- Accueil

- N° 8 (2018) / Issue 8 (2018)

- Playing at etiquette, learning respect in contemporary Middle Gobi (Mongolia)

Visualisation(s): 5416 (190 ULiège)

Téléchargement(s): 115 (0 ULiège)

Playing at etiquette, learning respect in contemporary Middle Gobi (Mongolia)

Document(s) associé(s)

Version PDF originaleRésumé

Jouer à l’étiquette, apprendre le respect dans le Gobi Moyen contemporain (Mongolie).L’étiquette mongole (yos), héritée du mode de vie pastorale, est une « technologie morale » omniprésente qui ordonne les relations selon les valeurs de respect et de calme. À la fin des années 2000, les enfants du Gobi Moyen grandissent dans un contexte de changements économiques et sociaux qui remettent en question les régimes de valeur traditionnels. Ce texte examine dans quelle mesure, et comment, les enfants s’approprient l’étiquette en soulignant la façon particulière dont la yourte, en tant qu’« espace moral ordonné », joue un rôle important dans l’apprentissage de celle-ci. L’article vise à montrer que l’étiquette est renouvelée, mais qu’elle se reproduit, à chaque nouvelle génération, tout en restant le vecteur de valeurs intergénérationnelles partagées, notamment celles du respect et du calme.

Abstract

The Mongolian etiquette (yos) inherited from the pastoral way of life is an ubiquitous “moral technology” that orders relationships according to values of respect and calmness. In the late 2000, children raised in the Middle Gobi grew up in a context of socio-economic changes that put into questions traditional regimes of value. This paper examines whether and how children make etiquette their own in the contemporary context. I demonstrate that the process of learning etiquette makes yos a practice whose meaning is produced anew by each generation in a changing historical context, while also the medium of cross-generational shared values of calmness and respect. I also show that the yurt as a “morally ordered space” plays an important part in playfully learning yos.

Abstracto

Jugando a la etiqueta, aprender el respeto en el Gobi Medio contemporáneo (Mongolia).La etiqueta mongol (yos) heredada del modo de vida pastoral, es una “tecnología moral” omnipresente que ordena las relaciones según los valores de respeto y de calma. A finales de los años 2000, los niños del Gobi Medio crecen en un contexto de cambios económicos y sociales que ponen en duda los regímenes de valor tradicionales. Este texto examina en qué medida, y cómo los niños se apropian la etiqueta, subrayando el modo particular en el que la yurta, como “espacio moral ordenado”, juega un papel importante en el aprendizaje de ésta. El artículo pretende mostrar que la etiqueta está renovada, pero que se reproduce en cada nueva generación, quedando el vector de valores intergeneracionales compartidos, particularmente los del respeto y de la calma.

Table des matières

Introduction

1In the late 2000, nearly twenty years after the fall of the Communist regime, Mongolian children raised in the Middle Gobi grew up in a context of socio-economic changes, constitutive of the post-Socialist era of the market. Nearby mining activities, popular foreign TV-series, access to mobile phones and progressively to internet converged in presenting old and young generations with forms of public presentations and sociality at odd with Mongolian traditional hierarchical mode of relating.

2Korean TV series were broadcasted daily and old and young people gathered on evenings to watch popular series. Whether the series was a crime drama or a comedy, virtually all episodes included some highly dramatic interactions between the characters. These interactions often triggered amused comments from those watching. For instance, they made fun of how Korean people cried frenetically when a person died. In the same way, the children of my host family – Bilgüün, Otgono, and Batuhan – found it funny when I once burst into tears. Bilgüün, who was an especially good performer, loved making her cousins and friends laugh by mimicking my weeping, her face in her hands, for weeks after it had happened.

3In rural Mongolia, interactions, in daily and ritualized contexts, are orchestrated according to “yos”, usually translated as “rules” (Humphrey 1997:25), but that I chose to translate as “etiquette” – a term usually reserved to elite customary code of politeness –, to emphasize that “yos” is a formal code which produces “distinction” (Bourdieu (2016[1979]). Mongolian etiquette favours self-control, commands calmness and orders relations according to a hierarchical economy of respect. Old people occupy the highest status in the hierarchyof social seniority.Elderly people (ahmad) are expected to be the most yostoi – literally “with etiquette” (Højer 2003: 109). Getting older is seen as a process of progressive acquisition of wisdom, self-control, and peacefulness (Humphrey 1996: 29). The respect due to older people is an objectification of the association between old age and the acquisition of these moral qualities. As such, junior people’s duty to show respect (hündlel) to older people acknowledges their comparative lack of accumulated experiences and self-control.

4Living with Otgono and Batuhan, two Mongolian boys growing up in the Middle Gobi, first when they were, respectively, three years old and one year old, and then between the ages of five and six years, and three and four years, I witnessed how they progressively learned to enact etiquette through verbal instructions, self-initiated imitation, and positive and negative reinforcement. Through these daily interactions and observations, they came to perceive their home, including the objects and bodies within it, as intrinsically ordered and inherently imbued with moral qualities of respect, or lack thereof.

5Initially, their parents, Tuyaa and Erdene, had no expectation that Otgono or Batuhan would follow etiquette. However, as they grew older, adults considered that they were able to control and understand their actions, and no longer indulged that they behaved as unruly little ones disrespecting hierarchical code of relationship (Michelet 2015). Still, children’s loud and free behavior continued to be tolerated outside, but their parents expected them to adopt a discreet and respectful attitude at home, especially in the presence of visitors. In the regional literature, many anthropologists have shown interest in children; however, children were and largely remain a “small subject” (Lallemand 2002). In a seminal 1974 article, French anthropologist Françoise Aubin pioneered work on Mongolian children by offering a historical and institutional perspective on the status of children within Mongolian society. More recent works by French anthropologists have been interested in, respectively, birth and postpartum rituals (Bianquis 2004; Ruhlmann 2010), and in socialization as revealed by riddles and proverbs (Aubin 1997). In her monograph on Mongolian body techniques, Lacaze (2010) describes pregnancy, birth, caregiving, and socializing practices. Lastly, Ferret (2010) draws a comparison between the types of actions used in educating children and taming horses. All these studies have in common a focus on adults’ perspectives and how children are acted upon.

6By contrast, work by British anthropologist Empson (2003, 2011) among the Buryats of northern Mongolia is inscribed within the “new paradigm” of childhood studies, as she examines both ritualized and everyday practices and presents the perspective of both children and adults. Moreover, she does not consider children in and of themselves, but rather for the perspectives they offer within a study of Mongolian relatedness and personhood (2011). While Empson underlines the importance of developing domestic and herding skills in becoming family members, she does not explore the actual processes through which children take positions within their families or learn to develop these gendered skills. Exploring the learning processes through which children become competent at etiquette, to understand how etiquette is re-produced in the contemporary context is the aim of this article.

7In this paper, drawing on an “ethnography of the particular” (Abu-Lhugod 2016, 2008), I examine the processes through which Otgono and Batuhan progressively made etiquette their own. We will see that the yurt as a morally ordered space played an important part in this process. Following the assumption developed in studies of material culture that objects and actions are not “symbols” or “materialization,” but producer and catalyzer of meaning in themselves (e.g., Gell 1999; Henare, Holbraad & Wastell 2007; Lemonnier 2012; Myers 1988), I examine how space and objects were involved in making children aware that their very body and actions participate to an economy of respect.

Fieldsite and methods

8Early in 2008, I arrived in the administrative center of one of the fifteen districts of the Middle Gobi region where I conducted a family-centered ethnography, collecting data by embedding myself in the network of my host family over twenty months. I do not disclose the name of the district where I conducted fieldwork and changed the names of the persons described to keep the identity of my informants anonymous.

9I lived with a couple, Erdene and Tuyaa in their late twenties, their sons Otgono (born in August 2002), Batuhan (born in February 2005), one of their nieces Bilgüün (born in January 2000) and later their newborn baby daughter (born in April 2009). I observed and participated in the daily activities of these four children, who became the primary focus of my study, moving with them between the center of the district (töv) and the countryside (hödöö)1. My choice of adopting a family-centered focus represents a deliberate research strategy especially adapted to the Mongolian context. Networks of relations are generally developed from membership in a given (nuclear) family (ger bül) and extended family group (ah düü). Participant observation seemed particularly appropriate in a context where adults expect novices to learn through observing and participating and tend to discourage questions (Michelet 2016a).

10My approach is based on the acknowledgement that most of our knowledge is implicit and thus learned and accessible through practice (see Bloch 2012:143-85; Malinowski 1932:1-25; Warnier 2007). As a result, the only possible method to understand other people and share their implicit knowledge is to build this implicit knowledge oneself through participating with others in their activities. This stance also means that verbal knowledge has to be treated as a special kind of knowledge. A person’s a posteriori reflexive rationalizations produced in conversations and interviews cannot be assumed to have motivational or explanatory power over their actions. Although I complemented my observations with semi-directed conversations, I favor the description of practices as my primary data source. I should emphasize that children’s lives in rural Mongolia are not segregated by age and thus making them the focus of my research implied developing relationships with a much broader network of people: their family members, relatives, teachers, friends, classmates, etc.

11At the time of my fieldwork, the Mongolian rural economy relied on a mixture of mobile pastoralism, services and confidentially the mining industry in which a few men of the district had just started to take part further south, while their family still lived in the district. In 2008-2009, according to the administrative registry, among the few thousand inhabitants who lived in the district, less than a third were listed as sedentary residents of the administrative center.The majority of the population was thus registered as herders living in the countryside. My host family counted among the sedentary family of the district. Although they had herd, it was cared for by relatives. The head of the family generated extra revenues by various kinds of local trades (from selling silver bowls to TV antennas), while Tuya was a bank employee at a local branch.

12Throughout my fieldwork I remained a “peculiar person.” First, because of my European facial traits and white skin color. Second, because at age twenty-eight I was still childless, which made me a “girl” (ohin) rather than a “woman” (emegtei). Third, because I interacted with children in ways that were not “adult-like.” I intentionally played with my status of “stranger” to establish a position where I could partake in children’s sociality and everyday life as an “auntie without authority” (for a similar approach, see Corsaro 2003: 7–35; and Mandell’s [1998] method of taking the “least-adult” role). In the kindergarten and in school where I gave English lessons, children were told to address me as Od-bagsh (Teacher-Aude), but, imitating Otgono and Batuhan, they most often called me Od-egee (auntie-Aude). At first, children (and adults) were surprised that I did not behave like a “normal teacher” outside of the time when I taught them English. Instead, I took part in their games, asked them questions, observed them and took notes, and did not intervene when their teachers left them unsupervised. As a result, children were comfortable committing small acts of mischief in my presence, which they would not dare commit in the presence of other adults. I also consistently refused to intervene in their disputes. I thus successfully managed to minimize the position of authority that the status of egch and teacher conferred upon me, albeit while showing enough awareness of Mongolian etiquette to make my behaviors appropriate.

Body techniques under control

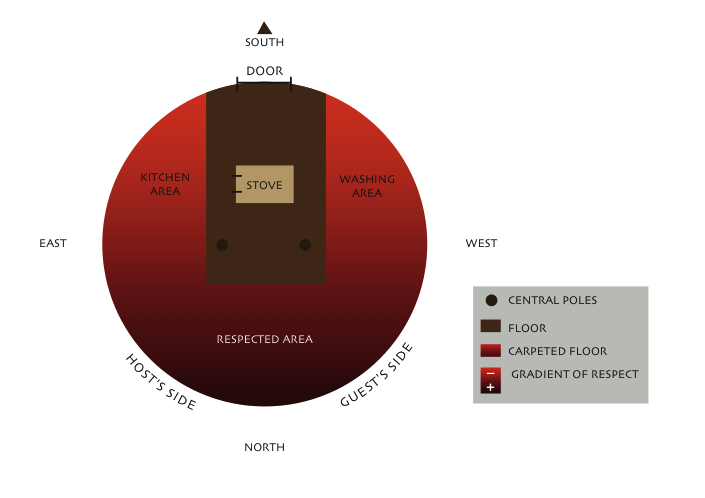

13All yurts (ger) are oriented so that the door opens toward the south. Also, the spatial organization of yurts within it is the object of shared conventions along a double north-south, east-west axis (Humphrey 1974). As a result, upon entering any one yurt, one can confidently predict how furniture will be arranged and where to sit depending on one’s status (see also Beffa & Hamayon 1983; Dulam 2006: 33-44; Empson 2007: 61; Humphrey 1974; Humphrey 2012; Sneath 2000: 216-21). The term ger has a broader meaning of home as a moral entity with which the members of the household identify and are identified. In the countryside and district center where I conducted fieldwork, the large majority of people lived in yurts and those living in flats or houses organized the space reproducing the moral structuration of space within yurts (Marois 2006).

14The northern part of the yurt (hoimor), farther from the door, is considered the cleanest/purest (ariun) and honorofic (hündtei). It is where the domestic altar and family picture frames are located and where older men sit during visits. The eastern area close to the door is used for cooking, and the western area for cleaning or other mundane activities. This general framework is adjusted to daily activities and qualified relationally, as junior people (düü) should not sit higher than their seniors (ah) and everyone should sit so as not to direct their backs or feet toward others. When guests enter, they automatically walk toward the western part and sit there. If members of the host family are in the western part, they move to the eastern part, expect for the head of the family who might stay in the western area, further north than the guests.

15Taking position in the yurt is intrinsically relational. The place where one sits in relation to cardinal points but also in relation to others, the sitting position adopted, the way things are offered and taken, and the words chosen to address others all mark and signify mutual, albeit asymmetrical, respect between juniors and seniors, women and men, hosts and guests. These formal practices are underlined by the same logic that applies to bodies and to domestic space alike: what is higher or north is valued over what is lower or south (see also Beffa & Hamayon 1983; Hamayon 1970, 1971: 144; Novgorodova & Luvsanzav 1971; Humphrey1974a, 1978: 97-8; Jagchid & Hyer 1979: 62-72; Sneath2000: 197, 216-35; Dulam 2006: 31-82; High 2008: 36; Lacaze 2012).

16Otgono and Batuhan seemed to spontaneously pick up on some aspects of etiquette (yos) and were encouraged to do so by the positive attention they received when they took the initiative of imitating men’s body postures and sitting positions. Batuhan, for instance, loved sitting with his legs crossed like a man. Adults never failed to notice it and to comment with amused compliments. Adults (their parents, grandparents, or close relatives) occasionally brought Otgono’s and Batuhan’s attention to the fact that they were transgressing etiquette. For instance, around the age of three years, Batuhan and Otgono were sometimes stopped when they tried to pass over other people’s legs and asked to instead pass behind their back.

Figure 1: The southern part of a yurt in the village center

Figure 2: Schema of the qualification of the space within yurts (with south direction at the top following Mongolian conventions)

Source: Illustration by C. Calais

17The two boys were also made aware of specific elements or areas within the yurt that command respect. For instance, once, as Batuhan (4 year-old) was going out of his grandfather’s yurt, he tripped over the door threshold, an action that is considered inauspicious. His grandfather asked him to come back in and place a piece of dung in the hearth. No explanation was given to him as to why it is wrong to step on the doorstep and why making an offering to the hearth would repair this unvoluntary misdeed. As underlined by Lemonnier (2012), “material actions” and objects are in themselves means of communication and nonverbal signifiers, so that children receive information from them even when the meaning or purpose of such actions are not elicited verbally. The young boys were given no reason as to why etiquette should be respected. However, the actions adults required of them “to repair” (zasah) their misdeed drew their attention toward the fact that certain parts of the house, such as the door threshold, the central pillars, or the stove had special material attributes which required that people behave towards them with respect, an information that was corroborated and fleshed out in ceremonial instances, as I will develop later in this section.

18In other instances, Batuhan was asked not to direct his feet toward the altar, and not to grip or lean on one the two central poles, which support the roof structure. His misbehaviors were pointed out, but he was not reprimanded. He sometimes took advantage of his prerogatives as younger child and misbehaved intentionally to see whether it attracted the attention of his parents. By the time he had developed proficient linguistic skills and was thus considered capable of understanding the meaning of his actions, he got harshly scolded when he broke etiquette. In instances of serious disrespect, such as a time when his mother caught him playing with sacred objects on the altar, Batuhan received physical punishment. This is one of the only instances where I saw a child of my household punished physically.

19Through these everyday observations and corrections, the repetition of material actions, and the convergence of different practices, Batuhan was made to construe the space within the yurt and some of the objects and bodies within it as inherently moral. In a similar fashion as Bourdieu’s (1972 2000]: 61-82) analysis of the moral ordering of Kabyle houses, daily life at home was a perpetual reinforcement of the right way to perform activities in the right place. Cooking, for instance, was always performed in the southeastern part of the yurt; laundry and toilet were performed in the southwestern part; when going to bed we all laid down with our feet oriented toward the door; etc. Otgono and Batuhan thus progressively learned to orient themselves and behave according to the material and symbolic qualification of space within the yurt and in relation to other people present.

20Otgono (6 years old), who was Batuhan’s elder, was not only expected not to misbehave but also to “pro-actively” use proper “body techniques” (Mauss 1936; see Lacaze 2012 for the documentation of Mongolian “body techniques”). In the presence of visitors or when visiting other people, his mother sometimes told him to “sit in a nice way” “goyo suu”, by using the term “goyo” which means “beautiful”, instead of “zöv” most commonly used to designate “correct” behaviours, she put the emphasis on the aesthetic quality of body manners. In other occasions, such as when he got caught by supporting himself with hands while sitting or standing up, Otgono was mocked or reprimanded for not “holding his body” properly (biyee’n barih).

21The older they grew, the more imperative the expectations that Otgono and Batuhan behave appropriately became. Although the atmosphere remained quite relaxed among us, Otgono and Batuhan grew attuned to seeing certain ways of positioning or using one’s body as inappropriate so that they no longer needed to be told how to behave but themselves knew to exert body control and to sit appropriately rather than comfortably, especially in the presence of visitors. When they failed to behave according to adults’ increasing expectations, they could be humiliated for bringing shame to their parents to the point of making them burst into tears, a behavior they had been taught to forego.

22I have thus far highlighted everyday instances when the two boys learned the moral quality of space and bodies within their home by their direct involvement in coordinated actions with others or by being explicitly shown the right way of doing things. This lesson was also produced and reinforced in ceremonial contexts. All domestic ceremonies – first haircut, taking in a daughter-in-law, weddings, funerals, lunar New Year, etc. – take place and involve hosting visitors following the same ritualized sequence of food sharing (Ruhlmann 2015). On such occasions, sitting positions and sitting order were more formally observed. In all of these ceremonies, the domestic altar was given a specific salience as visitors who exceptionally had to leave the home through the eastern part, stopped by the altar and rolled the prayer mill before going out. In certain homes, the domestic altar was all the more respected, that it contained a Buddhist deity (burhan), in the form of an object or picture. Guests who visited this home kneeled and place their forehead on the altar before leaving. The stove, which occupies the central place in the yurt and hosts the domestic hearth, constituted another locus of ritualized actions. In addition to the interdiction against burning rubbish in the stove, the hearth was given the upper, most honorary, part of delicacies (deesh) on important ceremonies. Certain families, including Erdene’s, also performed a yearly collective ritual dedicated to worshipping the hearth.

23Children witnessed and imitated everyday ritualized actions and took part in ceremonies. These “material actions,” mundane and ritualized, weave people and objects within homes by operating with “redundancy” (Lemonnier 2012) and materialize the space morally by commanding respect towards certain objects but not others. The way no explanations were given to children as to why it is wrong to step on the doorstep, to throw rubbish into the hearth, to orientate one’s feet toward the altar, etc., but also as to why a collective ceremony is organized to worship the domestic hearth, why only men and elderly women exchange snuff tobacco bottles, why women offer the first scoop of milk tea to the sky (tenger)—reinforced the intrinsic quality of nonverbal signifiers of material actions, and domestic objects involved in ritualized actions. Csibra & Gergely (2011) highlight the striking character of ritualized actions, whose functional “opacity” renders them enigmatic and thus prone to awake children’s curiosity. The way children paid attention to ritualized actions and made their own the hierarchical ordering of space and bodies was confirmed during pretend-play during which Bilguun, Otgono and Batuhan loved reenacting them, a point I will substantiate later.

The contextual enactment of etiquette, a learning challenge

24Enacting etiquette supports the development of personal bodily control, as well as requires the constant awareness of other people. Beyond the technical and emotional difficulties of learning to control one’s physical movements, an important challenge encountered in learning etiquette is that the degree of formality at which it is observed depends on context. Adults considered that some of the rules of good conduct were unconditional and had to be observed at all times, such as performing devalued activities and storing devaluated things in the southern part, facing others when sitting, sitting for eating, sitting in a way to face the hearth and others, using the right hand to give things, serving elders first, etc. But they observed other rules contextually depending on the presence of others. For instance, etiquette requires one to sit without leaning on one’s hand, to not extend one’s legs, and to not orient one’s feet toward the hearth. However, at home, among ourselves or in the presence of familiar neighbors, sitting positions could be extremely relaxed. When chatting in the evenings, we sat leaning on our arms or layed comfortably. When watching TV, which was initially placed in the northern central part of the yurt, orienting our feet northward (but not toward the altar, located to the northeast in this yurt) was tolerated.

25At times when unfamiliar visitors came in, if Bilgüün, Batuhan, and Otgono were playing in the northern or western side of the yurt, they generally spontaneously moved from the western part, where visitors sit, and relocated themselves to the eastern part. They were also sensitive to the more formal attitude adopted by adults and knew to keep quiet unless they were directly addressed. Erdene’s father explained to me that when he was a child, he was never allowed to sit, let alone play in the northern part of the yurt. Moreover, when visitors came to the home, his mother always sent him and his siblings outside. At the time of my fieldwork, it seems that children grew up experiencing a much more flexible use of space within yurts than their elders did. I suggest that this more relaxed attitude can be partly explained in relation to a contemporary activity, namely watching TV. Let me further explain this point to highlight the way people contextually and flexibly enact etiquette.

26In the countryside, an increasing number of households – those with solar panels and batteries – were equipped with a TV set. In the village, households were linked to the electrical grid, and almost all households had a refrigerator and a TV set2. New appliances and modern furniture were integrated within yurt interiors in accordance with the symbolic qualification of space, and as such proved the generative capacity of etiquette to frame people’s relations to new items and practices. In the Middle Gobi, washing machines were always placed in the southwestern part, next to where the soap, toothbrushes, and towels were to be found. Unless electrical installations prevented it, fridges were placed in the southeastern part with all cooking utensils. Modern sofas replaced Mongolian beds along the eastern and western walls without changing the family’s sitting and sleeping arrangements. TV sets were the only object whose location varied.

Figure 3: Child daily playing in the northern area, north of his great-grand-mother

Figure 4: Guest drinking tea in a relaxed sitting position

27I suggest that this is due to the fact that being a focus of attention, TV sets disrupted the distribution of people in the yurt, infringing on both the absolute qualification of space and relational qualification of body positions.

28Not all activities performed within yurts involve interactions; however, all of them are performed orienting one’s body toward the hearth at the center of the yurt (while never directing the soles of one’s feet toward others, but toward the door) so that it is always possible for people to see each other. Only in Erdene’s home did I see a TV set placed in the central uppermost northern part of the yurt. This incontestably conspicuous statement made by Erdene was also, somewhat paradoxically, the arrangement that allowed us to watch TV without disrupting rules of sitting and acting in the yurt. The fact that it was central and north allowed hosts and guests, men and women to watch it without having to move from the place etiquette prescribed. In other homes I visited, TV sets were located either northwest or northeast, occasionally southwest. In these settings, when watching TV, the goal of seeing the screen and seeking a comfortable position took precedence over respecting etiquette. The quality of sound and picture was often quite poor, so people had to cluster close to it in a limited space, and thus inevitably turned their back to people sitting on the other side.

29The contextual enactment of etiquette implies that learning etiquette is not as simple as learning a list of rules about how to behave, but also requires an understanding of contexts and expectations of others as well as the capacity to generate appropriate behaviors in novel situations. In Outline of a theory of practice (2000 [1972]: 221-416), Bourdieu proposes to explain how people are able to act in conformity with “rules” without actually obeying the “rules” of which they would have an explicit knowledge. He argues that cultural practices are themselves the product of a limited number of principles that are embedded in and can be learned through practices. Through practice, these underlying structuring principles become embodied in the form of “habitus,” a system of structured dispositions that is then mobilized to generate behavior in new situations (2000 [1972]: 286). Following Bourdieu’s suggestion, I now turn to investigate how children use and learn etiquette as a generative code of conduct.

Children’s generative approach to etiquette

30Once Bilgüün, Otgono, and Batuhan had become competent at enacting etiquette, they respected it selectively depending on whom they interacted with and in whose presence. Otgono, for instance, made sure to never step over his father’s legs but liked to test whether it was important to me. At home, catching one of us (other children and myself) not respecting etiquette, for instance when the two young boys caught me supporting my head with one of my hands, was often a valuable opportunity to gain authority. The fact that I was senior to them made correcting me incongruently fun for them. At times they even probed “new rules” on me, demonstrating their generative capacity to formalize situations. Let me illustrate this point by describing an interaction with Otgono.

31In spring 2009, Erdene and Batuhan had gone to the countryside to help comb cashmere from goats and Tuyaa was in the regional capital waiting to give birth. For nearly a month, I was left in charge of Bilgüün and Otgono at home. During this period, I generally served food to Otgono first and sometimes referred to him, most often jokingly, as the head of the family (geriin ezen). Etiquette commands that the head of the family be served first—Erdene being absent, Otgono (6yo) was de facto replacing his father in this position. Four months later, as we were about to enter the yurt after coming back from a visit to Otgono’s great-grandmother, Otgono stopped me and told me to let him pass first. I asked him why. He replied, “I am the head of the family (Bi geriin ezen)!” I retorted, “No, your dad is!” while Otgono passed in front of me.

32This interaction represents one of the several instances when Bilgüün and Otgono tested my ignorance and deference to their knowledge. In everyday contexts, we did not observe seniority precedence upon entering and leaving the yurt. The most striking time when children were exposed to a regulated order for entering was upon formal visits, such as those paid during the lunar New Year. Older men entered first, but it was not rare for children to come in together with them, while women and young men entered in mixed order after them. In the above situation, Otgono invoked that, notwithstanding the fact that his father was back, he too was a head of the family. Justifying that he should enter first because he was head of family, Otgono tried to establish authority over me as a male person, notwithstanding his status as a child.

33In this instance, Otgono creatively explored the possibility of applying the concept of head of the family to a novel situation. I speculate that Otgono did not need to conceive of entering the home as regulated by etiquette to exploit the fact that the situation of entering a yurt lent itself to being ordered. By invoking the fact that he was the head of family, a status which in our past interactions had been associated with the fact that he received food before Bilgüün, Otgono claimed prerogatives based on social seniority. By doing so, Otgono turned the neutral fact of having to enter second or first into a socially meaningful practice, ordered by and generative of social hierarchy.

34We have seen that Otgono and Batuhan learned etiquette, through both pedagogical interactions with adults and older children, and spontaneous imitation. We have also seen how this process is intrinsically embedded within a specific material context, the yurt. As such, the material components and material actions constitutive of the domestic space contribute in and of themselves to children’s “education of attention” whereby children “apprehend directly” (Ingold 2001: 141) the domestic space as organized, and develop the sentience of their own body as constitutive of this moral space. Ingold proposes the concept of “education of attention,” in contrast with cognitive models of learning, to emphasize that a large part of learning occurs through actions of showing and direct experience. If, as Ingold states, “the forms and capacities of human beings, […], arise within processes of development” (2001: 120), it does not mean that our cognitive makeup brings nothing to this process. Conceiving of learning as a process that shapes development is not incompatible with trying to uncover mental constraints on development (Astuti, Solomon & Carey 2004) and to infer models (Strauss & Quinn 1997) that people form through their experiences.

35Earlier in this section we witnessed how Otgono used the concept of head of the family in a novel situation to generate social hierarchy. When I questioned why Otgono should enter before me, Otgono’s answer showed that he was able to mobilize instantaneously the logic of etiquette to interpret and justify his actions. Bringing all of these elements together, I suggest that etiquette is a good example of a cultural model15, which helps explaining that etiquette can both be rendered as a set of rules or code of conduct that seems given and fixed (see Humphrey 1978), and be constituted of implicit knowledge generative of new practices. In fact, as we saw, yos is not learned as a set of rules that children memorize and then replicate in identical contexts. Rather, children develop a more flexible understanding, a set of assumptions about how it makes sense to behave. They use these assumptions to interpret and act in novel situations and refine their understanding of etiquette as they are corrected and observe other people’s behaviors.

36By developing knowledge of etiquette through the ceaseless enactment of daily interactions in homes, children constitute a model of etiquette that is both personal – the product of their unique experiences – and cultural – the product of shared experiences guided through others and “afforded” (in the Gibsonian sense) by the domestic space itself as well as the sacred and mundane objects constituting it. In this sense, the yurt, its architecture, and the mundane and domestic objects that compose it constitute a moral technology. On the one hand, the processes through which etiquette is learned from others and crystallized in the very structure and objects that constitute the yurt guarantee that etiquette be re-produced from one generation to the next. On the other hand, the way etiquette is not taught as a set of rules but generatively learned and produced through practices also makes etiquette adaptable to changing historical contexts. Because etiquette is a dynamic cultural model, it can accommodate the largely different experiences of family life in which children grow up from one generation to the next.

The production of respect

37My analysis of how children learn etiquette (yos) is based on the assumption that enacting etiquette is learning etiquette. Beyond the acknowledgment that practice is knowledge (Bloch 2012: 143-185; Bourdieu 19722000; Lave & Wenger 1991), it also implies that the approach that adults take to “teaching etiquette,” or rather the process through which children learn etiquette, is an integral part of what enacting etiquette comes to mean and of the way Mongolians conceive of social relations. Anthropological studies have highlighted the role of pretend play as a preparatory stage through which children practice social skills before making use of these skills in “real interactions” (Lancy 2008: 162-5; Montgomery 2008:134-54). In their pretend play, Batuhan, Otgono and Bilguun liked to stereotype behaviors, imitating old men walking with their hands behind their back and speaking slowly, playing scenes with a mother scolding her child for not sitting correctly, using handkerchiefs as ceremonial scarves to simulate New Year greetings, etc. Children’s choices to reenact these scenes prove their salience. Children seemed particularly amused when imitating these ritualized actions and loved teaching the scenes to younger ones. This, I suggest, is linked to the fact that these practices, “being opaque” with regard to their teleological efficacy, children found them funny and thus memorable (Csibra & Gergely 2011). Let me describe just such a pretend play scene, which occurred on February 19, 2008, ten days after the beginning of the Year of the rat.Only the two brothers, Otgono and Batuhan, and I were at home. They thus felt free to play, running within the yurt in ways that they did not do in the presence of other adults.

38Otgono picked up a toy cell phone and sniffed it as if it were a snuffbottle. He then offered it to Batuhan with his right hand, his left one supporting his right elbow. Batuhan seized it, brought it toward his nose and gave it back to his brother. Batuhan then picked up a book from the table and showed me the drawing of a horse, which he started imitating by running round the stove. Otgono stopped him and got a handkerchief, which he put on his arms as if it were a ceremonial scarf. “Are you at peace?”, he asked his brother while taking hold of his brother’s head to give him a “Mongolian kiss” by sniffing his forehead. Otgono made his brother keep his arms straight with the palms up, placed the handkerchief on them, and ordered him, “Greet me ceremonially!”.

39The above interaction demonstrates that Otgono had carefully observed how adults performed ceremonial greetings during the lunar New Year visits and was able to enact ceremonial greetings in the role of an older man. Before this scene took place, as we were paying ceremonial visits to family members, Otgono had, however, refused to take the ceremonial scarf that his mother had offered him, and throughout the visits he did not enact the ceremonial greetings but simply let adults kiss him, while remaining silent. I was surprised to witness that, however concerned they were to demonstrate respect to their hosts and guests by closely observing etiquette, adults put no pressure on children to enact greetings properly. I suggest that this is due to the fact that during ceremonial occasions, and during lunar New Year visits, children were mainly interacted with as “vessels of fortune” (Empson 2011: 166) in their capacity as intrinsically virtuous persons (buyantai) to whom adults give gifts (Michelet 2018). As a result, rather than being a moment when adults insisted on them behaving as well-behaved older children, children enjoyed some of the prerogatives they enjoyed as younger kid. This has some important implications about the way children came to see etiquette and learn to enact respect. When young, during ritualized gatherings children did not experience formalized ways of interacting as a constraint, but rather as an amusing way of acting, while their attention was mainly focused on the gifts that they would receive. Only later, once children themselves wanted to affirm their status as older exemplary children, did they start enacting formalized greetings. The way children came to learn the most formalized enactment of etiquette through their own observations in circumstances when they were given gifts and explicit marks of affection by their close kin contributed to making etiquette not only the correct way but a meaningful way to show filial love (hair) and respect (hündlel).

Conclusion

40It was beyond the scope of this article to address how in the late 2000s popular foreign TV series, and the increasing accessibility of urban areas thanks to the development of roads and new sectors of activities such as mining presented people with alternative moral models to pastoral values of respect and calmness. The experiences of children growing up in a rural district of the Middle Gobi however suggests that etiquette (yos) remained an efficient moral technology in conveying and enacting these values to the next generation. I presented how through the daily and ritualized interactions within yurts, which are both spatially and socially structured through etiquette, children developed an understanding of it that they generatively applied to new situations. The way Otgono and Batuhan learned etiquette, mainly through redundant material actions, imitations and pretend plays, made it both the basis of a cross-generational shared understanding and a practice whose meaning was produced anew by the youngest generation in a changing historical context.

Bibliographie

Abu-Lughod L. 1986 Veiled sentiments : Honor and poetry in a Bedouin society. Berkeley, London : University of California Press.

Abu-Lughod L. 2008 « Writing against culture » (62-71), in T. Oakes & P.L. Price (eds.), The Cultural Geography Reader. London-New York : Routledge.

Aubin F. 1997 « Sagesse des anciens, sagesse des enfants, dans les steppes mongoles », Asie Enfance 4 : 95-113.

Aubin F. 1975 « Le statut de l’enfant dans la société mongole », L’Enfant. Recueils de la société Jean Bodin 35 : 459-99.

Astuti R., Solomon G. & Carey S. 2004 Constraints on Conceptual Development : A case study of the acquisition of folkbiological and folksociological knowledge in Madagascar (Monographs). Oxford : Blackwell.

Beffa M.-L. & Hamayon R. 1983 « Les catégories mongoles de l’espace », Études mongoles & sibériennes 14: 61-119.

Bianquis I. 2004 « Le foulard de l’accouchée en Mongolie » (49-61), in C. Méchin, I. Bianquis & D. Le Breton (eds.), Le Corps et ses orifices. Paris : L’Harmattan.

Bloch M. 2012 Anthropology and the cognitive challenge. Cambridge : Cambridge University Press.

Bourdieu P. 2000[1972] Esquisse d’une théorie de la pratique. Paris : Seuil.

Bourdieu P. 2016[1979] La distinction : critique sociale du jugement. Paris : Minuit.

Corsaro William A. 2003 We’re friends, right? Inside kids’ culture. Washington DC : Joseph Henry Press.

Csibra G. & Gergely G. 2011 « Natural pedagogy as evolutionary adaptation », Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B : Biological Sciences 366(1567) : 1149-57.

Dulam B.-O. 2006 Respect and power without resistance : Investigations of interpersonal relations among the Deed Mongols. Cambridge University of Cambridge, PhD thesis.

Empson R. 2007 « Separating and containing people and things in Mongolia » (113-140), in A. Henare, M. Holbraad, and S. Wastell (eds). Thinking through things : theorising artefacts ethnographically. London & New York : Routledge.

Empson R. 2011 Harnessing Fortune : Personhood, Memory and Place in Mongolia. Oxford : Oxford University Press.

Empson R. 2003 Integrating Transformations : A Study of Children and Daughters in Law in a New Approach of Mongolian Kinship. Cambridge, University of Cambridge, PhD thesis.

Empson R. 2012 « The dangers of excess : accumulating and dispersing fortune in Mongolia », Social Analysis 56(1) : 117-32.

Gell A. 1999 The Art of Anthropology, Essays and diagrams. London : The Athlone Press.

Ferret C. 2010 « Éducation des enfants et dressage des chevaux » (141-72), in D. Aigle, I. Charleux, V. Goossaert & R. Hamayon (eds.), Miscellanea Asiatica. Mélanges en l’honneur de Françoise Aubin. Festschrift in Honour of Françoise Aubin, Sankt Augustin, Monumenta Serica.

Henare A., Holbraad M. & Wastell S. 2007 Thinking Through Things, Theorizing artefacts ethnographically. London & New York : Routledge.

High M. 2008 Dangerous Fortunes : Wealth and Patriarchy in the Mongolian Informal Mining Economy. Cambridge, University of Cambridge, PhD thesis.

Højer L. 2003 Dangerous communications : Enmity, suspense and integration in postsocialist Northern Mongolia. Cambridge, University of Cambridge, PhD thesis.

Humphrey C. 1974 « Inside a Mongolian tent », New Society 30 : 273-5.

Humphrey C. 1978 « Women, taboo and the suppression of attention » (89-108), in S. Ardener (ed.), Defining females : the nature of women in society. London : Croom Helm [for] the Oxford University Women’s Studies Committee.

Humphrey C. 1996 Shamans and elders : experience, knowledge and power among the Daur Mongols. Oxford : Clarendon Press.

Humphrey C. 1997 « Exemplars and rules : aspects of the discourse of moralities in Mongolia » (25-47), in S. Howell (ed.), The Ethnography of Moralities. London : Routledge.

Humphrey C. 2012 « Hospitality and Tone : Holding patterns for strangeness in rural Mongolia », Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 18(1) : 63-75.

Jagchid S. & Hyer P. 1979 Mongolia’s culture and society. Boulder, Folkstone : Westview Press.

Keeler W. 1983 « Shame and stage fright in Java », Ethos 11(3) : 152-64.

Lacaze G. 2010 « Domestication du poulain et dressage de l’enfant : éduquer le corps chez les mongols » (209-221), in D. Aigle, I. Charleux, V. Goossaert & R. Hamayon (eds.), Miscellanea Asiatica. Mélanges en l’honneur de Françoise Aubin. Festschrift in Honour of Françoise Aubin, Sankt Augustin, Monumenta Serica.

Lacaze G. 2012 Le corps mongol : Techniques et conceptions nomades du corps. Paris : L’Harmattan.

Lallemand S. 2002 « Esquisse de la courte histoire de l'anthropologie de l’enfance », Journal des africanistes 72(1) : 9-18.

Lancy D. 2008 The anthropology of childhood : cherubs, chattel, and changelings. Cambridge : Cambridge.

Lave J. & Wenger E. 1991 Situated learning : Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge : Cambridge University Press.

Lemonnier P. 2012 Mundane objects, Materiality and non-verbal communication. Walnut Creek : Left Coast Press.

Malinowski B. 1932 The sexual life of savages in north-western Melanesia : an ethnographic account of courtship, marriage, and family life amoung the natives of the Trobriand islands, British New guinea. London : Routledge.

Marois A. 2006 « D’un habitat mobile à un habitat fixe. Fondements et changements de l’orientationdans l’espace domestique mongol », Études mongoles et sibériennes, centrasiatiques et tibétaines 37 : 207-237.

Mauss M. 1936 « Les techniques du corps », Journal de Psychologie 32(3-4) : 365-86.

Michelet A. 2016a « What Makes Children Work ? The Participative Trajectory in Domestic and Pastoral Chores of Children in Southern Mongolia », Ethos 44(3) : 223-247.

Michelet A. 2016b « Owning by giving Gift-giving, Learning kinship and the reproduction of social hierarchy during Mongolian New Year celebrations », Annales de la Fondation Fyssen 31 : 45-59.

Michelet A. 2015 « Why are Mongolian Infants Treated Like ‘Kings’? », Inner Asia 17(2) : 273-292.

Montgomery H. 2008 An introduction to childhood : anthropological perspectives on children’s lives. Chichester UK, Malden MA : Wiley-Blackwell.

Myers F. 1988 « The logic and meaning of anger among Pintupi aborigines », Man 23(4) : 589-610.

Novgorodova E. & Luvzanzav C. 1971 « Salutations mongoles traditionnelles », Études mongoles & sibériennes 2 : 134-44.

Ruhlmann S. 2015 L’appel du bonheur. Le partage alimentaire mongol. Paris : Nord-Asie 5.

Ruhlmann S. 2010 « Les rites de naissance chez les Mongols Halh » (225-47), in D. Aigle, I. Charleux, V. Goossaert & R. Hamayon (eds.), Miscellanea Asiatica. Mélanges en l’honneur de Françoise Aubin. Festschrift in Honour of Françoise Aubin, Sankt Augustin, Monumenta Serica.

Strauss, C., & Quinn, N. 1997 A cognitive theory of cultural meaning. A cognitive theory of cultural meaning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sneath D. 2000 Changing Inner Mongolia : pastoral Mongolian society and the Chinese state. Oxford : Oxford University Press.

Warnier J.-P. 2007 The Pot-King. Leiden, Boston : Brill.

Notes

1 Countryside (hödöö) is a relative concept. Expressed in reference to Ulaanbaatar, the rest of Mongolia can be designated as countryside. Expressed in reference to district centers, countryside refers to the areas where mobile pastoralists live with their herd.

2 The modest interiors characteristic of dwellings in the countryside contrast with the more heavily furnished and decorated interiors of yurts and houses in the village. See High (2008: 101-20) on how herders manage the public display of their wealth; see Empson (2011: 268-316; 2012: 128-9) on the social tensions created by the accumulation of wealth and its conspicuous display in villages.