qualities (Internet website “Anthropology and Anarchy (C.J.H. Macdonald’s Site)”).

114The impact of the plant world, as well as that of the animal world, their subtle resonance, mold the children in their individual and collective being, their imagination, their sensibilities and in the way they apprehend life in order to survive.

115This technologically simple and frugal society in monsoon Southeast Asia, has generated a holistic symbolic worldview and a social organization that is loose, non-authoritarian, but highly operative, reflecting somehow the harmony and lavishness of the forest9. The respect for the linguistic diversity parallels the respect for biodiversity. Together they are a form of resistance to globalization.

116Monolingual elementary schooling in the Highlands started in 2015, with a lot of hope, as the känakan are eager to attend school. Hovewer, shortly after, it was disrupted by the coming in of members of the New People Army (NPA). When Martial Law was proclaimed in the Philippines on September 19th 1972, there was no guerilla warfare in Palawan. Only recently, since May 2015 up to now, groups of armed people are roaming around forest and hamlets on the eastern and the western slopes of Mont Mantalingayan Käbätangan. They disturb the daily life of the Highlanders and their children, trying to recrute, generating trouble among the members of the communities, provoking conflicts with the Military. In spite of these threatening presences, a school opened in 2016in Kälui, more than a hundred children are now being taught by three licensed teachers.In Päwpanaw, the school started earlier, in 2015, but was interrupted by troubles in June and resumed in April 2017. Around thirty children and a dedicated Pala’wan para-teacher are now attending this school. The Department of Education Indigenous Peoples Education (DepEd IPEd) provides teachers and materials. Parts of the scientific works published after a long lasting collaboration with their parents and grandparents are being used.

117It is too early in the present situation to appreciate the value of this education. Let us express the hope that schooling in the mother tongue will continue and will contribute to safeguard the Teaching of the Ancestors (Revel 2001, 2008a, 2011) and their know-how, instead of dispising it, neglecting it or erasing it. May the Commemoration oftheMaster of Rice Tamwäy ät Ämpuq ät Paräy and the Commemoration of the Master of Flowers Tamwäy ät Ämpuq ät Burak, relating nature to their knowledge and artistic symbolic ritual expressions, not be abandoned (cf. Plate 8 below). May all the practices and memories related to staple food cultivation (rice, corn and tubers in association) and to foraging forest products not be forbidden by external laws, nor forgotten by the young generations, so that the way of life in the Highlands, together with the elementary schooling in the mother tongue, would contribute to interiorize an ancient knowledge to modernity and would facilitate the integration of the teenagers in today’s global world (Revel 2013).

Plate 8: känakan playing gongs with machetes and cooking pot covers Basal ät takäp ät kandiru on the way to felling trees to open a new upland field,

© Anna Fer (1988)

Acknowledgements

We want to express all our gratitude to the känakan, their parents and grandparents, who, since 1970, have sharedtheir life and knowledge with us with enthousiasm. Their consent is very clear since the very beginning of our collaboration and copies of the pictures have been shared with them as well as books and many other forms of publications (texts, articles, CD, CDRoms, DVDRoms, websites). H. Xhauflair would like to thank warmly the local political authorities and the National Museum of the Philippines for supporting her research, especially Timothy Vitales for his assistance in the field and John Rey Callado and Danilo Tandang for identifying the plant taxa involved. She has been funded by the MNHH and IRD to conduct fieldwork and by the Fyssen Foundation during the writing of this article. She is also indebted to Valéry Zeitoun, Victor Paz, Eusébio Dizon, François and Anne-Marie Sémah, Claire Gaillard, Hubert Forestier and Alfred Pawlik who helped her to conduct this work.

Bibliographie

Berque A. 2017 « Existe-t-il un mode de pensée forestier », Conférence EHESS Forêt, arts et culture : l’esprit des lieux, 28 janvier 2017.

Cuvelier F. 2008 Taut Batu. Via Découvertes Production, Film, Format 16/9 Letter Box, Length 16’19”.

Colili N. & Andaya N. 2008 The Tingkäp and other crafts of the Pala’wan. NTFP-TF for South and Southeast Asia in behalf of the Pala’wan Community & NATRIPAL.

Internet website Anthropology and Anarchy (C.J.H Macdonald’s Site)[https ://sites.google.com/site/charlesjhmacdonaldssite/Home]

Macdonald C.J.H. 1977 Une société simple. Parenté et résidence chez les Palawan (Philippines). Paris : Institut d’Ethnologie, Musée de l’Homme.

Macdonald C.J.H. 2007 Uncultural behavior. An anthropological investigation of suicide in Southern Philippines.Honolulu : University of Hawai’i Press.

Merleau-Ponty M. 1945 Phénoménologie de la Perception. Paris : NRF Gallimard.

Revel N. 1980 « La rhétorique des spécialistes du droit coutumier palawan » (65-78), in A. Cartier (ed.) Langues formelles, langues quotidiennes. Paris : Publication de Paris III-Sorbonne.

Revel N. 1990-92 Fleurs de paroles, histoire naturelle Palawan. Volume 1 : Les dons de Nägsalad.Volume 2 : La maîtrise du savoir et l’art d’une relation. Volume 3 : Chants d'amour / chants d'oiseaux.Paris : Peeters–SELAF.

Revel N. 1998 « As if in a dream… Epics and shamanism among hunters, Palawan island » (7-30), in N. Revel (ed.) Épopées. Littératures de la voix, Diogène 181.

Revel N. 2001 « The Teaching of the Ancestors », Philippines Studies 49(3) : 417- 428.

Revel N. 2005a « L’art de communiquer : Relations hommes-oiseaux à Palawan » (479-492), in É. Motte-Florac & G. Guarisma (eds.) Du terrain au cognitif. Hommage à J.M.C. Thomas. Paris : Peeters-SELAF.

Revel N. 2005b « The symbolism of animal’s names: Analogy, metaphor, totemism » (339-444), in A. Minelli, G. Ortalli & G. Sanga (eds.) Animal names. Venezia : Istituto Veneto di Sciencze Lettere ed Arti.

Revel N. 2008a « Évitement, respect, pudeur, recours et transgressions, Palawan, Philippines » (121-141),inM. Thérrien (ed.) Paroles interdites. Paris : Karthala-Langues O.

Revel N. 2008b « L’air et l’eau dans la pensée cosmogonique palawan » (77-97), in G. Calame- Griaule & B. Biebuyck (eds.) La ronde des éléments. Paris : Inalco, Les Cahiers de Littérature Orale, CLO 61.

Revel N. 2009 « Palawan Soundscape » (78-90), inM. Mangahas (ed.) Social science diliman. Quezon City : University of the Philippines.

Revel N. 2011 « The gifts of the weaver, their becoming at the turn of the 21st century » (49-67), in Kalikhasan in flux : Indigenous people’s creativity in a changing natural environment. Proceedings of 32nd UGAT Conference, National Museum Manila, Oct. 20-23, 2010. Quezon City : AGHAMTAO.

Revel N. 2013 « Vivid and virtual memory » (27-58), in N. Revel (ed.) Songs of memory in Islands of Southeast Asia. Newcastle upon Tyne : Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Revel N. 2017aLes arts de la parole des Montagnards Pala’wan. Une mémoire vivante en Asie du Sud-Est / Palawan Highlanders’ verbal arts. A living memory in South-East Asia. Paris : Éditions Geuthner.

Revel N. 2017b « Box 15 Palawan », in Internet website Philippines Epics and Ballads Archive[http://epics.ateneo.edu/epics]

Revel-Macdonald N. 1979 Le Palawan. Phonologie. Catégories. Morphologie. Paris: SELAF.

Revel N. & Macdonald C.H.J. 2016Fonds Nicole Revel & Charles Macdonald au CREM

[http:// archives.crem-cnrs.fr/archives/fonds/CNRSMH_Revel]

Vallombreuse P. 2017 The valley, Palawan Philippines 1988-2017. A photography exhibit at the National Museum of the Philippines.Manila : Alliance française, National Museum, NCCA, Embassy of France.

Vallombreuse P. & Macdonald C.J.H. 1993 Taw batu, Hommes des rochers. Paris : Musée Albert Khan.

Xhauflair H., Revel N., Vitales T.J., Callado J.R., Tandang D., Gaillard C., Forestier H., Dizon E. & Pawlik A. 2017 « What plants might potentially have been used in the forests of prehistoric Southeast Asia? An insight from the resources used nowadays by local communities in the forested highlands of Palawan Island », Quaternary International 448 : 169-189.

Notes

1 känakan: the root word anak “child” kä- + anak + -an affixe of plural: “the children”; in fact here, a group of siblings including the first cousins between 3 and 12 years old, an age group. The affixe also connotes the abstract “childhood” (Revel-Macdonald 1979).

2 Bird’ touch Läpläp bägit is an anhemitonic pentatonic scale (Revel 1990-92, 2009, 2017; Revel & Macdonald 2016).

3 José Rilla and Mäsinu Intaräy told N. Revel their respective life story in the sharing presence of Mägrägaq, a highlander, son-in-law of Usuy, during three evenings (August 20-21-22, 1995) as they were working together at her bahay kubo, a home made of vegetal materials, on Tataran Island, (South China Sea, now Philippine West Sea), facing Lipuun Point, Tabon Caves, and the near by little town of Quezon. These were delightful moments of sharing in friendship and trust. N. Revel taped what is the first emplotments of their respective life in August 1995, then, later on, transcribed and translated them in collaboration with Jose Rilla.

4 In the 1980-1990’s, around 37 families scattered in 12 hamlets used to take shelter in the Singnapan valley (Revel 2008b; Vallombreuse & Macdonald 1993: 19).

5 Isnig was filmed for an ARTE documentary Taut Batu by F. Cuvelier (2008). N. Revel translated the interviews with the Pala’wan.

6 See Igum “Riddles”, Ch. VIII, pp. 209-223, (DVDRom 11’36”).

7 See Bisara, Jural discussion, Ch. VII: 177-187 (DVDRom86’43”).

8 After a positive experiment with Kalinga children and other autochtonous children in the world, the Primary Education Program of Unesco encouraged the use of mother tongues.

9 Underlying this conclusion is the notion of “chaînes trajectives” explained by Berque (2017), but this is a complex matter that would need another paper.