- Startpagina tijdschrift

- Volume 28 (2025)

- number 3-4

- Predator-prey dynamics in a latest Cretaceous marine ecosystem: mosasaur and shark attacks on the echinoid Hemipneustes striatoradiatus from the Maastrichtian type area (the Netherlands, Belgium)

Weergave(s): 960 (14 ULiège)

Download(s): 284 (2 ULiège)

Predator-prey dynamics in a latest Cretaceous marine ecosystem: mosasaur and shark attacks on the echinoid Hemipneustes striatoradiatus from the Maastrichtian type area (the Netherlands, Belgium)

Abstract

Three tests of the holasteroid echinoid Hemipneustes striatoradiatus from the Belgian-Dutch type area of the Maastrichtian Stage preserving evidence of vertebrate-invertebrate interactions are documented and analysed. One specimen exhibits adoral pentagonal puncture marks and a large aboral scar from a mosasaur attack, with Mosasaurus hoffmannii as the presumed predator. A second test preserves evidence of two separate attacks, the first by a mosasaur, presumably Plioplatecarpus marshi, leaving both a pentagonal adoral scar and a large aboral one, and the second by a shark, leaving non-penetrating small, deep triangular pits with tapering tails. A similar pitting is seen on the third test, arranged in clusters and here interpreted as a shark bite from above followed by a second bite subsequent to a 90° rotation of the echinoid. These finds provide the first unambiguous evidence of mosasaur predation on Hemipneustes and add to the sparse record of shark-echinoid interactions, suggesting that predation on large holasteroids by vertebrates was more frequent than previously recognised. All three tests also exhibit syn vivo and post-mortem invertebrate interactions, including also an undescribed serpulid.

Inhoudstafel

1. Introduction

1Direct evidence of vertebrate-invertebrate interactions in deep time is rare, and sources available to infer such relationships are limited. The diet of large vertebrates offers one potential line of evidence, as reconstructed from scarce direct proof such as stomach (gastrolites) and intestinal (cololites) contents in (semi-) articulated specimens, or more commonly from indirect evidence, such as vomit (regurgtitalites), faeces (coprolites) and leftover falls (pabulites) (e.g. Hoffmann et al., 2019; Klug et al., 2021; Barten et al., 2024a; Fischer et al., 2025; Hunt & Lucas, 2025; Serafini et al., 2025). Additional insights may be obtained from tooth morphology and microwear (e.g. Holwerda et al., 2023), as well as chemical traces, such as stable isotope analyses of bones and tooth enamel or microbiome residues in digestive products (bromalites) (e.g. Giltaij et al., 2021; Assemat et al., 2025; Polcyn et al., 2025). Pathologies in the hard parts of invertebrates, such as shell or test malformations in ammonoid cephalopods or echinoids, as well as instances of breakage or missing fragments, offer another potential source of information, provided such abnormalities can be interpreted unambiguously (e.g. Dollo, 1913; Kauffman & Kesling, 1960; Lingham-Soliar & Nolf, 1990; Kauffman, 2004; Keupp, 2012; Neumann & Hampe, 2018; Jain et al., 2025; Tajika et al., 2025).

2Ranking amongst the commonest larger invertebrates of the Belgian-Dutch Maastrichtian type area is the holasteroid echinoid Hemipneustes striatoradiatus (Leske, 1778), attaining test sizes in excess of 10 cm (Jagt, 2000). These notable fossils are highly sought after by collectors, having been traded globally since the late 19th century (e.g., by the ‘Comptoir Ubaghs’; Ubaghs, 1885; Jagt, 2021; Jagt et al., 2024a). Test fragments of Hemipneustes are typical bioclasts in the Maastricht Formation, even rock building at certain levels (Felder, 1975; Felder & Bosch, 2000).

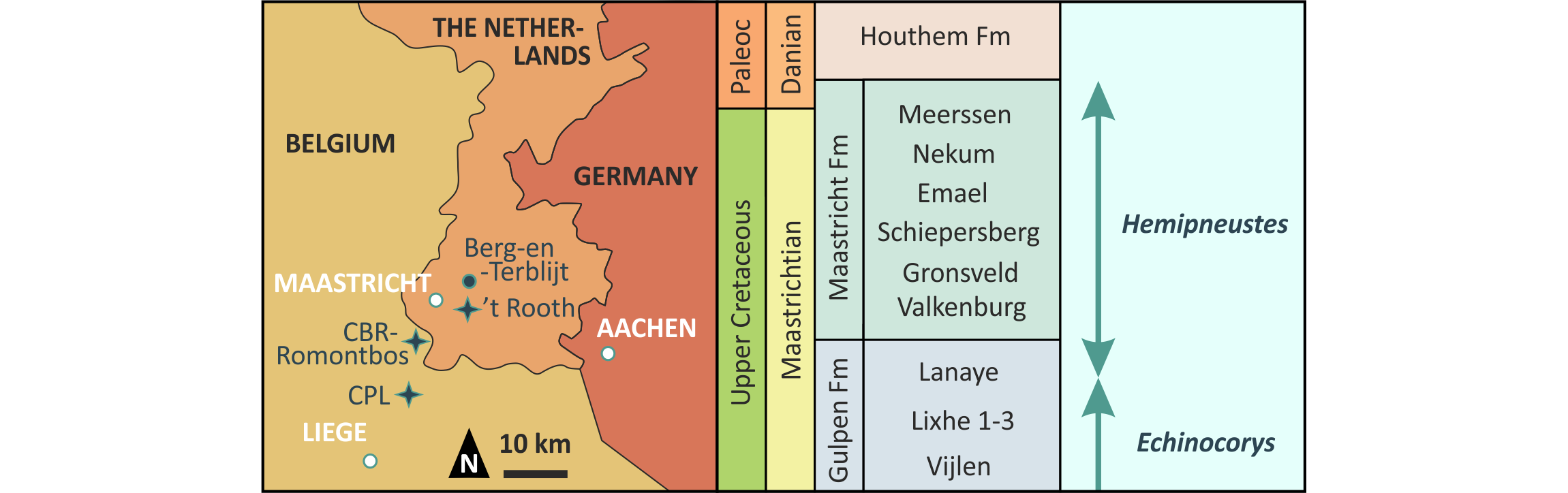

3Over recent decades, several types of pathologies and traces have been identified in Hemipneustes and Echinocorys, another dominant holasteroid of the Maastrichtian type area echinoid fauna that preceded Hemipneustes (Defour et al., 1994; Donovan & Jagt, 2002, 2004, 2005, 2009, 2013a, b, 2014, 2018, 2020a, b; Donovan et al., 2008, 2010, 2014, 2015, 2018; Jagt et al., 2018). Remarkably, this ‘turnover’ from Echinocorys to Hemipneustes occurred during a very limited interval within the late Maastrichtian (between flint beds 10 and 12 of the Lanaye Member, Gulpen Formation; less than one precession cycle, ~21 kyr in absolute time; about 1.6 myr prior to the Cretaceous/Paleogene (K/Pg) boundary; Fig. 1). It marks a transition to shallower water conditions and an influx of Tethyan fauna (Vellekoop et al., 2022; Jagt et al., 2024b; Huygh et al., 2025).

4Yet only a limited number of these echinoid tests appear to document interactions with vertebrates, in the form of predatory (biting or gnawing) traces (praedichnia; Ekdale, 1985). Clear evidence of mosasaur predation on these large holasteroids in the type Maastrichtian is lacking (Jagt et al., 2018), and even on a regional or global scale, only for a single test of Echinocorys from the German Upper Cretaceous have bite marks attributed to mosasaurs been documented (Neumann & Hampe, 2018). There are some examples of fish predation on Echinocorys from the Maastrichtian type area (e.g. Dortangs, 1998, pl. 28, fig. 8; Jagt et al., 2018, fig. 10), with similar examples from the German Campanian to Maastrichtian (e.g. Gripp, 1929; Thies, 1985; Frerichs,1987; Girod et al., 2023), and one test of type-Maastrichtian Hemipneustes bears evidence of a shark attack (Donovan & Jagt, 2020b; Barten et al., 2024b).

5Here, I document three tests of Hemipneustes striatoradiatus that preserve evidence of such vertebrate encounters and discuss the potential predators and their modus operandi. Additionally, the tests preserve evidence of interactions with invertebrates, including both syn vivo colonisation as well as post-mortem encrustation.

Figure 1. Geography and stratigraphy of the Maastrichtian type area, showing localities discussed in the text. The ranges of the two large holasteroid echinoid genera from the Maastrichtian type area are plotted onto the chrono- (Series and Stage) and lithostratigraphy (Formation and Member) (after Felder & Bosch, 2000; Jagt & Jagt-Yazykova, 2012; Jagt et al., 2024a; and van Lochem et al., 2025). Abbreviations: Fm, Formation; Paleoc, Paleocene.

2. Material and methods

6Three specimens of Hemipneustes striatoradiatus, housed in the palaeontological collections of the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences (RBINS; IRSNB in specimen numbers) (Figs 2–6), are as follows:

-

IRSNB 11513, Maastricht Formation, CBR-Romontbos quarry, Eben-Emael, Belgium (ex Robert Pieters Collection, Geel, Belgium);

-

IRSNB 11514, Nekum Member, Maastricht Formation, ’t Rooth quarry, Bemelen, the Netherlands (ex Jacques Severijns Collection, Maastricht, the Netherlands);

-

IRSNB 11515, Maastricht Formation, unspecified quarry, Berg en Terblijt, the Netherlands (ex Guillaume Robert Collection, 1937–2011).

7Specimens were freed from the matrix by their respective collectors and additional cleansing was achieved by the author through short and careful sand blasting using natrium bicarbonate powder as abrasive agent.

8The reader is referred to Felder & Bosch (2000), Jagt & Jagt-Yazykova (2012), Jagt et al. (2024a) and van Lochem et al. (2025), and references therein, for details on localities and regional stratigraphy.

9Specimens were photographed using a DSLR Canon Eos D600 camera in day light.

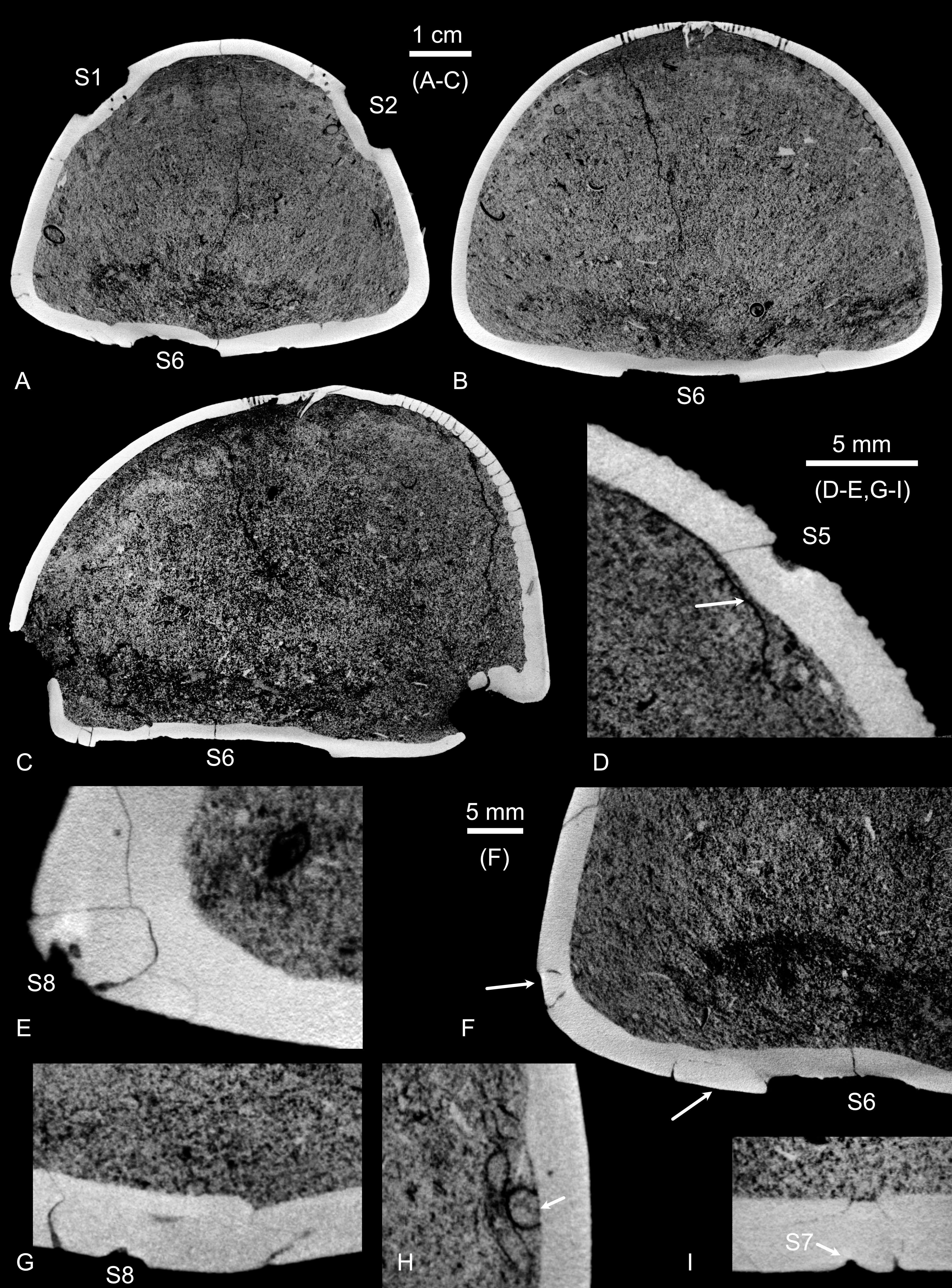

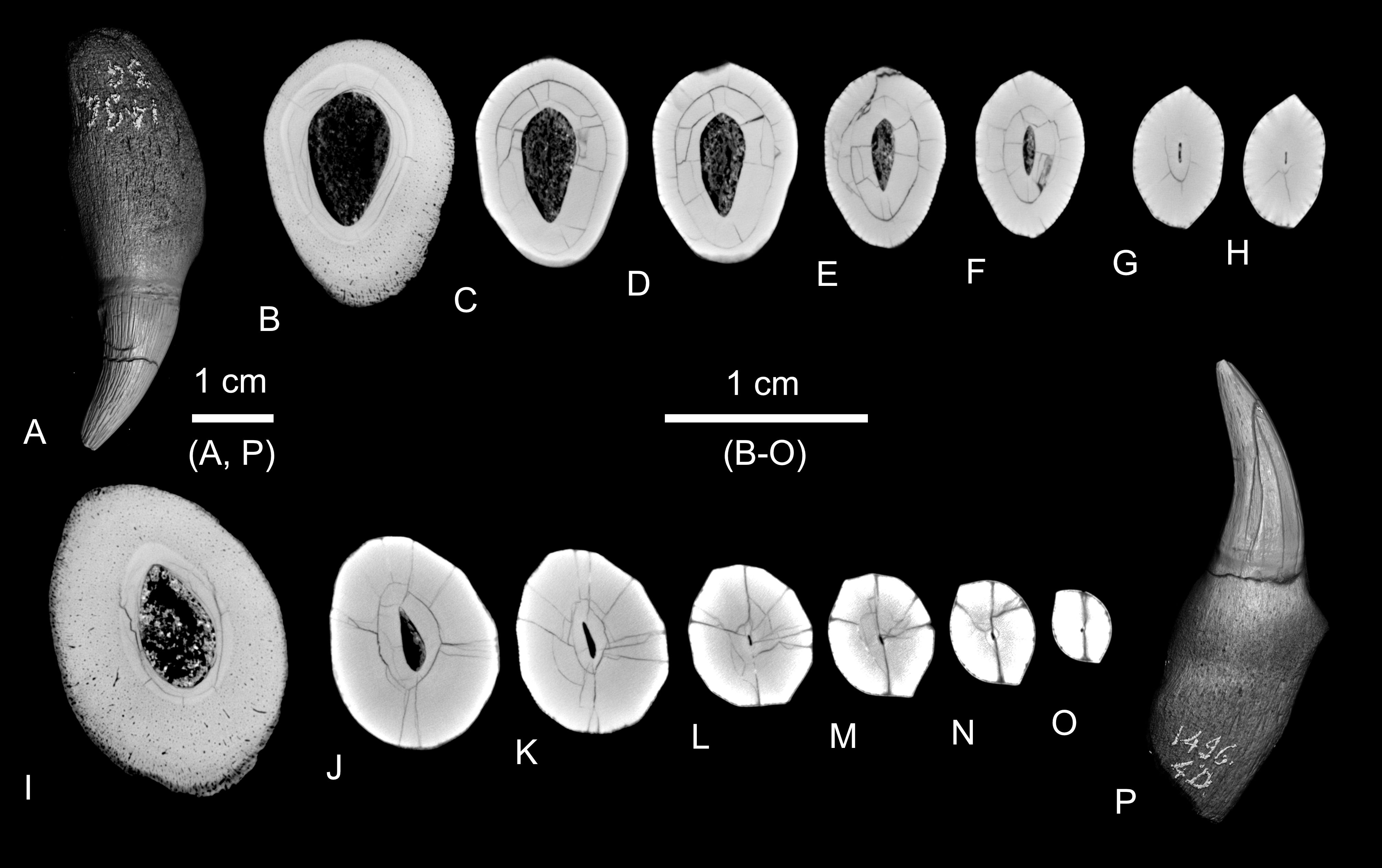

10Specimen IRSNB 11513 and two teeth of Plioplatecarpus marshi Dollo, 1882 (IRSNB R0039) were also digitised using the RBINS micro-CT RX EasyTom 150 of RX Solutions (Chavanod, France), at 48.87 and 23.35 µm voxel size, respectively. Extraction into a 16-bit TIFF stack was performed with X-Act, visualisation, measurements (e.g., test thickness) and segmentation executed with Dragonfly ORS (e.g. Figs 2, 3 and 7). Extracted meshes were also studied in GOM Inspect, some screenshots are illustrated in Figure 5.

11Additional metadata on RBINS specimens discussed in the text can be found on the RBINS Virtual Collections platform. The original micro-CT imaging data of IRSNB 11513 and the two teeth of IRSNB R0039 may be obtained upon request from the RBINS palaeontology collection manager.

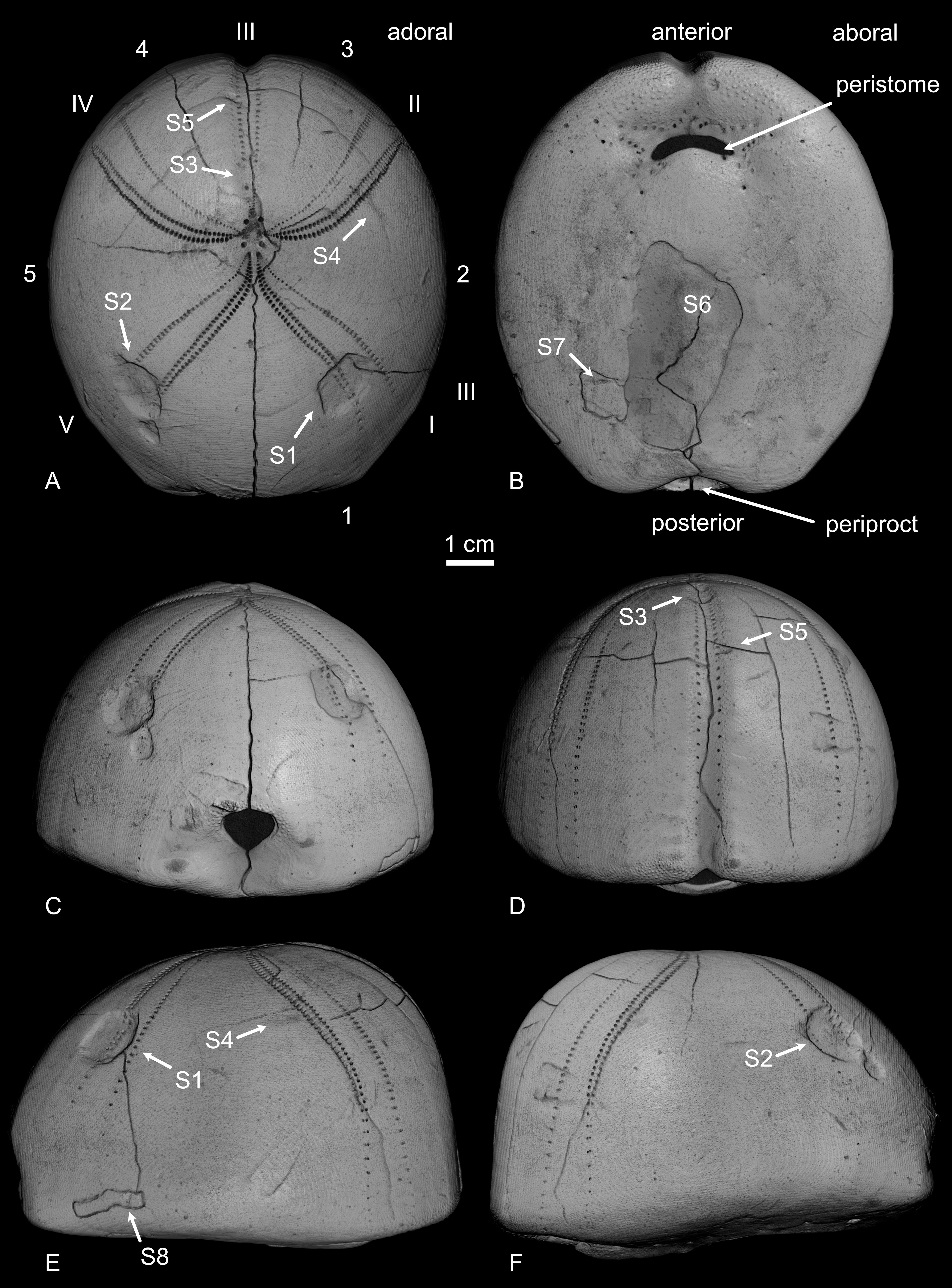

12Morphological terminology of the echinoid test follows Melville & Durham (1966) and the Lovénian system is used for the numbering of ambulacra and interambulacra (summarised in Fig. 2).

13NHMM refers to the Natuurhistorisch Museum Maastricht, Maastricht, the Netherlands.

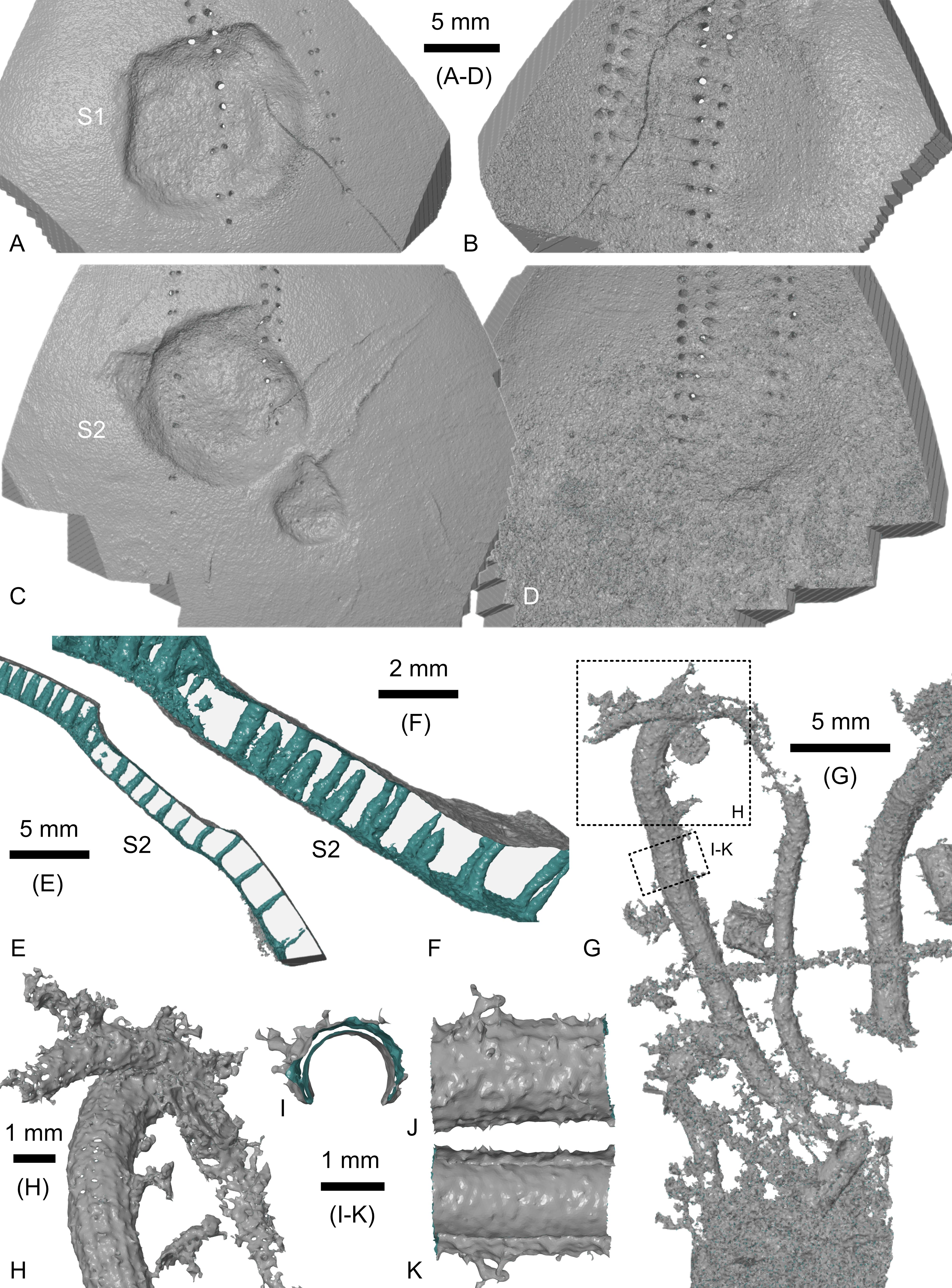

Figure 2. Hemipneustes striatoradiatus (Leske, 1778), specimen IRSNB 11513, Maastricht Formation, CBR-Romontbos quarry, Eben-Emael, Belgium. A–F. 3D renders from micro-CT imaging, illustrating various views of the test and showing general terminology (A), including ambulacra (I–V) and interambulacra (1–5) in the Lovénian system. Positions of scars S1–S8, as discussed in the text, are shown as well.

3. Description

3.1. Specimen IRSNB 11513 (Figs 2–5)

14Large-sized test, measuring 91.5 mm in length, 80.6 mm in width and 61.8 mm in height, exhibiting well-preserved microtuberculation.

15Five scars are present on the aboral side: two large and deep, near-symmetrically implanted pentagonal holes (S1, S2), two shallower elongated ones of moderate size (S3, S4) and one small, yet rather deep, one (S5). Additionally, one larger, deep scar is found on the adoral side (S6).

16The first pentagonal scar (S1) is located above test mid-height in ambulacrum I, measuring 12.5 mm along the ambulacrum and 13.7 mm perpendicular to it. It has two straight edges, each measuring 9.2 mm, one more or less straight edge measuring 6.5 mm, and one more rounded edge with the endpoints 11.5 mm apart. Microtuberculation covers the entire depression, including its walls. Within the scar, the ambulacral pores appear interrupted externally, with the inner row being more disrupted than the outer row. However, micro-CT imaging has revealed that pores are still present internally, although many are sealed on their external side (Fig. 5A, B). Test thickness is reduced within the scar, with additional stereom deposited around its internal side, smoothing over and obscuring the sharpness of the original puncture (Fig. 5A, B).

Figure 3. Hemipneustes striatoradiatus (Leske, 1778), specimen IRSNB 11513. A–I. Virtual sections of test and scars, illustrating puncture morphology, healing features and internal structure. The 12-keeled serpulid with an aragonitic tube is attached to the inner test wall (H, arrow).

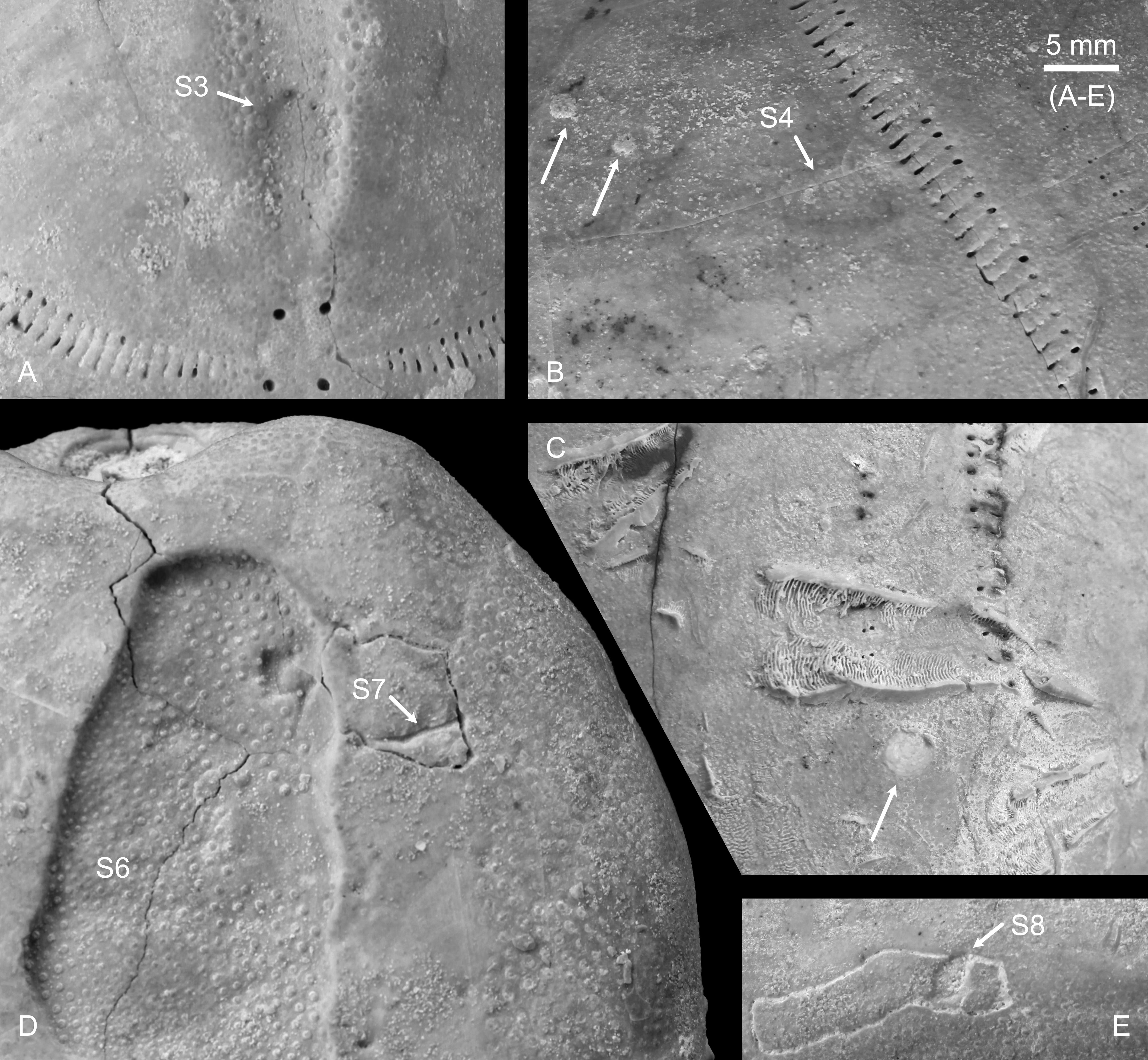

Figure 4. Hemipneustes striatoradiatus (Leske, 1778), specimen IRSNB 11513. A–E. Macrophotographs, taken in day light, showing scar details and epibionts, including bryozoans (B, arrows), bivalves (C, arrow) and the base of a serpulid, Pyrgopolon sp., on the outer test surface.

17The second pentagonal scar (S2) is located in ambulacrum V, above test mid-height, but slightly lower than S1. It measures 14.8 mm along the ambulacrum and 13.5 mm perpendicular to it. It has two straight edges, measuring each about 10 mm (the second edge cannot be measured exactly due to the presence of a serpulid tube obstructing the view). Adjacent to it is a smaller depression, less defined but similarly shaped, measuring 5.0 by 5.0 mm, situated 2.5 mm from the first. Together, these scars span a total of 20.5 mm in maximum length. The ambulacral pores of the inner and outer rows are affected; micro-CT imaging, as for S1, has shown that pores are present but externally occluded (Fig. 5C–E). The test is thinner in the scarred area, with additional stereom deposited around the internal side, smoothing over the scar (Fig. 5C, D).

Figure 5. Hemipneustes striatoradiatus (Leske, 1778), specimen IRSNB 11513. A–K. Screenshots of segmented meshes of scars S1 and S2 (A–F) and of an undescribed serpulid with a 12-keeled aragonitic tube (G–K), yielding additional insights into the healing process of S1 and S2, the internal deposition of new stereom resulted in smoothing over, and while external interruption of ambulacral pore rows is visible, pores persist internally (E, F), but are sealed externally (A–C). Colour coding: grey – outer mesh surface, green – inner mesh surface. Views A–F and H–K are non-orthogonal.

18A third depression (S3), located at the top of ambulacrum III, is shallow and elongated, measuring 9.1 mm in length and 5.1 mm in width. Similar to S1 and S2, the ambulacral pores appear disrupted externally, with slight thinning of the test within the depression.

19The fourth scar (S4) is a very shallow, elongated depression located adjacent to the tube pores of ambulacral II and mostly on interambulacral 1. It measures 7.9 mm in length and 3.3 mm in width, aligning with the plate’s length direction. Micro-CT imaging has not revealed any significant modifications to test thickness or stereom deposition around the scar.

20S3 and S4 align with S1 and S2, situated about 37.0 and 48.0 mm apart, respectively.

21The fifth scar (S5) is a small (~2.81 mm diameter) and relatively deep (~0.86 mm) pit located in the outer row of ambulacrum III, above test mid-height. Micro-CT imaging (Fig. 3D) has documented a thin layer of added stereom on its inner side. This, in combination with microtuberculation on all of its walls, suggests that it resulted from a puncture of the test.

22The large, deep scar on the adoral side (S6) measures 43.2 mm in length and 22.7 mm in width. It is situated 19.2 mm posterior to the peristome. The repaired test within the scar is thinner than the surrounding test (2.41–2.60 vs 2.65–2.89 mm) and exhibits well-preserved microtuberculation over most of its surface. A small area (~5 mm in diameter) lacks microtuberculation and a similar absence was noted on some unaffected parts of the adoral surface (Fig. 4D). The external surface of the healed area is mostly even, although there is a peculiar modification on its posterior side (Fig. 4). Internally, the healed portion of the test is not entirely flat.

23Yet another scar (S7, arrow in Fig. 4D), shaped as an elongated, narrow cut, is located adjacent to the peculiar modification of S6. It measures 7.95 mm in length, 0.59 mm in width and 0.63 mm in depth. Towards its upper side, the scar widens, with two depressions aligning it, forming a total width of 3.45 mm. Most of its trajectory lies on a seemingly ‘carved-out’ portion of the test, shaped like a parallelogram with irregular edges. Micro-CT imaging (e.g. Fig. 3I) has revealed that this ‘carving’ does not fully penetrate the test; thinner, mostly parallel cracks extend into a small point that breaches the test. Across the entire surface of the irregularly shaped rectangular area, microtuberculation is absent, as in the adjacent unscared part of the test. Possibly, all this is related to a bite of a single culprit.

24Another scar (S8, arrow in Fig. 4E), located near S7 and just above the base of the aboral side, measures 3.05 mm in length,1.55 mm in width and 0.76 mm in depth. Similar to S7, it sits on a seemingly “carved-out” portion. However, in this case, the carved-out area corresponds to a single plate. As with S7, micro-CT imaging has indicated that the scar does not completely penetrate the plate (Fig. 3E–G).

25The test is also infested with more than 20 specimens of Pyrgopolon sp., of which the attached tube portions are preserved (see Fig. 4C), nearly all located on the adoral side. At least one specimen is situated at the rim, and two small ones are hidden within the peristome depression. Small bryozoan colonies are present at several spots on the test (e.g. arrows in Fig. 4B), along with juvenile bivalves (Fig. 4C).

26Micro-CT imaging has also revealed that the internal side of the test was colonised by a sedentary polychaete with an aragonitic (now dissolved) tube with 12 keels (Figs 3H, 5G–K). The original tube thickness varied between 0.125 and 0.155 mm. The tube dimensions, measured externally, are 1.640 mm in height and 1.757 mm in width, while internally, it measures 1.456 mm in height and 1.488 mm in width.

3.2. Specimen IRSNB 11514 (Fig. 6A–E)

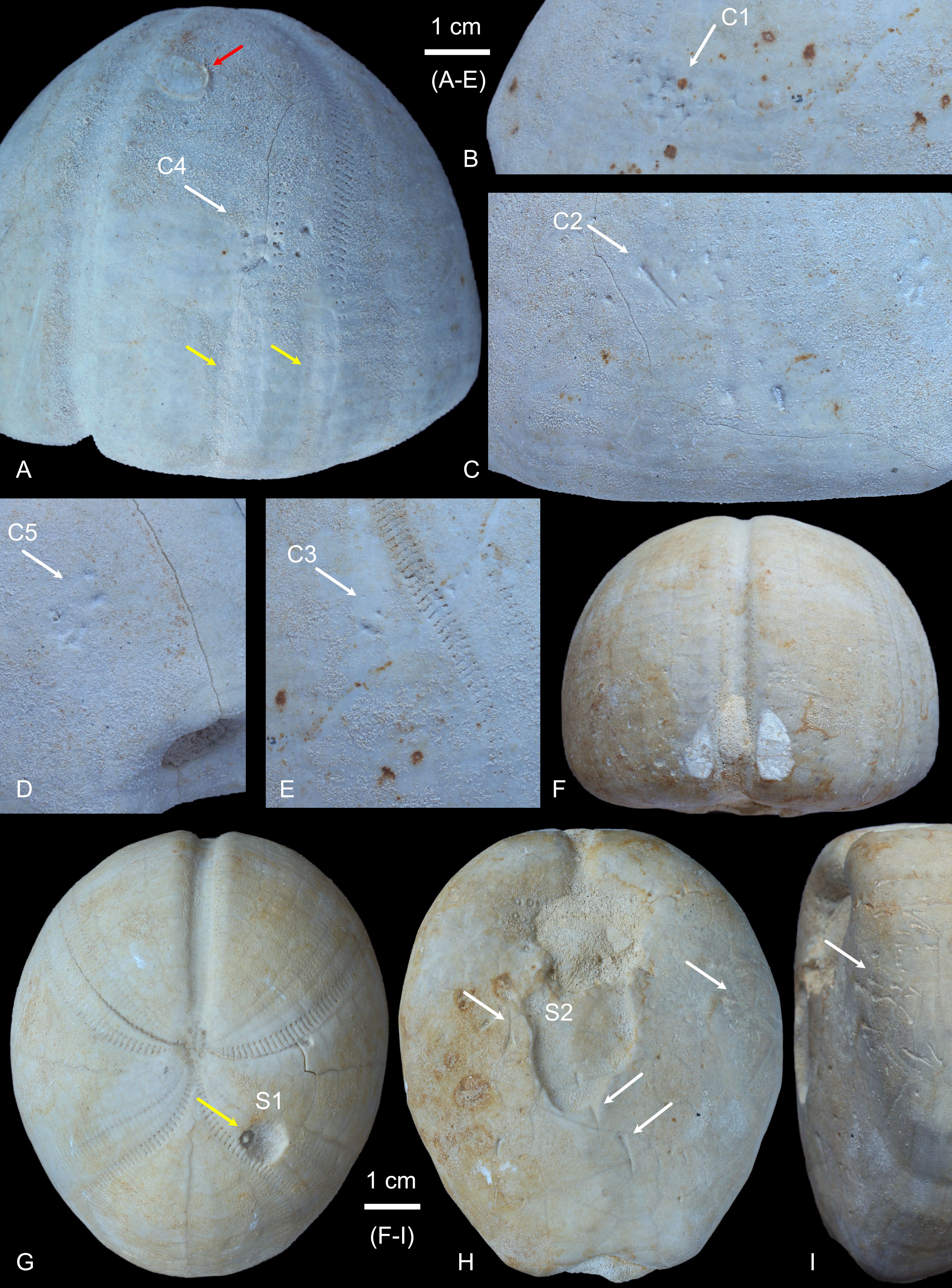

27Large-sized test, measuring 92.1 mm in length, 80.8 mm in width and 66.5 mm in height. The test is fairly well preserved, with microtuberculation present across the entire surface.

28Small, deep pits are arranged in five clusters (C1–C5) on the aboral side of the test, from mid-height to below mid-height. These pits are slightly triangular, measuring between 0.5 and 1.5 mm in size, and do not appear to penetrate the test fully. Individual pits are fairly closely spaced, mostly 2.0–3.5 mm apart (2.5–3.5 mm in C1; 2.5–5.5 mm in C2; 2.0–3.5 mm in C3; 3.3–3.5 mm in C4). Several pits feature elongated tails up to 8.9 mm in length, which become progressively shallower and narrower as they extend away from their associated pits.

29Within each cluster, the pits and tails share a similar orientation. The two largest clusters, located in ambulacrum I and interambulacrum 1 (C1), and interambulacrum 4 (C2), each contain 15–17 pits and measure approximately 23.0 mm in width, with a separation of about 71.0 mm. The tails in these clusters are oriented downwards and posteriorly, towards the periproct. Both clusters are positioned at a similar vertical height, below test mid-height.

30The third cluster (C3), containing about nine pits, is situated higher on the test, in ambulacrum II and extending into interambulacra 1 and 3. The fourth (C4) and fifth (C5) clusters, each with six pits, are located in ambulacrum IV and interambulacrum 5 and ambulacrum IV, respectively. These clusters measure about 9.5 mm in width, are separated by 71.0 mm, and are at a similar height as the first two clusters but rotated approximately 90°. The tails in the third, fourth and fifth clusters are less clearly developed, making their orientations more challenging to interpret. However, some elongation in a downward direction is still apparent. No comparable clusters or individual pits are observed on the aboral side of the test. Clusters C1 and C4 seem to form a pair, as do clusters C2 and C3, being both 180° and 78.5 and 72.5 mm apart, respectively.

31The test also features two shallow, elongated depressions on the lower part aborally (Fig. 6A, yellow arrows). One depression measures 24.4 mm in length and 6.5 mm in width, respectively, with a 9.2 mm portion of it broadening to a maximum width of 11.5 mm. The second depression measures 20.0 mm in length and 5.5 mm in width.

Figure 6. Hemipneustes striatoradiatus (Leske, 1778). A–E. Specimen IRSNB 11514, Nekum Member, Maastricht Formation, ’t Rooth quarry, Bemelen, the Netherlands, with five distinct clusters of small, deep triangular pits with tapering tails (A–E), two shallow, elongated depressions (A, yellow arrows) and an attached bivalve (A, red arrow). F–I. Specimen IRSNB 11515, Maastricht Formation, unspecified quarry, Berg en Terblijt, the Netherlands, showing scar S1 with subsequent infestation by the bioeroding organism that produced the trace Oichnus excavatus Donovan & Jagt, 2002 (G, yellow arrow), as well as scar S2 and pitting with tapering tails (F, H, I, white arrows) that also extend onto S2.

3.3. Specimen IRSNB 11515 (Fig. 6F–I)

32Medium-sized test, measuring 79,2 mm in length, 66.5 mm in width and 53.5 mm in height. Microtuberculation appears to be partially to fully effaced, and plate boundaries, particularly on the adoral side, are easily visible. It remains uncertain whether this condition is due to post-mortem and pre-burial abrasion or a combination of these natural processes and preparation.

33The test preserves a deep, medium-sized scar on the adoral side (S1), a large and deep scar on the aboral side (S2) and scattered pitting with tails in various locations. Scar S1 is located high on the test, in ambulacrum I, affecting the outer row almost entirely and the inner row partially. It has a pentagonal shape, measures 7.3 mm in diameter and is ~2.0 mm deep. Inside the scar sits a single example of the trace Oichnus excavatus Donovan & Jagt, 2002 (Fig. 6G, yellow arrow), measuring 2.9 mm in diameter (central dome ~1 mm in diameter) in its upper corner, complicating accurate interpretation of the scar’s original shape.

34The large depression scar on the adoral side is positioned posterior to the peristome and measures 21.4 by 19.4 mm. The anterior portion of the scar may be missing, with the posterior end situated 27.5 mm from the peristome. There are microtubercules preserved in the depressed part of the test.

35In addition to these scars, sharp pits are present in clusters on both the adoral side and the lower and anterior parts of the aboral side, spanning interambulacra 1 to 4. These pits measure 0.5 to 1.5 mm and are often triangular in shape, and frequently accompanied by elongated tails up to 7.0 mm in length. Individual pits are 2.0 to 3.0 mm apart, and their tails are directed away from the peristome (aboral side) and upwards (adoral side), with the maximum distance between pits on opposing side of the test being 67.0 mm. This type of pitting with tails is also observed within the depression scar posterior to the peristome and on its posterior boundary wall, but here, the tails are oriented about 90° from the other ones.

4. Discussion

4.1. Predation by mosasaurs

36The two large and deep, near-symmetrically implanted pentagonal scars S1 and S2, one of two shallower, moderately sized elongated scars (S3), plus the larger, deep scar on the adoral side (S6) in IRSNB 11513 (Figs 3, 4 and 6) are here interpreted as puncture wounds from a large-toothed vertebrate, with tooth diameters of ~11.5 mm.

37The size, shape and positioning of S1 and S2, especially their pentagonal outline with both straight and curved outer boundaries, strongly suggest these lesions were inflicted by a mosasaur, particularly one with teeth having clearly defined facets.

38In total, five mosasaur species are recorded to date from the Nekum and Meerssen members (Kuypers et al., 1998; Mulder, 1999; Jagt, 2005), namely Mosasaurus hoffmannii Mantell, 1829, Mosasaurus aff. lemonieri Dollo, 1889, Plioplatecarpus marshi Dollo, 1882 (see Fig. 7), Prognathodon aff. sectorius (Cope, 1871) and Carinodens belgicus Woodward, 1891. Of these, M. hoffmannii and P. marshi are the most common and best known (Lingham-Soliar, 1994, 1995; Street & Caldwell, 2017). From the available materials, I conclude that the teeth of P. marshi are no good match for S1 and S2 (see e.g. Fig. 7), neither in shape nor in size. Teeth of M. aff. lemonieri and P. aff. sectorius have much more elongated cross-sections, with differently placed carinae, and teeth of C. belgicus lack facets. Teeth of M. hoffmannii, the most iconic mosasaur from the Maastrichtian type area, particularly the premaxillary teeth, provide the best match for these punctures. The spacing between S2 and S3 also matches that seen between the front and inner teeth rows in M. hoffmannii, as in IRSNB R12 (approximately, both teeth of the second row are missing) and IRSNB R25 (only the two right premaxillary teeth preserved), two of the best-preserved premaxillae of this species from the type Maastrichtian (Lingham-Soliar, 1995; Street & Caldwell, 2017). Specimen IRSNB R12 also demonstrates that the gape between the left and right teeth of the frontal row of the maxilla is already too wide to account for S1 and S2. Scar S4, which does not show test puncture, may be unrelated to the attack. Specimen NHMM 006696, a very large premaxilla for the species, further indicates that the attacker was not a giant M. hoffmanni, as tooth spacing in this specimen is already much wider, both between the left and right teeth and front and second tooth rows. This is to some extent remarkable, seeing that teeth of M. hoffmannii are generally classified within the crush, rather than the pierce, guild, to which P. marshi belongs (e.g. Giltaij et al., 2021; Bardet et al., 2025).

Figure 7. 3D renders and virtual sections of an upper jaw tooth (A–H) and a lower jaw tooth (I–P) of Plioplatecarpus marshi Dollo, 1882 (IRSNB R0039; see also Lingham-Soliar, 1994, fig. 12A–B, fourth from left, and fig. 12C–D, first from left respectively).

39The combined presence of premaxillary-teeth-inflicted punctures and scar S6, the latter large enough to accommodate two successive teeth of the lower jaw, suggests an attack from above, consistent with the semi-infaunal mode of life of Hemipneustes, ploughing very shallowly through the muddy seafloor. Scar healing indicates that the attack was non-lethal; the echinoid test was abandoned, for whatever reason, after the first bite.

40This is the first unequivocal instance of mosasaur predation on Hemipneustes, and more generally, on echinoids from the Maastrichtian type area (Jagt et al., 2018; Neumann & Hampe, 2018). Earlier attributions, such as Dollo’s (1913) reference to a test of Hemipneustes found on skeletal remains of C. belgicus, are invalidated by stratigraphical superposition and lack of damage (Jagt, in Neumann & Hampe, 2018). Donovan et al. (2008) reflected on a mosasaur origin of a healed pentagonal scar in Hemipneustes but considered it doubtful. Both Neumann & Hampe (2018) and Jagt et al. (2018) dismissed mosasaur predation, mostly for lack of evidence. These conclusions can now be revised.

41Another example that warrants re-evaluation is the pentagonal scar on a test of Echinocorys gr. conoidea Goldfuss, 1829 from the former CPL SA quarry (Haccourt-Lixhe area, Belgium; now Kreco) described by Donovan et al. (2010; NHMM 2009 005, Lixhe 1 Member, Gulpen Formation, Maastrichtian; Fig. 1). Its complex margins, including folded areas inside the circumference, were attributed to syn vivo colonisation of a soft, sessile invertebrate, such as a sea anemone. However, its outer pentagonal shape strongly resembles scars S1 and S2 in IRSNB 11513 as illustrated here, suggesting an original bite, possibly later colonised. The absence of some of the tuberculation may, as suggested by Donovan et al. (2010), reflect such secondary occupation. However, the distance to tube feet is refuted here as a criterion to favour colonisation over puncture as done by Donovan et al. (2010). Future micro-CT imaging of NHMM 2009 005 might clarify the nature of this pentagonal scar.

42Beyond this, only one other echinoid from the European Upper Cretaceous bears evidence of a mosasaur attack: a fragmentary Echinocorys ovata Leske, 1778 from the Maastrichtian of Hemmoor, northern Germany, as described by Neumann & Hampe (2018). This test has four healed punctures on the aboral side, that were interpreted as having been inflicted by the premaxilla of a prognath marine reptile, likely a globidensine mosasauroid such as Prognathodon.

43Neumann & Hampe (2018) also discussed the paucity of evidence for mosasaur predation on large echinoids from the European Upper Cretaceous. An important factor to add to this is tooth size, in combination with dental guilds (see e.g. Giltaij et al., 2021). For instance, the teeth of large adult M. hoffmannii are too widely spaced to leave paired punctures and, on account of their cutting guild assignment, would likely have shattered the test entirely. Similarly, while the durophagous C. belgicus (Schulp, 2005) has smaller and more closely spaced teeth, these are of the crushing guild type and would presumably not produce discrete punctures that fully resemble the shape of the teeth. Only young mosasaurs or those with piercing guild premaxillary or front teeth are small enough and appropriately shaped to leave identifiable puncture marks. Most mosasaurs would thus likely destroy the test completely or swallow it whole, leaving no diagnostic traces and only fragments, which are often overlooked or discarded during fieldwork. Of note in this respect is that I have observed large tests of Hemipneustes that appeared bisected but did not show any signs of abrasion or transport, although their interpretation remains uncertain.

44Specimen IRSNB 11515 may represent another case of echinoid survival following mosasaur predation. This test bears a large scar (S1) similar to S6 in IRSNB 11513 on its aboral side, along with a healed pentagonal puncture (S1) on its adoral side. Although smaller and slightly different in shape, the pentagonal scar is consistent with tooth morphology and again suggests an attack from above. The smaller size of both test and scars point towards a different predator, possibly P. marshi, which has teeth typical of the piercing guild (see also Fig. 7 for cross sections). In this, the difference between adoral puncturing and aboral crushing in both specimens may have resulted from the combined effects of impact angle (domed adoral vs flattened aboral side) and the lower jaw having the lead bite.

45If corroborated by further research, this would suggest that many large, healed scars on the aboral or lower part of the adoral sides of Hemipneustes striatoradiatus represent previously ignored evidence of mosasaur predation.

46Irrespective of type of predator(s), localised test healing is known to be a common physiological response amongst holasteroid echinoids, and echinoids in general, both in the fossil record and in extant taxa (e.g. Hamel et al., 2021; Petsios et al., 2023). Micro-CT imaging of IRSNB 11513 has provided further insight into the healing process. New stereom was deposited over an area larger than the original wound, restoring test’s integrity and producing localised thickening around the scar, with a slightly sunken repaired surface. This process also smoothed over the inner surface of the test, as shown in Figure 5A–F. In scars S1 and S2, the imaging reveals partial regeneration of tube feet pores, although several appear closed on the outer surface.

4.2. Predation by sharks

47The small, deep triangular pits with tails arranged in clusters, observed in IRSNB 11514 and IRSNB 11515, are interpreted as bite marks inflicted by a toothed vertebrate, likely a bony or cartilaginous fish. These bites were probably non-lethal, as the pits did not penetrate the test. However, the absence of tuberculation or other signs of test healing suggests that both echinoids may have died shortly after the attack. For IRSNB 11515, although considered unlikely, the possibility that the missing portion of the test near the peristome can be linked to the same attack cannot be ruled out entirely.

48In IRSNB 11514, at least two successive bites are evident. The direction of the tails suggests an attack from above. Clusters C1 and C2, with the highest number of pits and positioned slightly lower on the test than their opposing clusters C4 and C3, are interpreted as marks from the lower jaw, while the upper jaw caused the other clusters. The tails are also more pronounced in C1 and C2, indicative of the lower jaw having the lead bite. The size and arrangement of the pits suggest that the teeth were small, sharp, non-serrated, narrow-tipped and closely spaced (2.5–3.5 mm apart). Gaps up to 5.0 mm may reflect incomplete contact or missing teeth. The possibility of multiple rows of teeth is also considered. The attacker would have needed a jaw gape of at least 78.5 mm.

49In contrast, IRSNB 11515 shows bite traces on the lower third of its adoral side and a significant portion of its aboral side. Like IRSNB 11515, at least two bites are inferred, with successive bites forming a 90° angle. The main bite, from above, responsible for the majority of the pits, positioned the echinoid in the mouth along the middle and anterior part of the flanks of the test at a 70° angle to its length axis. Pit spacing (2.0–3.0 mm) is similar to IRSNB 11514, although more pits and tails are present, possibly due to three rows of teeth or three repeats of the same bite. Tails are better developed near ambulacrum IV than II, suggesting lower jaw impact in the former and upper jaw in the latter. This bite required a jaw gape of at least 67.0 mm. For the second bite, presumed to have occurred at a 90° angle to the first, the lower jaw impacted the middle of the aboral side posterior to the peristome, the upper jaw may have left no traces.

50Both specimens were likely grabbed by a medium-sized predator with small, sharp, closely spaced, non-serrated teeth that are erect rather than (strongly) inclined. This matches sharks such as Palaeogaleus faujasia van de Geyn, 1937, well known from the Maastrichtian of the study area. This interpretation supports the possibility that the pitting, especially in IRSNB 11515, may have been caused by multiple rows of teeth. However, other sharks and even bony fishes cannot be excluded as potential culprits. Both are well represented in the Maastrichtian deposits of the area (e.g. Herman, 1977; Reynders, 1998; Friedman, 2012; Taverne & Goolaerts, 2015; Wallaard et al., 2019, 2024; Barten & Jagt, 2024; Barten et al., 2024c).

51The predator likely employed a consistent strategy: attacking from above, which is consistent with the semi-infaunal mode of life of Hemipneustes, and inflicting at least two bites, with a 90° rotation of the echinoid test between bites. The attacker may have let go of both specimens after the second or third bite (C5 in IRSNB 11514).

52Previously, Donovan & Jagt (2020b) described a test of Hemipneustes with two clusters of up to 15 deep, parallel grooves in trapezoid groupings on opposite sides of the test. These grooves did not fully penetrate the test, although a 20-mm-diameter section of test was missing in one cluster, attributed to damage post-dating the attack, possibly even from excavating the fossil. The attack was interpreted as non-lethal, but the absence of tuberculation at the base of the grooves suggested rapid death after the attack. These authors suggested a non-durophagous shark, possibly a scyliorhinid or squalid, as the predator, although some teleosts (e.g. aspidorhynchids, saurodontids, ichthyotringids) could not be ruled out. Only a single bite was recorded on that specimen, also clearly from a larger and stronger predator with larger teeth capable of penetrating much more deeply into the echinoid test than in the two specimens recorded herein.

53Apart of this test and the two new specimens, I am not aware of any other example(s) of shark predation on Hemipneustes or other Maastrichtian type area echinoids in the scientific literature. However, presumed fish predation on Echinocorys from the Gulpen Formation was noted by Dortangs (1998) and Jagt et al. (2018), as well as on tests of Echinocorys from the Campanian–Maastrichtian of Germany (Gripp, 1929; Thies, 1985; Frerichs,1987; Jagt et al., 2018; Girod et al., 2023). However, these traces differ, showing scoop-like grating around the ambitus, likely arising from attempts to lift the echinoid off the seafloor between the predator’s lower and upper jaws (Jagt et al., 2018). Clearly, the rather meagre evidence available does underscore the diversity of Late Cretaceous predator-prey dynamics.

54Tests of large holasteroids with shark predation marks remain exceedingly rare. Whether this reflects a biological reality or taphonomic loss is uncertain. Yet, a specimen suggesting survival of an earlier mosasaur attack followed by being bitten by a shark did somehow survive, both burial and excavation. Successful predation may destroy the test entirely, and erosion or healing may obscure bite evidence. No shark coprolites or shark tooth enamel isotope studies are yet available from the Maastrichtian type area to yield further information on the identity of the predator(s).

4.3. Interactions with other organisms

55Our three specimens further show that tests of Hemipneustes were commonly used as hard substrates by sessile benthos, including encrusting bivalves (Figs 4C, 6A), bryozoans and benthic foraminifera (Fig. 4B) and serpulids (Fig. 4C), confirming previous analyses. Micro-CT imaging of IRSNB 11513 (Figs 3H, 5G–K) has revealed a potentially new serpulid species, characterised by a 12-keeled aragonitic tube, distinct from any species recorded by Jäger (2012). Scar S8 in IRSNB 11513 (Figs 3E–G, 4E) remains difficult to interpret; it may have resulted from an unknown invertebrate, yet it bears some resemblance to traces attributed to encrusting foraminifera or acrothoracican cirripedes such as Rogerella de Saint-Seine, 1951 (e.g., Donovan & Jagt, 2013b; Donovan et al., 2015; Jagt et al., 2018, figs 11, 12). Alternatively, it may be a case of bald sea urchin disease (Johnson, 1971) (J.W.M. Jagt, pers. comm., August 2025).

56Another peculiar feature of IRSNB 11515 may be of interest, namely the presence of the bioerosional trace Oichnus excavatus within the healed puncture scar S1 (Fig. 6G). In combination with the smaller test size, colour and preservational details, this suggests that this test originated from the Meerssen Member (Defour et al., 1994; Donovan & Jagt, 2002, 2004, 2005). As documented by Donovan et al. (2018), even a total of 170 examples of the trace O. excavatus may have been non-lethal for Hemipneustes. Yet, as far as I am aware, IRSNB 11515 presents the first example of this trace type within the healed puncture of a test of Hemipneustes.

5. Conclusions

57Newly documented cases of vertebrate predation on the holasteroid echinoid Hemipneustes striatoradiatus provide direct insights into the complexity of predator-prey interactions in the latest Maastrichtian shallow-marine ecosystems of the Belgian-Dutch chalk shelf. They demonstrate that these large echinoids were actively targeted by multiple vertebrate taxa, despite the mechanical challenges posed by their robust tests. The new findings require a reassessment of previous assumptions about the rarity or absence of such interactions, particularly involving mosasaurs, and suggest that the fossil record may significantly underrepresent such events due to preservation and collection biases.

58The present examples document the first unequivocal evidence of mosasaur predation on Hemipneustes, the first ever for an echinoid from the type area of the Maastrichtian Stage, and only the second on a global scale. The shape and size of the two peculiar symmetrically implanted scars remarkably point to Mosasaurus hoffmannii, the teeth of which are generally classified as crush, rather than pierce guild. A possible second specimen from the Maastrichtian type area is also discussed, possibly having been preyed upon by Plioplatecarpus marshi. Both survived the attack, becoming liberated after the first bite, and healing the punctured parts of the test by adding stereom. Remarkably, the common presence of a large, healed scar on the aboral side, one observed in many more Hemipneustes, suggests mosasaur predation on Hemipneustes to have been much commoner than previously assumed.

59These specimens also document two more cases of attacks by neoselachians. Until now, only a single shark attack was recorded from the Maastrichtian type area. All examples yield insights into the predator’s modus operandi and behaviour. The shark-bitten tests show traces of more than a single attempt during which the echinoid was overturned in between successive bites.

60The present specimens show that Hemipneustes played a critical role in the late Maastrichtian trophic web, as a semi-infaunal deposit feeder, as prey to apex and mesopredators and by offering available substrate for syn vivo and post-mortem colonisation by a diverse array of invertebrates. The present study also documents the power of the application of non-destructive techniques, such as micro-CT imaging, combined with detailed comparative tooth morphology, in further attempts at resolving predator identity and biomechanics behind these interactions.

Acknowledgements

61I wish to thank Jacques Severijns (Maastricht, the Netherlands), Robert Pieters (Geel, Belgium), Nadine Robert (Holsbeek, Belgium) and Piotr Menducki (Poland) for bringing these specimens to my attention. This study benefitted from the DIGIT program, for the micro-CT imaging of IRSNB 11513 (executed by myself) and of the two teeth of Plioplatecarpus marshi IRSNB R0039 (executed by Camille Locatelli, who is warmly thanked). Object Research Systems (ORS, www.theobjects.com) and GOM are acknowledged for providing non-commercial access to their Dragonfly ORS and GOM Inspect (version 2019) software packages. Cecilia Cousin is thanked for access to the RBINS vertebrate fossil collection, Annelise Folie and Julien Lalanne for curational assistance. Dylan Bastiaans (NHMM) is thanked for access to mosasaur fossils in the NHMM collection and for discussions on tooth morphology and modes of attack. Dirk Cornelissen (NHMM) is thanked for valuable insights in Mosasaurus hoffmanni. Indirectly, this study largely benefitted from field trips to the Maastrichtian type area organised by the ‘Nederlandse Geologische Vereniging afdeling Limburg’, the ‘Werkgroep Krijt en Vuursteen’ and others, and all participants who showed their finds to me. All owners of Maastrichtian type area quarries are also thanked for granting access for research. Reviewers John W.M. Jagt (NHMM) and Christian Klug (Paläontologisches Institut und Museum der Universität Zürich, Zurich, Switzerland) are thanked for their helpful comments allowing to improve the quality of the manuscript.

Data availability

62All specimens studied are housed in official repositories guaranteeing their long-term safekeeping and availability to other researchers for future studies. The original micro-CT imaging data of IRSNB 11513 and the two teeth of IRSNB R0039 can be obtained upon request from the RBINS palaeontology collection manager.

References

63Assemat, A., Adnet, S. & Martin, J.E., 2025. Reconstructing the trophic structure of Maastrichtian elasmobranch communities in Morocco using calcium isotopes. Gondwana Research, 146, 228–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gr.2025.05.021

64Bardet, N., Fischer, V., Jalil, N.-E., Khaldoune, F., Yazami, O.K., Pereda-Suberbiola, X. & Longrich, N., 2025. Mosasaurids bare the teeth: an extraordinary ecological disparity in the phosphates of Morocco just prior to the K/Pg crisis. Diversity, 17, 114. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17020114

65Barten, L.P.J. & Jagt, J.W.M., 2024. Rarer than rare: articulated and associated remains of Late Cretaceous cartilaginous fish from Liège-Limburg (Belgium, the Netherlands). In Jagt, J.W.M., Jagt-Yazykova, E.A., del Prado-Rebordinos, A. & Teschner, E.M. (eds), The 175th Anniversary of the Maastrichtian – a Celebratory Meeting Maastricht, September 8-11, 2024, Abstract Volume and Programme, 15–18.

66Barten, L.P.J., Jagt, J.W.M. & Mulder, E., 2024a. Gut contents of a subadult individual of Mosasaurus hoffmannii Mantell, 1829 from the Maastrichtian type area (the Netherlands) hint at the species’ dietary preferences. In Jagt, J.W.M., Jagt-Yazykova, E.A., del Prado-Rebordinos, A. & Teschner, E.M. (eds), The 175th Anniversary of the Maastrichtian – a Celebratory Meeting Maastricht, September 8-11, 2024, Abstract Volume and Programme, 23–26.

67Barten, L.P.J., Deckers, M.J.M. & Jagt, J.W.M., 2024b. Zee-egels op het menu in de Limburgse Krijtzee – een paar sprekende voorbeelden. Conglomeraat, 1/4, 162–165.

68Barten, L.P.J., Jagt, J.W.M. & Severijns, J., 2024c. More than just jaws – the pycnodontiform fish genus Anomoeodus from the Maastrichtian type area. In Jagt, J.W.M., Jagt-Yazykova, E.A., del Prado-Rebordinos, A. & Teschner, E.M. (eds), The 175th Anniversary of the Maastrichtian – a Celebratory Meeting Maastricht, September 8-11, 2024, Abstract Volume and Programme, 19–22.

69Cope, E.D., 1871. Supplement to the ‘Synopsis of the extinct Batrachia and Reptilia of North America’. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 12, 41–52.

70Defour, E., Geussens, T., Indeherberge, L. & Strijbos, V., 1994. Vormvariaties van Hemipneustes striatoradiatus en Hemiaster prunella uit het Boven-Krijt van Limburg. LIKONA Jaarboek, 93, 7–14.

71de Saint-Seine, R., 1951. Un cirripède acrothoracique du Crétacé : Rogerella lecointrei, n. g., n. sp. Comptes Rendus hebdomadaires des Séances de l’Académie des Sciences, Paris, 233, 1051–1053.

72Dollo, L., 1882. Note sur l’ostéologie des Mosasauridae. Bulletin du Musée royal d’Histoire naturelle de Belgique, 1, 55–80.

73Dollo L., 1889. Première note sur les Mosasauriens de Mesvin. Bulletin de la Société belge de Géologie, de Paléontologie et d’Hydrologie, 3, 271-304.

74Dollo, L., 1913. Globidens Fraasi, mosasaurien mylodonte nouveau du Maestrichtien (Crétacé supérieur) du Limbourg, et l’éthologie de la nutrition chez les mosasauriens. Archives de Biologie, 28, 609–626 [1–18].

75Donovan, S.K. & Jagt, J.W.M., 2002. Oichnus Bromley borings in the irregular echinoid Hemipneustes Agassiz from the type Maastrichtian (Upper Cretaceous, The Netherlands and Belgium). Ichnos, 9, 67–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/10420940190034139

76Donovan, S.K. & Jagt, J.W.M., 2004. Taphonomic and ethologic aspects of the ichnology of the Maastrichtian of the type area (Upper Cretaceous, The Netherlands and Belgium). Bulletin de l’Institut royal des Sciences naturelles de Belgique, Sciences de la Terre, 74, 119–127.

77Donovan, S.K. & Jagt, J.W.M., 2005. An additional record of Oichnus excavatus Donovan & Jagt from the Maastrichtian (Upper Cretaceous) of southern Limburg, The Netherlands. Scripta Geologica, 129, 147–150.

78Donovan, S.K. & Jagt, J.W.M., 2009. Fossil sea urchins as hard substrates. Deposits, 20, 14–17.

79Donovan, S.K. & Jagt, J.W.M., 2013a. Site selectivity of the pit Oichnus excavatus Donovan and Jagt infesting Hemipneustes striatoradiatus (Leske) (Echinoidea) in the type Maastrichtian (Upper Cretaceous, The Netherlands). Ichnos, 20, 112–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/10420940.2013.815616

80Donovan, S.K. & Jagt, J.W.M., 2013b. Rogerella isp. infesting the pore pairs of Hemipneustes striatoradiatus (Leske) (Echinoidea: Upper Cretaceous, Belgium). Ichnos, 20, 153–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/10420940.2013.845098

81Donovan, S.K. & Jagt, J.W.M., 2014. Ichnology of Late Cretaceous echinoids from the Maastrichtian type area (The Netherlands, Belgium) – 3. Podichnus Bromley and Surlyk and a crinoid attachment on the echinoid Echinocorys Leske from the Lixhe area, Belgium. Bulletin of the Mizunami Fossil Museum, 40, 75–78.

82Donovan, S.K. & Jagt, J.W.M., 2018. Big oyster, robust echinoid: an unusual association from the Maastrichtian type area (province of Limburg, southern Netherlands). In Meyer, C.A., Thuy, B., Klug, C., Marty, D. & Donovan, S.K. (eds), Hans Hess: A lifelong passion for fossil echinoderms. Swiss Journal of Palaeontology, 137, 357–361. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13358-018-0151-3

83Donovan, S.K. & Jagt, J.W.M., 2020a. Oichnus simplex Bromley infesting Hemipneustes striatoradiatus (Leske) (Echinoidea) from the Maastrichtian type area (Upper Cretaceous, The Netherlands). Ichnos, 27, 64–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/10420940.2019.1584561

84Donovan, S.K. & Jagt, J.W.M., 2020b. Ichnology of Late Cretaceous echinoids from the Maastrichtian type area (The Netherlands, Belgium) – 4. Shark versus echinoid: failed predation on the holasteroid Hemipneustes. Bulletin of the Mizunami Fossil Museum, 47, 49–57.

85Donovan, S.K., Jagt, J.W.M. & Lewis, D.N., 2008. Ichnology of Late Cretaceous echinoids from the Maastrichtian type area (The Netherlands, Belgium) – 1. A healed puncture wound in Hemipneustes striatoradiatus (Leske). Bulletin of the Mizunami Fossil Museum, 34, 73–76.

86Donovan, S.K., Jagt, J.W.M. & Dols, P.P.M.A., 2010. Ichnology of Late Cretaceous echinoids from the Maastrichtian type area (The Netherlands, Belgium) – 2. A pentagonal attachment scar on Echinocorys gr. conoidea (Goldfuss). Bulletin of the Mizunami Fossil Museum, 36, 51–53.

87Donovan, S.K., Jagt, J.W.M. & Goffings, L., 2014. Bored and burrowed: an unusual echinoid steinkern from the Type Maastrichtian (Upper Cretaceous, Belgium). Ichnos, 21, 261–265. https://doi.org/10.1080/10420940.2014.955097

88Donovan, S.K., Jagt, J.W.M. & Langeveld, M., 2018. A dense infestation of round pits in the irregular echinoid Hemipneustes striatoradiatus (Leske) from the Maastrichtian of the Netherlands. Ichnos, 25, 25–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/10420940.2017.1345736

89Donovan, S.K., Jagt, J.W.M. & Nieuwenhuis, E., 2015. Site selectivity of the boring Rogerella isp. infesting Cardiaster granulosus (Goldfuss) (Echinoidea) in the type Maastrichtian (Upper Cretaceous, Belgium). Geological Journal, 51/5 (pro 2016), 789–793. https://doi.org/10.1002/gj.2692

90Dortangs, R., 1998. Sporenfossielen. In Jagt, J.W.M., Laloux, J. & Dhondt, A.V. (eds), Limburgnummer 9B: Fossielen van de St. Pietersberg. Grondboor & Hamer, 52/4-5, 150–151.

91Ekdale, A.A., 1985. Paleoecology of the marine endobenthos. Palaeogeography, Palaeoecology, Palaeoclimatology, 50, 63–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0031-0182(85)80006-7

92Felder, W.M., 1975. Lithostratigrafie van het Boven-Krijt en het Dano-Montien in Zuid-Limburg en het aangrenzende gebied. In Zagwijn, W.H. & van Staalduinen, C.J. (eds), Toelichting bij geologische overzichtskaarten van Nederland. Rijks Geologische Dienst, Haarlem, 63–72.

93Felder, W.M. & Bosch, P.W., 2000. Geologie van Nederland, Deel 5. Het Krijt van Zuid-Limburg. NITG-TNO, Utrecht/Delft, 190 p.

94Fischer, V., Weis, R., Delsate, D.F., Giustina, F.D., Wintgens, P., Fuchs, D. & Thuy, B., 2025. Vampyromorph coleoid predation by an ichthyosaurian from the Early Jurassic Lagerstätte of Bascharage, Luxembourg. PeerJ, 13, e19786 http://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.19786

95Frerichs, U., 1987. Über Anomalien bei irregulären Seeigeln aus dem Campan im Raum Hannover. Arbeitskreis Paläontologie Hannover, 15/6, 121–125.

96Friedman, M., 2012. Ray-finned fishes (Osteichthyes, Actinopterygii) from the type Maastrichtian, the Netherlands and Belgium. In Jagt, J.W.M., Donovan, S.K. & Jagt-Yazykova, E.A. (eds), Fossils of the type Maastrichtian, Part 1. Scripta Geologica Special Issue, 8, 113–142.

97Giltaij, T.J., van der Lubbe, J.H.J.L., Lindow, B.E.K., Schulp, A.S. & Jagt, J.W.M., 2021. Carbon isotope trends in north-west European mosasaurs (Squamata; Late Cretaceous). Bulletin of the Geological Society of Denmark, 69, 59–70. https://doi.org/10.37570/bgsd-2021-69-04

98Girod, P., Wisshak, M. & Rösner, T., 2023. Spurenfossilien (Ichnofossilien). In Schneider, C. & Girod, P. (eds), Fossilien aus dem Campan von Hannover, 4., komplett überarbeitete und erweiterte Auflage. Arbeitskreis Paläontologie Hannover, Hannover, 654–686.

99Goldfuss, A. 1829. Petrefacta Germaniae, tam ea, quae in museo universitatis regiae Borussicae Fridericiae Wilhelmiae Rhenanae servantur, quam alia quae cunque in museis hoeninghausiano, muensteriano aliisque, extant, iconibus et descedentarias illustrata. Abbildungen und Beschreibungen der Petrefacten Deutschlands und der angränzenden Länder, unter Mitwirkung des Herrn Grafen Georg zu Münster, herausgegeben von August Goldfuss. Arnz and Co., Düsseldorf, 77–164.

100Gripp, K., 1929. Über Verletzungen an Seeigeln aus der Kreide Norddeutschlands. Paläontologische Zeitschrift, 11, 238–245. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03042728

101Hamel, J.-F., Jobson, S., Caulier, G. & Mercier, A., 2021. Evidence of anticipatory immune and hormonal responses to predation risk in an echinoderm. Scientific Reports, 11, 10691. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-89805-0

102Herman, J., 1977. Les sélaciens des terrains néocrétacés & paléocènes de Belgique & des contrées limitrophes. Eléments d’une biostratigraphie intercontinentale. Mémoires pour servir à l’Explication des Cartes géologiques et minières de la Belgique, 15 (pro 1975), 5–401.

103Hoffmann, R., Stevens, K., Keupp, H., Simonsen, S. & Schweigert, G., 2019. Regurgitalites – a window into the trophic ecology of fossil cephalopods. Journal of the Geological Society, 177/1, 82–102. https://doi.org/10.1144/jgs2019-117

104Holwerda, F.M., Bestwick, J., Purnell, M.A., Jagt, J.W.M. & Schulp, A.S., 2023. Three-dimensional dental microwear in type-Maastrichtian mosasaur teeth (Reptilia, Squamata). Scientific Reports, 13, 18720. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-42369-7

105Hunt, A.P. & Lucas, S.G., 2025. Regurgitalites. In Lucas, S.G., Hunt, A.P. & Klein, H. (eds), Vertebrate Ichnology: Track and Trails, Consumption, Digging and Reproduction, Geoconservation. Elsevier, Amsterdam, 381–404. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-443-38351-9.00009-8

106Huygh, J.J.C., Sinnesael, M., Kaskes, P., Vellekoop, J., Van der Geest, H., Jagt, J.W.M. & Claeys, P., 2025. Flint formation and astronomical pacing in the Maastrichtian chalk of northwestern Europe. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 675, 113095. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2025.113095

107Jäger, M., 2012. Sabellids and serpulids (Polychaeta sedentaria) from the type Maastrichtian, the Netherlands and Belgium. In Jagt, J.W.M., Donovan, S.K. & Jagt-Yazykova, E.A. (eds), Fossils of the type Maastrichtian, Part 1. Scripta Geologica Special Issue, 8, 45–81.

108Jagt, J.W.M., 2000. Late Cretaceous-Early Palaeogene echinoderms and the K/T boundary in the southeast Netherlands and northeast Belgium – Part 4: Echinoids. Scripta Geologica, 121, 181–375.

109Jagt, J.W.M., 2005. Stratigraphic ranges of mosasaurs in Belgium and the Netherlands (Late Cretaceous) and cephalopod-based correlations with North America. In Schulp, A.S. & Jagt, J.W.M. (eds), Proceedings of the First Mosasaur Meeting. Netherlands Journal of Geosciences – Geologie en Mijnbouw, 84/3, 283–301. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0016774600021065

110Jagt, J.W.M., 2021. Paleontologie in Limburg: van de 18de-eeuwse kiem tot de dag van vandaag. Grondboor & Hamer, 75/1, 8–18.

111Jagt, J.W.M. & Jagt-Yazykova, E.A., 2012. Stratigraphy of the type Maastrichtian – a synthesis. In Jagt, J.W.M., Donovan, S.K. & Jagt-Yazykova, E.A. (eds), Fossils of the type Maastrichtian, Part 1. Scripta Geologica Special Issue, 8, 5–32.

112Jagt, J.W.M., van Bakel, B.W.M., Deckers, M.J.M., Donovan, S.K., Fraaije, R.H.B., Jagt-Yazykova, E.A., Laffineur, J., Nieuwenhuis, E. & Thijs, B., 2018. Late Cretaceous echinoderm ‘odds and ends’ from the Low Countries. Contemporary Trends in Geosciences, 7, 255–282.

113Jagt, J.W.M., Claessens, L.P.A.M., Fraaije, R.H.B., Jagt-Yazykova, E.A., Mulder, E.W.A., Schulp, A.S. & Wallaard, J.J.W., 2024a. The Maastrichtian type area (Netherlands-Belgium): a synthesis of 250+ years of collecting and ongoing progress in Upper Cretaceous stratigraphy and palaeontology. In Clary, R.M., Pyle, E.J. & Andrews, W.M. (eds), Geology’s significant Sites and their Contributions to Geoheritage. Geological Society, London, Special Publications, 543, 281–294. https://doi.org/10.1144/SP543-2022-232

114Jagt, J.W.M., Deckers, M.J.M. & Jagt-Yazykova, E.A., 2024b. ‘Changing of the guard’ amongst holasteroid echinoids in the upper Maastrichtian of the south-east Netherlands: exit Echinocorys, enter Hemipneustes. Cretaceous Research, 158, 105850. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cretres.2024.105850

115Jain, S., Salamon, M.A., Klug, C., Lomax, D.R., Płachno, B.J. & Duda, P., 2025. An unusual predator-prey relationship inferred from a Bathonian (Middle Jurassic) nautilid from southern Poland. Lethaia, 58/3, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.18261/let.58.3.5

116Johnson, P.T., 1971. Studies on diseased urchins from Point Loma. In North, W.J. (ed.), Kelp Habitat Improvement Project. Annual Report 1970–1971, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, 82–90.

117Kauffman, E.G., 2004. Mosasaur predation on Upper Cretaceous nautiloids and ammonites from the United States Pacific coast. Palaios, 19, 96–100. https://doi.org/10.1669/0883-1351(2004)019<0096:MPOUCN>2.0.CO;2

118Kauffman, E.G. & Kesling, R.V., 1960. An Upper Cretaceous ammonite bitten by a mosasaur. Contributions from the Museum of Paleontology, The University of Michigan, 15/9, 193–248.

119Keupp, H., 2012. Atlas zur Paläopathologie der Cephalopoden. Berliner paläobiologische Abhandlungen, 12, 1–391.

120Klug, C., Schweigert, G., Hoffmann, R., Weiss, R. & De Baets, K., 2021. Fossilized leftover falls as sources of palaeoecological data: a ‘pabulite’ comprising a crustacean, a belemnite and a vertebrate from the Early Jurassic Posidonia Shale. Swiss Journal of Palaeontology, 140, 10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13358-021-00225-z

121Kuypers, M.M.M., Jagt, J.W.M., Peeters, H.H.G., de Graaf, D.Th., Dortangs, R.W., Deckers, M.J.M., Eysermans, D., Janssen, M.J. & Arpot, L.,1998. Laat-kretaceische mosasauriers uit Luik-Limburg. Nieuwe vondsten leiden tot nieuwe inzichten. Publicaties van het Natuurhistorisch Genootschap in Limburg, 41/1, 5–47.

122Leske, N.G., 1778. Jacobi Theodori Klein Naturalis dispositio Echinodermatum, edita et descriptionibus novisque inventis et synonymis auctorum aucta. G.E. Beer, Lipsiae, 278 p.

123Lingham-Soliar, T., 1994. The Mosasaur Plioplatecarpus (Reptilia, Mosasauridae) from the Upper Cretaceous of Europe. Bulletin de l’Institut royal des Sciences naturelles de Belgique, Sciences de la Terre, 64, 177–211.

124Lingham-Soliar, T., 1995. Anatomy and functional morphology of the largest marine reptile known, Mosasaurus hoffmanni (Mosasauridae, Reptilia) from the Upper Cretaceous, Upper Maastrichtian of the Netherlands. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, London, B. Biological Sciences, 347, 155–180. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.1995.0019

125Lingham-Soliar, T. & Nolf, D., 1990. The mosasaur Prognathodon (Reptilia, Mosasauridae) from the Upper Cretaceous of Belgium. Bulletin de l’Institut royal des Sciences naturelles de Belgique, Sciences de la Terre, 59 (pro 1989), 137–190.

126Mantell, G., 1829. A tabular arrangement of the organic remains of the county of Sussex. Transactions of the Geological Society of London, Series 2, 3, 201–216. https://doi.org/10.1144/transgslb.3.1.201

127Melville, R.V. & Durham, J.W., 1966. Skeletal morphology. In Moore, R.C. (ed.), Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology, Part U, Echinodermata 3. The Geological Society of America, Boulder, the University of Kansas Press, Lawrence, U312–U339.

128Mulder, E.W.A., 1999. Transatlantic latest Cretaceous mosasaurs (Reptilia, Lacertilia) from the Maastrichtian type area and New Jersey. Geologie en Mijnbouw, 78, 281–300. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1003838929257

129Neumann, C. & Hampe, O., 2018. Eggs for breakfast? Analysis of a probable mosasaur biting trace on the Cretaceous echinoid Echinocorys ovata Leske, 1778. Fossil Record, 21, 55–66. https://doi.org/10.5194/fr-21-55-2018

130Petsios, E., Farrar, L., Tennakoon, S., Jamal, F., Portell, R.W., Kowalewski, M. & Tyler, C.L., 2023. The Ecology of Biotic Interactions in Echinoids: Modern Insights into Ancient Interactions. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, Elements of Paleontology, 46 p. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108893510

131Polcyn, M.J., Robbins, J.A., Schulp, A.S., Lindgren, J. & Jacobs, L.L., 2025. The evolution of mosasaurid foraging behavior through the lens of stable carbon isotopes. Diversity, 17, 291. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17040291

132Reynders, J.P.H., 1998. Haaien en roggen. In Jagt, J.W.M., Leloux, J. & Dhondt, A.V. (eds), Limburgnummer 9B: Fossielen van de St. Pietersberg. Grondboor & Hamer, 52, 140–141.

133Schulp, A.S., 2005. Feeding the mechanical mosasaur: what did Carinodens eat? In Schulp, A.S. & Jagt, J.W.M. (eds), Proceedings of the First Mosasaur Meeting. Netherlands Journal of Geosciences – Geologie en Mijnbouw, 84/3, 345–357. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0016774600021132

134Serafini, G., Miedema, F., Schweigert, G. & Maxwell, E.E., 2025. Temnodontosaurus bromalites from the Lower Jurassic of Germany: hunting, digestive taphonomy and prey preferences in a macropredatory ichthyosaur. Papers in Palaeontology, 11/3, e70018. https://doi.org/10.1002/spp2.70018

135Street, H.P. & Caldwell, M.W., 2017. Rediagnosis and redescription of Mosasaurus hoffmannii (Squamata: Mosasauridae) and an assessment of species assigned to the genus Mosasaurus. Geological Magazine, 154/3, 521–557. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0016756816000236

136Tajika, A., Rashkova, A., Landman, N.H. & Klompmaker, A.A., 2025. Lethal injuries on the scaphitid ammonoid Hoploscaphites nicolletii (Morton, 1842) in the Upper Cretaceous Fox Hills Formation, South Dakota, USA. Swiss Journal of Palaeontology, 144, 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13358-024-00341-6

137Taverne, L. & Goolaerts, S., 2015. The dercetid fishes (Teleostei, Aulopiformes) from the Maastrichtian (Late Cretaceous) of Belgium and the Netherlands. Geologica Belgica, 18, 21–30.

138Thies, D., 1985. Bißspuren an Seeigel-Gehäusen der Gattung Echinocorys [sic] Leske, 1788 aus dem Maastrichtium von Hemmoor (NW-Deutschland). Mitteilungen aus dem Geologisch-Paläontologischen Institut der Universität Hamburg, 59, 71–82.

139Ubaghs, C., 1885. Catalogue des collections géologiques, paléontologiques, conchyliologiques & d’archéologie préhistorique du Musée Ubaghs à Maestricht, rue des Blanchisseurs, n° 2384. Imprimerie H. Vaillant-Carmanne, Liége, 32 p.

140van de Geyn, W.A.E., 1937. Les élasmobranches du Crétacé Marin du Limbourg hollandais. Natuurhistorisch Maandblad, 26, 16–21, 28–33, 42–53, 56–60, 66–69.

141van Lochem, H., Vis, G.-J. & Jagt, J.W.M., 2025. Late Cretaceous. In ten Veen, J.H., Vis, G.-J., de Jager, J. & Wong, T.E. (eds), Geology of the Netherlands. 2nd ed. Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam, 253–291. https://doi.org/10.2307/jj.27435714.12

142Vellekoop, J., Kaskes, P., Sinnesael, M., Huygh, J., Déhais, T., Jagt, J.W.M., Speijer, R.P. & Claeys, P., 2022. A new age model and chemostratigraphic framework for the Maastrichtian type area (southeastern Netherlands, northeastern Belgium). Newsletters in Stratigraphy, 55, 479–501. https://doi.org/10.1127/nos/2022/0703

143Wallaard, J.J.W., Fraaije, R.H.B., Diependaal, H.J. & Jagt, J.W.M., 2019. A new species of dercetid (Teleostei, Aulopiformes) from the type Maastrichtian of southern Limburg, the Netherlands. Netherlands Journal of Geosciences, 98, e2. https://doi.org/10.1017/njg.2019.1

144Wallaard, J.J.W., Heere, J., Rijke, M. de & Jagt, J.W.M., 2024. The Dercetidae from the type Maastrichtian – an enigmatic group of bony fish. In Jagt, J.W.M., Jagt-Yazykova, E.A., del Prado-Rebordinos, A. & Teschner, E.M. (eds), The 175th Anniversary of the Maastrichtian – a Celebratory Meeting. Maastricht, September 8-11, 2024, Abstract Volume and Programme, 192–194.

145Woodward, A.S., 1891. Note on a tooth of an extinct alligator (Bottosaurus Belgicus, sp. nov.) from the lower Danian of Ciply, Belgium. Geological Magazine, 8/3, 114–115. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0016756800186236

146Manuscript received 19.06.2025, accepted in revised form 10.10.2025, available online 19.12.2025.