- Accueil

- Volume 28 (2025)

- number 1-2

- The latest Devonian (Famennian) phacopid trilobite Omegops from Belgium

Visualisation(s): 1216 (17 ULiège)

Téléchargement(s): 657 (10 ULiège)

The latest Devonian (Famennian) phacopid trilobite Omegops from Belgium

Abstract

The Strunian regional substage corresponding to the uppermost Famennian of Belgium and northern France (Avesnois area) is marked by the occurrence of trilobites after an almost complete absence that began at the top of the Frasnian. The Strunian phacopid trilobites represented by Omegops, i.e., O. accipitrinus and O. maretiolensis, are recorded and illustrated from two Belgian sections (Spontin and Chansin) situated in the central part of the Dinant Synclinorium. These belong to the youngest known phacopids and they rank among the victims of the Hangenberg Crisis that took place near the Devonian–Carboniferous boundary. The phacopid fauna formed a trilobite association inhabiting a shallow shelf together with diverse brachiopod but also coral, crinoid, mollusc communities. These Belgian trilobites are compared with Omegops bergicus encountered in the northern France (Avesnois area).

Table des matières

1. Introduction

1The uppermost Famennian of Belgium and northern France (Avesnois area), which corresponds to the Strunian regional substage in this area (Conil & Lys, 1980; Streel et al., 2006), is marked by the significant reappearance of trilobites. Indeed, the absence of trilobites extends from the end of the Frasnian–Famennian biotic crisis to the base of the Strunian. So far, only a single pygidium of an unidentified phacopid genus, which was collected by M. Mourlon in 1883, has been reported from the upper Famennian of southern Belgium by Van Viersen & Koppka (2021).

2In northern France (Avesnois area) (Fig. 1), the latest Famennian phacopids were first reported by Hébert (1855) and Gosselet (1857, 1860, 1871, 1880) as Phacops latifrons (Bronn, 1825), but it was not until several decades later that they were illustrated by Dehée (1929) as Phacops bergicus Drevermann, 1902. From the historical viewpoint, they were first mentioned in southern Belgium, to our knowledge, as Phacops granulosus by Mourlon (1882, 1883a, b; in Dupont & Mourlon, 1883), who used them for characterising the Calcaire de Comblain-au-Pont (Comblain-au-Pont Formation; see Mottequin et al., 2024). Although Gosselet (1888) noted that P. granulosus may be conspecific with P. granulatus (Münster, 1840) (see Brauckmann et al., 1993), he kept the name previously proposed by Mourlon (1882, 1883a, b) pending a formal description of this taxon, which was never published; therefore, rightly explained by Richter & Richter (1933), P. granulosus Mourlon must be considered as a nomen nudum. Phacopid trilobites were of great importance to the pioneers of stratigraphy as they were mentioned in the four first editions of the Légende de la Carte géologique de la Belgique as typical macrofossil of the Famennian assise de Comblain-au-Pont (Fa2d): P. granulosus (Conseil de Direction de la Carte, 1892) and P. granulatus (Conseil de Direction de la Carte, 1896, 1900, 1909). A further step was taken by Richter & Richter (1933), who provided the first description of the Strunian trilobites of Belgium and erected the new subspecies Phacops (Phacops) accipitrinus maretiolensis based on material from Maredsous (Fig. 1). The latter was later ascribed by Struve (1976) to his new subgenus Phacops (Omegops).

3In Belgium, as the rocks yielding the phacopid trilobites were alternatively placed at the top of the Devonian or in the basal Carboniferous, their presence has frequently attracted the attention of geologists, and this interest continues to this day (e.g. Maillieux, 1933; Mortelmans & Bourguignon, 1954; Demanet, 1958; Conil et al., 1967, 1977, 1986; Austin et al., 1970; Dreesen et al., 1976; Denayer et al., 2019, 2021); indeed, these are the youngest known phacopids and they rank among the victims of the Hangenberg Crisis that took place near the Devonian–Carboniferous boundary (DCB) (e.g. Bault, 2023).

4The aim of this paper is to document the last phacopid trilobites from the Upper Devonian (uppermost Famennian, Strunian) from the strata of the Belgian part of the Dinant Synclinorium equivalent of the Hangenberg Sandstone.

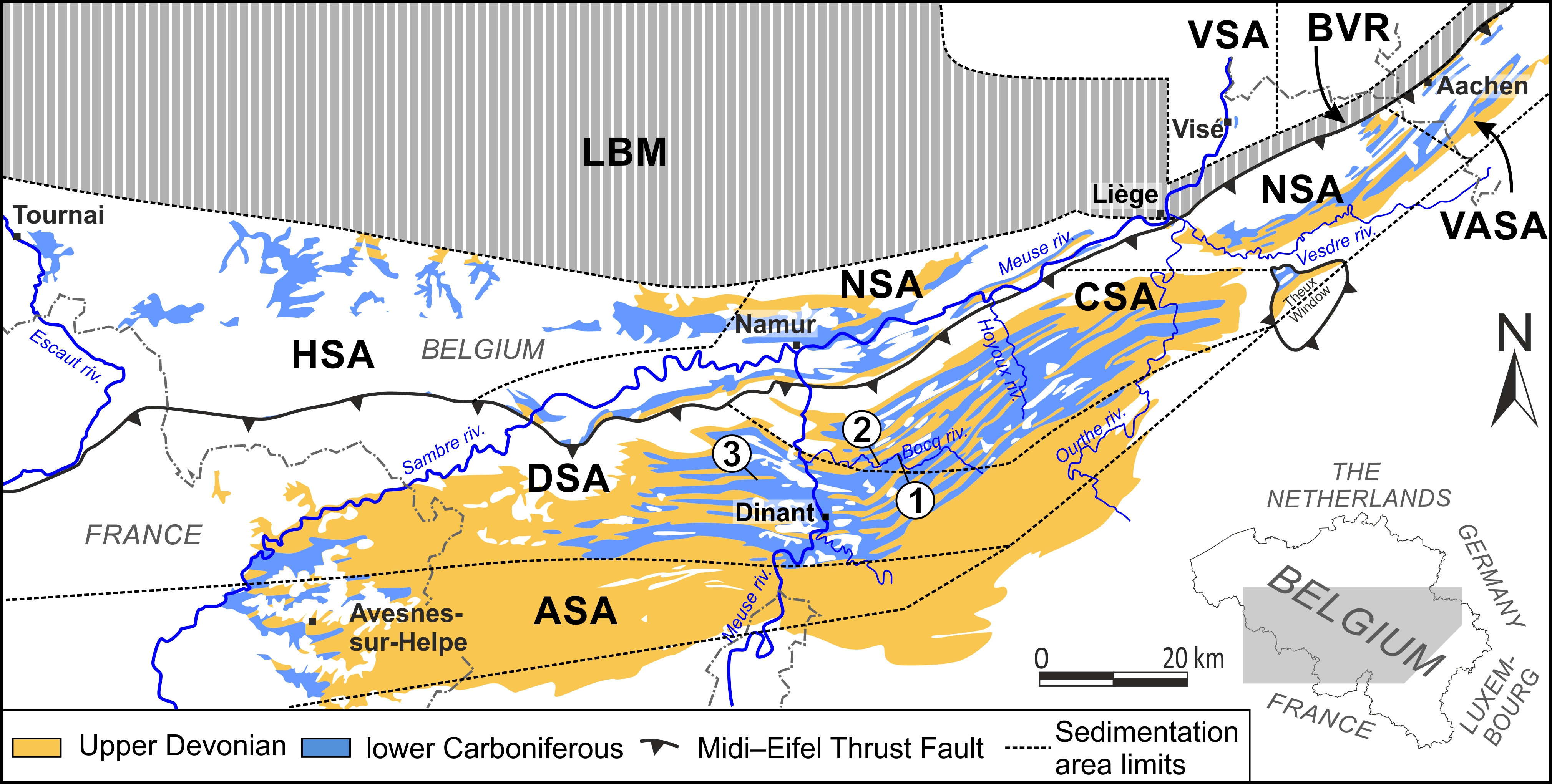

Figure 1. Sedimentation areas in the Namur–Dinant Basin (modified from Poty, 2016) and location map of the sections cited in the text (1, Spontin; 2, Chansin; 3, Maredsous). Abbreviations: ASA, South Avesnois sedimentation area; BVR, Booze–Le-Val-Dieu ridge; CSA, Condroz sedimentation area; DSA, Dinant sedimentation area; HSA, Hainaut sedimentation area; LBM, London–Brabant Massif; NSA, Namur sedimentation area; VASA, Vesdre–Aachen sedimentation area; VSA, Visé–Maastricht sedimentation area.

2. Geological setting

5The Namur–Dinant Basin formed a vast, shallow-water shelf along the southern margin of the Laurussia continent during the Devonian and Carboniferous (e.g. Hance et al., 2001; Mottequin & Denayer, 2024). Nowadays, the Namur–Dinant Basin is preserved in several tectonic structures, mostly cropping out in southern Belgium, but also in the Avesnois area of northern France and Aachen area in western Germany (Fig. 1). The Upper Devonian–lower Carboniferous succession of the Namur–Dinant Basin is well exposed in the Dinant Synclinorium and Vesdre area (Fig. 1). The Famennian (Upper Devonian) is particularly well developed in the Dinant Synclinorium where it comprises a 600 m thick sequence, which is dominated by siliciclastic sediments with some carbonate levels in its middle and uppermost parts (Thorez et al., 2006; Mottequin et al., 2024). The uppermost Famennian (Strunian regional substage) is characterised by a mixed carbonate–siliciclastic sedimentation, which strongly contrasts with the rest of the Famennian succession that is strongly dominated by siliciclastic deposits (Poty, 2016). The uppermost Famennian facies indicate an inner- to median-shelf environment close to the base of the fair-weather wave zone that was influenced by detrital and marine inputs, with frequent storm deposits (Paproth et al., 1986; Thorez & Dreesen, 1986; Van Steenwinkel, 1990).

6The material studied here was collected in two sections (Chansin and Spontin, see below) at the top of the Strunian succession, more precisely in the topmost part of the Comblain-au-Pont Formation and in the lowest part of the Hastière Formation. Both units were described in detail by Denayer et al. (2019, 2021). At the end of the Devonian, the two sections were situated on the southern margin of the Condroz sedimentation area (Fig. 1) sensu Hance et al. (2001) and Poty (2016). In the Dinant and Condroz sedimentation areas, the Comblain-au-Pont Formation, which consists of an alternation of bioclastic limestone and shale beds, yielded a diverse rugose coral fauna (Poty, 1999; Poty et al., 2006; Denayer et al., 2019, 2021) and numerous brachiopods (Legrand-Blain, 1995; Mottequin & Brice, 2016; Denayer et al., 2021). Tabulate corals (Tourneur et al., 1989) and bryozoans (Tolokonnikova et al., 2015) are not uncommon, but deserve to be investigated further as is the case of the molluscs and vertebrate microremains (Denayer et al., 2021). The Hastière Formation is mostly Tournaisian (Hastarian) in age, but its basal bed yields faunas (e.g. campophyllid rugose corals, phacopid trilobites) that indicate a Strunian age (Poty, 2016; Denayer et al., 2021).

3. Material and methods

7Both sampled sections are situated along the touristy Bocq railway, to the east of the Meuse River valley (for more information, see Denayer et al., 2019, 2021) (Fig. 1). The specimens were collected in beds rich in macrofauna and in calcareous intraclasts.

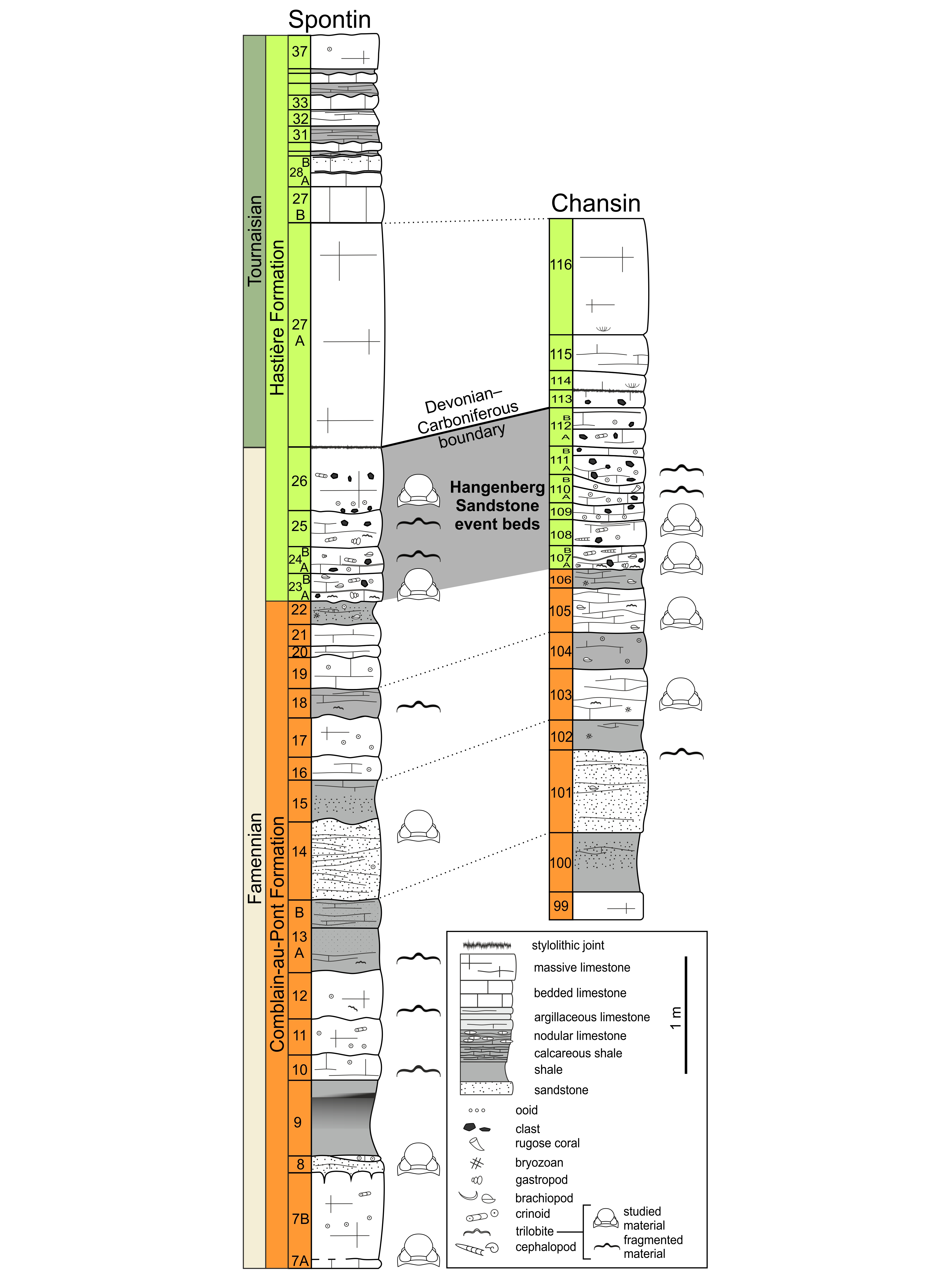

8Chansin. The material was collected within the topmost part of the Comblain-au-Pont Formation (beds 103 and 105) and in the basal part of the overlying Hastière Formation (beds 107 and 108) (Fig. 2).

9Spontin. The phacopids are from the Comblain-au-Pont (beds 7, 8, and 14) and Hastière (bed 23, and 26) formations (Fig. 2).

10All the specimens studied herein are deposited at the Evolution & Diversity Dynamics Lab of the Liège University (Belgium), prefixed PA.ULg.

11The illustrated specimens were lightly coated with ammonium chloride before being photographed using a Nikon digital camera. The morphological terminology follows Whittington & Kelly (1997). The synonymy lists are not intended to be exhaustive and focus essentially on records with illustrations.

Figure 2. Lithological columns of the Spontin and Chansin sections showing the Devonian–Carboniferous transition in neritic facies (modified from Denayer et al., 2019, 2021).

4. Systematic palaeontology

12Order Phacopida Salter, 1864

13Superfamily Phacopoidea Hawle & Corda, 1847

14Family Phacopidae Hawle & Corda, 1847

15Subfamily Phacopinae Hawle & Corda, 1847

16Genus Omegops Struve, 1976

17Type species. Calymene accipitrina Phillips, 1841; from the Upper Devonian Pilton Beds, England.

18Species assigned. Omegops accipitrinus (Phillips, 1841), Famennian (do VI), Belgium, England, Germany, Morocco (see Richter & Richter, 1933); O. cf. accipitrinus (Phillips, 1841), Famennian, Armenia (see Crônier et al., 2021); O. bergicus (Drevermann, 1902), Famennian (do VI), Germany, northern France see Dehée, 1929); O. cornelius (Richter & Richter, 1933), Famennian (do VI), Germany, Central Iran (see Mistiaen et al., 2000); O. cf. cornelius (Richter & Richter, 1933), late Famennian, Eastern Iran (see Feist et al., 2003); O.? cornelius (Richter & Richter, 1933), late Famennian (Strunian), Afghanistan (see Ghobadi Pour et al., 2018 for discussion on the species affiliation); O. insolatus (Struve, 1976), Famennian (do VI), Morocco; O. maretiolensis (Richter & Richter, 1933), Famennian (do VI), Belgium; O. mobilis (Xiang, 1981), late Famennian, NW China (Xinjiang); O. multisegmentatus (Weber, 1937), Famennian (? do VI), Kazakhstan; O. paiensis Farsan, 1998, late Famennian (Strunian), Afghanistan; O. tilabadensis Ghobadi Pour et al., 2018, late Famennian, Northern Iran; O. sp. M (see Struve, 1976, p. 435–436 for this assignation of Moravian representatives described by Chlupáč (1966) as O. accipitrinus), Famennian (do VI), Moravia; O. sp. T (see Struve, 1976, p. 438–439), Famennian (do VI), Morocco; O. sp. (see Yuan & Xiang, 1998), Famennian (do VI), South China (Guangxi).

19Remarks. The main characters of Omegops were presented by Struve (1976), i.e., a reduced preoccipital ring as a narrow flat band, 15–16 dorso-ventral files with a maximum of four to five lenses, a distinct postocular pad, a marginulate lateral border, and coarse tubercles on glabella. But similar genera have meanwhile been erected, and species have been added to Omegops and the main Omegops characters of Struve may now refer to a range of Devonian phacopid genera. Especially the “reduced” preoccipital ring could equally be posited as to represent a broader trend among Late Devonian phacopids (i.e., the blind Famennian Dianops Richter & Richter, 1923). This reduced preoccipital ring is also consistent with the representatives of Boekops (Chlupáč, 1972) from the Lower Devonian as underlined by Chlupáč (1977, p. 76). The large-eyed mid-Frasnian Magreanops van Viersen & Vanherle, 2018, which has a small and flat preoccipital ring marked merely by a few crowded tubercles (van Viersen & Vanherle, 2018, fig.10N), differs in having a less significant sagittal reduction of L1 than in species of Omegops (Fig. 3c, g).

20The assignment to Omegops of two newly described species from western Junggar, Xinjiang, northwest China remains questionable. Omegops honggulelengensis Zong, 2023a, from the middle–upper Famennian, was previously assigned to Omegops cornelius and O. mobilis from the upper Famennian; and O. xiangi Zong, 2023a, from the middle Famennian, was previously assigned by Crônier in Crônier & Waters (2023) to their new genus and species Clarksonops junggariensis. Subsequently, Zong (2023b) reclassified these two species, i.e., Omegops honggulelengensis and O. xiangi respectively to O. mobilis (Xiang, 1981) n. comb. and O. junggariensis (Crônier in Crônier & Waters, 2023) n. comb. to respect the Art. 23 of the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature, 1999). In the diagnosis of Omegops (see Struve, 1976), it is clearly stated that the preoccipital ring is erased and depressed, or barely detectable in oblique light. Neither junggariensis nor xiangi meet this criterion and are therefore not Omegops. Furthermore, Omegops is until recently confined to the uppermost Famennian (Crônier & François, 2014). It therefore seems to us that the affiliation to the genus Clarksonops is justified for these specimens. Omegops honggulelengensis includes the holotype of O. mobilis; honggulelengensis should be a junior synonym of mobilis. Accepting the junior synonymy of the middle–upper Famennian O. honggulelengensis with the latest Famennian O. mobilis, the exclusively uppermost Famennian age for Omegops is questionable. Without a re-evaluation of this material to validate whether there are any notable differences between the specimens from the middle Famennian and the upper Famennian, it is best to consider all specimens as honggulelengensis specimens (sensu Zong, 2023a).

21In Belgium, the studied material from Chansin (40 sclerites: 24 cephala and 16 pygidia) and Spontin (12 sclerites: 8 cephala and 4 pygidia) is most often incomplete, difficult to prepare and often preserved as internal moulds. Due to the smaller number of well-preserved cephala available, additional material is required, but specimens are assigned to Omegops maretiolensis (Richter & Richter, 1933), a common taxon in Belgium, and to O. accipitrinus (Phillips, 1841) on account of the cephalic shape and sculpture. Omegops accipitrinus and O. maretiolensis are present in the same levels and therefore they are considered as separate species and as not subspecies as previously stated by Richter & Richter (1933).

22Omegops accipitrinus is a Late Devonian index fossil (latest Famennian, Strunian regional substage).

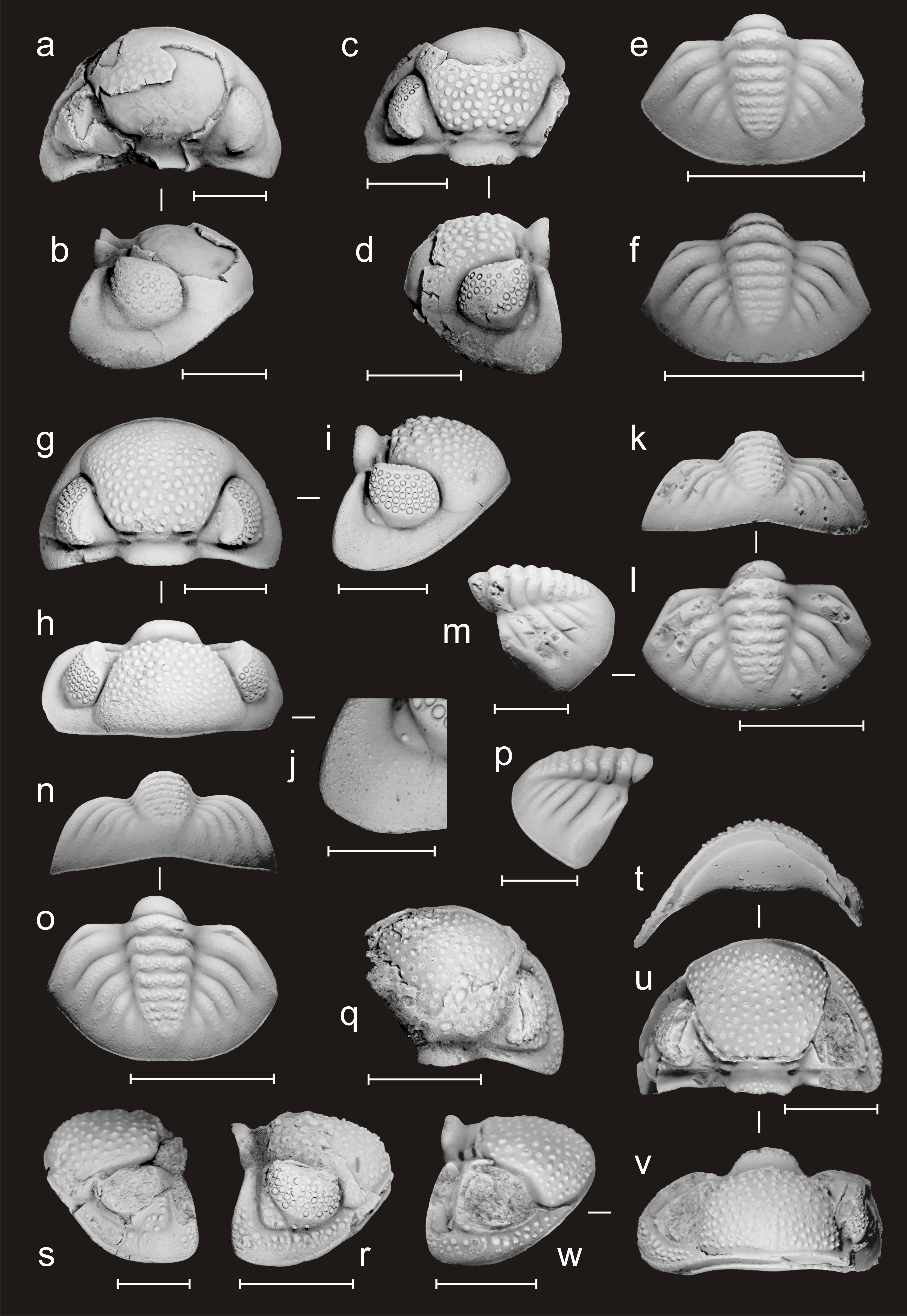

Figure 3. Phacopid trilobites from the Dinant Synclinorium (southern Belgium); all specimens are from the Chansin section (see Figs 1–2). a–p Omegops accipitrinus (Phillips, 1841). a–b Cephalon in dorsal and lateral views (PA.ULg.20240613-1; bed 107). c–d Cephalon in dorsal and lateral views (PA.ULg.20240613-2; bed 107). e Pygidium in dorsal view (PA.ULg.20240613-3; bed 105). f Pygidium in dorsal view (PA.ULg.20240613-4; bed 105). g–j Cephalon in dorsal, frontal and lateral views, and detail of the genal angle (PA.ULg.20240613-5; bed 107). k–m Pygidium in frontal, dorsal and lateral views (PA.ULg.20240613-6; bed 105). n–p Pygidium in frontal, dorsal and lateral views (PA.ULg.20240613-7; bed 107). q–w Omegops maretiolensis (Richter & Richter, 1933). q–r Cephalon in dorsal and lateral views (PA.ULg.20240613-8; bed 107). s Cephalon in lateral view (PA.ULg.20240613-9; bed 107). t–w Cephalon in ventral, dorsal, frontal and lateral views (PA.ULg.20240613-10; bed 108). Scale bars: 5 mm for all, except e, j, m and p: 3 mm.

23Omegops accipitrinus (Phillips, 1841)

24(Figs 3a–p, 4a)

251841 Calymene accipitrina Phillips, p. 128, 152, pl. 56, fig. 249 a–c.

261933 Phacops (Phacops) accipitrinus accipitrinus (Phillips, 1841); Richter & Richter, p. 5–12, pl. 1, figs 1–8 [cum syn.].

27cf. 1937 Phacops (Phacops) cf. accipitrinus (Phillips, 1841); Weber, p. 114, pl. 1, figs 1–5.

281955 Phacops (Phacops) accipitrinus accipitrinus (Phillips, 1841); Goldring, p. 46–47.

29non 1966 Phacops (Phacops) accipitrinus (Phillips, 1841); Chlupáč, p. 103–104, pl. 21, figs 1–5, 12, text-fig. 32.

301969 Phacops (Phacops) accipitrinus (Phillips, 1841); Pillet & de Lapparent, p. 329–330, pl. 39, figs 2–7, 9–18.

311972 Phacops (Phacops) accipitrinus (Phillips, 1841); Alberti, p. 4–21, figs 1–11.

321974 Phacops accipitrinus (Phillips, 1841); Levitskiy, p. 54–56, pl. 1, figs 10–22, text-fig. 3b.

331976 Phacops (Omegops) accipitrinus accipitrinus (Phillips, 1841); Struve, p. 439, pl. 2, fig. 8.

34non 1977 Phacops (subg.?) accipitrinus (Phillips, 1841); Chlupáč, p. 76, pl. XXXII, figs 8–9.

352021 Omegops cf. accipitrinus (Phillips, 1841); Crônier in Crônier et al., p. 4, fig. 2a–d, k.

36Type material. From the Upper Devonian Pilton Beds, England: original number Nr. 7055 (lectotype: cephalon), Museum of Practical Geology (i.e., The British Museum), London.

37Studied material. Eight cephala and eight pygidia from the Comblain-au-Pont Formation to Hastière Formation (uppermost Famennian) of the Chansin and Spontin sections, Belgium.

38Diagnosis. See Richter & Richter (1933).

39Remarks. See remarks for Omegops maretiolensis.

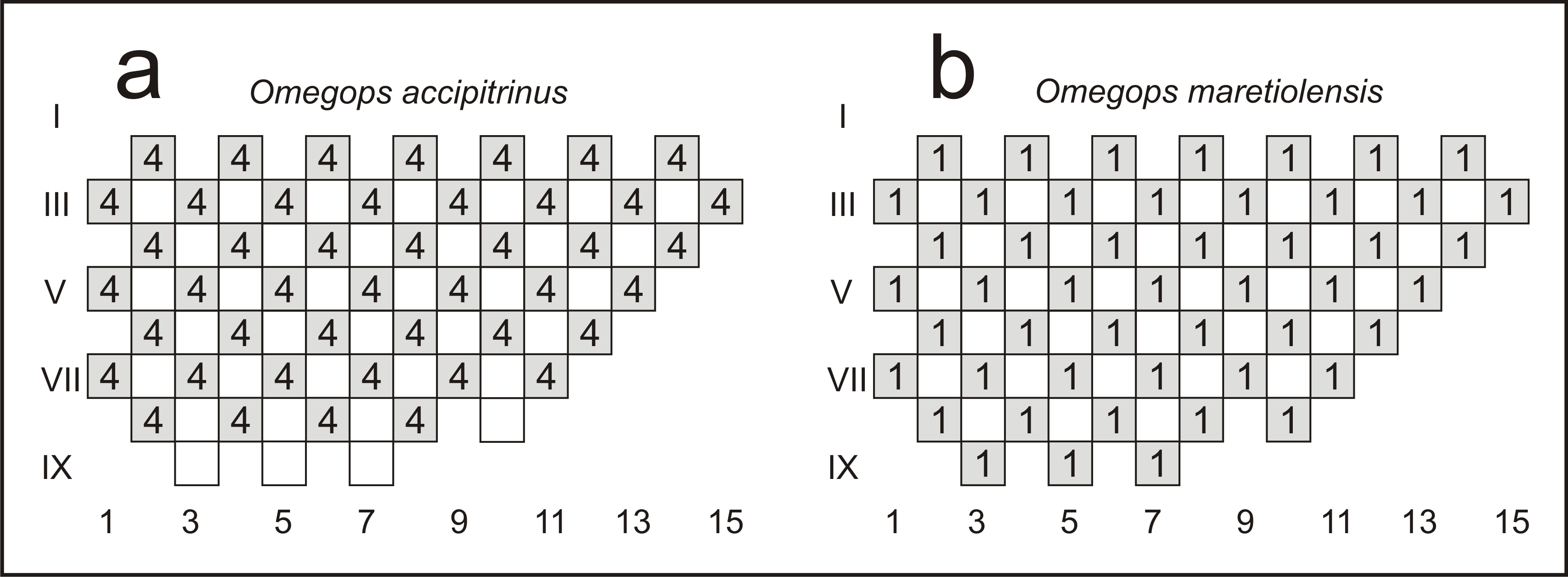

Figure 4. Schematic representation of (a) four visual surfaces in Omegops accipitrinus (Phillips, 1841) and (b) one visual surface in Omegops maretiolensis (Richter & Richter, 1933), following the method of Thomas (1998). Front of visual surface is left; numbers below drawing denominate individual dorso-ventral files, counting from the front (1–15); roman numerals denote successive horizontal rows; numbers in boxes indicate a surface having that lens present in all visual surfaces.

40Omegops maretiolensis (Richter & Richter, 1933)

41(Fig. 3q–w; Fig. 4b)

421933 Phacops (Phacops) accipitrinus maretiolensis Richter & Richter, p. 12–15, pl. 2, figs 9–14 [cum syn.].

43? 1936 Phacops (Ph.) accipitrinus maretiolensis Richter & Richter, 1933; Rome, p. 1–7, pl. 1, figs 1–6, pl. 2, figs 7–12.

441976 Phacops (Omegops) accipitrinus maretiolensis Richter & Richter, 1933; Struve, p. 435, figs 6–7, 16, 19, 28, pl. 1, figs 1–6.

452021 Omegops maretiolensis (Richter & Richter, 1933); Mottequin, p. 37, 59–61, fig. 21A–O.

462024 Omegops maretiolensis; Mottequin et al., p. 213, pl. 4.EE [copy of Mottequin, 2021, fig. 21A].

47Type material. From the Comblain-au-Pont Formation (latest Famennian, ‘Strunian’) of Maredsous (Bioul 525), Belgium: RBINS a7812 (holotype: cephalon), a7813–7817 (paratypes: 3 cephala and 2 pygidia), Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences, Brussels; CGF 020.11.10/12 (paratype: 1 pygidium), Centre Grégoire Fournier, Maredsous (Mottequin, 2021).

48Studied material. Four cephala including two illustrated from the Comblain-au-Pont Formation to Hastière Formation (uppermost Famennian) of the Chansin section, Belgium.

49Diagnosis. See Richter & Richter (1933).

50Remarks. Detailed descriptions of O. accipitrinus and O. maretiolensis were presented by Richter & Richter (1933) and supplemented by Struve (1976). Omegops accipitrinus is characterised by a postocular area that is smooth adaxially and covered with a few tubercles abaxially, up to five lenses in a dorso-ventral file in the eye (with 56‒70 lenses recorded), axial glabellar furrows diverging forwards at about 45‒60°, and two small granules medially on the reduced preoccipital ring. The pygidium of O. accipitrinus according to available data (illustration from Salter, 1864, pl. 1, figs 10, 14 with a reassignment by Richter & Richter, 1933, description from Richter & Richter, 1933), has six pleural ribs but the last two are sometimes indistinct or only recognizable as nodes (see Richter & Richter, 1933, p. 8). Our cephala affiliated to Omegops accipitrinus fit rather well with this description in having 15 dorso-ventral files with a maximum of four lenses (but with only 45 lenses recorded in four visual surfaces), a postocular area that is smooth or with only few tubercles (see Fig. 3b, d). In addition, on the postero-lateral border, small granules and pits are present on the best preserved specimen (Fig. 3i–j). However, our well-preserved pygidia show rather 5 distinct pleural rib pairs and 8 axial rings plus the terminal piece. Omegops maretiolensis is characterised by a postocular pad covered with several tubercles, a row of coarse tubercles on the lateral border, up to five lenses in a dorso-ventral file. The pygidium of O. maretiolensis has seven to nine axial rings and six pleural ribs also, with a relatively long pygidial axis (Struve, 1976), and coarse tubercles (see Mottequin, 2021: fig. 21l–o). Our specimens affiliated to Omegops maretiolensis fit rather well with this description in having 15 dorso-ventral files with a maximum of four lenses (with 49 lenses recorded in the best preserved visual surface). Both taxa co-occur in the same samples and exhibit almost the same distributional pattern of eye-lenses, while they can be discriminated by differences in cephalic sculpture (lateral border and postocular area with numerous coarse tubercles for Omegops maretiolensis and with small granules for O. accipitrinus). While bimodal variability in eye lenses is documented for some phacopids (e.g. Campbell, 1967; Crônier et al., 2015), this pattern has not been reported for any species of Omegops.

51Chlupáč (1966, 1977) described some Moravian specimens he assigned to Phacops (subg.?) accipitrinus encountered in the same levels and exhibiting variability in the density and spacing of tubercles. The subspecies O. accipitrinus maretiolensis was erected on the basis of its lateral border granulation and was not taxonomically justified according to Chlupáč (1966, 1977). However, the absence of a morphological continuum in this character between O. accipitrinus and O. maretiolensis suggests the presence of two distinct species. If additional new material may confirm whether these differences are taxonomically significant, the presence of two morphologically distinct pygidia seems to confirm the presence of two distinct species.

5. Discussion

52The new illustrated specimens of Omegops are partially consistent in pygidial morphology with the taxa originally described from the upper Famennian of Western Europe (Richter & Richter, 1933; Struve, 1976); i.e., in having six pygidial pleural ribs. If Omegops maretiolensis exhibits 6 pleural rib pairs, O. accipitrinus from Belgium seems to show only 5 distinct pleural rib pairs. Based on small but consistent differences in the number of pleural ribs, Ghobadi Pour et al. (2018) suggested the existence of two geographically isolated Omegops lineages which diverged in pre-Strunian time, i.e. taxa with four to five pleural ribs from the Middle East and Northwest China (Junggar) and taxa from Western Europe and North Africa with six or more pygidial pleural ribs. The Belgian Omegops accipitrinus seems to contradict this trend.

53Crônier & François (2014) commented on a bathymetrical gradient in the distribution of Famennian phacopid taxa with Omegops restricted to shallow-water deposits influenced by current activity (as previously reported by Chlupáč, 1977), along both the palaeogeographical South Laurussia and North Peri-Gondwana margins. The Omegops association is encountered in shallow water clastic limestones probable of lower shoreface to upper offshore origin in the upper Famennian. This pattern established by Crônier & François (2014) is consistent in the Dinant synclinorium where O. accipitrinus and O. maretiolensis are significant components of the benthic fauna with abundant brachiopods (e.g. spiriferides, rhynchonellides) that inhabited a limestone substrate rich in bioclasts within an offshore shallow shelf setting. Almost all documented Omegops occurrences, except those of the North African part of Gondwana, were confined to the tropics and subtropics. All phacopid genera became extinct at the end-Famennian Hangenberg Crisis. In this regard, the Famennian is notable for its taxonomic turnovers and the decline in phacopid diversity. Biostratigraphically, the Belgian levels yielding phacopids are of very late Famennian age, corresponding to the Hangenberg Sandstone event, just below the entry of the conodont Protognathodus kockeli.

Acknowledgements

54We thank D. J. Holloway (Australia), A. Van Viersen (the Netherlands) and P. Budil (Czech Republic) as reviewers for their comments and suggestions. This work is a contribution to the French project ‘Contrat de Plan Etat-Région ECRIN’, and to the French CNRS UMR 8198 Evo-Eco-Paleo.

Author contribution

55JD and BM collected the fossil material (a few specimens by CC during the IPC5 congress) whereas CC and RF described it. All authors participated to the writing of the paper.

Data availability

56All studied specimens are housed in official repositories guaranteeing their long-term safekeeping and availability to other researchers for future studies.

References

57Alberti, H., 1972. Ontogenie des Trilobiten Phacops accipitrinus. Neues Jahrbuch für Mineralogie, Geologie und Paläontologie, Abhandlungen, 141, 1–36.

58Austin, R., Conil, R., Rhodes, F. & Streel, M., 1970. Conodontes, spores et foraminifères du Tournaisien inférieur dans la vallée du Hoyoux. Annales de la Société géologique de Belgique, 93/2, 305–315.

59Bault, V., 2023. Trilobites showed strong resilience capacity through the Late Devonian events despite an inexorable decline. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 630, 111807. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2023.111807

60Brauckmann, C., Chlupáč, I. & Feist, R., 1993. Trilobites at the Devonian-Carboniferous boundary. Annales de la Société géologique de Belgique, 115/2 (pro 1992), 507–518.

61Bronn, H., 1825. Ueber zwei neue Trilobiten-Arten zum Calymene-Geschlechte gehörig. Taschenbuch für die gesammte Mineralogie, 19/1, Zeitschrift für Mineralogie, Taschenbuch, 1, 317–321.

62Campbell, K.S.W., 1967. Trilobites of the Henryhouse Formation (Silurian) in Oklahoma. Oklahoma Geological Survey Bulletin, 115, 1–68.

63Chlupáč, I., 1966. The Upper Devonian and Lower Carboniferous trilobites of the Moravian Karst. Sborník geologických věd, paleontologie, 7, 1–143.

64Chlupáč, I., 1972. New Silurian and Lower Devonian phacopid trilobites from the Barrandian area (Czechoslovakia). Casopis pro mineralogii a geologii, 17, 395–401.

65Chlupáč, I., 1977. The phacopid trilobites of the Silurian and Devonian of Czechoslovakia. Rozpravy ústředního ústavu geologického, 43, 1–172.

66Conil, R., & Lys, M., 1980. Strunien. In Cavelier, C. & Roger, J. (eds), Les étages français et leurs stratotypes. Mémoires du Bureau de Recherches géologiques et minières, 109, 26–35.

67Conil, R., Pirlet, H., Lys, M., Legrand, R., Streel, M., Bouckaert, J. & Thorez, J., 1967. Échelle biostratigraphique du Dévonien de la Belgique. Professional Paper of the Geological Survey of Belgium, 1967/13, 1–56.

68Conil, R., Groessens, E. & Pirlet, H., 1977. Nouvelle charte stratigraphique du Dinantien type de la Belgique. Annales de la Société géologique du Nord, 96, 363–371.

69Conil, R., Dreesen, R., Lentz, M.A., Lys, M. & Plodowski, G., 1986. The Devono-Carboniferous transition in the Franco-Belgian basin with reference to foraminifera and brachiopods. In Bless, M.J.M. & Streel, M. (eds), Late Devonian events around the Old Red Continent. Annales de la Société géologique de Belgique, 109/1, 19–26.

70Conseil de Direction de la Carte (avec le concours de la Commission géologique), 1892. Légende de la Carte géologique de la Belgique dressée par ordre du gouvernement à l’échelle du 40.000e. Bulletin de la Société belge de Géologie, de Paléontologie et d’Hydrologie, 6, Procès-verbaux, 217–229.

71Conseil de Direction de la Carte, 1896. Légende de la Carte géologique de la Belgique à l’échelle du 40 000e dressée par ordre du gouvernement. Deuxième édition (avril 1896). Bulletin de la Société belge de Géologie, de Paléontologie et d’Hydrologie, 10, Traductions & Reproductions, 39–59.

72Conseil de Direction de la Carte, 1900. Légende de la Carte géologique de la Belgique à l’échelle du 40 000e, dressée par ordre du gouvernement. Édition de mars 1900. Bulletin de la Société belge de Géologie, de Paléontologie et d’Hydrologie, 14, Traductions & Reproductions, 19–43.

73Conseil de Direction de la Carte, 1909. Légende de la Carte géologique de la Belgique à l’échelle du 40 000e, dressée par ordre du gouvernement. Édition d’octobre 1909. Annales des Mines de Belgique, 14/4, 1635–1658.

74Crônier, C. & François, A., 2014. Distribution patterns of Upper Devonian phacopid trilobites: paleobiogeographical and paleoenvironmental significance. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 404, 12–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2014.03.037

75Crônier, C. & Waters, J.A., 2023. Late Devonian (Famennian) phacopid trilobites from western Xinjiang, Northwest China. Palaeobiodiversity and Palaeoenvironments, 103, 327–340. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12549-022-00547-x

76Crônier, C., Budil, P., Fatka, O. & Laibl, L., 2015. Intraspecific bimodal variability in eye lenses of two Devonian trilobites. Paleobiology, 41, 554–569. https://doi.org/10.1017/pab.2015.29

77Crônier, C., Serobyan, V., Grigoryan, A., Witt, C. & Danelian, T., 2021. A preliminary account on Devonian trilobites from Armenia. Proceedings NAS RA, Earth Sciences, 74/2, 3–15.

78Dehée, R., 1929. Description de la faune d’Etrœungt – Faune de passage du Dévonien au Carbonifère. Mémoires de la Société géologique de France, nouvelle série, 5, 1–62.

79Demanet, F., 1958. Contribution à l’étude du Dinantien de la Belgique. Mémoires de l’Institut royal des Sciences naturelles de Belgique, 141, 1–152.

80Denayer, J., Prestianni, C., Mottequin, B. & Poty, E., 2019. Field trip A1: the uppermost Devonian and Lower Carboniferous in the type area of southern Belgium. In Aretz, M., Herbig, H.-G., Hartenfels, S. & Amler, M. (eds), 19th International Congress on the Carboniferous and Permian, Cologne 2019, field guidebooks. Kölner Forum für Geologie und Paläontologie, 24, 5–41.

81Denayer, J., Prestianni, C., Mottequin, B., Hance, L. & Poty, E., 2021. The Devonian–Carboniferous boundary in Belgium and surrounding areas. Palaeobiodiversity and Palaeoenvironments, 101, 313–356. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12549-020-00440-5

82Dreesen, R., Dusar, M. & Groessens, E., 1976. Biostratigraphy of the Yves-Gomezée road section (Uppermost Famennian). Service géologique de Belgique, Professional Papers, 1976/6, 1–20.

83Drevermann, F., 1902. Ueber eine Vertretung der Étroeungt-Stufe auf der rechten Rheinseite. Zeitschrift der Deutschen Geologischen Gesellschaft, 54, 480–524. https://doi.org/10.1127/zdgg/54/1902/480

84Dupont, E. & Mourlon, M., 1883. Compte rendu de la seconde partie de l’excursion du 11 septembre, de Hastière à Waulsor[t], Freyr et Dinant. Bulletin de la Société géologique de France, 3e série, 11, 715–726.

85Farsan, N.M., 1998. Das Etroeungtium (Ober-Devon VI, Strunium) und die letzten Phacopinae (Trilobita) im westlichen Zentral- und West-Afghanistan. Mainzer Naturwissenschaftliches Archiv Beiheft, 21, 17–37.

86Feist, R., Yazdi, M. & Becker, T., 2003. Famennian trilobites from the Shotori Range, E–Iran. Annales de la Société géologique du Nord, 2e série, 10/4, 285–295.

87Ghobadi Pour, M., Popov, L.E., Omrani, M. & Omrani, H., 2018. The latest Devonian (Famennian) phacopid trilobite Omegops from eastern Alborz, Iran. Estonian Journal of Earth Sciences, 67, 192–204. https://doi.org/10.3176/earth.2018.16

88Goldring, R., 1955. The Upper Devonian and Lower Carboniferous trilobites of the Pilton Beds in N. Devon, with an appendix on goniatites of the Pilton Beds. Senckenbergiana lethaea, 36, 27–48.

89Gosselet, J., 1857. Note sur le terrain dévonien de l’Ardenne et du Hainaut. Bulletin de la Société géologique de France, 2e série, 14, 364–374.

90Gosselet, J., 1860. Mémoire sur les terrains primaires de la Belgique, des environs d’Avesnes et du Boulonnais. Imprimerie L. Martinet, Paris, 164 p.

91Gosselet, J., 1871. Esquisse géologique du Nord de la France et des contrées voisines (suite). Bulletin scientifique, historique et littéraire du Département du Nord et des pays voisins (Pas-de-Calais, Somme, Aisne, Ardennes, Belgique), 3, 291–301.

92Gosselet, J., 1880. Esquisse géologique du Nord de la France et des contrées voisines. 1er fascicule : Terrains primaires (texte). Imprimerie Six-Horemans, Lille, 167 p.

93Gosselet, J., 1888. L’Ardenne. Ministère des travaux publics, Mémoires pour servir à l’Explication de la Carte géologique détaillée de la France. Baudry & Cie, Paris, 889 p.

94Hance, L., Poty, E. & Devuyst, F.-X., 2001. Stratigraphie séquentielle du Dinantien type (Belgique) et corrélation avec le Nord de la France (Boulonnais, Avesnois). Bulletin de la Société géologique de France, 172, 411–426. https://doi.org/10.2113/172.4.411

95Hawle, I. & Corda, A.J.C., 1847. Prodrom einer Monographie der böhmischen Trilobiten. J.G. Calve’sche Buchhandlung, Prague, 176 p. Hébert, M., 1855. Quelques renseignements nouveaux sur la constitution géologique de l’Ardenne française. Bulletin de la Société géologique de France, 2e série, 12, 1165–1186.

96International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature, 1999. International Code of Zoological Nomenclature: adopted by the International Union of Biological Sciences (4th ed.). The International Trust for Zoological Nomenclature, London, 124 p.

97Legrand-Blain, M., 1995. Relations entre les domaines d’Europe occidentale, d’Europe méridionale (Montagne Noire) et d’Afrique du Nord à la limite Dévonien-Carbonifère : les données des brachiopodes. Bulletin de la Société belge de Géologie, 103/1-2 (pro 1994), 77–97.

98Levitskiy, E.S., 1974. Razvitie verchnedevonskich predstavitelej roda Phacops Emmrich, 1839 (s.l.). Izvestiya vysshikh uchebnykh zavedeniy, Geologiya i Razvedka, 8, 24–31. [In Russian].

99Maillieux, E., 1933. Terrains, roches et fossiles de la Belgique. Deuxième édition revue et corrigée. Patrimoine du Musée royal d’Histoire naturelle de Belgique, Bruxelles, 217 p.

100Mistiaen, B., Gholamalian, H., Gourvennec, R., Plusquellec, Y., Bigey, F., Brice, D., Feist, M., Feist, R., Ghobadi Pour, M., Kebria-EE, M., Milhau, B., Nicollin, J.-P., Rohart, J.-C., Vachard, D. & Yazdi, M., 2000. Preliminary data on the Upper Devonian (Frasnian, Famennian) and Permian fauna and flora from the Chahriseh area (Esfahan Province, Central Iran). Annales de la Société géologique du Nord, 2e série, 8, 93–102.

101Mortelmans, G. & Bourguignon, P., 1954. Le Dinantien. In Fourmarier, P. (ed.), Prodrome d’une description géologique de la Belgique. Société géologique de Belgique, Liège, 217–310.

102Mottequin, B., 2021. Earth science collections of the Centre Grégoire Fournier (Maredsous) with comments on Middle Devonian–Carboniferous brachiopods and trilobites from southern Belgium. Geologica Belgica, 24/1-2, 33–68. https://doi.org/10.20341/gb.2020.028

103Mottequin, B. & Brice, D., 2016. Upper and uppermost Famennian (Devonian) brachiopods from north-western France (Avesnois) and southern Belgium. In Denayer, J. & Aretz, M. (eds), Devonian and Carboniferous research: homage to Professor Edouard Poty. Geologica Belgica, 19/1-2, 121–134. https://doi.org/10.20341/gb.2016.004

104Mottequin, B. & Denayer, J., 2024. Revised lithostratigraphic scale of the Devonian of Belgium: An introduction and an homage to Pierre Bultynck. In Mottequin, B. & Denayer, J. (eds), Devonian lithostratigraphy of Belgium. Geologica Belgica, 27/3-4, 105–114. https://doi.org/10.20341/gb.2024.008

105Mottequin, B., Denayer, J., Delcambre, B., Marion, J.-M. & Poty, E., 2024. Upper Devonian lithostratigraphy of Belgium. In Mottequin, B. & Denayer, J. (eds), Devonian lithostratigraphy of Belgium. Geologica Belgica, 27/3-4, 193–270. https://doi.org/10.20341/gb.2024.010

106Mourlon, M., 1882. Considérations sur les relations stratigraphiques des psammites du Condroz et des schistes de la Famenne proprement dits, ainsi que sur le classement de ces dépôts dévoniens. Bulletins de l’Académie royale des Sciences, des Lettres et des Beaux-Arts de Belgique, 3e série, 4, 504–521.

107Mourlon, M., 1883a. Sur la question des faciès, à propos du classement stratigraphique des dépôts famenniens de la Belgique et du nord de la France. Bulletin de la Société géologique de France, 3e série, 11, 692–698.

108Mourlon, M., 1883b. Compte rendu de l’excursion du 11 septembre, de Heer à Hastière, dans le terrain famennien (Dévonien supérieur). Bulletin de la Société géologique de France, 3e série, 11, 708–714.

109Münster, G.G., 1840. Die Versteinerungen des Uebergangskalkes mit Clymenien und Orthoceratiten von Oberfranken. Beiträge zur Petrefakten-Kunde, 3, 33–121.

110Paproth, E., Dreesen, R. & Thorez, J., 1986. Famennian paleogeography and event stratigraphy of northwestern Europe. Annales de la Société géologique de Belgique, 109/1, 175–186.

111Phillips, J., 1841. Figures and descriptions of the Palaeozoic fossils of Cornwall, Devon, and West Somerset. Longman, London, 231 p. https://doi.org/10.5962/t.173086

112Pillet, J. & de Lapparent, A.F., 1969. Description de trilobites ordoviciens, siluriens et dévoniens d’Afghanistan. Annales de la Société géologique du Nord, 89, 323–333.

113Poty, E., 1999. Famennian and Tournaisian recoveries of shallow water Rugosa following late Frasnian and late Strunian major crises, southern Belgium and surrounding areas, Hunan (South China) and the Omolon region (NE Siberia). Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 154, 11–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0031-0182(99)00084-x

114Poty, E., 2016. The Dinantian (Mississippian) succession of southern Belgium and surrounding areas: stratigraphy improvement and inferred climate reconstruction. In Denayer, J. & Aretz, M. (eds), Devonian and Carboniferous research: homage to Professor Edouard Poty. Geologica Belgica, 19/1-2, 177–200. https://doi.org/10.20341/gb.2016.014

115Poty, E., Devuyst, F.-X. & Hance, L., 2006. Upper Devonian and Mississippian foraminiferal and rugose coral zonations of Belgium and northern France: a tool for Eurasian correlations. Geological Magazine, 143/6, 829–857. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0016756806002457

116Richter, R. & Richter, E., 1923. Systematik und Stratigraphie der Oberdevon-Trilobiten des Ostthüringischen Schiefergebirges. Senckenbergiana, 5, 59–76.

117Richter, R. & Richter, E., 1933. Die letzten Phacopidae. Bulletin du Musée royal d’Histoire naturelle de Belgique, 9/21, 1–19.

118Rome, R., 1936. Note sur la microstructure de l’appareil tégumentaire de Phacops (Ph.) accipitrinus maretiolensis R. & E. Richter. Bulletin du Musée royal d’Histoire naturelle de Belgique, 12/31, 1–7.

119Salter, J.W., 1864. A monograph of British trilobites. Part 1. Monographs of the Palaeontographical Society, 16/67, 1–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/02693445.1864.12113212

120Streel, M., Brice, D. & Mistiaen, B., 2006. Strunian. In Dejonghe, L. (ed.), Chronostratigraphic units named from Belgium and adjacent areas. Geologica Belgica, 9/1-2, 105–109.

121Struve, W., 1976. Beiträge zur Kenntnis der Phacopina (Trilobita), 9: Phacops (Omegops) n. sg. (Trilobita; Ober-Devon). Senckenbergiana lethaea, 56, 429–451.

122Thomas, A.T.,1998. Variation in the eyes of the Silurian trilobites Eophacops and Acaste and its significance. Palaeontology, 41, 897–911.

123Thorez, J. & Dreesen, R., 1986. A model of a regressive depositional system around the Old Red Continent as exemplified by a field trip in the upper Famennian ‘Psammites du Condroz’ in Belgium. Annales de la Société géologique de Belgique, 109/1, 285–323.

124Thorez, J., Dreesen, R. & Streel, M., 2006. Famennian. In Dejonghe, L. (ed.), Chronostratigraphic units named from Belgium and adjacent areas. Geologica Belgica, 9/1-2, 27–45.

125Tolokonnikova, Z., Ernst, A., Poty, E. & Mottequin, B., 2015. Middle and uppermost Famennian (Upper Devonian) bryozoans from southern Belgium. Bulletin of Geosciences, 90/1, 33–49. https://doi.org/10.3140/bull.geosci.1527

126Tourneur, F., Conil, R. & Poty, E., 1989. Données préliminaires sur les tabulés et les chaetetidés du Dinantien de la Belgique. Bulletin de la Société belge de Géologie, 98/3-4, 401–442.

127Van Steenwinkel, M., 1990. Sequence stratigraphy from ‘spot’ outcrops – example from a carbonate-dominated setting: Devonian–Carboniferous transition, Dinant synclinorium (Belgium). Sedimentary Geology, 69, 259–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/0037-0738(90)90053-V

128Van Viersen, A.P. & Koppka, J., 2021. Type and other species of Phacopidae (Trilobita) from the Devonian of the Ardenno-Rhenish Mountains. Mainzer geowissenschaftliche Mitteilungen, 49, 25–66.

129Van Viersen, A.P. & Vanherle, W., 2018. The rise and fall of Late Devonian (Frasnian) trilobites from Belgium: taxonomy, biostratigraphy and events. Geologica Belgica, 21/1-2, 73–94. https://doi.org/10.20341/gb.2018.005

130Weber, V.N., 1937. Trilobity kamennougol'nykh i permskikh otlozhenii SSSR. I. Kamennougol'nye trilobity. Monografii po paleontologii SSSR, 71, 1–160. [In Russian].

131Whittington, H.B. & Kelly, S.R.A., 1997. Morphological terms applied to Trilobita. In Kaesler, R.L. (ed.), Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology, Pt. O, Arthropoda 1, Trilobita 1 (revised). Geological Society of America and University of Kansas Press, Boulder (CO) and Lawrence (KS), 313–329.

132Xiang, L.-W., 1981. Some Late Devonian trilobites of China. In Teichert, C., Liu, L. & Chen P.-j. (eds), Paleontology in China, 1979. Geological Society of America, Special Papers, 187, 183–187. https://doi.org/10.1130/spe187-p183

133Yuan, J.L. & Xiang, L.W., 1998, Trilobite fauna at the Devonian–Carboniferous boundary in South China (S. Guizhou and N. Guangxi). National Museum of Natural Science, Special Publication, 8, 1–281.

134Zong, R-W., 2023a. Variation in eye lenses of two new Late Devonian phacopid trilobites from western Junggar, NW China. Journal of Paleontology, 97/4, 891–905. https://doi.org/10.1017/jpa.2023.31

135Zong, R-W., 2023b. Variation in eye lenses of two new Late Devonian phacopid trilobites from western Junggar, NW China - Corrigendum. Journal of Paleontology, 97/4, 958. https://doi.org/10.1017/jpa.2023.42

136Manuscript received 20.06.2024, accepted in revised form 10.01.2025, available online 25.04.2025.