- Accueil

- Numéro 2

- Carnets de visite

- Ecomuseo Casilino Ad Duas Lauros: a new life in south-eastern Rome

Visualisation(s): 1845 (4 ULiège)

Téléchargement(s): 47 (0 ULiège)

Ecomuseo Casilino Ad Duas Lauros: a new life in south-eastern Rome

Document(s) associé(s)

Version PDF originaleTable des matières

1

Figure 1 – Logo of the Ecomuseo Casilino Ad Duas Lauros. Photo: Ecomuseo Casilino Ad Duas Lauros.

2

3The Ecomuseo Casilino Ad Duas Lauros1 is an ecomuseal project that was born in 2009, which extends into an area of Rome where the need of citizens to regain possession of their territory seemed undeniable. The project originates as a reaction to the decision of the Roman city council, which wanted to revoke the landscape constraint2 current in the Casilino area3. The decision, made by the Capitoline administration, proposed the launch of a building program in the area, not caring about the historical, cultural but also emotional value present in the area. Supported and assisted by the mayor of Rome, building speculation was a real threat: through numerous local assemblies and meetings, the reaction takes the form of a real protest, involving the community of citizens of the districts of Tor Pignattara, Casilino 23, and Villa Gordiani, included in the current Municipality V of Rome. The story - as Claudio Gnessi states - the current director of the Ecomuseo Casilino, acquired such great resonance that it went beyond regional borders. The intense media action, especially thanks to social networks, allowed the protest to circulate on the national media, not only giving a great voice to citizens but grafting in them a spirit and a desire for a change, which goes beyond protest alone: this is how the idea of creating an urban ecomuseum was born.

4

1. Historical Background

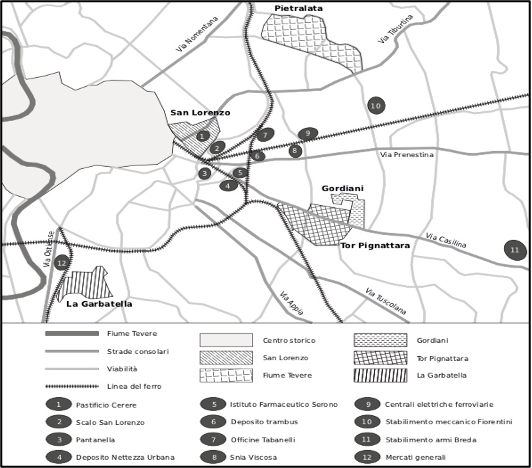

5The neighbourhoods included in the reference territory of the Ecomuseo Casilino, have recorded human activities since ancient times, as evidenced by the numerous archaeological sites and cemetery areas. As Stefania Ficacci4 states, the area was always largely anthropized due to the healthiness of the air and during the medieval period it became an agricultural area. In 1800, the countryside acted as a passage for the farm labourers coming from Colli Albani5. With the industrial revolution, the area rapidly changed its appearance: from a rural reality that had persisted for centuries, the territory was transformed into an urban and industrial environment. The new industrial poles were located in a concentrated manner in the south-eastern outskirts of Rome (fig. 2) and welcomed the great migration flow that occurred at the time, coming firstly from the Roman countryside, then from the neighbouring regions and from southern Italy.

6

Figure 2 – Map of the industrial pole in south-eastern Rome. Photo: Stefania Ficacci.

7

8The urban reality gradually incorporated the countryside: Pigneto, Mannarella, Centocelle, Quadraro and Tor Pignattara became consolidated urban settlements characterized by massive building construction. The migrant family units who arrived in the neighbourhood, had the possibility of obtaining low-cost houses, simply by building their own home. From this process, in addition to the massive construction, a heterogeneous urban reality emerged, which does not coincide with the “Romanity”6 of the suburbs, but which consists of a population made up of different cultures of origin (Ficacci 2017, p. 95).

9

10The neighbourhoods, in particular that of Tor Pignattara, then welcomed a second migration at the end of the twentieth century, mainly composed of Asians, in particular Bangladeshi. After the demographic depletion of the 1970s-1980s, this community managed to fit into the economic and social dynamics of the neighbourhood, playing a redeveloping role, which brought new vitality to the area.

11

12Today these neighbourhoods also host students and young people, attracted by the culturally and socially active reality of the area, which manifests itself in neighbourhoods such as Pigneto or the eXSnia social centre.

13

14Therefore, the territory presents itself as a culturally stratified system, made up of recent and secular migrations, of people who coexist and live the territory, redefining the socio-cultural identity of the neighbourhood. It is in these dynamics that the Ecomuseo Casilino operates, creating meeting points between the different communities and involving them in a collective, active and participatory way.

15

2. Making the Casilino ecomuseum: planning and methodology

16Behind the origin of the Ecomuseo Casilino, there is a promoting group which for years has outlined the ways to develop, implement and manage the project: In 2011 the proposal of the establishment of the Ecomuseo Casilino Ad Duas Lauros was accepted by the Municipality V of Rome. A year later, the museal project was formalized and the Association for the Ecomuseo Casilino Ad Duas Lauros was born. In 2019 the Ecomuseo Casilino was recognized by Lazio Region as an Ecomuseum of regional interest.

17

18The first stages of the project were based on the work of the scientific committee, which was in charge of the preliminary research concerning the organization and definition of the project prospects, as well as the collection of information and sources. At the same time, collective meetings were held within the community and the support of the scientific committee, to understand all aspects concerning the heritage present in the Casilino area. This process allowed citizens to rediscover their own territory, the importance of protecting green spaces and social spaces, but above all identifying those elements of the heritage that were invisible to their eyes a short time before (Murtas 2009, p. 154-155)7.

19

20In 2015, thanks to the victory of the Acea tender for Rome, the Ecomuseo Casilino received funding that allowed it to carry on numerous projects, including participatory laboratories. The latter was particularly useful, as they made it possible to listen to citizens first-hand, creating an environment for debate and participation, also using the method of community mapping. The workshops were structured in two fundamental points: firstly, the mapping of the territory was carried out, highlighting those considered as characteristic elements; subsequently, the preliminary work of census of the existing sources was deepened. During the workshops, S. Ficacci explains that a process of “negotiation with the community” takes place, which is a reciprocal exchange of sources, between the professionals and the community itself. Substantially, identifying and identity elements of the territory are chosen, which are placed in comparison with those considered as such by the community, in order to identify the resources to be used in the ecomuseum. This procedure allowed S. Ficacci to reconstruct the historical landscape, analysing and comparing his research with the private memories of the participants. It is worth dwelling on this point: the scarcity of documents relating to these neighbourhoods has led researchers to draw on other sources, such as documents of religious congregations, educational institutions, but especially the memories of the inhabitants. These memories have been received both as written testimonies (autobiographies, diaries) but especially as oral testimonies: in this case, the oral source becomes an indispensable element in the research for the reconstruction of a community’s cultural heritage, as well as for historiographical reconstruction (Ficacci 2017, p. 98-99)8.

21

22The confrontation with citizens has not only allowed the community to rethink its own territory but also provided researchers with a broader reading of the sources and a new research methodology. In this way, you can enter the way of thinking and living that territory, and how it manages to connect people and places, past and present.

23

24All the activities mentioned above, and therefore the ecomuseum activities, are conducted publicly, in a participatory and democratic way, to be accessible and understandable to anyone. Therefore, the ecomuseum develops specific activities for the involvement of all segments of the population.

25

26From working on the participatory workshops, the percorsi dell’Ecomuseo Casilino were created, which are paths or routes that correspond to the tangible and intangible heritage of the territory and that represent a form of narration and use of the Ecomuseum.

27

3. The territory and the paths

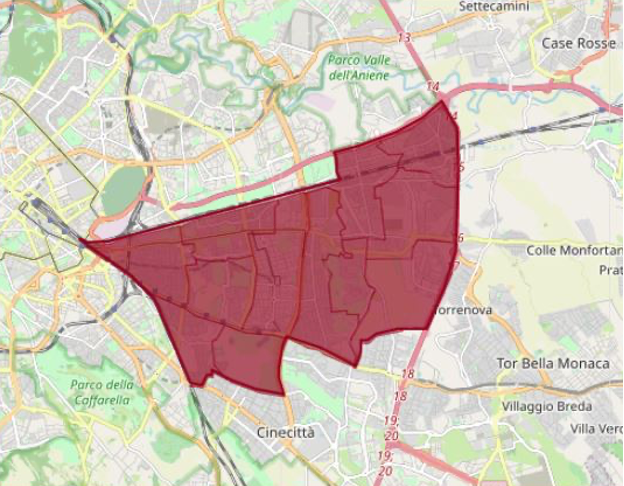

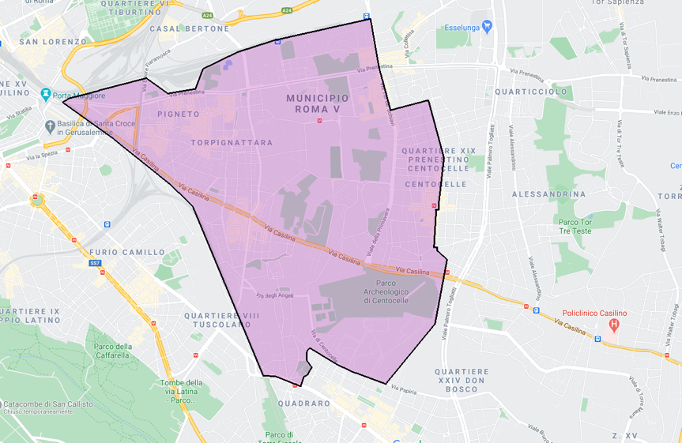

28The Ecomuseo Casilino Ad Duas Lauros is located in the south-eastern area of Rome, inside the Municipality V (fig. 3), and covers a segment of Roman territory that extends from east with Porta Maggiore to west with via Tor de' Schiavi (Centocelle area), and from south with the Centocelle Archaeological Park to north with Villa Gordiani. The area covered by the work of the ecomuseum (fig. 4) also includes the area of the former Snia Viscosa, the park of Centocelle and all those neighbouring areas that present a form of “natural contiguity”, from a social, archaeological and urban-landscape point of view.

29

Figure 3 – Municipality V of Rome. Photo: Carte in Regola.

30

Figure 4 – Area of the Ecomuseo Casilino. Photo: Giulia Gullì.

31

32The Percorsi is a project that was created to outline the ecomuseum itineraries, born from the work on community mapping. As already mentioned above, the project is an innovative proposal for the fruition and narration of heritage, which is based on information and on the involvement of citizens, and which aims to enhance the territory. The paths outlined are configured with six main themes characteristic of the Casilino area: the anthropological path, the archaeological one, public art, cinema, the contemporary historical path and the landscape one, and finally the path of spirituality.

33

34The percorso antropologico or anthropological path develops in the form of a narrative walk, engaging oneself in the life of the neighbourhoods and coming into direct contact with the local protagonists. The aim is to return a reliable and not simplistic image of the territory that is very often object of prejudices and stereotypes.

35

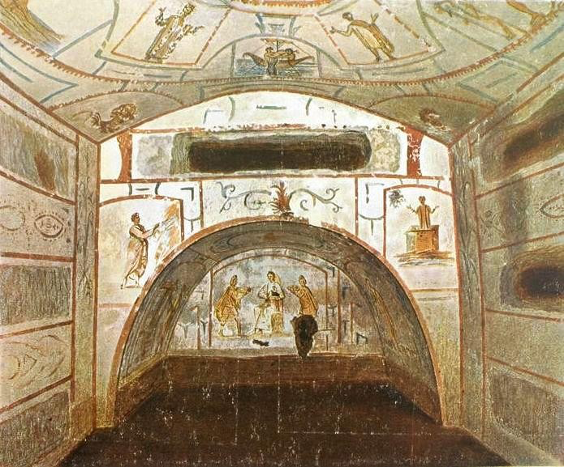

36The percorso archeologico or archaeological path extends both in an urban and natural environment, thanks to the numerous parks present. Town Hall V is one of the Roman municipalities with the most areas and archaeological remains. Unfortunately, the dense urban context tends to obscure these areas, which with this path the Ecomuseo Casilino tries to enhance, transmitting the archaeological importance as a vestige of the past. At the same time in some areas it is interesting to note the coexistence of archaeological elements juxtaposed with contemporary buildings, such as the stretch of the Alessandrino aqueduct that runs through the Giordano Sangalli Park (fig. 5-6). The project focuses in particular on the archaeological area of the archaeological district Ad Duas Lauros, the archaeological-museum complex that includes the Mauseoleo di Sant'Elena (fig. 7) from which the district of Tor Pignattara takes its name9, and the catacombs early Christian of SS. Marcellino and Pietro (fig. 8). The purpose of the ecomuseum project is not only to disseminate it, but also to arouse the interest of the community and visitors concerning the archaeological heritage.

37

Figure 5 – Alessandrino aqueduct in Giordano Sangalli Park. Photo: Giulia Gullì.

38

Figure 6 – Alessandrino aqueduct and private apartments from the Giordano Sangalli Park. Photo: Giulia Gullì.

39

Figure 7 – Mauseoleo di Sant’Elena (Saint Elena Mausoleum). Photo: Giulia Gullì.

40

Figure 8 – SS. Marcellino and Pietro catacombs. Photo: Ecomuseo Casilino Ad Duas Lauros.

41

42One of the main features of these neighbourhoods is the vast presence of mural art: the percorso d’arte pubblica or public art path is represented by the street art museum10, a real open-air museum. C. Gnessi explains how an embryonic form of this type of art was already present in the 1980s, as merchants accepted the challenge of painting the shutters of their shops. Today, the Ecomuseo Casilino does not directly deal with the production of street art forms, but with the search of consents for their realization. This is how Millenials (fig. 9) by the artist Mp5 was born, five classically inspired caryatids that coexist with the urban environment. The concept of coexistence and coexistence is also present in Melting Faces § Stories § Discritct (fig. 10) created by the artists David Vecchiato, Nicola Alessandrini and Lucamaleonte, in the heart of Tor Pignattara. The work represents the reflection of that neighbourhood: three faces, one of Italian origin, one of Bangladeshi origin and one of Chinese origin. The title of the work refers to the mixing and “fusion” of faces, hence the stories and cultures present in the neighbourhood, made up of different immigrants and cultural stratifications. The work was not only based on creative flair but involved a preliminary research phase, in which the three artists went to three families who inspired this project.

43

Figure 9 – Millenials by Mp5. Photo: Giulia Gullì.

44

Figure 10 – Melting Faces § Stories § Discritct by David Vecchiato, Nicola Alessandrini and Lucamaleonte. Photo: comuseo Casilino Ad Duas Lauros.

45

46Cinema is another very important theme for the neighbourhood, which mainly interested Neorealist cinema, given the somewhat stereotyped vision of the Roman suburb. The percorso del cinema or cinema path, however, is also a tool for understanding the territory: The Ecomuseo Casilino collaborated with the Lodovico Pavoni primary school in Tor Pignattara, with the cinema maps project, a work where children were invited to identify those places corresponding to the setting of films, such as Roma Città Aperta, where numerous scenes are shot in their neighbourhoods. The ecomuseum has managed to adapt each activity to the needs of each member of the population: in this case, children have learned to associate certain emotions with certain places and learn something more about the neighbourhoods they live in.

47

48With the percorso della storia del ‘900 or path of the history of the 1900s, we retrace the events of these neighbourhoods, which have been the scene of numerous events over the last century. The goal is to develop a reflection on historical places. Inciampi nella memoria is a project that was created to remember the places of the raids and deportations of the Nazi-Fascist police, and is manifested by the “stumbling blocks” of small installations spread throughout the urban environment.

49

50The percorso sul paesaggio or path on the landscape, in addition to including the urban districts, takes into account the natural areas present. The area covered by the ecomuseum has resources not only in urban planning, but also in landscape: in addition to the parks, it is not difficult to walk between Centocelle and Tor Pignattara, and be transported into what appear to be small countryside areas, objects of visits and laboratories.

51

52In such a complex and culturally stratified reality, such as that of these neighbourhoods, a percorso sulla spiritualità or path on spirituality was also planned. The coexistence of communities of different origins has inevitably led to the coexistence of different religions: in these neighbourhoods it is normal to find a Christian church close to a mosque or a Buddhist centre. The path, in this case, aims to enhance religious pluralism, putting the different religions and the different systems of values in direct contact. On the other hand, the project seeks to break down stereotypes resulting from media and political exploitation.

53

4. Contributions of the Casilino Ecomuseum to the territory

54The Casilino Ad Duas Lauros Ecomuseum is a project that has found place and has taken root in neighbourhoods which for a long time were considered difficult to recover. As C. Gnessi states, the ecomuseum has managed to “give a positive meaning to an area that media exploitation was handing over to the universe of degradation at risk of banlieu.” (gnessi 2017, p. 35). The prospect of active and participatory protection of the widespread urban heritage has made it possible to undertake processes that have redeveloped the territory, making it more alive than ever. This is because the project was able to identify the characteristic elements that the territory and the community alone could not fully exploit. Today the neighbourhoods included in the ecomuseum represent a living point for Rome, both from a cultural and social point of view, which manages to reconcile urban life, of “cities”, with that of neighbourhoods made up of small communities that live together where community’s spirit is still felt. The Ecomuseo Casilino managed, thanks to numerous initiatives, to awaken that sense of community and tolerance that was slowly fading. It is no coincidence that the area has become a reference point for many young Romans, tourists, researchers and scholars.

55

56The project today represents a successful socio-cultural investment, which even in the last year has not been discouraged by the pandemic crisis: the transparent and intuitive website, and the social networks, represent a great digital investment that has allowed the Ecomuseo Casilino to carry out numerous projects without ever losing contact with the community.

57

Bibliographie

Broccolini Alessandra, 2017: « Patrimonio e mutamento a Tor Pignattara/Blanglatown. Voci dai nuovi e vecchi abitanti », in Broccolini Alessandra & Padiglione Vincenzo, Ripensare i margini. L’ecomuseo Casilino per la periferia di Roma, Aracne editrice, p. 161-193.

Ecomuseo Casilino Ad Duas Lauros, available on: https://www.ecomuseocasilino.it/.

Gnessi Claudio, 2017: « Dalla protesta alla proposta. Per una genesi del progetto dell’Ecomuseo Casilino Ad duas Lauros », in Broccolini Alessandra & Padiglione Vincenzo, Ripensare i margini. L’Ecomuseo Casilino per la periferia di Roma, Aracne editrice, p. 35.

Ficacci Stefania, 2018: «I l quartiere di Tor Pignattara a Roma. Un case-study di storia urbana per la realizzazione di un ecomuseo urbano », in Bertoni Angelo & Piccioni Lidia, Raccontare, leggere e immaginare la città contemporanea, Olschki édition, p. 105-112.

Ficacci Stefania, 2017: « Le fonti orali come metodologia di ricerca per la ricostruzione di un patrimonio culturale comunitario. Il case-study dell’Ecomuseo Casilino a Tor Pignattara », Proposte e ricerche, n° 78, p. 87-100.

Ficacci Stefania, 2013: « Tra mestiere e quartiere. La classe operaia romana alla ricerca di un’identità », in Zazzara Gilda, Tra luoghi e mestieri. Spazi e culture del lavoro nell’Italia del Novecento, Edizioni Ca’ Foscari, p. 81-104.

Ficacci Stefania, 2018: « Co.Heritage, memorie d’inciampo. Un progetto di Public History per la valorizzazione del patrimonio culturale del V Municipio di Roma », oral, communication, 2th conference AIPH, Pisa.

Murtas Donatella & Davis Peter, 2009: « The role of The Ecomuseo Dei Terrazzamenti E Della Vite, (Cortemilia, Italy) in Community Development », Museums and Society, n° 7, p. 150-186.

Notes

1 The Latin name Ad Duas Lauros means “between the two laurel plants”. The term comes from the ancient imperial fund of Constantine, which today corresponds to the Comprensorio Casilino.

2 It refers to the Ministerial Decree 21 October 1995, Law number 431 emitted by MIBACT.

3 The comprensorio Casilino consists of a large strip of unconstructed land.

4 Besides being an historian, Stefania Ficacci is vice president of the Ecomuseo Casilino. Thanks to her historiographical studies, especially focused on the Tor Pignattara district, she provides us detailed information on the past of the south-eastern districts of Rome.

5 Colli Albani is an area of hills located on the east part of Rome.

6 Stefania Ficacci deepens the question by talking about the “Romanity” advocated by Neorealist films: it represented only a part of the population of these neighbourhoods and was not an all-encompassing element.

7 In her research for the Ecomuseo dei Terrazzamenti e della Vite in Cortemilia, Donatella Murtas explains how citizens take into account only a part of their heritage: in the case of Cortemilia, for example, most of the community connected only the main church of the town to the heritage concept.

8 As already mentioned in the previous notes, these neighbourhoods have been the object of a stereotyped vision, the result of a “previous literature that has interpreted this neighbourhood as an example of a suburb born illegally, making an erroneous example of a Roman suburb”. Oral sources have made it possible to break down these stereotypes, allowing both the community and researchers to rediscover the past and its values.

9 During Middle Age the masouleum of Sant’Elena was called “Tor delle Pignatte”, because anphorae were used to lighten the load of the dome.

10 The museum of street art is composed by three main poles: the Pigneto street art museum, the Quadraro museum and the Tor Pignattara museum.