- Accueil

- Numéro 1

- Carnets de visite

- Memories of a visit to UFRJ's National Museum (Brazil): narratives of an experience and perspectives on reconstruction

Visualisation(s): 4206 (6 ULiège)

Téléchargement(s): 53 (0 ULiège)

Memories of a visit to UFRJ's National Museum (Brazil): narratives of an experience and perspectives on reconstruction

Document(s) associé(s)

Version PDF originale1Rio de Janeiro, Quinta da Boa Vista, August 29th, 2018. After a morning of discussions in an academic event, I dedicated my afternoon to visiting Brazil's oldest museological institution: the UFRJ's National Museum. During the nineteenth century, its main building was the Brazilian imperial family's residency and then the headquarters of the first Constituent Assembly after the Proclamation of the Republic (1889). I went through hallways and rooms; there were full of children and teenagers. Judging by their facial expressions, they were fascinated to see dinosaur fossils, "monstrous" animals, but also indigenous artifacts, pieces of a city sadly known to have been destroyed by a volcano – Pompeii; and finally, the main attractions, the Egyptian mummies. At that temple of knowledge, Brazilians were not only in contact with national riches but also with icons of worldwide culture. The museum was one of the few spaces in such a vast country where it was possible to see artifacts of the societies of Universal History. However, everything would change four days later.

2

3On September 2nd, 2018, a casual Sunday, the National Museum opened its doors at 10 am. Parents took their children to visit the attractions; employees carried out their functions of orientating the public, cleaning the space, explaining the meaning of the artifacts, and making sure that everything was in order. At sunset, around 5 pm, the museum closed its doors and, consequently, went into a waiting state until the restart of its routines the next day. Its next journey, however, would be completely different. At 7:30 pm on that same Sunday, Brazil's biggest nightmare became a reality: the destruction of the institution's main headquarters by an uncontrollable fire.

4

Figure 1 – Main building of the National Museum, four days before the fire. Photo: André Onofre Limírio Chaves.

5The flames drastically destroyed each section of the Museum that occupied the old palace's area. The former Palace of São Cristóvão gradually turned into a grand ruin. The fire lasted for over six hours, all the efforts and investments that had been difficult to achieve turned to ash. On that fateful evening, Brazil lost one of its most important scientific institutions and the memory of various nations.

6

7On the painful morning of September 3rd, 2018, Brazilians, including me, and the whole world would see what was left of what had been the home of the biggest museum in Latin America: ashes and ruins. Still today, it is difficult to point the culprit.1 At first, the media and the federal government accused the employees of being responsible for the museum's conditions. However, from the director to the security guards, all the employees were more victims than culprits after years of battle and alerts surrounding the negligence by the State of Brazil concerning the institution's maintenance.

8

9In the yearly reports of the National Museum, diverse observations citing the urgency of more significant investments for the institution were notorious. That fact did not pertain only to the twenty-first century. In the 1800s, the need of money for emergency repairs that put the integrity of rooms and the collections at risk already evidenced itself. This only shows that the priorities of the monarchical and republican governments were elsewhere, and that Brazilian science and culture have always been cast aside, surviving through scarce financial resources and intense dedication of researchers and employees.

10

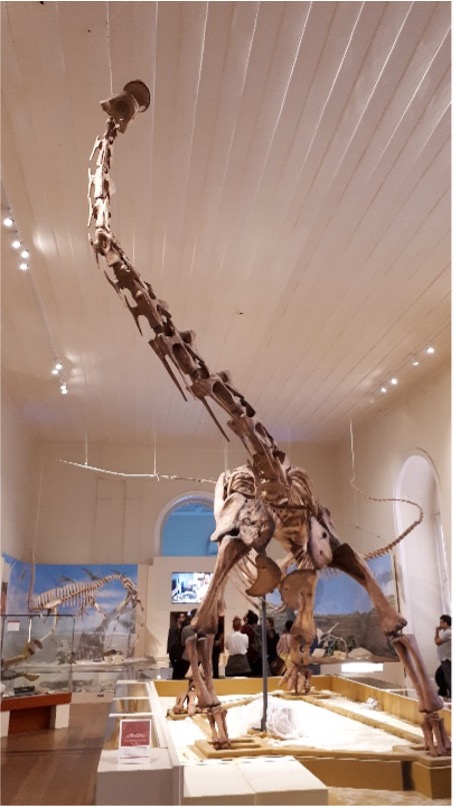

Figure 2 – Interior of the Museum, Paleontology section, highlighted an example of Giant sloth’s (Glossotherium). Photo: André Onofre Limírio Chaves.

Figure 3 – Paleontology section, highlighted, the reconstitution of the fossil of Maxakalisaurus topai. Photo: André Onofre Limírio Chaves.

11The institution was created in 1818 by the Portuguese monarch D. João VI under the influence of the princess and future empress of Brazil, D. Leopoldina of Habsburg, who had great affection for naturalist practices, having herself a cabinet of Natural History inside the palace. Both saw the necessity of having an institution on the Brazilian soil dedicated to exploring the natural riches of its extensive territory. After Independence (1822), the National Museum2 continued to act as a scientific apparatus that should study the Brazilian flora and fauna and the native indigenous societies of its territory. The importance of the scientific space, beyond the produced research, was to become a relevant repository of specimens of the natural American world and the material culture of various Brazilian indigenous societies, many of which no longer exist.

12

13To visit the National Museum was an experience in which the visitors turned off the external world and traveled through various parts of the world and temporalities. At the institution's entrance, the Bendegó meteorite was exposed, the biggest of its category found in Brazil, and impressed visitors because of its 5.36 tons. There were sections dedicated to the meteorite studies, highlighting the importance of the institution's collection in this particular field of research. After climbing a majestic staircase, curious visitors would arrive at the paleontology section, where they were greeted by a natural-sized reproduction of the Giant sloth's fossil (Glossotherium), an important specimen in the memory of those who visited the space.

14

15In the other rooms, the public could engage with the diverse fields of study in Natural History, such as Anthropology. Many rooms showed the importance of the study of living beings, mainly ones of the Brazilian. The section dedicated to Entomology was a favorite of the visitors, having its great crowd of curious spectators, who observed the richness of insect specimens found in Brazil that drew attention to their size and color, such as the butterflies and grasshoppers.

16

Figure 4 – The Sha-Amun-En-Su coffin, given as a gift by the Egyptian government to Emperor D. Pedro II, at the end of the 19th century. Photo: André Onofre Limírio Chaves.

17The Archeology sections were probably the ones that most fascinated visitors because, in them material culture from famous societies of Universal History, such as the Egyptians, Greco-Roman, Etruscans, and Incas, were found. The Egyptian collection became famous as it was the oldest and most important examples of Egyptian antiquities in Latin America, having been acquired between 1826 and 1827. This set, to which I dedicate special attention, was my object of study during my master's course, that coincided with the fire at the institution. Interestingly, I was precisely reading the Museum's documents from the nineteenth century that reported the neglect from public organs when I heard a scream, "the National Museum is on fire!". It was here that my nightmare began.3

18

19The "stars" of the Egyptian collection were the human and animal mummies, especially cats, which fed the imagination of visitors that had the desire to know the mummification techniques of the ancient Egyptians. In the mind of a great part of Brazilians who visited the institution, this space materialized an ideal of a museum and cultural institution that could be seen only in the Old World, on the Internet, or a great deal in Hollywood films.

20

Figure 5 – Pre-Columbian Archeology Section. Photo: André Onofre Limírio Chaves.

Figure 6 – Brazilian Anthropology Section. Photo: André Onofre Limírio Chaves.

21After leaving the Egyptian Room, the visitor would find a world of traces left from the Mediterranean past, especially relics from the cities buried by the eruption of Vesuvius (79 a. D). Whoever passed through this section destined various minutes of their visit to look at the details of ceramic vases and other objects that impressed with their color contrasts and the motifs of mythological scenes. Another grand attraction was the frescoes from the Temple of Isis, in Pompeii, that arrived in Brazil as a gift to the Italian-born empress Thereza Christina of Bourbon. This present brought a bit of her country's past to Brazil. After this trip through Ancient History, the visitor would fall into another universe: that of the Pre-Columbian antiquities. In the rooms dedicated to this material production, it became evident how rich and important the culture of Latin America's inhabitants was before contact with the Europeans.

22

23Other treasures of the National Museum were scattered in different rooms, such as the oldest human remains of the Americas: the bones of Luzia. They were found in the city of Santa Luzia, in the state of Minas Gerais, and gained international importance because of their morphology and dating. After the fire, it was believed that Luzia had turned to ashes, but, as a symbol of Brazilian resistance, she "survived." The recovered bone fragments suffered some damages but were recovered, representing a sigh of relief for many researchers and Brazilian society.

24

Figure 7 – Plafond of the Throne Room from the period when the National Museum building housed the imperial family. Photo: André Onofre Limírio Chaves.

25After passing through the room in which Luzia could be found, we would come across the Brazilian Archeology section in which ceramic work of diverse indigenous tribes was exposed and gave an impression of the mastery of the material production of these societies which inhabited the nation. Fortunately, as another symbol of resistance, the indigenous ceramics were saved from the ruins, some almost intact, although others show signs left by the destruction. Its survival reinforces the resilience of Brazilian indigenous tribes in their battles of the past and present. Unfortunately, the Ethnology collection, with its accessories, comprised of artifacts of organic origin, such as plumage, wood, and seeds, were majorly destroyed.

26

27After crossing the world of Archeology and Anthropology, visitors would arrive in one of the main parts of the museum: the historic rooms, two spaces of the institution that referenced its palatial aspect up until the moment of the expulsion of the imperial family at the end of the nineteenth century. These two spaces were the Throne Room and the Diplomats Room. In these locations, the emperors and empresses received foreign entourages and representatives of Brazilian society. The decorative details drew the attention of all that entered. Here, the public made an imaginary return to Imperial Brazil, viewing the environment where the only monarchy of the Americas was located. A small part of the memory of the first inhabitants of the São Cristóvão Palace was exposed in these two rooms, reminding the visitors that, before becoming a museum, the building had been the stage for important decisions in Brazilian history.

28

Figure 8 – Zinkpo (a type of throne) that belonged to the seventh king of Dahomey, Adandozan, in the Kumbukumbu exhibition at the National Museum. Photo: André Onofre Limírio Chaves.

Figure 9 – Archaeological ceramics of Brazilian indigenous rescued from the ruins of the National Museum in the exhibition “Arqueologia do Resgate” (CCBB- Rio de Janeiro), 2019. Photo : André Onofre Limírio Chaves.

29Lastly, the visit would continue through the indigenous collections with the variety and quality of the objects produced by various ethnicities. Consequently, the tour finished in a room that allowed a trip to the African continent4, showing artifacts from different countries of this important continent. This section was relevant to reinforce the national memory about the enslaved Africans' descendants that, for many years, were neglected. Beyond that, this room dedicated to the African memory and the Afro-descendants had been inaugurated a short time ago, through a decolonial perspective that gave voice to the African people enslaved during the construction of the Brazilian past.

30

31The entire microcosm of knowledge underwent a metamorphosis after the fire. A great deal of the archives, about twenty million pieces, was transformed into something new, the majority into ashes and charcoal. While the others, if they were not destroyed, suffered from the high temperatures, with the water, and the successive collapses. In an arduous task of reconstruction and resistance, the National Museum team is working intensely to rescue the collection that survived these events. So immeasurable is the commitment to giving back to society a new institution with events, projects, and expositions made through the months following the disaster, such as the exhibits of Arqueologia do Resgate (Archeology of Rescue) in the Cultural Center of Banco do Brasil. In this exposition, many objects saved during and after the fire were showcased. Curiously, the exhibit had a high number of visitors, showing that Brazilian society is interested in seeing the institution rebuilt.

32

Figure 10 – Public visiting the exhibition “Arqueologia do Resgate”. Photo: André Onofre Limírio Chaves.

33After the fire, it was believed that almost all the museum and its collections were destroyed. However, a great part of the society did not know of the other annexes that were not inflicted by the flames, such as the Horto Botânico (Botanical Garden) – the repository of one of the most important herbariums of Brazil, with an archive that was continually expanded since the nineteenth century. The Library of the National Museum, with its rare archive and other annexes with the collections of invertebrates and vertebrates, were intact. Far from the fire, these locations contain important collections about the Brazilian fauna and flora, reinforcing the need to reconstruct the main building of the National Museum. However, it is not only the collections which suffered from the destruction of the main physical space of the institution; many researchers had to interrupt their work. Consequently, they had to rethink their theses, dissertations, and other research. The help from other museums, national and international, was critical for these academics to give continuity to their studies. Knowledge and scientific practices did not succumb to the flames.

34

Figure 11 – Greco-Roman ceramics from the Thereza Christina collection recovered from the ruins of the National Museum, in the exhibition “Arqueologia do Resgate”. Photo: André Onofre Limírio Chaves.

35Nowadays, Brazil is going through difficult times. The federal government, characterized by far-right ideologies, uses ignorance as a tool to attack scientific work made by Brazilian researchers. Society is watching indigenous people and the Amazon rainforest being brutally attacked, as well as public universities and their museums, such as the National Museum. Nevertheless, the fire of the National Museum gains a double sense at this moment. The first is to watch a significant portion of the prominent scientific institution of the country turn to ashes, and, with that, Brazilian and worldwide history being destroyed by the absence of care of leaders regarding the protection of the memory and the fomentation of Brazilian science for its potential in developing the nation. The second is to perceive this destruction as a failure in the development of a national building that, sadly, demonstrates that the Brazilian population lacks memory locations as essential places for identity building.

36

37The culprits of the National Museum fire will appear in the future. At this moment, Brazilian society and public administration need to dedicate themselves with the utmost commitment in the inspection and the adequate financing of the activities of other areas of the nation's memory so that disasters such as this one does not happen again. Unfortunately, only time will tell what will happen to the National Museum. The rebuilding will be slow, as well as healing of the institution memory and its archives. Beyond that, profound conceptual studies will be necessary to tell us what the new narrative will be that is constructed by this microcosm of sciences, Brazil's history and its place in the world.

38

39National Museum Lives!!

40Belo Horizonte, August 14th, 2019

41

42Epilogue

43

44Unfortunately, in June 2021, the Museu de História Natural e Jardim Botânico da UFMG (Museum of Natural History and the Botanical Garden of the Federal University of Minas Gerais) suffered a terrible fire in its technical reserve. Pitifully, there were many losses, but not comparable to the volume lost at the National Museum. Still, museums and other memory harbors in Brazil continue to suffer casualties. Now, the Cinemateca Brasileira (Brazilian Cinematheque), which maintains the memory of Brazilian filmographic production, is at great risk of being destroyed because the federal government has abandoned the institution, leaving it at the mercy of neglect. The alert has been sent. For how long should we continue to live with this museum negligence?

45

46Belo Horizonte, June 4th, 2021

47After a month later….

48

49Again, Brazil lost an important part of its history. On July 29, 2021, a fire hit one of the warehouses belonging to the Cinemateca Brasileira, destroying important audiovisual and document collections. Since the end of 2020, the institution does not have managers, as the federal government has not shown interest in avoiding this disaster. There is no doubt that the destruction of Brazilian culture and science is a project of the Bolsonaro’s government. And regrettably he is succeeding.

50

This paper was written in the year 2019, less than one year after the fire, during a period of recovery at the National Museum of UFRJ. As the COVID-19 pandemic had not yet occurred, the author has chosen to make small alterations to the narrative, giving it a marked temporality.

Notes

1 After the Federal Police’s investigation, the cause of the fire was revealed: an electrical malfunction in the Museum auditorium’s air conditioner.

2 In the beginning, the institution was called Museu Real (Royal Museum), then being referenced as the Museu Nacional Imperial (Imperial National Museum). Initially, its building was in another location in Rio de Janeiro, at the former Campo de Santana, now Republic Square. At the end of the 19th century the institution moved to the former Palace of São Cristóvão, after the exile of the imperial Family.

3 After a period of mourning, I managed to complete my master’s studies on the history and memory of the National Museum’s Egyptian collection. Beyond the research done, the documentation that I digitized was donated to the institution, as a way of recomposing the SEMEAR (Memory and Archive Section of the National Museum). That is why it is so important that museums and archives allow researchers to photograph the documentation. Chaves André Onofre Limírio, 2019 : Do Kemet para o Novo Mundo: o colecionismo de antiguidades egípcias no Brasil Imperial, Dissertação [mestrado], Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonten, Fafich. Available on: https://repositorio.ufmg.br/handle/1843/33372#:~:text=Reposit%C3%B3rio%20UFMG%3A%20Do%20Kemet%20para,Brasil%20Imperial%20(1822%2D1889).

4 This was the path that I used to take when I visited the institution, which had other trajectories of visitation, depending on the visitor’s needs. That being said, the route I described was the one I always liked to take.