Farmers’ willingness to contribute to tsetse and trypanosomosis control in West Africa: the case of northern Côte d’Ivoire

University of Abidjan-Cocody. Faculty of Management and Economics. Agricultural Economist. 08 BP 1295. Abidjan 08 (Côte d’Ivoire). E-mail: koffi_pokou@yahoo.fr

Consulting Agricultural Economist. 8082 Whispering Wind Lane. 20111 Manassas, VA (USA).

University of Abidjan-Cocody. Faculty of Management and Economics. BP V 43. Abidjan (Côte d’Ivoire).

Received on 4 July 2008; accepted on 8 July 2009

Résumé

Analyse contingente de la contribution des éleveurs à la lutte contre la trypanosomose animale en Afrique de l’Ouest : le cas de la Côte d’Ivoire. Une étude portant sur 224 éleveurs a été mise en place en 1997 dans quatre sites représentatifs de la diversité des systèmes d’élevage de la région nord de la Côte d’Ivoire en vue d’évaluer la velléité des éleveurs à contribuer à la lutte par piégeage contre la trypanosomose. Les résultats de l’analyse contingente montrent que 94 % des éleveurs acceptent le principe de la participation financière, 86 % sont disposés à contribuer en main-d’œuvre et 81 % proposent une contribution multiforme. La moyenne proposée est de 236 FCFA (0,47 USD) par tête de bovin par an et de huit journées de travail par exploitation par mois, avec des variations significatives liées au système de production et à la composition raciale du troupeau. Les résultats de l’analyse économétrique indiquent que la connaissance du vecteur de la trypanosomose, la localisation de l’élevage, l’expérience de l’éleveur en tant que chef de parc et la pratique de la transhumance affectent significativement la velléité des éleveurs à contribuer en main-d’œuvre. Très peu de facteurs ont un effet significatif sur le niveau de participation financière. Une approche par modulation est suggérée pour l’organisation d’un système de contributions en vue de pérenniser les acquis de la lutte et la durabilité des bénéfices.

Abstract

The study was conducted in 1997 on a sample of 224 livestock farmers in four clusters representing the diversity in production systems of northern Côte d’Ivoire, in order to evaluate the willingness of beneficiaries to pay for tsetse control using traps and targets. Results of a contingent valuation survey indicate that 94% of respondents are willing to contribute money, 86% are willing to contribute labor and 81% are willing to contribute in both money and labor. Farmers pledged an average contribution of 236 CFA francs (0.47 USD) per head of cattle per year and eight days per month per farm family. Significant differences were noted in the level of resource contributions according to the production system and breed composition of herds. Estimates from a recursive Tobit model of factors affecting willingness to contribute labor reveal the following as significant factors: knowledge of the tsetse fly and trypanosomosis symptoms, location, years of experience as collective herd manager and the practice of transhumance. There are few factors significantly associated with willingness to contribute money. Thus, organizing a scheme for resources contribution to sustain the benefits of tsetse control should take into account the differences in production systems, farm location and breed composition of herds.

1. Introduction

1African Animal Trypanosomosis (AAT) transmitted by the tsetse fly (Glossina spp.) constrains livestock development in West Africa sub-humid areas with 800-1,200 mm of rainfall. About 70% of bovines (12.5 million cattle) in the 12 countries concerned are exposed to the risk of the disease. In cattle, trypanosomosis causes weight loss, poor growth, low milk yield, reduces work capacity, infertility, abortion and eventually death (Murray et al., 1984).

2In Côte d’Ivoire, nearly 1.2 million cattle are exposed to trypanosomosis. The estimated present value of the costs of combating the disease amounts to 5.4 millions USD annually i.e. 5 USD per cattle at risk (ILRAD, 1993). In 1978 the Tsetse and Trypanosomiasis Control Service (SLTAV) of the Ministry of Agriculture and Animal Resources implemented a long-term tsetse control programme, drawing on external funding and technical assistance (FAO, GTZ) to promote community-based tsetse control and support livestock development in the northern and central regions (Kientz, 1993). The Project evolved through several phases including:

3– tsetse surveys and mapping in the northern savannas;

4– research and development of most suitable bait technologies;

5– pilot tsetse control interventions based on odor attractant devices;

6– extension of the intervention zone to central regions of Côte d’Ivoire.

7Since 1994, the project has focused on community participation in terms of both labor and financial contributions to sustain the benefits of tsetse control and the participation of the private sector in the delivery of veterinary inputs (Krüger et al., 2001).

8From 1996-1999, the SLTAV initiated a series of participatory experiments in tsetse control in the northern savanna areas with varying degrees of success. Pilot experiment areas represented about a third of the total project intervention zone with a cattle population of 790,000 of which 80,000 were draft cattle. The majority of the beneficiaries were Senoufo agropastoralists, who are primarily cotton farmers using animal traction and raising a small herd of cattle. The transhumant production system comprised some 3,000 Fulani herders who raise mainly Zebu cattle and hold nearly 50% of the region’s herd. An economic analysis of the Project undertaken after 12 year operations concluded that the project was technically successful (DSV, 1992; Yao, 1992) and economically viable with an internal rate of returns (IRR) of 23% (Shaw, 1993).

9The objective of this paper is to assess the willingness of farmers to contribute to tsetse/trypanosomosis control in northern Côte d’Ivoire with a view to the implementation of a scheme for voluntary contribution of resources that would ensure sustainability as external funding came to an end in 2001. The specific objectives of the study were to:

10– assess the level of money and/or labor contributions by farmers to tsetse control;

11– assess the importance of key factors determining farmers’ willingness to contribute resources to the scheme;

12– formulate recommendations for planning in view of the fact that the next phase of the project will rely mostly on farmers’ contributions while the private sector would be contracted to supply other animal health care inputs.

2. Background

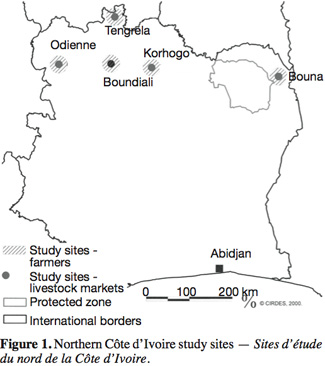

13More than 90% of livestock production in Côte d'Ivoire is carried out in the northern region, especially in the districts of Bouna, Korhogo, Boundiali and Odienné (Figure 1). This region is marked by striking differences in livestock breeds, ownership, production and management systems, including drug use. More than 40% of the cattle in the northern region are raised in transhumant systems, 50% are raised in sedentary systems, and the remaining (less than 10%) are raised only for the provision of animal traction. Baoulé cattle — a trypanotolerant breed — form the dominant breed (52%) in sedentary systems. Zebu which are trypanosusceptible are predominant (64%) in transhumant herds.

14To better represent the differences in livestock production, the northern region was delineated in 1997 into four cluster areas around the towns of Bouna, Korhogo, Boundiali and Odienné. Each cluster had a different profile of cattle breeds (Baoulé, Zebu, N'Dama and their crosses), ethnic groups (Lobi, Senoufo, Malinké), and experiences with tsetse control. Indeed, the sedentary production system is dominant all around Korhogo and cattle breeds mainly include Zebu, and the trypanotolerant breeds - N’Dama and Baoulé. Korhogo has the largest mixture of breeds due to widespread cross-breeding of Zebu and trypanotolerant breeds. Tsetse control started there in 1980. Transhumant production systems predominate in Boundiali with herds mainly composed of Zebu and crossbreeds. Tsetse control also started there in 1980. Livestock owners in Odienné practice a semi-intensive sedentary system with the use of modern inputs. Tsetse control was not started until 1996 and herds are mostly made up of N’Dama. In the Bouna area where ethnic Lobi farmers are numerically important, over 76% of the cattle are raised in sedentary systems. Baoulé cattle represent more than 60% of the cattle population, although there has been an increase in the number of Zebu-Baoulé crosses in recent years. The Bouna area had no tsetse control activities going on at the time of the survey; which can be explained by the fact that this region shares a border with the Comoé National Reserve and the Volta Noire forest, making tsetse control very expensive due to the risk of tsetse flies re-infestation.

3. Research design

3.1. Tsetse control: financing and delivering a local public good

15In recent years concerns about costs, sustainability and environmental safety have helped to stimulate interest in impregnated traps and targets that attract and kill the flies. These devices can be used in combination with pour-on insecticide treatments as a non-polluting and cost effective technique for combating trypanosomosis in cattle. In areas without sleeping sickness, the benefits of tsetse control derive from a reduced risk of animal trypanosomosis. Thus, in a particular area where deployment of traps and targets is effective in reducing the risk of trypanosomosis, these benefits will accrue to only those who live in the concerned zone. Therefore, tsetse control intervention can be regarded as a local public good (Cornes et al., 1996).

16Since all members of the community simultaneously take advantage of the benefits from tsetse control as a public good, the optimal Pareto resources allocation cannot be achieved given efficiency conditions for a competitive market. Following Brookshire et al. (1987), one may consider the case of an individual consumer whose preference is expressed through an utility function with respect to a range of private goods and a public good. Private goods are represented by a vector x = (xk : kEX) while the public good is represented by a scalar z. Its utility function is then defined as U = U (x,a) in which U is an increasing and quasi-concave ordinal utility function. Private goods are subject to transactions on competitive markets at strictly positive prices p = (pk : kEX). There is no market for the public good z but it can be defined by H levels of attributes denoted as a = (ah : hEH). Each attribute is matched with a price qh that depends on the levels of traits contained in the good. These prices reveal an implicit function of the characteristics of the good (Ethridge et al., 1982; Brorsen et al., 1984).

17It is assumed that a rational consumer maximizes his utility function under a budget constraint of the form:

18px + q(a)z ≤ y; for y > 0 (1)

19In equation (1) y stands as the exogenous income. Under this condition, this consumer’s indirect utility function may be represented as follows:

20V(p,q(a),y) = max U(x,a) (2)

21Subject to px+q(a)z ≤ y.

22Supposing a situation where only the supply of public good changes from a0 to a1; then the question is how much money the consumer needs to maintain his initial level of utility. When a0 < a1 the consumer’s willingness to contribute to the provision of the public good measures his ability to pay for the good as indicated in equation (3):

23WTP (p0, q(a1); p0, q(a0), y0) = max y (3)

24Subject to V(p0, q(a1), y) ≥ V(p0, q(a0), y0). WTP is the willingness to pay for the public good. In practice, the provision of a public good is non-optimal since beneficiaries adopt strategies to overestimate their willingness to accept compensations or underestimate their real demand for public goods (Brookshire et al., 1987). Several methods of public goods financing have been proposed among which the Nash and Lindahl model, the principles of majority vote, and the tax scheme (Feldman, 1980; Malinvaud, 1982; Cornes et al., 1996). Empirically and in a non-market context, the contingent analysis has been often used to assess consumers’ willingness to pay for a public good.

3.2. Contingent valuation (CV) technique and data collection

25Contingent valuation (CV) is a common survey method used to measure or estimate the values individuals place on public and quasi-public goods and services (Randall et al., 1983; Cummings et al., 1986; Mitchell et al., 1989; Judez et al., 1998; Carson et al., 2001). With this approach values of unpriced goods and services are elicited from individuals by inquiring about their willingness to pay (WTP) in labour or cash for public and mixed private-public goods or services using CV survey methods (Hanemann, 1994; Swallow et al., 1994). The method has previously been used in industrialized countries to value leisure as is the case in competitive fishing. In developing countries, CV methods have been extended to other fields such as education support or contribution to health care (Tan et al., 1984). The method has also been used to assess people’s willingness to be involved in water supply programs (Whittington et al., 1990; Boadu, 1992; McPhail, 1993), for timber tarification in Zimbabwe (Campbell et al., 1991), for willingness to pay for visiting wildlife in Kenya (Navrud et al., 1994) and in acceptance of a compensation to have access to a forest in Benin (Treiman, 1993). Only recently have the CV methods been used to assess the community participation in the tsetse control. Recent work in this area includes evaluation of/and willingness to pay for tsetse control in Ethiopia (Swallow et al., 1994), in Kenya (Echessah et al., 1997) and in Burkina Faso (Kamuanga et al., 2001).

26The CV survey instrument is a questionnaire that can be administered as a mail-in, telephone, or face-to-face survey. A face-to-face survey is more suitable in a developing country context and is considered the best method of CV data collection because questions that may not be clear to the respondent can be rephrased and/or clarified for the respondent during the interview. Interviews are usually conducted in settings that permit respondents to give considered responses (Hanemann, 1994). Both open-ended and closed questionnaires have been used. Open-ended questions are framed to determine, for example, how much an individual would be willing to pay per month to have a public water standpost near his/her house. Close-ended bidding games ask a series of yes/no questions, towards contributing a specific mentioned amount of money. For example: Would you be willing to pay X CFA francs per month for a public stand post near your house (Whittington et al., 1990)?

27Although both approaches can help to estimate marginal willingness to pay, in practice it is not obvious that the same contingent values will be arrived at (Boyle et al., 1988; O’Doherty, 1996). Seller et al. (1985) and Brown et al. (1996) argue that the closed-ended questionnaire is more reliable when people are more familiar with market situations; they make less effort when prices are so stated, and show their willingness to pay or not to pay for a public good. On the other hand, the open-ended questionnaire bears the risk of under-estimating the contribution while giving room for the free-rider phenomenon from the respondent in the hope that the other individuals will pay more for the good or service (Brown et al., 1996). In any case, efforts are made to reduce the risk of free-riding (Kealy et al., 1993; Brown et al., 1996; Ethier et al., 2000). Practical considerations and the need to keep logistical costs to a minimum favored our use of open-ended questionnaires in the northern Côte d’Ivoire study of farmers’ willingness to contribute to tsetse control.

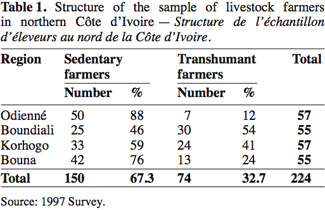

28A sample of 224 livestock-owing farmers (Table 1) was selected in a 60 km radius around each of the 4 clusters’ center in northern Côte d’Ivoire. Stratification of farm production units was elaborated based on the prevailing production system divide i.e. sedentary or transhumant. The sample frame in each cluster area was updated using the list provided by SODEPRA — then a parastatal regional agency for livestock development. Between 50 to 60 livestock keepers were randomly selected from each cluster. Each selected farm was visited at least four times during the year 1997 in order to complete the CV surveys. Respondents were previously made aware of the public good nature of tsetse control through a series of focus group meetings which included raising awareness on the tasks of deploying traps and targets, and the benefits they would reap from effective control. During the surveys, respondents were asked open-ended questions about the maximum number of days per month and/or amount of money per animal per year they would be willing to contribute to the tsetse program.

4. Working hypotheses

29We examined hypotheses about factors affecting livestock owners’ willingness to contribute labor and money to tsetse control on the basis of economic theory and in the light of findings from group discussions, and results obtained elsewhere in similar studies of the determinants of resources contribution to tsetse control (Swallow et al., 1994; Echessah et al., 1997; Kamuanga et al., 2001). The following major factors were examined on the assumption of their effects on payment in labor, money or both modes of contribution:

30– age of the household head: older household heads would be more willing to contribute money to tsetse control rather than labor; traditionally high labor demanding tasks are assigned to younger members of the community;

31– years of experience as herd manager: cattle owners with management responsibilities for the household and/or community herds have relatively less time to devote to field chores; they are more likely to contribute money to tsetse control as compared with those with much less responsibility;

32– ethnicity: owners and herd managers of the Fula ethnic group who migrated into the region, are more likely to contribute to tsetse control in the form of money relative to labor than indigenous livestock farmers would;

33– disposable income: households with higher disposable income from a variety of sources (sale of cattle, milk sales and secondary activities), have larger cash balances; they would be willing to contribute money rather than labor to tsetse control;

34– household size: larger households would have greater demand on available money and hence would be less willing to contribute money and more willing to contribute labor to the tsetse campaign;

35– herd size and composition: households with larger herds (i.e. having a potential for more cash earnings from off-taking of cattle) or those with more trypanotolerant cattle in herds (i.e. spending less on trypanocidal drugs) are likely to hold positive cash balances. Consequently, they would be more willing to contribute in money to tsetse control than households without these characteristics would.

36– education and knowledge of trypanosomosis: household members with formal education and/or knowledge of the disease symptoms are capable of identifying trypanosomosis as major cause of cattle mortality; thus have a favorable pre-disposition for higher levels of resources contribution to tsetse control in either form;

37– practice of sedentary vs transhumant system: this attribute characterizes livestock farmers in northern Côte d’Ivoire in regard to the level of trypanosomosis risk. The practice of transhumance exposes livestock and cattle in particular, to higher risk of contracting the disease. Transhumant herders are likely to spend more on preventive drugs than sedentary farmers. Thus transhumant livestock farmers would be willing to contribute less labor and money to tsetse control.

38– area location: Odienné, Boundiali and Korhogo districts are associated with past tsetse control experience, whereas Bouna had no tsetse control. Willingness to contribute resources is expected to be lower in Bouna for on-going control program.

5. Empirical models

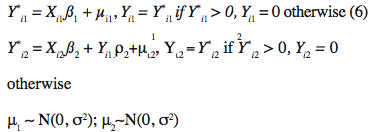

39Forty two of the 224 respondents in the sample made no pledges to contribute resources to tsetse control, either in the form of labor or money. In this situation using the Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression method to estimate the factors affecting willingness to pay (dependent variable) would give rise to biased estimators, given the censured nature of the data (Gaspart et al., 1998; Greene, 2003; Kennedy, 2003). Many approaches have been used to contour such difficulties. Echessah et al. (1997) for example, used the Two-Step estimation procedure suggested by Heckman (1976) to identify key factors explaining the willingness of farmers to contribute resources to a tsetse control program in the Busia District of Kenya. However, while consistent the Two-Step procedure leads to inefficient estimators compared to maximum likelihood estimation (ML) method (Kennedy, 2003). It is nevertheless used in the case of censored but not truncated data when it appears that the cost of computing ML estimators is too high. Similarly, Swallow et al. (1994) used the Three-Stage Least Squares (3SLS) method to estimate the significance of factors affecting farmers’ willingness to participate in tsetse control program in the Gibey Valley of Ethiopia. In our study, the censured nature of the data on hands (labor and money contributions) suggested the use of a Tobit model which yields consistent and asymptotically normal maximum likelihood estimators of parameters (Greene, 2003; Kennedy, 2003). The underlying latent regression used in the Tobit model is presented in the following equation:

40Yi* = Xi ß + µi, i = 1, 2,..., n (4)

41where Yi* denotes a latent response variable, Xi represents an observed 1 x k vector of explanatory variables and µi the error term which is independently and identically distributed (normal distribution curve with zero means and variance 2). For the group of households that did not pledge either labor or money and actually did not contribute any, Yi* cannot be measured and is set equal to 0. Hence, the observed dependent variable (Yi) is given by:

42Yi = Yi* iƒ Yi* > 0 (5)

43Yi = 0 iƒ Yi* ≤ 0

44According to the questionnaire format, the respondent who agrees to contribute to tsetse control was first asked to pledge his level of labor contribution, then prompted to state the level of his money contribution. As suggested by Whittington et al. (1990), the question was posed only after the respondent was provided with a clear explanation of the advantages associated with effectiveness of tsetse control. This approach favored the use of a recursive Tobit model as suggested by Moore et al. (1994) and Hayes et al. (1997) to estimate the parameters in tsetse control, keeping in mind that the farmer’s decision to contribute money is partially determined by his labor contribution as indicated by the order in which the two questions were posed, following the format of the questionnaire. The recursive Tobit model is presented as follows:

45where Y*i1 is the willingness to contribute labor by farmer i while Y*i2 is the willingness of farmer i to contribute money. Yi1 stands for the actual amount of labor (in days per month) that farmer i stated he/she will contribute; Yi2 is likewise the amount of money (in CFA francs per head per year) that farmer i stated he/she will contribute. Y*i1 and Y*i2 are two latent variables with observed values being estimated as follows:

46Yi1 = Y*i1 I(Y*i1 > 0) et Yi2 = Y*i2I(Y*i2 > 0)

47I(.) is an indicator function.

48Xi1 is the vector of variables explaining labor contribution and Xi2 the vectors explaining money contribution. The vectors of parameters to be estimated are shown as follows:

49ßj (j=1,2) and 2.

6. Results

6.1 Levels of resources contribution

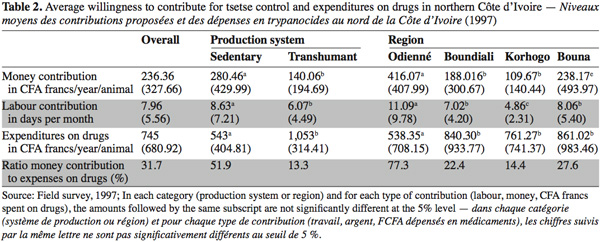

50Nearly 94% of the respondents volunteered to contribute money while 86% volunteered to contribute labor. The proportion of farmers pledging both types of contribution was 81.2%. The average amount of resources that farmers pledged to contribute for tsetse control are shown in table 2. For the study zone as a whole the average money contribution amounts to 236.36 CFA francs per year per animal (0.47 USD), and 7.96 working days per month per household. Willingness to contribute money represents only 32% of what the farmers spend on trypanocidal drugs. Controlling for production system, the sedentary livestock farmer is willing to pay twice as much (280 CFA francs per year per animal vs 140 CFA francs) and contribute 30% more labor (8.63 days per month vs 6.07 days) to tsetse control than the transhumant farmer would.

51Pair wise comparisons between regions reveal striking significant differences (P < 0.05) between Odienné and Bouna, while there is no significant difference in money contribution between Boundiali and Korhogo. There are also large significant differences in contributions between Odienné and Boundiali. Odienné farmers are willing to pay 416 CFA francs per year per animal and contribute 11 days per month to tsetse control compared to 238 CFA francs and 8 days for Bouna, and 188 CFA francs and 7 days for Boundiali.

52Expenditures on drugs are significantly lower in Odienné (538 CFA francs per year per animal) than in the rest of the three regions. Odienné is the only region where the proposed money contribution also represents nearly 80% of what farmers actually spend on drugs, despite the fact that the proportion of trypanotolerant N’Dama cattle in herds is higher than in Boundiali and Korhogo. The level of pledged financial contribution in Korhogo (110 CFA francs per year per animal) is the lowest of any region, but is more in line with our expectations. In fact it is known that transhumant farmers have been extensively developing their activities in this region (41.4% of all livestock farmers) with a steady trend toward settlement. Only those settlers who are not landowners seem reluctant to take part in any significant way in efforts to combat trypanosomosis in the region. Pledged contributions in money by transhumant herders represent only 13% of what they normally spend annually on drugs.

53Money contribution in Bouna is higher than in Korhogo and Boundiali, but remains lower than in Odienné where farmers’ contribution amounts to 28% of their annual expenses for drugs. It appears that farmers who spend more on trypanocides (transhumant farmers and farmers in Boundiali and Korhogo) are also those who pledge the lowest money contribution. This implies that livestock farmers in northern Côte d’Ivoire substitute money contributions for financing traps and targets (public local good) for cash expenditures on therapeutic and prophylactic treatments (private good).

54Regional disparities may be summarized as follows: Korhogo and Boundiali are not significantly different at the 5% level in terms of money contributions to tsetse control. Farmers in Odienné are noticeably willing to spend more cash than farmers in any other region. In terms of labor contribution, Bouna and Boundiali are not significantly different. The level of both types of contributions is significantly different between Odienné and the rest of the regions.

6.2. Key explanatory factors of contribution to tsetse control

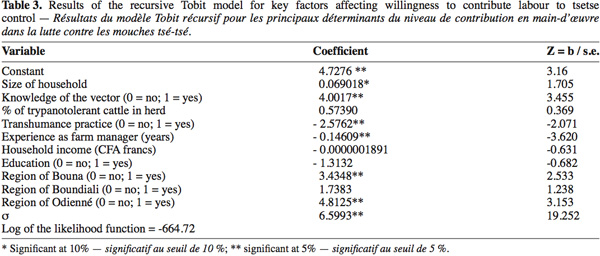

55Results of the Tobit model regarding willingness to contribute (WTC) labor (dependant variable) and money (dependant variable) were generated with LIMDEP, 7.0 version (Greene, 1995). The estimated model indicates a large, negative logarithm of the likelihood function, with a low basic value. Several of the hypothesized factors determining WTC labor and the magnitude of such contributions are significant at either 5% or 10% levels as shown in table 3.

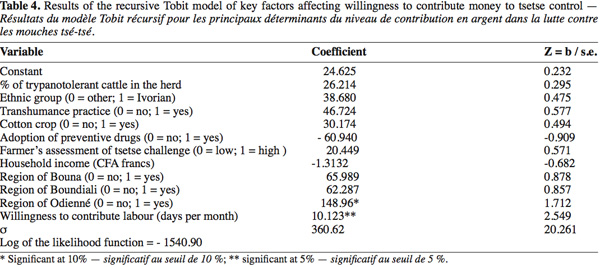

56Years of experience as herd manager and the practice of transhumance have a negative impact on the level of labor contribution. Indeed older farmers being the most experienced in herd management do not clearly perceive the benefits of tsetse control as a public good and logically tend to invest less labor in trapping operations. The majority of transhumant farmers do not own land and thus show little interest to participate in bush clearing for tsetse control, or to contribute to community works. Knowledge of trypanosomosis (ability to identify the tsetse fly and information on how the disease can be transmitted) is a significant factor in the decision to contribute labor to tsetse control. Larger households have the ability to supply manpower for tsetse control, although WTC labor is only significant at 10% level. However, neither the size of the herd – initially taken into account in previous runs of the model – nor the proportion of trypanotolerant animals in herds had any significant association with WTC labor. This result confirms previous findings in similar studies of willingness to contribute labor to tsetse control in East Africa (Swallow et al., 1994; Echessah et al., 1997). Factors determining money contribution are shown in table 4. Willingness to contribute labor – introduced as explanatory variable – and the dummy variable for location in Odienné are the only significant determinants of WTC money in tsetse control.

7. Discussion and conclusions

57The results indicate that more than 80% of the farmers are willing to contribute both money and labor to tsetse and trypanosomosis control. This is in line with previous findings in East and West Africa (Gouteux et al., 1990; Swallow et al., 1994; Echessah et al., 1997; Mugalla, 2000; Kamuanga et al., 2001) which concluded that where there is evidence of animal trypanosomosis and where people are previously aware or made to be aware of the problem, the majority will indicate general interest in solution. The implication for northern Côte d’Ivoire is that part of the costs of tsetse control could be transferred to beneficiaries, a key condition to ensure the sustainability of benefits. Proposed levels of contribution remain low relative to the actual costs of setting the traps and targets, their maintenance and replacement. In spite of their willingness to contribute money, most farmers lack reliable information about the costs, benefits, efficiency and sustainability of the tsetse control as a local public good. This is the reason why farmers exercise caution and are reluctant to pledge substantial amounts of money in contribution in the belief that this could be used against them as the basis for taxation of the benefits they would eventually derive from effective control.

58Due to the questionnaire format – the farmer asked to state his willingness to contribute labor first before contributing money – we used a recursive Tobit model to identify and assess the level of key factors determining willingness to contribute resources. The analysis points to the size of households and knowledge of the trypanosomosis symptoms and vector as factors that positively affect labor contribution. Improved extension services are thus needed in providing training programs intended for farmers in the regions under tsetse control. Because of the time-consuming responsibilities in the management of collective herds, herd managers commonly referred to as “chefs de parc” are less willing to contribute labor for tsetse control. There is an urgent need to sensitize young farm managers and the village youth groups to engage in such labor demanding tasks of traps installation, up-keep and replacement.

59It is interesting to note that location in Odienné and labor contribution were found to be statistically significant determinants of WTC money, which confirms the results of similar studies in East Africa (Swallow et al., 1994; Echessah et al., 1997). In northern Côte d’Ivoire this result could be linked to farmers’ strategic behavior. In fact farmers at large have for long operated under a subsidized scheme of free veterinary drugs, low cost of feeds and access to infrastructures such as dams and cattle contention structures over the 1972-1992 period. In the expectation of still more subsidized services, willingness to contribute money for tsetse control may have decreased.

60Where communities live and depend on cattle for their livelihoods, as it is the case with pastoralists who migrated into northern Côte d’Ivoire, it is the benefit-cost assessment of alternative strategies that influences their decision to contribute resources to tsetse control. It would be most appropriate to organize a scheme for fund collection in a lump sum for transhumant livestock farmers, the amount of which should not exceed 200 CFA francs per animal per year. Indeed requests for money contribution should remain below the total cost of drugs considered as the most important factor for all farmers. Kientz (1993) had concluded that farmers’ cash contribution would be more realistic as long as the cost of tsetse control does not exceed what they normally pay for drug therapy.

61The discrepancy in proposed levels of contribution between sedentary and transhumant farmers on the one hand, and between geographic zones, on the other hand, suggests that a modulated fund collection scheme by production system and location may be appropriate to sustainably secure a common fund that would help finance traps and targets. Indeed livestock farmers in Odienné with mostly trypanotolerant cattle in herds tend to adopt new technologies and are willing to invest in impregnated traps and screens to protect the surrounding pastures where their cattle graze. On the other hand, we can make the point that the low level of pledged contributions in Bouna can be partly attributed to the fact that farmers are traditionally less inclined to adopt technological innovations, although its sedentary system in an area without tsetse control would have implied levels of contributions higher than Boundiali and Korhogo.

62Contrary to difficulties linked with assessment of the value of local public goods, the costs of tsetse control can be estimated prior to its implementation. Indeed, if each of the livestock farmer in northern Côte d’Ivoire were to pay 240 CFA francs per animal per year (0.65 USD), the amount collected would be insufficient to cover the investment. One can argue that Contingent Valuation estimates of willingness to pay cannot be used in benefit-cost analysis. Nevertheless they can serve as a source of significant informational value given that much of decision making on such investments in rural West Africa is often made without any reference to such evaluation.

63These estimates could be helpful particularly at this point of restocking and rebuilding Côte d’Ivoire’s most promising region for livestock development following seven years of civil upheaval. Setting in the initial level of subsidy based on CV evaluation will most likely provide a basis for gradually increasing the quantity and quality of improvement in animal health services and herd productivity parameters.

Bibliographie

Boadu O.F., 1992. Contingent valuation for household water in rural Ghana. J. Agric. Econ., 43(3), 458-465.

Boyle K.J. & Bishop R.C., 1988. Welfare measurement using contingent valuation: a comparison of techniques. Am. J. Agric. Econ., 70(6), 20-28.

Brookshire S.D. & Coursey L.D., 1987. Measuring the value of a public good: an empirical comparison of elicitation procedures. Am. Econ. Rev., 77(4), 554-566.

Brorsen B.W., Grant W.R. & Rister E.M., 1984. A hedonic price model for rough rice bid/acceptance markets. Am. J. Agric. Econ., 66(2), 156-163.

Brown T.C., Champ P.A., Bishop R.C. & McCollum D.W., 1996. Which response format reveals the truth about donations to a public good? Land Econ., 72(2), 152-166.

Campbell B.M., Vermeulen S.J. & Lynam T., 1991. Value of trees in small-scale farming sector of Zimbabwe. Ottawa: International Development Research Centre (IDRC).

Carson T.R., Flores E.N. & Meade F.N., 2001. Contingent valuation: controversies and evidence. Environ. Resour. Econ., 19, 173-210.

Cornes R. & Sandler T., 1996. The theory of externalities, public goods, and club goods. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Cummings R.G., Brookshire D.S. & Schulze W.D., 1986. Valuing environmental goods: a state of the art assessment of the contingent valuation method. Totowa, N.J., USA: Rowman & Allanheld.

DSV (Direction des Services Vétérinaires), 1992. Organisation du service de lutte contre la trypanosomiase animale et les vecteurs au-delà de 1993. Projet de lutte anti tsé-tsé, Korhogo. Abidjan : Ministère de l’Agriculture et des Ressources Animales.

Echessah N.P., Swallow B.M., Kamara D.W. & Curry J.J., 1997. Willingness to contribute labor and money to tsetse control: application of contingent valuation in Busia District, Kenya. World Dev., 25(2), 239-253.

Ethier R.G., Poe G.L., Schultz W.D. & Clark J., 2000. A comparison of hypothetical phone mail contingent valuation responses for Green-pricing electricity programs. Land Econ., 76, 54-67.

Ethridge D.E. & Davis B., 1982. Hedonic price estimation for commodities: an application to cotton. West. J. Agric. Econ., 7, 293-300.

Feldman M.A., 1980. Welfare economics and social choice theory. Boston, USA; The Hague, The Netherlands; London, UK: Martinus Nijhoff Publishing.

Gaspart F., Jabbar M., Méllard C. & Platteau J.P., 1998. Participation in the construction of local public goods with indivisibilities: an application to watershed development in Ethiopia. J. Afr. Econ., 7(2), 157-184.

Gouteux J.P. & Sinda D., 1990. Community participation in the control of tsetse flies: large scale trials using the pyramid trap in the Congo. Trop. Med. Parasitol., 41, 49-55.

Greene W.H., 1995. LIMDEP. Reference guide. Version 7.0. Bellport, NY, USA: Econometric Software Inc.

Greene W.H., 2003. Econometric analysis. 5th ed. Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA: Prentice Hall.

Hanemann W.M., 1994. Valuing the environment through contingent valuation. J. Econ. Perspect., 8(4), 19-43.

Hayes J., Roth M. & Zepeda L., 1997. Tenure security, investment and productivity in Gambian agriculture: a generalized probit analysis. Am. J. Agric. Econ., 79, 369-382.

Heckman J.J., 1976. The common structure of statistical models of truncation, sample selection and limited dependent variables and simple estimator for such models. Ann. Econ. Soc. Meas., 5, 475-492.

ILRAD (International Laboratory for Research on Animal Diseases), 1993. Annual scientific report. Nairobi : ILRAD.

Judez L. et al., 1998. Évaluation contingente de l’usage récréatif d’une réserve naturelle humide. Cah. Écon. Sociol. Rurales, 48.

Kamuanga M., Swallow B.M., Sigue H. & Bauer B., 2001. Evaluating contingent and actual contributions to a local public good: Tsetse control in the Yale agro-pastoral zone, Burkina Faso. Ecol. Econ., 39, 115-130.

Kealy M.J. & Turner R.W., 1993. A test of the equality of closed-ended and open-ended contingent valuations. Am. J. Agric. Econ., 75, 321-331.

Kennedy P., 2003. A guide to econometrics. 5th ed. Malden, MA, USA: Blackwell Publishers.

Kientz A., 1993. La lutte contre le vecteur de la trypanosomiase animale au service du développement agro-pastoral et possibilités de prise en charge de la lutte par les bénéficiaires. Abidjan : Ministère de l’Agriculture et des Ressources Animales ; Eschborn, Allemagne : GTZ.

Krüger W. et al., 2001. La prise en charge de la lutte anti-tsétsé par les bénéficiaires : l’expérience de la Côte d’Ivoire. In : Proceedings of the 25th Meeting of the International Scientific Council for Trypanosomiasis Research and Control (ISCTRC), 1999. Nairobi: Organization of African Unity/Scientific and Technical Research Commission (OAU/STRC), publication n°120, 393-397.

Malinvaud E., 1982. Leçons de théorie microéconomique. 4e éd. Paris : Dunod.

McPhail A.A., 1993. The "five percent rule" for improved water service: can households afford more? World Dev., 21(6), 963-973.

Mitchell R.C. & Carson R.T., 1989. Using surveys to value public goods: the contingent valuation method. Washington, DC, USA: Resources for the future.

Moore R.M., Gollehon N.R. & Carey M., 1994. Multicrop production decisions in western irrigated agriculture: the role of water price. Am. J. Agric. Econ., 76, 859-874.

Mugalla CI., 2000. Household decision making under different levels of trypanosomiasis risk: an investigation of factors affecting disease control, labour participation, and income decisions in rural household of the Gambia. PhD thesis: Pennsylvania State University, Department of Agricultural Economics and Rural Sociology, Pittsburg (USA).

Murray M. & Gray A.R., 1984. The current situation on animal trypanosomosis in Africa. Prev. Vet. Med., 2, 23-30.

Navrud S. & Mungatana E.D., 1994. Environmental valuation in developing countries: the recreational value of wildlife viewing. Ecol. Econ., 11(2), 135-151.

O’Doherty R., 1996. Using contingent valuation to enhance public participation in local planning. Reg. Stud., 30(7), 667-678.

Randall A., Hoehn J.P. & Brookshire D.S., 1983. Contingent valuation surveys for valuing environmental assets. Nat. Resour. J., 23, 635-648.

Seller C.J., Stoll J.R. & Chavas J.P., 1985. Validation of empirical measures of welfare change: a comparison of nonmarket techniques. Land Econ., 61, 156-175.

Shaw A.P.M., 1993. An economic analysis of the Ivoiro-German tsetse control project in Côte d'Ivoire 1978 to 1992. Berlin, Germany : Freie Universität Berlin; Eschborn, Germany: GTZ.

Swallow B.M. & Woudyalew M., 1994. Evaluating willingness to contribute to a local public good: application of contingent valuation to tsetse control in Ethiopia. Ecol. Econ., 11, 153-161.

Tan J.P., Lee K.H. & Mingat A., 1984. User charges for education: the ability and willingness to pay in Malawi. World Bank Staff Working Papers n°661. Washington, DC, USA: The World Bank.

Treiman T.B., 1993. Conflicts over resource valuation and use in the Pendjari, Benin: the chief has no share. Ph.D. thesis: Department of Agricultural Economics, University of Wisconsin, Madison (USA).

Whittington D., Briscoe J., Mu X. & Baron W., 1990. Estimating the willingness to pay for water services in developing countries: a case study of the use of contingent valuation surveys in southern Haiti. Econ. Dev. Cult. Change, 22(2), 293-311.

Yao Y., 1992. Stratégies de lutte contre la trypanosomiase animale et les mouches tsé-tsé en Côte d'Ivoire. Service de lutte contre la trypanosomiase animale et les vecteurs. Zone Centre, Bouaké. Abidjan : Ministère de l’Agriculture et des Ressources Animales.